Abstract

Objective

The incidence and prevalence of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA) in the U.S. is not well characterized. Owing to its rarity, outcomes data in pediatric-onset GPA are also lacking. The aims of this study were to describe the epidemiology and outcomes of GPA patients in the U.S. and compare outcomes between pediatric and working-age adult patients.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study using the 2006 to 2014 Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Database was conducted. The incidence and prevalence rates of pediatric and adult (< 65 years) GPA patients were calculated. Outcomes among the two age groups were analyzed.

Results

5,566 cases of GPA were identified of which 214 (3.8%) were pediatric-onset and 5,352 (96.2%) were adult-onset. The incidence rate of pediatric-onset GPA was 1.8 cases/million person-years compared to 12.8 cases/million person-years in working-age adults. There was a slight female preponderance in both groups (63% and 54% in pediatric and adult GPA, respectively). Rates of hospitalization and severe infections were high in both children and working-age adults, but children had more frequent hospitalizations (RR 1.3 [95%CI 1.1-1.4]) and 2-3 times higher rates of leukopenia (RR 2.6 [95%CI 1.5-4.3]), neutropenia (RR 2.2 [95% CI 1.2-4.0]), and hypogammaglobulinemia (RR 3.7 [95%CI 2.0-6.4]). Time-to-event analyses showed no differences in the time to hospitalization, severe infection, major relapse or end-stage renal disease.

Conclusions

This study represents the largest cohort of GPA reported to date. Pediatric GPA patients experienced more frequent hospitalizations and were more vulnerable to hematologic complications than non-elderly adult patients.

Keywords: Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, GPA, epidemiology, outcome, administrative claims database

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, is a life-threatening vasculitis involving small to medium-sized blood vessels primarily in the respiratory tract and kidney. It is characterized by granulomatous inflammation, pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, and an association with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). The mortality rate associated with GPA is as high as 80% in untreated patients (1). However, use of intensive immunosuppressive regimens (eg. glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, methotrexate, azathioprine) has decreased mortality rates to nearly 10% (2, 3). Unfortunately, the morbidity associated with chronic disease and long-term immune suppression, including relapse, end-organ damage and persistent low-grade disease, too often results in a poor quality of life and a high economic burden (2, 4-6).

Published epidemiology studies of GPA have primarily focused on Europe, the United Kingdom, and Japan (7-15). Estimates of the overall incidence range between 0.5-20 cases/million with a prevalence of 20-160 cases/million (16, 17). A small population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota reported an incidence of 8 GPA cases/million but was limited by a small sample size (n= 8) (18). A larger U.S. study using a national hospital discharge database demonstrated a prevalence of 26 GPA cases/million based on 10,771 hospitalizations (19). The main limitation of this study was that it was unable to identify patients with milder disease who were not hospitalized (19).

Due to its rarity, much less is known about GPA in children. Studies of pediatric GPA have focused primarily on descriptions of presenting clinical characteristics in small cohorts, including a female preponderance and higher prevalence of ENT involvement when compared to adults (20). Two large registry studies have recently been published describing the presenting clinical features of 56 (21) and 183 (22) pediatric GPA patients. However, the epidemiology and clinical outcomes of pediatric GPA remain poorly characterized. There have been only 2 population-based studies published, and these were based on a very small number of pediatric GPA cases (n=15 (23) and 6 (24)). Longitudinal data from single or multiple centers in various countries have been limited to small cohorts of less than 30 cases. Aggregating the data from 8 previous reports of pediatric-onset GPA with longitudinal follow-up results in a total of 160 pediatric cases (with median follow up ranging between 3-19 years). Approximately 90% of these patients achieved remission, but 61% of them subsequently experienced a clinical relapse (20, 25-31). ESRD occurred in 12% of patients, while the overall mortality rate was low (5%) (20, 25-31). However, the data in these studies was incomplete and a better evaluation of outcomes in children is warranted.

Given the paucity of epidemiology and outcome data of GPA in both adults and children, we performed a study using a large insurance claims dataset from the years 2006-2014 to identify and characterize both pediatric and adult GPA patients (< 65 years) in the United States.

METHODS

Data source

Administrative claims data extracted from the Truven Health Analytic MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Database from January 1st 2006 to December 31st 2014 were analyzed. This database contains de-identified information of primarily employer-sponsored private health insurance claims from employees, their spouses, and their dependents aged less than 65 years from across the United States. The MarketScan database includes all medical claims (e.g. inpatient admissions, outpatient clinic visits, emergency department visits) and outpatient pharmacy claims with associated billing codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and National Drug Codes (NDC). Race, specific geographic data, inpatient medication usage, and laboratory study results are not included in the database. From 2006-2014, MarketScan included data from over 99 million individuals, of whom 25 million were children.

This study protocol underwent review by the Washington University Institutional Review Board and was determined to be exempt.

Patient selection

GPA cases were defined as patients with medical claims with a diagnostic code for GPA (ICD-9-CM code 446.4) in any claim field. To ensure that the GPA diagnosis was meaningful, the code for GPA was required to be present in ≥ 1 inpatient claim or ≥ 2 outpatient visit claims that were at least 30 days but not more than 12 months apart (32). The index date was defined as the date of first GPA coding. Patients aged between 2-64 years at the index date were included, and children were defined as those ≤ 18 years of age at the index diagnosis date. Patients were excluded if they had any of the following: 1) gap of enrollment ≥ 3 consecutive months, 2) claims for other vasculitic diseases (e.g., microscopic polyarteritis nodosa (446.0), Kawasaki disease (446.1), giant cell arteritis (446.5) and Takayasu arteritis (446.7)) after the GPA index date in ≥ 2 outpatient visits that were at least 30 days but not more than 12 months apart; or 3) presence of ICD-9-CM code for eosinophilia (228.3) in any claim field after the GPA index date (to exclude eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), which shares the same ICD-9-CM code with GPA).

