Abstract

A previous study by our group indicated that combined treatment with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and genistein protects against liver fibrosis. The aim of the present study was to elucidate the antifibrotic mechanism of this combination treatment using isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ)-based proteomics in an activated rat hepatic stellate cell (HSC) line. In the present study, HSC-T6 cells were incubated with taurine, EGCG and genistein, and cellular proteins were extracted and processed for iTRAQ labeling. Quantification and identification of proteins was performed using two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomic analysis indicated that the expression of 166 proteins were significantly altered in response to combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein. A total 76 of these proteins were upregulated and 90 were downregulated. Differentially expressed proteins were grouped according to their association with specific Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. The results indicated that the differentially expressed proteins hexokinase-2 and lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1 were associated with glycolysis, gluconeogenesis and lysosome signaling pathways. The expression of these proteins was validated using western blot analysis; the expression of hexokinase-2 was significantly decreased and the expression of lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1 was significantly increased in HSC-T6 cells treated with taurine, EGCG and genistein compared with the control, respectively (P<0.05). These results were in accordance with the changes in protein expression identified using the iTRAQ approach. Therefore, the antifibrotic effect of combined therapy with taurine, EGCG and genistein may be associated with the activation of several pathways in HSCs, including glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the ribosome and lysosome signaling pathways. The differentially expressed proteins identified in the current study may be useful for treatment of liver fibrosis in the future.

Keywords: epigallocatechin gallate, genistein, taurine, isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation, proteomics, rat hepatic stellate cell

Introduction

Liver fibrosis is a common pathological occurrence and increases the risk of cirrhosis, hepatic carcinoma and liver failure (1). Liver fibrosis may be triggered by several types of etiologies include viral hepatitis, chronic alcoholism, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, toxicants or drugs, autoimmune liver disease, genetic and metabolic diseases, and liver congestion (2). It is a complex disease process that requires various different therapies for effective treatment (3). Improved knowledge concerning the initiation and progression of liver fibrosis has resulted in the development of novel therapies. Liver transplantation is the only treatment for patients with cirrhosis and clinical complications (4). Removal of pathogens is the most effective treatment of liver fibrosis; this strategy has been proved to be effective in most of the causes of chronic liver disease (5). Blockade of the tyrosine kinase appears to be a prospect treatment of liver fibrosis. Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been considered to be effective anti-schistosomal and anti-fibrotic drugs, which inhibit and reverse liver fibrosis induced by Schistosoma mansoni (6). Vatalanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that reduces liver fibrosis and sinus capillary vascularization in CCl4-induced fibrotic mice (7). The use of anti-inflammatory drugs has been suggested because inflammation precedes and promotes the progress of liver fibrosis (8). Glucocorticoids are used only for the treatment of liver fibrosis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis and acute alcoholic hepatitis (8). Antioxidants, including vitamin E, silymarin, phosphatidylcholine and methionine, are beneficial in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (9). However, monotherapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors or antioxidants exhibit limited therapeutic effects (10,11). In addition, previous results have suggested that the use of any single pharmacological agent at high doses may induce severe side effects (12). Subsequently, research into the identification of novel effective therapies that treat hepatic fibrosis with fewer side effects is warranted. Combination therapies involving the use of multiple pharmacological agents may be superior to monotherapy due to their potential synergistic effects and limited side effects (13,14). Combination therapies consist of multiple pharmacological agents that target various cellular sites of action and may intervene at different stages of fibrogenesis (15). Therefore, the use of combination therapies may be an effective therapeutic method of treating liver fibrosis.

During the course of fibrogenesis, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) undergo activation and transdifferentiate into myofibroblast-like cells that proliferate and synthesize excess levels of extracellular matrix (ECM) (16,17). Therefore, experimental analysis of HSC activation is an important aspect of research into the pathogenesis hepatic fibrosis. Our group previously reported that combination therapy with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and genistein exhibits a protective effect against alcohol-induced liver fibrosis and also reduces cell proliferation and the expression of fibrogenic factors in the rat HSC-T6 cell line (15,18).

To determine the mechanism by which combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein protects against hepatic fibrosis in the present study, an isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) was used to analyze the proteome of HSC-T6 cells following treatment with combination therapy. The use of cutting-edge iTRAQ-based proteomic profiling with two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry allows for multidimensional protein identification with high sensitivity (19–21). This approach aids the analysis of the entire proteome of a given biological sample in a single experiment (22,23). This advanced proteomic approach was used in the present study to improve mechanistic understanding of hepatic fibrogenesis.

Materials and methods

Pharmacological agents and reagents

Genistein, taurine, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), Tris, SDS, DL-dithiothreitol (DTT), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4), potassium chloride (KCl), acetone and acetonitrile (ACN) were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). EGCG was acquired from Sichuan Yuga Tea Development Co., Ltd. (Sichuan, China). Reagents for iTRAQ were obtained from AB Sciex Pte., Ltd. (Concord, ON, Canada). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), ampholine and apotinin were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). Furthermore, radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China) and Trypsin Gold was acquired from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA).

Cell lines

The HSC-T6 cell line, an immortalized rat HSC line exhibiting a stable phenotype and biochemical characteristics of liver fibrosis, was purchased from the Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University (Hunan, China). HSC-T6 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were passaged via trypsinization every 3 days.

Protein extraction and preparation

HSC-T6 cells were seeded into 50-ml culture flasks at a density of 5×104 cells/ml. Following 24 h culture, cells were treated with or without combined treatment with 0.03 mg/ml taurine, 0.035 mg/ml EGCG and 0.007 mg/ml genistein for 24 h, as previously reported (15). Subsequently cells were trypsinized, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min to obtain cell pellets. Pellets were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer (containing 9 mol/l urea, 4% CHAPS, 40 mmol/l Tris, 1% DTT, 0.8% ampholine and 0.002% apotinin), placed on ice and vortexed every 5 min for a total of 20 min. Cell supernatants were collected following centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatants were then precipitated with pre-chilled acetone (containing 10% v/v TCA) for 2 h and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting pellets were washed with pre-chilled acetone, incubated at 4°C for 2 h and centrifuged again at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were washed with pre-chilled acetone a further three times. The final pellets were lyophilized and protein concentration was determined using bovine serum albumin (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China) as the standard (24).

