Clinical vignette

A 33-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to hospital with recent onset of jaundice of 2–3 weeks duration. He reported heavy use of alcohol for the last 10 years with the last drink a day prior to the onset of symptoms. At admission, he was alert and oriented to time, place, and person, and was deeply jaundiced. His laboratory profile can be summarised as follows: haemoglobin 12.1 g/dl, white blood cell count 18,700 with 81% neutrophils, serum bilirubin 33 (direct 22) mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase 147 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 62 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 117 IU/L, serum albumin 2.8 gm/dl, serum creatinine 0.6 mg/dl, prothrombin time 18.3 (control 14.5) seconds, and international normalized ratio 1.48. He was diagnosed with severe alcoholic hepatitis (Maddrey discriminant function score of 50) and treated with prednisolone for 28 days with symptomatic and biochemical improvement. His Lille score at seven days was 0.4, and his serum bilirubin had decreased to 3.5 mg/dl at the end of treatment. He was also seen by the addiction team during hospitalisation; he agreed to follow through on recommendations. He was dismissed after completing a three-week inpatient rehabilitation programme but relapsed to alcohol use three months later, and was readmitted with alcohol withdrawal. He was readmitted two months later (about six months from the first episode) for a second episode of severe alcoholic hepatitis. At admission, his model for end-stage liver disease score was 32 and he was treated again with corticosteroids. His Lille score at seven days was 0.6 and steroids were discontinued. The hospital course was complicated by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and pneumonia with development of acute kidney injury. He continued to worsen, developing multiorgan failure. After a course of one month, the family’s preference was for him to receive comfort measures.

This scenario raises several questions:

I. Should liver biopsy have been carried out in this patient before starting treatment for alcoholic hepatitis?

II. What should the protocol be for early diagnosis of infection?

III. Are there options other than steroid therapy for severe alcoholic hepatitis? Should pharmacological therapy have been initiated to prevent alcohol relapse?

IV. What are the determinants of short-term and long-term prognosis in alcoholic hepatitis?

V. What is the role of liver transplantation in alcoholic hepatitis?

Keywords: Alcoholic liver disease, Liver biopsy, Corticosteroids, Liver transplantation

Introduction

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a clinical syndrome occurring in patients with chronic and active heavy alcohol use. Patients present with jaundice and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and may progress to acute-on-chronic liver failure. Patients with severe AH have mortality of up to 30–40% at 28 days from the initial presentation. Optimal management requires a team including a hepatologist, addiction specialist, nutrition expert and a social worker. Corticosteroids are the only available medical therapy for specific treatment of patients with severe AH. However, use of corticosteroids is limited by non-response in approximately 40% of patients, potential for side effects, and lack of mortality benefit beyond one month. Over the last few years, there has been an increasing interest in early liver transplantation as salvage therapy for non-responders to corticosteroids. However, despite consistent reports of benefit, barriers remain to universal acceptance of early liver transplantation.

I. Should liver biopsy have been carried out in this patient before starting treatment for alcoholic hepatitis?

To answer this question, we will discuss clinical criteria for diagnosis of AH before discussing the role of liver biopsy.

Clinical criteria for diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis should be suspected in patients with known alcoholic liver disease or heavy alcohol use for >6 months who present with recent onset or worsening of jaundice with <60 days of abstinence before the onset of jaundice. Clinical diagnosis of AH requires demonstration of heavy alcohol use as the aetiological factor in the absence of other known causes of liver disease, and the presence of hepatitis. The threshold for the absolute amount of alcohol consumed, that is, the amount and duration of alcohol use, is unknown. Average consumption of three or more drinks (40 grams) per day for women and four or more drinks (50–60 grams) per day for men is accepted as a minimal threshold for diagnosis of AH. Alcohol use is typically for years, and for diagnosis of AH should include the period within two months of presentation. Hepatitis requires a clinical diagnosis, with manifestations including rapid onset of jaundice with serum bilirubin ≥3 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >50 IU/ml and <500 IU/ml, and an AST: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio of >1.5.1 Additionally, immune, metabolic, viral and other causes of liver disease should be excluded (Fig. 1).

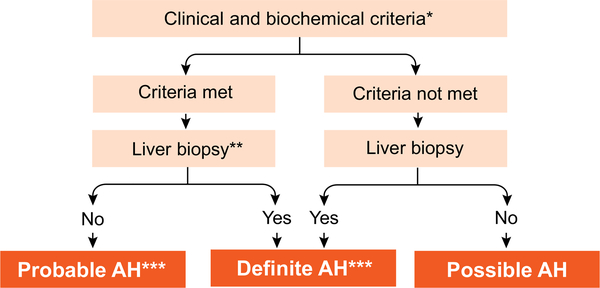

Fig. 1. Algorithm for diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis.

*Clinical criteria: Heavy alcohol use (>2 drinks in females and >3 drinks in males) for >5 years; Active alcohol use until at least 8 weeks prior to presentation; Recent (<1 month) onset or worsening of jaundice; Exclude other liver diseases, biliary obstruction, HCC. *Biochemical criteria: Serum bilirubin >3 mg/dl, AST >50 and <500, AST >ALT by 1.5:1; **Transjugular route preferred for obtaining the liver tissue. **Characteristic histological findings: Cell balooning, neutrophil infiltration, cholestasis, varying degree of steatosis and fibrosis. ***Needed for inclusion in clinical trials and before starting specific pharmacologic therapy. AH, alcoholic hepatitis; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Because of the reluctance of many physicians and patients to obtain a liver biopsy, based on expert recommendation, diagnosis of AH has been stratified as A) Definite AH: meeting clinical criteria (alcohol use in excess and laboratory evidence of hepatitis as defined earlier), and confirmation of diagnosis on liver biopsy; B) Probable AH: defined when a patient has both alcohol use disorder and hepatitis, and investigations have ruled out other causes of liver disease, including shock or sepsis, or recent cocaine or drug use; and C) Possible AH: defined in patients in whom the clinical diagnosis is confounded by i) recent upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, ischemic hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury, ii) atypical AST and ALT pattern, or iii) uncertainty in the history of alcohol use (Fig. 1). In such patients, a liver biopsy is essential for diagnosis of AH and for inclusion into AH treatment studies.1

