Summary

Chiral syn-1,3-diols are fundamental structural motifs in many natural products and drugs. The traditional Narasaka-Prasad diastereoselective reduction from chiral β-hydroxyketones is an important process for the synthesis of these functionalized syn-1,3-diols, but it is of limited applicability for large-scale synthesis because (1) highly diastereoselective control requires extra explosive and flammable Et2BOMe as a chelating agent under cryogenic conditions and (2) only a few functional syn-1,3-diol scaffolds are available. Those involving halogen-functionalized syn-1,3-diols are much less common. There are no reported diastereoselective reactions involving chemical fixation of CO2/bromocyclization of homoallylic alcohols to halogen-containing chiral syn-1,3-diols. Herein, we report an asymmetric synthesis of syn-1,3-diol derivatives via direct diastereoselective carboxylation/bromocyclization with both relative and absolute stereocontrol utilizing chiral homoallylic alcohols and CO2 in one pot with up to 91% yield, > 99% ee, and >19:1 dr. The power of this methodology has been demonstrated by the asymmetric synthesis of statins at the pilot plant scale.

Subject Areas: Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Stereochemistry

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Diastereoselective carboxylation/bromocyclization

-

•

Mild conditions

-

•

Pilot-plant-scale synthesis of statins

Chemistry; Organic Chemistry; Stereochemistry

Introduction

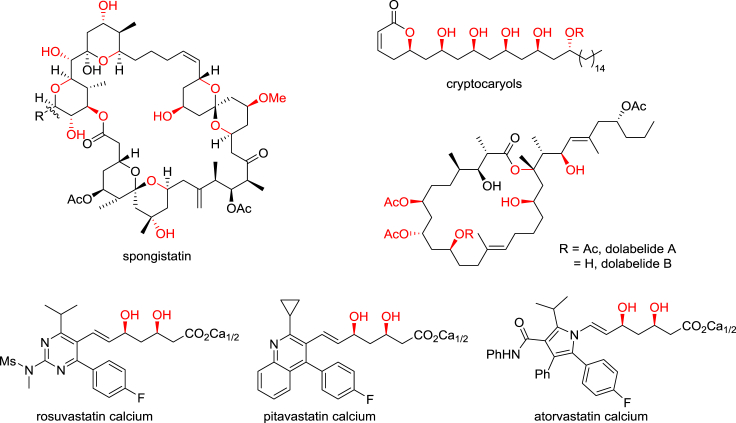

Chiral syn-1,3-diols are ubiquitous and privileged structural motifs in many biologically active polyketide natural products, most prominently represented by the macrolide antibiotics(Norcross and Paterson, 1995, Yeung and Paterson, 2005, Merketegi et al., 2013), and a range of small-molecule drugs, particularly in the statin families (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) (Scheme 1) (Müller, 2005, Časar, 2010, Wu et al., 2015). In addition to direct incorporation into these molecules, chiral syn-1,3-diols are also fundamental building blocks that can easily be elaborated into complex natural products and bioactive molecules. The applications of chiral syn-1,3-diols are also a subject of increasing interest in the pharmaceutical industry (Bode et al., 2006, Gupta et al., 2013, Dechert-Schmitt et al., 2014, Kumar et al., 2017, Quirk et al., 2003, Junoy, 2007, Angelo et al., 2018). For example, a statin analog, rosuvastatin, is used to treat hypercholesterolemia and prevent cardiovascular disease (Shepard et al., 1995, LaRosa et al., 1999), and achieved sales of $4.2 billion in 2017. The unique syn-1,3-diols structure, together with their broad spectrum of physiological activities, fueled intense research activity into their synthesis. Benchmarked by the aldol-directed addition/reduction transformations (Lee and Lin, 2000, Yatagai and Ohnuki, 1990), a considerable number of ingenious methodologies with general utility have been developed. However, the relative and absolute stereocontrol in the construction of these structurally diverse chiral syn-1,3-diols still represents significant challenges. Only a few chiral syn-1,3-diol fragments with proper functional groups, such as aryl, acetate, nitrile and amine, are available. Those involving halogen-functionalized chiral syn-1,3-diols, which are versatile building blocks for the synthesis of syn-1,3-diol-containing natural products and drugs, are much less common. Therefore, there is still a great need for alternative, flexible, and highly stereoselective synthetic methodologies to construct chiral syn-1,3-diol scaffolds.

