Abstract

Physiological and pathological processes that increase or decrease the central nervous system's need for nutrients and oxygen via changes in local blood supply act primarily at the level of the neurovascular unit (NVU). The NVU consists of endothelial cells, associated blood–brain barrier tight junctions, basal lamina, pericytes, and parenchymal cells, including astrocytes, neurons, and interneurons. Knowledge of the NVU is essential for interpretation of central nervous system physiology and pathology as revealed by conventional and advanced imaging techniques. This article reviews current strategies for interrogating the NVU, focusing on vascular permeability, blood volume, and functional imaging, as assessed by ferumoxytol an iron oxide nanoparticle.

Keywords: Blood-brain barrier, Imaging, Neurovascular unit

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2-PM

2-photon microscopy

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CBV

cerebral blood volume

- CNS

central nervous system

- CVR

cerebrovascular reactivity

- DCE

dynamic contrast enhancement

- DSC

dynamic susceptibility contrast

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GBCA

gadolinium-based contrast agents

- NVU

neurovascular unit

- PET

positron emission tomographic

- rCBV

relative CBV

- rs-fMRI

resting state functional MRI

- SS-CBV

steady-state CBV

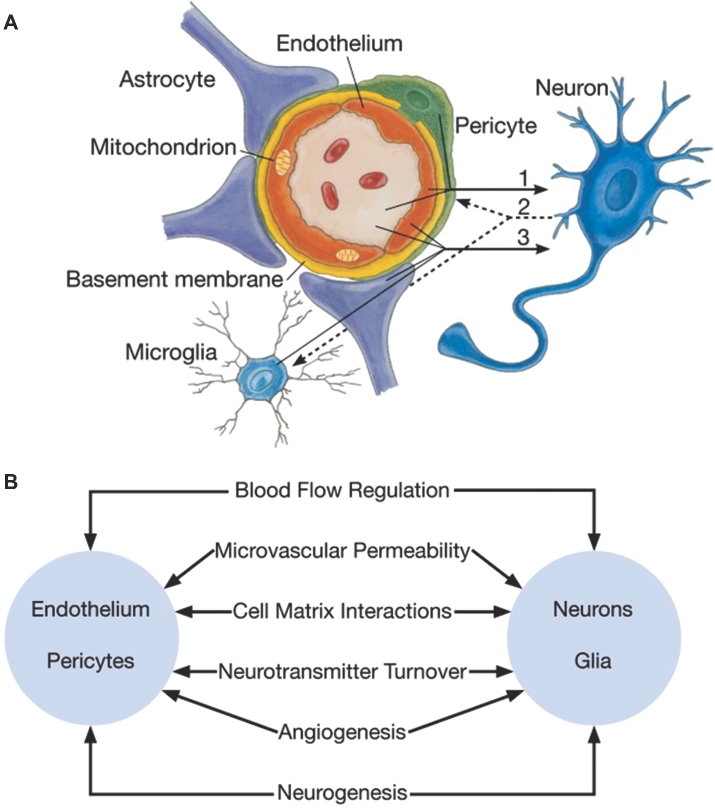

The neurovascular unit (NVU) is defined as a complex functional and anatomical structure composed of endothelial cells and their blood–brain barrier (BBB) forming tight junctions, a basal lamina covered with pericytes and smooth muscular and neural cells, including astrocytes, neurons, and interneurons, and an extracellular matrix (Figure 1).1-3 These cells and extracellular components are intimately and reciprocally linked to form a complex multicellular entity that regulates regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) and nutrient delivery.4 The NVU is vital for autoregulation of CBF oxygen and nutrient delivery.5,6

FIGURE 1.

A, Schematic of the neurovascular unit. In neuronal disorders that have a primary vascular origin, circulating neurotoxins cross the blood–brain barrier to reach their targets, or proinflammatory signals from vascular cells or reduced capillary blood flow disrupt normal synaptic transmission and trigger neuronal injury (arrow 1). Microglia sense signals from neurons (arrow 2). Activated endothelium, microglia, and astrocytes signal back to neurons, which in most cases aggravate the injury (arrow 3). In primary neuronal disorders, signals from neurons are sent to vascular cells and microglia (arrow 2), which activate the vasculoglial unit and contribute to progression of injury (arrow 3). B, Coordinated regulation of normal neurovascular functions depends on vascular cells (endothelium and pericytes), neurons, and astrocytes. Reprinted Neuron 57(2), Zlokovic et al,3 The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders, pp 178–201, 2008, with permission from Elsevier.

Central nervous system (CNS) capillaries are continuous, nonfenestrated vessels adapted to local demands to deliver nutrients while remaining impervious to harmful compounds.7,8 Endothelial cells and support structures are thin compared to those found in other organs. Brain endothelial tight junctions play an essential role in the integrity of the BBB, securely connecting the endothelial cells together. A combination of cell membrane transporters and endocytosis enables movement of molecules across endothelial cells while maintaining solute gradients. These mechanisms are energy intensive and play important roles in meeting the metabolic demands of endothelial cells.9

Understanding the function and structure of the NVU is fundamental to all aspects of normal CNS vascular physiology and pathogenesis of many diseases.10,11 To decipher the complexity of the NVU, different imaging techniques have been employed, ranging from basic science laboratory tools such as 2-photon fluorescence microscopy, laser speckle, and intrinsic optical imaging, to translational and clinical imaging modalities such as positron emission tomographic (PET) and MRI. The choice of imaging depends on the spatial and temporal resolution, required to answer the questions being addressed. This review will focus on the use of ferumoxytol, an iron oxide nanoparticle, as an MRI contrast agent, useful for vascular imaging early after injection and as a noninvasive biomarker of inflammatory response in later time points.