Role of liver biopsy

The European Association for Study of Liver recommends a liver biopsy to establish a diagnosis of AH,2 because in up to 30% of patients clinically diagnosed as having AH liver biopsy may lead to an alternative diagnosis.3,4 In practice, however, liver biopsy is used for definitive diagnosis of AH when the clinical diagnosis is uncertain. Histological diagnosis is based on characteristic histological findings of hepatocyte ballooning, neutrophil infiltrate, Mallory-Denk bodies, together with varying degrees of steatosis and fibrosis, depending on the stage of the disease and the time elapsed from the last alcohol consumption.5,6 Fibrosis is typically perivenular and pericellular, that is, a “chicken-wire fence” pattern. Centralcentral and central-portal septa, which are typical of micro-nodular cirrhosis, may be seen.

As the majority of patients with severe AH have ascites and coagulation disorders, the transjugular route is preferred for liver biopsy (Fig. 1). A systematic review confirms the safety of transjugular liver biopsy with a mortality rate of 0.09% and a complication rate of 6.7%.7 However, the transjugular liver biopsy procedure is not available at many centres, and fear of complications from a percutaneous biopsy limit widespread use of liver biopsy.8 Liver biopsy may also have a prognostic value. For example, a scoring system based on mega mitochondria, neutrophil infiltrate, cirrhosis and bilirubin stasis helps identify patients at high risk of short-term mortality.9 The severity of AH based on histology has also been correlated with outcome in an independent study.4 Further studies are needed to assess whether the findings on histology can be used to determine the choice of therapy or response to treatment.

Unfortunately, we lack accurate non-invasive markers to diagnose AH. Recently, two studies have shown that plasma levels of fragments of cytokeratin 18 may be used for non-invasive diagnosis of AH, but measurement of these fragments has not yet been introduced into clinical practice.10,11 Similarly, in another translational study, analysing the bioenergetics and mitochondrial function of monocytes in patients with decompensated alcoholic liver disease showed that a reduction in bioenergetics is a potential biomarker for diagnosis of AH.12,13 Currently, despite some limitations, a liver biopsy is recommended to diagnose AH when the clinical diagnosis is uncertain.1

II. What should the protocol be for early diagnosis of infection?

Understanding the pathophysiology of AH and its complications are important to inform diagnostic work-up for infections in patients hospitalised with severe AH.

Pathophysiology of alcoholic hepatitis

Liver injury from alcohol occurs via direct toxicity of the parent compound as well as toxicity of its metabolites. In addition, liver damage occurs indirectly through intestinal dysbiosis from effects of alcohol on the intestines (Fig. 2).14 The profile of dysbiosis in AH is not fully codified. It is broadly postulated that alcohol changes the normal flora to one that increases lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other toxic bacterial metabolites, and their delivery to the liver through the portal vein.15 Recent evidence suggests that there may also be dysbiosis of fungi and perhaps viral residents in the intestines as well.16 Presently, it is unclear whether the microbiome relevant to causing disease pathogenesis resides in the small bowel or colon. Further, the biliary microbiome has not been studied but may be important. Alcohol also increases gut permeability by mediating the increase in paracellular permeability.17 This effect may be mediated through the direct action of alcohol on the intestinal epithelium and/or through indirect effects of circulating blood alcohol. The combination of increased gut permeability and intestinal dysbiosis leads to delivery of bacterial products through the portal vein into the liver causing the classic sterile necrosis response mediated by pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The PAMPs in turn activate macrophages leading to an inflammatory macrophage phenotype and a downstream canonical inflammatory response that includes neutrophil recruitment to sites of sterile necrosis, mediated via the release of chemokines by macrophages.18

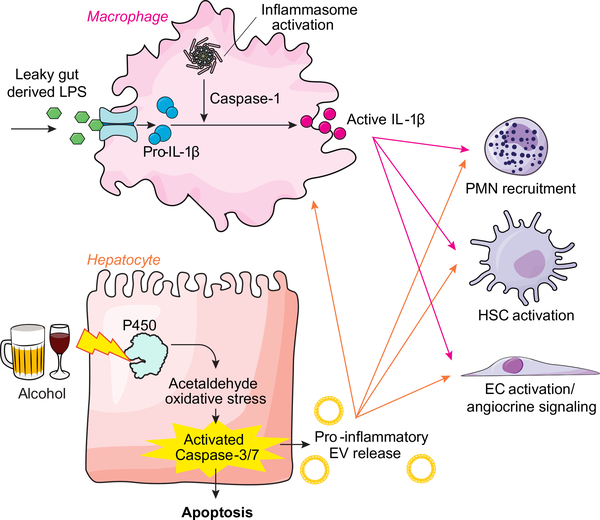

Fig. 2. Pathophysiology of alcoholic hepatitis.

Alcohol-induced liver injury occurs through a convergence of toxic effects of alcohol on the intestine which affect the liver indirectly as well as direct toxic effects of alcohol on hepatocytes. Indirect gut effects occur from alcohol-induced increases in bacterial translocation including LPS that lead to IL-1B production from liver macrophages. Direct effects of alcohol on hepatocytes generate acetaldehyde and oxidative stress, which leads to hepatocyte apoptosis and release of EVs. These EVs together with IL-1B act on other liver cell types including PMN cells, HSCs, and ECs to propagate inflammation and fibrosis that is observed in alcoholic liver disease (slide courtesy of Dr. Vikas Verma). EC, endothelial cell; EV, extracellular vesicle; HSC, hepatic stellate cell; IL-1B, interleukin-1 beta; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PMN, polymorphonuclear.

