Abstract

Vector-borne diseases account for more than 17% of all infectious diseases, causing more than one million deaths annually. Malaria remains one of the most important public health problems worldwide. These vectors are bloodsucking insects, which can transmit disease-producing microorganisms during a blood meal. The contact of culicids with human populations living in malaria-endemic areas suggests that the identification of Plasmodium genetic material in the blood present in the gut of these mosquitoes may be possible. The process of assessing the blood meal for the presence of pathogens is termed ‘xenosurveillance’. In view of this, the present work investigated the relationship between the frequency with which Plasmodium DNA is found in culicids and the frequency with which individuals are found to be carrying malaria parasites. A cross-sectional study was performed in a peri-urban area of Manaus, in the Western Brazilian Amazon, by simultaneously collecting human blood samples and trapping culicids from households. A total of 875 individuals were included in the study and a total of 13,374mosquito specimens were captured. Malaria prevalence in the study area was 7.7%. The frequency of households with at least one culicid specimen carrying Plasmodium DNA was 6.4%. Plasmodium infection incidence was significantly related to whether any Plasmodium positive blood-fed culicid was found in the same household [IRR 3.49 (CI95% 1.38–8.84); p = 0.008] and for indoor-collected culicids [IRR 4.07 (CI95%1.25–13.24); p = 0.020]. Furthermore, the number of infected people in the house at the time of mosquito collection was related to whether there were any positive blood-fed culicid mosquitoes in that household for collection methods combined [IRR 4.48 (CI95%2.22–9.05); p<0.001] or only for indoor-collected culicids [IRR 4.88 (CI95%2.01–11.82); p<0.001]. Our results suggest that xenosurveillance can be used in endemic tropical regions in order to estimate the malaria burden and identify transmission foci in areas where Plasmodium vivax is predominant.

Author summary

In the era of malaria elimination, novel surveillance strategies are needed in order to achieve and sustain malaria free status in the region. New malaria infection burden surveillance strategies should be simple to implement, technologically uncomplicated, cost-effective and applicable to areas where malaria cases are known to occur. In this context, the xenosurveillance is an important tool, especially when using widely distributed and anthropophilic mosquitoes. Culex mosquitoes do not transmit malaria, but due to their wide dispersion and anthropophilic behavior, may be used for the monitoring of certain vector-borne diseases, such as malaria, whose agent can be easily identified through molecular techniques in the ingested blood. Here, we evaluated a Plasmodium xenosurveillance approach to determine human malaria prevalence in three distinct peri-urban areas of Manaus. For this purpose, we evaluated the presence of Plasmodium DNA in engorged culicids sampled indoors regardless of their role in malaria transmission and compared them with the human infection status in the same households. The spatial correlation between the presence of Plasmodium DNA in mosquitoes was similar to the infection rate in humans which clearly indicates that xenosurveillance can be a complimentary strategy in endemic tropical regions in order to estimate the malaria burden.

Introduction

Vector-borne diseases account for more than 17% of all infectious diseases, and cause more than one million deaths annually. Vectors are living organisms that can transmit infectious diseases between humans or from animals to humans. These vectors are bloodsucking insects, which ingest disease-producing microorganisms during a blood meal from an infected host (human or animal) and can subsequently inject them into a new host during a new blood meal. Mosquitoes are among the best-known disease vectors. Three genera are responsible for transmitting a series of life-threatening diseases worldwide, however mostly in tropical areas: 1) Aedes: vector of Chikungunya, dengue, Zika, Rift Valley and yellow fever; 2) Anopheles: vector of malaria, Saint Louis encephalitis, West Nile fever and several Anopheles A and B orthobunyaviruses and 3) Culex: Japanese encephalitis, lymphatic filariasis, Saint Louis encephalitis, Oropouche and West Nile fever [1,2].

Many of these diseases are preventable through informed, protective measures. Surveillance is critical for the prediction of future disease outbreaks and epidemics at an early stage, as well as for identifying transmission hotspots. Among vector-borne diseases, malaria remains one of the most important public health problems worldwide. It is estimated that malaria transmission still occurs in 91 countries and territories of the world, and causes an estimated 216 million clinical episodes and around 445,000 deaths globally every year [3]. An unknown, and much higher, number of individuals in malaria-endemic areas silently carry malaria parasites, which provides a reservoir for malaria transmission. The challenge of identifying them has been recognized as a major difficulty in regard to the adequate control and eventual elimination of malaria [4].