Scheme 1.

1,3-Diol Polyketide Natural Products and Drugs

Today, the stereocontrolled synthesis of chiral syn-1,3-diols can be achieved by the following two strategies: (1) catalyst-controlled asymmetric reactions (Scheme 2A) (Gupta et al., 2013) and (2) substrate-controlled asymmetric induction, both of which encompass a variety of possible bond disconnections around the hydroxy groups at the C1 and C3 positions. Although various transition metal catalysts and organocatalysts have been developed, no generally applicable approach exists for the flexible synthesis of chiral syn-1,3-diols, and the efficient construction of chiral syn-1,3-diol motifs was realized mainly by a classical Narasaka-Prasad reduction, that is, by securing the chirality of a β-hydroxyketone precursor and then ensuring a syn-diastereoselective reduction using excess Et2BOMe (Scheme 2B) (Narasak and Pai, 1984, Chen et al., 1987). Despite the considerable efficacy, cryogenic reaction conditions are required to achieve high diastereoselectivity. Notably, among several possible approaches to prepare functionalized chiral syn-1,3-diols, the direct diastereoselective electrophilic iodocarboxylation of homoallylic alcohols is clearly underexploited (Scheme 2C) (Ahmad et al., 1977, Bartlett et al., 1982, Duan et al., 1993, Xiong et al., 2016). Although this method requires additional transformation to extend the nucleophilic character of β-hydroxy group by forming esters such as cyclic phosphates and carbonates, the method allows the installation of the functionalized chiral syn-1,3-diol subunits in one step with high efficiency. However, this iodocarboxylation is limited by the inherent instability of the expensive iodo-1,3-dicarbonate products, and there are no reported diastereoselective bromocarboxylations using the chemical fixation of CO2 with chiral homoallylic alcohols to generate chiral syn-1,3-diols.

Scheme 2.

Methods for the Synthesis of syn-1,3-Diols

(A–D) (A) Hydrogenation of 1,3-hydroxyketones to chiral syn-1,3-diols. (B) Cryogenic Narasaka-Prasad reduction to chiral syn-1,3-diols (currently dominates in the industry). (C) nBuLi-mediated iodocarboxylation to racemic syn-1,3-diols. (D) This work: substrate-induced diastereoselective bromocarboxylation to chiral syn-1,3-diols.

In our attempt to synthesize chiral syn-1,3-diol building blocks, we envisioned that CO2 could be an ideal oxygen source to introduce the second hydroxy group when using homoallylic alcohols. However, due to its thermodynamic stability, the chemical fixation of CO2 and its application in the production of valuable fine chemicals still represent major challenges (Klankermayer et al., 2016, Liu et al., 2015, Appel et al., 2013, Sakakura et al., 2007). In previous transformations involving CO2 fixation to unsaturated alcohols, strong bases (such as nBuLi, Scheme 2C), or high CO2 pressures, were generally required (Cardill et al., 1981, Bongini et al., 1982, Tirado and Prieto, 1993, Kielland et al., 2013, Yu and He, 2015). In 2010, Minakata and coworkers described an innovative and extremely mild procedure for the synthesis of trans-1,2-diol (Minakata et al., 2010). Inspired by these fundamental results, we hypothesized that a transient alkylcarbonic acid, in situ prepared from CO2 and a homoallylic alcohol, could react with a cyclic bromonium intermediate in the presence of tBuOCl and NaBr to give syn-1,3-diols (Scheme 2D). Moreover, the chirality of syn-1,3-diols could be obtained via chiral homoallylic alcohol transfer. Herein, we described the first stereocontrolled synthesis of chiral syn-1,3-diol motifs via a one-pot CO2 fixation/bromocyclization using various chiral homoallylic alcohols under extremely mild conditions in up to 91% yield, >99% ee, and >19:1 dr. This 1,3-asymmetric induction methodology was successfully applied in the asymmetric total synthesis of statins on the pilot plant scale.