The direct effects of alcohol on the liver are also salient. Alcohol and its metabolite, acetaldehyde, leads to apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes.19 This hepatocyte injury in turn leads to the release of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which can also stimulate liver macrophages in a similar way to that described for PAMPs.18 Thus, the combination of alcohol-induced injury directly on hepatocytes with DAMP release, as well as the alcohol-induced effects on the gut with subsequent PAMP release, culminates in liver inflammation which is the classical feature of AH.

Infection in alcoholic hepatitis

Infection is a frequent event in severe AH, and is one of the major factors influencing mortality.20–22 Pathophysiological changes resulting from direct and indirect effects of alcohol on the liver (Fig. 2) impair the immune response, predisposing patients with severe AH to infections. While it is paradoxical that neutrophil infiltration of the liver is associated with an increased risk of infection,23 various abnormalities in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe AH, such as decreased oxidative burst in monocytes,24 and in neutrophils,25 lower exocytosis of myeloperoxidase,26 and changes in checkpoint inhibitors predispose these patients to development of infections.27 These data suggest that there are several theoretical targets for therapeutic intervention in order to reverse immune dysfunction in severe AH.28 Furthermore, an exaggerated compensatory response to SIRS and cytokine signalling in AH, instead of halting the inflammatory signalling is associated with immune paralysis, which in concert with the aforementioned immune dysfunction creates a perfect setting for worsening of liver failure and development of infections.27,29,30

Diagnosing infection early in patients with severe AH is challenging because SIRS is frequent in patients with AH even in the absence of infection and bacterial cultures are frequently negative.4,21 There are no prospective studies to derive an evidence-based algorithm to identify infections in patients with AH. Infection is suspected when patients have SIRS, which is diagnosed if two or more of the following criteria are met: temperature >38 °C or <36 °C; heart rate >90 beats/minute; respiration >20/minute; WBC >12,000/μl or <4,000/μl or >10% immature forms. However, SIRS may occur even in the absence of infection. If systematic screening is applied at admission (Fig. 3), around 25% of patients have infection, mainly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bacteraemia and urinary tract infection.20,30 It seems reasonable to recommend blood cultures, urine culture and chest X-ray and ascitic fluid examination in all patients.20,28 C-reactive protein or procalcitonin levels have limited utility in the diagnosis of infection in cirrhosis and AH.20,21,31 Conversely, bacterial DNA and LPS may be attractive tools to diagnose early infection but such a strategy is expensive and needs validation before routine clinical use.21,32

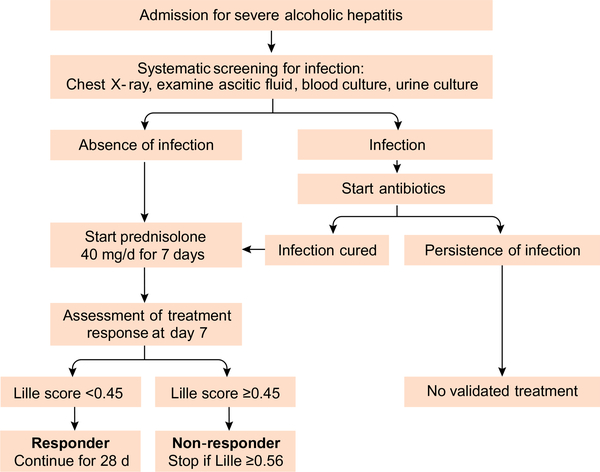

Fig. 3.

Algorithm for surveillance of infections in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

The question of whether corticosteroids predispose patients with AH to infections is debatable. In the largest randomised controlled trial, Steroids Or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH), patients who received prednisolone had a higher risk of infection (13% vs. 7% in patients without prednisolone) but prednisolone improved 28-day survival.33 A meta-analysis of all randomised controlled trials on corticosteroids in AH, including the STOPAH study showed that patients treated with prednisolone had no increased risk of infection compared to patients treated with placebo.22 However, corticosteroid use was associated with fungal infections. It should be noted that infections in all these trials were detected based on standard of care and no infection screening protocol was in place.

In a post hoc analysis of the STOPAH trial,32 patients with high bacterial DNA levels were more likely to develop infections and had a worse outcome if they were treated with prednisolone rather than receiving placebo. This suggests that some patients have undiagnosed subclinical infection before the initiation of prednisolone and reinforces the need for a systematic screening for infection. Randomised controlled trials are ongoing to determine if antibiotic prophylaxis used as adjuvant to corticosteroids will reduce infection risk and improve outcomes.34

III. Are there options other than steroid therapy for severe AH? Should pharmacological therapy have been initiated to prevent alcohol relapse?

The optimal therapy for AH requires integrated management of the liver disease and alcoholism. Abstinence is an important determinant of long-term outcome and survival.

Optimal pharmacologic therapy for severe AH

Corticosteroids are the most extensively studied treatment for AH based on their ability to inhibit T cell activity, and consequently reduce cytokine signalling (Fig. 2).35 Only 25–45% of patients are eligible for corticosteroid therapy.36,37 Some of the reasons for exclusion include infections in 40–50%, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and active gastrointestinal bleeding.21,29,32,38,39 Survival benefit has been observed in only about 50–60% of treated patients;40 and limited to 1–2 months. Longer term survival depends on underlying liver function and abstinence from alcohol.41 Patients with infection at admission may be treated with corticosteroids after the infection is appropriately controlled, as their response and outcome with corticosteroid treatment is similar to uninfected patients.20 Another pharmacological option has been pentoxifylline, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) activity, one of the major cytokines in the pathogenesis of AH (Fig. 2).42 Although, there is a consensus on its excellent safety profile and renal protective benefit, pentoxifylline use is not associated with improved survival.43 Pentoxifylline was also ineffective as a salvage option for corticosteroid nonresponders,44 or as an adjuvant to corticosteroids.45 The largest randomised controlled study in over 1,100 patients enrolled from 65 centres in the UK, the STOPAH study demonstrated the absence of survival benefit of both corticosteroids and pentoxifylline over placebo in patients with severe AH.43 Corticosteroids provided only a trend for mortality benefit (13.8 vs. 18%, p = 0.06), with 40% reduced risk of death by 28 days after controlling for patient demographics and disease severity. In a recently reported study, intravenous N-acetylcysteine for five days as an adjuvant to corticosteroids improved survival at one month compared to prednisolone alone, because of the reduced risk of hepatorenal syndrome and infections.46 However, the study failed to meet its primary endpoint of improvement in six-month survival.