The majority of mosquito species is hematophagous, and relies on blood from vertebrates for nourishment and reproduction. When engorged, mobility is limited and they can be easily collected via aspiration. Blood meal analysis is then carried out in order to detect the presence of pathogens, a process termed ‘xenosurveillance’ [5,6]. Experimentally, mosquitoes can be used as biological syringes’ so we can accurately quantify the presence of viruses or other microorganisms in their midgut and also evaluate the potential role of small vertebrates in the transmission cycle of arboviruses [7]. Such methods have shown, for instance, transmission of human pathogens, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) [8,9] and dengue virus (DENV) by Culex quinquefasciatus [10] and hepatitis C virus (HCV) by Culex pipiens complex [11,12]. Field studies have confirmed that vertebrate viral pathogens that are not vector-borne could also be detected in the blood meals of mosquitoes belonging to a variety of taxa [13,14]. H5N1 virus sequences were found in blood-engorged mosquitoes collected near a poultry farm during an outbreak of avian influenza in Thailand [15]. To survey DENV and Japanese encephalitis circulation in this same country, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detected virus-reactive antibodies in blood meals collected from culicids irrespective of the mosquito species’ ability as a vector [16]. Nucleic acid sequences from human papillomavirus 23 (HPV23), human herpesvirus 1 and human papillomavirus type 112 (HPV112) were identified in mosquito samples from San Diego, California [17]. In Central Brazil, DENV-4 was detected in several culicids, especially Cx. quinquefasciatus [18]. In Liberia, An. gambiae bloodfed mosquitoes resting indoors were found positive for human skin-associated microbes (e.g. Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and canine distemper virus (CDV) signatures [6]. Human bacterial pathogens such as Rickettsia spp. [19,20], Francisella tularensis [21] and Borrelia [22,23] were also found in field-collected culicids.

In the case of malaria, clinical, parasitological and serological markers of transmission, as detected in humans, have been routinely and historically used to detect transmission pockets and guide hotspot-targeted interventions. However, in more recent times, interest has also shifted to evaluating transmission through the exploration of the burden of low-density (formerly described as “asymptomatic” albeit now recognized to be potential causes of more silent, but still important, clinical consequences) infections in low transmission areas [24–27]. Nevertheless, current malaria surveillance systems can be expensive, laborious and useless for sampling numbers of exposed individuals over space and time. In Liberia, a pathogen surveillance strategy using xenosurveillance has found the presence of P. falciparum in An. gambiae; however, this result was expected since malaria is holoendemic in this region and therefore the mosquito or/and the human upon which it fed may be infected [6].

Fauver et al. [9] have demonstrated the viability of xenosurveillance as a tool for sampling human blood in order to detect circulating pathogens. However, to the best of our knowledge, xenosurveillance of malaria using highly anthropophilic culicids, frequently more abundant than anophelines, has been never validated in regards to its fundamental utility, feasibility in field timeframes and technically relevant concentrations. In this work, we hypothesized that, in this surveillance approach, molecular detection of Plasmodium in blood fed mosquitoes reflect the malaria burden and make malaria surveillance more feasible in tropical localities where Culex is abundant.

Methods

Study site

This study was conducted in the Brasileirinho, Puraquequara and Ipiranga communities, in a peri-urban area of Manaus, Western Brazilian Amazon. According to a census carried out by the field team before the beginning of the study, approximately 2,400 inhabitants were living in the study area, of around 72 km2. The general characteristics of these communities were previously described [28,29].

Malaria infection status in humans

A cross-sectional sampling was performed from January to March, 2014by simultaneously collecting human blood samples and trapping culicids from 233 households located in this area. Sampling included all inhabitants living in these houses that were willing to participate in the study. For each study participant, a questionnaire was completed, containing personal malaria preventive measure information and the participants’ history of malaria episodes in the preceding 30 days (Table 1). Upon enrolment, a 300 μL blood sample was collected from the participant via finger puncture using Microtainer tubes containing EDTA and sodium fluoride (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA). In infants, blood was obtained by puncture of the heel or toe. All samples were frozen at -8°C until further processing.

