Abstract

Richard K Shields, PT, PhD, has contributed to the physical therapy profession as a clinician, scientist, and academic leader (Fig. 1).

Dr Shields is professor and department executive officer of the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science at the University of Iowa. He completed a certificate in physical therapy from the Mayo Clinic, an MA degree in physical therapy, and a PhD in exercise science from the University of Iowa.

Dr Shields developed a fundamental interest in basic biological principles while at the Mayo Clinic. As a clinician, he provided acute inpatient care to individuals with spinal cord injury. This clinical experience prompted him to pursue a research career exploring the adaptive plasticity of the human neuromusculoskeletal systems. As a scientist and laboratory director, he developed a team of professionals who understand the entire disablement model, from molecular signaling to the psychosocial factors that impact health-related quality of life. His laboratory has been continuously funded by the National Institutes of Health since 2000 with more than  15 million in total investigator-initiated support. He has published 110 scientific papers and presented more than 300 invited lectures.

15 million in total investigator-initiated support. He has published 110 scientific papers and presented more than 300 invited lectures.

A past president of the Foundation for Physical Therapy, Dr Shields is a Catherine Worthingham Fellow of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and has been honored with APTA’s Marian Williams Research Award, the Charles Magistro Service Award, and the Maley Distinguished Research Award. He also received the University of Iowa's Distinguished Mentor Award, Collegiate Teaching Award, and the Regents Award for Faculty Excellence.

Dr Shields is a member of the National Advisory Board for Rehabilitation Research and serves as the liaison member on the Council to the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development.

Dr Sharon Dunn, our esteemed APTA president, you bring all that is good to our profession. Thank you for the kind introduction. To the Board of Directors, thank you for your support of my nomination and for your unwavering dedication and service. We are fortunate to have a national organization, APTA [American Physical Therapy Association], that epitomizes professionalism, and that starts at the top. Our Chief Executive Officer, Dr. Justin Moore, is a distinguished graduate from the University of Iowa and a longtime colleague and friend. We are proud of all you have accomplished and thank you for all that you do for our profession.

It is an honor to be nominated by a group of people for whom I have such admiration. Charles Magistro, a visionary who gave so much to our profession, wrote a letter on my behalf during the final months of his life. For those who never met Charles, you have missed getting to know a great person. We owe him much, and I know he is tuned in for this lecture. To my children, Bridget, Connor, and Ryan, thank you for making me so proud of you; and to Kolleen, my wife: I would not be here without you.

In 1921, our professional society formed under the able leadership of Mary McMillan, a pioneer who fought for what she believed in. In just 4 years, we will enjoy the 100-year anniversary of our physical therapy organization. We have much to be proud of as we move our profession forward into the next 100 years. I cannot think of a better team to be associated with than APTA.

For 36 years, I have been surrounded by such outstanding people in our profession. My colleagues from Iowa are remarkable individuals who have always taken responsibility for their actions, respected each other, and been honest and caring professionals. I thank you for your support and for putting up with my obsession to measure everything.

Recently, I learned that 13% of all previous Mary McMillan lecturers attended the University of Iowa, a remarkable number. What a compliment it is to the Roy and Lucille Carver College of Medicine for investing so heavily in physical therapy since 1942.

Physical Therapy and Biological Aging

Time, as depicted by the hourglass (Fig. 2), has always been a fascinating measurement to me. It reminds us that we are all just getting older and time is slipping away and we are just specks of dust, falling at some fixed rate, through the fingers of time—almost as if we have no control of our destiny.

Figure 2.

“As a physical therapist, I believe that we change time. We routinely turn over the hourglass and give patients a new lease on life. Quite simply, our interventions… are powerful regulators of genes that activate the energy systems that can reduce the rate that cells and tissues age.” Photo credit: David Braun Photography Inc.

Figure 1.

Richard Shields, PT, PhD, presenting the 48th Mary McMillan Lecture at APTA’s NEXT Conference & Exposition, June 22, 2016, in Boston, Massachusetts. Photo credit: David Braun Photography Inc.

But as a physical therapist, I believe that we change time. We routinely turn over the hourglass and give patients a new lease on life. Quite simply, our interventions, if appropriately prescribed and adhered to, are powerful regulators of genes that activate the energy systems that can reduce the rate that cells and tissues age.

Science now supports that the brain, muscle, bone, cartilage, cardiac, inflammatory, and vascular tissues all respond to our prescribed movements in ways that the pharmaceutical industry can only dream about.

Our knowledge about movement has come a long way from the work published by Dr William Collier in 1893, when he wrote, “In short, ample evidence exists which points to the conclusion that frequently repeated muscular effort is a potent agent in the production of heart disease.”1

Today, whether for a preterm infant or a frail elder, we know that we affect the rate of cellular and tissue biological aging through our movement-based interventions. Although as clinicians we most often think about strength, endurance, coordination, and function, the cellular changes that we trigger are the most fundamental ways that we improve the health and well-being of humankind.

The appealing part of our profession is that our interventions are natural and seem to reset the aging clock of the human body. Cells and tissues biologically age when their energy systems fail, regardless of their chronological age. My point is that accelerated tissue aging occurs at any age whenever we are forced to minimize our movement and energy homeostasis is disrupted. When the natural plasticity and adaptive healing capability of our tissues cannot keep pace with a physiological, emotional, or social stress, we witness disease, pain, injury, loss of function, or need for surgery.

Genes that respond favorably to movement, exercise, load, length, environmental stress, and oxidative stress have been well conserved in humans for millions of years. What does “well conserved” mean? It means that our genes were selected long ago because of their value to the entire human body; these advantageous genes were passed on to future generations. Over many years, humans developed a gene pool that offered benefit and protection to those who move, enabling survival even in very challenging times.

Frequent movement is therefore an important strategy to promote the expression of healthy genes and repress the expression of genes that can damage tissues at any time during life.

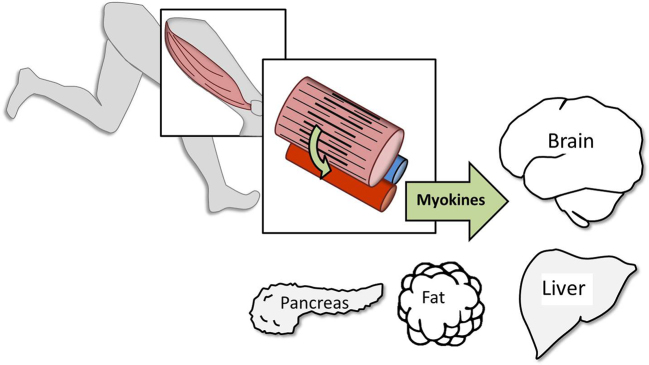

As each of you know, skeletal muscle in humans developed an enormous oxidative capacity to produce energy so that movement was sustainable for long periods. What we did not know, when I was in school, is that skeletal muscle is a powerful endocrine organ that releases substances called myokines directly into the blood stream2,3 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Exercising skeletal muscles secrete powerful endocrine molecules called myokines into the blood. Myokines help regulate a number of important target tissues including the brain, creating an important link between habitual physical activity, biological aging of cells and tissues, and the onset of chronic disease.