Results and Discussion

To validate the feasibility of our hypothesis, we first investigated the reaction using chiral homoallylic alcohol (1a) and tBuOCl (2 equiv) with KBr (1.5 equiv) under a balloon of CO2 in acetonitrile at −20°C. As shown in Table 1, the desired chiral six-membered cyclic bromocarbonate 2a was generated in 16% isolated yield with excellent diastereoselectivity (>19:1, entry 1). To improve the efficiency of this bromocyclization, a variety of solvents were evaluated. Switching to a less polar solvent, THF, resulted in only 10% yield but good diastereoselectivity (entry 2). When using dichloromethane or ethyl acetate, the desired product was not formed even after a longer reaction time (entries 3 and 4). In comparison, the use of DMF (N,N-Dimethylformamide) as the solvent tremendously improved the yield of 2a to 65% (entry 5), which can be attributed to the good solubility of NaBr in DMF. However, kindred dimethylacetamide (DMA) led to an inferior yield (entry 6). When protic solvents, such as MeOH or HOAc, were employed, consumption of substrate 1 was detected, but no bromocarbonate product was detected (entries 7 and 8).

Table 1.

Screening Conditions for the Bromocarboxylation of Chiral Homoallylic Alcohols

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | MBr | tBuOCl (eq) | CO2 (atm) | Solvent | Temp (°C) | T (h) | Yield (%)a, b | drc |

| 1 | KBr | 2 | 1 | MeCN | −20 | 3 | 16 | >19:1 |

| 2 | KBr | 2 | 1 | THF | −20 | 3 | 10 | >19:1 |

| 3 | KBr | 2 | 1 | DCM | −20 | 5 | <5 | – |

| 4 | KBr | 2 | 1 | EA | −20 | 5 | <5 | – |

| 5 | KBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −20 | 1.5 | 65 | >19:1 |

| 6 | KBr | 2 | 1 | DMAc | −20 | 1 | 21 | >19:1 |

| 7 | KBr | 2 | 1 | MeOH | −20 | 5 | <5 | – |

| 8 | KBr | 2 | 1 | HOAc | −20 | 5 | <5 | – |

| 9 | NH4Br | 2 | 1 | DMF | −20 | 2 | <5 | – |

| 10 | LiBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −20 | 1.5 | <5 | – |

| 11 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −20 | 1 | 73 | >19:1 |

| 12 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | r.t | 0.5 | 35 | >19:1 |

| 13 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | 0 | 0.5 | 52 | >19:1 |

| 14 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −10 | 1 | 61 | >19:1 |

| 15 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −30 | 2 | 81 | >19:1 |

| 16 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −40 | 3 | 86 | >19:1 |

| 17 | NaBr | 2 | 1 | DMF | −50 | 3 | 84 | >19:1 |

| 18 | NaBr | 1.5 | 1 | DMF | −40 | 3 | 69 | >19:1 |

| 19 | NaBr | 1 | 1 | DMF | −40 | 3 | 41 | >19:1 |

| 20 | NaBr | 2.5 | 1 | DMF | −40 | 3 | 87 | >19:1 |

| 21 | NaBr | 2 | 5 | DMF | −40 | 3 | 88 | >19:1 |

| 22 | NaBr | 2 | 10 | DMF | −40 | 3 | 87 | >19:1 |

THF, tetrahydrofuran; EA, ethyl acetate; DCM, dichloromethane.

General conditions: 1a (1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), CO2 (x atm), tBuOCl (x mmol), MBr (x mmol), solvent (6 mL).

Isolated yields of 2a.

The diastereoselectivity was determined by 1H NMR.