Major challenges of imaging the NVU include visualizing the physical relationships between and defining molecular interactions among the individual NVU components, and integrating these findings into understanding the physiological and pathological function of the NVU. Here we summarize some of the research on advances in imaging the NVU that emerged from the Twenty-first Annual Blood-Brain Barrier Consortium Meeting, March 19-21, 2015, in Stevenson, Washington.

EXPERIMENTAL, BASIC, AND TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE

Significant strides have been made toward understanding how the NVU accomplishes rapid and regional increases in blood flow and nutrient influx following neuronal activation. Early in Vitro models studied 1 or 2 NVU components such as isolated brain vascular endothelial cells or intact brain capillaries but failed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complete functional unit.12 The in Vitro brain slice preparation constitutes a more complete model to study cell-to-cell communications, as it possesses all of the constituents of the NVU with the addition of local circuits that allow for precise stimulation of discrete neuronal and/or astrocytic targets while simultaneously monitoring the activity of vascular cells.5 However, because this is an in Vitro technique, dynamic NVU functions may be difficult or impossible to reproduce.

In Vivo techniques provide dynamic observation of NVU function but have their own challenges. In Vivo 2-photon microscopy (2PM) permits visualization of hundreds of micrometers below the cerebral cortex surface. 2PM can dynamically scan cortex and tissues and allows a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological events to be captured at a cellular resolution from virtually the entire cortical vascular bed. 2PM has the potential to provide important new insights into NVU physiology through its capability to capture in Vivo dynamics longitudinally at subcellular resolution.13

Dynamic processes such as vascular permeability can be quantified by monitoring extravasation of an intravascular tracer. Recently, this tool has become instrumental in defining basic aspects of the BBB and the NVU microenvironment, providing important groundwork for downstream translational and clinical imaging.14

Disease-specific molecular remodeling of the NVU may provide useful information on differential diagnosis, disease severity and progression, and response to treatment.11 Detection of molecular NVU changes by noninvasive imaging necessitates development of targeting molecules that are specific markers of NVU pathology.15 During the last decade, peptides and antibody fragments have expanded the field of molecular imaging agents for indications including brain tumors, neurodegenerative diseases, and neuroinflammation.16

CLINICAL SCIENCE

Recent tools that allow the study of NVU function in clinical practice include new contrast media, radiotracers, and techniques for postprocessing. Evaluating the NVU in patients via minimally invasive approaches is essential to understanding the pathophysiology and potential treatments of brain disease in Situ. Nearly every clinical imaging modality has been employed to evaluate blood–brain permeability through the brain microvasculature.

Permeability and Perfusion

MRI techniques that utilize gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA) are the most commonly employed to assess vascular permeability and NVU structure and function in both animal and human models of disease. Investigators have relied on dynamic contrast enhancement (DCE) in which extravasation of a contrast agent into the brain is recorded over several minutes. DCE-MRI is used to quantify cerebral vascular abnormalities in animal models of cerebral focal ischemia,17,18 methamphetamine use,19 and tumors.20 DCE-MRI is also used in humans,21 and the effects of focal ischemia,22,23 multiple sclerosis,24,25 and cerebral cavernous malformations26 on BBB transfer rate (Ktrans) have been studied. Subtle changes in Ktrans detected in patients with cognitive impairment correlate with vascular injury biomarkers such as matrix metalloproteinases.27 Compartmental modeling of contrast agent extravasation allows the estimation of Vp (blood plasma volume per unit volume of tissue). Along with Ktrans, Vp can be used to map pathologic BBB leakage.

Challenges in translating the BBB transfer rate measurement to clinical use include its relatively long acquisition time, limitations of contrast-based imaging such as nonlinear behavior (saturation effect), limitations of compartmental modeling techniques such as simplification of the biology and the requirement of an arterial input function, and lack of a uniform mathematical approach for modeling the effect of contrast agent leakage on imaging parameters. Nonparametric approaches for analyzing DCE-MRI datasets have been proposed and deserve further investigation.28

As opposed to DCE-MRI, dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) MRI tracks the first pass of a contrast agent through a given tissue. DSC-MRI measures signal change following injection of a paramagnetic contrast agent, typically GBCA, which results in a reduction in signal intensity as it passes through the capillaries. This signal loss from the first passage of the contrast bolus is proportional to contrast agent concentration in each voxel, allowing estimation of CBF, cerebral blood volume (CBV), and mean transit time. DSC-MRI can characterize hemodynamics for determination of tumor grade, predict clinical response and malignant transformation, distinguish between recurrent tumor and radiation necrosis, and differentiate true early progression from pseudoprogression.29,30 Only a small number of high-quality data sets exist, and as there are no standardized, consensus-based methods for performing DSC-MRI, reproducibility remains a substantial hurdle.31

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles such as ferumoxytol (Feraheme) have been used as MRI contrast agents and provide similar or complementary information compared to GBCA-enhanced MRI. Ferumoxytol demonstrates immediate intravascular enhancement with a long half-life (14 h and 11 min) in the blood pool and progressively increasing accumulation (hours to days/weeks postinjection) within macrophages, bone marrow, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes.32