When these substances reach their target tissues, they regulate genes in cells throughout the entire body—and yes, this includes the brain, and they directly influence neuroplasticity.4 It is no longer acceptable to think of a contracting muscle as a mere force vector.

If you are listening to me right now, reflecting on the words I say, and putting any part of it into memory, then you have upregulated these same oxidative pathways in your brain cells. While you are working to follow my words, the nerve cells in your brain are rapidly manufacturing transmitters to enhance synapses to assist you in retrieving this information in the future.

Likewise, when a patient concentrates to perform a novel movement, their neurons up-regulate the oxidative machinery to coordinate muscle synergists to optimize movement.

This degree of up-regulation of oxidative metabolism in the brain is something that you initiate every day as you engage and connect with your patients. The optimal movement that you teach will not be replicated frequently enough to be effective if you do not connect with your clients, affect their memory, and influence their behavior.

The genes that regulate these oxidative energy pathways in the mitochondria of cells are the focus of much of my own research today. Yes, this pathway, the Krebs Cycle, which many of you still have nightmares about, was discovered by Hans Krebs with work he began in 1932 and for which he won the Nobel Prize.5

But it was the person, Hans Krebs, who understood that the fallible and imaginative part of research, the part that never reaches the scientific literature, is so important in the discovery of real knowledge. He stated, “Those ignorant of the historical development of science are not likely ever to understand fully … scientific research.”6

Drs. Watson, Crick, Wilkins, and Franklin published the structure of DNA in 1953, exactly 1 year before I was born.7–9 Today, in my own laboratory, we routinely examine how various doses of human movements regulate the entire human genome and epigenome in people with limited capacity to move. Just 15 years ago, genomic analysis was just a dream, but today it is a reality.

These capabilities are laying the groundwork for physical therapists to dose movement in ways that we never considered possible. You have heard the statement that “exercise is medicine.” Although that may be true, I believe that “exercise is movement, and movement is physical therapy.” As we strive to integrate new knowledge into our field, precision physical therapy will emerge side by side with precision medicine.

When we hear words like “human performance,” we, as physical therapists, do not only think about scoring a touchdown, making a basket, or running faster. We also think about the 16-year-old adolescent with paralysis who is performing, like an elite gymnast, at her highest capacity as she is competing for a healthier and happier life. We know our treatments have the capacity to influence much more than just a game.

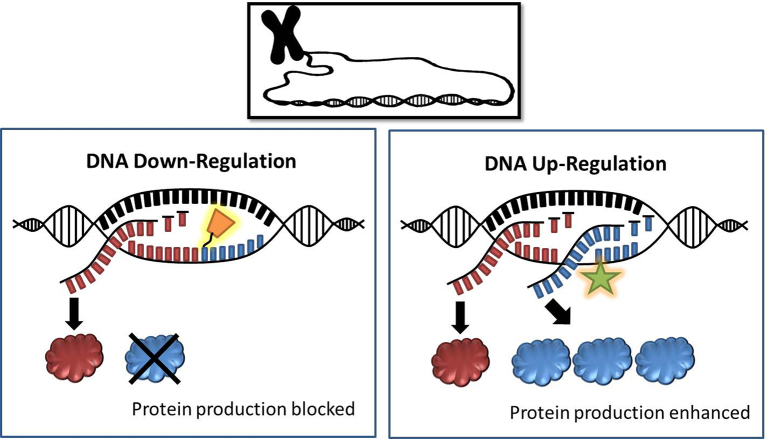

Our core scientific principles that govern the capacity for cells to respond to movement are the common threads that bind us together, regardless of our area of specialization, as we speak with one voice as one profession (Fig. 4). These are the core principles that every academic physical therapy program must honor and teach with care. In turn, our students must be able to articulate the molecular concepts with ease to the public and to other health care professionals.

Figure 4.

Core scientific principles for the physical therapy profession that govern the capacity for cells to respond to movement-based interventions.

We must never allow the number of academies, sections, specializations, residency programs, or academic physical therapy programs to weaken our message that our movement interventions “turn over the hourglass” and extend life for people with compromised health.

If we communicate across our professional organizational structure—at the academic level and at the clinical care level—our unified core message stays clear and our future is bright.

The Future We Embrace

The hourglass must be “turned over” as we aspire to meet our new visions. In a world with rapidly changing technology, shifting financial markets, changing health care policy, and uncertain political leadership, our adaptability as a profession will be paramount as we journey together to meet new challenges in the next decade.

We should all be optimistic because our profession's record of accomplishments is exceptional. In just 4 years, we will enjoy the 100-year anniversary of our organization. Do you realize that only 12% of the Fortune 500 companies that flourished in 1955 still have their doors open today? Two things seem to be present in those successful companies: a high-quality product and superb human experience.

We have a bold new vision “to transform society by optimizing movement to improve the human experience.”10 To realize this vision, I believe we must do 2 things, which I will cover in this lecture. First, we must journey into the micro-scale world of optimized movement through the lens of the human genome; second, we must visit the macro-scale world of the human experience with a focus on our patients and our students. In the end, I hope to challenge you to think about the future that we embrace as physical therapists.