Table 1. Characteristics of the households sampled for mosquito collections.

| Variable | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Community | ||

| Ipiranga | 103 | 44.2 |

| Brasileirinho | 81 | 34.8 |

| Puraquequara | 49 | 21.0 |

| Location | ||

| Main road | 84 | 36.1 |

| Side road | 149 | 63.9 |

| Number of residents | ||

| 1 | 83 | 31.8 |

| 2 | 64 | 24.5 |

| 3 | 37 | 14.2 |

| 4 | 25 | 9.6 |

| ≥5 | 52 | 19.9 |

| House building type | ||

| Brick | 133 | 57.1 |

| Wood | 100 | 42.9 |

| Walls | ||

| Complete | 221 | 94.9 |

| Partial | 12 | 5.1 |

| Cracks in the walls | ||

| No | 175 | 75.1 |

| Yes | 58 | 24.9 |

| Doors and windows | ||

| No | 3 | 1.3 |

| Yes | 230 | 98.7 |

| Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) | ||

| No | 181 | 77.7 |

| Yes | 52 | 22.3 |

| Indoor residual spraying (IRS) in the last 6 months | ||

| No | 126 | 54.1 |

| Yes | 107 | 45.9 |

| Insecticide-treated bednet use during the previous last night1 | ||

| No | 95 | 40.8 |

| Yes | 138 | 59.2 |

| Fever1,2 | ||

| No | 219 | 94.0 |

| Yes | 14 | 6.0 |

| Use of antimalarial drugs in the last 30 days2 | ||

| No | 203 | 87.1 |

| Yes | 30 | 12.9 |

1at least one resident presenting the variable

2body temperature above 37.5°C at the time of blood collection or in the past 48 hours.

In the case of symptoms related to malaria, a thick blood smear was prepared following the World Health Organization guidelines [30]. All participants that tested positive for P. falciparum and/or P. vivax by thick blood smear and/or qPCR were considered as infected by malaria parasites, and received treatment according to the guidelines of the Brazilian Ministry of Health [31].

Detection of Plasmodium spp.in human samples

Pelleted RBCs obtained from participants’ blood were resuspended in PBS and genomic DNA was extracted using a FavorPrep 96-well Genomic DNA Kit (Favorgen, Ping-Tung, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eluted in elution buffer and stored at -20°C or vacuum concentrated (Concentrator 5301, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) [32].

All DNA samples were subjected to QMAL Taqman qPCR in order to detect any Plasmodium spp. by targeting a conserved region of the 18S rRNA gene [30]. QMAL-positive samples were further analysed by Taqman qPCR assays to detect species-specific sequences of 18S rRNA gene of P. falciparum and P. vivax, as previously described [32,33]. PCR assays were carried out on the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA).

Culicidtrapping and identification

In each household, mosquitos were collected using BG-Sentinel traps with BG-Lure attractant and electric entomological aspirators (Horst Armadilhas Ltda., Brazil). One BG-Sentinel per house was left generally in a bedroom for around 24 hours. Aspiration inside the dwellings lasted approximately 5 to 15 minutes, depending on the number and size of the rooms. In the collection period, average temperature was 27.4°C (23.4°C- 30.8°C). The captured culicids were transferred by suitable plastic cages to the FMT-HVD Entomology Laboratory on the same day. The mosquitoes were placed on petri dishes arranged on ice, immediately identified in a dormant state and separated by sex and blood-feeding status (engorged or not). Taxonomical identification was made using the keys of Consoli and Lourenço-de-Oliveira [34], and Faran and Linthicum [35]. After the identification, engorged female mosquitos were stored individually in ethanol 80% v/v at -20°C until DNA extraction.

Standardization of Plasmodium DNA detection from engorged culicids

The number of mosquitoes per pool and the maximum post-feeding time in which Plasmodium DNA detection is still possible were determined by using experimentally fed culicids. A colony of Cx. quinquefasciatus was established from immature forms (larvae and pupae) of the mosquitoes collected in natural breeding environments on the outskirts of the city. Cx. quinquefasciatus, the most abundant mosquito species found on the outskirts of Manaus [36], was chosen for this purpose. These were maintained under standard insectary conditions of 27°C, 80% relative humidity, and a 12:12 light/dark cycle until we obtained adult F1 generation, according to Gerberg et al. methodology [37]. 100 to 120 5-day-old female mosquitoes were given a blood meal with P. vivax obtained from a volunteer’s blood, using an artificial membrane feeding system [38]. After feeding, 50 fully engorged females were immediately sacrificed by freezing at -20°C. The remaining fully engorged females were returned to insectary conditions, and subsequent samples of 10 mosquitoes were sacrificed daily from day 1 (D1) to 10 (D10) after a P. vivax blood meal. In order to estimate the maximum number of mosquitos per pool for Plasmodium sp. detection, different proportions of infected blood fed per non-infected blood fed mosquitos were assessed: 1:1; 1:3; 1:5; 1:7; and 1:9. For this assay, only abdomens were used for DNA extraction and QMAL q-PCR.