We next investigated other representative alkali metal bromides, including NaBr, NH4Br, and LiBr (entries 9–11). NaBr proved to be a superior bromination reagent with high reactivity and selectivity, giving the desired product in 73% yield in 1 hr (entry 11). In contrast, more soluble bromides, NH4Br and LiBr, failed to produce expected bromocarbonate 2a (entries 9 and 10). The reaction temperatures were also examined, and the reaction yields were dependent on the temperatures. Increasing the temperature led to decreased reaction yields and diastereoselectivities (entries 12–15). In contrast, the formation of 2a could be improved by conducting the reaction at lower temperatures. At −40°C, the reaction afforded the optimal results with 86% yield and >19:1 diastereoselectivity within 3 hr (entry 16). When the temperature was decreased further, the yield of the reaction remained essentially the same (entry 17).

Changing the equivalence of tBuOCl and CO2 was also discussed. Decreasing the amount of tBuOCl significantly decreased the yield of this reaction (entries 18 and 19), whereas increasing the amount did not improve the yield (entry 20). Simultaneously, improving the pressure of CO2 slightly improved the yield but special equipment was needed, which made the procedure impractical (entries 21, 22). Thus, we selected tBuOCl (2 equiv) with NaBr(1.5 equiv) under a balloon of CO2 in DMF and at −40°C as the reaction conditions. Notably, when using iodide as the nucleophile, no desired syn-1,3-diol was produced, suggesting that iodide was not suitable for this reaction.

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we investigated the substrate scope of this reaction with various chiral homoallylic alcohols. As illustrated in Table 2, this new system indicated excellent substrate compatibility, giving the desired carbonate products in good to excellent isolated yields and diastereoselectivities. First, the ester-containing substrates performed well and afforded the desired syn-isomer products in excellent yields (79%–86%) and high diastereoselectivities (>19:1) (2a-e). Replacing the ester groups with various oxy groups, including electron-rich benzyloxy (2f, 2g), electron-deficient p-toluenesulfonic ester (OT)s (2h), or sterically bulky alkoxy (2i, 2j) or silyloxy groups (2k, 2l), all led to bromocarbonate products in identical performances. With general alkyl (2m), benzyl (2n, 2o), or aryl substituents (2p, 2q), this reaction also worked well and produced the desired products. In addition, heterocycles, such as thienyl (2r), reacted smoothly to give the desired product in good yield and diastereoselectivity. Moreover, some highly reactive functional groups, such as Cl (2s) and CN (2t), were also tolerated under these reaction conditions. Substrates bearing geminal substituents were also converted into the corresponding products (2u). Notably, when homoallylic alcohols with mono- (2v, 2w) or disubstituted (2x, 2y) double bonds were used, the carbonate products were generated in moderate yields (25%–45%), but the good diastereoselectivities remained. To further evaluate the synthetic utility of this method, we attempted to use the opposite configuration of the (S)-homoallylic alcohols. Fortunately, satisfactory yields and diastereoselectivities were obtained with all these substrates, which not only highlighted the excellent substrate compatibility but also implied the great potential of this new method for synthesizing chiral syn-1,3-diols (3a-e). More importantly, the enantiopurity of the starting material was retained, and 99% ee was detected in all cases after purification.

Table 2.

Survey of the Substrate Scope in the Diastereoselective Bromocarboxylation of Chiral Homoallylicalcohols