The Power of Optimizing Movement

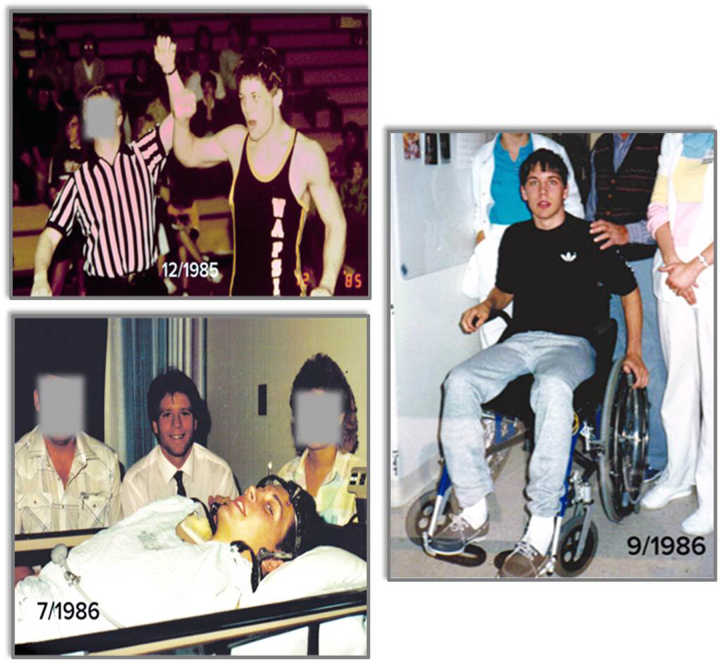

The words “optimizing movement,” as written in our vision statement, remind me of a patient that I managed over 30 years ago. In December 1985, a 16-year-old, “Mr J,” had his arm raised after winning a high school wrestling title in Iowa. Just 7 months later, I was raising Mr J’s arm to prevent contractures after he sustained a cervical spinal cord injury [SCI], paralyzing him from the neck down (Fig. 5). He had control of his deltoids, biceps, and radial wrist extensors, but no triceps; a classic C6 level injury.

Figure 5.

Mr J as a champion high school wrestler (top left), with Dr Shields in 1986 after sustaining C6 complete tetraplegia (bottom left), and after achieving independent mobility in a manual wheelchair (right).

We reminded Mr J that he was still an athlete even though he had control of less than 20% of his muscle mass. We explained to Mr J that he had a long life ahead of him and he needed to be vigilant with learning to optimize his movements if he wanted to maintain his health.

Mr J worked very hard, and he learned how to extend his elbows with his anterior deltoid muscles, a high-level optimized motor skill.11 He trained for the first year after his injury to become functionally independent. We explained to Mr J the importance of a manual wheelchair and that an electric wheelchair would rob him of a daily dose of activity that he needed to sustain his health. Although what I was saying sounded right, I had no evidence that regular activity with just 20% of his muscle mass could really keep him healthy over his lifetime.

Recently, Mr J returned to the University of Iowa and demonstrated the same tasks that he learned in physical therapy 30 years ago, still using a manual wheelchair, and performing these tasks each day [video available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj].

Remarkably, an individual with tetraplegia, approaching 50 years of age, maintained his function for 30 years. Importantly, Mr J appears healthier than many of us who have far more opportunities to move each day.

Although just a single case, Mr J illustrates the power of teaching someone to optimize movement, and also the power of longitudinal data, something we desperately need in physical therapy research today. We must plant the seeds of research today to harvest the science of tomorrow.

Health Care Dilemma

In the real world, we have a dilemma. Prospective payment plans and the associated cut in inpatient rehabilitation days preclude many people with disability—like Mr J—from ever reaching their human performance potential. In support of this view, life expectancy for a 25-year-old sustaining tetraplegia today is 2.5 years shorter than for a similar patient sustaining tetraplegia before the year 2004.12

We are accelerating the aging process for young people with tetraplegia today, rather than combating it.

Longitudinal data dating back to 1973 show that while acute care and inpatient rehabilitation days for people with tetraplegia have declined, secondary complications have increased.13

The increased prescription of electric wheelchairs as a standard of care for people with tetraplegia appears to be associated with poor health and quality of life.14

The opportunity to teach people to move is at the very core of what we do as physical therapists. Before our very eyes, the human performance potential of a whole generation of patients with C6 level tetraplegia appears to be vanishing.

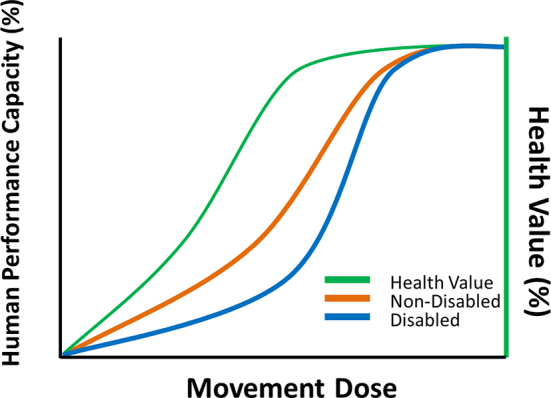

The relationship between movement dose and health value is complex,15 but important for us to understand as we strive to dose optimized movement for people with and without disability (Fig. 6). Mr J, our friend with tetraplegia, is represented by the blue curve on the plot. Mr J did not reap his full complement of health benefits until after he could move himself independently, which took nearly 1 year for him to become proficient; but that investment has served him well for over 30 years. What a small price to pay to have your health for a lifetime.

Figure 6.

Conceptual relationship between movement dose, human performance, and health value. Compared with a person without a disability (orange plot), Mr J required a higher dose of movement to experience improvements in his human performance capacity (blue plot). However, he rapidly experienced improved health value (green plot), even given his delayed timetable for improvements in human performance. The conceptual relationship and figure are adapted from Gabriel BM, Zierath JR. The limits of exercise physiology: from performance to health. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1000–1011, with permission from Elsevier.

Imagine for a moment if we introduced Mr J to an electric wheelchair 30 years ago, to check off a box, to meet his mobility need. Now imagine if Mr J returned to Iowa 30 years later as a man with obesity, suffering from diabetes and depression, and on a regimen of drugs, including powerful opioid pain medication.

When people like Mr J do not attain their full potential because of reduced inpatient rehabilitation days, it is the responsibility of all in our profession, as we are the experts in optimizing movement to enhance human performance.

While we all wait for the perfect data set to instruct us on how to negotiate new health care policies, we cannot ignore the power of singular, high-impact, cases. We must not forget what the human will can accomplish if given a chance. We cannot turn a blind eye and become overly docile or afraid to advocate for those whom we know need our services today.

We Are All Different

As we strive for congruence with clinical guidelines in our practice, we must appreciate the inherent differences that exist within our patients. People living with disease, injury, and/or immobility experience individualized genetic changes that affect their ability to respond to our treatments. The intensity and duration of our movement dose is rarely a “one size fits all.”

