Abstract

Background

Individuals with HIV, especially those on antiretroviral therapy (ART), may have increased risk of hypertension. We investigated the prevalence of hypertension at enrolment and 12 months after commencing ART in a Nigerian HIV clinic.

Methods

Data from patients enrolled for ART from 2011 to 2013 were analysed, including 2310 patients at enrolment and 1524 re-evaluated after 12 months of ART. The presence of hypertension, demographic, clinical and biochemical data were retrieved from standardized databases. Bivariate and logistic regressions were used to identify baseline risk factors for hypertension.

Results

Prevalence of hypertension at enrolment was 19.3% (95% CI 17.6–20.9%), and age (p<0.001), male sex (p=0.004) and body mass index (BMI) (p<0.001) were independent risk factors for hypertension. Twelve months after initiating ART, a further 31% (95% CI 17.6–20.9%) had developed hypertension. Total prevalence at that point was 50.2%. Hypertension among those on ART was associated with age (p=0.009) and BMI (p=0.008), but not with sex. There were no independently significant associations between hypertension and CD4+ counts, viral load or type of ART.

Conclusions

Hypertension is common in HIV infected individuals attending the HIV clinic. Patients initiating ART have a high risk of developing hypertension in the first year of ART. Since BMI is modifiable, life-style advice aimed at weight reduction is strongly advisable.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, Antiretrovirals, HIV/AIDS, Hypertension, Nigeria

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) accounted for about half of the 39.5 million deaths caused by non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in 2015 globally and were responsible for nearly 40% of the million deaths attributed to NCDs in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Hypertension is a major risk factor for death due to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and renal disorders, and is responsible for about 58% of deaths caused by CVD world-wide.2 The prevalence of hypertension is projected to rise from 26% in 2010 to 29% by 2025, affecting 1.56 billion people in the developing countries, where HIV/AIDS is also a major public health problem.3 In Africa, the prevalence of hypertension increased from about 20 to 31% within a decade,4 and this increase is widely attributed to a demographic transition and the adoption of western lifestyles. A national hypertension survey using a blood pressure threshold of 160/100 mmHg reported a prevalence of 11% in Nigeria,5 individual studies using a threshold of 140/90 mmHg have reported prevalence between 14.5 and 50.5%.6,7 Nigeria is the most populous African country with an estimated 170 million population, and with about 3.4 million people living with HIV (PLWH), has the second highest burden of HIV/AIDS in the world.7

Lifestyle and biological clustering of risk factors for NCDs such as smoking, unfavourable lipid profile and glucose metabolism and endothelial dysfunction are more frequently seen among PLWH than in HIV-negative individuals,8–10 and PLWH have a higher prevalence of CVD and other NCDs than non-infected individuals. Although hypertension is only one of the factors that confer risk for CVD, it is a relatively common sign which is easy to diagnose, and it is usually amenable to preventive and therapeutic interventions that reduce morbidity and mortality.11

Hypertension is often observed among individuals on anti-retroviral therapy (ART), and is attributed to increased body weight, male sex and increasing age.12–14 However, associations between markers of progression of HIV infection such as viral load, duration of infection and nadir CD4+ count have also been associated with CVD.15,16

Whereas there is published literature on the prevalence of hypertension and the risk of CVD among PLWH in sub-Saharan Africa,17,18 estimates from large studies are difficult to find in West Africa. In the present study, we determined the prevalence, incidence and correlates of hypertension in treatment naïve PLWH and at 12 months of ART initiation in a large Nigerian cohort.

Methods

This was a mixed study design consisting of a cross sectional survey at baseline and a retrospective component at 12 months of ART involving all newly registered patients attending the AIDS Prevention Initiative of Nigeria (APIN) adult ART clinic of Jos University Teaching Hospital. The APIN clinic is a regional referral centre providing comprehensive HIV/AIDS services for Plateau State, with a population of about 3 million. Following registration at the clinic, all patients are offered lifestyle advice, clinical evaluation and laboratory investigations for the assessment of ART eligibility. Eligibility for ART was according to the 2010 National treatment guidelines19; briefly, a CD4+ ≤350 cells/μl and/or the presence of an AIDS defining illness. Once enrolled, patients are followed 2-weekly, monthly, quarterly and 6-monthly depending on whether they have symptoms or have initiated ART. Socio-demographic, clinical and laboratory information is entered into standardized forms and uploaded onto a single electronic database developed in FileMaker Pro version 10 (Filemaker, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) in dedicated computers to ensure data consistency and completeness. The database is cleaned and curated by trained data management staff. Data errors for this study were further corrected by checking the original patient case notes and the electronic databases.