|

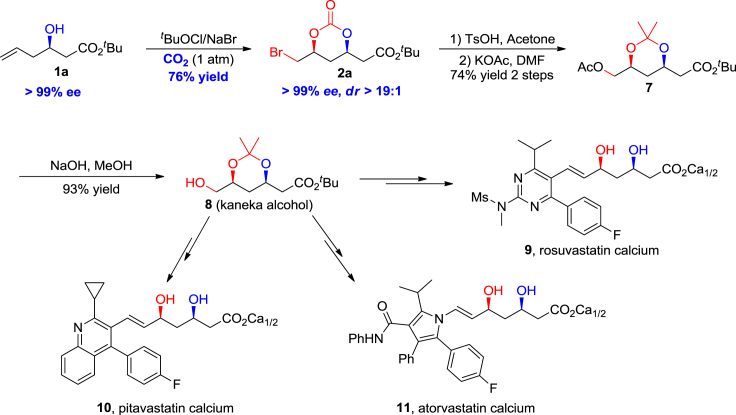

Industrial Application

The aforementioned chiral syn-1,3-diol-bromocarbonates are valuable building blocks for the asymmetric synthesis of syn-1,3-diol-containing natural products and drugs, and the power of this methodology was demonstrated in the pilot-plant-scale synthesis of chiral syn-1,3-diol-derived statins, including rosuvastatin, pitavastatin, and atorvastatin. As depicted in Scheme 3, chiral homoallylic alcohol 1a was subjected to tBuOCl and NaBr in DMF at −40°C under a continuously bubbling CO2 system to give, after crystallization, pure bromocarbonate product 2a in 76% yield, >99% ee, and >19:1 dr without column chromatography isolation. Compound 2a was then converted to acetate 7 in two steps via acetonidation (Clive et al., 1990, Radl et al., 2002, Beck et al., 1995) followed by an SN2 reaction with a total yield of 74%. Subsequent hydrolysis of the acetate proceeded smoothly to give Kaneka alcohol 8 in 93% yield (Fan et al., 2011, Sun et al., 2007), which could be transformed to the final rosuvastatin 9 via known procedures (Wess et al., 1990). Moreover, from the general intermediate Kaneka alcohol 8, other statins in this family, such as pitavastatin 10 (Choi and Shin, 2008) and atorvastatin 11 (Rádl, 2003), could be easily prepared on scales up to kilograms. Notably, asymmetric total syntheses of statins have been well documented in the literature (Chen et al., 2014, Xiong et al., 2015). However, this methodology is the first example using CO2 as oxygen source to construct the important chiral syn-1,3-diol structure. Right now, this procedure was patented and processed in a pharmaceutical company (Chen et al., 2017).

Scheme 3.

Pilot-Plant-Scale Synthesis of Statins

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a one-pot diastereocontrolled synthesis of chiral syn-1,3-diol derivatives via CO2 fixation/bromocyclization using in situ-generated tBuOBr in excellent yield and with both relative and absolute stereocontrol. This transformation is tolerant of a wide range of functional groups and can easily be scaled up to the hectogram scale without racemization, providing ready access to a broad range of chiral syn-1,3-diol products. Further application of this method to the synthesis of statins highlighted the great synthetic capability of this methodology. Ongoing new synthetic approach toward chiral syn-1,3-diol-containing natural products and medicines using this method is now underway in our laboratory.

Limitations of Study

Excess amounts of oxidant and source of bromides are generally needed. Substitutions on the alkenes also inhibited this reaction with decreased reactivity.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

Huang G. X. acknowledgements Dr. Huang and Dr. Cheng for insightful discussion.

Author Contributions

Methodology, G.H. and F.C.; Investigation, G.H. and M.L.; Writing – Original Draft, G.H.; Writing – Review & Editing, H.P., and F.C.; Supervision, H.P.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Published: November 30, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Transparent Methods and 95 figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.11.010.

Contributor Information

Haihui Peng, Email: haihui_peng@fudan.edu.cn.

Fener Chen, Email: rfchen@fudan.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- Ahmad M., Bergstrom R.C., Cashen M.J., McClelland R.A., Powell M.F. “Phosphate extension”. A strategem for the stereoselective functionalization of acyclic homoallylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:4829–4830. [Google Scholar]

