Abstract

Pasteurella multocida, which colonizes upper respiratory and digestive tracts, is a leading cause of respiratory diseases in many host species. Here, we describe a case of P. multocida pneumonia with hemoptysis. A 72-year-old female diagnosed with bronchiectasis with a 36-year history presented with a worsened infiltrative and granular shadow in the lower right lobe and lingular segment. Bronchial lavage fluid culturing suggested Pasteurella pneumonia. P. multocida was confirmed by 16S rRNA sequencing. The patient was readmitted to our hospital because of hemoptysis, and she was treated successfully with antibiotic therapy. The possibility of P. multocida infection must be considered in patients who own pets.

Keywords: Pasteurella multocida, Pasteurella canis, Hemoptysis, Pasteurellosis

1. Introduction

Pasteurella multocida, a small gram-negative coccobacilli belonging to the Pasteurellae family, colonizes the upper respiratory and digestive tracts of several wild and domestic mammals [1,2]. P. multocida is also known to be a zoonotic agent in humans [3]. The commonest human infections caused by Pasteurella are local wound infections resulting from animal bites and scratches. This infection also has been reported to cause severe complications, such as septic arthritis, meningitis, peritonitis, sepsis, abscess, and pneumonia [[1], [2], [3]]. Pasteurellosis is also caused by licks on skin abrasions and due to contact with mucous secretions derived from pets. The respiratory tract is the second most common site of P. multocida infection; P. multocida is usually recognized as a commensal organism in patients with chronic pulmonary disease. However, in some cases of pulmonary pasteurellosis, serious respiratory tract infections can develop and can be fatal [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Here, we report the case of P. multocida pneumonia in a 72-year-old female with bronchiectasis and worsening hemoptysis.

2. Case report

A 72-year-old Japanese female was admitted to Tsukuba University Hospital (Tsukuba, Japan) in September 2015 with aggravation of consolidation in the lingular segment. She had never smoked; however, she had a 36-year history of bronchiectasis in the lower right lobe and lingular segment with several episodes of hemosputum. She also received clopidogrel to maintain a stent inserted for cerebral aneurysm. She had pet cats and slept with them for almost 30 years.

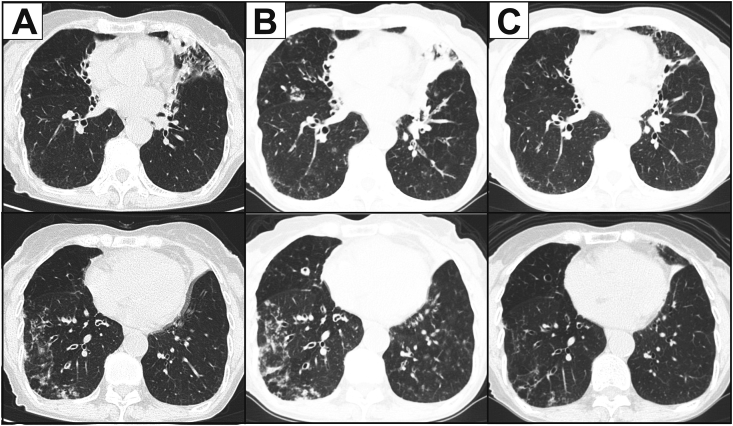

Physical examination at admission was unremarkable. Laboratory findings, including white blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels, were normal. T-SPOT.TB test for tuberculosis and serum anti-Mycobacterium avium complex antibody level was negative. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed worsened bronchodilation, bronchial wall thickness, centrilobular nodules, and air-space consolidation in the lower right lobe and lingula (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

CT images indicate bronchodilation, thickness of the bronchial wall, centrilobular granular shadow, and consolidation in the lingular and right S8 segments (A). Both of these lesions became worse when the patient suffered hemoptysis (B) and then improved after antibiotic treatment.