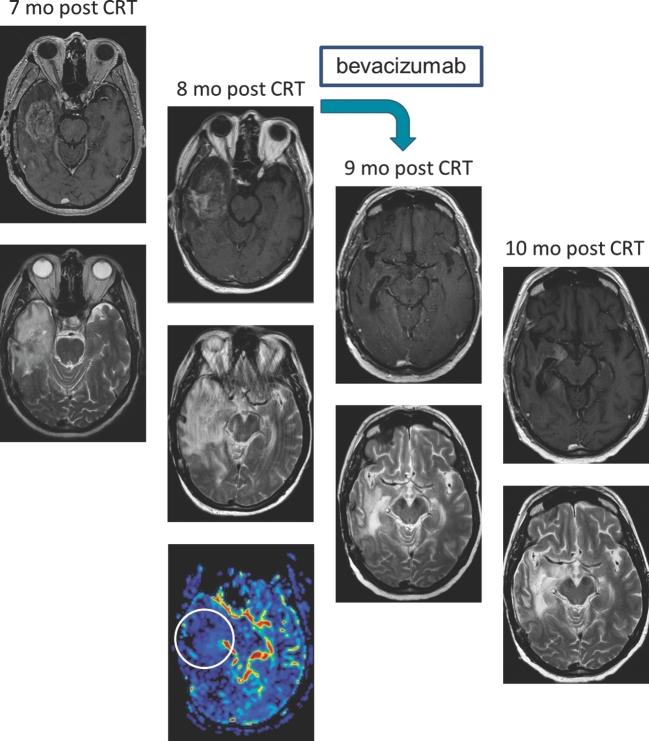

Due to its prolonged intravascular half-life, ferumoxytol permits dynamic vascular and perfusion imaging, which may allow differentiation between true tumor progression and pseudoprogression after treatment. Although the appearance of these 2 processes is similar on standard MRI, they have different tumor NVU profiles. Increased contrast enhancement with low relative CBV (rCBV; < 1.75) on perfusion MRI suggests pseudoprogression (ie, inflammation), whereas high rCBV (>1.75) suggests tumor progression (ie, hypervascularity within the tumor). Ferumoxytol-based perfusion imaging of brain tumors shows greater reproducibility and consistency than GBCA33 without the need for variable preloading doses and specialized postprocessing software such as leakage correction. This could improve standardization across institutions for research and ultimately clinical use by allowing accurate and consistent diagnosis of pseudoprogression and treatment-related injuries as well as pseudoresponse after antiangiogenic therapy.34,35 The issue of prospectively differentiating true progression from pseudoprogression is becoming increasingly problematic in interpreting results from CNS vaccine trials (Figure 2). We believe that rCBV should be a part of patient enrollment criteria in experimental studies, with the goal of decreasing the chance of enrolling patients with pseudoprogression, the proportion of which could be as high as 30% to 40% in glioblastoma.36

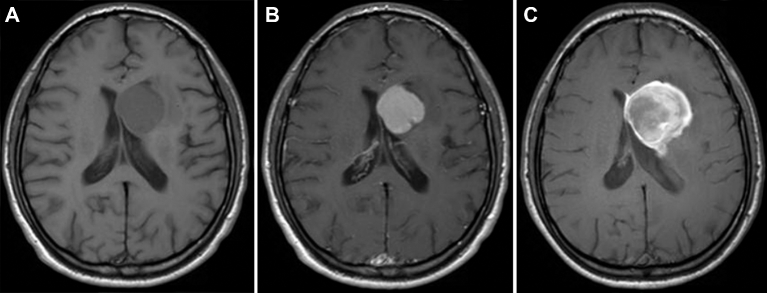

FIGURE 2.

Vaccine response vs tumor progression. The patient received an anti-EGFRv3 vaccine (Celldex) 3 and 4 mo after chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and adjunct temozolomide. Dramatic increased mass effect 7 mo post-CRT and 4 mo after Celldex vaccine. At this point, the patient might be falsely classified as disease progression by updated Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology criteria. Column 1: 7 mo after CRT shows residual enhancing lesion in the right temporal lobe (top: T1 + Gd, bottom: T2). Column 2: 8 mo after CRT shows increased size of the lesion and exuberant vasogenic edema and mass effect on the lateral ventricle and midline shift. Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MRI 8 mo after CRT shows decreased cerebral blood volume in the enhancing area in the right temporal lobe, suggesting pseudoprogression (top: T1 + Gd, middle: T2, bottom: DSC). Column 3: 9 mo after CRT and 4 wk after bevacizumab shows significant improvement in the enhancement, vasogenic edema, and mass effect (top: T1 + Gd, bottom: T2). Column 4: 10 mo after CRT and 8 wk after bevacizumab shows minimal increase of enhancement and mass effect, still significantly better than before bevacizumab (top: T1 + gd, bottom: T2).