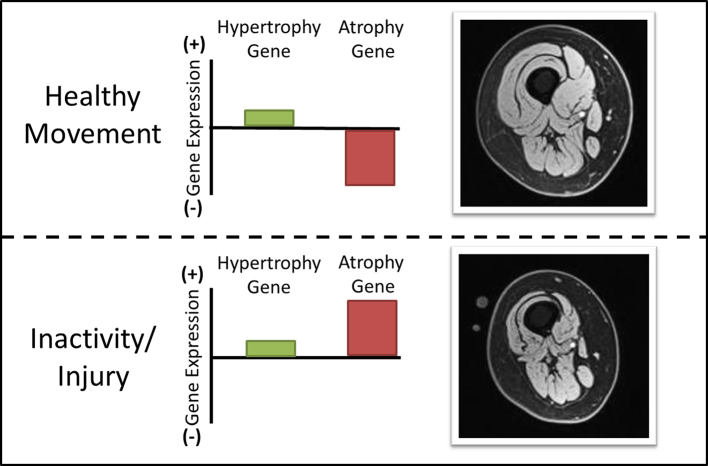

Allow me to illustrate this point using a simplistic model. We as physical therapists are the experts of how to induce muscle hypertrophy. So, let's consider 2 well-known gene signaling pathways that control the size of a skeletal muscle16: the hypertrophy gene pathway that promotes muscle protein synthesis, and the atrophy gene pathway that promotes protein breakdown, or proteolysis (Fig. 7). A severe environmental stress, like starvation, will up-regulate the atrophy gene to prevent muscle growth to preserve energy for the brain.

Figure 7.

Skeletal muscle size is determined by a balance between expression of hypertrophy gene pathways and atrophy gene pathways. After inactivity or injury, expression of atrophy genes increases many-fold. Epigenetic “tagging” may cause persistent up-regulation of these atrophy genes, even after restoration of normal activity. For some patients, persistent atrophy may implicate continued up-regulation of atrophy-promoting genes.

When a food source becomes available, a new hourglass has been turned over, with a new timeline to adjust the expression of the atrophy-promoting gene. Disease, injury, pain, sedentary lifestyle, malnutrition, or surgery all increase the expression of the atrophy gene, but with a timeline that may take months to years to repress for some people. Thus, the nonresponder in your clinic may have an overly expressed atrophy gene.

We all have witnessed persistent atrophy of the vastus medialis muscle long after exercise has resumed. Quite simply, the atrophy gene has been turned on and we cannot get it turned off. Knowing how to optimally “turn off” and “turn on” certain genes will form the basis for precision physical therapy in the future.

These biological genetic regulators, along with environmental and lifestyle factors, may in the future influence how many days of therapy and the type of treatment that we prescribe. For example, we may not want to prescribe eccentric contractions if we already know that the protein degradation gene pathway is already upregulated via the atrophy gene.

We are approaching the day when many of our patients will have their own personalized molecular profile [PMP] providing the biological predictors of cellular health. Coupled with sociobehavioral measurements and data from sensors that log movement, machine learning software will partition “big data” sets to classify patients as to who will be responders and nonresponders to our movement-based treatments. Quite simply, molecular surveillance will be a key method to classify and justify a more precise physical therapist intervention. Genome-based prediction rules are on our horizon.

Next year, the National Institutes of Health [NIH] will launch the “All of Us” research program, with the goal of recruiting 1 million people from various backgrounds.17 More than 1 billion dollars over 10 years has been appropriated to develop this novel longitudinal data set. Each of the 1 million enrollees will be followed, much like the Framingham study,18 and provide environmental data, lifestyle data, and molecular biomarkers for metabolism, aging, and epigenetics.

The “All of Us” research program has the potential to uncover important findings that can assist our mission to optimize movement. People in our profession must be involved with this innovative collection. In turn, we need faculty who can teach the next generation of students the concepts that they will need to play pivotal roles in precision physical therapy.

If we are caught watching the paint dry while these revolutionary studies facilitate the precision of pharmaceutical interventions, without similarly determining the precision of movement interventions, then we will have lost an important opportunity. If people like Mr J are captured in this new NIH-funded initiative, I am quite sure the power of his optimized movement will begin to be understood.

The Cyber Security of the Human Cell

What types of molecular concepts do contemporary physical therapists need to know? Let me illustrate this point with an analogy and then by using a single gene molecular example.

First, the industries that are best protected against a cyber-attack in the United States today are the energy companies. An attack on our energy grids would bring our country and the world to an immediate standstill. So, to maintain the health of our country, the Department of Homeland Security has prioritized protecting the health of all energy companies.19

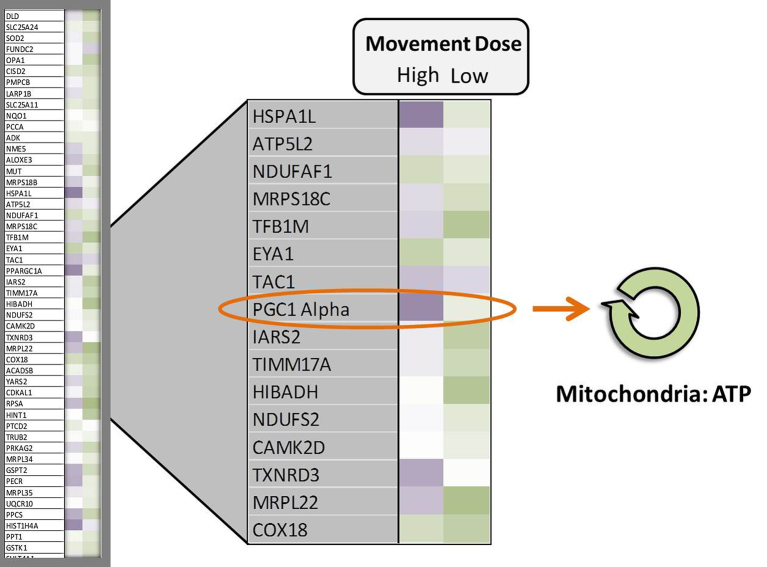

Likewise, to maintain the health of our patients, we must protect the energy-generating centers of each cell, the mitochondria. These energy plants are at the root of many diseases, damage to tissues, and resistance to healing.20 Because we are made up of activity-regulated genes, the mitochondria malfunction when we experience reduced movement. Recent research has uncovered a powerful gene called peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha, or PGC1 alpha, the “homeland security gene” for the human cell, which regulates the health of the mitochondria.

Much like the conductor of an orchestra leading all instruments into a crescendo of harmonious sound, PGC1 alpha turns up the volume on hundreds of other genes that affect oxidative energy production in human cells;21-23 yes, genes that are the foundation for the dreaded Krebs Cycle.