Data on all patients ≥18 years old who had qualified for ART from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2013 were retrieved from the database to review their characteristics at the time of initial registration. Patients without baseline blood pressure records and those who had initiated ART at the time of enrolment into the service were excluded from the analysis of baseline hypertension.

Data retrieved included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol (mmol/l), CD4+ cell counts (per μl) and HIV viral load (copies/ml) on enrolment, and ART regimen. The most frequently prescribed first line regimens were: lamivudine+zidovudine+nevirapine (59%), and lamivudine or emtricitabine+ tenofovir+efavirenz (41%). The most frequent second line regimens were atazanavir/ritonavir (92%) and lopinavir/ritonavir (8%). Blood pressure (BP) was measured on enrolment and at 12 months with a digital sphygmomanometer (Omron M4-I, Churchill, Oxon, UK, 2005; accuracy ±3%) using appropriate cuffs on the left arm with the patient sitting. Measurements in those with elevated BP were repeated using a manual mercury sphygmomanometer (Accoson, Harlow, Essex, UK) after about 5 minutes of rest and the second measurement was recorded. The same methods were used to assess BP during enrolment and at 12 months of ART. Hypertension was defined as a systolic BP ≥140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood BP ≥90 mmHg or self-reported pharmacological treatment for hypertension.20 It is standard practice in our facility for the consulting clinician to interview patients with self-reported use of anti-hypertensives in order to determine the appropriateness of the diagnosis of hypertension. Hypercholesterolemia was defined according to the USA National Cholesterol Education Programme21 while estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was derived by the Cockcrof-Gault formula.22

The main outcome measures were the prevalence of hypertension on enrolment, the cumulative incidence of hypertension within a year of initiating ART and the association of hypertension with traditional and HIV-related risk factors. The precision for the estimates of hypertension based on 2310 patients eligible for the study was ±2% at 95% confidence level, based on an assumed hypertension prevalence of 25%. Okeahialam et al. had reported a prevalence of 21% in a rural community outside Jos in 2012.23

The identity of all patients was anonymized across the data set by replacing their names with serial numbers.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 2011(Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as means±SD, or medians with ranges. Categorical variables were presented as proportions and compared using χ2 tests. Means were compared using paired or unpaired Student's t tests, as appropriate. Positively skewed data were log10 transformed. Bivariate analysis was conducted and variables with p<0.25 were entered into multiple logistic regression models. Results of the bivariate analyses and logistic regressions were presented as OR and adjusted OR (AOR), with 95% CI, respectively. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

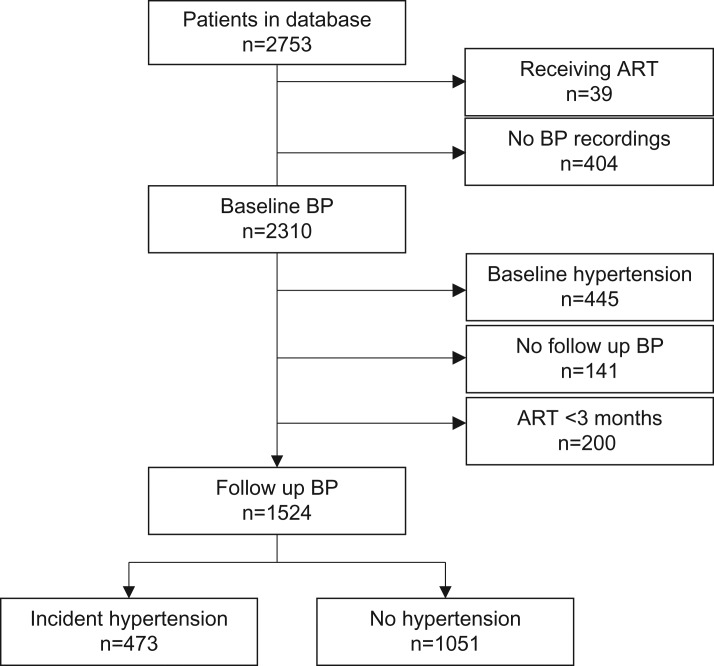

There were 2753 patients in the database within the study period, out of which 2310 (83.9%) were eligible for analysis of baseline hypertension and 1524 (55.4%) for newly developed hypertension within the first year of ART. The patient selection process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection from 2011 to 2013 at the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. ART: antiretroviral therapy; BP: blood pressure.