DNA extraction from mosquitos

DNA extraction was performed according to Musapa et al. [39] by using a 5% w/v Chelex 100 Resin (styrene divinylbenzene copolymer containing paired iminodiacetate ions; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). All DNA samples were subjected to QMAL Taqman qPCR to detect Plasmodium spp. by targeting a conserved region of the 18S rRNA gene [32,33].

Data analysis

The design of the standardized forms, and their scanning, processing and exporting to Excel sheets was performed using Cardiff Teleform v. 10.4.1 (Cardiff Software). Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 13.1 and QGis v. 2.18.7. Since houses were used as unit of analysis, information on building conditions, spatial coordinates, demography and infection status in both human and mosquitos were clustered by household.

Relative frequency of Plasmodium DNA presence in culicids was determined by the number of positive pools with QMAL q-PCR genus-specific amplification per total number of pools from the same household. Similarly, the human infection rate was calculated as the proportion of QMAL q-PCR genus-specific positive per total of samples assessed for each household. Although the number of copies could be obtained from both tests, the data was dichotomized as positive or negative for analysis purposes. Negative binomial regression was used to assess association between presence of any positive blood-fed Culex in a household and two distinct variables: (i) the total number of new infections per time at risk (incidence); and (ii) number of people infected at the time of mosquito collection in the household (i.e., household prevalence). Additionally, the same models were carried out using the total number of blood-fed Culex mosquitoes as independent variable. Differences were considered statistically significant for p<0.05.

Ethics statement

Colonised Cx. quinquefasciatus blood feeding on Mus musculus was approved by the FMT-HVD Ethics Committee in Animal Research (349.211/2013). The human survey was approved by the Brazilian National Committee of Ethics (349.211/2013). An informed consent form was signed by all study participants or by a parent or legal guardian. Children between 12 and 17 years signed an additional assent form. Malaria patients were treated according the Brazilian Ministry of Health guidelines [31].

Results

Individual and household characteristics

A total of 875 individuals were included in the study, and nearly half of them (45.6%) were 0 to 20 years old and 50.7% were women. A total of 381 (43.5%) individuals reported to use long-lasting insecticidal nets in the preceding night and 556 (63.5%) reported that their houses had been sprayed with permethrin in the preceding six months. A total of 244 (27.9%) individuals reported no previous malaria episode, 252 (28.8%) reported 1 to 3 previous episodes and 379 (43.3%) reported having experienced more than 3 episodes in their lifetime. Malaria prevalence in the study area was 7.7%, ranging from 3.2% in the Brasileirinho community to 11.2% in the Puraquequara community. In the Ipiranga community, prevalence was 8.1%. Only 3 (4.1%) of the total 61 detected infections were symptomatic.

From the total of households included, 44.2% were located in the Ipiranga community, 34.76% in the Brasileirinho community and 21.03% in the Puraquequara community. The mean number of residents per household was 3, but ranged anywhere from 1 to 15. Regarding the household structure, bricks were mostly used for building (133; 57.1%), houses with complete walls (221; 94.9%). 58 (24.9%) of the houses presented cracks in the walls. 52 (22.3%) houses possessed long-lasting insecticidal nets, 107 (45.9%) had been sprayed in the last 6 months and 138 (59.2%) had at least one resident who had used long-lasting insecticide-treated nets during the previous night. Fever was documented in at least one resident in 14 (6%) of the households. Thirty (12.9%) households had at least one resident who had been using antimalarials in the last 30 days (Table 1).

Standardization of Plasmodium DNA detection from engorged culicids

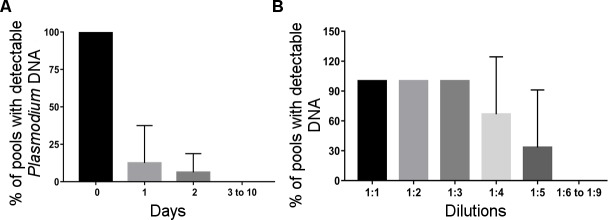

In the search for the definition of which field collection mosquitoes should be used for the genus-specific qPCR assays, experimental infections were performed using Cx. quinquefasciatus from a pre-established colony. Plasmodium DNA was detectable at D2 post-feeding, when the Plasmodium DNA carriage was reduced to 12.5%. For this, we chose to test only visibly blood-fed mosquitoes. Detection using qPCR was possible up to a pool size of 5 mosquitos (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Standardization of Plasmodium DNA detection from engorged culicids.

