Abstract

Despite continuing improvements in multimodal therapies, gastro-esophageal malignances remain widely prevalent in the population and is characterized by poor overall and disease-free survival rates. Due to the lack of understanding about the pathogenesis and absence of reliable markers, gastro-esophageal cancers are associated with delayed diagnosis. The increasing understanding about cancer's molecular landscape in the recent years, offers the possibility of identifying ‘targetable’ molecular events and in particular facilitates novel treatment strategies and development of biomarkers for early stage diagnosis. At least 98% of our genome is actively transcribed into non-coding RNAs encompassing long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) constituted of transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with no protein-coding capacity. Many studies have demonstrated that lncRNAs are functional genomic elements playing pivotal roles in main oncogenic processes. LncRNA can act at multiple levels developing a complex molecular network that can modulate directly or indirectly the expression of genes involved in tumorigenesis. In this review, we focus on lncRNAs as emerging players in gastro-esophageal carcinogenesis and critically assess their potential as reliable noninvasive biomarkers and in next generation targeted therapies.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Esophageal cancer, Long noncoding RNAs, Biomarkers

1. Introduction

Less than 2% of the human genome consists of protein-coding genes, and at least 98% of our genome is actively transcribed into non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which were previously regarded as transcriptional “noise” or “junk” [1]. NcRNAs is a broad umbrella term that includes long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in addition to pseudogenes, telomeric repeat-containing RNAs (TERRAs), transcribed ultra-conserved regions (T-UCRs), enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) and piwi-RNA (piRNAs) [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. LncRNAs in essence codes for RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with no protein-coding capacity [6]. Intriguingly, in contrast with this definition some of them could be translate into short (∼40AA) nonfunctional peptides [7], so should be better to talk of no/little protein coding capacity. Their present estimated number in the human genome is about 167,000 and it is expected to increase further [8].

LncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II/III, show epigenetic features common to protein-coding genes, such as trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 4 at the transcriptional start site and trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 36 throughout the gene body and are commonly subjected to splicing [9]. Many studies have demonstrated that lncRNAs are functional genomic elements, and exhibit proximity to disease-associated genomic polymorphisms, and cancer-specificity [10]. The dysregulation of lncRNA has been extensively reported in the context of carcinogenesis and metastasis.

In this present review, we will focus on lncRNAs as novel and emerging players in the wide field of gastro-esophageal carcinogenesis, concentrating on their working mechanism and subsequent implications for diagnosis, follow-up and treatment.

2. Biology of LNCRNAs

Despite the multiple emerging functions exerted by lncRNAs, several aspects pertaining to structural functionality and biological relevance of lncRNAs remain unclear. Additionally, in contrast to mRNAs and proteins, the function of lncRNA cannot simply be described according to their structure sequence because of their inherent complexity and diversity [[11], [12], [13]]. LncRNAs exhibit high evolutionary conservation, actively regulated promoters, a specified length (from 200 to 100,000 nucleotides), can be either polyadenylated or non-polyadenylated, undergo alternative splicing, tend to have a low sequence identity (nucleic acid sequence of ∼50–60%) and a low abundance (their median expression levels are ∼10 times lower than those of mRNAs) [10,14,15]. Another important element of lncRNAs is their high tissue-specificity, particularly linked to their carcinogenic effect [15].

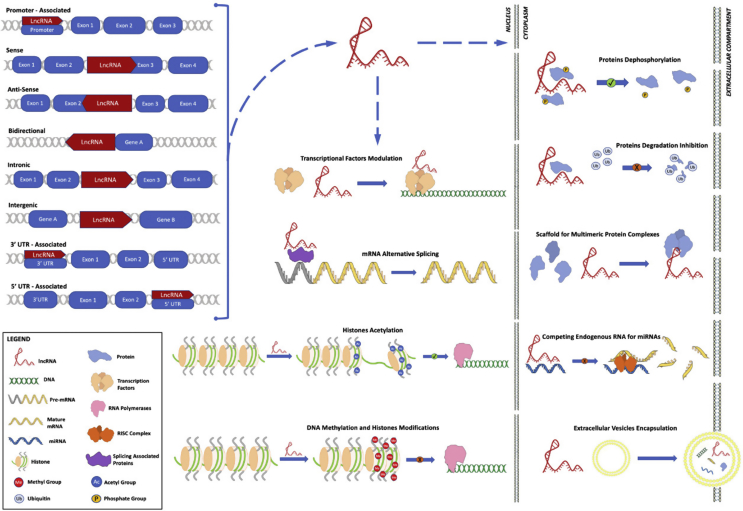

From the genetic point of view, the lncRNAs can be categorized as: (i) promoter-associated: non-coding transcripts deriving from the promoter region; (ii) sense oriented: lncRNAs and mRNAs are present on the same strand, with some overlapping exons; (iii) antisense oriented: lncRNAs and mRNAs are present on the same strand on the opposite chain, with at least one exon overlapping; (iv) bidirectional: the transcription start site of the lncRNA and its adjacent gene are on the antisense strand; (v) intronic: lncRNAs that begin their transcription inside an intron of protein-coding gene without overlapping exons; (vi) intergenic: lncRNAs that lies within the genomic interval between two protein-coding genes, as a separate unit; (vii) 3′UTR-associated transcripts: lncRNAs overlapping 3′UTR region; (viii) 5′UTR-associated transcripts: lncRNAs overlapping 5′UTR region [[16], [17], [18], [19]].

The above described location-based classification tries to capture a snapshot of the contemporary biological knowledge and it could rapidly evolve to include functional attributes in accordance with novel insights and discoveries.

Mechanistically, lncRNAs can control the timing and degree of gene expression by acting both in cis- (local control of genes neighboring) and trans- (control of distant genes) regulation at different levels: (i) epigenetic modifications: reversible and heritable changes in gene expression in the absence of a change in the DNA sequence; this modifications include recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genomic loci, methylation of DNA and histone acetylation; (ii) transcriptional regulations: promoters and transcription factors activity modulation; (iii) post-transcriptional regulations: lncRNAs can influence mRNA alternative splicing, or can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) serving as molecular sponges for miRNAs or can participate in the post-translational modifications of proteins; (iv) other mechanisms encompass the association with other lncRNAs; (v) finally, they might be also affected by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [20]. Fig. 1 summarized these biological knowledges.

Fig. 1.

LncRNAs biogenesis and biological acting mechanisms.

3. LNCRNAs in esophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [21] and has two major histotypes: squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and adenocarcinoma (EAC). EC has a poor prognosis: the overall 5-year survival of stage III is about 10–15% and the median survival time of stage IV is less than 1 year [22]. Given this unfavorable prognosis, many recent studies have focused on novel therapeutic targets, including lncRNAs. Table 1 summarized and integrate these studies.

Table 1.

Dysregulated lncRNAs in ESCC.

| EXPRESSION | LncRNA | GENOME LOCATION | CARCINOGENETIC ROLES | TARGETS | MOLECULAR MECHANISMS | CLINICO-PATHOLOGICAL CORRELATIONS | INVESTIGATED MATERIALS | REFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | MALAT1 | 11q13.1 | Proliferation, migration, invasion | miR-101, miR-217, EZH2 | CeRNA for miR-101 and miR-217; increases of Wnt/β-catenin pathway via EZH2 | Stage, lymph nodes MTS, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [27,28] |

| Upregulated | HOTAIR | 12q13.13 | Proliferation, migration, invasion | PRC2, LSD1, WIF-1 | Increase of Wnt/β-catenin pathway by epigenetic modulation of WIF-1 gene expression; SNPs | Stage, lymph node MTS, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [[30], [31], [32], [33]] |

| Upregulated | ANRIL | 9p21.3 | Proliferation | CDK6, mTOR, E2F1, p15, p16, PRC1, PRC2 | Increase expression of CDK6, mTOR and E2F1 through: p15 silencing by PRC2 and p16 silencing by PRC1; E2F1 induce ANRIL expression | NA | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [[38], [39], [40], [41]] |

| Upregulated | H19 | 11p15.5 | Proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, EMT | REPS2, IGF2 | Precursor of miR-675-5p, which upregulate RalBP1/RAC1/CDC42 pathway through the inhibition of REPS2; silencing IGF2 | Depth of invasion, grade, stage, lymph node MTS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [44,221] |

| Upregulated | Linc-POU3F3 | 2q12.1 | Proliferation, dedifferentiation | POU3F3, EZH2 | Epigenetic silencing POU3F3 via EZH2; increased plasma levels in ESCC patients | NA | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma | [46,73] |

| Upregulated | TUG1 | 22q12.2 | Proliferation, migration | HOXB7, EZH2 | Epigenetic silencing HOXB7 via EZH2 | Chemotherapy resistance, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [222] |

| Upregulated | SOX2-OT | 3q26.33 | Proliferation | SOX2 | SOX2-OT and SOX2 are co-upregulated | NA | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [53,54,223] |

| Upregulated | UCA1 | 19p13.12 | Proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, stemness, | miR-204, SOX4, p27, HK2 | CeRNA for miR-204, which regulate SOX4 | Differentiation, stage, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [[61], [62], [63]] |