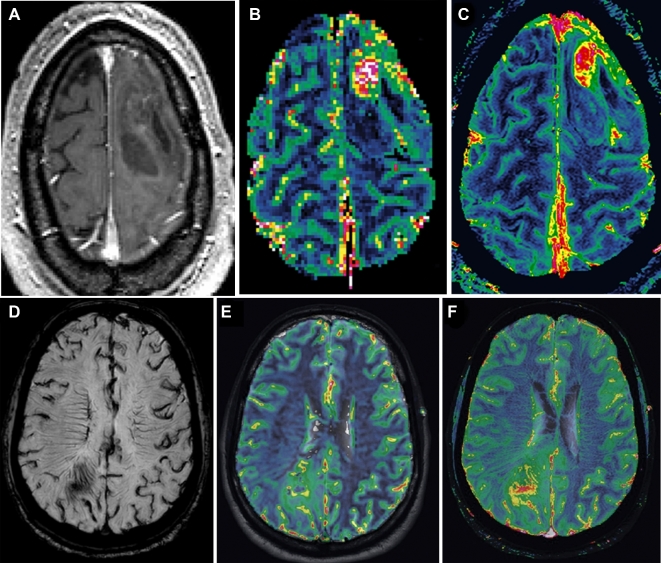

High-resolution, steady-state CBV (SS-CBV) mapping has been tested in brain tumors using ferumoxytol and appears to be superior to dynamic (DSC) perfusion imaging for both tumor targeting and assessment of treatment.37,38 Ferumoxytol has been shown to be useful in biopsy guidance in brain tumors by virtue of identifying small areas of high blood volume, which are suggestive of the most malignant portion of the tumor. In primary gliomas, increased blood volume has been associated with higher-grade tumor (pilocytic astrocytoma as an exception); when total resection is contraindicated and a specific target has to be chosen for biopsy, the area with the highest CBV should be identified29 (Figure 3A-C). Ferumoxytol perfusion MRI with DSC and SS-CBV has the potential to show small areas of increased CBV in the tumor, sometimes in a distinct location from the GBCA enhancement (Figure 3D-F). In patients with suspected CNS lymphoma or other lymphoproliferative disorders that are highly responsive to chemotherapy, diagnostic biopsies are essential, but in many cases the tissue obtained is not diagnostic. Delayed enhancement with ferumoxytol has been shown to increase the sensitivity of brain biopsies in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders due its different mechanism of enhancement compared to GBCA, with increased uptake by local macrophages, abundant in this type of tumor.39 However, this superiority remains to be tested in prospective clinical studies.33,37Table compares the different MRI methods to access perfusion of the NVU.40

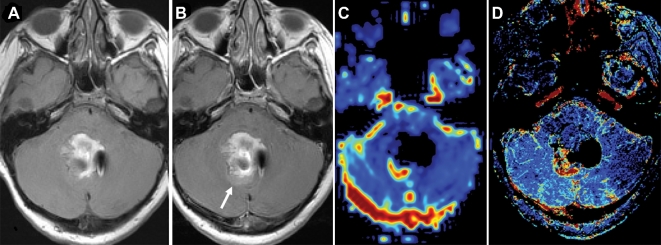

FIGURE 3.

A, High-resolution steady-state MRI of a patient with GBM for surgical targeting. T1-weighted MRI after administration of gadolinium-based contrast agents shows a heterogeneous lesion in the left frontal lobe with faint enhancement. B, Gadolinium-based contrast agent dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) perfusion shows increased relative cerebral blood volume (CBV) in the anterior aspect of the lesion. C, Ferumoxytol-based high-resolution steady-state map shows the focal area of increased relative CBV, easily differentiated from normal cortex and vessels. Comparison of steady-state cerebral blood volume (SS-CBV) and DSC-CBV maps in a patient with a GBM. D, High-resolution SWI minimum intensity projection shows abnormal vascularization in and around the tumor. In corresponding slices, the DSC-CBV E and SS-CBV F maps show increased areas of CBV in these areas, indicating the ideal target for needle biopsy. Reprinted from Kidney International, 92(1), Toth GB, Varallyay CG, Horvath A, Current and potential imaging applications of ferumoxytol for magnetic resonance imaging, pp 47–66, 2017,81 with permission from Elsevier.

TABLE.

Comparison of Different MRI Methods to Access Neurovascular Unit Perfusion

| DCE | DSC | SS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | GBCA ferumoxytol | GBCA ferumoxytol | Ferumoxytol |

| Model parameters | ktrans, vp, ve, IAUC | CBV, CBF, MTT | CBV |

| Spatial resolution | 1 mm in plane | 2 mm in plane | 0.41 mm in plane |

| Slice thickness | 5 mm | 5 mm | 2.2 mm |

| Geometric artifact | Low impact | Prone to problems at the skull base | Prone to problems at the skull base |

| Dynamic | Yes | Yes | No |

| Total acquisition time | 3-5 min | 2 min | 8 min |

DCE = dynamic contrast-enhanced, DSC = dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced, ktrans = transfer constant, vp = fractional volume of the plasma space, ve = fractional volume of the extravascular-extracellular space, IAUC = initial area under the contrast agent concentration-time curve, CBV = cerebral blood volume, CBF = cerebral blood flow, MTT = mean transit time.