Plasmodium DNA was detectable at D2 post-feeding (A) and 1:5 mosquito pool size (B).

Culicids abundance and Plasmodium DNA positivity

A total of 13,374 specimens were captured: 12,132 (90.7%) by using BG-Sentinel traps and 1,242 (9.3%) b electric aspirators. Most of the mosquitoes (n = 12,923; 96.6%) were Culex spp. with Cx. quinquefasciatus being the most common species (n = 12,599; 94.2%). 293 of the culicids (2.2%) were not identified. The mean number of culicids per household was 50, and ranged from 0 to 887 specimens; in 76.6% of the households 0–50 culicids were collected, and 6.1% presented more than 150 culicids. BG-Sentinel traps (12,132; 90.7%) were more effective in capturing mosquitoes and culicid diversity was greater (at least 10 taxa) when compared to electric aspiration (at least 6 taxa). Cx. quinquefasciatus predominated in the BG-Sentinel traps (95.3%) and the electric aspiration (83.6%) collections.

A proportion of 17.7% of the culicids were engorged, ranged from 14.5% in BG-Sentinel trapped specimens to 48.1% in those collected by electric aspirations (Chi-square 875.09, p<0.0001). For Cx. quinquefasciatus, 16.2% of the culicids were engorged, with 13.8% of BG-Sentinel trapped specimens and 42.0% of culicids from aspirations (Chi-square 557.08, p<0.001) (Table 2). The mean number of engorged culicids per household was 7.7, ranging from 0 to 176 specimen. A total of 198 households (75.9%) possessed at least one engorged mosquito in the collected specimens. The majority of the households possessed 1–5 engorged mosquitoes (121; 46.4%).

Table 2. Frequency of culicids collected according to trapping method.

| Culicid taxon | Electric aspirators | BG-Sentinel traps | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Blood-fed specimens (%) | Number | Blood-fed specimens (%) | Number | Blood-fed specimens (%) | |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 1,038 | 436 (42.0) | 11,561 | 1,601 (13.8) | 12,599 | 2,037 (16.2) |

| Culex sp. | 98 | 82 (83.7) | 225 | 77 (34.2) | 323 | 159 (49.2) |

| Unidentified culicids | 89 | 71 (79.8) | 204 | 70 (34.3) | 293 | 141 (48.1) |

| Anopheles darlingi | 12 | 6 (50.0) | 122 | 16 (13.1) | 134 | 22 (16.4) |

| Anopheles sp. | 1 | 0 (0) | 6 | 0 (0) | 7 | 0 (0) |

| Psorophora sp. | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 4 | 2 (50.0) |

| Uranotaenia sp. | 0 | . . . | 4 | 0 (0) | 4 | 0 (0) |

| Limatus sp. | 0 | . . . | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 | 0 (0) |

| Aedeomyia sp. | 0 | . . . | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) |

| Coquillettidia sp. | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) |

| Culex (Anoedioporpa) | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) |

| Culexspisseps | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | . . . | 1 | 1 (100.0) |

| Psorophora albigenu | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0 (0) |

| Toxorhynchitinae | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) |

| Total | 1,242 | 598 (48.1) | 12,132 | 1,764 (14.5) | 13,374 | 2,362 (17.7) |

Two household parameters affected the total number of mosquitoes captured indoors (Table 3): wooden houses (IRR 1.44, CI95%1.04–2.01; p = 0.029) and houses with cracks in the walls (IRR 1.38, CI95% 0.98–1.95; p = 0.067). Houses located in the Ipiranga community generally yielded less mosquitoes in comparison to houses located in the Puraquequara community (IRR 0.64, CI95% 0.44–0.93; p = 0.020). The differences were insignificant when only engorged culicids were analysed. However, the number of engorged mosquitoes was moderately associated with the number of total mosquitoes per house (p<0.0001, R2 = 0.37).