| Upregulated | CBR3-AS1 | 21q22.12 | Proliferation, apoptosis | NA | NA | Stage, lymph node MTS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [65] |

| Upregulated | FOXCUT | 6p25.3 | Proliferation, migration, invasion | FOXC1 | NA | Differentiation, lymph node MTS, stage, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [67] |

| Upregulated | SPRY4-IT1 | 5q31.3 | EMT, motility | VIM, FN, E-Cad | Increase Vim, FN and SNAIL and decrease E-Cad expression | Differentiation, lymph node MTS, stage | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [75,77,78] |

| Upregulated | CCAT2 | 8q24.21 | Chromosomal instability altered DNA replication | MYC | Poor information: CCAT2 is approximately 335 kb away form MYC gene and their amplification often occurs simultaneously | Stage, OS | Human tissue samples | [79] |

| Upregulated | CASC9 | 8q21.13 | Migration, invasion | PDCD4, EZH2 | Epigenetic downregulation of PDCD4 via EZH2 | Differentiation, stage | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [80] |

| Upregulated | CCAT1 | 8q24.21 | Proliferation, migration | SPRY4, PRC2 | Epigenetic downregulation of SPRY4 via PRC2 | NA | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [82] |

| Upregulated | PCAT-1 | 8q24.21 | Invasion | EZH2 | Poor information: could epigenetically regulate transcription via EZH2 | Lymph node MTS, stage, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [83,84] |

| Upregulated | PEG10 | 7q21.3 | Proliferation, invasion | NA | NA | Lymph node MTS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [85] |

| Downregulated | TUSC7 | 3q13.31 | Proliferation | miR-224, DESC1 | Increase DESC1 expression via inhibiting miR-224 | Chemo-radio-therapy resistance, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [86,224] |

| Downregulated | LOC100130476 | 6q23.3 | Proliferation, invasion | NA | NA | Stage, differentiation | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [89,90,225] |

3.1. LncRNAs involved in ESCC

3.1.1. Upregulated lncRNAs

-

−

MALAT1 (Metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; also known as NEAT2: nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 2) is a nuclear lncRNA, located in the chromosome 11q13, initially reported to be overexpressed in invasive non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and acting as an oncogene [23,24]. MALAT1 is strongly conserved among mammals and is widely expressed in human kidney, heart, brain and spleen [25]. MALAT1 locus transcripts are of 2 types: one 6700 bp nucleic (MALAT1) and the other being 61 bp cytoplasmic MALAT1-associated small cytoplasmic RNA (mascRNA) [26]. Wang et al. focused on the interaction between miR-101, miR-217 and MALAT1, demonstrating how this lncRNA can act as a competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNA) sequestering these two miRNAs. MiR-101, miR-217 are involved in regulation of cell cycle; particularly, they inhibit cell cycle by G2/M transition arrest, block cell migration and invasion. Indeed, ESCC tissues showed very high levels of MALAT1 and, conversely, a down-regulation of miR-101 and miR-217 compared to adjacent non-cancerous tissues [27]. Based on previous studies, authors paid attention to one of the most activated pathways in cancer: the Wnt/β-catenin one, which is upregulated in ESCC too. The enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) expression was found significantly higher in ESCC tissue than in normal one. A tested down-regulation of MALAT1 inhibited the expression of EZH2 from mRNA to protein. Therefore, it was proved MALAT1 expression increases the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, via EZH2 [28]. EZH2 is the catalytic subunit of polycomb-group (PcG) proteins complex-2 (PCR2); this complex has histone methyltransferase activity and can epigenetically regulate gene expression. Finally, the same article focused on the prognostic impact of MALAT1 in ESCC. Its expression is associated with stage, lymph-nodes metastasis and to poor overall survival (OS) [28]. These studies confirm the oncogenetic role of MALAT1 in ESCC.

-

−

HOTAIR (HOX Transcript Antisense RNA) is a transcript of ∼2200 bp, located on chromosome 12, initially linked to primary and metastatic breast tumor [29,30]. In ESCC, it is known as an independent prognostic indicator; in fact, its expression is correlated to stage and lymph node metastasis [31]. Ge et al. studies showed an epigenetic activity of HOTAIR in regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Precisely, HOTAIR with its 5′ domain binds to polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), and its 3′ domain binds the LSD1/CoREST/REST complex, coordinating PRC2 and LSD1 to target chromatin, leading to the methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3k27) and to the demethylation of lysine 4 (H3K4), respectively. This chromatin remodeling involves the promoter region of the gene Wnt inhibitory factor-1 (WIF-1) which consequently arrests its expression with the upregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The effects include translocation of β-catenin in the cell nucleus, exerting its transcriptional activity, and the consequent expression of related genes, such as c-Myc and Cyclin D1, which control the G1 to S phase transition in cancer cells [30,32,33]. In addition, a recent genetic study identified a higher risk of developing ESCC in rs920778 TT carriers in HOTAIR gene compared rs920778CC carriers. This allelic regulation clearly demonstrates the key role of HOTAIR in ESCC developing and progression [34].

-

−

ANRIL (Antisense ncRNA in the INK4 locus; also known as CDKN2B-AS1: Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 inhibitor B - antisense RNA 1) is a 3.8 kb lncRNA located within the CDKN2B-CDKN2A gene cluster at chromosome 9p21 [35]. This locus is homozygously deleted or silenced in cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and several types of cancers with a frequency of 30–40%, becoming one of the most frequently altered genes in human malignancies [[36], [37], [38]]. It is overexpressed in gastric cancer (GC) [38], and ESCC [39]. ANRIL silencing blocks cancer cells proliferation in G0-G1 phase and induces cell apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo. ANRIL transcription is induced by ATM-E2F1 signaling pathway [40,41] and acts as an oncogene bot in cis and in trans. Indeed, in cis it can recruit and bind to PRC2 (at its RNA binding domain in subunit: SUZ12) inducing methylation of H3K27 and consequently silencing p15INK4B, which is a tumor suppressor gene [40]; ANRIL can also bind to PRC1 (at its RNA binding domain in subunit: CBX7) silencing the p16INK4A/p14ARF, another important tumor suppressor gene. Furthermore, in trans, by the recruitment of PCR2, it can epigenetically repress the transcription of miR-99a/miR-449a. The well-known targets inhibited by miR-99a/miR-449a are CDK6 and mTOR, both important positive modulators of cell cycle progression. Since p15INK4B and p16INK4A are also inhibitors of CDK6 and mTOR, together this leads to a significant increase expression of CDK6, mTOR, and in a dephosphorylation of RB protein resulting in an overexpression of E2F1 that consequently induces ANRIL expression. In this way, it establishes a positive feedback loop that induces cell cycle deregulation and promotes cancer cells proliferation [38,39]. These results suggest that ANRIL could be a good candidate prognostic biomarker and target for new target therapy.

-

−

H19. This lncRNA can act as either an oncogene or a tumor suppressor gene depending on cancer types. It was initially reported to be upregulated in human breast tumors [42,43]. Also in ESCC patients, a significant upregulation of H19 has been reported; moreover, its level is correlated with higher depth of invasion, neoplastic grading and TNM [44,45]. The functional mechanism of this lncRNA will be further analyzed in the GC section.

-

−

POU3F3 (lnc-POU Class 3 Transcription Factor 3) is located in the chromosome 2q12, near the POU3F3 gene. Li et al. demonstrated a significant overexpression of this lncRNA in ESCC tissues and in vitro this gives a greater ability to form colonies and an up-regulation of the proliferation. An overexpression of lnc-POU3F3 induces the methylation of POU3F3 promoter via EZH2, a key component of PCR2. The main targets of PRC2 are signaling components and transcription factors like the POU transcription factor families. So first, they concluded that there is a connection between lncPOU3F3 and POU3F3 protein, via EZH2 protein. Second, they hypothesized that the conserved-DNA position of lncPOU3F3 is functionally linked to PcG proteins in order to regulate neighbor genes expression altering their methylation [46].

-

−

TUG1 (Taurine up-regulated lncRNA) was first identified in the differentiation process of retinal cells [47]. In 2014 Zhang et al. [48] found that in NSCLC, the expression of TUG1 was significantly down-regulated compared with the normal controls, and its expression was significantly correlated with TNM stage, tumor size and poorer OS. However, in contrast with this discovery, Xu et al. [49] demonstrated an overexpression of TUG1 in ESCC compared with adjacent normal tissue; in addition, the same paper provided clear evidences that silencing TUG1 is possible to inhibit proliferation, migration, and cell cycle. Although the TUG1 molecular mechanism of action is not well elucidated it has been demonstrated that it is activated by p53 and can bind the methylated and un-methylated PRC2 together with MALAT1, regulating homeobox B7 (HOXB7) expression by interacting with EZH2 [50,51]. Regardless, this different behavior may indicate a bifunctional nature of the lncRNA or may be due to the differences of cellular context.