Protein digestion and peptide iTRAQ labeling

A total of 100 µg processed protein was reduced, blocked with cysteine (25) and digested with Trypsin Gold at a ratio of protein to trypsin of 20:1 at 37°C for 12 h. Following trypsin digestion, peptides were dried using vacuum centrifugation (250 × g, −20°C, 1 h). Subsequently, peptides were reconstituted in 0.5 mol/l tetraethylammonium bromide and processed using 4-plex iTRAQ (both AB Sciex Pte., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's protocol. One unit of iTRAQ reagent was thawed and reconstituted in 150 µl 100% isopropanol. Peptides were individually labeled with iTRAQ tags as follows: Control group, 114; and the combination treatment group, 115. Following incubation for 2 h at room temperature with the iTRAQ reagent, labeled samples were mixed equally prior to further analysis (25).

Strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography

SCX chromatography was performed using a LC-20AB high performance liquid chromatography pump system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). iTRAQ-labeled peptide mixtures were reconstituted with 4 ml buffer A (25 mmol/l NaH2PO4 in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) and loaded onto a Ultremex SCX column (4.6×250 mm, 5 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Peptides were eluted with a gradient of buffer A for 10 min, 5–35% buffer B (25 mmol/l NaH2PO4, 1 mol/l KCl in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) for 11 min and 35–80% buffer B for 1 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The system was maintained in 80% buffer B for 3 min prior to equilibrating with buffer A for 10 min before the next injection. Elution was measured at 214 nm and fractions were collected every min. Eluted peptides were pooled into 20 fractions, desalted with a Strata X C18 column (Phenomenex) and vacuum-dried.

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) analysis

Each fraction was resuspended in buffer A, which consisted of 2% ACN, 0.1% formic acid (FA), and centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 10 min. In each fraction, the final concentration of peptide was ~0.25 µg/µl. Using an auto sampler, 9 µl supernatant was loaded onto a Symmetry C18 column (180 µm ×20 mm, 5 µm). LC-ESI-MS/MS was performed using a nanoACQuity UPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The sample was eluted with buffer A at 2 µl/min for 15 min. Peptides were eluted onto a BEH130 C18 column (100 µm ×10 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters Corporation) for online trapping, desalting and analytical separation. Samples were loaded at a flow rate of 300 nl/min with 5% buffer B (98% ACN and 0.1% FA) for 1 min, eluted with a 40-min gradient from 5–35% buffer B, followed by a 5-min linear gradient to 80% buffer B and maintenance with 80% buffer B for 5 min. Initial chromatographic conditions were restored following 2 min.

A TripleTOF 5600 system fitted with a Nanospray III source (both AB Sciex Pte., Ltd.) and a pulled quartz tip as the emitter (New Objective, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA) was used for data acquisition. Data were acquired using an ion spray voltage of 2.5 kV, curtain gas of 30 PSI, nebulizer gas of 5 PSI and an interface heater (temperature, 150°C). Survey scans were acquired in 250 msec and the top-30 product ion scans were collected if a threshold of 120 counts per sec was exceeded and a +2 to +5 charge state was exhibited. Four time bins were summed for each scan at a pulse frequency value of 11 kHz by monitoring the 40 GHz multichannel TDC detector with 4-anode channel detection. A sweeping collision energy setting of 35±5 eV was applied to all precursor ions for collision-induced dissociation. Dynamic exclusion was set for the ½ peak width (~18 sec) and the precursor was refreshed off of the exclusion list. All iTRAQ experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Changes in the expression of hexokinase-2 (HK2) and lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1 (LAMP 1) were determined by western blot analysis following iTRAQ analysis. Proteins were extracted in the iTRAQ experiment and quantified with a bicinchonic acid protein assay kit (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.). Subsequently, 50 µg total protein were separated in each lane via a 10% SDS-PAGE gels (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% non-fat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST). Subsequently, proteins were washed and incubated with anti-HK2 (cat. no. ab227198), anti-LAMP 1 (cat. no. ab62562; both 1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and anti-GAPDH (cat. no. A00227-1; 1:500; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with secondary antibodies (IRDye® 680LT Goat anti-Rabbit IgG; cat. no. 926-68021; 1:10,000; LI-COR Biosciences; Lincoln, NE, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed three times with TBST and detected using an LI-COR Odyssey® Infrared Imaging system (Odyssey System, Version 2.0.25, LI-COR Biosciences). GAPDH was used as the loading control and total protein content in each lane was quantified using densitometry. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Data analysis and bioinformatics

Data analyses were performed using Protein-Pilot software 4.0 (AB Sciex Pte., Ltd.) and the search parameter for cysteine was determined to be the carbamidomethylation of cysteine. Resulting MS/MS spectra were searched against the International Protein Index (IPI) rat sequence databases (version 3.87; 39,925 sequences; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/IPI/IPIhelp.html) using MASCOT software (version 2.3.02; Matrix Science, London, UK). For protein identification and quantification, a peptide mass tolerance of 8.6 ppm was used for intact peptide masses and 0.05 Da for fragmented ions. One missed cleavage was accepted in the trypsin digests, carbamidomethylation of cysteine was considered to be a fixed modification and the conversion of N-terminal glutamine to pyro-glutamic acid and methionine oxidation were considered variable modifications. All identified peptides had an ion score above the Mascot peptide identity threshold and a protein was considered identified if at least one such unique peptide match was apparent for the protein. For protein-abundance ratios measured using iTRAQ, fold-changes >1.3 or <0.7 were set as the threshold and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The accession numbers of proteins that were significantly differentially expressed were converted to a gene list using the Database for Annotation Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) functional annotation tool (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp) and biological processes, cell components and molecular functions were analyzed using the Gene Ontology terms (26). The protein interaction network mode was created using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database (http://string-db.org/), which quantitatively integrated interaction data for a large number of organisms and transferred information between these organisms where applicable.