At baseline, 445 (19.3%; 95% CI 17.6–20.9%) of 2310 patients had hypertension of which 248 (55.7%) were unaware they were hypertensive. Only five (2.5%) individuals with hypertension self-reported use of anti-hypertensives. Increasing age, male sex, BMI, CD4+ counts and viral load were associated with hypertension in the bivariate analysis. However, only the first three factors were statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. For every 1 year increase in age, the risk of hypertension increased by 4% (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.06); males were 63% more likely to have hypertension than females (AOR 1.63, 95% CI 1.17–2.28) and 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI increased the risk of hypertension by 14% (AOR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.18). There were no significant associations with cholesterol and eGFR. The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with and without hypertension at baseline in a cohort of people living with HIV from 20011 to 2013 at the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

| Characteristics | n (%) | Hypertension n (%) | No hypertension n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | 2310 (100%) | 445 (19.3%) | 1865 (80.7%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean age (SD) years | 2300 (99.6%) | 41.0 (10.0) | 36.8 (9.8) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.001 |

| Male:Female (male%) | 2310 (100%) | 208:237 (46.7%) | 654:1211 (35.1%) | 1.62 (1.32–2.02) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.17–2.00) | 0.004 |

| Mean BMI (SD) Kg/m2 | 2073 (89.3%) | 24.4 (4.6) | 21.3 (4.4) | 1.12 (1.11–1.15) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.11–1.18) | <0.001 |

| Mean cholesterol (SD) mmol/L | 2106 (91.2%) | 4.6 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.4) | 0.78 (0.57–1.06) | NS | 0.63 (0.40–1.00) | NS |

| Median CD4+ (range)/mm3 | 2215 (95.9%) | 233 (5–1161) | 166 (2–1387) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.08–1.02) | NS |

| Log10 mean viral load (SD) copies/ml | 1432 (62%) | 4.5 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.1) | 0.85 (0.76–0.94) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.82–1.02) | NS |

| Mean eGFR (SD) mls/min | 1949 (84.4%) | 81.3 (30.0) | 79.6 (27.3) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | NS | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | NS |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; BMI: body mass index; CD: cluster of differentiation; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; NA: not applicable; NS: not significant.

Hosmer and Lemeshow test: χ2=1.274; p-value=0.996.

Of the 1524 individuals without hypertension at baseline, 473 (31.0%; 95% CI 28.7–33.4%) developed hypertension at one year of commencing ART. In the bivariate analysis, those who developed hypertension were older (p<0.001) and had higher BMI (p<0.001) than those who remained normotensive. There were no significant differences in sex, cholesterol levels, CD4+ counts, viral load, eGFR and ART regimen between those with and without hypertension. For unit increase in continuous variables, only age (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.07, p=0.009) and BMI (AOR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.18, p=0.008) were independently associated with hypertension as shown in Table 2. When baseline plus newly acquired hypertension were considered together, hypertension was present in 918 (50.3%) of the study cohort.

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis of factors incident hypertension in a cohort of people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy from 2011 to 2013 at the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

| Characteristics | n (%) | Hypertension n (%) | No hypertension n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | 1524 (100) | 473 (31.0) | 1051 (69.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean age (SD) years | 1516 (99.5) | 38.6 (9.8) | 36.3 (9.0) | 1.11 (1.02–1.19) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.009 |

| Male:Female (male %)a | 1524 (100) | 175:298 (40.0) | 396:682 (35.1) | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | NS | NA | NA |

| Mean BMI (SD) Kg/m2 | 1372 (90.0) | 22.3 (4.6) | 21.3 (4.3) | 1.17 (1.13–1.22) | <0.001 | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 0.008 |

| Mean Cholesterol (SD) mmol/L | 1386 (91.0) | 4.0 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.7) | 1.03 (0.97–1.04) | NS | 0.95 (0.88–1.31) | NS |

| Median CD4+ (range)/mm3 | 1458 (96.0) | 172 (3–1387) | 157 (4–1236) | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | NS | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | NS |

| Log10Mean viral load (SD) copies/mla | 1158 (76.0) | 4.6 (1.2) | 4.7 (1.1) | 1.23 (0.68–1.97) | NS | NA | NA |

| Mean eGFR (SD) mls/min | 1272 (83.5) | 79.7 (27.5) | 81.8 (31.7) | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) | NS | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | NS |

| 1st:2nd line ART (1st line %)a | 1502 (98.5) | 458:13 (97.2) | 1008:23 (97.8) | 1.08 (0.84–1.38) | NS | NA | NA |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; BMI: body mass index; CD: cluster of differentiation; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; NA: not applicable; NS: not significant.