Incidence and Prevalence

For the purpose of epidemiologic analyses and to determine time points for certain time-sensitive outcomes, we further characterized patients into incident (newly diagnosed) and prevalent (encompassing both newly diagnosed and pre-existing) cohorts. Given differences in the amount of time that each enrollee contributed to the dataset, we calculated incidence and prevalence as cases per million person-years. To minimize misclassifying pre-existing cases as incident cases, we required a minimum of 12 months of continuous enrollment prior to the index date of GPA coding to designate a case as incident. For this reason, we excluded all GPA cases from 2006 in the calculation of incidence (since they did not have the required 12-month observation period from the prior year). Because prevalence is a point estimate of disease, calculations for prevalence included all patients coded for GPA in our dataset.

Study variables and definitions

All patient demographic data were collected from the record at the time of the index GPA coding. Type of diagnostic setting (inpatient or outpatient) at the time of GPA diagnosis was collected only in incident cases. Complications and outcomes were analyzed from the entire GPA cohort with the exception of time-to-event analyses, which included only incident cases because time from initial diagnosis was required for the analysis. Outcomes of interest were identified using either ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes or standard algorithms for outpatient data (Supplemental Table 1). We defined ‘leukopenia’ as any code for decreased number of white blood cells, lymphocytes, or other white blood cells. We defined ‘chronic oxygen use’ as the presence of at least 2 claims (at least 30 days apart but within 12 months) for either respirator dependence or use of home oxygen equipment. We defined ‘severe infection’ as any inpatient hospitalization where the primary or a secondary diagnosis coded for an infection. Acute infections were then further categorized by organ system according to the classification of Hartman, et. al., (33). ‘Major relapses’ were defined by new pharmacy claims for either cyclophosphamide or rituximab associated with an outpatient visit or inpatient hospitalization containing the diagnostic code for GPA and a major relapse-associated condition based on components in BVAS (34). This definition was based on EULAR recommendations that major relapse of ANCA-associated vasculitis in clinical studies be defined as “re-occurrence or new onset of potentially organ- or life-threatening disease activity that cannot be treated with an increase of glucocorticoids alone and requires further escalation of treatment” (35). To ensure that we were identifying a major relapse in disease, the event had to be greater than 30 days after the initial diagnosis as well as greater than 30 days after prior pharmacy claims for either cyclophosphamide or rituximab (adapted from (4) and (35)). End-stage renal disease (ESRD) was defined as coding for any of the following: ESRD, chronic kidney disease stage 5, kidney transplant, or at least 2 claims for dialysis or dialysis-related procedures at least 30 days but no longer than 12 months apart. Death was captured from inpatient files and represented all-cause mortality.

For all time-to-event analyses and presence of certain complications (ESRD, chronic oxygen use, malignancy, subglottic stenosis, leukopenia, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia), only the first occurrence was counted. All occurrences of hospitalization, major relapse, and severe infection were counted from index date of GPA coding until the end of data availability, end of enrollment, or death. To avoid falsely identifying certain outcomes during the initial presentation, all time-to-event analyses included only those events occurring at least 30 days after the date of initial diagnosis. Results were presented both as frequency (%) and rate of occurrence (events/1,000 person-years of observation (PYO)).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the incidence and prevalence of GPA per million person-years in both pediatric and working-age adult cohorts. Because of previously published differences in the rates of certain complications of GPA between adults and children in smaller cohort studies, we chose to separately identify and analyze pediatric and working-age adult cohorts. We selected the age cutoff of 18 years because of both biologic development as well as the potential for differences in both practice and coding in adult versus pediatric health care settings. To assess the robustness of any findings between our pediatric and working-age adult groups, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing clinical outcomes with additional ‘young’ (aged 12-21 years) and ‘older’ (aged 50-60 years) cohorts.

Categorical variables were expressed as value and percentage, and statistical significance was determined using the chi-square test. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used to express non-normally distributed, continuous data and were compared by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Events were presented as rates (events/1,000 person-years) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated using the standard formula for rates (Poisson CI). Repeated events were compared using a negative binomial regression. Time-to-event data were compared using a univariate Cox proportional hazards model. We considered results to reach statistical significance when p≤0.05. We conducted all statistical analyses using STATA (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

Incident Cohort

Among nearly 237,542,000 person-years of observation between 2007-2014, we identified 1,969 incident GPA cases. Of these incident cases, 94 (4.8%) were children and 1,875 (95.2%) were adults <65 years old. The median age at GPA diagnosis was 15 years (IQR 13-17) and 53 years (IQR 44-59) in children and working-age adults, respectively (Table 1). The majority of pediatric patients (79.8%) were 12-18 years of age at diagnosis, and only 19 patients (20.2%) were diagnosed before the age of 12. The largest percentage of working-age adult patients with incident GPA were 50-59 years old (38.5%). There was a slight female preponderance in both groups (53.2% in children and 54.1% in adults; Table 1). The majority (58.5%) of pediatric patients were first coded with GPA during a hospitalization, while only 38.0% of working-age adults were first coded for GPA as an inpatient (p < 0.001). The median length of hospital stay for persons hospitalized at the time of diagnosis was 9.5 days (IQR 5-14) in children and 7 days (IQR 4-12) in adults (p=0.08). The estimated incidence rate of GPA was 1.8 cases per 1,000,000 person-years in children and 12.8 cases per 1,000,000 person-years in working-age adults (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the GPA patients in the MarketScan database *

| Incident cases (n=1,969) | All cases (n= 5,562) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Children (n = 94) |