Statistical analysis

To determine the proteins that were differentially expressed, another two separate experiments were performed as aforementioned. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. Quantitative variables were analyzed using Student's t-test. Spearman's rank was used to determine whether there was a correlation between parameters. P<0.05 was determined to indicate a statistical significance.

Results

To investigate the response in the HSC-T6 proteome to combination treatment, quantitative proteomic analysis was performed and differentially expressed proteins were identified. A total of 713 distinct proteins were identified and quantified using the MASCOT search algorithm against the IPI rat protein database. According to the set change ratio (fold-change, >1.3 or <0.7; P<0.05), 166 proteins were identified as significantly differentially expressed proteins in all three experiments (data not shown).

Functional classifications of proteins

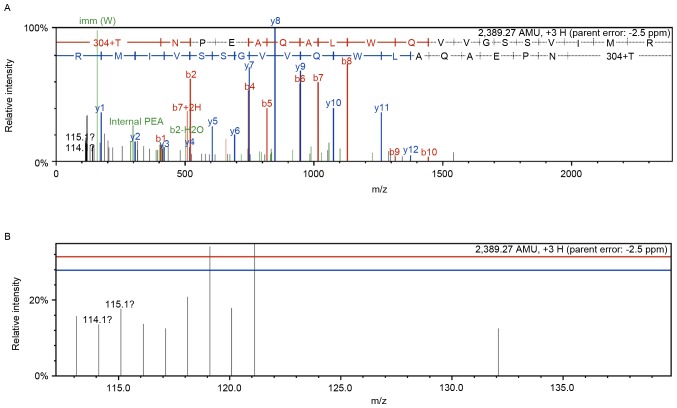

Of the 166 differentially expressed proteins, the expression of 76 were increased and 90 were decreased following combination treatment. Details of the proteins associated with cell signaling pathways associated with fibrosis are listed in Table I. Peptide Mass (https://web.expasy.org/peptide_mass/) and Prot Param (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) tools in ExPASy were used to predict peptides produced by trypsin digestion of heme oxygenase 1 and analyze physical and chemical properties, including peptides molecular weight, isoelectric point, amino acid, atom, molar absorptivity, half-life, instability coefficient, aliphatic amino acid coefficient and average hydrophilicity coefficient. Peptides with good solubility and stability, and satisfying mass spectrometry detectable mass-to-charge ratio were selected, and analyzed for peptide homology using online software BlastP (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) in NBCI database. Skyline (version 4.1; MacCoss Lab Software, Washington, USA) was used to predict specific peptide scanning mass spectrometry fragment information. Therefore, a representative mass spectrum and quantitative information of the heme oxygenase 1 peptide (sequence: PSLFPAASGAFSSFR) is indicated in Fig. 1. First order mass and tandem mass spectra of heme oxygenase 1 were presented in Fig. 1 (the control group, n=114 and the combination treatment group, n=115).

Table I.

Identification of differentially expressed proteins for pathway and protein-protein interaction.

| N | Accession no. | Gene symbol | Protein name | % Cov | Unique peptide | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IPI00215208 | Rpl8 | LOC100360117 60S ribosomal protein L8 | 30.4 | 5 | 0.683±0.026 |

| 2 | IPI00230917 | Rpl18 | 60S ribosomal protein L18 | 19.7 | 3 | 0.623±0.027 |

| 3 | IPI00203523 | Rpl23a | 60S ribosomal protein L23a | 25.0 | 4 | 0.654±0.042 |

| 4 | IPI00231202 | Rps8 | 40S ribosomal protein S8 | 45.7 | 8 | 0.697±0.073 |

| 5 | IPI00324983 | Rps17 | LOC100365810 40S ribosomal protein S17 | 49.6 | 6 | 0.566±0.021 |

| 6 | IPI00358600 | RGD1559972 | Ribosomal protein L27a-like | 17.6 | 2 | 0.541±0.051 |

| 7 | IPI00369491 | RGD1564744 | Ribosomal protein P1-like | 29.2 | 2 | 0.510±0.060 |

| 8 | IPI00765221 | LOC683961 | Ribosomal protein S13-like | 29.0 | 5 | 1.315±0.054 |

| 9 | IPI00206336 | Lamp1 | Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1 | 5.4 | 2 | 1.585±0.013 |

| 10 | IPI00212731 | Ctsd | Cathepsin D | 28.0 | 8 | 1.412±0.010 |

| 11 | IPI00195160 | Psap | Prosaposin | 13.9 | 7 | 1.632±0.032 |

| 12 | IPI00230870 | Clta | Isoform Non-brain of Clathrin light chain A | 13.3 | 2 | 0.687±0.016 |

| 13 | IPI00215580 | Atp6v0c | V-type proton ATPase 16 kDa proteolipid subunit | 11.6 | 1 | 0.615±0.061 |

| 14 | IPI00201057 | Hk2 | Hexokinase-2 | 31.6 | 20 | 0.432±0.030 |

| 15 | IPI00951991 | Aldoa | 45 kDa protein | 58.6 | 13 | 1.313±0.012 |

| 16 | IPI00203690 | Aldh9a1 | 4-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase | 17.3 | 7 | 1.313±0.053 |

| 17 | IPI00364311 | Gpi | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 25.6 | 12 | 1.336±0.024 |