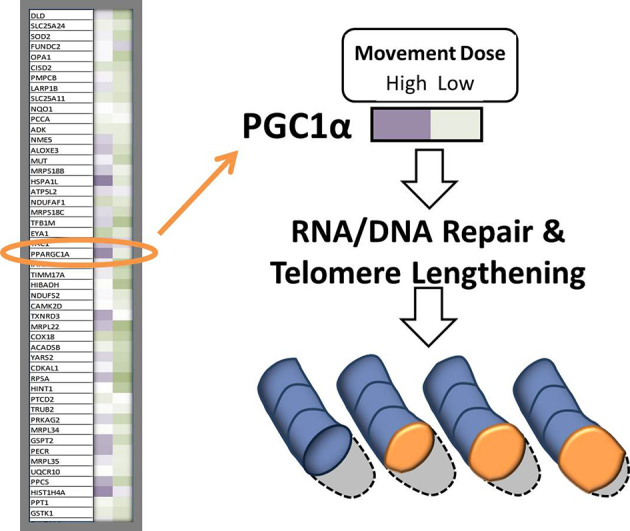

When we explored the 20,000 genes from Mr J’s genome, we illustrated that we can up-regulate the PGC1 alpha gene over 10 times its normal level with certain doses of muscle activity (Fig. 8). Notice the darker purple color of the gene map showing the up-regulation of the PGC1 alpha gene just 3 hours after 1 dose of movement as compared with a lower dose. With regular movement, the PGC1 alpha gene becomes perpetually upregulated, developing a “molecular memory.”21

Figure 8.

Representative example of a gene-array “heat map” for a patient with spinal cord injury who engaged in two doses of a movement intervention. Dark, medium, and light purple represent high, moderate, and low levels of gene up-regulation, respectively. Dark, medium, and light green represent high, moderate, and low levels of gene down-regulation, respectively. White represents no change from the pretraining baseline. Appropriately dosed movement interventions strongly up-regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1 alpha), a “master” gene that exerts widespread effects on gene networks that regulate cell metabolism. Through a multitude of downstream pathways, PGC1 alpha promotes mitochondrial replication and function, telomere length preservation, and epigenetic tagging of metabolic genes. ATP = adenosine triphosphate.

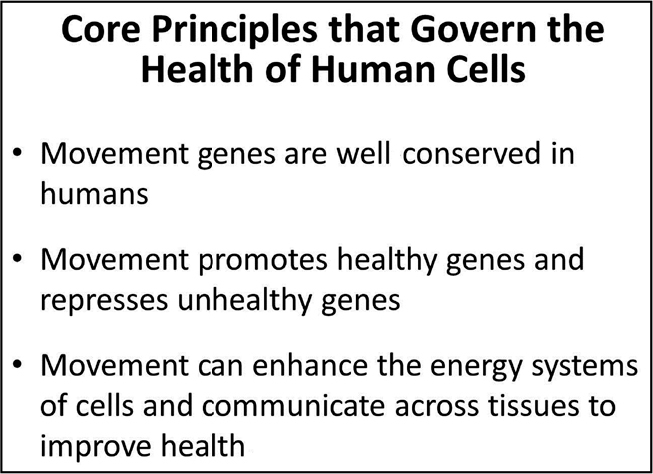

A repetitive healthy environmental stimulus, like movement—that promotes a gene that improves health and holds that promotion in memory—is the field of epigenetics.24 The epigenome oversees the genome and is relevant to physical therapists because our treatments are repetitive and typically prescribed for long time periods. When the epigenome “tags” a healthy gene to promote it, like the PGC1 alpha gene, there is a “protective memory” that enhances cellular energy function even if you suddenly have a period of unexpectedly reduced activity (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Illustration of epigenetic regulation of the genome. Epigenetic “tagging” of DNA can either block or enhance the transcription of genes and the production of encoded proteins.

When we repetitively suppress or “turn down” a healthy gene by disease or reduced movement, we enhance a process called “methylation” and accelerate the age of tissues.25 The overall aging clock of humans can now be estimated by a blood test to determine a methylation score26—or, in more practical terms, we can now estimate how many healthy genes are getting turned down as a function of age, injury, immobility, or disease. It is our role as physical therapists to prescribe interventions that turn these healthy genes back on to extend the life of the cells.

We are just at the cusp of characterizing how various doses of movement or lack of movement can impact the epigenome.

As previously mentioned, the gene PGC1 alpha is like an orchestra conductor; when it is upregulated epigenetically, the downstream effects are widespread. Just this year, it was discovered that the PGC1 alpha gene, upregulated by exercise, influenced the “aging clock” by triggering processes that preserve the length of telomeres.27

Telomeres are the specialized structures at the end of chromosomes that protect the DNA when the cell divides. They are known to shorten with age, causing damage to DNA and ultimately cell death.

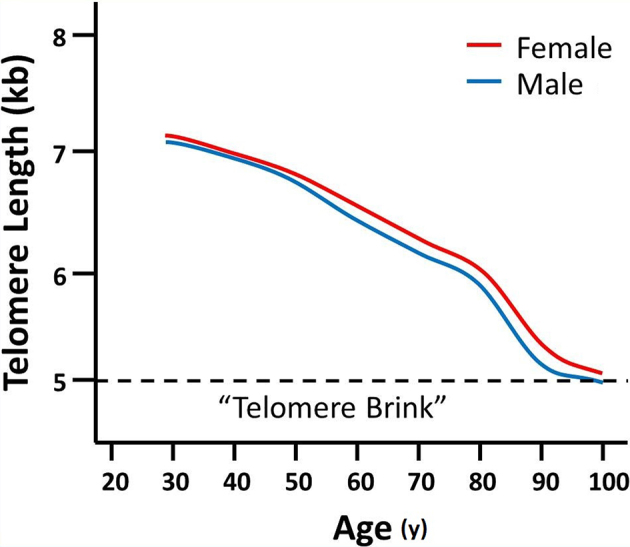

The relationship between age and telomere length has been established in a large, very healthy cohort, with a precise telomere threshold length called the “brink” associated with cell death.28 As shown in Figure 10, these very healthy people did not approach the critical 5-kb telomere length until they were in their 90s. The telomere “brink” is approached at any age when a person experiences disease, injury, and reduced activity.

Figure 10.

Simplified adaptation of data from a recent report28 that established leukocyte telomere length in a large cohort of healthy men and women of various ages. The authors identified a “telomere brink,” a telomere length threshold below which the probability of survival substantially declined. Although not shown on this simplified plot, it is important to note that due to natural variation, telomere length varies widely among individuals of the same age.

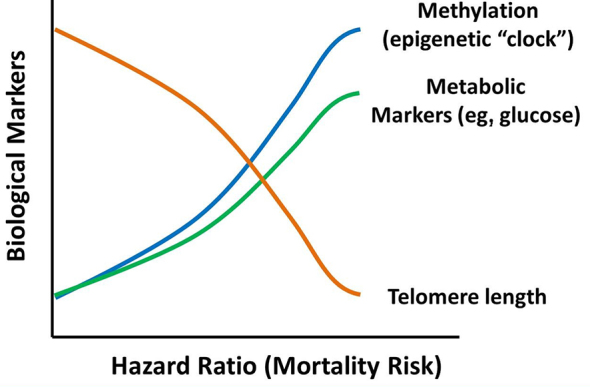

So, if the dose of activity that we prescribe for our patients promotes the PGC1 alpha gene and subsequently preserves telomere length, reduces methylation, and reduces blood glucose levels, then we should be optimizing the potential to decrease the mortality risk for people with compromised movement (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Conceptual relationship between mortality risk and various biomarkers of metabolic health: gene methylation, systemic metabolic markers, and telomere length. Optimally dosed movement interventions can reduce mortality risk by improving one or all of these metabolic biomarkers.