-

−

SOX2-OT (SOX2 overlapping transcript) is located in the 3q26.33 locus and has been demonstrated playing a pivotal role in vertebrate development [52]. SOX2-OT locus overlap, on the third intron, to the single-exon gene SOX2, an important transcriptional factor, that act as pluripotency state modulator. Recently Shahryari et al. [53,54] found an overexpression of SOX2-OT in paired human tumor/non-tumor samples of ESCC and in NTERA2, a human embryonal carcinoma stem cell line. In addition, they found that SOX2 was co-upregulated in tumor samples and the silencing of SOX2-OT deregulates cell cycle. Finally, in ESCC, two novel SOX2-OT spliced variants (SOX2OT-S1 and SOX2OT-S2) were found to be dysregulated and participate in tumor initiation and progression [53]. All of these evidences suggested that SOX2-OT can mutually act with SOX2 and can modulate cancer stemness, but the underlying mechanism of the overexpression of SOX2-OT in ESCC remains to be further discussed.

-

−

UCA1 (Urothelial cancer-associated 1; also known as CUDR: Cancer Upregulated Drug Resistant) is located in 19p13.12 locus and contains three exons encoding two transcripts, one of 1200 bp in length, and other of 2.2 bp; was firstly found upregulated in bladder cancer [55,56] and later in breast cancer [57], tongue squamous cell carcinomas [58], colorectal cancer [59], and ESCC [60]. Jiao et al. [61] showed that UCA1 can compete with SOX4 mRNA for miR-204, an important tumor suppressor miRNA in various cancers, this reduces the binding of miR-204 to SOX4 3′UTR and thereby the miR-204-mediated inhibition of SOX4 is reduced. SOX4 protein is a member of the Sry-related high mobility group box (SOX) family transcription factors and it is involved in apoptosis as well as tumorigenesis and cancer stemness. Other UCA1 downstream targets include cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) [62], p27 (Kip1) [57] and hexokinase 2 (HK2) [60] that modulate a variety of cellular processes including cell cycle and glycolysis. UCA1 silencing results in decreased cell proliferation, migration and invasion ability; whereas higher UCA1 expression correlated with poor differentiation, advanced clinical stage and a poorer prognosis [63].

-

−

CBR3-AS1 (Carbonyl Reductase 3 antisense RNA 1; also known as PlncRNA-1: Prostate Cancer Up-Regulated Long Noncoding RNA 1) is located on chromosome 21 and was found significantly overexpressed in prostate cancer compared with normal tissues and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Silencing CBR3-AS1 through the down-expression of androgen receptor mRNA and protein as well as androgen receptor downstream targets, blocks proliferation and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines [64]. CBR3-AS1 level is significantly higher in human ESCC than in normal tissue and is related with advanced clinical stage, lymph node metastasis; whereas knockdown of CBR3-AS1 could prevent cell proliferation, induce cell apoptosis and promote cycle transit from G1 to S phase [65]. However, the underlying mechanism of PlncrNA-1 function in ESCC remains unknown.

-

−

FOXCUT (LncRNA Fork head box C1 Upstream Transcript) and its adjacent FOXC1 gene are overexpressed in both oral squamous cell carcinoma and ESCC [66,67]. Remarkably, upregulated FOXCUT and FOXC1 expression levels are correlated with poor differentiation, lymph node metastasis and worse prognosis [67]. FOXCUT silencing reduces cell proliferation, migration, invasion and colony formation and the expression of FOXC1 gene, so FOXCUT might modulate FOXC1 mRNA synthesis [68]. However, the mechanism of how FOXCUT interacts with FOXC1 to regulate the ESCC progression is still unclear.

-

−

SPRY4-IT1 (Sprouty 4 intronic transcript 1) is a 708 bp lncRNA located on chromosome 5 and transcribed from the second intron of SPRY4 gene [69]. It is highly expressed in melanoma cells, trophoblast cells, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and ESCC [[70], [71], [72], [73]] and downregulated in NSCLC cancer [74]. In vitro studies demonstrated that SPRY4-IT1 is upregulated in cancer cells, where it is able to increase motility, promote vimentin, fibronectin and SNAIL genes expression; and also a concomitant decrease of E-Cadherin gene expression in order to support the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a critical process for tumor metastasis [75,76]. Furthermore, high expression of SPRY4-IT1 is associated with tumor differentiation, lymph node metastasis and clinical stage rather than patient's gender, smoking status, alcohol consumption and tumor location [77]. These results confirm that SPRY4-IT1 can act as an oncogenic-regulator in ESCC [78].

-

−

CCAT 2 (Colon cancer associated transcript 2), mapped to 8q24.21, is another important lncRNA involved in ESSC tumorigenesis. Its DNA locus is essential, because of its proximity to MYC gene, about 335 kb away, and is often amplified in ESCC. Zhang et al. investigated that MYC and CCAT2 amplification occur simultaneously. MYC overexpression, and consequently CCAT2, induced chromosomal instability and altered DNA replication Since CCAT2 amplification is related to worse clinical outcome (advanced TNM stages and number of metastatic lymph nodes), it has been argued as a prognostic factor in ESCC [79].

-

−

CASC9 (Cancer susceptibility candidate 9), mapped to 8q21.11, is a lncRNA highly expressed in ESCC compared to adjacent normal tissue. Particularly, its expression is higher in poor differentiated carcinomas.CASC9 in vitro inhibition causes an arrest of cell migration and invasion [80].

-

−

CCAT1 (Colon cancer-associated transcript-1; also known as LncRNA CARLo-5) is located at an intergenic region on chromosome 8 and was first identified in colorectal cancer [81]. It is upregulated in ESCC and can recruit EZH2 and SUV39H1; this leads to the epigenetic downregulation of SPRY4, an important tumor suppressor gene [82].

-

−

PCAT-1 (Prostate cancer-associated ncRNA transcript 1) is located in 8q30 and is about 725 kb upstream of the c-Myc oncogene. PCAT-1 interacts with PRC2 and regulate H3K27 methylation [83]. A high expression of PCAT-1 was found in human ESCC and was associated with invasion, lymph node metastasis, advanced pathologic stage and a shorter OS. Therefore, PCAT-1 may be used as a potential diagnostic signature to evaluate ESCC patients prognosis [84].

-

−

PEG10 (lcnRNA Paternally Expressed Gene 10) is a 763 bp long transcript located in chromosome 7. It has been found overexpressed in EC tissues and related to lymph node metastasis. PEG10 silencing inhibits proliferation and invasion and enhance apoptosis in EC cell lines [85]. However, PEG10 role in ESCC remains to be elucidated.

3.1.2. Downregulated lncRNAs

-

−

TUSC7 (Tumor suppressor candidate 7; also known as LSAMP-AS3: LSAMP antisense RNA3 or as lncRNA LOC285194) is a newly identified lncRNA, comprising 4 exons with a length of about 2100 bp and is situated at 3q13.31 locus. TUSC7 is activated by p53 and there is also a mutually repressive interaction between TUSC7 and miR-23b and miR-211 [86,87]. TUSC7 plays a key role in cell growth inhibition through the suppression of miR-23b in GC, colon cancer and osteosarcoma [88]. According to these findings, Tong et al. [86] recently have shown that TUSC7 is downregulated also in ESCC is and can act as a tumor suppressor gene. Moreover, is associated with chemo-radiotherapy resistance; in fact, among patients treated with neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy followed by surgical resection, the rate of pathological complete regression grade was higher in patients with high TUSC7 expression.

-

−

LOC100130476 is located on 6q23.3 and contains 3 CpG islands. Recent studies investigate, its role in ESCC [89] and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (GCA) [90], focusing on the importance of its methylation status. In both studies LOC100130476 is significantly downregulated due to hypermethylation of the CpG sites in exon 1, which is close to the transcription starting site. Conversely, overexpression of LOC100130476 in ESCC cell lines inhibits cell proliferation and reduces invasiveness. Therefore, these results recognize the lncRNA LOC100130476 as a tumor suppressor in ESCC and in GCA.

3.1.3. Other ESCC-related lncRNAs

LincRNA-uc003opf.1 (Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNA 951) is mapped on chromosome 3. Wu et al. in a Chinese population-based study, found the presence of the SNP rs11752942A > G in the exon of this lncRNA. The rs11752942 GG and AG genotypes had a markedly decreased risk of ESCC, compared with the rs11752842AA genotype. The rs11752942G allele could markedly attenuate the level of lincRNA-uc003opf.1 both in vivo and in vitro by binding micro-RNA-149, reducing cell proliferation and tumor growth. Therefore, genetic polymorphism rs11752942A > G in lincRNA-uc003opf.1 exon could be a functional modifier for the development of ESCC [91].

3.2. LncRNAs involved in EAC

EAC is more common in Western and developed countries. The well-known risk factors include gastroesophageal reflux, Barrett's esophagus (via metaplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence), obesity, caucasian race, increasing age, alcohol and smoking. The study of lncRNAs in EAC is not too advanced [92].

In 2013, Wu et al. investigated the role of lncRNA AFAP1-AS1 (Actin Filament Associated Protein 1 – antisense RNA 1) in Barrett's esophagus (BE) and in EAC. This lncRNA is aberrantly hypomethylated in the precursor lesion (BE), compared to normal esophageal and gastric tissues. This epigenetic modification occurs near the AFAP1-AS1 transcription start site and introgenic regions. Furthermore, this aberrant form of lncRNA AFAP1-AS1 has been found to be higher in EAC than in normal tissues. These results were consistent with its level of hypomethylation. These data have no effect on the expression of protein-coding gene AFAP1, a modulator of actin filament integrity. They also tested the effects of inhibition of AFAP1-ASA1 in EAC cell lines. Its silencing reduces cells proliferation and invasion, underlying its oncogenic role in vitro [93].