Adults (n = 1,875) |

Children (n = 214) |

Adults (n = 5,348) |

|

| Age, yearsa | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.1 (3.1) | 49.9 (11.2) | 14.6 (3.0) | 48.5 (11.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (13-17) | 53 (44-59) | 15 (13-17) | 51 (41-58) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 2-11 | 19 (20.2) | – | 35 (16.4) | – |

| 12-18 | 75 (79.8) | – | 179 (83.6) | – |

| 19-29 | – | 148 (7.9) | – | 510 (9.5) |

| 30-39 | – | 186 (9.9) | – | 710 (13.3) |

| 40-49 | – | 404 (21.6) | – | 1,147 (21.5) |

| 50-59 | – | 722 (38.5) | – | 1,957 (36.6) |

| 60-64 | 415 (22.1) | 1,024 (19.2) | ||

| Female, n (%) | 50 (53.2) | 1,015 (54.1) | 135 (63.1) | 2,849 (53.3) |

| F: M | 1.1:1 | 1.2:1 | 1.7:1 | 1.1:1 |

| Enrollment period, median (IQR) years | 5.7 (3.9-8.0) | 5.0 (3.2-7.0) | 3.0 (1.7-6.0) | 2.8 (1.5-5.0) |

| Follow up timeb, median (IQR) years | 2.2 (0.8-3.9) | 1.6 (0.7-2.9) | 1.9 (0.9-3.4) | 1.6 (0.8-3.0) |

| Diagnostic setting, n (%) | ||||

| Outpatient | 39 (41.5) | 1,162 (62.0) | – | – |

| Inpatient | 55 (58.5) | 713 (38.0) | – | – |

SD = Standard deviation; IQR = Interquartile range.

The age represents the age at the time of first coding.

Time from first coding of GPA until the end of data availability.

Table 2.

Incidence rate (2007-2014) and prevalence rate (2006-2014) of GPA in the United States

| Children | Adults | Children and adults | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate | |||

| Number of cases | 94 | 1,875 | 1,969 |

| Denominator (person-years) | 52,830,433 | 146,462,727 | 199,293,161 |

| Cases/million person-years (95%CI)* | 1.8 (1.4-2.2) | 12.8 (12.2-13.4) | 9.9 (9.5-10.3) |

| Prevalence rate | |||

| Number of cases | 214 | 5,348 | 5,562 |

| Denominator (person-years) | 62,419,872 | 175,122,086 | 237,541,959 |

| Cases/million person-years (95%CI) | 3.4 (3.0-3.9) | 30.5 (29.7-31.3) | 23.4 (22.8-24.1) |

95%CI = 95% confidence interval

Prevalent Cohort

A total of 5,562 GPA cases from approximately 99,260,000 enrollees aged 2-64 years were identified, of which 214 (3.8%) were children and 5,348 (96.2%) were working-age adults. The majority of pediatric patients (83.6%) were between the ages of 12-18 years (Table 1). Over half of the adult patients (55.8%) were 50-64 years of age (Table 1). Patients in both age groups demonstrated a female predominance (63.1% in children and 53.3% in adults) although the female to male ratio was significantly higher in the pediatric group (1.7:1, p =0.009) (Table 1). The prevalence of GPA was 3.4 cases per million person-years in children and 30.5 cases per million person-years in adults less than 65 years of age (Table 2).

Complications and clinical outcomes

Serious events

A total of 307 hospitalizations (unrelated to initial diagnosis) occurred in 113 of the 214 pediatric patients after the diagnosis of GPA (range 1-14 admissions per child), which equated to a rate of 580 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years. In working-age adults, the rate was lower with 5,522 hospitalizations in 2,406 of the 5,348 adults with GPA (range 1-29 admissions per person), corresponding to a rate of 463 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years (Table 3). While the rate of hospitalizations in pediatric patients was 1.3 times higher compared to adults (95%CI 1.1-1.4), the median hospital length of stay of children for these admissions was shorter than for adults (4 days, IQR 3-8 days vs. 5 days, IQR 3-8 days, p =0.018).

Table 3.

Complications and clinical outcomes of GPA patients

| Pediatric GPA (n = 214) |

Adult GPA (n = 5,348) |

Rate ratioa (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases or events Rate per 1,000 PYO (95% CI) |

Cases or events Rate per 1,000 PYO (95% CI) |

||

| Serious events | |||

| All hospitalizations | 307 580 (517-649) |

5,522 463 (451-476) |

1.3 (1.1-1.4) |

| All severe infections | 89 168 (135-207) |

2,033 170 (163-178) |

1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

| All major relapses | 18 34 (20-54) |

671 56 (52-61) |

0.6 (0.4-1.0) |

| ESRD | 35 66 (48-92) |

742 62 (58-67) |

1.1 (0.8-1.5) |

| Death | 5 10 (3-22) |

154 13 (11-15) |

0.7 (0.2-1.7) |

| Other events | |||

| Chronic oxygen use | 4 8 (2-19) |

346 29 (26-32) |

0.3 (0.1-0.7) |

| Malignancy | 4 8 (2-19) |

467 39 (36-43) |

0.2 (0.1-0.5) |

| Subglottic stenosis | 18 | 230 | |

| 37 (22-58) | 19 (17-22) | 1.8 (1.0-2.9) | |

| Leukopenia | 17 33 (20-53) |

146 12 (10-14) |

2.6 (1.5-4.3) |

| Neutropenia | 13 25 (14-43) |

136 11 (10-14) |

2.2 (1.2-4.0) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 15 29 (17-48) |

95 8 (6-10) |

3.7 (2.0-6.4) |

95%CI = 95% confidence interval; PYO = person-years of observation.