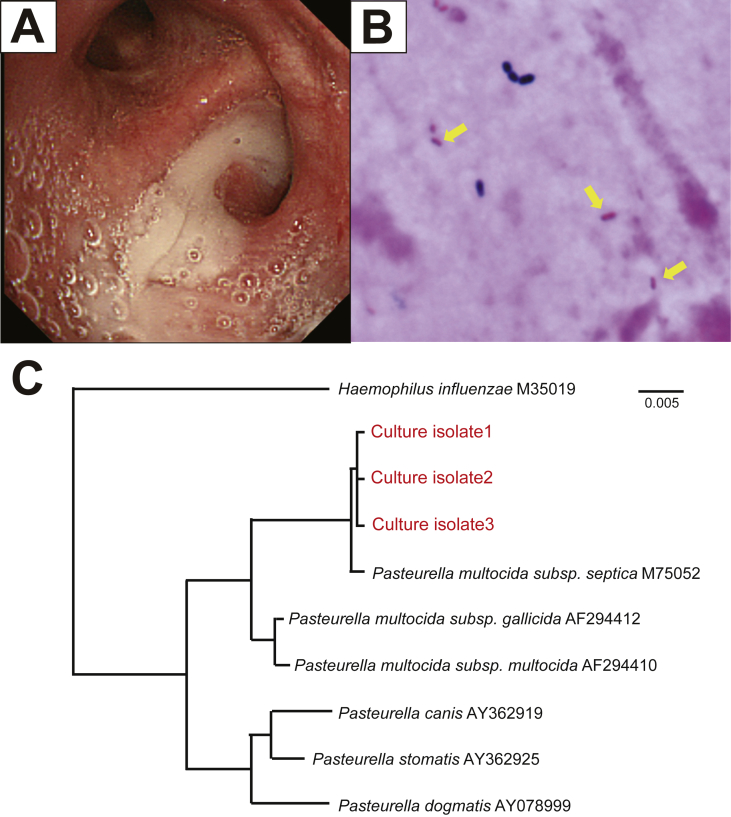

Bronchoscopy was performed to confirm the pathogen identity. A large amount of purulent sputum was observed in the lingular segments (Fig. 2A). Cultures of wash specimens from the right B8a and lingular segments revealed gram-negative rods (Fig. 2B), which using Vitek 2 testing, were identified as P. canis with a 91% identification probability. In addition, culturing using MacConkey agar was negative for bacterial growth; isolated bacteria could not dissolve maltose and mannitol, but could dissolve ornithine. These results were consistent with those obtained for P. canis. Because P. canis quite rarely causes pneumonia, we performed 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing for confirming the diagnosis; the isolates were identified as P. multocida subsp. septica with a 99.9% probability (Fig. 2C). Based on these results, P. multocida pneumonia was finally diagnosed. While waiting for the rRNA sequencing analysis results, the patient suffered worsened hemoptysis and was readmitted to our hospital in October (Fig. 1B). Intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam (9.0 g/day) was administered for one week, followed by oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (750 mg/day) for another 30 days. After antibiotic therapy, the lower right lobe and lingular shadows were extremely improved (Fig. 1C). She was discharged on day 25 without any complications. Before discharge, we instructed her to strictly wash her hands after contact with her cats; we also instructed her to keep the cats away from her bed. We followed-up with her two years after her discharge, during which she had no symptoms of hemosputum related to pasteurellosis. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the case details and associated images.

Fig. 2.

Bronchoscopy indicates a large amount of purulent sputum from the lingular segments (A). Gram staining revealed gram-negative rods in the bronchial wash specimen (B). Phylogenetic relationship of the Pasteurella species isolated from the culture (C). The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences from culture isolates were compared with the GenBank database using BLAST searches. In 1354 base pairs of the 16S rRNA gene sequences, the isolates showed a 99.9% identity match with the GenBank sequence M75052 (P. multocida subsp. septica). Bar = 0.5% sequence divergence.

3. Discussion

Pasteurella species is highly prevalent among animal populations. Previous literature has suggested that 20–30 human deaths occur every year worldwide because of pasteurellosis [2]. Although P. multocida occasionally colonizes immunocompetent patients, pneumonia due to P. multocida is rare [2,5,6]. In 1993, Kopita et al. studied the characteristics of 108 patients (mean age, 62 years; 65% male) with Pasteurella pleuropulmonary infection [1]. The common primary illnesses were pneumonia (45.3%), tracheobronchitis (34%), empyema (23%), and lung abscess (3%) [1]. Most of the patients had underlying pulmonary diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, lung carcinoma, and pulmonary fibrosis [1]. The mortality rate of patients with Pasteurella pleuropulmonary infection was documented as 30% [1]. Complications of hemoptysis have not been noted frequently. To the best of our knowledge, only three hemoptysis cases have been reported in the literature; most of these patients had a lung abscess with P. multocida infection [[7], [8], [9]]. Because our patient had a history of bronchiectasis and because culture samples obtained from separate bronchial washings revealed P. multocida infection at both sites, chronic Pasteurella infection may have affected the hemoptysis episodes. However, the identification of clinical Pasteurella isolates by Vitek 2 is controversial. Zangenah et al. reported that Vitek 2 could only identify 48.5% of Pasteurella isolates correctly and failed to identify P. multocida in more than 50% of the cases [10]. Although Vitek 2 is a rapid and useful diagnosis system, a different confirmation approach is recommended before final diagnosis. P. multocida isolates are classified into five capsular types and eight lipopolysaccharide (LPS) types [11,12]. Multiplex PCR for capsular and LPS typing, is a fast, simple, and cheap method for genotyping [11,12]. Although the mechanism by which these type differences affect strain virulence and host immunity remains unclear, rapid and accurate species identification can contribute to epidemiological tracing of outbreak strains [13].