LncRNA HNF1A-AS1: Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha - antisense RNA 1 is a bidirectional lncrNA. It was found upregulated in human EAC and its silencing reduced cell proliferation, migration, invasion and anchorage-independent growth, induces cell cycle arrest and decreases the expression of H19 [27,94,95]. However, how HNF1A-AS1 regulates other lncRNAs is required to be further investigated.

In 2014, Wang et al. present their work about advanced GCAs and lncRNAs/mRNAs aberrant expression. An average of 2300 lncRNAs and 1700 mRNAs were over-expressed. Particularly, ASHG19A3A028863 and ASHG19A3A031505 were the most up-regulated lncRNA and mRNA, respectively, compared with adjacent non-cancerous tissues. However, this work is only focused on lncRNAs role in GCA carcinogenesis [96].

4. LNCRNAs in gastric cancer

GC is the fifth most common malignancies and one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. GC is the commonest cancer in China. From the histological viewpoint, most GC are adenocarcinomas. Their pathogenesis is based on the step-by-step pathway (i.e. Correa's Cascade) due to risk factors, genetic and epigenetic changes.

Recent studies have investigated and focused on the importance of lncRNAs in this type of cancer. Table 2 summarized and integrate these studies.

Table 2.

Dysregulated lncRNAs in GC.

| EXPRESSION | LncRNA | GENOME LOCATION | CARCINOGENETIC ROLES | TARGETS | MOLECULAR MECHANISMS | CLINICO-PATHOLOGICAL CORRELATIONS | INVESTIGATED MATERIALS | REFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | MALAT1 | 11q13.1 | Proliferation | SF2/ASF, EGFL7, miR-23b-3p | Alternative splicing of SF2/ASF; upregulation of EGFL7 by altering the level of H3 histone acetylation in its promoter; ceRNA for miR-23b-3p, which regulates autophagy associated chemoresistance | Higher plasma level in GC patients with distant metastasis, chemoresistance | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma | [[97], [98], [99],102,226] |

| Upregulated | HOTAIR | 12q13.13 | Proliferation, invasion, motility, EMT, apoptosis | MMP1, MMP3, SNAIL, PARP-1, PCBP1, miR-331-3p, HER2 | Invasiveness and metastasis promotion by modulation of MMP1, MMP3 and PCBP1; EMT promoting by overexpression of SNAIL; apoptosis regulation by modulation of PARP-1; ceRNA for miR-331-3p increasing HER2 expression | Lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, stage, OS, chemoresistance | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [[103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109]] |

| Upregulated | H19 | 11p15.5 | Proliferation apoptosis | P53, BAX, RUNX1, CALN1, ISM1, miR-141, IGFR1, ZEB1 | Activated by c-MYC; p53 inactivation and ISM1 upregulation promote proliferation and endothelial cell survival; BAX suppression inhibits apoptosis; precursor of miR-675-5p, which negatively modulate RUNX1 and CALN1; ceRNAs for miR-141, modulating IGFR1 and ZEB1 expression | OS, higher plasma level in GC patients | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma | [123,125,[128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133]] |

| Upregulated | PVT1 | 8q24.21 | Proliferation, invasion, migration | FOXM1, p15INK4B, p16INK4A, miR-186, HIF-1a | Binds to FOXM1 to inhibit its ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation; p15INK4B and p16INK4A epigenetic silencing by EZH2; ceRNA for miR-186, regulating HIF-1a expression | Stage, lymph node metastasis, DFS, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [[139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145]] |

| Upregulated | GAPLINC | 18p11.31 | Proliferation, angiogenesis, migration | CD44, miR-211-3p | Activated by mutant TP53; ceRNA for miR-211-3p, negatively regulating CD44 and GAPLINC | OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [146,147] |

| Upregulated | GHET1 | 7q36.1 | Proliferation | IGF2BP1 | Bind to IGF2BP1 to increase the stability of c-Myc mRNA and protein translation. | Tumor size, invasion, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [149,151] |

| Upregulated | TINCR | 19p13.3 | Proliferation, invasion, migration, apoptosis | KLF2, CDKN1A/P21, CDKN2B/P15, miR-375, PDK1 | Staufen-mediated post-transcriptional silencing of KLF2, a transcription factor which regulate op21 and p15; ceRNA for miR-375, which regulate PDK1 expression | OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [152,153,227] |

| Upregulated | HULC | 6p24.3 | Autophagy apoptosis, EMT | LC3-I, LC3-II, E-CAD, VIM | Increase E-Cad and decrease vimentin expression; switch to autophagy | Tumor size, lymph node and distant metastasis, distant metastasis, N stage | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [156,228] |

| Upregulated | HOXA11-AS | 7p15.2 | Cell cycle progression, invasion, migration | EZH2, LSD1, DNMT1 | Epigenetic regulation of KLF2 and PRSS8; ceRNA for miR-1297, which regulate EZH2 expression | Distant MTS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [159,229] |

| Upregulated | CCAT1 | 8q24.21 | Proliferation apoptosis, invasion | ERK, MAPK, miR-490, hnRNPA1 | c-Myc binds to CCAT1 promoter promoting its expression; ceRNA for miR-490, which modulate hnRNPA1 expression | Upregulated also in preneoplastic lesions; increased plasma level in GC patients | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma | [161,162,230,231] |

| Upregulated | MRUL | 7q21.12 | Apoptosis, drug resistance | ABCB1 | NA | Chemoresistance | Cell lines | [163] |

| Upregulated | FRLnc1 | 12p13.33 | Migration | TGF-1b, TWIST | Poor information: is modulated by FOXM1 | OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [164] |

| Upregulated | MALAT2 | NA | Migration, EMT | MEK | NA | Lymph node MTS, stage, DFS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [165] |

| Upregulated | BANCR | 9q21.12 | Invasion, migration | miR-9 NF-kb |

CeRNA for miR-9, which regulates NF-kb expression |

Stage, lymph node and distant MTS, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [166] |

| Upregulated | GACAT3 | 2p24.3 | Proliferation | IL6/STAT3 | GACAT3 is a downstream target of the IL6/STAT3 signaling pathway | Tumor size, stage, distant MTS, CEA levels | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [167,168] |

| Upregulated | AK058003 | 10q22 | Migration, invasion, motility | SNCG | Upregulated by hypoxia; epigenetic regulation of SNCG | Depth of invasion, lymph node MTS, vascular invasion | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [169] |

| Upregulated | GClnc1 | 6q25.3 | Proliferation, migration, invasion | WDR5, KAT2A, SOD2 | Scaffold for WDR5/KAT2A complexes, coordinating their localization, and modulating histone modification pattern on target genes, including SOD2 | Differentiation, vascular invasion, tumor size, and stage, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [170] |

| Upregulated | BC032469 | NA | Proliferation, migration | miR-1207-5p, hTERT | CeRNA for miR-1207-5p, which regulates hTERT | Tumor size, differentiation, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [150] |

| Upregulated | LINC00152 | 2p11.2 | Proliferation, migration invasion, apoptosis, EMT, | EFGR, miR-193a-3p, MCL1, P15, P21, EZH2 | Bind to EGFR causing PI3K/AKT signaling activation; ceRNA for miR-193a-3p, which regulates MCL1 expression; epigenetic regulation of p15 and p21 via EZH2 | Higher level in plasma and gastric juice of GC patients, tumor volume, tumor invasion depth, stage, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma, gastric juice | [171,[232], [233], [234], [235]] |

| Upregulated | UCA1 | 19p13.12 | Proliferation, invasion, migration, apoptosis, EMT | miR-7-5p, EGFR, miR-590-3p, CREB1, PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway, GRK2, ERK-MMP9 signaling pathway, AKT/GSK-3B/cyclin D1axis, TGFβ1, miR-27b, PARP, BCL-2 | CeRNA for miR-7-5p (which regulates EGFR) and miR-590-3p (which regulates CREB); upregulation of AKT3, p-AKT3, p-mTOR, and S6K, and inhibited the expression of EIF4E; degradation of GRK2 protein through Cbl-c-mediated ubiquitination, which results in the activation of the ERK-MMP9 signaling pathway; activation of AKT/GSK-3B/cyclin D1 axis; promotion of TGFβ1-induced EMT; Increases MDR downregulating miR-27b, cleaved PARP protein and upregulating Bcl-2 expression | Higher level in gastric juice of GC patients, differentiation, tumor size, invasion depth, lymph node MTS, stage, OS, multidrug resistance | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma, gastric juice | [[236], [237], [238], [239], [240], [241], [242], [243]] |

| Upregulated | ANRIL | 9p21.3 | Proliferation | miR-99a/miR-449a, CDK6, mTOR, E2F1, TET2, p15, p16, | Increase CDK6, mTOR and E2F1 expression through epigenetic silencing of miR-99a/miR-449a; TET2 (downregulated in GC) modulates ANRIL expression binding to its promoter region | Stage, tumor size, multidrug resistance, OS, DFS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [35,38,40] [244,245] |