Other pharmacological options including anti-TNF agents like infliximab and etanercept,47,48 antioxidant cocktails including vitamin E,49 insulin and glucagon,50 testosterone or oxandrolone,51 propylthiouracil,52 and extra-corporeal albumin dialysis53 have been used without any survival benefit.

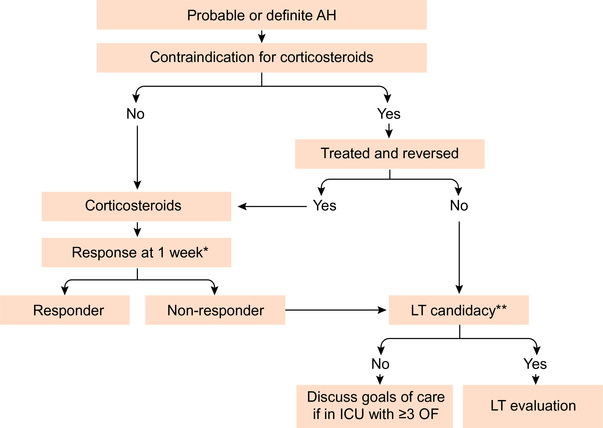

In a network meta-analysis of 22 randomised controlled studies including the STOPAH study, there was moderate quality evidence for a 46% survival benefit at one month with the use of corticosteroids, with no evidence of benefit with pentoxifylline.54 Prednisolone 40 mg per day orally or methylprednisolone 32 mg intravenously for a maximum duration of 28 days is therefore recommended as first-line therapy in patients with severe AH.55 Since approximately 40% of patients in most AH trials do not respond to steroids, and continued steroid use is associated with a higher risk of infection, it is important to identify early patients who are steroid non-responders. Steroid response is unlikely and therapy should be discontinued if the serum bilirubin has not decreased at one week (early biological response). A 25% decrease in bilirubin at one week has been used by some authors as a marker of steroid response.56 The Lille score uses age, renal function, prothrombin time, and albumin at initiation of treatment and the decrease in serum bilirubin at seven days to identify steroid non-responders.40 A Lille score ≥0.45 after one week of steroid therapy indicates non-response with a high risk of death; a score >0.56 warrants discontinuation of corticosteroids (Fig. 4). Steroid therapy should be continued for 28 days if the Lille score is <0.45. Although, there are no guidelines for patients with Lille score between 0.45 and 0.56, it may be reasonable to cautiously continue corticosteroids in these patients for one more week and discontinue if there is no further improvement in clinical and biochemical profile. Progressive liver disease with multiple organ failure is the major cause of death among patients who do not respond to corticosteroids and are not eligible for early liver transplant (LT).22 If these patients have >3 organ failures at the time of determining non-response to corticosteroids, it may be reasonable to consider instituting comfort measures (Fig. 4).57

Fig. 4. Algorithm for optimal management of patients with alcoholic hepatitis.

*Using Lille score. **Excellent psychosocial support in a patient with first episode of AH. AH, alcoholic hepatitis; ICU, intensive care unit; LT, liver transplantation; OF, organ failure.

Until newer more effective and safer pharmacological options are available, strategies to optimise use of corticosteroids may be used, like: a) biomarkers such as mitochondrial bioenergetics and cytokine levels to target patients who are likely to respond to corticosteroids, b) bacterial DNA, bacterial LPS, and procalcitonin to tailor corticosteroid use to patients who are less likely to develop infections, or c) shortening of corticosteroid trial, assessing response at four days of therapy.12,13,21,32,60 Safer and more effective emerging therapies targeting various pathways in the pathogenesis of AH are discussed later.

Complications of liver disease (infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome) require specific therapy as per prevailing guidelines. Patients with malnutrition or severely reduced caloric intake should receive nutritional supplementation, preferably by enteral route, though a recent study of enteral nutrition associated with steroids was not associated with improved survival.55

Novel agents in the management of severe alcoholic hepatitis

For decades, corticosteroids have remained the only effective treatment for patients with severe AH. Several medical therapies are emerging, which target different pathways in the disease pathogenesis as described (Fig. 2). Many of these approaches are existing compounds that are being repurposed for AH and/or drugs in development for which AH has now become a potentially appealing indication. A number of these drugs target the gut-liver axis. For example, altering gut flora through antibiotics, probiotics, or efforts to neutralise bacterial endotoxin and to neutralise the LPS by using an immunoglobulin against this molecule may be beneficial (Fig. 2). Most notably, there is a large clinical trial ongoing in France to ascertain potential benefits of amoxicillin + clavulanate in combination with corticosteroids in patients with AH.81 Other agents under evaluation attempt to target the liver injury response, such as inhibitors of caspase activation, although recent studies were unable to clarify a safe dosing regimen in patients with AH because of excessively high blood levels of the caspase inhibitory compound.82 Additional approaches have focused on the sterile necrosis response with attempts to block various steps in this pathway (Fig. 2). One notable example is anakinra, which blocks the interleukin-1 receptor and may thereby reduce liver inflammation.83 A number of other compounds are also under evaluation that may inhibit hepatic inflammation, including inhibition of various chemokine pathways. Stimulation of liver regeneration is also emerging as an important target for therapy. An interleukin-22 (IL-22) agonist which targets hepatic regeneration is currently being studied in patients with moderate and severe AH. Data on a number of other compounds such as growth factors (G-CSF and erythropoietin) and faecal microbiota transplantation84,85 are encouraging, but require validation before introduction into routine clinical use.