| 18 | IPI00231631 | Eno3 | Beta-enolase | 21.4 | 2 | 1.370±0.038 |

| 19 | IPI00209980 | Pmpcb | Mitochondrial-processing peptidase subunit beta | 12.1 | 4 | 0.567±0.057 |

| 20 | IPI00213245 | Stat1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 isoform alpha | 15.9 | 10 | 0.603±0.098 |

| 21 | IPI00205805 | Timp1 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | 40.1 | 6 | 0.529±0.030 |

| 22 | IPI00200610 | Gfm1 | Elongation factor G, mitochondrial | 18.2 | 10 | 0.699±0.058 |

| 23 | IPI00192246 | Cox5a | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5A, mitochondrial | 28.1 | 3 | 0.602±0.020 |

| 24 | IPI00210945 | Tpm1 | Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain isoform c | 31.3 | 1 | 0.425±0.014 |

| 25 | IPI00187731 | Tpm2 | Isoform 2 of Tropomyosin beta chain | 31.3 | 3 | 0.499±0.026 |

| 26 | IPI00203832 | Plrg1 | Pleiotropic regulator 1 | 4.7 | 2 | 0.679±0.034 |

| 27 | IPI00763263 | Thoc4 | Uncharacterized protein | 23.4 | 4 | 0.574±0.059 |

| 28 | IPI00194222 | Cox4i1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 isoform 1, mitochondrial | 26.6 | 4 | 0.624±0.066 |

| 29 | IPI00200920 | Khsrp | Far upstream element-binding protein 2 | 30.1 | 14 | 0.482±0.015 |

| 30 | IPI00464532 | Pycr2 | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 2 | 25.3 | 3 | 1.483±0.023 |

| 31 | IPI00372370 | P4ha2 | Uncharacterized protein | 23.7 | 9 | 1.317±0.034 |

| 32 | IPI00365868 | Acyp1 | Acylphosphatase-1 | 47.5 | 4 | 1.416±0.094 |

| 33 | IPI00480766 | Acat3 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, cytosolic | 22.2 | 4 | 1.595±0.028 |

| 34 | IPI00195860 | Cox7a2 | Cox7a2 Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7A2, mitochondrial | 12.0 | 1 | 3.396±0.034 |

| 35 | IPI00210920 | Got2 | Aspartate aminotransferase, mitochondrial | 34.7 | 14 | 1.391±0.086 |

| 36 | IPI00214536 | Nop58 | Nucleolar protein 58 | 31.1 | 11 | 1.322±0.005 |

| 37 | IPI00197164 | Icam1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | 10.8 | 5 | 1.419±0.010 |

| 38 | IPI00371124 | Srsf9 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 9 | 21.7 | 4 | 1.455±0.064 |

| 39 | IPI00411215 | Phf5a | PHD finger-like domain-containing protein 5A | 18.2 | 2 | 1.379±0.021 |

| 40 | IPI00192936 | Magoh | Protein mago nashi homolog | 51.4 | 7 | 1.369±0.039 |

| 41 | IPI00357978 | Srsf6 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 6 | 11.8 | 3 | 1.354±0.029 |

| 42 | IPI00372819 | Snrpc | U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein C | 18.9 | 2 | 1.741±0.036 |

| 43 | IPI00188158 | Hmgcs1 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic | 17.1 | 8 | 1.733±0.025 |

| 44 | IPI00204738 | Aacs | Acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase | 4.5 | 3 | 1.312±0.021 |

| 45 | IPI00766047 | LOC679203 | TH1-like isoform 4 | 7.3 | 4 | 1.756±0.057 |

Ratio indicated the specific value of protein expression between combination treatment with epigallocatechin gallate and genistein group (iTRAQ label 115) and the control group (iTRAQ label 114). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). % Cov, percentage coverage of protein; iTRAQ, isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation. Ratios >1.3 represent an increase in protein expression and ratios <0.7 represent a decrease in protein expression (P<0.05).

Figure 1.

Identification of heme oxygenase 1. (A) Representative tandem mass spectrometry identified the peptides from heme oxygenase 1 (peptide sequence: PSLFPAASGAFSSFR). (B) Quantitative information for peptide (peptide sequence: PSLFPAASGAFSSFR). The Control and combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein groups were labeled with isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation reagents 114 and 115, respectively.

The 166 differentially expressed proteins were analyzed using the DAVID functional annotation tool to determine their cellular components, molecular functions and participation in biological processes (data not shown). The top three biological processes included cellular processes (11.86%), single-organism processes (10.09%) and metabolic processes (9.85%). The top three molecular function categories included binding (49.82%), catalytic activity (24.21%) and structural molecule activity (6.67%). The top three associated cellular components included the cell (37.60%), organelle (27.15%) and membrane (11.55%).