a p>0.25 in univariate analysis. Hosmer and Lemeshow test: χ2=1.274; p=0.996.

Missing data analysis

In most cases, less than 10% of data for variables of interest were missing at baseline except for log10 mean viral load (38%) and eGFR (15.6%). These were analysed and compared as separate categories, with results showing absence of statistically significant difference by age (p=0.436), sex (p=0.112), BMI (p=0.712) and median CD4+ count (p=0.538). Similarly, missing data for log10 mean viral load (24%) and eGFR (16.5%) were observed with no difference by age (p-value=0.301), sex (p=0.623), BMI (p=0.574) and median CD4+ count (p=0.455) at 12 months.

Discussion

In this large cohort of HIV-positive Nigerians, the prevalence of hypertension was 19.3% at the time of enrolment into the clinic. Hypertension on enrolment was associated with older age, being male and having a higher BMI. There was no association with eGFR, cholesterol level and HIV-related factors. After initiation of ART, a further 473 (31.0%) patients developed hypertension. In this group, hypertension was associated with increasing age and BMI. BMI was the strongest predictor of hypertension at enrolment and after 12 months of ART. The combined prevalence at enrolment and incidence following ART initiation was therefore 50.3%.

The 19% prevalence at enrolment is the same as reported in western Nigeria24 and the 22% reported in in the US among ART naïve patients.25 A similar prevalence was also reported from a rural population outside Jos that was not screened for HIV infection, suggesting the prevalence of hypertension in the whole population is likely to be high.23 However these estimates are higher than the 2% prevalence in ART-naïve adults in north west Nigeria.26 Conversely, our prevalence at enrolment is lower than the 26% reported in a Brazilian study.27

Data on hypertension over extended periods of observation among Nigerian HIV-infected cohorts is scant. A study of 241 patients in the north east reported that 37% had become hypertensive in a two year study.28 The 31% incidence found at 12 months of ART in the current study is however similar to 28% reported in a study of 5563 patients in Uganda.18 The incidence in our treated patients is much higher than 17% among ART-experienced patients reported in north west Nigeria,26 and the 8% in a multi-national data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs (D:A:D Study) involving more than 20 000 patients in industrialized countries,8 where population prevalence are similar to those in Nigeria29,30 Conversely, a prospective study involving 1465 individuals attending integrated HIV/NCDs clinics in Kibera, Kenya, found hypertension in 87%, even though the community prevalence was 29%.31,32 However, the clinics in Kibera also attend to non-infected patients and the study did not state the proportion of HIV-infected individuals who were hypertensive. Most differences in hypertension rates may be explained by variations in study methodologies, sample size and patient characteristics. For example, Friis-Moller et al.8 defined hypertension as BP ≥150/100 (vs ≥140/90 in this study), and the mean age in the cohort from north east Nigeria28 was 46 years compared to 37 years in this study.

The associations between hypertension and age, male sex and BMI in HIV-infected patients have been previously reported in Barcelona33 and Brazil.27 Although we found these associations, the association with sex disappeared after 12 months of ART. The higher proportion of males (70% vs 40%) and the higher mean BMI (25.7 kg/m2 vs 22.4 kg/m2) in Barcelona might account for these differences. At enrolment, the mean cholesterol levels were higher in the hypertensive group, though this difference did not quite reach significance (p=0.052), and was in keeping with the study in north eastern Nigeria.28 Although we did not measure triglycerides, the Brazilian study reported an independent association with triglycerides rather than with total cholesterol.27

We were unable to measure dietary habits, physical activity, lipid fractions, presence or pattern of lipo-accumulation, smoking and alcohol use. Among the factors measured, there was also no association between hypertension and HIV-related factors, though the CD4+ count and viral load were significant at the univariate analyses (p<0.001) and the CD4+ count was close to significance at multivariate (p=0.062) at the time of enrolment. This is in agreement with a longitudinal study of over 17 000 patients in another DAD study which reported a significant association with viral suppression, but not with CD4+ count.14 Nonetheless, it is thought that improved well-being brought about by ART, which frequently includes weight gain, CD4+ recovery and viral suppression may be responsible for the development of hypertension.13