Rate ratio compares rate of outcomes of children to adults.

A total of 89 severe infections occurred in 51 (23.8%) pediatric patients (range 1-6 severe infections) compared to 2,033 severe infections in 1,015 (19.0%) working-age adults (range 1-20 severe infections). There was no difference in the rate of overall severe infection between children and adults (rate ratio 1.0, 95% CI 0.8-1.2). Among subcategories of infection, the rate of pulmonary infection were the higest in both groups (approximately 50 infections per 1,000 person-years in both groups) followed by intraabdominal, soft tissue/skin, septicemia, genitourinatry tract, and CNS infection (data not shown).

A total of 18 major relapses were identified in 11 (5.1%) pediatric patients, which was similar to the 671 major relapses observed in 291 (5.4%) working-age adults with GPA (Table 3). The average number of major relapses per patient were 1.6 (SD ± 0.9) in children and 2.3 (SD ± 2.2) in adults. Children demonstrated a lower rate of major relapse compared to adults (RR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4-1.0), but this was not statistically significant.

The overall rate of ESRD appeared higher in pediatric patients compared to adults <65 years of age (RR 1.1, 95%CI 0.8-1.5) but this was not statistically significant (Table 3). Among incident cases who progressed to ESRD (17 children and 319 adults), most patients (94.1% of children and 76.8% of adults) were diagnosed with ESRD within 3 months of their GPA diagnosis. All of the children and the overwhelming majority of adults (89.9%) in the incident cohort who developed ESRD did so within 1 year of GPA diagnosis.

All-cause mortality rates in children and working-age adults were comparable (RR 0.7, 95% CI 0.2-1.7) (Table 3). Among the 70 working-age adult incident cases of GPA who died, 36 (51.4%) died within 6 months of their GPA diagnosis, and 50 (71.4%) died within 1 year of diagnosis. Very few children with GPA died during the period of observation (n = 5).

Other events

Children had higher rates of hematologic complications than working-age adults, including leukopenia (RR 2.6, 95% CI 1.5-4.3), neutropenia (RR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2-4.0) and hypogammaglobulinemia (RR 3.7, 95%CI 2.0-6.4) (Table 3). In contrast, children with GPA had a lower rate of chronic oxygen use compared to working-age adults (RR 0.3, 95%CI 0.1-0.7) (Table 3). Rates of malignancy were also significantly lower in children with GPA than in adults (RR 0.2, 95%CI 0.1-0.5). Of the 170 adult incident cases that developed cancer, 100 (58.8%) were coded for malignancy within 6 months of the GPA diagnosis, consistent with malignancy preceding or occurring concurrently with the diagnosis of GPA. Finally, although there was a trend towards a higher rate of subglottic stenosis in children, the rate ratio between pediatric and working-age adult GPA patients did not reach statistical significance (RR 1.8, 95% CI 1.0-2.9).

Sensitivity analysis of serious events in the young vs older cohorts

Our sensitivity analysis consisted of a ‘young’ cohort of 292 patients aged 12-21 years and an ‘older’ cohort of 2,191 patients aged 50-60 years. As expected, rates of serious events in the ‘young’ cohort were similar to those in the original pediatric GPA cohort, with the exception of the rate of cytopenias (which were slightly lower) and the rate of severe infections, which ocurred at nearly half the rate of the original pediatric cohort (Table 4). The rate of severe infection in the ‘older’ cohort was also nearly half the rate of the original 19-64 year old adult cohort, while the rates of chronic oxygen use and malignancy were slightly higher (Table 4). Overall, the rate ratios for serious events between groups in the sensitivity analysis were not significant, with the exception of subglottic stenosis (RR 3.2, 95% CI 1.9-5.1) which appears significantly more common in pediatric and young adults compared to the “older” cohort (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of complications and clinical outcomes of GPA patients among children aged 12-21 years and adults aged 50-60 years *

| Pediatric GPA (n = 292) |

Adult GPA (n = 2,191) |

Rate ratioa (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases or events Rate per 1,000 PYO (95% CI) |

Cases or events Rate per 1,000 PYO (95% CI) |

||

| Serious events | |||

| All hospitalizations | 383 530 (478-585) |

2,509 473 (454-491) |

1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

| All severe infections | 65 90 (76-104) |

468 88 (83-92) |

1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

| All major relapses | 24 33 (21 – 49) |

293 55 (49-63) |

0.6 (0.4-0.9) |

| ESRD | 44 71 (52-96) |

332 70 (63-79) |

1.0 (0.7-1.4) |

| Death | 4 6 (2-14) |

75 14 (11-18) |

0.4 (0.1-1.0) |

| Other events | |||

| Chronic oxygen use | 2 3 (1-38) |

190 38 (33-44) |

0.1 (0.01-0.3) |

| Malignancy | 3 4 (0-12) |

277 58 (51 -65) |

0.1 (0.02-0.2) |

| Subglottic stenosis | 25 | 62 | |

| 38 (25-56) | 12 (9-15) | 3.2 (1.9-5.1) | |

| Leukopenia | 15 21 (12-35) |

70 13 (10-17) |

1.6 (0.9-2.8) |

| Neutropenia | 11 18 (8-28) |

65 13 (10-16) |

1.3 (0.6-2.4) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 11 16 (8-28) |

46 3 (2-5) |

1.8 (0.8-3.5) |

95%CI = 95% confidence interval: PYO = person-years of observation.