Pharmacological therapy to prevent alcohol relapse

Irrespective of the severity of AH, patients should receive benzodiazepine therapy for alcohol withdrawal. Propofol has been used for severe withdrawal, but the practice is not widespread.58 Relapse to alcohol use occurs in up to 65% of patients at one year, among survivors of the AH episode.43 Of all the available drugs to maintain abstinence, baclofen (started as 5 mg three times daily and slowly increased over 7–10 days to maximum dose of 15 mg three times daily) is safe and effective in maintaining abstinence in these patients with AH.59

IV. Determinants of short-term and long-term prognosis in alcoholic hepatitis

Risk factors for mortality in AH include severity of liver disease, degree of inflammatory response, type and magnitude of infection, histology, response to steroid therapy, and risk of recidivism. Genetic differences are also likely to be prognostic but have not been well-studied. Regarding histology, the presence of isolated steatosis in the first liver biopsy is associated with a low risk of progression to cirrhosis at four years in heavy drinkers.61 However, the presence of AH at baseline is associated with a 40% risk of cirrhosis at four years. A score based on hepatic fibrosis, neutrophil infiltration, cholestasis in hepatocytes and/or bile canaliculi, and mega mitochondria can independently predict 90-day mortality.9 In patients with severe disease, as determined by a histological score of 6–9, the 90-day mortality is approximately 50%.

Prognosis in AH may be determined clinically at initial evaluation, during treatment, and long term among survivors of the index hospitalisation. At admission, the two most widely used scores are the Maddrey discriminant function (MDF) and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score.62,63 Severe AH is diagnosed if the MDF score is ≥32 or the MELD score is ≥20. The MELD score can be calculated on handheld devices using the laboratory values of international normalized ratio (INR), serum creatinine, and serum bilirubin. The INR used in the MELD score is more reproducible than the prothrombin time (used in the MDF score) which varies based on the sensitivity of the thromboplastin reagent used. MELD-Na is not more accurate than the MELD score since it is likely the hyponatremia in AH is more related to “beer-potomania” than a reflection of the hepatic hemodynamic state of AH.64 An MELD score of ≥20 is associated with 20% mortality at 90 days, and is the threshold for diagnosis of severe AH.65 A MELD score of 11–20 is used to diagnose patients with moderately severe hepatitis. Risk of mortality in patients with MELD score ≤11 is negligible, and these patients are classified as having mild AH.

The MDF has been extensively validated with a score of ≥32 predicting mortality of over 50%.63 MDF is calculated as 4.6 times (prothrombin time minus control) X serum bilirubin (mg/dl). The score is especially useful to select patients for steroid treatment. Typically, only patients with an MDF ≥32 are considered for steroid treatment, given the significant side effects related to steroids. However, there is a lower but still important risk of death in patients with MDF <32. Moreover, the MDF has not been used or cannot be used to assess response to treatment.

The Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score uses age, white cell count, urea, prothrombin ratio or INR, and serum bilirubin.66 A value between 5 and 12 is obtained with a score ≥9 predicting a poor outcome. The ABIC (age, bilirubin, INR, and creatinine) is a modification of the MELD score and also uses categorical variables.67 An ABIC score >9 is associated with approximately 80% mortality at 90 days whereas an ABIC score <6.71 is associated with negligible mortality. As with all scores using categorical variables, minor changes in the score can result in patients being wrongly classified and at higher risk of mortality. A recent study comparing nine predictable models in AH demonstrated that the MELD score was superior to all other scores in determining 30-day mortality as well as 90day mortality.68 The presence of SIRS during hospitalisation may also predict poor outcome.21 Serum markers such as LPS, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein can predict multiorgan failure and death in AH.21

The Lille score used to assess response to corticosteroids as described earlier, also predicts mortality. For example, patients with a Lille score of <0.16 have less than 10% mortality at 28 days whereas those with a Lille score >0.56 have a 50% mortality rate at 28 days. A dynamic model with a combination of MELD score at baseline and Lille score at seven days performs better than a combination of any two scores in predicting mortality at two and six months.69 On the one hand, a patient with an MELD score of 30 at baseline and a Lille score of 0.15 only has a 10% risk of mortality at two months and an approximately 20% risk of mortality at six months. On the other hand, a patient with an MELD score of 30 at baseline and a Lille score of 0.5 has a 28% mortality at two months and an approximately 50% risk of mortality at six months.

Mortality beyond six months is dependent on sustained abstinence from alcohol.41,70 Patients that are steroid responders, as determined by a Lille score <0.45 and are abstinent do well in the long run with a low risk of mortality. Patients who do not respond to steroids but remain abstinent have an intermediate prognosis and may be considered for LT. Meanwhile, steroid non-responders who continue to use alcohol have a high risk of mortality. Such patients are not appropriate candidates for liver transplantation and only palliative care may be offered in these cases.

V. Should liver transplantation have been carried out?

Early liver transplantation in alcoholic hepatitis

Patients who are steroid responders, as determined by a Lille score <0.45 and are abstinent, do well in the long run with a low risk of mortality. Among those patients who survive an episode of severe AH but relapse to alcohol use or continue to drink, liver transplantation is not appropriate unless they can establish secure abstinence, in the absence of which, palliative care is often the only recourse in instances of life-threatening deterioration. Abstinence from alcohol use for at least six months is a requirement in most transplant centres before listing patients with end-stage liver disease of any aetiology, including alcohol-related liver disease, for LT.71,72 However, many patients with severe AH who are not responsive to corticosteroids are at high risk of mortality during this six-month waiting period.5,73 Further, six months of abstinence is not a strong and consistent predictor of relapse to alcohol use after transplantation. Other factors such as psychosocial status, polysubstance use, and younger age are more robust and consistent predictors of relapse to alcohol use after LT.74

In a prospective pilot study, early LT in 26 select patients with severe AH (median time of 13 days to listing from documentation of nonresponse to corticosteroids) was compared to standard of care in 26 patients with severe AH who were not eligible for LT. Patients with a first episode of AH non-responsive to steroid therapy who had excellent psychosocial support and agreed to sign a contract on commitment to lifelong alcohol abstinence were selected for early LT. There was a survival benefit at six months among the transplanted patients (77 vs. 23%, p <0.001) after LT.75 Three of 26 patients relapsed to alcohol use (only one with heavy alcohol use) during the following three years. Since that report many retrospective and prospective studies have confirmed benefits of early LT in select patients with AH,76–78 with risk for relapse to alcohol use similar to that observed after transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis.79

