Abstract

Using retrospective union, birth, and education histories that span 1980–2003, this study investigates nonmarital childbearing in contemporary Russia. We employ a combination of methods to decompose fertility rates by union status and analyze the processes that lead to a nonmarital birth. We find that the increase in the percentage of nonmarital births was driven mainly by the growing proportion of women who cohabit before conception, not changing fertility behavior of cohabitors or changes in union behavior after conception. The relationship between education and nonmarital childbearing has remained stable: the least-educated women have the highest birth rates within cohabitation and as single mothers, primarily because of their lower probability of legitimating a nonmarital conception. These findings suggest that nonmarital childbearing Russia has more in common with the pattern of disadvantage in the United States than with the second demographic transition. We also find several aspects of nonmarital childbearing that neither of these perspectives anticipates.

Keywords: Nonmarital childbearing, Cohabitation, Fertility, Single mothers, Russia

Introduction

Many demographers consider nonmarital childbearing a definitive characteristic of the “second demographic transition” (Lesthaeghe and Neidert 2006; McLanahan 2004; Sobotka et al. 2003; Surkyn and Lesthaeghe 2004). However, the circumstances leading to, and consequences of, nonmarital childbearing vary greatly depending on context. In Europe, particularly the Scandinavian countries, nonmarital childbearing primarily occurs among stable, cohabiting couples (Kiernan 2004; Perelli-Harris et al. 2009).1 In the United States, however, nonmarital childbearing is more often associated with a pattern of disadvantage experienced by single mothers and low-income minority populations (Edin and Kefalas 2005; Wu and Wolfe 2001). Moreover, the unions of cohabiting couples who have children in the United States tend to be less stable than marital unions (Wu and Wolfe 2001). Thus, although nonmarital childbearing in northern Europe signifies a rejection of traditional institutions and an increase in independence and autonomy, nonmarital childbearing in the United States is associated with socioeconomic hardship and obstacles to marriage.

We investigate the dramatic growth of nonmarital childbearing in contemporary Russia, where the percentage of nonmarital births grew from 14.6% in 1990 to 29.8% in 2004, according to official data (Zakharov et al. 2005). Using rich survey data with complete union and fertility histories, we shed new light on the processes that produced this change by addressing these questions: Is the surge in nonmarital childbearing mainly attributable to increasing nonmarital fertility rates or to the decreasing fertility of married women? Have births to cohabiting women and single women followed similar trends? What roles do the intermediate steps in the process—conception and union formation after conception—play in the rate of nonmarital childbearing? Finally, how is education related to nonmarital childbearing?

Nonmarital childbearing has increased in many countries, but Russia provides a particularly interesting case study because of the vast changes that occurred during and after the breakup of the Soviet Union. As we detail in the following sections, these changes could have led to either the second demographic transition (SDT) or the U.S. pattern of disadvantage (POD). We adjudicate between these two alternative accounts of nonmarital childbearing in Russia by distinguishing births to single women from births to cohabiting women, estimating how the rates of each type of birth vary over time and across education levels, and conducting separate analyses of two key phases in the process that leads to different types of births (conception and legitimation). Of course, multiple patterns of cohabitation—and family formation, more generally—coexist in modern societies (Roussel 1989). By testing whether Russia fits the SDT or POD account more closely, we mean only to address which model best captures the detailed trends and correlates of nonmarital childbearing, not to claim that either account could possibly explain all of its instances. We find that although Russia shares some aspects of SDT theory, it has more features similar to the POD. Moreover, several aspects of nonmarital fertility in contemporary Russia fit neither of these general perspectives.

Theoretical Framework

Second Demographic Transition (SDT)

Proponents of SDT theory consider nonmarital childbearing to be one of its signature elements (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002; van de Kaa 2001). In its most basic conceptualization, the SDT refers to a package of interconnected behaviors, including cohabitation, declines or delays in marriage, postponement of childbearing, and below-replacement levels of fertility (Lesthaeghe and Neidert 2006; McLanahan 2004; Sobotka et al. 2003). Dirk van de Kaa (2001) further specified that the behavioral changes of the SDT occur in a sequence, starting with declines in the total fertility rate and progressing through 15 stages that culminate in the decoupling of marriage and fertility. Over time, cohabitating unions become more stable, and the fertility behaviors of cohabiting and married couples converge, with fewer pregnancies to cohabiting couples prompting marriage (Raley 2001). With respect to fertility behavior, cohabitation becomes an “alternative to marriage” (Manning 1993). These arguments imply that childbearing becomes more common within cohabiting unions not sanctioned by formal state or religious institutions, but they do not imply that single motherhood increases.

Other conceptions of the SDT see changes in family formation behavior as the manifestation of new lifestyle choices related to ideational and cultural change, such as an increased emphasis on individual autonomy, rejection of authority, and the rise of values connected to the “higher-order needs” of self-actualization (Lesthaeghe and Neidert 2006; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002; Sobotka et al. 2003). Lesthaeghe and associates (Lesthaeghe and Neidert 2006; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002) and van de Kaa (2001) drew connections to Ronald Inglehart’s (1990) theory of post-materialism, which posits that values change as material needs are met, not only through economic development, but also through investments in education. Indeed, research based on Inglehart’s World Values Survey shows that individuals with higher education are more committed to individualism and gender equality and are less supportive of authority (Weakliem 2002). Thus, although the SDT is not explicitly a model of how education leads to changes in family behavior, education can be used as a proxy for ideational change, with the most highly educated women being the first to adopt the new behaviors associated with the SDT (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002). Finally, by providing women with higher earning potential, higher education may make it possible for women to afford having children without the economic support of a husband.2

Some researchers have argued that Russia, which maintained traditional family formation patterns for most of the Soviet era, embarked on its own version of the SDT in the late 1980s or early 1990s (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002; Vishnevsky 1996; Zakharov 2008); increasing percentages of nonmarital births are cited as key evidence of this development (Zakharov 2008). These studies have claimed that with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russians have become more “Westernized” through ideational change as young people have become more exposed to the values and beliefs of capitalist consumer-oriented countries. These arguments imply that in Russia, education should be associated with nonmarital childbearing because education is one of the main mechanisms leading to the changes in values and beliefs. Women with higher education should be the forerunners of the SDT and thus should be more likely to have children within cohabiting unions.

The account of nonmarital childbearing in Russia derived from SDT theory implies two broad propositions that we can test with our data:

SDT Proposition 1

The increase in nonmarital childbearing stems primarily from an increase in the rate of births to women in nonmarital cohabitation. This follows from Raley’s (2001) interpretation of the SDT: fertility behavior within cohabiting unions becomes more similar to that of married couples. The SDT predicts that single women will increasingly cohabit (rather than marry) in response to a pregnancy, and cohabiting women will be less likely to marry after conceiving a child. Thus, cohabitation will become an “alternative to marriage,” in that pregnancy no longer prompts marriage (Manning 1993).

SDT Proposition 2

Because it is linked to new norms associated with the SDT, high education is positively associated with rates of nonmarital childbearing—particularly childbearing within cohabitation, but also single motherhood.

Pattern of Disadvantage (POD)

In stark contrast to SDT Proposition 2, studies of the United States have consistently shown a negative association between nonmarital childbearing and education, regardless of whether the births occur to single mothers or to cohabiting couples (Rindfuss et al. 1996; Upchurch et al. 2002). Low education is a well-established cause and consequence of material disadvantage, and single and cohabiting unmarried mothers in the United States have higher rates of poverty and welfare dependency (Lichter et al. 2003). As Edin and Kefalas (2005) showed in their extensive qualitative study, two related mechanisms produce this association between disadvantage and nonmarital childbearing: poor women often choose to have a child as a way to provide meaning in their lives, but they see their romantic partners as economically or socially unsuitable for marriage (see also Anderson 1990). In addition, nonmarital childbearing in the United States has been characterized by a high proportion of out-of-wedlock births to teenagers; in the 1970s, 50% of nonmarital births were to women younger than age 20 (Ventura 2009). This age pattern, however, has changed in recent years; in 2007, only 23% of nonmarital births were to women younger than age 20. Thus, we define the pattern of disadvantage as associated with low education and not necessarily with teenage fertility.