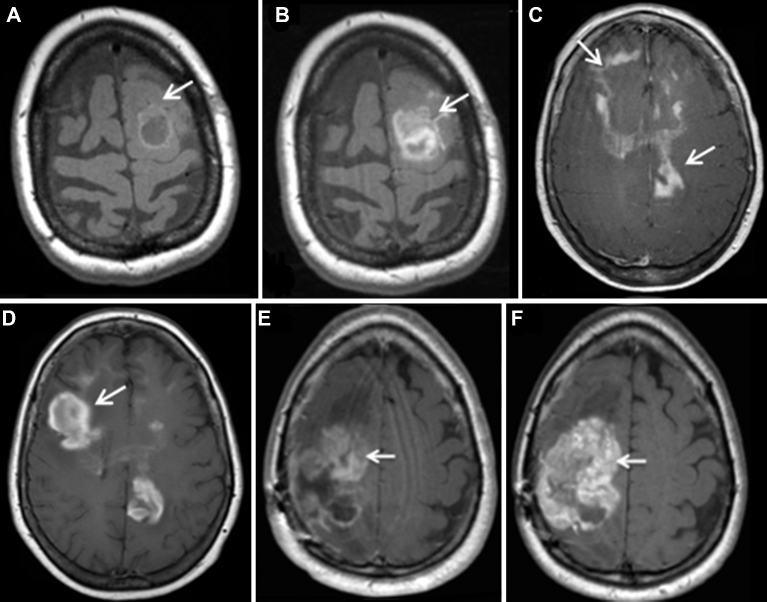

Ferumoxytol is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of anemia in adult patients with chronic kidney disease.41 Safety data from investigations in patients with chronic kidney disease have been used as a rationale that ferumoxytol could in principle also be safely used “off label” as an alternative contrast agent for MRI (Figure 4).32,34,35,39,42,43 Late ferumoxytol enhancement is useful in the evaluation of primary and secondary CNS neoplasms, lymphoproliferative disorders, demyelination, and vascular diseases (Figure 5).32,34,35,39,42,43 Limitations of ferumoxytol as a contrast agent include lack of reimbursement, inadequate long-term safety data, frequent need for multiple imaging sessions, and uncommonly delayed enhancement that may result in misinterpretations. On March 30, 2015, the FDA added a boxed warning for ferumoxytol, highlighting the risk of hypersensitivity reactions, the need for observation post administration, and the need for staff and medications to be available to immediately treat any reactions. The rate of adverse events with ferumoxytol has remained the same since its approval for use as an iron replacement on June 30, 2009 (http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm440138.htm). According to the FDA, ferumoxytol has been administered over 1 million times, and there have been 79 reported cases of serious hypersensitivity, including 18 fatalities. This rate is comparable to that of ionic iodinated contrast media44 and 10 times higher than that of GBCA45 and nonionic iodinated contrast media.44 Extra care is suggested in elderly patients with multiple or serious medical conditions and in patients with multiple drug allergies. A lower injection rate is also suggested, although there are no data available that injection rate has any impact on the frequency or severity of reactions. The safety of GBCA has also received renewed attention in the face of new data showing gadolinium deposition in the basal ganglia and dentate nucleus in a dose-dependent fashion and even rarely after a single GBCA infusion. In principle, this may have clinical relevance in humans,46 as delayed neurological toxicity after GBCA has been shown in animal models.47,48

FIGURE 4.

Anatomical gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) vs ferumoxytol-enhanced MRI in 3 tumor types. Illustrated is a small molecular weight extracellular contrast agent (GBCA) vs a 22-nm iron oxide nanoparticle that targets and is endocytosed by inflammatory cells but is not taken up by tumor cells except in the case of lymphoma. A, Axial T1W MRI images in a patient with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder show a mildly enhancing, partially cystic lesion in the left frontal lobe on Gd-MRI (arrows). B, Axial T1W FeMRI of the same patient shows a larger lobulated nodular enhancement (arrows). C, Axial T1W GdMRI of primary central nervous system lymphoma shows nodular and linear areas of enhancement in the frontal and parietal lobes (arrows) and corpus callosum compared to increasing nodular enhancement on axial T1W FeMRI D. Axial T1W GdMRI E shows heterogeneous enhancement in metastatic leiomyosarcoma (arrow) compared to F greater enhancement on axial T1W FeMRI (arrow).

FIGURE 5.

A, T1-weighted imaging; B, T1-weighted imaging post gadolinium-based contrast agent shows a large periventricular enhancing tumor in a 20-yr-old male; C, T1-weighted imaging 24 h post-ferumoxytol infusion shows much more extensive and heterogeneous uptake. After biopsy, this lesion was confirmed to represent lymphoma. Differences between ferumoxytol and gadolinium-based contrast agent enhancement are still under investigation, but different molecule size and uptake by macrophages are certainly important factors.

In children, the 3 major techniques for measuring permeability and perfusion, DSC, DCE, and arterial spin labeling, have being used in clinical care and research. Each has demonstrated value in assessment of neovascularity and integrity of the NVU with regard to preoperative histological grading of tumors and in identifying favorable and unfavorable treatment responses.21 A dual contrast agent (ferumoxytol and GBCA) single imaging session in children has been tested and is feasible, safe, and apparently useful for assessing tumor perfusion and permeability characteristics in children (Figure 6).49

FIGURE 6.

A, T1-weighted imaging; T2-weighted MRI. Reprinted from Thompson et al,49 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2012, with permission of Springer. B, Post-gadolinium-based contrast agent shows residual enhancing tumor (arrow) in a 10-yr-old girl with medulloblastoma. C, Dynamic susceptibility contrast–cerebral blood volume map using ferumoxytol bolus shows high vascularity of this area. D, Improved anatomical delineation of the highly vascular tumor is seen on the steady-state map.

The modeling element remains essential to the conversion of imaging data into quantitative permeability and perfusion parameters. Most current approaches are variations of tracer kinetics with basic assumptions about volume of distribution and compartments.50 The most commonly utilized classic graphical approach was described in the 1980s.51 In 1991, Tofts and Kermode52 described their analysis for dynamic gadolinium-based imaging, which is the most commonly used approach for modeling MRI contrast enhancement and is frequently implemented in research and clinical postprocessing packages. Significant variations remain in both scanner vendor and postprocessing vendor implementation, though efforts by the Radiological Society of North America's Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance to better standardize these methods are ongoing. In some instances, for example, active lesions of multiple sclerosis, qualitative evaluation of DCE-MRI data may also provide insight into disease mechanisms.53

One recent study54 has developed an advanced method using individual arterial input function, improved spatial resolution, improved signal-to-noise ratio, and a new software (“ROCKETSHIP”) to determine simultaneously BBB integrity in different gray and white matter regions in the living human brain. These investigators showed that BBB breakdown during normal aging begins in the hippocampus, a region critical for learning and memory, and that BBB breakdown in the hippocampus worsens with mild cognitive impairment and correlates with injury to BBB-associated pericytes.

DCE-CT has been used for evaluating permeability, mostly in stroke and tumor imaging.55-57 CT perfusion in combination with DCE-MRI quantifies the permeability surface product of the BBB, which measures the leakage rate of solutes in blood through the compromised BBB. BBB permeability has been serially measured using this method in animal models and stroke patients, with implications for prediction of hemorrhagic transformation, prediction in ischemic stroke, primary intracerebral hemorrhage, poststroke reperfusion injury, and long-term cognitive/dementia manifestations.58

There is an extensive body of literature describing cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR), an indirect measurement of the coupling between neuron and vasculature, using hypercapnia and acetazolamide. Acetazolamide is a potent dilator of cerebral arterioles and has been used for CVR testing for decades.59-61 Alternatively, hypercapnia can also be used as a cerebroarterial dilator, with advantages and disadvantages compared to acetazolamide.62 CVR provides information about the hemodynamics and pathophysiology of cerebrovascular diseases based on the principle that applying a vasodilating stimuli to the brain vasculature, while at the same time measuring CBF, will cause a relative increase in CBF due to decreasing impedance of the brain vasculature, directly reflecting the spontaneous tone of the arterioles. Changes in blood flow velocities can be measured using transcranial Doppler63,64 or with CT/MRI perfusion maps.65,66 CVR has been extensively used in the evaluation of patients with carotid and cerebral vascular disease.65,67-69 This has also been studied in less common indications, such as vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage,63,70 sleep apnea,71 and functional evaluation with MRI.72