Within my own laboratory, we recently demonstrated that a certain dose of skeletal muscle activity that up-regulates PGC1 alpha also up-regulates pathways associated with telomere function in humans with paralysis (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Preliminary data from our laboratory indicate that after spinal cord injury, the strong up-regulation of PGC1 alpha observed with an appropriately-dosed movement intervention is associated with up-regulation of gene pathways associated with telomere function. (See Fig. 8 for gene array interpretation information.) RNA = ribonucleic acid, DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid.

Human activity and epigenetics is in its infancy. A recent PubMed search revealed that there were fewer than 100 peer-reviewed publications related to physical activity in 1950; in 2015, there were over 40,000 papers. There were fewer than 100 publications related to epigenetics in the year 2000; in 2015, there were over 10,000 papers. When we combine a search for physical activity and epigenetics, there are fewer than 200 published papers.

I believe that our understanding of how movement affects the epigenome is much like where we were with exercise in 1950. I believe that we are witnessing the beginning of the new frontier in epigenomic physical therapy.

“The Human Experience”

I began this discussion by suggesting that the future of our profession lies at 2 extremes: the micro-scale frontier of epigenomic physical therapy, and the macro-scale frontier of the “human experience.” When I hear the words “human experience.” one patient immediately comes to mind. Mr. P was a 22-year-old man whom I met at our medical center in 1981. He had a thoracic level spinal cord injury in 1975 at the age of 18. The immobility from his paralysis caused an accelerated aging of his tissues.

We have published extensively about accelerated aging and bone deterioration after this injury.29-31 In addition to severe bone mineral loss, Mr. P lost his major endocrine organ, skeletal muscle, through atrophy; and, as expected, he developed metabolic disease. These secondary complications led to fractures and skin ulcers that would not heal.

In 1988, to save his life, Mr. P received a rare surgery, a hemicorporectomy; an amputation at the level of his lumbar spine.32 (Fig. 13).

Figure 13.

Mr. P after hemicorporectomy (left) and after receiving a socket prosthesis and manual wheelchair (right). Reprinted with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association from Shields RK, S Dudley-Javoroski. Musculoskeletal deterioration and hemicorporectomy after spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 2003;83:263–275.

I will never forget his words after the surgery, which he recorded in his journal: “I cannot see the end of my body. My arm reaches out at an expanse of white—my mind is blank. There are no words to describe the loss. I drop the covers and my head in tears. My physical self is no longer the problem…”. Clearly, Mr P’s human experience was profoundly negative.

Mr. P signifies a case in which physical therapy did not “turn over the hourglass” and extend the life of his tissues; rather, we accelerated cellular death by not teaching him how to move correctly away from the deleterious forces that scarred his skin and fractured his weakened bones.

His care program focused on walking, an activity that was more “institution-centered” than “patient-centered.” My dear colleagues, beware of the treatments that are more about the therapist or the technology than about the patient.

We are in an era where sensationalistic treatments, often involving unproven technologies, grab the attention of the media and the research world for nice soundbites—but often at the cost of teaching a skill that can be used for a lifetime. Even teaching a patient to wheel a chair has health implications if carried out over 30 years.

As treatment times are being cut in bundled health care payment models,33 we must prioritize our treatments that are needed in the precious time available, and articulate those to the naive patient. What the patient wishes for or desires is not always what they need, and it is our professional responsibility to redirect those expectations.

Do not be fooled by the extreme condition of Mr. P. If you examine your patients closely, tissue deterioration from lack of mobility and exercise is pervasive—especially in the orthopedic outpatient population. People seek our services with the expectation that they will learn something new that sets them on a path to improved health. This is the human experience.

How many of our patients, like Mr. P, do not have their expectations met or at least refocused after an episode of care with a physical therapist?

Expectations of Our Patients

Let me illustrate some of the nuances of patient expectation and how it affects the human experience. How many of you called or sent letters of appreciation to your airline when you arrived safely in Boston this week? How many of you would have preferred, or wished, that you arrived in Boston 45 minutes early? How many of you expected to arrive in Boston on time? How many of you would have viewed the flight a success if you arrived safely, even if delayed a few hours? How many of you would have deemed the flight a failure if you had been carried off the plane because they needed your seat?

As you can see, there is a difference between what you wish for, what you expect, and what you would view as a successful experience when you fly. I believe our patients have the same types of expectations that need to be understood at the start of each episode of care.

If we aspire to enhance the patient experience, we must measure it34,35—and, in addition, we must know how many visits it takes to achieve the patient's experience. We need an “Experience-Efficiency Index” that is feasible and easily administered, considers the 3 levels of patients’ expectations, yields meaningful information about the human experience, and has relevance to all health care sectors.

Much like the visionaries of the Framingham studies, we should plant the seed today to develop a longitudinal data set that can be used to gauge our overall success in affecting the human experience.

Who would be the major stakeholders for a data set that captures the patient's experience? Our professional organization, APTA, would have at their fingertips the percentage of patients who receive what they wish for, what they expect, and what they would view as a successful outcome after an episode of care with a physical therapist.

Clinical practices would understand how therapists perform, with the goal of reducing the number of unmet expectations each year. They would gain clarity about the number of treatments associated with each tier of patient expectation. Adjustments in case-mix would enable benchmarking across comparable clinical practices and provide a metric needed for bundled care models.

Academic physical therapy programs would require that students report the percentage of their patients that had unmet expectations, fostering reflection on those cases. For all students in a class, the entire academic institution would possess an average experience-efficiency index representing their clinical outcome signature, to complement the process-based signature that is currently captured in the Clinical Performance Instrument [CPI].

CAPTE [Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education], the academic accrediting body, would expect to review academic departments’ experience-efficiency indexes at the time of accreditation and review the policies of how institutions manage patterns of unsuccessful clinical education outcomes.

Residency training and specialization programs, in collaboration with clinical practices, could readily determine if practitioners with residency and/or specialty training have fewer negative patient experiences and greater experience-efficiency indexes as compared with those without training.

Multiple regional centers that adopt this metric could collaborate to funnel all data into a central, open-sourced repository.