In spite of these encouraging data, there have been barriers to accepting liver transplantation for selected patients with severe AH.77 Living donor LT is an option to overcome the barrier of donor shortage, with outcomes comparable to LT using deceased donors. However, rigorous criteria should be used to select recipients, irrespective of the type of donor used.80 If used in carefully selected patients, early LT while using only about 1.5–3% of the donor pool could provide survival benefit to AH patients facing a risk of high mortality in their most productive period of life.75,76,78 Another concern is the high mortality of 23% within the first six months reported in the prospective French-Belgian study,75 compared to the expected one-year mortality of less than 5% after LT for alcohol-related cirrhosis.71 The majority of deaths in the Mathurin study were due to invasive fungal infections associated with steroid use.75 Clearly, steroids should be stopped as soon as it is apparent there is no response to therapy, perhaps as early as four days after initiation. There is also a need to develop uniform criteria for selection of patients with severe AH for early LT, especially considering living donor transplantation, and a uniform protocol for their post-transplant follow-up and management.

Back to clinical vignette and recommendations

I. Should liver biopsy have been carried out inthis patient before starting treatment for alcoholic hepatitis?

This patient had two episodes of AH. In the first episode, the patient met criteria for clinical diagnosis or “Probable AH”, with chronic active heavy alcohol use; AST >ALT by >1.5:1, with AST >50 and less than 400–500 IU/L, serum bilirubin >3 mg/dl; and absence of other causes of liver disease. Based on these criteria, the patient was diagnosed as AH and could be appropriately treated as AH without having to undergo a liver biopsy.

II. What should the protocol be for early diagnosis of infection?

There is no evidence-based protocol for early diagnosis of infection in patients with AH. High circulating 16s bacterial DNA levels can identify patients at risk of infections on prednisolone therapy, but this test is not available for use outside of investigational studies. All patients with severe AH should have blood cultures, urine culture, chest X-ray, and ascitic fluid examination), in those being considered for steroid therapy. There are currently no data on the role of adjuvant antibiotics with corticosteroids in preventing infections and improvement of patient outcome. The role of routine antibiotic therapy awaits the results of an ongoing clinical trial. When sepsis is strongly suspected, and certainly when infection is diagnosed, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated within one hour.

III. Are there options other than steroid therapy for severe AH? Should pharmacological therapy have been initiated to prevent alcohol relapse?

Patients with severe AH need two physicians for optimal care, a hepatologist and an addiction specialist. Current data do not suggest any agent other than steroids be used outside of clinical trials to treat severe AH. An addiction specialist reduces the risk of relapse to alcohol use among survivors of the index episode of AH.86 Patients with AH often return to drinking once they get better. For example, only 45% and 37% of one month survivors in the STOPAH study were abstinent from alcohol at six months and at one year from the initial presentation with AH, respectively.43 This patient was appropriately evaluated by an addiction specialist during the first hospitalisation, and was transitioned to an inpatient rehabilitation programme. However, he relapsed to alcohol use three months later. Whether adjuvant pharmacological therapy such as baclofen should have been initiated remains an unanswered question. Baclofen in most randomised studies has shown benefit which is limited to short-term.59 We do not routinely use baclofen in patients recovering from AH. However, it would not have been unreasonable to start baclofen in a dose of 5 mg three times daily, slowly increased over 7–10 days to maximum dose of 15 mg three times daily.

IV. What are the determinants of short-term and long-term prognosis in alcoholic hepatitis?

At the initial admission, the MELD score was 24 which is associated with a three-month mortality of 40%. Given the favourable Lille score of 0.4 at seven days, his predicted two-month mortality was calculated to be 18% and six-month mortality 26%. That is, steroid therapy reduced his mortality risk. At the second admission the MELD score was 32 and the Lille score 0.6. The predicted twomonth mortality would have been 38% and the six-month mortality, 55%.

V. Should early liver transplantation have been carried out?

According to the social history, the patient is married, has a child, and his wife and siblings are attentive and present in his life suggesting good social support. However, he failed to establish abstinence after his previous episode of AH. The young age and relapse to drinking within three months of completing inpatient rehabilitation treatment following a prior episode of severe AH puts him at a very high risk for relapse to alcohol use after LT. The addiction specialist too considered him at high risk for relapse. According to the protocol of the French-Belgian landmark study, the patient described in the clinical vignette would not have been considered an appropriate candidate for early LT,75 and therefore LT was not considered in this patient, when he presented with second episode of severe AH.

Key point.

Liver biopsy is recommended for diagnosis because up to 30% of patients with a clinical diagnosis of AH may have their diagnosis changed after biopsy.

Key point.

Post hoc analysis of the STOPAH trial suggested that some patients had subclinical infection before the initiation of prednisolone, highlighting the need for systematic screening.

Key point.

There is promising data on a number of alternative treatments for AH, including growth factors and faecal microbiota transplantation, although further studies are required.

Key point.

There is a need to develop uniform criteria for selecting patients with severe AH for LT, with a particular focus on living donor transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

The work was supported by the NIAAA 21788 grant to PSK and VHS, and NIAAA 023273 grant to AKS.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.001.