Rate ratio compares rate of outcomes of children to adults.

Time to serious events in the incident pediatric and adult populations

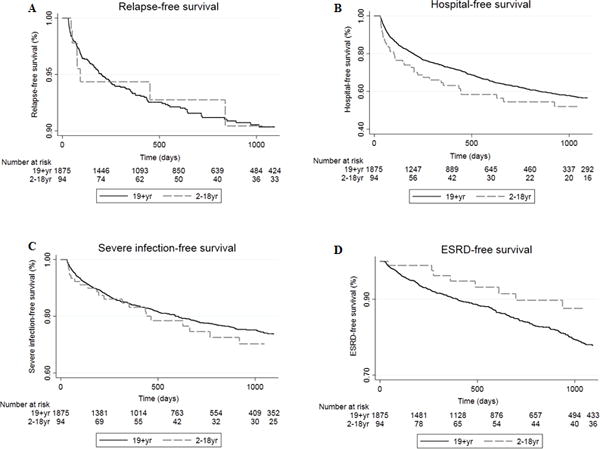

Overall, the mean time to the first serious event for incident GPA cases was 7 months for pediatric patients and 9 months for adults <65 years of age. Time to the development of ESRD was the shortest interval to a serious event in both age groups (mean of 1 month in children and 4 months in adults) (Figure 1). The time to hospitalization for severe infection had the longest interval in both age groups (mean of 1.1 years in both children and adults). There was no difference in the time from GPA diagnosis to first hospitalization, severe infection, major relapse or ESRD between pediatric and adult patients (Figure 1, all p > 0.05).

Figure 1. Comparison of Survival Curves for Several Clinical Outcomes in Children and Adult Patients in the Incident GPA Cohort.

Event-free survival of A) relapse, B) hospitalization, C) severe infection, and D) end stage renal disease (ESRD) of children (n=94) and adults (n=1,875) in the incident GPA cohort. Univariate Cox proportional hazards testing showed no significant differences between age groups for any of the four outcomes.

Discussion

This study of 5,562 cases of GPA is the largest cohort that has been reported in the medical literature to date and provides insight into the incidence, prevalence, and outcomes for GPA patients in the United States. This study also delineates similarities and differences in the course of GPA between pediatric and working-age adult GPA patients. We found that the incidence and prevalence of GPA were 7-fold and 9-fold lower, respectively, in children than in working-age adults, and that children are more likely to be hospitalized at diagnosis than adults <65 years old. Hospitalizations and severe infections were the most common complications in both age groups, but children had rates of hospitalization 1.3 times that of adults <65 years old. Although many event rate outcomes were comparable, children had significantly higher rates of hematologic complications than their adult counterparts.

A number of previous epidemiologic studies have been reported in adult GPA, primarily from Europe (7-9), United Kingdom (10, 13), Japan (11, 14) and Australia/New Zealand (12, 15). Our study found an incidence rate of 12.8 per million person-years in the U.S. which is comparable with a prior smaller UK report which found an incidence rate of 14.0 per millon person-years (24). We found a prevalence rate of 30.5 per million person-years in the U.S. over a 9 year period, but it is difficult to directly compare to prior studies that commonly use point prevalence of a specific year (16, 36). A rough estimation of period prevalence (defined as cases per million persons) from our study would be 74 per million adult persons aged 19-64 years, with the caveat that this is likely an underestimation of prevalence given that people with short enrollment times were included in the denominator. One large previous study that analyzed data from the U.S. National Hospital Discharge Survey estimated a period prevalence of 26 per million persons based on 10,771 hospital discharges from 1986-1990 (19). Our higher prevalence could be explained by longer study duration (9 vs 5 years) or potentially by an increase in GPA incidence over the last 20 years. However, it could also be a result of an underestimate of the true incidence in the prior study due to its reliance on hospitalized patients; in our study, only 38% of adult GPA patients (714 of 1,875 incident GPA patients) were hospitalized at the time of diagnosis, and 45% were hospitalized at least once after diagnosis over the 9 year study period.

To our knowledge, our study represents the first large epidemiologic study of pediatric GPA, encompassing 214 pediatric GPA patients. We found an incidence rate of 1.8 per million person-years among children. Two small studies have previously reported incidence rates of 2.8 cases/million persons/year (based on 15 cases of pediatric GPA at a single tertiary center in Southern Alberta, Canada from 1993-2008 (23)) and 0.9 per million person-years during 1997-2013 (based on 6 pediatric GPA patients in a UK study (24)). Despite the very small number of pediatric patients in these prior studies and the use of different study designs and the age range representing children, our estimate of annual incidence rate is quite similar to these prior estimates. The estimated prevalence of pediatric GPA in our study was 3.4 per million person-years, substantiately lower than prevalence of 30.5 per million person-years observed in our study for working-age adult GPA.

Our study demonstrated a slight female predominance in both pediatric and adult GPA cohorts, confirming the female predominance of pediatric GPA which has been observed in nearly all previous studies (20-22, 27-29, 37) and some prior studies focused on adult GPA (6, 19, 38). In contrast, higher male proportions (M:F ratio 1.2-1.6:1) or equal gender distributions have been reported in a number of other large adult population-based studies (7-10, 39, 40). The relatively small magnitude and equivocal nature of sex distributions in adult GPA studies suggests that sex may not be a significant contributor to the pathophysiology of this disease.