Gazzaruso et al.34 reported an independent association between hypertension and the metabolic changes induced by ART following exposure to protease inhibitors for 31 months and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors for 80 months, but that there was no significant association with the ART regimen used. Baekken et al.35 in contrast reported an independent association between ART and hypertension in a cohort where about 70% of ART was based on protease inhibitor-regimens, with the most effect in patients exposed for >5 years. The lack of association between the ART regimen and hypertension in this study is likely due to only 4% of ART prescription being based on protease inhibitor and that patients had received ART for only one year.

Although our study is a large observational cohort in West Africa and one of the largest in sub-Saharan Africa, it has several limitations. As a retrospective study, some uncertain patient outcomes and missing data, mostly involving eGFR and viral load, might have introduced bias. We had to rely on routine blood pressure measurements that were not ideally standardized, and might have over-estimated hypertension due to a ‘white coat’ effect in which patients in a clinical setting exhibit a blood pressure level above the normal range, which is likely to be most prominent at the time of being diagnosed with a life-long infection. Nonetheless, this is a reflection of ‘real-life’ clinical practice and in any case, white coat hypertension is known to predict the development of sustained hypertension.36 Whilst not commonly available in developing countries, ambulatory blood pressure measurement may have been useful in distinguishing individuals with ‘white coat’ hypertension from those with sustained hypertension. Also, relevant risk factors of hypertension such as smoking, family history and anthropometric measurements were not routinely collected. This is probably a reflection of the greater emphasis placed on HIV disease alone, but which should now expand to cover the increasingly important NCDs. Lastly, the 12 months exposure to ART was a relatively short period to demonstrate a significant relationship between hypertension and ART regimens.

Conclusions

In conclusion, hypertension is common among HIV/AIDS patients initiated on ART. It is associated with both non-modifiable factors such as age and modifiable factors such as BMI, which conferred the strongest risk. A 50.3% total prevalence of hypertension may be indicative of a substantial burden in terms of treatment cost and a high risk for the occurrence of vascular events. Consequently, supporting patients to achieve healthy dietary and lifestyle behaviour is paramount for the prevention of NCDs in PLWH. While the relationship between hypertension and ART requires further long term exploration, patients with HIV initiating ART need to be aware of the risk of developing hypertension and HIV treatment programs should integrate services for NCDs such as hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Authors' contributions: Professors Cuevas and Gill are joint senior authors. CJ and HGM conceived the study; BJA and CJ designed the study protocol; BJA and HGM carried out the clinical assessment; CJ and FT carried out the immunoassays and cytokine determination, and analysis and interpretation of these data. BJA and CJ drafted the manuscript; BJA HGM and FT critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. BJA and CJ are guarantors of the paper.

Acknowledgements: This study represents work from Dr Isa's MSc dissertation at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. We acknowledge Dr Ralf Weigel who was the Director of Studies for the course. We also wish to thank PEPFAR Harvard and the AIDS Prevention Initiative of Nigeria for permitting the use of data presented in this study.

Funding: This work was funded in part by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (U51HA02522) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through a cooperative agreement with APIN (PS001058); by the Government of Nigeria through the Tertiary Education Trust Fund and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine by providing partial study scholarships to SIE and the Medical Education Partnership Initiative in Nigeria (MEPIN) project funded by Fogarty International Center, the Office of AIDS Research, the National HumanGenome Research Institute of the National Institute of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator under Award Number R24TW008878. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the funding institutions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the Jos University Teaching Hospital Ethics committees.