| Downregulated | GAS5 | 1q25.1 | Proliferation, apoptosis | E2F1, Cyclin D1, YBX1, p21, miR-22, PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathway, CDK6 | CeRNA for miR-222 (increasing PTEN and decreasing p-Akt p-mTOR levels), miR-23a (increasing MT2A levels); GAS5 upregulates YBX1, which increase p21 expression; inhibition of CDK6 | OS, chemoresistance | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [181,182,[246], [247], [248], [249]] |

| Downregulated | MEG3 | 14q32.2 | Proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, angiogenesis, EMT, migration | P53, miR-181a, BCL2, E2F3, miR-141, Notch, RB, VEGF, MMP3, MMP9, GDF15, miR-21 | miR-148a increases MEG3 expression reducing methylation status of its regulatory regions; MiR-208a silencing MEG3; ceRNA miR-181a, which regulates BCL-2; correlated with miR-141 and inversely correlated with E2F3; regulates Notch, Rb, VEGF, MMP3, MMP9 and GDF15 expression; downregulates miR-21 | Stage, depth of invasion, OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [183, [189], [190], [191], [192], 250, 251] |

| Downregulated | FER1L4 | 20q11.22 | Proliferation | miR-106a-5p, PTEN | CeRNA for miR-106a-5p, which regulates PTEN | Histological grade, tumor size, stage, lymph node MTS, perineural and vascular invasion: plasma levels declines after surgery | Cell lines, human tissue samples, plasma | [[193], [194], [195]] |

| Downregulated | FENDRR | 16q24.1 | Differentiation, proliferation, migration | PRC2, FN1, MMP2, MMP9 | Poor information: its levels are negatively correlated with FN1 and MMP2/MMP9 expression | OS, DFS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [197] |

| Downregulated | BM742401 | 18q11.2 | Migration | MMP9 | Decrease MMP9 extracellular secretion | OS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [198] |

| Downregulated | PTENP1 | 9p13.3 | Proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion | miR-106b, miR-93, PTEN | CeRNA for miR-106b and miR-93, which regulate PTEN | Tumor size, stage, depth of invasion depth, lymph node MTS | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [200,201] |

| Downregulated | TUSC7 | 3q13.31 | Proliferation | miR-23b, PDCD4 | CeRNA for miR-23b, which regulates PDCD4 | DFS, chemoresistance | Cell lines, human tissue samples | [88] |

4.1. Upregulated lncRNAs

-

−

MALAT-1, is one of most studied lncRNA because of his pivotal role in different types of cancer; we have extensively talked about this lcnRNA in the ESCC section, here we add more information about its potential acting mechanism in GC pathogenesis. Different studies demonstrate that MALAT-1 acts as an oncogene in GC; in fact, its depletion inhibits cell proliferation, cell cycle, cell migration, and promotes apoptosis. Recently Xia et al. investigate the relationship between MALAT-1 and miRNA-122, discovering how miR-122 modulates the MALAT-1 expression in a negative way. Its levels result higher in GC tissues and in distant metastasis, than those in normal tissues. MALAT1 is also detectable in plasma and its high concentration are consistent with the tissue data. Particularly, patients without distant metastasis show lower plasmatic levels than patients with distant metastasis, though authors hadn't found any difference between patients with GC without metastasis and healthy controls [97,98]. Wang et al. proved that MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by interaction with the serine/arginine-rich family of nuclear phosphoproteins [25,[99], [100], [101]]. SF2/ASF is an important member of this family and it is involved in multiple human cancers [101]. Authors demonstrated that an in vitro downregulation of SF2/ASF or MALAT1 provoked cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase. These findings indicate that MALAT1 may stimulate proliferation of GC cells partly through mediating SF2/ASF [102]. All these evidences demonstrate that MALAT1 is a critical promoter in GC cells and might be an oncogene in human GC.

-

−

HOTAIR: In GC, HOTAIR shows elevated levels in GC cell lines and tissues compared to normal gastric ones. Lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis and TNM stages and lower OS rate are linked to the HOTAIR overexpression in vitro and in vivo [[103], [104], [105]]. Experiments of knockdown HOTAIR expression in cancer cell lines show: (i) inhibition of cell proliferation in G0-G1 phase through a cooperative expression and action between HOTAIR and SUZ12 (a member of PRC2) which could affect the epigenetic status of cancer-associated genes [104]; (ii) reduction of invasiveness and motility, through the regulation of metalloproteinase (MMP) 1 and 3 [68]; (iii)reversion the EMT trough miR34a-mediated SNAIL expression inhibition [106]; (iv) finally, reveal its role in apoptotic pathway, since it can activate cleaved PARP-1, an enzyme involved in DNA repair. In addition, HOTAIR could promote metastasis through suppression of Poly(rC)-Binding Protein 1 (PCBP1) [107] and is also involved in HER2 overexpression [106]. HER2 is an oncogene and its overexpression is associated with poor OS [108]. HER2 is downregulated by miR-331-3p. In this pathway HOTAIR can act as ceRNA (a sort of endogenous sponge) that directly bind to miR-331-3p, thus abolishing the miRNA-induced repressing activity on the HER2 3′-UTR. Finally, a recent study investigates the effect of HOTAIR on patients receiving chemotherapy (fluorouracil and platinum) and its overexpression is correlated to advanced stages, poor median survival time and chemo-resistance [109]. All these results underline the oncogenic role of HOTAIR in GC and highlight his potential role as a potential predictive biomarker and a novel target for HER2 positive patients.

-

−

H19 gene is located on locus 11p15.5, near the insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) gene; it codes for a 2300 bp lncRNA and is highly expressed during embryogenesis, but its expression is reduced after birth [[110], [111], [112], [113]]. This gene is only expressed from the maternally-inherited chromosome, whereas IGF2 is only expressed from the paternally-inherited chromosome; both are regulated by the differentially methylated region (DMR) or the imprinting control region (ICR) located 4 kb upstream of the H19 gene [114]. Dysregulation of H19 expression is observed in many types of cancer, including esophageal, liver, cervical, bladder, lung, and breast cancer [94,[115], [116], [117], [118], [119]]; however, H19 could play different roles depending on the tissue type. Indeed, in some tumors, it can act as a tumor suppressor gene [95,120], but more often, possesses oncogenic ability [43,[121], [122], [123]]. In GC H19 was shown to be upregulated relative to normal adjacent tissues, as well as in human GC cell lines compared to the normal gastric epithelial cell lines [18,[124], [125], [126], [127]]. H19 overexpression induces GC cells proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by partly inactivating p53 and suppressing the expression of the B-cell lymphoma-associated X protein (BAX), a p53 target. H19 expression is induced by c-Myc, another oncogene, which regulates itself GC cells proliferation [123,128]. Furthermore, H19 is the precursor of miR-675-5p [124]. Both are overexpressed in GC tissue and miR-675-5p promotes cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. MiR-675 targets are Runt domain transcription factor1 (RUNX1) and Calneuron 1 (CALN1), two tumor suppressor genes, which are both downregulated in GC. In addition, H19 regulates directly isthmin (ISM)1, a factor promoting endothelial cell survival [63,129,130]. Finally, H19 in GC can act also as ceRNAs with miR-141. In fact, H19 and miR-141 levels are inversely correlated in GC. In this way H19 can modulate the expression of target genes like IGF-2, IGF Receptor 1 (IGFR1), and Zinc finger E-box-Binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) [131]. It denotes how, through different mechanisms, H19 can modulate the expression of multiple genes, promoting cellular proliferation, invasion and migration [129]. From a clinical point of view H19 over-expression is correlated with poor prognosis and to a shorter survival time of GC patients [128,129]. H19 plasma levels observed to be higher in GC patients than in healthy controls, and conversely postoperative plasma level is decreased compared to the preoperative ones [132,133]. Therefore, H19 could be a good and reliable biological marker that can be used as prognosis predictor and in follow-up serological exams.

-

−

PVT1 (Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 lncRNA) has been mapped to 8q24 and its copy-number amplification is one of the most frequent events in a wide variety of cancers, including GC [[134], [135], [136], [137], [138]]. It seems to have different acting mechanisms. Xu and colleagues demonstrated that the PVT1 promoter contains a binding site for the transcriptional factor Forkhead Box M1 (FOXM1). PVT1 bind to FOXM1 protein to increase its stabilization, inhibit its ubiquitin/26s proteasome-mediated degradation. Contrarily, high level of FOXM1 induces PVT1 overexpression. This positive feedback loop promotes GC cells proliferation and metastasis [139]. Furthermore, PVT1 is involved in epigenetic downregulation of p15INK4B and p16INK4A through EZH2, promoting GC cells proliferation [139]. Finally, Huang et al. [140] have demonstrated that PVT1 can “sponging” miR-186 and in this way can reduce the inhibition of Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression in GC cells. HIF-1α is a key transcription factor promoting cancer development and tumor progression and its overexpression is driven by the intratumoral hypoxia and genetic alterations regarding other oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [139,[141], [142], [143]]. In GC, HIF-1α overexpression correlated with tumor stage and lymph node metastasis, poor OS and DFS in post-gastrectomy patients [139,144,145]. Thus, these data suggest that PVT1 can act as an oncogene and the inhibition of HIF-1α could represent a novel approach to cancer targeted-therapy.