References

- [1].Crabb DW, Bataller R, Chalasani NP, Kamath PS, Lucey M, Mathurin P, et al. Standard definitions and common data elements for clinical trials in patients with alcoholic hepatitis: recommendation from the NIAAA alcoholic hepatitis consortia. Gastroenterology 2016;150:785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2012;57:399–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hardy T, Wells C, Kendrick S, Hudson M, Day CP, Burt AD, et al. White cell count and platelet count associate with histological alcoholic hepatitis in jaundiced harmful drinkers. BMC Gastroenterol 2013;13:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mookerjee RP, Lackner C, Stauber R, Stadlbauer V, Deheragoda M, Aigelsreiter A, et al. The role of liver biopsy in the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with acute deterioration of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2011;55:1103–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2758–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Singal AK, Kodali S, Vucovich LA, Darley-Usmar V, Schiano TD. Diagnosis and treatment of alcoholic hepatitis: a systematic review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016;40:1390–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kalambokis G, Manousou P, Vibhakorn S, Marelli L, Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy–indications, adequacy, quality of specimens, and complications–a systematic review. J Hepatol 2007;47:284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2017;377:756–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Altamirano J, Miquel R, Katoonizadeh A, Abraldes JG, Duarte-Rojo A, Louvet A, et al. A histologic scoring system for prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1231–1239, e1231–e1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bissonnette J, Altamirano J, Devue C, Roux O, Payance A, Lebrec D, et al. A prospective study of the utility of plasma biomarkers to diagnose alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2017;66:555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mueller S, Peccerella T, Qin H, Glassen K, Waldherr R, Flechtenmacher C, et al. Carcinogenic etheno-DNA adducts in alcoholic liver disease: correlation with cytochrome P-4502E1 and fibrosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2018;42:252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Singal AK, Chacko B, Darley-Usmar V. A promising biomarker in management of patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2017;66:92A. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chacko BK, Kramer PA, Ravi S, Benavides GA, Mitchell T, Dranka BP, et al. The Bioenergetic Health Index: a new concept in mitochondrial translational research. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;127:367–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Betrapally NS, Gillevet PM, Bajaj JS, et al. Changes in the intestinal microbiome and alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver diseases: causes or effects? Gastroenterology 2016;150:1745–1755, e1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Singal AK, Kamath PS, Gores GJ, Shah VH. Alcoholic hepatitis: current challenges and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:555–564, [quiz e531–e552]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang AM, Inamine T, Hochrath K, Chen P, Wang L, Llorente C, et al. Intestinal fungi contribute to development of alcoholic liver disease. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2829–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Keshavarzian A, Fields JZ, Vaeth J, Holmes EW. The differing effects of acute and chronic alcohol on gastric and intestinal permeability. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:2205–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Szabo G, Petrasek J. Inflammasome activation and function in liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McClain C, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S, Song Z, Deaciuc I, Chen T, et al. Dysregulated cytokine metabolism, altered hepatic methionine metabolism and proteasome dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:180S–188S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, Dharancy S, Hollebecque A, Canva-Delcambre V, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology 2009;137:541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Michelena J, Altamirano J, Abraldes JG, Affo S, Morales-Ibanez O, Sancho-Bru P, et al. Systemic inflammatory response and serum lipopolysaccharide levels predict multiple organ failure and death in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2015;62:762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hmoud BS, Patel K, Bataller R, Singal AK. Corticosteroids and occurrence of and mortality from infections in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Liver Int 2016;36:721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Louvet A Restoration of bactericidal activity of neutrophils by myeloperoxidase release: a new perspective for preventing infection in alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2016;64:1006–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vergis N, Khamri W, Beale K, Sadiq F, Aletrari MO, Moore C, et al. Defective monocyte oxidative burst predicts infection in alcoholic hepatitis and is associated with reduced expression of NADPH oxidase. Gut 2017;66:519–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mookerjee RP, Stadlbauer V, Lidder S, Wright GA, Hodges SJ, Davies NA, et al. Neutrophil dysfunction in alcoholic hepatitis superimposed on cirrhosis is reversible and predicts the outcome. Hepatology 2007;46:831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Boussif A, Rolas L, Weiss E, Bouriche H, Moreau R, Perianin A. Impaired intracellular signaling, myeloperoxidase release and bactericidal activity of neutrophils from patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2016;64:1041–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Markwick LJ, Riva A, Ryan JM, Cooksley H, Palma E, Tranah TH, et al. Blockade of PD1 and TIM3 restores innate and adaptive immunity in patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015;148:590–602, e510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gustot T, Fernandez J, Szabo G, Albillos A, Louvet A, Jalan R, et al. Sepsis in alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol 2017;67:1031–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Singal AK, Shah VH, Kamath PS. Infection in severe alcoholic hepatitis: yet another piece in the puzzle. Gastroenterology 2017;152:938–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Biggins SW, Patton H, et al. Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology 2014;60:250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cervoni JP, Thevenot T, Weil D, Muel E, Barbot O, Sheppard F, et al. C-reactive protein predicts short-term mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2012;56:1299–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vergis N, Atkinson SR, Knapp S, Maurice J, Allison M, Austin A, et al. In patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, prednisolone increases susceptibility to infection and infection-related mortality, and is associated with high circulating levels of bacterial DNA. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1068–1077, e1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Louvet A, Mathurin P. Alcoholic liver disease: mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Franchimont D Overview of the actions of glucocorticoids on the immune response: a good model to characterize new pathways of immunosuppression for new treatment strategies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004;1024:124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Singal AK, Salameh H, Singal A, Jampana SC, Freeman DH, Anderson KE, et al. Management practices of hepatitis C virus infected alcoholic hepatitis patients: a survey of physicians. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2013;4:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ahn JMT, Cohen SM. Evaluation and management of alcoholic hepatitis: a survey of current practices. Hepatology 2009:612A.19575456 [Google Scholar]