When we developed the first physical therapy electronic medical record and database in 199136 with support from the Foundation for Physical Therapy, our pilot data supported that this type of measurement was feasible and psychometrically sound and could be reasonably implemented as a standard.

I believe the Patient Centered Outcomes Questionnaire [PCOQ],35,37 with modifications, is an excellent universal measurement to capture the human experience in physical therapist practice.

Importantly, a common outcome measurement tool for all sections, residency programs, clinical practices, academic programs, and accreditation services will foster tighter coordination among the stakeholders that need to work together as one.

Our Future Colleagues: The Students

As alluded to in the beginning of this lecture, the “human experience” encompasses the perspective of another very important group of stakeholders; our future colleagues, the students.

Our future colleagues and current students are critical to our future. If they incur excessive debt that they cannot recover from, we will suffer the consequences as a profession.38 The first step to addressing the student debt crisis is to openly measure the debt and have it publicly available.

Since 1978, the Association of American Medical Colleges—the AAMC—has invited graduating medical students to rate the quality of their education via the Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). The GQ focuses on 4 areas: 1) student debt, 2) curricular quality, 3) adequacy of programs and environment, and 4) student mistreatment. Data from all medical education programs in the United States are made publicly available in aggregate form. Each medical school, at the time of accreditation, must report their scores relative to all other medical schools from across the country.

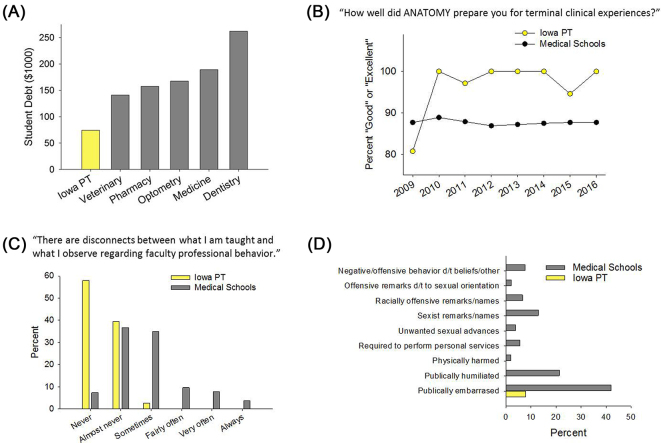

In 2009, we adopted the AAMC survey, with subtle modifications, so that we could benchmark our education outcomes relative to all medical schools or other doctoring professions, if available, across the country. For example, we examined our Iowa students’ education debt as compared to dentistry,39 optometry,40 pharmacy,41 medicine,42 and veterinary medicine43 (Fig. 14A). The one profession to which we cannot benchmark is physical therapy. This needs to change.

Figure 14.

Selected measurements from the University of Iowa Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science annual benchmarking analysis. (A) Debt reported by Iowa graduating physical therapy students, compared with debt reported to the professional organizations of other health professions (see text for references). (B-D) The Department administers a slightly modified version of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Graduation Questionnaire, then benchmarks to the mean of all medical education programs nationwide. (B) Physical therapist versus medical student ratings of anatomy curriculum. (C) Physical therapist versus medical student perceptions of faculty professionalism. (D) Physical therapist versus medical student reports of student mistreatment. Iowa PT = University of Iowa Department of Physical Therapy, d/t = due to.

At the curriculum level, we could determine the percentage of our students who viewed courses like anatomy as valuable preparation for their terminal clinical experiences, as compared with all medical students44 (Fig. 14B). We could not benchmark our curriculum to our peer academic physical therapy departments.

At the environment level, we could determine the percentage of our students, as compared with medical students, who report that there are “never” or “almost never” disconnects between what they are taught about professional behaviors and what they observe among our faculty44 (Fig. 14C). This provides insights about a program's hidden curriculum.45 Again, while we could benchmark to medicine,44 but we cannot benchmark to our peer academic physical therapy departments.

We also gained reassuring confirmation that our students do not experience the high rates of verbal mistreatment—and the worrying rates of racism, sexual misconduct, and assault—that are prevalent in health care education programs44,46 (Fig. 14D). We believe that all programs must ask systematic questions regarding uncomfortable but historically prevalent aspects of health care education before accreditation is ever granted.

Though I have shared only 4 examples from our rich data set, the value of annual and thorough benchmarking can assist in understanding an academic program's relative position within the constellation of health care education.

APTA and ACAPT are making strides in developing a method to benchmark peer institutions within academic physical therapy. As this important process moves forward, the AAMC is an excellent organization to model because they govern these important survey materials with a full staff of scientists and psychometricians who have expertise in measurement and who are independent from the academic programs being surveyed. I strongly recommend that we avoid the business of governing our own benchmarks through physical therapy program directors as members of ACAPT.

Likewise, we should work to have physical therapy research funding included in the Blue Ridge Institute of Medical Research database along with pharmacy, nursing, medicine, veterinary medicine, public health, and dentistry. Through the National Advisory Board for Rehabilitation Research, we are working with NIH to tag grant submissions from physical therapists to facilitate the independent capture of the departments, institutions, and scientists who are principal investigators and leaders in federally funded rehabilitation research.

Summary: The Frontiers of Physical Therapy

As we move toward the conclusion of this lecture, you may feel we have traveled a long way. We’ve journeyed from epigenetics, the most micro-scale foundation of our profession, to the concept of the human experience, the broadest, most macro-scale endpoint of our endeavors as clinicians and educators. This isn’t by coincidence. For much of our profession's history, we’ve inhabited the region between these 2 extremes. But the frontiers of our profession lie at the extremes. Those are the places we must travel if we wish to truly “transform society by optimizing movement.”

With each generation, physical therapists have identified scientific frontiers that enable us to more skillfully diagnose and treat movement dysfunction. Today's scientific discoveries will equip us to advance human performance more effectively than at any other time in our history. With sufficient will and cooperation, we can use simple, powerful tools that are now at our disposal, to measure our effectiveness and hone our craft.

The idea of a central outcome measure of patient experience, one that has meaning to all stakeholders in our profession, is necessary for our future, as growth can create silos that emphasize differences rather than our commonalities.

We must be disciplined as we strive to infuse new knowledge in the classroom and capture the patient experience in the clinic—without adding courses, credit hours, debt, or altering clinical productivity. This can be done by weeding out the old and embracing the new with the same vigor that Mary McMillan portrayed throughout her career.

By this rejuvenation of our profession, we can turn over the hourglass with a new timeline and shared vision to optimize movement and transform every patient's human experience.

I thank you for your attention and for the honor to present the 48th Mary McMillan Lecture.