Some differences have been previously described in disease presentation and outcome between adult and pediatric patients, but distinctions in disease severity, response to therapy, and disease outcomes have not been widely investigated. In an older study conducted at the NIH in the 1990s (with 23 pediatric and 158 adult onset GPA patients), clinical phenotypes were similar with the exception that subglottic stenosis was five times more common in children (48% vs 10%) and there was a slightly lower frequency of ESRD in pediatric patients (9% vs 13%) (20). Surprisingly, we found no significant difference in the rate of subglottic stenosis between pediatric and working-age adult GPA patients in our much larger cohort, although our sensitivity analysis showed 3-fold higher rates of subglottic stenosis in younger persons compared to adults aged 50-60 years. Although we suspected that ESRD would take many years to develop and therefore would be found infrequently in children, we found similar rates of ESRD among pediatric and working-age adult GPA patients, and that the majority of patients progressed to ESRD in the first year of their disease. The ARChiVe registry very recently published 12 month outcomes for 105 pediatric patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) of which 85 patients had GPA (although the data were aggregated and not separated from the other AAV patients)(37). This study found that 11.4% of the 105 pediatric AAV patients had ESRD at 1 year which is comparable to the 16.4% of pediatric GPA patients with ESRD in our cohort.

Rates of hospitalization and severe infections have been reported to be high in prior studies of adult GPA (41, 42). For example, a study of GPA patients in an all-payer U.S. inpatient database (National Inpatient Sample) reported that infections (particularly respiratory tract infections) were the most frequent reason for hospitalization (25%) and also a primary contributor to death (16.4% of all in-hospital mortality cases)(41). In our study, pediatric and working-age adult GPA cohorts had comparable high rates of severe infections, whereas the hospitalization rate was higher in pediatric GPA patients. We hypothesize that this disparity may reflect a lower threshold for hospital admission in children, but it is unclear whether they had higher disease severity leading to admission. Our analysis, which included data from both inpatient and outpatient environments, found that respiratory tract infections were the most common type of infection in both groups, consistent with previous studies (41, 42).

The mortality rates in both the working-age adult and pediatric GPA populations were the highest in the first year following diagnosis (accounting for over 70% of deaths), consistent with prior observations (42-44). Overall, rates of mortality and major relapse events were relatively low in our study cohort, which may be related to the ‘healthy worker effect’ of this dataset, wherein insured adults only remain in the dataset if they are working, dependents, or enrolled in Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act continuation of insurance after ending employment. Patients with severe disease who are no longer employable, or caregivers who leave or change employment to provide care for a severely debilitated dependent would drop out of this dataset, potentially lowering the overall event rate in this population. Our complication and mortality rates will also be affected by the overall “young” age of our GPA population (< 65 years old), since data for elderly persons was not available. Elderly patients have worse outcomes compared to younger GPA patients (3, 42), and increased age and renal impairment have previously been identified as major risk factors for poor outcomes and mortality in GPA (3, 42, 45-48). Indeed a multivariable analysis of a population-based group of 56 GPA patients estimated an increase in 10 years of age increased the risk of mortality (HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.38-3.42, p <0.001) and ESRD (HR 1.47, 95% CI 0.95-2.24, p=0.08) in GPA (46).

Interestingly, we found that pediatric GPA patients had 2-3 times higher rates of leukopenia, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia compared to the working-age adult cohort. It is possible that these complications are less commonly coded for adult patients, because other more significant health concerns exist and have more impact on reimbursement than these laboratory findings. In administrative datasets, such practices are all but impossible to confirm. Furthermore, due to the age cut-off of 64 years in our study, our adult calculations will underestimate the complications that occur with greater frequency in elderly adults with GPA (e.g., anemia, infections, and renal involvement)(3, 42, 45-49).

The primary strengths of this study are its size, inclusion of data from all regions of the United States for nine years, and the comparison of pediatric and working-age adult GPA patients from the same population. The data were obtained from medical claims from both inpatient and outpatient settings, allowing a comprehensive capture of the full continuum of care. Moreover, the results represent the outcomes in a variety of health care environments and insurance plan coverage, thereby minimizing potential confounders in practice variation that complicate studies from single or regional centers.

There are some potential limitations of our study. First, the inability to link the claims data to direct clinical information precluded the verification of the GPA diagnosis (e.g., ensuring that patients fulfilled ACR/ EULAR/PRINTO/PRES classification criteria). Second, patients with EGPA might have been misclassified as GPA given its shared ICD-9-CM code. However, we hoped to minimize this misclassification by excluding patients with eosinophilia (an approach which has been previously reported to have a positive predictive value of 92.4%)(50). Third, we did not include glucocorticoid treatment itself as an indicator for major relapse (based on the EULAR standardized definition of major flare in ANCA-associated vasculitis in clinical studies (35)). In addition, there is wide clinical variability in steroid prescribing patterns and difficulties in using outpatient pharmacy data taking into account glucocorticoid strength and days’ supply. Therefore, our algorithm for identifying major relapses (defined in the Method’s section) may miss minor relapses that were treated solely with glucocorticoids. Fourth, coding for certain outcomes that are traditionally identified through clinical testing (such as leukopenia or hypogammaglobulinemia) is highly variable in administrative datasets, and therefore our results likely represent underestimates of the true prevalence of these complications. Fifth, the median time from first GPA coding until the end of data availability was approximately 2 years in both pediatric and adult patients. This duration might be insufficient to capture the longer-term or cumulative effects of some outcomes such as malignancy, ESRD, or mortality. Certainly, duration of observation has a significant effect on the frequency of rare, late complications of disease. While this is generally one of the strengths of large administrative datasets, we acknowledge that this limitation can even be present in very large datasets, such as the Truven Commercial Claims and Encounters. Also, our data is limited to privately insured patients, and the results may not be representative of patients with other types of insurance or without health insurance coverage. Finally, we acknowledge that due to the variable duration of enrollment in the dataset, we were obliged to calculate incidence and prevalence in units of person-years of observation. This differs from many other studies, and limits our ability to directly compare rates found in our population to that found by other investigators.