-

−

GAPLINC (Gastric Adenocarcinoma-associated Positive cluster of differentiation 44 regulator Long Intergenic Non-Coding RNA) is a 924 bp lncRNA overexpressed in GC and is associated with increased proliferation and with CD44-dependent oncogenesis, both in vitro and in vivo [146,147]. CD44, is a well-known oncogene involved in proliferation, angiogenesis and migration of GC cells [148]. GAPLINC is activated by mutant p53 and a strong correlation between GAPLINC and CD44 expression was reported; noteworthy, CD44 silencing was proved to neutralize oncogenic functions of GAPLINC. So, Hu et al. [146] showed that GAPLINC can act as a ‘miRNA sponges’ that prevents CD44-mRNA degradation by competing for the binding with miRNA 211-3p. In fact, GAPLINC and CD44 are both negatively modulate by miR-211-3p. In addition, GAPLINC levels are associated with patients' survival, supporting its role as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for GC patients and as a potential therapeutic target [146].

-

−

GHET1 (Gastric carcinoma High Expressed Transcript 1) which is located in an intergenic region on chromosome 7 in the locus 7q36.1. By primary screen of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs in GC Yang et al. showed that GHET1 is significantly overexpressed in GC patients tissue compared to healthy controls. Gain-of-function experiments have demonstrated that overexpression of GHET1 promotes the proliferation of GC cells, while knockdown of GHET1 inhibits the proliferation of GC cells [149,150]. From the molecular point of view, GHET1 could bind to insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) enhancing the physical interaction between c-Myc mRNA and IGF2BP1 and consequently increasing the stability of c-Myc mRNA and its protein translation. Finally, c-Myc overexpression promotes GC cells proliferation [151]. GHET1 and c-Myc levels in GC tissues are significantly correlated and c-Myc knockdown blocks the oncogenic effects of GHET1 in GC cell lines [151]. GHET1 overexpression is significantly correlated with tumor size and invasion, as well as patients' outcome [151].

-

−

TINCR (Terminal Differentiation-Induced ncRNA) is a 3700 bp lncRNA that controls human epidermal differentiation. LncRNAs can regulate genes expression at the post-transcriptional level by directly interacting with mRNAs. The interaction between mRNA and the complementary lncRNA, form a dsRNA. Staufen 1 (STAU1) protein recognizes the dsRNA binding sites and this results in mRNA degradation. This process is called STAU1-mediated mRNA decay (SMD) [152,153]. For instance, TINCR, whose expression is modulated by the nuclear transcription factor SP1, interact with Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) mRNA forming a dsRNA, STAU1 bind to this complex decreasing KLF2 mRNA stability, inhibiting its protein translation. The post-transcriptional silencing of KLF2 gene downregulates the cell cycle inhibitory genes CDKN1A/P21 and CDKN2B/P15, promoting cancer cells proliferation, migration, invasion and tumorigenicity, which are inhibited if TINCR is silenced [153].

-

−

HULC (Highly Upregulated in Liver Cancer) is a lncRNA firstly identified in hepatocellular carcinoma. In further studies, was found upregulated in other cancers, including pancreatic cancer and GC [[154], [155], [156]]. HULC may be involved in a switch mechanism between apoptosis and autophagy in vitro. Apoptosis and autophagy are two components of programmed cell death and have been associated with a number of physiological processes, including cancer [157,158]. However, autophagy has been shown to have a dual role in cancer progression [158]. Mechanistically, HULC overexpression increases the ratio between microtubule-associated protein 1 Light Chain 3-II (LC3-II) and LC3-I; LC3-II is the product of proteolytic maturation of LC3-I and is the marker for the presence of autophagosomes and the proof of the autophagy activation process. Notably, deletion of HULC expression, in the same GC cell line, induces biochemical (increased expression of E-cadherin, decreased expression of vimentin, and switching to apoptosis) and morphological (different growth pattern and decreased formation of lamellipodia) changes that lead to a reversion of EMT. In addition, the expression levels of HULC correlate with GC lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis and TNM stages [156].

-

−

HOXA11-AS (Homeobox A11-Antisense non-coding RNA) was found upregulated in GC and in vitro and in vivo assays revealed its potential modulation role in cell growth, migration, invasion, and apoptosis. HOXA11-AS can act as a scaffold binding EZH2 and histone demethylase LSD1 or DNMT1 in order to epigenetically reduce KLF2 and PRSS8 expression at the transcriptional level. In addition, can act as a ceRNA for miR-1297, antagonizing its ability to repress EZH2 protein translation [159].

-

−

CCAT1 is overexpressed in several GC cell lines [160,161]. Its knockdown inhibits proliferation by inducing apoptosis and G0/G1 arrest. CCAT1 can modulate the expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-associated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) [162]. In addition, has been observed a correlation between CCAT1 and c-Myc mRNA expression; in fact, c-Myc binds to CCAT1 promoter inducing its expression [160]. Finally, Mizrahi et al. have reported that there are no significant differences in CCAT1 expression between H. pylori-negative and -positive patients, indicating that CCAT dysregulation is a late event in gastric cancerogenic cascade [161].

-

−

MRUL (MDR-Related and Upregulated lncRNA) has been reported to be significantly in vitro overexpressed, and knockdown of MRUL could induce apoptosis and reduce drug release in the presence of adriamycin or vincristine; this mechanism may be mediated by the regulation of ATP-binding cassette, subfamily B, member 1 (ABCB1) expression [163].

-

−

FRLnc1: Forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) Related LncRNA is modulated by FOXM1, a well-known and studied oncogene. In vivo overexpression revealed its role in pulmonary metastasis. In fact, FRLnc1 can regulate the expression of transforming growth factor 1β (TGF-1β) and Twist promoting cell migration and distant tumor metastasis [164].

-

−

MALAT2 overexpression in GC tissues is correlated with lymph node metastasis and tumor stage, as well as with shorter DFS. It can regulate EMT through an MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent mechanism [165].

-

−

BANCR (BRAF-activated ncRNA) was firstly identified as an oncogene in melanoma. Recent studies have also demonstrated that its levels are higher in GC than in normal adjacent tissue; it can act as a ceRNA reducing the level of miRNA-9 and consequently increasing the expression of NF-kβ. Its overexpression is significantly associated with clinical stage, tumor invasiveness, lymph node and distant metastasis and with shorter OS in GC patients [166].

-

−

GACAT3 (also known as AC130710) is upregulated in GC, and its expression levels are associated with tumor size, TNM stage, distant metastasis, and tissue carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) expression level. Shen et al. have demonstrated that as a downstream target of the IL6/STAT3 signaling, lncRNA GACAT3 promotes GC cells growth, and according to this finding, GACAT3 could be an inflammatory response gene [167,168].

-

−

LncRNA AK058003 is upregulated by hypoxia and is overexpressed in GC tissues; its in vitro knockdown suppresses cell migration, invasion, and motility and its in vivo downregulation is linked to a decrease in the number and size of lung and liver metastatic nodules. AK058003 can regulate the expression of Synuclein-γ (SNCG), a metastasis-related gene, that is upregulated also by hypoxia; in fact, it is basically an effector of hypoxia-induced GC metastasis, whereas loss of AK058003 decreases SNCG expression via methylation of its promoter [169].

-

−

GClnc1 (Gastric Cancer–associated lncRNA 1) is significantly overexpressed in GC. GClnc1 binds to WDR5 and KAT2A histone acetyltransferase, acting as a scaffold for WDR5 and KAT2A complexes, coordinating their localization and consequently altering GC cells proliferation, migration and invasion [170].

-

−

LncRNA BC032469 overexpression was positively associated with hTERT level and significantly promotes GC cell proliferation and metastasis. BC032469 can function as ceRNA directly binding to miR-1207-5p and reducing its inhibitory effect on hTERT expression, whose overexpression enhances cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [150].

-

−

LncRNA LINC00152 (Long Intergenic Non-protein-Coding RNA 152) is overexpressed in GC tissues [171,172]. Recent studies have demonstrated that also plasma and gastric juice levels of LINC00152 are significantly higher in GC patients compared with healthy controls, therefore it could be a potential promising noninvasive biomarker for GC screening [20,171]. However, the function of LINC00152 in GC should be further investigated.

-

−

As for ESCC lncRNAs UCA1 and ANRIL are involved in GC carcinogenetic process and acting in a similar manner (see ESCC section). In addition, UCA1 levels in gastric juice are higher in GC patients than in normal individuals, so UCA1 may represent a powerful prognostic marker [63,173] while ANRIL overexpression is significantly correlated with a higher TNM stage, tumor size and shorter OS time [174].

-

−

HIF1A-AS2 (HIF1A Antisense RNA 2), SUMO1P3 (Small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 pseudogene 3), ABHD11-AS1 (Abhydrolase Domain Containing 11- Antisense transcript 1), UBC1 (E2 ubiquitin-conjugated protein 1), LSINCT-5 (Long stress-induced noncoding transcript 5) and RP11-119F7.4 are overexpressed in GC and most of them are significantly correlated with poor prognosis, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, differentiation and TNM stage [144,165,175,176]; however further investigation are needed to deeply elucidate their molecular mechanism.