Although nonmarital childbearing in the United States is often associated with single motherhood, 40% of nonmarital births in 1995 occurred within cohabiting unions, and the increase in the proportion of nonmarital births during the 1990s stemmed largely from births to cohabiting couples (Bumpass and Lu 2000). Most evidence, however, indicates that cohabitation is not becoming an alternative to marriage (Raley 2001). Compared with married couples, cohabitors in the United States are more likely to end their union (Brines and Joyner 1999), especially after a first birth (Wu et al. 2001); express unhappiness with their current situation (Brown and Booth 1996); and experience physical violence and emotional abuse (Kenney and McLanahan 2006). These findings suggest that cohabitation in the United States tends to be an arrangement of economic necessity or unstable relationships and not, as Lesthaeghe and Neidert (2006) suggested, a normative choice reflecting the spread of “higher-order” values associated with the SDT.3

Russia could well resemble the United States in terms of nonmarital childbearing being practiced by the least educated and most socially disadvantaged. Russia’s economic turmoil of the 1990s led to increases in unemployment, poverty, stratification, and general economic instability (Gerber 2002; Gerber and Hout 1998). Correspondingly, Russian women at the bottom of the social hierarchy may be especially likely to turn to childbearing as a way to find meaning in their lives, even as the pool of marriageable men available to them has dwindled. As in the United States, male unemployment or the lack of financial resources may be acting as a barrier to marriage or a wedding ceremony (Edin and Kefalas 2005), especially as cohabitation becomes more acceptable. Indeed, studies have shown that single-parent families in Russia disproportionately suffered during the transition to a new economy (Klugman and Motivans 2001; Mroz and Popkin 1995). In addition, an increase in anomie, or breakdown in social norms, could be leading to an increase in risky behavior (such as unprotected sex) or other negative outcomes (such as lower marital quality, alcoholism, or spouse abuse) (Perelli-Harris 2006). Russian women are often reluctant to abort a first pregnancy because of fears of infertility and other medical concerns (Perelli-Harris 2005); so in a context of fewer men with the economic and emotional resources to marry, a constant rate of unintended premarital pregnancies would lead to an increase in nonmarital births.

POD Proposition 1

The increase in nonmarital childbearing stems primarily from an increase in the rate of births to single women, which is greater than the increase in births to cohabiting women. The POD perspective does not rule out increasing births within cohabitation, however, because in Russia cohabitating unions are more unstable than marital unions (Muszynska 2008).

POD Proposition 2

Low education, a reliable and consistent proxy for disadvantage, is associated with higher rates of nonmarital childbearing—particularly among single mothers, but also among cohabiting women.

Analytic Strategy

Estimating the Rates of Single, Cohabiting, and Marital Births

Our theoretical discussion emphasizes the distinction between two types of nonmarital first births: to single women and to cohabiting women. Our analyses focus exclusively on first births, which comprise about 66% of all nonmarital births. Because nonmarital births are more likely to occur at parity 0 than at higher parities, an analysis of first births provides the clearest picture of trends and correlates of nonmarital childbearing. Also, including higher-order births in our analysis would risk conflating trends in parity and spacing with trends in nonmarital births.

First, we estimate the monthly rates of each of these three types of first births, defined simply as the number of first births of each type occurring during a given month divided by the number of women at risk of any first birth at the start of that month. The raw rates of single, cohabiting, and marital births provide more information than the percentages of births by union status because all three birth rates vary independently, while only two of the three percentages do. Furthermore, the rates directly measure different types of fertility behavior, but the percentages indicate only the relationships of each rate to the other two rates. In fact, the percentages can easily be derived from the rates.4 However, the opposite is not the case: for example, increasing percentages over time of single births do not necessarily imply that the single births are occurring more frequently. They could even be occurring less frequently, as long as the rate of marital births is decreasing more rapidly. The same goes for variation in percentages versus rates by levels of education.

The three birth rates of interest are equivalent to three competing risks, which we model in a discrete-time framework by estimating multinomial logistic regressions (MLR), using the sample of all person-months when childbearingage respondents were at risk for having a first birth. The basic form of the model is

| (1) |

where h(m)it denotes the hazard that respondent i will experience event m in month t, which is equivalent to the probability that i has the value m on a nominal variable y at the end of month t. There are four categories of y: a single birth, cohabiting birth, marital birth, and no birth in month t. The xijt represent respondent i’s values on a set of j potentially time-varying covariates at time t. The βjm are parameters estimated from the data using maximum likelihood. The m subscript on βjm shows that a separate parameter vector is estimated for each possible type of event. The model is identified by constraining all the elements in one such vector to equal zero (e.g., βj1=0). The choice of such a “baseline” category of m is arbitrary. The lack of a t subscript on βjm indicates that the coefficients do not vary over time, but we test for change over time in the effects of covariates by incorporating the appropriate interaction terms as xj.

We estimate two versions of the model. The first includes only age and period as covariates. Based on the results of this model, we calculate and plot the age-adjusted period-specific hazard rates for each type of nonmarital birth. The second version of the model introduces dummy variables measuring respondent’s education in the particular month at risk. Based on the results, we calculate and plot separate age-adjusted, period-specific hazards of each type of nonmarital birth for women with different levels of education. These results provide informative descriptions of how nonmarital childbearing rates vary by education and change over time. Even though they are based on a regression model, they are purely descriptive in the sense that we use the model to estimate the unobserved age-adjusted rates during different periods of time and for women at different levels of education.

Steps in the Path to a Nonmarital Birth

As we alluded to earlier, rates of nonmarital first births result from a complex process that can be decomposed into three discrete components: (1) the distribution of childless women of childbearing age across union statuses prior to conceptions; (2) the rates of conception within each union status; and (3) the probabilities of being in each union at the time of birth, conditional on union status at time of conception.5 Each discrete component may exhibit a distinct trend and relationship to education. For example, an increase in the proportion of childbearing-age women who are in cohabiting relationships or who are single (either because they have never married or because they have divorced) would increase the rate of nonmarital births even without any change in the fertility behaviors typical of each union status: Russia’s retreat from marriage and increasing cohabitation, which are analyzed elsewhere (Gerber and Berman 2010; Hoem et al. 2009; Zakharov 2008), could be the main factor behind the increasing proportions of nonmarital births.

Alternatively, fertility behavior within union status can change. Russian observers have documented a “sexual revolution” that started in the 1980s and developed with full force in the early 1990s (see Kon 1995). These changes in sexual behavior could easily have increased the rate of unintended pregnancies among single and cohabiting women, although they would not have that effect if, for example, the increased sexual activity was accompanied by an increased use in contraception. Sexual behavior and contraception usage could well vary by education in Russia: Gerber and Berman (2008) found that university-educated women are more likely to use condoms.

Finally, greater normative acceptance of nonmarital childbearing could lessen the social pressure to legitimize nonmarital conceptions prior to birth. In fact, shotgun marriages were unusually common in Soviet Russia (Cartwright 2000). According to the Russian Generations and Gender Survey (GGS), in the early 1980s, 46% of pregnancies that started out of wedlock (and resulted in a live birth) ended with a marital birth. This percentage declined subsequently but was still at 37% in 2000–2003. This percentage is relatively high compared with percentages in the United States: for example, 45% of premarital conceptions in the United States were legitimated in the 1970s (Manning 1993), but by the 1990s, only 19% were legitimated (Upchurch et al. 2002). Therefore, decreased normative insistence on marriage as a prerequisite to childbearing could well have a profound effect on the probabilities of union status at birth following a single or cohabiting conception.

Ideally, we might attempt to model the entire set of these transitions jointly by using simultaneous hazard equations with correlated residuals across equations, as researchers have previously done for subsets of transitions (Brien et al. 1999; Musick 2007; Steele et al. 2006; Upchurch et al. 2002). However, modeling all the processes simultaneously poses computational challenges and places strong demands on the data, particularly because some of the transitions occur at very low rates. Moreover, we can achieve our primary goal of providing an empirically based account of change over time in nonmarital childbearing patterns of Russian women with different levels of education in order to see whether Russia fits the SDT or the POD model by separately estimating models for a limited set of the transitions.