P. multocida is not susceptible to dicloxacillin, cephalexin, erythromycin, and clindamycin [2]. Of note, combination treatment with amoxicillin and β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid is effective [2]. Although the treatment duration should be decided based on disease severity, at least 10–14 days of antibiotic treatment is recommended [1]. A previous study has reported that there is no correlation between length of exposure and disease severity [1]. However, a recent study has suggested that pet owners who have more frequent close contact with dying animals are at risk for invasive P. multocida infection [4]. Because disease severity was thought to be associated with underlying disease, the education of elderly or high-risk patients might be useful to avoid fatal pasteurellosis and its complications. In our case, P. multocida pneumonia was successfully treated with β-lactam antibiotics for 5 weeks. We also educated the patient to avoid close contact with her pets and thereby successfully prevent recurrent hemoptysis.

In conclusion, we described a rare case of P. multocida pneumonia with hemoptysis. The patient was successfully treated with antibiotic therapy. The number of elderly persons who own domestic animals is increasing in Japan. It is important to consider the possibility of P. multocida infection and to check whether patients keep household pets.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hitomi Shigemi, Professor of Infectious Diseases, University of Tsukuba, for his help in confirming the diagnosis by 16S rRNA sequencing.

References

- 1.Kopita J.M., Handshoe D., Kussin P.S. Cat germs! Pleuropulmonary pasteurella infection in an old man. N. C. Med. J. 1993;54:308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson B.A., Ho M. Pasteurella multocida: from zoonosis to cellular microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013;26:631–655. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00024-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seki M., Sakata T., Toyokawa M. A chronic respiratory pasteurella multocida infection is well-controlled by long-term macrolide therapy. Intern. Med. 2016;55:307–310. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers E.M., Ward S.L., Myers J.P. Life-threatening respiratory pasteurellosis associated with palliative pet care. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2012;54:e55–e57. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira J., Treger K., Busey K. Pneumonia and disseminated bacteremia with Pasteurella multocida in the immune competent host: a case report and a review of the literature. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2015;15:54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pradeepan S., Tun Min S., Lai K. Occupationally acquired Pasteurella multocida pneumonia in a healthy abattoir worker. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2016;19:80–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sazon D.A., Hoo G.W., Santiago S. Hemoptysis as the sole presentation of Pasteurella multocida infection. South. Med. J. 1998;91:484–486. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maneche H.C., Toll H.W., Jr. Pulmonary cavitation and massive hemorrhage caused by pasteurella multocida. Report of a case. N. Engl. J. Med. 1964;271:491–494. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196409032711003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt E.C., Truitt L.V. Koch ML Pulmonary abscess with empyema caused by Pasteurella multocida. Report of a fatal case. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1970;54:733–736. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/54.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zangenah S., Guleryuz G., Borang S. Identification of clinical Pasteurella isolates by MALDI-TOF -- a comparison with VITEK 2 and conventional microbiological methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;77:96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper M., John M., Turni C. Development of a rapid multiplex PCR assay to genotype Pasteurella multocida strains by use of the lipopolysaccharide outer core biosynthesis locus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:477–485. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02824-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townsend K.M., Boyce J.D., Chung J.Y. Genetic organization of Pasteurella multocida cap Loci and development of a multiplex capsular PCR typing system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39:924–929. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.924-929.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dziva F., Muhairwa A.P., Bisgaard M. Diagnostic and typing options for investigating diseases associated with Pasteurella multocida. Vet. Microbiol. 2008;128:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]