Resting State Functional MRI

Many centers are routinely using functional MRI (fMRI) in the preoperative evaluation of lesions near important regions of the brain, such as motor and language cortex, as well as in the definition of laterality of language areas. The NVC is the basic principle of fMRI, which measures the relative concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin (BOLD) in blood vessels and tissues, indirectly measuring regional brain activity, which may be disrupted within a pathological NVU. When released, certain neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, can promote dilatation of cerebral blood vessels by triggering vasoactive molecules from both neurons and glial cells.73

In a number of neurological conditions, including stroke, glioma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cortical spreading depolarizations, brain injury, hypertension, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer and Parkinson disease, neuro-glio-vascular coupling may be altered or dysfunctional, altering the relationship between neuronal activity and changes in blood oxygenation.73

While fMRI is used for detection of activity during a task, measurements at rest also provide information concerning the structure and function of the NVU. Resting state (rs)-fMRI also relies on NVC to determine neural activity. Spatially distinct brain regions corresponding to intrinsic brain networks demonstrate synchronous changes in BOLD signal.74,75 These networks are reproducible within and across subjects.76 Expertise in the dynamics of NVC is critical for accurate interpretation of fMRI in various diseases in which uncoupling may occur, such as in the vicinity of brain tumors.77 In rs-fMRI, a brain region demonstrating aberrant NVC manifests as an abnormal depiction of network topology. rs-fMRI may be more feasible than commonly employed clinical task-related techniques such as breathholding in children, and it may also have value in unresponsive patients.

The possibility of rs-fMRI being unaffected by neurovascular uncoupling due to molecular differences underpinning the BOLD response at rest vs during a task has been raised. Although presence of neurovascular uncoupling is not specifically described in rs-fMRI, the similarity of the NVC between rs-fMRI and task-fMRI has been demonstrated,78 indicating that rs-fMRI is affected by neurovascular uncoupling in the presence of pathology. Recently, alternatives to BOLD-based functional imaging have been proposed, including ferumoxytol-enhanced rs-fMRI.79,80

CONCLUSION

Knowledge of the normal function and structure of the NVU is essential for understanding diseases involving the CNS. Imaging the NVU has been the subject of basic science and translational research activities for some time now, and recent and ongoing advances will help to incorporate several of these into clinical practice, where they will undoubtedly influence patient care. CT, MRI, and PET biomarker permeability and perfusion measurements offer noninvasive tools to indirectly measure NVU function in many disease states, and neuroradiologists, familiar with advances in contrast media (such as ferumoxytol), techniques, and postprocessing, will be the first to adopt these techniques.

Disclosures

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health grants R13 CA086959, NS053468, and CA137488-15S1, in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E, and by the Walter S. and Lucienne Driskill Foundation, all to EAN. Funding by P01 CA042045 went to KAK. HED was funded by R01 HD081123A and R21 CA176519. HS received funding support from the RSNA Carestream Health Research Scholar Grant and ImmunArray. DSR is funded by the Intramural Research Programs of the NINDS and has received research funding from Vertex Pharmaceuticals and the Myelin Repair Foundation. The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