We do not analyze changes in union status prior to first conception in this article because others have examined trends in union formation behavior and its correlates in Russia (Gerber and Berman 2010; Hoem et al. 2009, Kostova 2007; Philipov and Jasiloniene 2008). These studies have demonstrated a steady increase in cohabitation entry rates beginning in the early 1980s, as well as a decline in marriage entry rates, both of which are trends consistent with SDT Proposition 1. However, these studies also have reported a significant positive effect of education on marriage entry rates, which contradicts SDT Proposition 2 and confirms POD Proposition 1. Here we treat union status as exogenously given and focus on the two steps pertaining to fertility behavior.

First, we estimate straightforward discrete-time event-history models of first conception rates within each union status. Respondents at risk of first conception enter and exit the risk sets for conception within each union status whenever they change their union status. Although our hypotheses focus on conception rates of women who are single and cohabiting, we also estimate models of conception among married women for the sake of comparison and completeness.

Next, we analyze the probability of each union status at the time of birth following conceptions to single and cohabiting women. Because the precise timing of changes in union status during pregnancy is less important than the status at time of birth, we estimate simple MLR models for union status at the time of birth for women who were single and cohabiting at the time of conception. The main covariates of interest in these models are education and period, but we also include controls for age, school enrollment, and (where appropriate) duration of partnership.

Data and Measures

Data

Because official statistics do not include information on cohabiting unions at the time of birth, we analyze the Russian GGS.6 The GGS conducted interviews with 7,038 women aged 15–79. The overall response rate was 48%, but comparisons show that the GGS is generally comparable with the Russian census in terms of major population characteristics (Houle and Shkolnikov 2005).7 The GGS has a very low response rate (15%) in the largest urban areas of Russia—Moscow and St. Petersburg—where births within cohabitation could be increasing most quickly among the highly educated. Thus, the survey may not be representative of these major urban areas, where childbearing within cohabitation may be increasing the most quickly. Limitations aside, the GGS is suitable for analyzing fertility and union behavior in Russia because it includes complete retrospective marital and fertility histories, distinguishes between married and unmarried partnerships, and offers ample statistical power for testing hypotheses about trends over time and the associations between fertility and education. It has been widely used in recent demographic analyses of contemporary Russia (Hoem et al. 2009; Kostova 2007; Maleva and Sinyavskaya 2007; Philipov and Jasiloniene 2008; Zakharov 2008).

In order to analyze the rates of first births and first conceptions by union status, we created a spell file in which the observations consist of person-months when respondents were of childbearing age (15–49) and had not yet had a first birth. Conceptions are defined by backdating live births 8 months, when the decision to keep a pregnancy is often made. Unfortunately, this measure means that we cannot identify conceptions that ended in abortions or miscarriages. Also, because we do not know whether respondents were pregnant at the time of the survey, we cannot identify conceptions less than 9 months before that time, so we censor all respondents at the end of 2003. Our results referring to conception pertain only to conceptions that eventually result in a birth and do not take into account changes that may result from declining abortion rates.

Measures

Educational Attainment and Enrollment

We created time-varying measures for educational level and enrollment using three variables: highest level of education attained, date of graduation, and school enrollment at the time of the interview. We assume continuous enrollment until date of graduation and changing attainment at average ages of graduation associated with each particular degree, which we computed from observed responses in the GGS.8 Our initial time-varying measure of highest attainment had five categories, but in all analyses, we found that three suffice: postsecondary (semiprofessional or “specialized” secondary degree, some university, university degree, and graduate degree), secondary (including general secondary diplomas and lower vocational training or professional-technical school), and less than secondary.9

Period

After experimenting with several specifications of calendar year (including linear time and five-year periods), we found that four-year intervals starting in 1980 and ending in 2003 fit best. These periods correspond with social and economic changes: 1980–1983 corresponds to the pre-Gorbachev era (full-blown Soviet system); 1984–1988 marks the start of Gorbachev’s rule and his initial efforts to reform the system; 1988–1991 saw full-fledged perestroika and the institution of family benefits; 1992–1995 witnessed the collapse of the Soviet Union, introduction of radical market reforms, and the onset of economic crisis; the crisis continued despite relative political stability in 1996–1999; and 2000–2003 was a period of strong economic recovery. We use 1996–1999 as the reference category because the economic crisis peaked in late 1998 and fertility was lowest during this period.

Age and Union Duration

Age refers to current age in a particular month. Union duration refers to the number of months since the respondent married or began cohabiting with her current partner. These variables may be correlated with period and education and must be controlled. We tested several specifications of both variables (e.g., second- and third-order polynomials) and report only the specifications that fit best based on likelihood ratio tests. We also tested for change over time in the first-order effects, as described later in this article.

Results

First-Birth Rates by Union Status

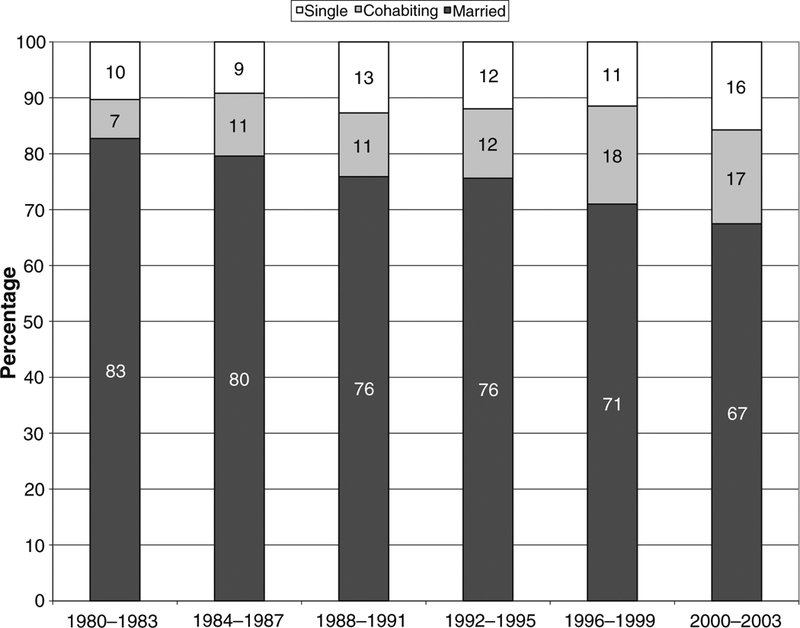

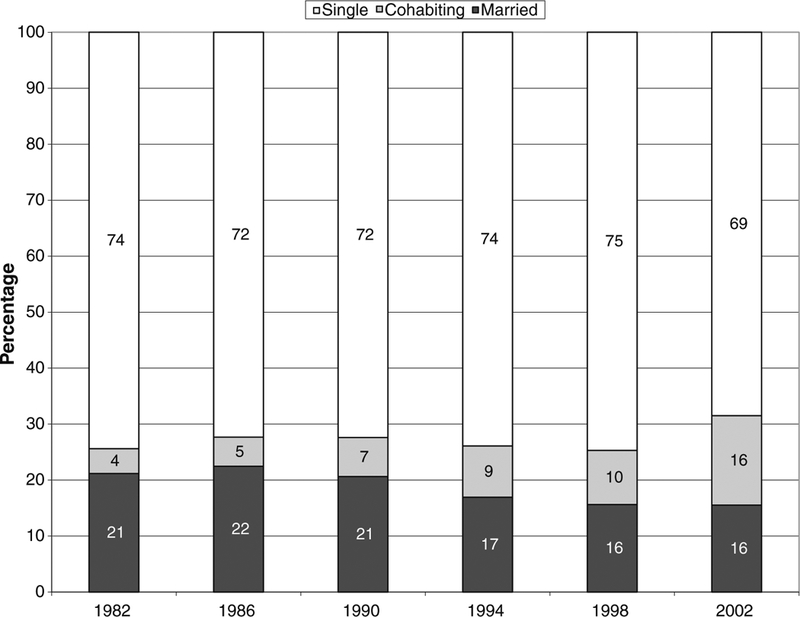

The GGS data reflect the established growth in the percentages of nonmarital first births: it increased steadily from 17% in 1980–1983 to 33% in 2000–2003 (Fig. 1). Until 2000–2003, births within cohabitation accounted for most of the increase in the percentage of nonmarital births, with the percentages of births to single women fluctuating around 11%. In the last period, however, births to single women rose to 16%, while births to cohabiting women remained at 17%.

Fig. 1.