- [38].Singal AK, Walia I, Singal A, Soloway RD. Corticosteroids and pentoxifylline for the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis: current status. World J Hepatol 2011;3:205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gustot T, Maillart E, Bocci M, Surin R, Trepo E, Degre D, et al. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 2014;60:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Diaz E, Fartoux L, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology 2007;45:1348–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Altamirano J, Lopez-Pelayo H, Michelena J, Jones PD, Ortega L, Gines P, et al. Alcohol abstinence in patients surviving an episode of alcoholic hepatitis: prediction and impact on long-term survival. Hepatology 2017;66:1842–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].McClain CJ, Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 1989;9:349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Thursz MR, Forrest EH, Ryder SSTOPAH investigators. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:282–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, Coevoet H, Texier F, Thevenot T, et al. Early switch to pentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol 2008;48:465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mathurin P, Louvet A, Duhamel A, Nahon P, Carbonell N, Boursier J, et al. Prednisolone with vs. without pentoxifylline and survival of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nguyen-Khac E, Thevenot T, Piquet MA, Benferhat S, Goria O, Chatelain D, et al. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1781–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Naveau S, Chollet-Martin S, Dharancy S, Mathurin P, Jouet P, Piquet MA, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of infliximab associated with prednisolone in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2004;39:1390–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Boetticher NC, Peine CJ, Kwo P, Abrams GA, Patel T, Aqel B, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of etanercept in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1953–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Singal AK, Jampana SC, Weinman SA. Antioxidants as therapeutic agents for liver disease. Liver Int 2011;31:1432–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Trinchet JC, Balkau B, Poupon RE, Heintzmann F, Callard P, Gotheil C, et al. Treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis by infusion of insulin and glucagon: a multicenter sequential trial. Hepatology 1992;15:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Rambaldi A, Iaquinto G, Gluud C. Anabolic-androgenic steroids for alcoholic liver disease: a Cochrane review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1674–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Orrego H, Israel Y. Propylthiouracil treatment for alcoholic hepatitis: the case of the missing thirty. Gastroenterology 1982;83:945–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Banares R, Nevens F, Larsen FS, Jalan R, Albillos A, Dollinger M, et al. Extracorporeal albumin dialysis with the molecular adsorbent recirculating system in acute-on-chronic liver failure: the RELIEF trial. Hepatology 2013;57:1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Singh S, Murad MH, Chandar AK, Bongiorno CM, Singal AK, Atkinson SR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for severe alcoholic hepatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:958–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG clinical guideline: alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, [In press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mathurin P, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Carbonell N, Fartoux L, Serfaty L, et al. Early change in bilirubin levels is an important prognostic factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with prednisolone. Hepatology 2003;38:1363–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gustot T, Fernandez J, Garcia E, Morando F, Caraceni P, Alessandria C, et al. Clinical Course of acute-on-chronic liver failure syndrome and effects on prognosis. Hepatology 2015;62:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Babineaux MJ, Anand BS. General aspects of the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. World J Hepatol 2011;3:125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet 2007;370:1915–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Garcia-Saenz-de-Sicilia M, Duvoor C, Altamirano J, Chavez-Araujo R, Prado V, de Lourdes Cando-Martinelli A, et al. A day-4 Lille model predicts response to corticosteroids and mortality in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:306–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mathurin P, Beuzin F, Louvet A, Carrie-Ganne N, Balian A, Trinchet JC, et al. Fibrosis progression occurs in a subgroup of heavy drinkers with typical histological features. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:1047–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001;33:464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL Jr, Mezey E, White RI Jr. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1978;75:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Vaa BE, Asrani SK, Dunn W, Kamath PS, Shah VH. Influence of serum sodium on MELD-based survival prediction in alcoholic hepatitis. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, Wiesner RH, Kim WR, Menon KV, et al. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2005;41:353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Forrest EH, Evans CD, Stewart S, Phillips M, Oo YH, McAvoy NC, et al. Analysis of factors predictive of mortality in alcoholic hepatitis and derivation and validation of the Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score. Gut 2005;54:1174–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Dominguez M, Rincon D, Abraldes JG, Miquel R, Colmenero J, Bellot P, et al. A new scoring system for prognostic stratification of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2747–2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Papastergiou V, Tsochatzis EA, Pieri G, Thalassinos E, Dhar A, Bruno S, et al. Nine scoring models for short-term mortality in alcoholic hepatitis: cross-validation in a biopsy-proven cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:721–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Louvet A, Labreuche J, Artru F, Boursier J, Kim DJ, O’Grady J, et al. Combining data from liver disease scoring systems better predicts outcomes of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Louvet A, Labreuche J, Artru F, Bouthors A, Rolland B, Saffers P, et al. Main drivers of outcome differ between short term and long term in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a prospective study. Hepatology 2017;66:1464–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology 2014;59:1144–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Russ KB, Chen NW, Kamath PS, Shah VH, Kuo YF, Singal AK. Alcohol use after liver transplantation is independent of liver disease etiology. Alcohol Alcohol 2016;51:698–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Singal AK, Jampana SC. Current management of alcoholic liver disease. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7:18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].McCallum S, Masterton G. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a systematic review of psychosocial selection criteria. Alcohol Alcohol 2006;41:358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, Dumortier J, Salleron J, Durand F, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1790–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Singal AK, Bashar H, Anand BS, Jampana SC, Singal V, Kuo YF. Outcomes after liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis are similar to alcoholic cirrhosis: exploratory analysis from the UNOS database. Hepatology 2012;55:1398–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hasanin M, Dubay DA, McGuire BM, Schiano T, Singal AK. Liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis: a survey of liver transplant centers. Liver Transpl 2015;21:1449–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Im GY, Kim-Schluger L, Shenoy A, Schubert E, Goel A, Friedman SL, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis in the united states-a singlecenter experience. Am J Transplant 2016;16:841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Switzer GE, Kormos RL, Schulberg HC, Roth LH, et al. Patterns and predictors of risk for depressive and anxiety-related disorders during the first three years after heart transplantation. Psychosomatics 2000;41:191–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Singal AK, Kamath PS. Live donor liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatol Int 2017;11:34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02281929.

- [82].https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01912404.

- [83].https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01809132.

- [84].Kedarisetty CK, Anand L, Bhardwaj A, Bhadoria AS, Kumar G, Vyas AK, et al. Combination of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and erythropoietin improves outcomes of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1362–1370, e1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Philips CA, Pande A, Shasthry SM, Jamwal KD, Khillan V, Chandel SS, et al. Healthy donor fecal microbiota transplantation in steroid-ineligible severe alcoholic hepatitis: a pilot study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:600–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Singal AK, Shah VH. Therapeutic strategies for the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis 2016;36:56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]