References

- 1. Mensah GA, Roth GA, Sampson UK et al. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Cardiovasc J Afr 2015;26(2 Suppl 1):S6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adeloye D, Basquill C. Estimating the prevalence and awareness rates of hypertension in Africa: a systematic analysis. PloS ONE. 2014;9:e104300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akinkugbe OO. Expert committee on non-communicable diseases in Nigeria. Final Report of a National Survey. Ministry of Health and Social Services Lagos, Nigeria: 1997, p. 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S et al. The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of west African origin. Am J Public Health 1997;87:160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amole IO, OlaOlorun AD, Odeigah LO, Adesina SA. The prevalence of abdominal obesity and hypertension amongst adults in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med 2011;3:188. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friis-Moller N, Weber R, Reiss P et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV patients--association with antiretroviral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS 2003;17:1179–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glass TR, Ungsedhapand C, Wolbers M et al. Prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients over time: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med 2006;7:404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDonald CL, Kaltman JR. Cardiovascular disease in adult and pediatric HIV/AIDS. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:1185–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crane HM, Van Rompaey SE, Kitahata MM. Antiretroviral medications associated with elevated blood pressure among patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2006;20:1019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palacios R, Santos J, Garcia A et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on blood pressure in HIV-infected patients. A prospective study in a cohort of naive patients. HIV medicine. 2006;7:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thiebaut R, El-Sadr WM, Friis-Moller N et al. Predictors of hypertension and changes of blood pressure in HIV-infected patients. Antivir Ther 2005;10:811–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aoun S, Ramos E. Hypertension in the HIV-infected patient. Curr Hypertens Rep 2000;2:478–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lipshultz SE, Chanock S, Sanders SP et al. Cardiovascular manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in infants and children. Am J Cardiol 1989;63:1489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bloomfield GS, Hogan JW, Keter A et al. Hypertension and obesity as cardiovascular risk factors among HIV seropositive patients in Western Kenya. PloS ONE 2011;6:e22288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mateen FJ, Kanters S, Kalyesubula R et al. Hypertension prevalence and Framingham risk score stratification in a large HIV-positive cohort in Uganda. J Hypertens 2013;31:1372–8; discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Federal Ministry of Health Abuja-Nigeria National Guidelines for HIV and AIDS Treatment and Care in Adolescents and Adults. 2010.

- 20. Chalmers J, MacMahon S, Mancia G et al. 1999 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the World Health Organization. Clin Exp Hypertens 1999;21:1009–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976;16:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okeahialam BN, Ogbonna C, Otokwula AE et al. Cardiovascular epidemiological transition in a rural habitat of Nigeria: the case of mangu local government area. West Afr J Med 2012;31:14–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogunmola OJ, Oladosu OY, Olamoyegun AM. Association of hypertension and obesity with HIV and antiretroviral therapy in a rural tertiary health center in Nigeria: a cross-sectional cohort study. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2014;10:129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krauskopf K, Van Natta ML, Danis RP et al. Correlates of hypertension in patients with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Int Assoc Provi. AIDS Care 2013;12:325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muhammad S, Sani MU, Okeahialam BN. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among HIV-infected Nigerians receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Niger Med J 2013;54:185–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arruda Junior ER, Lacerda HR, Moura LC et al. Risk factors related to hypertension among patients in a cohort living with HIV/AIDS. Braz J Infect Dis 2010;14:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Denue BA, Gashau W, Ekong E, Ngoshe RM. Prevalence of non HIV related co-morbidity in HIV patients on Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy (HAART): A retrospective study. An. Biol Res 2012; 3:3333–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pereira M, Lunet N, Azevedo A, Barros H. Differences in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension between developing and developed countries. J Hypertens 2009;27:963–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA 2003;289:2363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sobry A, Kizito W, Van den Bergh R et al. Caseload, management and treatment outcomes of patients with hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus in a primary health care programme in an informal setting. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:47–57. Epub 2014/05/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olack B, Wabwire-Mangen F, Smeeth L et al. Risk factors of hypertension among adults aged 35-64 years living in an urban slum Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1251. Epub 2015/12/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jerico C, Knobel H, Montero M et al. Hypertension in HIV-infected patients: prevalence and related factors. Am J Hypertens 2005;18:1396–401. Epub 2005/11/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gazzaruso C, Bruno R, Garzaniti A et al. Hypertension among HIV patients: prevalence and relationships to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens 2003;21:1377–82. Epub 2003/06/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baekken M, Os I, Sandvik L, Oektedalen O. Hypertension in an urban HIV-positive population compared with the general population: influence of combination antiretroviral therapy. J Hypertens 2008;26:2126–33. Epub 2008/10/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siven SS, Niiranen TJ, Kantola IM, Jula AM. White-coat and masked hypertension as risk factors for progression to sustained hypertension: the Finn-Home study. J Hypertens 2016;34:54–60. Epub 2015/12/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]