Percentage first births by union status and period: Women aged 15–49

Although Fig. 1 is the conventional way to depict trends in nonmarital fertility, it can be misleading, as discussed earlier. To obtain age-adjusted estimates of the period-specific rates of each type of first birth, we estimated the discrete-time competing risk model, with only age and period as covariates. Using the coefficients estimated from the data, we calculated the expected rates of single, cohabiting, and marital births during each period plotted in Fig. 2.10

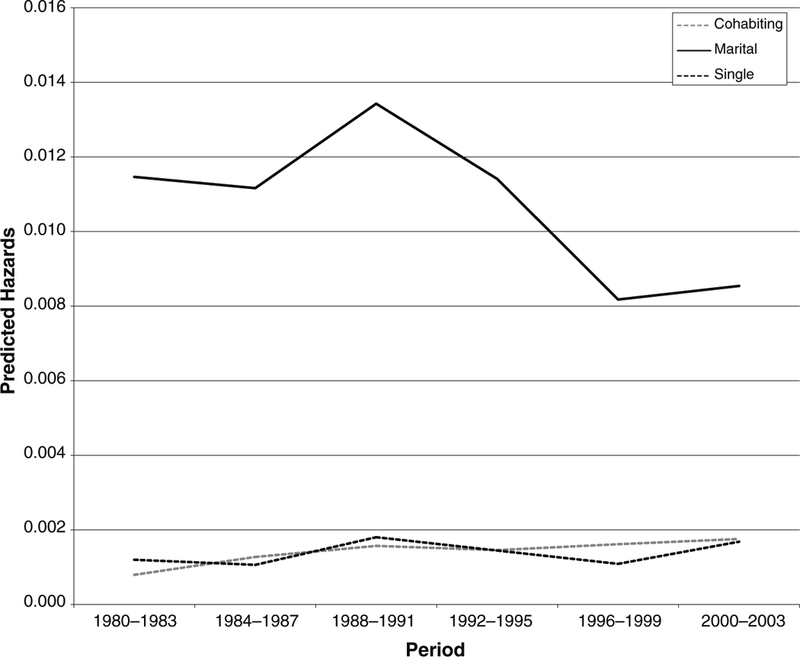

Fig. 2.

Predicted hazards of single, cohabiting, and marital first births, adjusted only for age (estimated at age 22): Women aged 15–49. Data are from the Russian GGS

Figure 2 is far more informative than Fig. 1. It shows that the increase in nonmarital childbearing is due both to the decline in marital birth rates and to the increase in nonmarital birth rates. The rate of marital births increased gradually in the late 1980s, but then fell sharply during the 1990s before stabilizing in the early 2000s. This trend is consistent with other studies of overall fertility in Russia and reflects changes in family policies in the late 1980s, economic turmoil in the 1990s, and the resurgent Russian economy in the early 2000s (Zakharov 2008). The increase in fertility among cohabiting women on Fig. 2 may appear to be minimal relative to the decline in marital fertility, but the birth rates for cohabiting women nearly doubled between 1980–1983 and 1996–1999. Birth rates for single women fluctuated during the period, but also increased overall.

To determine the relative contribution of these rates to the percent of births by union status, we conduct two counterfactual analyses. In the first, we hold the rate of marital fertility constant at the 1980–1983 rate and let the single and cohabitation rates vary. In this scenario, nonmarital fertility increases from 15% to 25% throughout the 20-year period. The opposite counterfactual (holding constant the single and cohabitation rates) increases nonmarital fertility only from 15% to 19%, implying that increases in nonmarital fertility played a greater role than declines marital fertility. However, when we restrict the counterfactuals to 1996–1999, before the uptick in marital and single fertility, the contribution appears to be equal: nonmarital fertility increased from 15% to 18% for both scenarios. Thus, we estimate that the decline in marital fertility is responsible for one-third to one-half of the increase in the percentage of births out of wedlock.

The Association Between First-Birth Rates by Union Status and Education

As described earlier, SDT theory predicts that women with higher education should be the forerunners in childbearing within cohabitation, while the POD predicts that women with lower education are more likely to bear children out of wedlock. The descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 show that in general, childbearing to single and cohabiting women follows the POD. In every period, women with less than secondary education had the highest percentage of nonmarital births. There are no consistent differences between women with secondary and postsecondary education.

Table 1.

Distribution of first births by education, period, and union status: Women aged 15–49

| Period | Single (%) | Cohabiting (%) | Married (%) | N Births |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than secondary | ||||

| 1980–1983 | 23 | 15 | 62 | 47 |

| 1984–1987 | 24 | 22 | 54 | 46 |

| 1988–1991 | 19 | 17 | 64 | 69 |

| 1992–1995 | 18 | 22 | 60 | 50 |

| 1996–1999 | 28 | 15 | 58 | 40 |

| 2000–2003 | 22 | 22 | 56 | 41 |

| Secondary (including lower vocational) | ||||

| 1980–1983 | 9 | 6 | 85 | 391 |

| 1984–1987 | 7 | 10 | 83 | 340 |

| 1988–1991 | 11 | 10 | 78 | 353 |

| 1992–1995 | 10 | 11 | 79 | 253 |

| 1996–1999 | 7 | 17 | 76 | 225 |

| 2000–2003 | 14 | 17 | 68 | 202 |

| Postsecondary (specialized secondary and university) | ||||

| 1980–1983 | 9 | 7 | 84 | 135 |

| 1984–1987 | 9 | 11 | 80 | 137 |

| 1988–1991 | 13 | 12 | 75 | 113 |

| 1992–1995 | 14 | 11 | 75 | 106 |

| 1996–1999 | 17 | 17 | 66 | 64 |

| 2000–2003 | 16 | 14 | 70 | 132 |

Data are from the Russian GGS

The descriptive statistics, however, do not indicate whether differences between educational levels are statistically significant or changed over time. To address these issues, we incorporated education into our model. We tested for change over time in the effects of education on the logged hazards and found no evidence of such an interaction for this or any other model (results available upon request).

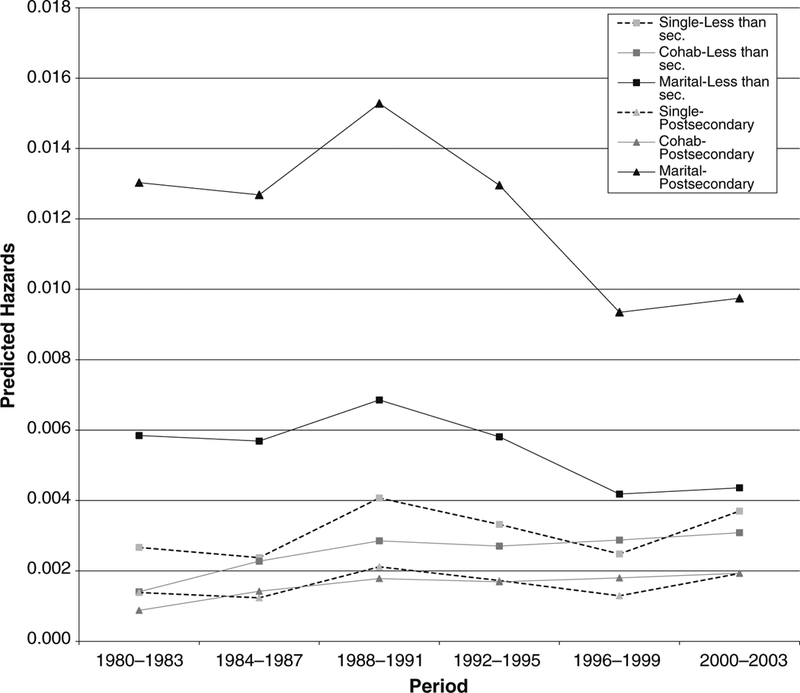

To illustrate the association between education and the raw rates of single, cohabiting, and marital births, we plot in Fig. 3 the predicted first-birth rates for the highest and lowest education levels implied by our preferred model (see Appendix Table 3 for parameter estimates).11 The evidence is more consistent with the POD perspective than with SDT: the rate of marital childbearing is significantly higher for women with postsecondary education than for women with less than secondary, while the least-educated women have the highest rates of both single and cohabiting births. The education gap in nonmarital childbearing stems mainly from the lower rates of marital births among those with less than secondary education. Although the least educated have consistently higher rates of cohabiting and single births than the most educated, the reverse gap in marital births is much greater in magnitude. Another result that casts doubt on the SDT perspective is that the rates of cohabiting and single births to more-educated women are about the same, while SDT predicts that cohabiting births should be more common. In contrast, the least-educated women generally have somewhat higher rates of single than cohabiting births, which is predicted by POD.12

Fig. 3.