In summary, this large cohort of pediatric and working-age adult GPA patients provides novel information on incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of GPA in the United States. Severe infections and hospitalizations were the most common adverse complications for children and adults with GPA. Pediatric patients experienced higher rates of hematologic complications and hospitalizations than their adult counterparts, whereas the rates of ESRD, relapse, and severe infection were comparable. Longer-term studies with large cohorts are still needed to better characterize the rare and long-term complications of GPA. Future work will investigate the role of different treatment strategies on these outcomes to better improve the quality of care of these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kevin Baszis (Department of Pediatrics, Washington University), Seth Eisen (Department of Medicine, Washington University), and Prabha Ranganathan (Department of Medicine, Washington University) for helpful, broad conversations regarding the analysis approach and interpretation of the data.

Funding source: The Center for Administrative Data Research is supported in part by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant Number R24 HS19455 through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and Grant Number KM1CA156708 through the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations

- GPA

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- AAV

anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions:

All authors were involved in drafting and revising the article and approve the final version submitted for publication. Dr. Hartman had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Panupattanapong, Hartman, French, Olsen

Acquisition of data. Panupattanapong, Stwalley, Hartman, Olsen

Analysis and interpretation of data. Panupattanapong, Stwalley, Hartman, French, White

References

- 1.Walton EW. Giant-cell granuloma of the respiratory tract (Wegener’s granulomatosis) Br Med J. 1958;2(5091):265–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5091.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, Hallahan CW, Lebovics RS, Travis WD, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(6):488–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukhtyar C, Flossmann O, Hellmich B, Bacon P, Cid M, Cohen-Tervaert JW, et al. Outcomes from studies of antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody associated vasculitis: a systematic review by the European League Against Rheumatism systemic vasculitis task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(7):1004–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raimundo K, Farr AM, Kim G, Duna G. Clinical and Economic Burden of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-associated Vasculitis in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(12):2383–91. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman GS, Drucker Y, Cotch MF, Locker GA, Easley K, Kwoh K. Wegener’s granulomatosis: patient-reported effects of disease on health, function, and income. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(12):2257–62. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2257::AID-ART22>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdou NI, Kullman GJ, Hoffman GS, Sharp GC, Specks U, McDonald T, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis: survey of 701 patients in North America. Changes in outcome in the 1990s. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(2):309–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight A, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Askling J. Increasing incidence of Wegener’s granulomatosis in Sweden, 1975-2001. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(10):2060–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takala JH, Kautiainen H, Malmberg H, Leirisalo-Repo M. Incidence of Wegener’s granulomatosis in Finland 1981-2000. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(3 Suppl 49):S81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terrier B, Dechartres A, Deligny C, Godmer P, Charles P, Hayem G, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis according to geographic origin and ethnicity: clinical-biological presentation and outcome in a French population. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(3):445–50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts RA, Al-Taiar A, Scott DG, Macgregor AJ. Prevalence and incidence of Wegener’s granulomatosis in the UK general practice research database. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(10):1412–6. doi: 10.1002/art.24544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto S, Watts RA, Kobayashi S, Suzuki K, Jayne DR, Scott DG, et al. Comparison of the epidemiology of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis between Japan and the U.K. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(10):1916–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan AR, Chapman PT, Stamp LK, Wells JE, O’Donnell JL. Wegener’s granulomatosis: treatment and survival characteristics in a high-prevalence southern hemisphere region. Intern Med J. 2012;42(4):e23–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts RA, Mooney J, Skinner J, Scott DG, Macgregor AJ. The contrasting epidemiology of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) and microscopic polyangiitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(5):926–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto S, Uezono S, Hisanaga S, Fukudome K, Kobayashi S, Suzuki K, et al. Incidence of ANCA-associated primary renal vasculitis in the Miyazaki Prefecture: the first population-based, retrospective, epidemiologic survey in Japan. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1016–22. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01461005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hissaria P, Cai FZ, Ahern M, Smith M, Gillis D, Roberts-Thomson P. Wegener’s granulomatosis: epidemiological and clinical features in a South Australian study. Intern Med J. 2008;38(10):776–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ntatsaki E, Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36(3):447–61. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammad AJ, Jacobsson LT, Westman KW, Sturfelt G, Segelmark M. Incidence and survival rates in Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome and polyarteritis nodosa. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(12):1560–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng B, Specks U, Offord KP, Matteson EL. Epidemiology of Wegener granulomatosis since the introduction of ANCA testing in Olmsted County, MN, 1990-1999. J Clin Rheumatol. 2003;9(6):387–8. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000089786.10614.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotch MF, Hoffman GS, Yerg DE, Kaufman GI, Targonski P, Kaslow RA. The epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Estimates of the five-year period prevalence, annual mortality, and geographic disease distribution from population-based data sources. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(1):87–92. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rottem M, Fauci AS, Hallahan CW, Kerr GS, Lebovics R, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis in children and adolescents: clinical presentation and outcome. J Pediatr. 