- Angelo M.L., Moreira L.M., Ruela A.L.M., Morais A.L., Santos A.L.A., Salgado H.R.N., Magali B.A. Analytical methods for the determination of rosuvastatin in pharmaceutical formulations and biological fluids: a critical review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018;48:317–329. doi: 10.1080/10408347.2018.1439364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel A.M., Bercaw J.E., Bocarsly A.B., Dobbek H., DuBois D.L., Dupuis M., Ferry J.G., Fujita E., Hille R., Kenis P.J.A. Frontiers, opportunities, and challenges in biochemical and chemical catalysis of CO2 fixation. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:6621–6658. doi: 10.1021/cr300463y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett P.A., Meadows J.D., Brown E.G., Morimoto A., Jernstedt K.K. Carbonate extension. A versatile procedure for functionalization of acyclic homoallylic alcohols with moderate stereocontrol. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:4013–4018. [Google Scholar]

- Beck G., Jendralla H., Kesseler K. Practical large scale synthesis of tert-butyl (3R,5S)-6-hydroxy-3,5-O-isopropylidene-3,5-dihydroxyhexanoate: essential building block for HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Synthesis. 1995;8:1014–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Bode S.E., Wolberg M., Müller M. Stereoselective synthesis of 1,3-diols. Synthesis. 2006;4:557–588. [Google Scholar]

- Bongini A., Bongini G., Orena M., Porzi G., Sandri S. Regio- and Stereocontrolled synthesis of epoxy alcohols and triols from allylic and homoallylic alcohols via iodo carbonates. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:4626–4633. [Google Scholar]

- Cardill G., Orena M., Porzi G., Sandri S. A new regio- and stereo-selective functionalization of allylic and homoallylic alcohols. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1981;10:465–466. [Google Scholar]

- Časar Z. Historic Overview and recent advances in the synthesis of super-statins. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010;14:816–845. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.R.; Huang, G.X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.D.; Liu, M.J. (2017). CN 106588865 A.

- Chen K.M., Hardtmann G.E., Prasad K., Repic O., Shapiro M. 1,3-syn diastereoselective reduction of β-hydroxyketones utilizing alkoxydialkylboranes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.F., Xiong F.J., Chen W.X., He Q.Q., Chen F.R. Asymmetric synthesis of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor atorvastatin calcium: an organocatalytic anhydride desymmetrization and cyanide-free side chain elongation approach. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:2723–2728. doi: 10.1021/jo402829b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.W., Shin H. Efficient synthesis of (3R, 5S)-3,5,6-trihydroxyhexanoic acid derivative as a chiral side chain of statins. Synlett. 2008;10:1523–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Clive D.L.J., Murthy K.S.K., Wee A.G.H., Prasad J.S., da Silva G.V.J., Majewski M., Anderson P.C., Evans C.F., Haugen R.D., Heerze L.D., Barrie J.R. Total synthesis of both (+)-compactin and (+)-mevinolin. A general strategy based on the use of a special titanium reagent for dicarbonyl coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:3018–3028. [Google Scholar]

- Dechert-Schmitt A.-M., Schmitt D.C., Gao X., Itoh T., Krische M.J. Polyketide construction via hydrohydroxyalkylation and related alcohol C-H functionalizations: reinventing the chemistry of carbonyl addition. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31:504–513. doi: 10.1039/c3np70076c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J.J.W., Sprengeler P.A., Smith A.B., III Iodine monobromide (IBr) at low temperature: enhanced diastereoselectivity in electrophilic cyclizations of homoallylic carbonates. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:3703–3711. [Google Scholar]

- Fan W.Z., Li W.F., Ma X., Tao X.M., Li X.M., Yao Y., Xie X.M., Zhang Z.G. Ru-Catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of γ-heteroatom substituted β-keto esters. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:9444–9451. doi: 10.1021/jo201822k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P., Mahajan N., Taneja S.C. Recent advances in the stereoselective synthesis of 1,3-diols using biocatalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013;3:2462–2480. [Google Scholar]

- Junoy J.P. The impact of generic reference pricing interventions in the statin market. Health Policy. 2007;84:14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielland N., Whiteoak C.J., Kleij A.W. Stereoselective synthesis with carbon dioxide. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013;355:2115–2138. [Google Scholar]