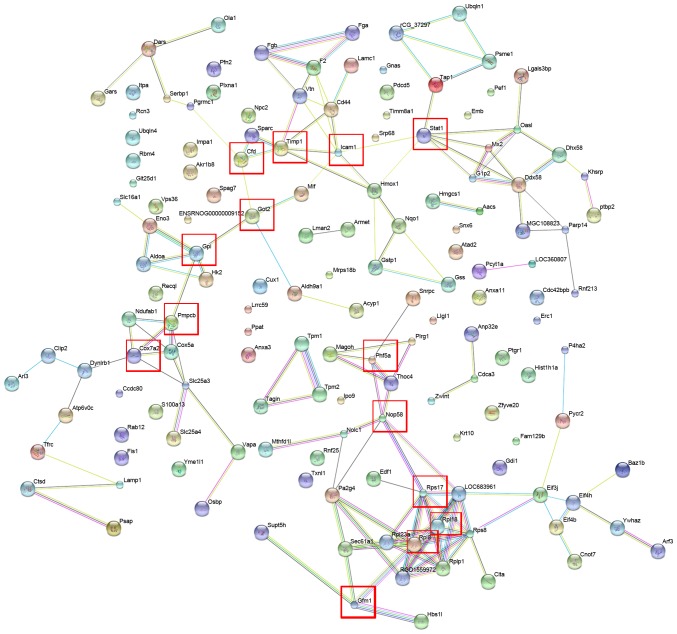

Protein-protein interaction analysis

In order to characterize the protein-protein interactions of the identified differentially expressed proteins, the STRING database was assessed to establish a protein-protein interaction network (Fig. 2). Proteins that responded significantly to combination treatment and interacted with each other included Stat1, Icaml, Timp1, Cfd, Got2, Gpi, Pmpcb, Cox7a2, Phf5a, Nop58, Rps17, Rpl18, Rp18 and Gfm1 (Fig. 2). These seed proteins serve important roles in catalytic activity, biological regulation and coagulation systems (27–33). Furthermore, pathway annotation indicated that certain differentially expressed proteins, including glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) and ribosomal protein L8 (RPL8), were involved in eight different Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (glycolysis and gluconeogenesis; lysosome metabolism; ribosome metabolism; spliceosome metabolism; butanoate metabolism; arginine and proline metabolism; cardiac muscle contraction; and pyruvate metabolism signaling pathways; Table II). Notably, GPI is a crucial enzyme that catalyzes the interconversion of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis (34). Rp18 is a component of the 60S subunit of the ribosome that is involved in the protein synthesis pathway. Depletion of Rp18 impairs drosophila development and is associated with apoptosis (35). The results suggest that the interactions and signaling pathways associated with the differentially expressed proteins may serve important roles in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis.

Figure 2.

Protein-protein interaction networks of the differentially expressed proteins using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes. Proteins that responded significantly to combination treatment and interacted with each other are indicated in red boxes.

Table II.

Pathway annotation of the differentially expressed proteins involved in eight different Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways.

| Pathway | Differentially expressed proteins with pathway annotation |

|---|---|

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | Hk2, Aldoa, Aldh9a1, Gpi, Eno3 |

| Lysosome | Atp6v0c, Clta, Psap, Ctsd, Lamp1 |

| Ribosome | Rpl8, Rpl18, Rps8, Rps17, Rpl23a, LOC683961 RGD1559972, RGD1564744 |

| Spliceosome | Magoh, Thoc4, Snrpc, Srsf9, Phf5a, Srsf6, Plrg1 |

| Butanoate metabolism | Hmgcs1, Aldh9a1, Aacs, LOC679203 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | Aldh9a1, Khsrp, Pycr2, P4ha2 |

| Cardiac muscle contraction | RGD1559972, Cox5a, Tpm1, Tpm2 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | Aldh9a1, Acyp1, Acat3 |

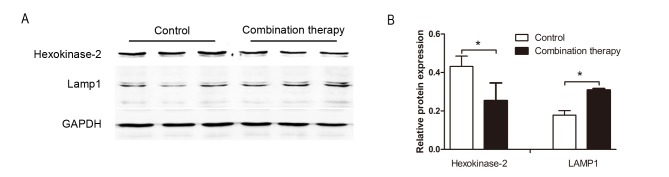

Confirmation of differentially expressed proteins using western blot analysis

To further investigate the expression of the differentially expressed proteins obtained from the iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics study, western blot analysis was performed to assess the expression of HK2 and LAMP 1. Levels of HK2 and LAMP 1 were significantly downregulated and upregulated in HSC-T6 cells following combination therapy, respectively (each, P<0.05; Fig. 3). This pattern was similar to the changes in the expression of these proteins obtained following iTRAQ (Table I), supporting the validity of the proteomic analysis performed in the present study.

Figure 3.

Differentially expressed protein expression levels using western blot analysis. (A) Hexokinase-2 and LAMP 1 protein levels were downregulated and upregulated in HSC-T6 cells treated with taurine, EGCG and genistein compared with the control group. (B) Densitometric analysis indicated that these differences were significant. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. This trend was similar to the changes in protein expression obtained using the isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantification. GAPDH was used as a loading control. *P<0.05. LAMP 1, lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1.

Discussion

A variety of biological factors are involved in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. As an approach to investigate the multiple signaling pathways that may contribute to liver fibrosis, our group previously reported that combination therapy with taurine, EGCG and genistein exhibits a protective effect against liver fibrosis in vivo and in vitro (15,18). In the present study, the mechanistic underpinnings of this effect in HSC-T6 cells were evaluated using a proteomic approach. Proteomic analysis is a powerful tool for revealing the molecular mechanisms of disease development, and is useful for the identification of disease-specific biomarkers and evaluating biological networks for drug therapy (36,37). Previous studies have also revealed that the optimal approach for developing novel therapies is to characterize key regulatory pathways and networks (38,39).

One of the primary objectives of treatments for liver fibrosis is the inhibition of proliferation or the induction of apoptosis of activated HSC cells (40). Therefore, in the present study, activated HSC-T6 cells were used to study the anti-fibrotic effects of combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein. iTRAQ-based proteomics was used to analyze the molecular targets of combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein in HSC-T6 cells. A total of 166 differentially expressed proteins were identified, which represent a diverse array of molecular weights, isoelectric point and protein functions. In a previous study by our group, it was demonstrated that changes in the expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 and −2, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and collagen type (Col)-I mRNA were associated with hepatic fibrogenesis in HSC-T6 cells (10). The present study also revealed similar results regarding the expression of TGF-β1, TIMP-1, MMP-2, TIMP-2 and Col-1 proteins. In the present study, due to the set change ratio (fold-change >1.3 or <0.7), the proteins TIMP-2 and Col-1 were not regarded as significantly differentially expressed. Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis revealed that all 166 differentially expressed proteins are involved in various biological processes, including metabolic processes, single-organism processes, cellular processes, response to stimuli, cell necrosis, reproduction and cell apoptosis (data not shown). Additionally, several identified significantly differentially expressed proteins, including Hk2, Aldoa, Aldh9a1, Gpi, Eno3, Atp6v0c, Clta, Psap, Ctsd and Lamp1, were associated with eight different KEGG pathways that connected with each other to form a network (Table II).