1993;122(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohm M, Gonzalez Fernandez MI, Ozen S, Pistorio A, Dolezalova P, Brogan P, et al. Clinical features of childhood granulomatosis with polyangiitis (wegener’s granulomatosis) Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabral DA, Canter DL, Muscal E, Nanda K, Wahezi DM, Spalding SJ, et al. Comparing Presenting Clinical Features in 48 Children With Microscopic Polyangiitis to 183 Children Who Have Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Wegener’s): An ARChiVe Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(10):2514–26. doi: 10.1002/art.39729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grisaru S, Yuen GW, Miettunen PM, Hamiwka LA. Incidence of Wegener’s granulomatosis in children. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(2):440–2. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce FA, Grainge MJ, Lanyon PC, Watts RA, Hubbard RB. The incidence, prevalence and mortality of granulomatosis with polyangiitis in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(4):589–96. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akikusa JD, Schneider R, Harvey EA, Hebert D, Thorner PS, Laxer RM, et al. Clinical features and outcome of pediatric Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):837–44. doi: 10.1002/art.22774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arulkumaran N, Jawad S, Smith SW, Harper L, Brogan P, Pusey CD, et al. Long- term outcome of paediatric patients with ANCA vasculitis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2011;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iudici M, Puechal X, Pagnoux C, Quartier P, Agard C, Aouba A, et al. Brief Report: Childhood-Onset Systemic Necrotizing Vasculitides: Long-Term Data From the French Vasculitis Study Group Registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1959–65. doi: 10.1002/art.39122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stegmayr BG, Gothefors L, Malmer B, Muller Wiefel DE, Nilsson K, Sundelin B. Wegener granulomatosis in children and young adults. A case study of ten patients. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(3):208–13. doi: 10.1007/s004670050043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belostotsky VM, Shah V, Dillon MJ. Clinical features in 17 paediatric patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17(9):754–61. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0914-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacri AS, Chambaraud T, Ranchin B, Florkin B, See H, Decramer S, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of childhood-onset ANCA-associated vasculitis: a French nationwide study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(Suppl 1):i104–12. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James KE, Xiao R, Merkel PA, Weiss PF. Clinical course and outcomes of childhood-onset granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(Suppl 103(1)):202–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–67. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Watson RS. Trends in the epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(7):686–93. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182917fad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stone JH, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Min YI, Uhlfelder ML, Hellmann DB, et al. A disease-specific activity index for Wegener’s granulomatosis: modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS) Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(4):912–20. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<912::AID-ANR148>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellmich B, Flossmann O, Gross WL, Bacon P, Cohen-Tervaert JW, Guillevin L, et al. EULAR recommendations for conducting clinical studies and/or clinical trials in systemic vasculitis: focus on anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):605–17. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahr AD, Neogi T, Merkel PA. Epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis: Lessons from descriptive studies and analyses of genetic and environmental risk determinants. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(2 Suppl 41):S82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morishita KA, Moorthy LN, Lubieniecka JM, Twilt M, Yeung RSM, Toth MB, et al. Early Outcomes in Children With Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(7):1470–9. doi: 10.1002/art.40112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson A, Stamp LK, Chapman PT, O’Donnell JL. The epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis in a Southern Hemisphere region. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(5):624–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearce FA, Lanyon PC, Grainge MJ, Shaunak R, Mahr A, Hubbard RB, et al. Incidence of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a UK mixed ethnicity population. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55(9):1656–63. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holle JU, Gross WL, Latza U, Nolle B, Ambrosch P, Heller M, et al. Improved outcome in 445 patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis in a German vasculitis center over four decades. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):257–66. doi: 10.1002/art.27763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallace ZS, Lu N, Miloslavsky E, Unizony S, Stone JH, Choi HK. Nationwide Trends in Hospitalizations and In-Hospital Mortality in Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Wegener’s) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69(6):915–21. doi: 10.1002/acr.22976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flossmann O, Berden A, de Groot K, Hagen C, Harper L, Heijl C, et al. Long-term patient survival in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):488–94. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallace ZS, Lu N, Unizony S, Stone JH, Choi HK. Improved survival in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: A general population-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4):483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luqmani R, Suppiah R, Edwards CJ, Phillip R, Maskell J, Culliford D, et al. Mortality in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a bimodal pattern. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(4):697–702. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahr A, Girard T, Agher R, Guillevin L. Analysis of factors predictive of survival based on 49 patients with systemic Wegener’s granulomatosis and prospective follow-up. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40(5):492–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koldingsnes W, Nossent H. Predictors of survival and organ damage in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41(5):572–81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bligny D, Mahr A, Toumelin PL, Mouthon L, Guillevin L. Predicting mortality in systemic Wegener’s granulomatosis: a survival analysis based on 93 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(1):83–91. doi: 10.1002/art.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiner M, Goh SM, Mohammad AJ, Hruskova Z, Tanna A, Bruchfeld A, et al. Outcome and treatment of elderly patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1128–35. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00480115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krafcik SS, Covin RB, Lynch JP, 3rd, Sitrin RG. Wegener’s granulomatosis in the elderly. Chest. 1996;109(2):430–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sreih AG, Annapureddy N, Springer J, Casey G, Byram K, Cruz A, et al. Development and validation of case-finding algorithms for the identification of patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis in large healthcare administrative databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(12):1368–74. doi: 10.1002/pds.4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.