Predicted first birth hazards by union status and level of education, adjusted for age (estimated at age 22): Women aged 15–49. Data are from the Russian GGS

Although the United States was once characterized by higher nonmarital childbearing rates among teenagers, our data show that teenage fertility is not very common in Russia. Births to 15- to 17-year-olds accounted for only 4.7% of first births and 8.7% of first births to single mothers in 1980–2003. In addition, teenage childbearing is not driving the education results presented in Fig. 3. Removing 15- to 17-year-olds from the analyses does not significantly alter the results in Fig. 3 (analysis not shown). Thus, nonmarital childbearing appears to be occurring among the least educated regardless of age constraints.

Conception Rates by Union Status

Models of fertility behavior within different union types demonstrate whether the trends in rates and their associations with education reflect the changing distributions across union statuses, fertility behavior, or both. We first estimate discrete-time models of the hazard of conception within each union status. These results cannot be compared directly because they are based on different risk sets. However, they provide a general idea of how the timing of fertility differs by education after (or whether) women have entered a union. To assess variation by education, we control for age, period, school enrollment, and duration in union (for the married and cohabiting women), which may be correlated with education and period and are likely to affect conception rates. Different specifications of these control variables and of education were optimal for each of the three risk sets (Table 2). Here, too, we found no significant interactions between education and period (data not shown). We also tested for change across periods in the effects of age and/or duration of relationship (for married and cohabiting respondents); only one—an interaction between period and duration for marital conceptions—was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Odds ratios from discrete-time hazard models of first-conception rates: Separate estimates for each union status, women aged 15–49

| Variable | Union Status at Conception | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Cohabiting | Married | |

| Less than secondary | 0.792* (−2.13) | ||

| Semiprofessional and university | 0.640** (−3.27) | 1.169 (1.91) | |

| Ref. = Secondary | |||

| 1980–1983 | 0.947 (−0.39) | 1.893*** (4.17) | 1.634*** (4.63) |

| 1984–1987 | 0.911 (−0.65) | 1.920*** (4.37) | 1.780*** (5.38) |

| 1988–1991 | 1.344* (2.13) | 1.744*** (3.76) | 1.864*** (5.67) |

| 1992–1995 | 1.201 (1.26) | 1.163 (0.99) | 1.196 (1.66) |

| Ref. = 1996–1999 | |||

| 2000−2003 | 0.915 (−0.57) | 0.818 (−1.40) | 1.053 (0.43) |

| School enrollment | 0.497*** (−6.83) | 0.604*** (−4.95) | 1.071 (0.99) |

| Age | 1.556*** (8.98) | 1.018 (0.59) | 0.863* (−2.35) |

| Age, squared | 0.967*** (−7.15) | 0.996*** (−3.46) | 1.011 (1.95) |

| Age, cubed | 1.001*** (4.51) | 0.999633** (−2.60) | |

| Duration in union | 0.965*** (−9.19) | 0.945*** (−11.94) | |

| Duration in union, squared | 1.000*** (6.20) | 1.000482*** (5.76) | |

| Duration in union, cubed | 0.999998*** (−4.11) | ||

| Duration in union × post-1991 | 1.010*** (4.57) | ||

| N (person-months) | 247,140 | 23,662 | 51,890 |

Numbers in parentheses are t statistics. Data are from the Russian GGS.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (one-tailed tests)

The effects of education on conception differ by union status. Among married women, those with less than secondary education had first conception rates that were 21% lower than those with secondary or vocational education. Postsecondary graduates had first conception rates that were 17% higher, although this term is not significant (it is, however, when the interaction term between duration and post-Soviet change is not included in the model). This result suggests that women with postsecondary education may have already been postponing marriage and thus may have quickly become pregnant after marriage. The opposite is true for the single women analyses; single women with semiprofessional or university education had conception rates that were 36% lower than single women with lower levels of education. Relative to women with a secondary education, it is rare for women with higher education to conceive out of union. Finally, education did not have any significant effects at all on conception rates for cohabiting women. This result does not explicitly support either the SDT or the POD perspective.

Changes in Union Status During Pregnancy

Table 2 also shows that the rates of conception declined within all three union statuses during the 1990s. The substantial decline in the rate of conceptions to cohabiting women and its lack of variation by education mean that the patterns in Figs. 2 and 3 must reflect some combination of changes in legitimation after conception (e.g., increasing cohabitation instead of marriage for pregnant single women) and changes in union formation prior to conception (e.g., increasing cohabitation, declining marriage rates). To test for changes in legitimation behavior, we estimate MLR models of union status at the time of birth for pregnancies initially conceived by single and cohabiting women.13 In these models, a single dummy variable denoting less than secondary education is the preferred specification, and once again, we found no significant interactions between education and period.

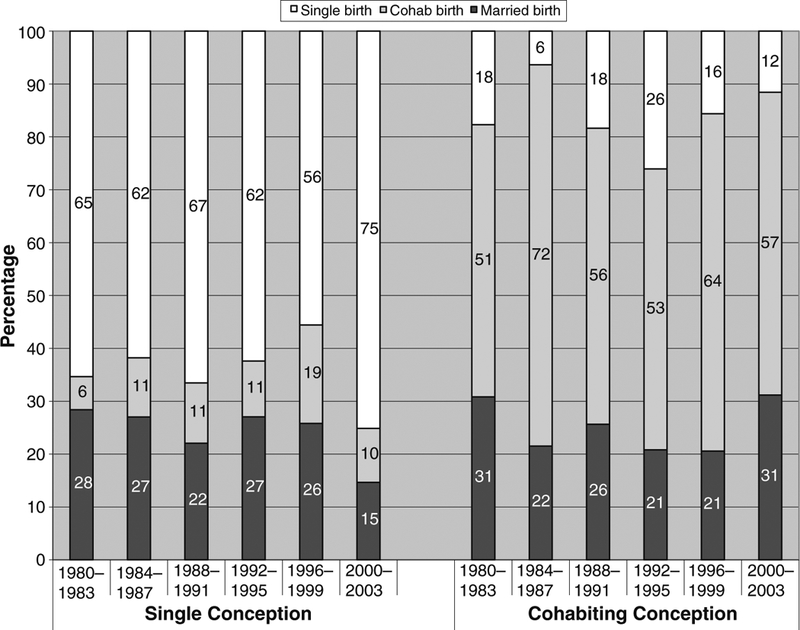

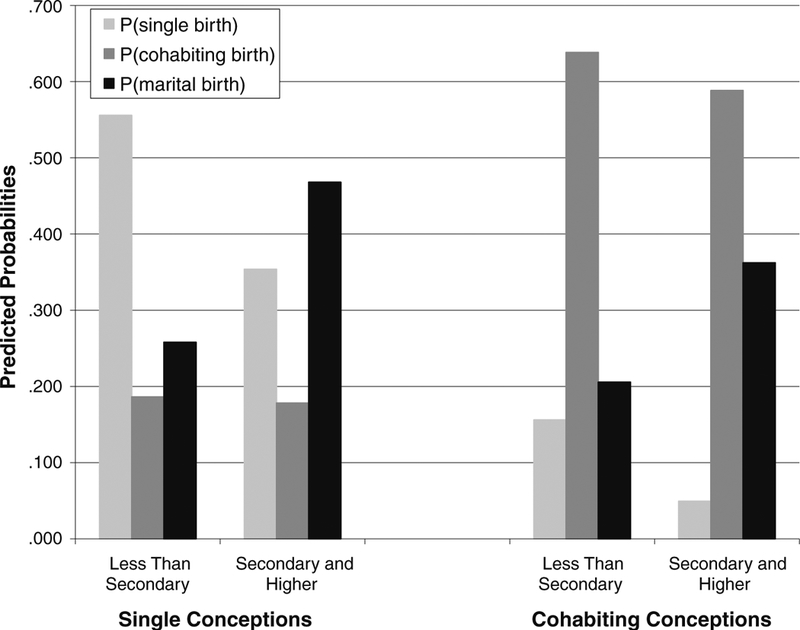

The implied predicted probabilities of each union status at the time of birth for each period (holding age at 22 and education at secondary or more) show no clear trend toward declining legitimation (Fig. 4, which is based on Appendix Table 4). The probability of marriage prior to birth for pregnant single women fluctuated around 50% until 2000–2003, when it declined sharply.14 Also, contrary to SDT, we see no evidence of a trend toward increasing cohabitation by women who conceived while single. Pregnant cohabiters show no changing tendency to remain within cohabitation: the predicted probability of doing so peaked in the mid-1980s and declined in 2000–2003. Consistent with POD, among women who conceive out of wedlock, those with the least education are significantly less likely to marry and more likely to be single at the time of birth, whether they were single or cohabiting initially (Fig. 5). Contrary to SDT, education has scant influence on the probability of cohabiting at time of birth for women who experience either form of nonmarital pregnancy.