4.2. Downregulated lncRNAs

-

−

GAS5 (Growth Arrest-Specific transcript 5) is an approximately 650 bp lncRNA and was first found among a screen for potential tumor suppressor genes with high expression during cancer cells growth arrest [177]. GAS5 was identified downregulated in various cancer types such as breast, prostate cancer and GC [[178], [179], [180]]. Its overexpression inhibits cell proliferation and promotes caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in vivo and in vitro, conversely knockdown of GAS5 is associated with larger tumor size, advanced pathologic stage, poorer DFS and OS [181,181]. GAS5 downregulation results in overexpression of E2F1 and cyclin D1, which induces tumorigenesis by stimulating cell proliferation and repressing p21 expression, an inhibitory modulator of the cell cycle [181,182]. These data suggest that GAS5 may act as a tumor suppressor through the post-transcriptional regulation of E2F1 and p21.

-

−

MEG3 (Maternally Expressed Gene 3) is an imprinted gene on human chromosome 14q32.3 that encodes for a lncRNA [183]. MEG3 downregulation occurring in multiple cancers such as glioma, bladder cancer, and tongue squamous cell carcinoma [[184], [185], [186]]. In GC, MEG3 expression is significantly downregulated than in adjacent normal tissue, and its downregulation correlates with higher TNM stage, deeper invasion and larger tumor size. MEG3 acts as a tumor suppressor inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis through the activation of p53 [187,188]. MEG3 is epigenetically modulated by miR-148a that downregulate DNA methyltransferase-1 and consequently reduce the methylation status of the MEG3 regulatory regions (MEG3-DMRs) [189,190]. MEG3 can also act as a ceRNA by competitively binding miR-181a to regulate Bcl-2 and inhibit cell proliferation [191]. In addition, MEG3 is positively correlated with miR-141 and inversely correlated with E2F3 [192] regulating cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and angiogenesis by interacting with Notch, Rb, VEGF, and growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) [183].

-

−

FER1L4 (FER-1-Like protein 4) is a newly identified lncRNA and it is significantly down-regulated in GC tissues [193]; low expression levels of FER1L4 are associated with histological grade, tumor size, TNM stage, lymphatic metastasis, perineural invasion, venous invasion, and CA724 serum levels. Furthermore, its plasma level declines, two weeks after surgery, suggesting that FER1L4 might serve as a biomarker for biochemical evaluations after surgery [194]. In addition, more recent studies suggested that FER1L4 could also act as ceRNA. In fact, FER1L4 levels are correlated with those of PTEN mRNA; both of these tumor suppressor genes are negatively modulated by miR-106a-5p, a well-known onco-miRNA; FER1L4 in vitro downregulation frees miR-106a-5p decreasing the levels of PTEN mRNA and protein. More importantly, FER1L4 downregulation accelerates cell proliferation by promoting the G0/G1 to S phase transition [195]. However, the mechanism and function of FER1L4 should be further explored.

-

−

FENDRR (FOXF1 adjacent Non-coding Developmental Regulatory RNA) is an antisense transcript of 1250 bp located on chromosome 16q24.1, plays an important role in mouse embryogenesis. FENDRR modulates chromatin remodeling by binding to both PRC2 and Trithorax group/Mixed lineage leukemia complexes (TrxG/MLL) [196]. FENDRR is downregulated in GC and its low levels are negatively correlated with fibronectin (FN)1 and MMP2/MMP9 expression indicating that FENDRR is a mediator of cell differentiation, growth, and migration and of GC progression and metastasis [197]. FENDRR expression level is significantly correlated with tumor stage, lymphatic metastasis and OS and DFS of GC patients [197].

-

−

BM742401 is downregulated in GC and its overexpression inhibits the migration and invasion in vitro, while in vivo suppresses metastasis decreasing the secretion of extracellular MMP9 [198].

-

−

GACAT2 (Gastric cancer-associated transcript 2, also known as HMlincRNA717), is downregulated in GC in vivo and in vitro. Its expression was found to be associated with distant metastasis and venous and perineural invasion. GACAT2 is also downregulated in gastric precancerous lesions, suggesting its pivotal role during early stage of GC [168,199].

-

−

PTENP1 (Phosphatase and TENsin homolog - Pseudogene 1) increases PTEN expression by binding to miRNAs (miR-106b and miR-93) reducing their negative modulation of PTEN expression [200,201].

-

−

GACAT1 (Gastric cancer-associated transcript 1, also known as AC096655.1–002), ncRuPAR (Non-Coding RNA, Upstream protease-activated receptor-1(PAR1)), ZMAT1 transcript variant 2 (Zinc Finger Matrin-Type 1 transcript variant 2), LET (Low Expression in Tumor), AI364715 and AC138128.1 have been shown to be downregulated in GC and most of them significantly correlate with OS tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, and TNM stage [165,[202], [203], [204], [205], [206]]; however their molecular mechanisms are still unknown and further investigation are needed.

4.3. Other GC-related lncRNAs

Some lncRNAs have been shown to be dysregulated in GC but until now we have only contrasting and partial data about them. For instance: lncRNA SPRY4-IT expression and function in GC remain a controversial subject. Xie et al. [207] found that SPRY4-IT1 is downregulated in GC and represses cell proliferation in vitro and tumorigenesis in vivo. However, Peng et al. [208] found that SPRY4-IT1 is significantly overexpressed in GC tissues. This shows how the SPRY4-IT1 acting mechanisms are still unknown. Another example is LncRNA AA174084: its levels in the gastric juice of GC patients are higher than controls (with normal mucosa, gastritis, ulcers or atrophic gastritis). These levels are associated with tumor size, tumor stage, histological type, and gastric juice CEA levels. In addition, plasma levels significantly decline postoperatively compared with preoperative levels in GC patients; this reduction is associated with invasion and lymphatic metastasis, while high postoperative plasma AA174084 levels are linked to poor prognosis. However, AA174084 expression is lower in GC tissues than in control and these levels are negatively associated with age, Borrmann type, and perineural invasion. Hence, despite this discrepancy (downregulation in GC tissue and high level in gastric juice GC patients), AA174084 could be a reliable biomarker for early diagnosis and for prognosis prediction [209].

5. Discussion

GC and EC are two of the most common and deadly malignancies worldwide; in particular, they are the fifth and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths respectively; despite the huge therapeutic improvements, their 5-year survival rates are still very poor also due to delayed diagnosis and the lack of deep understanding of their complex pathogenesis.

GC and EC are usually classified into different morphological subtypes according to different systems. However, these classifications are not able enough to guide clinical management and stratify patients in reliable different prognostic groups.

In recent years the molecular landscape of these cancers has gained attention, also because it could bring to novel treatment strategies and to an early stage diagnosis when lesions are too small to be accurately detected using imaging modalities.

Considering that only 2% of the whole genome generates protein-coding transcripts is obvious how we have to elucidate and focus on the complex modulating role of the 98% non-coding genome. In this novel context take place lncRNAs, defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with no protein-coding capacity. They play heterogenous and pivotal roles in main oncogenic processes as cell proliferation, cell cycle, differentiation, programmed cell death, EMT, invasion and migration. LncRNAs can act at various levels exerting different functions: (i) at epigenetic level they can recruit chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genomic loci, can cause methylation of specific genes promoters, silencing their transcription or can cause histone acetylation, promoting the expression of targeted genes; (ii) at transcriptional level they can regulate transcription factors activity; (iii) at post-transcriptional level they can modulate pre-mRNAs splicing process, can function as a ceRNA interfering with miRNAs-mediated genes expression, can interfere in post-translational proteins modification, or can act as molecular scaffolds participating as a structural component in the assembling of multimeric molecular complexes; (iv) in addition, they can generate endogenous small interfering RNAs, which are small single- or double-stranded RNAs that bind to specific target RNAs facilitating their degradation; (v) otherwise some lncRNAs can generate small RNAs, such as miRNAs, piRNAs, or other less characterized small RNAs; (vi) finally, SNPs in lncRNA can modify the basal risk to develop malignancies as for most genes involved in tumorigenesis.

5.1. LncRNAs’ clinical relevance

To date, a large number of lncRNAs have been identified and growing efforts have been made in studying their biological functions in different human cancers. However, many key questions remain unsolved. In fact, in contrast to mRNAs and proteins, their function cannot simply be described according to their structure or sequence because of their complex interacting network and diversity. However, from a statistical viewpoint growing evidences suggest that lncRNAs dysregulation correlates with main oncogenic processes (invasiveness, lymphatic and distant metastasis, differentiation) as well as with overall and disease-free survivals.