Based on the present data, it was speculated that the antifibrotic activity associated with combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein in HSC-T6 cells was associated with multiple biological processes and signaling pathways. From these indicated associations, the cellular processes of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, and the signaling pathways of lysosome and ribosome synthesis were suggested to be of particular importance. Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis serve important roles in supplying ATP for hypoxic metabolism, cellular proliferation and apoptosis (41). Several enzymes and proteins, including hexokinase-2, aldolase A and glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, associated with glycolysis and gluconeogenesis may be potential molecular targets in pancreatic, breast and gastrointestinal tumors (42,43). The ribosome signaling pathway has been implicated in a wide variety of biological functions, including cell cycle progression, apoptosis and DNA damage responses (44–47). Furthermore, the lysosomal signaling pathway may be involved in a series of pathological processes, including cell death, necrosis, apoptosis and autophagy (48).

In the early phase of liver damage or inflammation, the hepatocyte microenvironment becomes hypoxic, leading to a failure in oxidative energy generation and a switch to the glycolysis and gluconeogenesis pathway to produce ATP (3). HK2 is the rate-limiting enzyme in the glycolysis and gluconeogenesis pathway and its expression is significantly enhanced in different types of cancer, including metastatic colorectal cancer, lung cancer and gastric cancer (49–52) and rapidly proliferating cells, including those in the developing embryo (53). Previous studies have reported that HK2 binding in the mitochondrial membrane may promote tumor growth by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting cell proliferation (54,55). This suggests that HK2 may be a potential molecular target in the treatment of various diseases (56,57). The results of the present study indicate that combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein significantly inhibits the expression of HK2. This may potentially lead to improved oxygenation in the cell microenvironment and induce the apoptosis of HSC-T6 cells. Thus, downregulation of HK2 may contribute to the antifibrotic effects associated with combination therapy.

GPI is a crucial enzyme that catalyzes the interconversion of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis (34). Furthermore, GPI is secreted by tumor cells and stimulates cell migration (58). In hepatocellular carcinoma cells, GPI may promote cell movement and activate the synthesis of MMP-3 (59). Upregulated GPI expression in response to combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein in HSC-T6 cells, as identified in the current study, may induce MMP-3 synthesis. MMP-3 is associated with the degradation of the ECM (60); therefore, this upregulation may promote ECM degradation and contribute to the reversal of hepatic fibrosis.

Autophagy is a degradation and recirculation system in eukaryotic cells that is required for the induction of apoptosis (61,62). During autophagy, lysosomes serve an important role in the degradation and recycling of material within the terminal organelle (63). The protein cathepsin D is a major incision enzyme in lysosomes that maintains cell metabolism by degrading intracellular substances (64). The overexpression of cathepsin D may stimulate a series of pathological processes, including cell necrosis, apoptosis and autophagy (48,65). Another important lysosomal protein is LAMP 1, which may induce autophagy and apoptosis (65). A previous study indicated that LAMP 1 was upregulated and induced apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells following treatment with cisplatin (66). In the present study, cathepsin D and LAMP 1 were upregulated in HSC-T6 cells following combination treatment. In Table I, relative LAMP1 protein expression was increased at a ratio of 1.585±0.013 after treatment and cathepsin D was increased at a ratio of 1.412±0.010. Relative HK2 protein expression was decreased at a ratio of 0.432±0.030 following treatment.

These results suggest that the upregulation of cathepsin D may lead to the interaction with LAMP 1 in the lysosome pathway, initiating HSC autophagy and apoptosis, thus contributing to the antifibrotic effect of the combination treatment. Ribosome proteins are crucial components of the ribosomal subunits that function in ribosome assembly and protein synthesis (67,68). The abnormal expression of specific ribosome proteins may be responsible for several human conditions, including Diamond-Blackfan anemia (69), Turner syndrome (70), hearing loss (71) and cancer (72).

In conclusion, combination treatment with taurine, EGCG and genistein induced antifibrotic effects in HSC-T6 cells in at least three ways: i) Regulation of energy metabolism in HSCs via glycolysis and gluconeogenesis; ii) protection of the liver via the ribosome signaling pathway, with subsequent effects on numerous biological functions, including cell cycle progression, protein synthesis and DNA damage responses; and iii) regulation of apoptosis and autophagy via the lysosomal signaling pathway. Although the exact roles of these pathways remain to be elucidated, the present study has enhanced understanding of the molecular mechanism by which combination therapy alleviates liver fibrosis. Furthermore, the present study also demonstrated that protein profiling using iTRAQ-based proteomics is a powerful method of performing quantitative proteome analysis in cell models in response to therapy. Furthermore, the results suggest that iTRAQ-based proteomics may be used to identify underlying mechanisms of action and potential targets for novel therapies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81160063, 81360078 and 81460128); the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2013GXNSFBA019167) and the Foundation of High-Incidence-Tumor Prevention & Treatment, Guangxi Medical University, Ministry of Education (grant no. GK2013-13-A-01-03).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