Notes

This work was presented at the 21st Annual Blood-Brain Barrier Consortium Meeting in collaboration with the International Brain Barriers Society, March 19-21, 2015, Stevenson, Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harder DR, Zhang C, Gebremedhin D. Astrocytes function in matching blood flow to metabolic activity. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stanimirovic DB, Friedman A. Pathophysiology of the neurovascular unit: disease cause or consequence? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(7):1207-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57(2):178-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zlokovic BV. Cerebrovascular permeability to peptides: manipulations of transport systems at the blood-brain barrier. Pharm Res. 1995;12(10):1395-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Filosa JA. Vascular tone and neurovascular coupling: considerations toward an improved in vitro model. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2(16):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paolinelli R, Corada M, Orsenigo F, Dejana E. The molecular basis of the blood brain barrier differentiation and maintenance. Is it still a mystery? Pharmacol Res. 2011;63(3):165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daneman R. The blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(5):648-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19(12):1584-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daneman R, Prat A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7(1):a020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muoio V, Persson PB, Sendeski MM. The neurovascular unit - concept review. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2014;210(4):790-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muldoon LL, Alvarez JI, Begley DJ et al. . Immunologic privilege in the central nervous system and the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(1):13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naik P, Cucullo L. In vitro blood-brain barrier models: current and perspective technologies. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(4):1337-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y et al. . A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(147):147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Winkler EA, Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(11):1398-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iqbal U, Albaghdadi H, Luo Y et al. . Molecular imaging of glioblastoma multiforme using anti-insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 single-domain antibodies. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(10):1606-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barrio JR, Small GW, Wong KP et al. . In vivo characterization of chronic traumatic encephalopathy using [F-18]FDDNP PET brain imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(16):E2039-E2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sood RR, Taheri S, Candelario-Jalil E, Estrada EY, Rosenberg GA. Early beneficial effect of matrix metalloproteinase inhibition on blood-brain barrier permeability as measured by magnetic resonance imaging countered by impaired long-term recovery after stroke in rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(2):431-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taheri S, Candelario-Jalil E, Estrada EY, Rosenberg GA. Spatiotemporal correlations between blood-brain barrier permeability and apparent diffusion coefficient in a rat model of ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li M, Dai FR, Du XP, Yang QD, Zhang X, Chen Y. Infusion of BDNF into the nucleus accumbens of aged rats improves cognition and structural synaptic plasticity through PI3K-ILK-Akt signaling. Behav Brain Res. 2012;231(1):146-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pishko GL, Muldoon LL, Pagel MA, Schwartz DL, Neuwelt EA. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade alters magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers of vascular function and decreases barrier permeability in a rat model of lung cancer brain metastasis. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2015;12(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heye AK, Culling RD, Valdes Hernandez Mdel C, Thrippleton MJ, Wardlaw JM. Assessment of blood-brain barrier disruption using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. A systematic review. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;6:262-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoffmann A, Bredno J, Wendland MF et al. . Validation of in vivo magnetic resonance imaging blood-brain barrier permeability measurements by comparison with gold standard histology. Stroke. 2011;42(7):2054-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Knight RA, Nagaraja TN, Ewing JR. Letter by Knight et al regarding article, “Validation of in vivo magnetic resonance imaging blood-brain barrier permeability measurements by comparison with gold standard histology”. Stroke. 2011;42(10):e568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cramer SP, Larsson HB. Accurate determination of blood-brain barrier permeability using dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI: a simulation and in vivo study on healthy subjects and multiple sclerosis patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(10):1655-1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taheri S, Rosenberg GA, Ford C. Quantification of blood-to-brain transfer rate in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2013;2(2):124-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hart BL, Taheri S, Rosenberg GA, Morrison LA. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI evaluation of cerebral cavernous malformations. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4(5):500-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Candelario-Jalil E, Thompson J, Taheri S et al. . Matrix metalloproteinases are associated with increased blood-brain barrier opening in vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1345-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shinohara RT, Crainiceanu CM, Caffo BS, Gaitan MI, Reich DS. Population-wide principal component-based quantification of blood-brain-barrier dynamics in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1430-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Law M, Yang S, Babb JS et al. . Comparison of cerebral blood volume and vascular permeability from dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging with glioma grade. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(5):746-755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Provenzale JM, Wang GR, Brenner T, Petrella JR, Sorensen AG. Comparison of permeability in high-grade and low-grade brain tumors using dynamic susceptibility contrast MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(3):711-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shiroishi MS, Castellazzi G, Boxerman JL et al. . Principles of T2 *-weighted dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI technique in brain tumor imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(2):296-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Neuwelt EA, Hamilton BE, Varallyay CG et al. . Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxides (USPIOs): a future alternative magnetic resonance (MR) contrast agent for patients at risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF)? Kidney Int. 2009;75(5):465-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gahramanov S, Varallyay C, Tyson RM et al. . Diagnosis of pseudoprogression using MRI perfusion in patients with glioblastoma multiforme may predict improved survival. CNS Oncol. 2014;3(6):389-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gahramanov S, Muldoon LL, Varallyay CG et al. . Pseudoprogression of glioblastoma after chemo- and radiation therapy: diagnosis by using dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging with ferumoxytol versus gadoteridol and correlation with survival. Radiology. 2013;266(3):842-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gahramanov S, Raslan AM, Muldoon LL et al. . Potential for differentiation of pseudoprogression from true tumor progression with dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging using ferumoxytol vs. gadoteridol: a pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(2):514-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nasseri M, Gahramanov S, Netto JP et al. . Evaluation of pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma multiforme using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging with ferumoxytol calls RANO criteria into question. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(8):1146-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Varallyay CG, Nesbit E, Fu R et al. . High-resolution steady-state cerebral blood volume maps in patients with central nervous system neoplasms using ferumoxytol, a superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(5):780-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christen T, Ni W, Qiu D et al. . High-resolution cerebral blood volume imaging in humans using the blood pool contrast agent ferumoxytol. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(3):705-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farrell BT, Hamilton BE, Dosa E et al. . Using iron oxide nanoparticles to diagnose CNS inflammatory diseases and PCNSL. Neurology. 2013;81(3):256-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Essig M, Nguyen TB, Shiroishi MS et al. . Perfusion MRI: the five most frequently asked clinical questions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(3):W495-W510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spinowitz BS, Kausz AT, Baptista J et al. . Ferumoxytol for treating iron deficiency anemia in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(8):1599-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dosa E, Tuladhar S, Muldoon LL, Hamilton BE, Rooney WD, Neuwelt EA. MRI using ferumoxytol improves the visualization of central nervous system vascular malformations. Stroke. 