Fig. 4.

Predicted percentage of single and cohabiting conceptions that result in each union status at birth (estimated at age 22, secondary degree): Women aged 15–49. Data are from the Russian GGS

Fig. 5.

Predicted probabilities of union status at first birth for women aged 15–49 single and cohabiting at conception, by education (estimated at age 22, 1996–1999). Data are from the Russian GGS

Our results thus far point to two trends that run opposite to explaining the “increase” in the percentage of births born to cohabiting mothers: (1) the rate of conceptions to cohabiting women declined from 1980 to 2003 at about the same pace as the rate of conceptions to married women; and (2) the rates of legitimizing cohabiting pregnancies and entering cohabitation after single pregnancies exhibited only moderate fluctuation. What then, can explain the pattern in Fig. 1 and the much discussed “increase” in nonmarital childbearing in Russia?

The answer is simple: the increase in the proportion of childless women of childbearing age living in cohabiting relationships was sufficient to offset the trends described earlier. Figure 6 shows that in 1982, only 4% of childless women aged 15–49 lived in cohabiting unions, but 20 years later, 16% of childless women lived in cohabiting unions. The percentage of childless women who were single remained fairly stable throughout the period. Without any changes in union status-specific rates of conception, the trends in Fig. 6 imply that the percentage of single and cohabiting births would increase. We do not analyze the trends and correlates of cohabitation in Russia here, however, because they have been studied extensively elsewhere (Gerber and Berman 2010; Hoem et al. 2009; Kostova 2007).

Fig. 6.

Distribution of childless women aged 15–49 by union status in December of each year. Data are from the Russian GGS

Discussion

Since the 1980s, nonmarital childbearing in Russia has increased dramatically, at least by the conventional measure of the percentage of births that occur out of wedlock. Most researchers studying this trend attribute it to the second demographic transition, brought on by the massive social change that occurred after the collapse of the Soviet Union (Hoem et al. 2009; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2002; Zakharov 2008). The usual assumption is that Russia is following the path of western European countries, particularly northern European countries, which started experiencing massive increases in the percentage of births to cohabitors in the 1970s. However, no studies on Russia (and few in western Europe, for that matter) have investigated the trends in the rates of single, cohabiting, and marital births that underlie the trends in the percentage of births that occur out of wedlock or the associations between these rates and education. Nor have any studies specifically examined conception rates within each union status or the probabilities of each union status at time of birth conditional on conception status. Our study provides an in-depth analysis into the trends and correlates of nonmarital childbearing and finds that the situation has more in common with the “pattern of disadvantage” characterizing nonmarital fertility in the United States than with the SDT pattern. However, the Russian case also exhibits some important features that neither pattern anticipates.

To arrive at these conclusions, we have focused on two types of evidence. The first examines how the trends and composition of nonmarital childbearing changed over time. The SDT predicts that there should be an overall increase in birth rates within cohabitation, while the POD emphasizes an increase in childbearing to single mothers, although increases in childbearing within unstable cohabiting unions—increasingly the case in the United States—could also be consistent with the POD (Raley 2001). Neither prediction is completely borne out in the Russian case. Although the rate of cohabiting first births doubled from 1980 to 2003 and indicates some change in childbearing behavior among cohabitors and single women, we estimate that between one-third and one-half of the percentage increase is due to the sharp decline in the rate of first marital births throughout the 1990s. Thus, neither the POD nor the SDT provides much help for understanding nonmarital childbearing in Russia, given the unprecedented decline to very low fertility.

The SDT predicts that fertility behavior within cohabiting unions should become more similar to that of married couples (Raley 2001), but we find that in Russia, conception rates within cohabitation have not increased over time, nor have they converged with those of married people. The SDT also predicts that single women will increasingly cohabit (rather than marry) following a pregnancy and that cohabiting women will be less likely to marry (Raley 2001). This has not happened in Russia; instead, there has been very little change in union formation during pregnancy for either single or cohabiting women, with the exception of 2000–2003, when single women became less likely to enter into cohabitation or marriage. The latter development might indicate a new trend, but it also could reflect random short-term fluctuation or sampling error; only time will tell. Overall, the lack of change in legitimation behavior seems very similar to the situation in the United States in the early 1990s, when increases in the proportion of births to cohabitors were driven by the increase in the proportion of the population that was cohabiting (Raley 2001).

We also examine the relationship between nonmarital childbearing and education. We argue that although the SDT has been conceptualized in many different ways (see Sobotka (2008) for a discussion), the underlying ideas usually associated with the SDT—for example, secularization, individualism, self-expression, and self-actualization—are intrinsically linked to higher education. Thus, it follows that highly educated women should be the forerunners of second demographic transition behaviors: namely, childbearing within cohabitation. The pattern of disadvantage, on the other hand, strongly predicts an association between lower education and childbearing within cohabitation or to single mothers; and in Russia, the least-educated women have the highest birth rates within cohabitation and as single mothers. Single women with the highest education have significantly lower first-conception rates than women with other educational levels, even with controls for school enrollment. After conception, the difference in educational level becomes most pronounced; the least-educated women who conceived while cohabiting are far more likely to remain within cohabitation or experience union dissolution, and the least-educated women who conceived while single are the least likely to enter any type of union. Thus, the majority of the education results are consistent with the POD. However, there is one important exception: we find no difference by level of education for conception rates within cohabitation, a result that cannot be explained by the POD or SDT. Further research is needed to elucidate the characteristics of Russian women who conceive within cohabitation.

Some limitations of this study must be noted. First, by focusing on first births, we do not address possible increases in nonmarital childbearing for higher parities, which could lead to slightly different interpretations from those presented earlier. Second, response rates in Moscow and St. Petersburg—by far, the largest urban areas in Russia—were very low, meaning that the survey can only be considered representative of the rest of Russia. The SDT could be advancing much more quickly in these cities, and highly educated women could be bearing children within cohabitation. We also do not have time-varying covariates for size of locality and cannot capture urban-rural effects that operate in tandem with education. In general, our models are relatively parsimonious and may not account for other factors that influence nonmarital childbearing, such as parental characteristics, housing availability, employment opportunities, and characteristics of the partner. Finally, because we cannot rule out unobserved factors that may be correlated with both education and nonmarital childbearing, we cannot claim to have demonstrated a causal relationship between the two. However, our goal is to adjudicate between two patterns of nonmarital childbearing (SDT and POD), goals that are met through descriptions of the association between education and birth by union status, as well as a focus on behaviors surrounding a nonmarital pregnancy.

To summarize, we find that the post-Soviet increase in the percentage of births out of wedlock resulted not so much from changes in the conception behavior of cohabitors, nor from changes in union formation behavior after conception, as from the increasing proportion of women who cohabit before conception. More women are now exposed to the risk of conceiving within cohabitation, but after they conceive, they are as just likely as before to marry. Thus, the increase in births within cohabitation is part and parcel of the “retreat” from marriage in Russia (Gerber and Berman 2010; Hoem et al. 2009). The relationship between education and nonmarital childbearing has not changed over time: the least-educated women have the highest birth rates as cohabiting or single mothers because of their rates of marriage prior to conception and their lower probabilities of legitimating a nonmarital conception. Thus, the least-educated women are at the greatest disadvantage when it comes to marriage after conception. We speculate that this is not because they are rejecting the institution of marriage in favor of autonomy, but rather because they or their partners are “unsuitable” for marriage, owing either to lack of employment opportunities or to other unfavorable characteristics (Edin and Kefalas 2005; Gibson-Davis et al. 2005). The collapse of the Soviet Union, which led to increases in economic instability, poverty, and anomie would have increased the number of women in this situation.