- Klankermayer J., Wesselbaum S., Beydoun K., Leitner W. Selective catalytic synthesis using the combination of carbon dioxide and hydrogen: catalytic chess at the interface of energy and chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:7296–7343. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Tripathi D., Sharma B.M., Dwivedi N. Transition metal catalysis-a unique road map in the stereoselective synthesis of 1,3-polyols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:733–761. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01925k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRosa J.C., He J., Vupputuri S.J. Effect of statins on risk of coronary diseasea meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282:2340–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.S., Lin L.S. Synthesis of allyl ketone via Lewis acid promoted Barbier-type reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8803–8806. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Wu L., Jackstell R., Beller M. Using carbon dioxide as a building block in organic synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5933–5947. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merketegi J.L., Albericio F., Álvarez M. Tetrahydrofuran-containing macrolides: a fascinating gift from the deep sea. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:4567–4610. doi: 10.1021/cr3004778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakata S., Sasaki I., Ide T. Atmospheric CO2 fixation by unsaturated alcohols using tBuOI under neutral conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:1309–1311. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of building blocks for statin side chains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:362–365. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasak K., Pai F.C. Stereoselective reduction of β hydroxyketones to 1,3-diols highly selective 1,3-asymmetric induction via boron chelates. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:2233–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross R.D., Paterson I. Total synthesis of bioactive marine macrolides. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2041–2114. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk J., Thornton M., Kirkpatrick P. Rosuvastatin calcium. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:769–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rádl S. A New Way to tert-Butyl [(4R,6R)-6-Aminoethyl-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-4-yl]acetate, a key intermediate of atorvastatin synthesis. Synth. Commun. 2003;33:2275–2283. [Google Scholar]

- Radl S., Stach J., Hajicek J. An improved synthesis of 1,1-dimethylethyl 6-cyanomethyl-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxane-4-acetate, a key intermediate for atorvastatin synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:2087–2090. [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura T., Choi J.-C., Yasuda H. Transformation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:2365–2387. doi: 10.1021/cr068357u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard J., Cobbe S.M., Ford I., Isles C.G., Lorimer A.R., MacFarlane P.W., McKillop J.H., Pachard C.J.N. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F.L., Xu G., Wu J.P., Yang L.R. A new and facile preparation of tert-butyl (3R,5S)-6-hydroxy-3,5-O-isopropylidene-3,5-dihydroxyhexanoate. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2007;18:2454–2461. [Google Scholar]

- Tirado R., Prieto J.A. Stereochemistry of the iodocarbonatation of cis- and trans-3-methyl-4-pentene-1,2-diols: the unusual formation of several anti iodo carbonates. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5666–5673. [Google Scholar]

- Wess G., Kesseler K., Baader E., Bartmann W., Beck G., Bergmann A., Jendralla H., Bock K., Holzstein G., Kleine H., Schnierer M. Stereoselective synthesis of HR 780 a new highly potent HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:2545–2548. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Xiong F.J., Chen F.R. Stereoselective synthesis of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl-ecoenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:8487–8510. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong F.J., Wang H.F., Yan L.J., Xu L.J., Tao Y., Wu Y., Chen F.R. Diastereoselective synthesis of pitavastatin calcium via bismuth-catalyzed two-component hemiacetal/oxa-Michael addition reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:9813–9819. doi: 10.1039/c5ob01148e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong F.J., Wang H.F., Yan L.J., Han S., Tao Y., Wu Y., Chen F.E. Stereocontrolled synthesis of rosuvastatin calcium via iodine chloride-induced intramolecular cyclization. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:1363–1369. doi: 10.1039/c5ob02245b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatagai M., Ohnuki T. Asymmetric reduction of functionalized ketones with a sodium borohydride-(L)-tartaric acid system. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 1990;1:1826–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K.S., Paterson I. Advances in the total synthesis of biologically important marine macrolides. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4237–4313. doi: 10.1021/cr040614c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B., He L.N. Upgrading carbon dioxide by incorporation into heterocycles. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:52–62. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201402837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.