2011;42(6):1581-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klenk C, Gawande R, Uslu L et al. . Ionising radiation-free whole-body MRI versus (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scans for children and young adults with cancer: a prospective, non-randomised, single-centre study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):275-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Katayama H, Yamaguchi K, Kozuka T, Takashima T, Seez P, Matsuura K. Adverse reactions to ionic and nonionic contrast media. A report from the Japanese Committee on the Safety of Contrast Media. Radiology. 1990;175(3):621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prince MR, Zhang H, Zou Z, Staron RB, Brill PW. Incidence of immediate gadolinium contrast media reactions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(2):W138-W143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF et al. . Intracranial gadolinium deposition after contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015;275(3):772-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roman-Goldstein SM, Barnett PA, McCormick CI, Ball MJ, Ramsey F, Neuwelt EA. Effects of gadopentetate dimeglumine administration after osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption: toxicity and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12(5):885-890. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kanal E, Tweedle MF. Residual or retained gadolinium: practical implications for radiologists and our patients. Radiology. 2015;275(3):630-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thompson EM, Guillaume DJ, Dosa E et al. . Dual contrast perfusion MRI in a single imaging session for assessment of pediatric brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2012;109(1):105-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Peters AM. Fundamentals of tracer kinetics for radiologists. Br J Radiol. 1998;71(851):1116-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Patlak CS, Blasberg RG. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5(4):584-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tofts PS, Kermode AG. Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability and leakage space using dynamic MR imaging. 1. Fundamental concepts. Magn Reson Med. 1991;17(2):357-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gaitan MI, Shea CD, Evangelou IE et al. . Evolution of the blood-brain barrier in newly forming multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(1):22-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Montagne A, Barnes SR, Sweeney MD et al. . Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron. 2015;85(2):296-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nguyen GT, Coulthard A, Wong A et al. . Measurement of blood-brain barrier permeability in acute ischemic stroke using standard first-pass perfusion CT data. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;2:658-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ozkul-Wermester O, Guegan-Massardier E, Triquenot A, Borden A, Perot G, Gerardin E. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability on perfusion computed tomography predicts hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(1-2):45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Terada T, Nambu K, Hyotani G et al. . A method for quantitative measurement of cerebral vascular permeability using X-ray CT and iodinated contrast medium. Neuroradiology. 1992;34(4):290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. d’Esterre CD, Fainardi E, Aviv RI, Lee TY. Improving acute stroke management with computed tomography perfusion: a review of imaging basics and applications. Transl Stroke Res. 2012;3(2):205-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Settakis G, Molnar C, Kerenyi L et al. . Acetazolamide as a vasodilatory stimulus in cerebrovascular diseases and in conditions affecting the cerebral vasculature. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(6):609-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sorteberg W, Lindegaard KF, Rootwelt K et al. . Effect of acetazolamide on cerebral artery blood velocity and regional cerebral blood flow in normal subjects. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;97(3-4):139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vorstrup S, Henriksen L, Paulson OB. Effect of acetazolamide on cerebral blood flow and cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen. J Clin Invest. 1984;74(5):1634-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ringelstein EB, Van Eyck S, Mertens I. Evaluation of cerebral vasomotor reactivity by various vasodilating stimuli: comparison of CO2 to acetazolamide. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12(1):162-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bothun ML, Haaland OA, Logallo N, Svendsen F, Thomassen L, Helland CA. Cerebrovascular reactivity after treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms–A transcranial Doppler sonography and acetazolamide study. J Neurol Sci. 2016;363:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gur AY, Bornstein NM. TCD and the Diamox test for testing vasomotor reactivity: clinical significance. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2001;35(suppl 3):51-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hartkamp NS, Bokkers RP, van Osch MJ, de Borst GJ, Hendrikse J. Cerebrovascular reactivity in the caudate nucleus, lentiform nucleus and thalamus in patients with carotid artery disease. J Neuroradiol. 2017;44(2):143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wintermark M, Sincic R, Sridhar D, Chien JD. Cerebral perfusion CT: technique and clinical applications. J Neuroradiol. 2008;35(5):253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fujimoto K, Matsumoto Y, Oikawa K et al. . Cerebral hyperperfusion after revascularization inhibits development of cerebral ischemic lesions due to artery-to-artery emboli during carotid exposure in endarterectomy for patients with preoperative cerebral hemodynamic insufficiency: revisiting the “impaired clearance of emboli” concept. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Selvarajah D, Hughes T, Reeves J et al. . A preliminary study of brain macrovascular reactivity in impaired glucose tolerance and type-2 diabetes: Quantitative internal carotid artery blood flow using magnetic resonance phase contrast angiography. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2016;13(5):367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yoshida J, Ogasawara K, Chida K et al. . Preoperative prediction of cerebral hyperperfusion after carotid endarterectomy using middle cerebral artery signal intensity in 1.5-tesla magnetic resonance angiography followed by cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide using brain perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography. Neurol Res. 2016;38(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mourier KL, George B, Raggueneau JL et al. . [Value of the measurement of cerebral blood flow before and after diamox injection in predicting clinical vasospasm and final outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage]. Neurochirurgie. 1991;37(5):318-322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Burgess KR, Lucas SJ, Shepherd K et al. . Influence of cerebral blood flow on central sleep apnea at high altitude. Sleep. 2014;37(10):1679-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Siero JC, Hartkamp NS, Donahue MJ et al. . Neuronal activation induced BOLD and CBF responses upon acetazolamide administration in patients with steno-occlusive artery disease. NeuroImage. 2015;105:276-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hall CN, Howarth C, Kurth-Nelson Z, Mishra A. Interpreting BOLD: towards a dialogue between cognitive and cellular neuroscience. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371(1705):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(27):9673-9678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kalcher K, Huf W, Boubela RN et al. . Fully exploratory network independent component analysis of the 1000 functional connectomes database. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F et al. . Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(37):13848-13853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zaca D, Jovicich J, Nadar SR, Voyvodic JT, Pillai JJ. Cerebrovascular reactivity mapping in patients with low grade gliomas undergoing presurgical sensorimotor mapping with BOLD fMRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(2):383-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bruyns-Haylett M, Harris S, Boorman L, Zheng Y, Berwick J, Jones M. The resting-state neurovascular coupling relationship: rapid changes in spontaneous neural activity in the somatosensory cortex are associated with haemodynamic fluctuations that resemble stimulus-evoked haemodynamics. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38(6):2902-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. D’Arceuil H, Coimbra A, Triano P et al. . Ferumoxytol enhanced resting state fMRI and relative cerebral blood volume mapping in normal human brain. Neuroimage. 2013;83:200-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Qiu D, Zaharchuk G, Christen T, Ni WW, Moseley ME. Contrast-enhanced functional blood volume imaging (CE-fBVI): enhanced sensitivity for brain activation in humans using the ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide agent ferumoxytol. Neuroimage. 2012;62(3):1726-1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Toth GB, Varallyay CG, Horvath A. Current and potential imaging applications of ferumoxytol for magnetic resonance imaging. Kidney Int. 2017;92(1):47-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]