The pattern of disadvantage implies a divergence in family formation strategies based on socioeconomic status. Marriage remains an indicator of the greater opportunities and stability associated with higher education. This pattern seems to have been exacerbated by the economic turmoil during Russia’s transition to a market economy. Now, as inequality increases in Russia, family behaviors will most likely continue to diverge along two trajectories similar to those McLanahan (2004:608) described in the United States: “One trajectory—the one associated with delays in childbearing and increases in maternal employment—reflects gains in resources, while the other—the one associated with divorce and nonmarital childbearing—reflects losses.”

Taken as a whole, these results suggest that demographers should attend closely to differences between single and cohabiting women in their analyses; single women exhibit different behaviors from cohabiting women, and cohabiting women cannot simply be included with married women. In addition, research on nonmarital childbearing should incorporate more sophisticated techniques for studying the complicated process of nonmarital childbearing, a process that can involve changing union status at multiple points in the life course; our study provides one innovative approach, but there is room for development. Finally, further research needs to analyze the trends and correlates of cohabiting unions and nonmarital childbearing in Europe and other countries where the trend is increasing. Most studies that point to the diffusion of the second demographic transition rely on macro-level indicators for evidence, rather than conducting individual-level analyses to show that cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing are associated with certain values or ideas. Few European studies have analyzed the relationship between nonmarital childbearing and cohabitation and education, economic conditions, or values. In addition, it is important to note context-specific patterns that set initial conditions; for example, Hungary and Bulgaria have had a long history of cohabitation among disadvantaged groups (Carlson and Klinger 1987; Kostova 2007). Only studies that attend to these relationships can determine whether the second demographic transition is spreading or whether the family formation strategies of the highest and least educated are diverging.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a core grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development to the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (R24 HD047873) and the Max Planck Institute. The Russian Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) was conducted by the Independent Institute of Social Policy (Moscow) with the financial support of the Pension Fund of the Russian Federation and the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Germany. The design and standard survey instruments of the GGS were adjusted to the Russian context by the Independent Institute of Social Policy (Moscow) and the Demoscope Independent Research Center (Moscow) in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Rostock, Germany). We are grateful to Jan Hoem, anonymous reviewers, and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research for comments on earlier versions.

Appendix

Table 3.

Odds ratios of competing risk hazard model of union status at first birth with three outcomes: Single, cohabiting, and married women aged 15–49

| Variable | Union Status at Birth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Cohabiting | Married | |

| Less than secondary | 1.417 (1.89) | 0.910 (−0.50) | 0.399*** (−9.43) |

| Postsecondary | 0.741* (−2.02) | 0.572*** (−3.77) | 0.894 (−1.76) |

| 1980–1983 | 1.075 (0.35) | 0.490*** (−3.44) | 1.398*** (4.18) |

| 1984–1987 | 0.958 (−0.20) | 0.792 (−1.25) | 1.361*** (3.75) |

| 1988–1991 | 1.647* (2.46) | 0.996 (−0.02) | 1.646*** (6.05) |

| 1992–1995 | 1.341 (1.35) | 0.943 (−0.31) | 1.392*** (3.80) |

| Ref. = 1996–1999 | |||

| 2000–2003 | 1.492 (1.92) | 1.074 (0.39) | 1.044 (0.47) |

| School enrollment | 0.387*** (−6.22) | 0.302*** (−8.13) | 0.741*** (−5.20) |

| Age | 1.985*** (6.70) | 1.641*** (5.40) | 2.388*** (15.71) |

| Age, squared | 0.987*** (−6.97) | 0.990*** (−5.90) | 0.983*** (−16.34) |

| N (person-months) | 343,303 | ||

Numbers in parentheses are t statistics. Data are from the Russian GGS.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (one-tailed tests)

Table 4.

Multinomial logit model odds ratios for union status at birth for conceptions that occurred to single or cohabiting women

| Variable | Union Status at Conception | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Cohabiting | |||

| Single at Birth | Cohabiting at Birth | Single at Birth | Cohabiting at Birth | |

| Less than secondary | 2.849*** (4.06) | 1.896 (1.57) | 5.566*** (3.35) | 1.912* (2.38) |

| Ref = Secondary, postsecondary | ||||

| 1980–1983 | 1.069 (0.21) | 0.305* (−2.21) | 0.756 (−0.38) | 0.538 (−1.85) |

| 1984–1987 | 1.062 (0.18) | 0.574 (−110) | 0.390 (−1.03) | 1.080 (0.23) |

| 1988–1991 | 1.400 (1.07) | 0.715 (−0.74) | 0.943 (−0.09) | 0.703 (−110) |

| 1992–1995 | 1.071 (0.20) | 0.540 (−1.23) | 1.649 (0.75) | 0.822 (−0.59) |

| Ref: 1996–1999 | ||||

| 2000–2003 | 2.378* (2.49) | 0.964 (−0.07) | 0.489 (−0.99) | 0.592 (−1.68) |

| School enrollment | 0.532** (−3.08) | 0.439* (−2.45) | 0.331* (−2.36) | 0.441*** (−3.95) |

| Age | 1.148*** (4.98) | 0.979 (−0.40) | 1.120** (2.75) | 1.083*** (3.45) |

| N | 635 | 570 | ||

Numbers in parentheses are t statistics. The reference category for each model is married at birth, women aged 15–49. Data are from the Russian GGS.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (one-tailed tests)

Footnotes

Cohabitation began among the working-class population in Sweden and the least-educated in Norway, but it became widespread throughout the population in the 1970s (Hoem 1986; Perelli-Harris et al. 2009).

Women’s economic independence has been proposed as a reason for the decline in marriage and increase in cohabitation (Becker 1981). However, little empirical evidence supports this argument, at least in the United States (Goldstein and Kenney 2001; Oppenheimer 2003).

An increase in the rate of cohabitation should not, in and of itself, be viewed as an indicator of the SDT because cohabitation can play many different roles, including a stage in the marriage process (see Heuveline and Timberlake 2004).

For example, the proportion of single births in a given month is simply the rate of single births divided by the sum of the three respective birth rates in that month.

There are other ways to decompose nonmarital fertility rates (e.g., Raley 2001; Upchurch et al. 2002). For example, Smith et al. (1996) showed that the nonmarital fertility ratio is an exact function of the age distribution of childbearing-age women, the proportion of women at each age who are not married, and the age-specific birth rates of married and unmarried women. Our sample is far too small to support the estimation of age-specific rates, so we cannot incorporate age distribution as a dimension of decomposition. We do, however, include standard controls for the effects of age on fertility.

For more information on the GGS, see http://www.unece.org/pau/ggp/Welcome.html or http://www.socpol.ru/eng/research_projects/proj12.shtml, as well as Vikat et al. (2007).

The main disparities are that the GGS undersampled women aged 30–39 and oversampled women aged 40–54 at the time of the survey. It also slightly overestimated women in partnership, perhaps because they were more likely to be at home.

We imputed educational enrollment for women with missing graduation dates, based on average graduation dates from the entire sample.

Straightforward likelihood-ratio tests consistently supported the three-category specification of education yields over the five-category specification. We will supply the details of these tests upon request.

The best-fitting specification of the effect of age in this model was a second-order polynomial. For Fig. 2, we set age at 22 years old. Changing the value of age has only trivial impact on the patterns of change over time in the three rates we plot: it merely shifts the trend lines up or down, and bends the lines slightly without changing results.

Note that the variation by education in the rates fluctuates despite the lack of interaction terms between education and period. This reflects the nonlinear functional form of the MLR model: the annual changes in the baseline attributable to period effects inevitably produce modest changes in the “effects” of education on the raw hazards. However, concerns that the apparent changes in education are artifacts of our specification should be allayed by the fact that we tested for and ruled out interactions between education and period. Thus, the pattern in Fig. 3 provides the best fit to the data.