YL analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. MZ and YH performed the experiments. ML and XZ designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University (Nanning, China) approved the experimental animal protocol of the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis-from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl 1):S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad A, Ahmad R. Understanding the mechanism of hepatic fibrosis and potential therapeutic approaches. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:155–167. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.96445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonis PAL, Friedman SL, Kaplan MM. Is liver fibrosis reversible? N Engl J Med. 2001;344:452–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berenguer M. Hepatitis C virus and liver transplantation. Springer; 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammel P, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, Ratouis A, Sauvanet A, Fléjou JF, Degott C, Belghiti J, Bernades P, Valla D, et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:418. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobhy MMK, Mahmoud SS, El-Sayed SH, Rizk EMA, Raafat A, Negm MSI. Impact of treatment with a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Genistein) on acute and chronic experimental Schistosoma mansoni infection. Exp Parasitol. 2018;185:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong LJ, Li H, Du YJ, Pei FH, Hu Y, Zhao LL, Chen J. Vatalanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, decreases hepatic fibrosis and sinusoidal capillarization in CCl4-induced fibrotic mice. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:2604–2610. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Progressive fibrosis during corticosteroid therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2004;39:1631–1638. doi: 10.1002/hep.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieber CS. Role of oxidative stress and antioxidant therapy in alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver diseases. Adv Pharmacol. 1996;38:601–628. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)61001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sánchez-Valle V, Chávez-Tapia NC, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. Role of oxidative stress and molecular changes in liver fibrosis: A review. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:4850–4860. doi: 10.2174/092986712803341520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Distler JH, Distler O. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of fibrotic diseases such as systemic sclerosis: Towards molecular targeted therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(Suppl 1):i48–i51. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.120196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebhardt R. Oxidative stress, plant-derived antioxidants and liver fibrosis. Planta Med. 2002;68:289–296. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-26761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carragher NO, Unciti-Broceta A, Cameron DA. Advancing cancer drug discovery towards more agile development of targeted combination therapies. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:87–105. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar M, Sarin SK. Systematic review: Combination therapies for treatment-naive chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuo L, Liao M, Zheng L, He M, Huang Q, Wei L, Huang R, Zhang S, Lin X. Combination therapy with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate and genistein for protection against hepatic fibrosis induced by alcohol in rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:1802–1810. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman SL. Mechanism of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524282C1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Luo Y, Zhang X, Lin X, He M, Liao M. Combined taurine, epigallocatechin gallate and genistein therapy reduces HSC-T6 cell proliferation and modulates the expression of fibrogenic factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:20543–20554. doi: 10.3390/ijms141020543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallick P, Kuster B. Proteomics: A pragmatic perspective. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:695–709. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song X, Bandow J, Sherman J, Baker JD, Brown PW, McDowell MT, Molloy MP. iTRAQ experimental design for plasma biomarker discovery. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:2952–2958. doi: 10.1021/pr800072x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glen A, Gan CS, Hamdy FC, Eaton CL, Cross SS, Catto JW, Wright PC, Rehman I. iTRAQ-facilitated proteomic analysis of human prostate cancer cells identifies proteins associated with progression. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:897–907. doi: 10.1021/pr070378x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanash SM, Bobek MP, Rickman DS, Williams T, Rouillard JM, Kuick R, Puravs E. Integrating cancer genomics and proteomics in the post-genome era. Proteomics. 2015;2:69–75. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200201)2:1<69::AID-PROT69>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivas PR, Kramer BS, Srivastava S. Trends in biomarker research for cancer detection. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:698–704. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson GL. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal Biochem. 1977;83:346–356. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao W, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, He M, Zang N, Zhou Y, Liao M. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of combination therapy with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate, and genistein on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Toxicol Lett. 2015;232:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao W, Li Y, Li M, Zhang X, Liao M. Txn1, Ctsd and Cdk4 are key proteins of combination therapy with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate and genistein against liver fibrosis in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;85:611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Z, Meng Q, Zhao Y, Han R, Huang S, Li M, Wu X, Cai W, Wang H. Resveratrol promoted interferon-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis of SMMC7721 cells by activating the SIRT/STAT1. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2018;38:261–271. doi: 10.1089/jir.2017.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng YZ, Xue MZ, Shen HJ, Li XG, Ma D, Gong Y, Liu YR, Qiao F, Xie HY, Lian B, et al. PHF5A epigenetically inhibits apoptosis to promote breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3190–3206. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wingren AG, Parra E, Varga M, Kalland T, Sjögren HO, Hedlund G, Dohlsten M. T cell activation pathways: B7, LFA-3, and ICAM-1 shape unique T cell profiles. Crit Rev Immunol. 1995;15:235–253. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v15.i3-4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Lin B, Brems JJ, Gamelli RL. Hepatic apoptosis can modulate liver fibrosis through TIMP1 pathway. Apoptosis. 2013;18:566–577. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sookoian S, Castaño GO, Scian R, Gianotti Fernández T, Dopazo H, Rohr C, Gaj G, Martino San J, Sevic I, Flichman D, Pirola CJ. Serum aminotransferases in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are a signature of liver metabolic perturbations at the amino acid and Krebs cycle level. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:422–434. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.118695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swan EJ, Maxwell AP, Mcknight AJ. Distinct methylation patters in genes that affect mitochondrial function are associated with kidney disease in blood-derived DNA from individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1110–1115. doi: 10.1111/dme.12763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenney SP, Meng XJ. Identification and fine mapping of nuclear and nucleolar localization signals within the human ribosomal protein S17. Plos One. 2015;10:e0124396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe H, Takehana K, Date M, Shinozaki T, Raz A. Tumor cell autocrine motility factor is the neuroleukin/phosphohexose isomerase polypeptide. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2960–2963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsley DL, Sandler L, Baker BS, Carpenter AT, Denell RE, Hall JC, Jacobs PA, Miklos GL, Davis BK, Gethmann RC, et al. Segmental aneuploidy and the genetic gross structure of the Drosophila genome. Genetics. 