Therefore, lncRNAs could represent prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers. Indeed, lncRNAs: (i) have a quite restricted tissue-specific expression, therefore they have a high specificity; (ii) play a key role in the initiation, development, and progression of cancer and their expression levels differ during the different stages, so could be of value to distinguish among patients with cancer in a very early stage (still not detectable using imaging modalities) from healthy individuals; (iii) aberrant expression of cancer-specific lncRNAs can be detected also in body fluids, including plasma or serum, gastric juice, saliva, cerebrospinal/peritoneal/pleural fluid and urine, so it is a noninvasive assessment and could be repeated at different time points; (iv) it is also possible to combine several lncRNAs expression levels (or lncRNAs levels with other transcripts levels or with other biomarkers) in order to obtain a reliable molecular signature that could have a diagnostic and prognostic value. For instance, Dong et al. found that among 39 cancer-related lncRNAs UCA1, LSINCT-5 and PTENP1 are the most significantly downregulated lncRNAs in GC patients compared with the control group; therefore, the assessment of their combination is enough sensitive and specific to distinguish benign peptic ulcers from GC patients and lower expression level is linked to worse survival rates [20,210].

There is also a downside. In fact, we have to better understand how lncRNAs are released into body fluids because circulating lncRNAs is unstable in presence of high amount of RNase in peripheral blood, so they may be packaged into various types of extracellular vesicles (EVs) or could be modified (methylation, adenylation and uridylation) to prevent RNase digestion.

EVs are categorized according their size and origins as: (i) exosomes (small bilayered EVs with 30–100 nm diameter derived from intracellular budding from multivesicular bodies which are formed by endosomes membrane) [211]; (ii) microvesicles (100–1000 nm directly shed from the cellular plasma membrane); (iii) apoptotic bodies (500–4000 nm vesicles derived from cell lysis during the late stages of programmed cell death) [212,213]. EVs can contain: lipids (in their membranes), proteins, coding and non-coding RNAs and DNA fragments [211] coming from neoplastic cells o virus-infected cells [214]. In cancer progression EVs role is crucial; in fact they could act as intercellular communicative vectors facilitating the carcinogenetic and the metastatic processes by transferring these key biological molecules; indeed, in this way also the microenvironment can be modified in order to prepare the dissemination [215].

The mechanism underlying lncRNAs secretion has not been deeply elucidated as for miRNAs but could be very similar, namely through tetraspanins-positive (CD9, CD63,CD81,CD82) exosomes via a ceramide-dependent pathway but without ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) machinery [216].

In recent studies, circulating lncRNAs with a strong clinico-pathological valence have been detected in exosomes both in GC patients (LINC00152, ZFAS1) [20,[217], [218], [219]] and in ESCC ones (PART1) [220].

ZFAS1 overexpression has been found in GC cell lines, tumor tissues, serum and serum exosomes of GC patients and its levels are related to lymphatic metastasis and TNM stage. Moreover, in vitro has been proved that ZFAS1, transmitted through exosomes, could enhance the proliferation and migration of GC cells [219].

Whereas PART1 overexpression promotes gefitinib resistance by regulating miR-129/Bcl-2 pathway in ESCC patients [220].

However, this is only the starting point, further studies are needed to better elucidate the biological roles of this intercellular interaction and lots of technical problems have to be solved before the routinely use of EVs content as reliable biomarker.

Another important challenge could be the use of the amplification to resolve the measurement of lncRNAs low levels in body fluids. To date, to quantify gene expression is widely used qRT-PCR but for lncRNAs selecting the appropriate reference genes is extremely critical but is essential to minimize inter-procedure bias and implement quality control in clinical laboratories. Finally, we have to take in account that EC and GC are heterogeneous diseases that encompass different histologic subtypes with different and often overlapped risk factors, different therapy strategies as well as different prognosis; therefore, despite the lncRNAs tissue-specificity, is necessary to correlate their expression levels with all these important variables.

Hence, large cohort studies are still needed to confirm diagnostic and prognostic sensitivity and specificity of certain lncRNAs in gastroesophageal malignancies.

5.2. Future perspectives

Apart from being biomarkers, lncRNAs may also provide important insights for novel targets therapy; they have tissue- and cancer-specific expression so could be the ideal therapeutic agents.

Recently high-throughput sequencing technologies are even more elucidating the complex interaction network between lncRNAs, DNA, miRNAs, mRNAs and proteins providing novel possible target treatments. At present, siRNAs, antisense oligonucleotides, miRNAs as well as ribozymes or deoxyribozymes, can be designed to silence endogenous lncRNAs. Conversely, synthetically modified lncRNA mimics or plasmid delivery may be used to bring beneficial lncRNAs in vivo.

However, there are still unsolved technical barriers including relative large size, complex secondary structure and possible degradation by nucleases; these problems could affect design, synthesis and delivery of functional therapeutic agents to targeted sites. Furthermore, given the complex and poorly understood interaction networks between lncRNA and other genes, silencing any lncRNA might have unknown physiological responses.

Although lncRNA-based therapeutic drugs are still in preclinical studies, their use seems very promising.

6. Conclusions

In summary, the future of the cancer research will be focused on the non-coding fraction of the genome. Although we are still trying to elucidate the complex network that links together lncRNAs, miRNAs, other non-coding transcripts, mRNAs, proteins and DNA the current findings have shown how we are on the right path; indeed, lncRNAs could firstly represent reliable biomarkers (sensible, significant, early) and in a next future a possible target for developing new therapies.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Acknowledgments

All authors took part in writing the manuscript and approved the final, submitted version.

References

- 1.Djebali S., Davis C.A., Merkel A., Dobin A., Lassmann T., Mortazavi A., Tanzer A., Lagarde J., Lin W., Schlesinger F., Xue C., Marinov G.K., Khatun J., Williams B.A., Zaleski C., Rozowsky J., Roder M., Kokocinski F., Abdelhamid R.F., Alioto T., Antoshechkin I., Baer M.T., Bar N.S., Batut P., Bell K., Bell I., Chakrabortty S., Chen X., Chrast J., Curado J., Derrien T., Drenkow J., Dumais E., Dumais J., Duttagupta R., Falconnet E., Fastuca M., Fejes-Toth K., Ferreira P., Foissac S., Fullwood M.J., Gao H., Gonzalez D., Gordon A., Gunawardena H., Howald C., Jha S., Johnson R., Kapranov P., King B., Kingswood C., Luo O.J., Park E., Persaud K., Preall J.B., Ribeca P., Risk B., Robyr D., Sammeth M., Schaffer L., See L.H., Shahab A., Skancke J., Suzuki A.M., Takahashi H., Tilgner H., Trout D., Walters N., Wang H., Wrobel J., Yu Y., Ruan X., Hayashizaki Y., Harrow J., Gerstein M., Hubbard T., Reymond A., Antonarakis S.E., Hannon G., Giddings M.C., Ruan Y., Wold B., Carninci P., Guigo R., Gingeras T.R. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489(7414):101–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heintzman N.D., Stuart R.K., Hon G., Fu Y., Ching C.W., Hawkins R.D., Barrera L.O., Van Calcar S., Qu C., Ching K.A., Wang W., Weng Z., Green R.D., Crawford G.E., Ren B. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2007;39(3):311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ørom U.A., Derrien T., Beringer M., Gumireddy K., Gardini A., Bussotti G., Lai F., Zytnicki M., Notredame C., Huang Q., Guigo R., Shiekhattar R. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell. 2010;143(1):46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bejerano G., Pheasant M., Makunin I., Stephen S., Kent W.J., Mattick J.S., Haussler D. Ultraconserved elements in the human genome. Science. 2004;304(5675):1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1098119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ledford H. Circular RNAs throw genetics for a loop. Nature. 2013;494(7438):415. doi: 10.1038/494415a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meldrum C., Doyle M.A., Tothill R.W. Next-generation sequencing for cancer diagnostics: a practical perspective. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2011;32(4):177–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji Z., Song R., Regev A., Struhl K. Many lncRNAs, 5'UTRs, and pseudogenes are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y., Li H., Fang S., Kang Y., Wu W., Hao Y., Li Z., Bu D., Sun N., Zhang M.Q., Chen R. NONCODE 2016: an informative and valuable data source of long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D203–D208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozsolak F. Third-generation sequencing techniques and applications to drug discovery. Expet Opin. Drug Discov. 2012;7(3):231–243. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.660145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shendure J., Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26(10):1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niazi F., Valadkhan S. Computational analysis of functional long noncoding RNAs reveals lack of peptide-coding capacity and parallels with 3′ UTRs. RNA. 2012;18(4):825–843. doi: 10.1261/rna.029520.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halvorsen M., Martin J.S., Broadaway S., Laederach A. Disease-associated mutations that alter the RNA structural ensemble. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volders P.J., Helsens K., Wang X., Menten B., Martens L., Gevaert K., Vandesompele J., Mestdagh P. LNCipedia: a database for annotated human IncRNA transcript sequences and structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D246–D251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aziz N., Zhao Q., Bry L., Driscoll D.K., Funke B., Gibson J.S., Grody W.W., Hegde M.R., Hoeltge G.A., Leonard D.G., Merker J.D., Nagarajan R., Palicki L.A., Robetorye R.S., Schrijver I., Weck K.E., Voelkerding K.V. College of American Pathologists' laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing clinical tests. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2015;139(4):481–493. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0250-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamps R., Brandao R.D., Bosch B.J., Paulussen A.D., Xanthoulea S., Blok M.J., Romano A. Next-generation sequencing in oncology: genetic diagnosis, risk prediction and cancer classification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms18020308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kung J.T., Colognori D., Lee J.T. Long noncoding RNAs: past, present, and future. Genetics. 2013;193(3):651–669. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]