When interpreting these results in Fig. 3, bear in mind that the model controls for school enrollment and that the measurement of education, while crude, is time-varying. very few marital unions dissolved during pregnancy.

We do not analyze union status at time of birth for pregnancies conceived by married women because very few marital unions dissolved during pregnancy.

Only future studies based on more recent data will be able to determine whether the sudden drop in legitimation of first pregnancies for single female GGS respondents in 2000–2003 was a temporary phenomenon, random sampling error, or the start of a trend toward declining legitimation of single pregnancies. In the absence of a prior trend or a compelling reason to suspect legimitation to decline at precisely this point in time (when economic conditions were improving), we provisionally interpret it as a temporary fluctuation.

Contributor Information

Brienna Perelli-Harris, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Konrad-Zuse-Str. 1, 18057 Rostock, Germany perelli@demogr.mpg.de.

Theodore P. Gerber, Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA

References

- Anderson E (1990). Streetwise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brien MJ, Lillard LA, & Waite LJ (1999). Interrelated family-building behaviors: Cohabitation, marriage, and nonmarital conception. Demography, 36, 535–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines J, & Joyner K (1999). The ties that bind: Principles of cohesion in cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review, 64, 333–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, & Booth A (1996). Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 668–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, & Lu H-H (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E, & Klinger A (1987). Partners in life: Unmarried couples in Hungary. European Journal of Population, 3, 85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright K (2000). Shotgun weddings and the meaning of marriage in Russia: An event history analysis. The History of the Family, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, & Kefalas M (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber TP (2002). Structural change and post-socialist stratification: Labor market transitions in contemporary Russia. American Sociological Review, 67, 629–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber TP, & Berman D (2008). Heterogeneous condom use in Russia. Studies in Family Planning, 39, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber TP, & Berman D (2010). Entry to marriage and cohabitation in Russia, 1985–2000: Trends, correlates, and explanations. European Journal of Population, 26, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber TP, & Hout M (1998). More shock than therapy: Employment and income in Russia, 1991–1995. American Journal of Sociology, 104, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis C, Edin K, & McLanahan S (2005). High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1301–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, & Kenney CT (2001). Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review, 66, 506–19. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, & Timberlake JM (2004). The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1214–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoem J (1986). The impact of education on modern family-union initiation. European Journal of Population, 2, 113–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem JM, Kostova D, Jasilioniene A, & Muresan C (2009). Traces of the second demographic transition in central and eastern Europe: Union formation as a demographic manifestation. European Journal of Population, 25, 239–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle R, & Shkolnikov V (2005). Low response rates in the cities of Moscow and Sankt-Peterburg and GGS-census comparisons of basic distributions Working document provided with the GSS data file for Russia. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney CT, & McLanahan SS (2006). Why are cohabiting relationships more violent than marriages? Demography, 43, 127–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K (2004). Unmarried cohabitation and parenthood: Here to stay? European perspectives In Moynihan DP, Smeeding T, & Rainwater L (Eds.), The future of the family (pp. 66–95). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Klugman J, & Motivans A (Eds.). (2001). Single parents and child welfare in the New Russia. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kon IS (1995). The sexual revolution in Russia: From the age of the Czars to today Translated by J. Riordan New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kostova D (2007). The emergence of cohabitation in a transitional socio-economic context: Evidence from Bulgaria and Russia. Demografia, 50(5), 135–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe RJ, & Neidert L (2006). The second demographic transition in the United States: Exception or textbook example? Population and Development Review, 32, 669–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, & Surkyn J (2002). New forms of household formation in central and eastern Europe: Are they related to newly emerging value orientations? Interuniversity papers in demography. Brussels, Belgium: Interface Demography (SOCO), Vrije Universiteit Brussel. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter D, Roempke Graefe D, & Brown JB (2003). Is marriage a panacea? Union formation among economically disadvantaged unwed mothers. Social Problems, 50, 60–86. [Google Scholar]

- Maleva T, & Sinyavskaya O (2007). Roditeli i Deti, Myzhchini i Zhenschini v Semye i Obschestve [Parents and children, men and women in family and society], 1 Moscow: IISP. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD (1993). Marriage and cohabitation following premarital conception. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 839–50. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroz T, & Popkin BV (1995). Poverty and the economic transition in the Russian federation. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 22, 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Musick K (2007). Cohabitation, nonmarital childbearing and the marriage process. Demographic Research, 16, article 9:249–86. Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol16/9. [Google Scholar]

- Muszynska M (2008). Women’s employment and union dissolution in a changing socio-economic context in Russia. Demographic Research, 18, article 6:181–204. Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol18/6. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK (2003). Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career-development process. Demography, 40, 127–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B (2005). The path to lowest-low fertility in Ukraine. Population Studies, 59, 55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B (2006). The influence of informal work and subjective well-being on childbearing in post-Soviet Russia. Population and Development Review, 32, 729–53. [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B, Sigle-Rushton W, Lappegard T, Jasilioniene A, Di Giulio P, Keizer R, & Koeppen K (2009). Examining nonmarital childbearing in Europe: Does childbearing change the meaning of cohabitation? Presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Detroit, April 30–May 2. [Google Scholar]

- Philipov D, & Jasiloniene A (2008). Union formation and fertility in Bulgaria and Russia: A life table description of recent trends. Demographic Research, 19, article 62:2057–14. Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol19/62. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK (2001). Increasing fertility in cohabiting unions: Evidence for the second demographic transition? Demography, 38, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Morgan SP, & Offutt K (1996). Education and the changing age pattern of American fertility: 1963–1989. Demography, 33, 277–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel L (1989). La famille incertaine [The uncertain family]. Paris: Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Smith HL, Morgan SP, & Koropeckyj-Cox T (1996). A decomposition of trends in the nonmarital fertility ratios of blacks and whites in the United States, 1960–1992. Demography, 33, 141–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T 2008. “The diverse faces of the second demographic transition in Europe.” Demographic Research, 19, article 8:171–224. Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol19/8. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T, Zeman K, & Kantorová V (2003). Demographic shifts in the Czech Republic after 1989: A second demographic transition view. European Journal of Population, 19, 249–77. [Google Scholar]

- Steele F, Joshi H, Kallis C, & Goldstein H (2006). Changing compatibility of cohabitation and childbearing between young British women born in 1958 and 1970. Population Studies, 60, 137–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surkyn J, & Lesthaeghe R (2004). Value orientations and the second demographic transition (SDT) in northern, western, and southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research, Special Collection 3, article 3:45–86. Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/special/3/3. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Lillard LA, & Panis CWA (2002). Nonmarital childbearing: Influences of education, marriage, and fertility. Demography, 39, 311–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kaa D (2001). Postmodern fertility preferences: From changing value orientation to new behavior. Population and Development Review, 27(Suppl.), 290–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura S (2009). Changing patterns of nonmarital childbearing in the United States (NCHS Data Brief No. 18). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikat A, Spéder Z, Beets G, Billari FC, Bühler C, Désesquelles A, et al. (2007). Generations and gender survey (GGS): Towards a better understanding of relationships and processes in the life course. Demographic Research, 17, article 14):389–440. Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol17/14. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnevsky AG (1996). Family, fertility, and demographic dynamics in Russia: Analysis and forecast In Da Vanzo J (Ed.), Russia’s demographic “crisis” (pp. 1–35). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Center for Russia and Eurasia. [Google Scholar]

- Weakliem DL (2002). The effects of education on political opinions: An international study. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 13, 141–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, Bumpass LL, & Musick K (2001). Historical and life course trajectories of nonmarital childbearing In Wu LL & Wolfe B (Eds.), Out of wedlock: Causes and consequences of nonmarital fertility (pp. 3–48). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, & Wolfe B (Eds.). (2001). Out of wedlock: Causes and consequences of nonmarital fertility. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov SV (2008). The first and second demographic transition in Russia: Recent trends in the context of historic experience In Frejka T, Sobotka T, Hoem J, & Toulemon L (Eds.), Childbearing trends and policies: Country case studies (pp. 907–72). Rostock, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov SV, Vishnevskii AG, & Sakevich VI (2005). Brachnost i rozhdaemost [Marriage and fertility] In Vishnevskii AG (Ed.), Naselenie Rossii [Population of Russia] (pp. 40–130). Moscow: Higher School of Economics. [Google Scholar]