1972;71:157–184. doi: 10.1093/genetics/71.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogeweg P. The roots of bioinformatics in theoretical biology. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dix M, Cravatt B. Global mapping of the topography and magnitude of proteolytic events in apoptosis. Cell. 2008;134:679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee MJ, Ye AS, Gardino AK, Heijink AM, Sorger PK, MacBeath G, Yaffe MB. Sequential application of anticancer drugs enhances cell death by rewiring apoptotic signaling networks. Cell. 2012;149:780–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu LL, Zhou CC, Yao S, Yu JY, Liu B, Bao JK. Plant lectins: Targeting programmed cell death pathways as antitumor agents. Int J Biochem Cell B. 2011;43:1442–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5(Suppl 1):S26. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-S1-S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rui L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:177–197. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou YY, Cheng CL, Baranenko D, Wang JP, Li YZ, Lu WH. Effects of acanthopanax senticosus on brain injury induced by simulated spatial radiation in mouse model based on pharmacokinetics and comparative proteomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E159. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan XP, Xie P, Bu Z, Zou XT. Changes in hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism-related parameters in domestic pigeon (Columba livia) during incubation and chick rearing. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2018;102:e558–e568. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volarević S, Thomas G. Role of S6 phosphorylation and S6 kinase in cell growth. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2000;65:101–127. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(00)65003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volarevic S, Stewart MJ, Ledermann B, Zilberman F, Terracciano L, Montini E, Grompe M, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Proliferation, but not growth, blocked by conditional deletion of 40S ribosomal protein S6. Science. 2000;288:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lohrum MA, Ludwig RL, Kubbutat MH, Hanlon M, Vousden KH. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:577–587. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00134-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen FW, Ioannou YA. Ribosomal proteins in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Int Rev Immunol. 1999;18:429–448. doi: 10.3109/08830189909088492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin AP, Zhang HL, Qin ZH. Mechanisms of lysosomal proteases participating in cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal death. Neurosci Bull. 2008;24:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s12264-008-0117-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Peng R, Chen X, Jia R, Huang C, Huang Y, Xia L, Guo G. Effect of HK2, PKM2 and LDHA on Cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:5553–5560. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolf A, Agnihotri S, Munoz D, Guha A. Developmental profile and regulation of the glycolytic enzyme hexokinase 2 in normal brain and glioblastoma multiforme. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;44:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ong LC, Jin Y, Song IC, Yu S, Zhang K, Chow PK. 2-[18F]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake in human tumor cells is related to the expression of GLUT-1 and hexokinase II. Acta Radiol. 2009;49:1145–1153. doi: 10.1080/02841850802482486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goel A, Mathupala SP, Pedersen PL. Glucose metabolism in cancer. Evidence that demethylation events play a role in activating type II hexokinase gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2015;278:15333–15340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolf A, Agnihotri S, Micallef J, Mukherjee J, Sabha N, Cairns R, Hawkins C, Guha A. Hexokinase 2 is a key mediator of aerobic glycolysis and promotes tumor growth in human glioblastoma multiforme. J Exp Med. 2011;208:313–326. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pedersen PL, Mathupala S, Rempel A, Geschwind JF, Ko YH. Mitochondrial bound type II hexokinase: A key player in the growth and survival of many cancers and an ideal prospect for therapeutic intervention. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1555:14–20. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(02)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pastorino JG, Hoek JB. Hexokinase II: The integration of energy metabolism and control of apoptosis. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:1535–1551. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mathupala SP, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. Hexokinase II: Cancer's double-edged sword acting as both facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to mitochondria. Oncogene. 2006;25:4777–4786. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jae HJ, Jin WC, Park HS, Lee MJ, Lee KC, Kim HC, Yoon JH, Chung H, Park JH. The antitumor effect and hepatotoxicity of a hexokinase II inhibitor 3-bromopyruvate: In vivo investigation of intraarterial administration in a rabbit VX2 hepatoma model. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:596–603. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.6.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liotta LA, Mandler R, Murano G, Katz DA, Gordon RK, Chiang PK, Schiffmann E. Tumor cell autocrine motility factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3302–3306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ho JC, Cheung ST, Patil M, Chen X, Fan ST. Increased expression of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor attachment protein 1 (GPAA1) is associated with gene amplification in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1330–1337. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu FL, Liao MH, Lee JW, Shih WL. Induction of hepatoma cells migration by phosphoglucose isomerase/autocrine motility factor through the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott RC, Juhász G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, Gasco M, Garrone O, Crook T, Ryan KM. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liang ZQ, Wang X, Li LY, Wang Y, Chen RW, Chuang DM, Chase TN, Qin ZH. Nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent cyclin D1 induction and DNA replication associated with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated apoptosis in rat striatum. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1295–1309. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen JW, Pan W, D'Souza MP, August JT. Lysosome-associated membrane proteins: Characterization of LAMP-1 of macrophage P388 and mouse embryo 3T3 cultured cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;239:574–586. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90727-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen JW, Madamanchi N, Madamanchi NR, Trier TT, Keherly MJ. Lamp-1 is upregulated in human glioblastoma cell lines induced to undergo apoptosis. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:365–374. doi: 10.1007/BF02258379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ray PS, Arif A, Fox PL. Macromolecular complexes as depots for releasable regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jewett MC, Fritz BR, Timmerman LE, Church GM. In vitro integration of ribosomal RNA synthesis, ribosome assembly, and translation. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:678. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Draptchinskaia N, Gustavsson P, Andersson B, Pettersson M, Willig TN, Dianzani I, Ball S, Tchernia G, Klar J, Matsson H, et al. The gene encoding ribosomal protein S19 is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;21:169–175. doi: 10.1038/5951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fisher EMC, Beer-Romero P, Brown LG, Ridley A, McNeil JA, Lawrence JB, Willard HF, Bieber FR, Page DC. Homologous ribosomal protein genes on the human X and Y chromosomes: Escape from X inactivation and possible implications for turner syndrome. Cell. 1990;63:1205–1218. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90416-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O'Brien TW, O'Brien BJ, Norman RA. Nuclear MRP genes and mitochondrial disease. Gene. 2005;354:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruggero D, Pandolfi PP. Does the ribosome translate cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nrc1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and/or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.