Acknowledgments

Dr Shields thanks the faculty and staff at the University of Iowa Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science for their rich discussions that formed the basis for this lecture. Shauna Dudley-Javoroski, PT, PhD, provided invaluable assistance with data analysis and manuscript review. Allyson Merfeld assisted with the development of graphic illustrations. Finally, Dr Shields is grateful to the following individuals who wrote letters of support for his nomination: Rebecca Craik, Anthony Delitto, Edelle Field-Fote, Alan Jette, Charles Magistro, Daniel Riddle, and R. Scott Ward.

The 48th Mary McMillan Lecture was presented at NEXT: Conference & Exposition of the American Physical Therapy Association; June 22, 2016; Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1. Collier W. Athletic exercises as a cause of disease of the heart and aorta. Transactions of the Medical Society of London. 1893;16:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pedersen BK. Muscles and their myokines. J Exp Biol. 2011;214(Pt 2):337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schnyder S, Handschin C. Skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ: PGC-1alpha, myokines and exercise. Bone. 2015;80:115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wrann CD, White JP, Salogiannnis J et al. Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1alpha/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metab. 2013;18(5):649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krebs HA, Johnson WA. The role of citric acid in intermediate metabolism in animal tissues. Enzymologia. 1937;4:148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krebs HA. The history of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Perspect Biol Med. 1970;14(1):154–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watson JD, Crick FHC. A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilkins MHF, Stokes AR, Wilson HR. Molecular structure of deoxypentose nucleic acids. Nature. 1953;171:738–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Franklin R, Gosling RG. Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate. Nature. 1953;171:740–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Physical Therapy Association Vision Statement for the Physical Therapy Profession. http://www.apta.org/Vision/. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 11. Marciello MA, Herbison GJ, Cohen ME, Schmidt R. Elbow extension using anterior deltoids and upper pectorals in spinal cord-injured subjects. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1995;76(5):426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shavelle RM, DeVivo MJ, Brooks JC, Strauss DJ, Paculdo DR. Improvements in long-term survival after spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(4):645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeVivo MJ. Sir Ludwig Guttmann Lecture: trends in spinal cord injury rehabilitation outcomes from model systems in the United States: 1973-2006. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(11):713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hastings J, Robins H, Griffiths Y, Hamilton C. The differences in self-esteem, function, and participation between adults with low cervical motor tetraplegia who use power or manual wheelchairs. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(11):1785–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gabriel BM, Zierath JR. The limits of exercise physiology: from performance to health. Cell Metab. 2017;25(5):1000–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toigo M, Boutellier U. New fundamental resistance exercise determinants of molecular and cellular muscle adaptations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;97(6):643–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program. https://allofus.nih.gov/. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 18. Framingham Heart Study https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 19. United States Department of Homeland Security Energy Sector-Specific Plan. Washington, DC: US Department of Homeland Security; 2015. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/nipp-ssp-energy-2015-508.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davison JE, Rahman S. Recognition, investigation and management of mitochondrial disease. Arch Dis Child. 2017. http://adc.bmj.com/content/archdischild/early/2017/06/24/archdischild-2016-311370.full.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adams CM, Suneja M, Dudley-Javoroski S, Shields RK. Altered mRNA expression after long-term soleus electrical stimulation training in humans with paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(1):65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Little JP, Safdar A, Bishop D, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. An acute bout of high-intensity interval training increases the nuclear abundance of PGC-1{alpha} and activates mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(6):R1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hernandez-Alvarez MI, Thabit H, Burns N et al. Subjects with early-onset type 2 diabetes show defective activation of the skeletal muscle PGC-1{alpha}/Mitofusin-2 regulatory pathway in response to physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):645–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weinhold B. Epigenetics: the science of change. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(3):A160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Christiansen L, Lenart A, Tan Q et al. DNA methylation age is associated with mortality in a longitudinal Danish twin study. Aging Cell. 2016;15(1):149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diman A, Boros J, Poulain F et al. Nuclear respiratory factor 1 and endurance exercise promote human telomere transcription. Sci Adv. 2016;2(7):e1600031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steenstrup T, Kark JD, Verhulst S et al. Telomeres and the natural lifespan limit in humans. Aging. 2017;9(4):1130–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dudley-Javoroski S, Shields RK. Muscle and bone plasticity after spinal cord injury: Review of adaptations to disuse and to electrical muscle stimulation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(2):283–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dudley-Javoroski S, Shields RK. Longitudinal changes in femur bone mineral density after spinal cord injury: effects of slice placement and peel method. Osteoporosis Int. 2009;21(6):985–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dudley-Javoroski S, Shields RK. Regional cortical and trabecular bone loss after spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(9):1365–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shields RK, Dudley-Javoroski S. Musculoskeletal deterioration and hemicorporectomy after spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 2003;83(3):263–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moore JD. Unpacking Payment Bundles. Phys Ther. 2016;96(2):139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Cleland JA. Individual expectation: an overlooked, but pertinent, factor in the treatment of individuals experiencing musculoskeletal pain. Phys Ther. 2010;90(9):1345–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zeppieri G Jr., George SZ. Patient-defined desired outcome, success criteria, and expectation in outpatient physical therapy: a longitudinal assessment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shields RK, Leo KC, Miller B, Dostal WF, Barr R. An acute care physical therapy clinical practice database for outcomes research. Phys Ther. 1994;74(5):463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robinson ME, Brown JL, George SZ et al. Multidimensional success criteria and expectations for treatment of chronic pain: the patient perspective. Pain Med. 2005;6(5):336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jette DU. Physical Therapist Student Loan Debt. Phys Ther. 2016;96(11):1685–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wanchek T, Cook BJ, Valachovic RW. Annual ADEA Survey of Dental School Seniors: 2016 Graduating Class. J Dent Ed. 2017;81(5):613–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry Annual Student Data Report, Academic Year 2016–2017. Rockville, MD: Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry; 2017. https://www.optometriceducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ASCO-Student-Data-Report-2016-17-updated-June-2017-2.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 41. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Graduating Student Survey 2016 National Summary Report. Alexandria, VA: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 2016. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Pages/GraduatingStudentSurvey.aspx. Accessed June 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Association of American Medical Colleges Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs and Loan Repayment Fact Card 2016. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43. American Veterinary Medical Association Report on Veterinary Markets. Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association; 2016. http://atwork.avma.org/2016/03/15/avma-releases-2016-report-on-veterinary-markets/. Accessed June 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Association of American Medical Colleges All Schools Reports. https://www.aamc.org/data/gq/allschoolsreports/. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 45. Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, eds. The Hidden Curriculum in Health Professional Education. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, Rappley MD. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(5):705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]