Table 3. Association of house parameters with total number of mosquitoes and number of blood-fed mosquitoes captured during indoor collections (negative binomial model).

| Total culicid number | Total culicid number | Blood-fed culicid number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (CI 95%) | P | IRR (CI 95%) | p | |

| House building type | ||||

| Brick | 1 | 1 | ||

| Wood | 1.44 (1.04–2.01) | 0.029 | 0.98 (0.63–1.54) | 0.938 |

| Cracks in the walls | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.38 (0.98–1.95) | 0.067 | 0.98 (0.61–1.59) | 0.954 |

| Community | ||||

| Ipiranga | 1 | 1 | ||

| Brasileirinho | 0.82 (0.57–1.18) | 0.286 | 0.79 (0.48–1.32) | 0.372 |

| Puraquequara | 0.64 (0.44–0.93) | 0.020 | 0.63 (0.38–1.05) | 0.074 |

Overall Plasmodium DNA positivity in engorged culicids was 2.9%, specifically, 3.2% in mosquitoes collected by electric aspiration and 2.7% collected by BG-Sentinel traps (Chi-square 0.1703, p = 0.679). Cx. quinquefasciatus showed a positivity rate of 3.4%, with no difference between collection methods (3.6% and 3.3%, respectively; Chi-square 0.0292, p = 0.864). Other Culex genus representatives (Culex sp.) showed a positivity rate of 3.7%, with no differences between collection methods (5.9% and 2.1%, respectively; Chi-square 0.8149, p = 0.367). Anopheles darlingi was found with Plasmodium DNA only in BG-Sentinel traps (1.9%). Other culicids did not present Plasmodium DNA positive samples (Table 4).

Table 4. Plasmodium DNA positivity in blood-engorged culicid pools according to species.

| Culicid taxon | Electric aspirators | BG-Sentinel traps | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pools | Plasmodium DNA positivity (%) | Number of pools | Plasmodium DNA positivity (%) | Number of pools | Plasmodium DNA positivity (%) | |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 169 | 3.6 | 428 | 3.3 | 597 | 3.4 |

| Culex sp. | 34 | 5.9 | 48 | 2.1 | 82 | 3.7 |

| Unidentified culicids | 28 | 0.0 | 53 | 0.0 | 81 | 0.0 |

| Anopheles darlingi | 12 | 0.0 | 53 | 1.9 | 65 | 1.5 |

| Anopheles sp. | 1 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.0 |

| Psorophora sp. | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0.0 |

| Culexspisseps | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0.0 |

| Psorophora albigenu | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0.0 |

| Toxorhynchitinae | 0 | . . . | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 |

| Total | 247 | 3.2 | 589 | 2.7 | 836 | 2.9 |

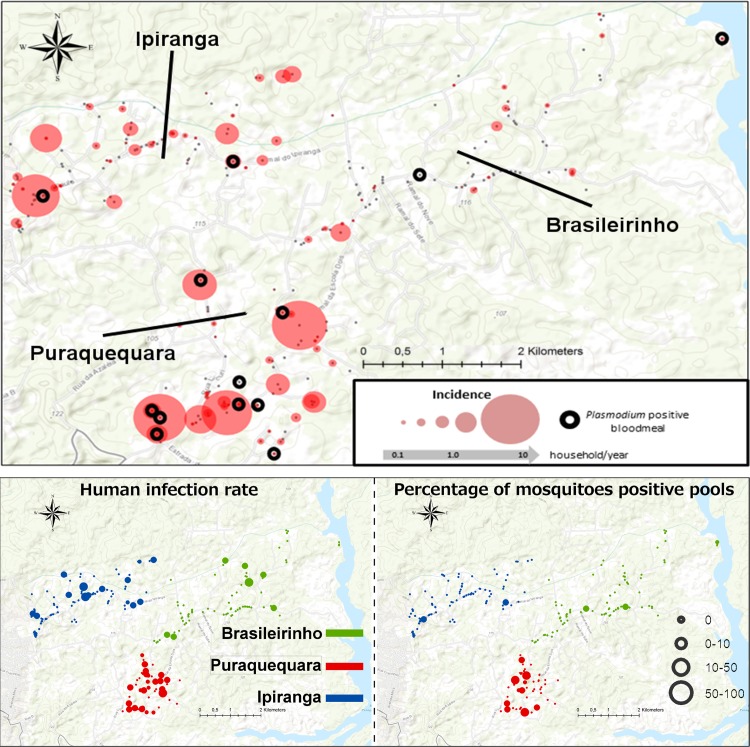

The frequency of households with at least one culicid specimen carrying Plasmodium DNA was 6.4%. Fig 2 indicates that culicids xenosurveillance was efficient in detecting malaria clusters at the study site. Out of the 14 households with at least one positive culicid, 8 (57%) showed an incidence>0 in humans and 31% had a Plasmodium infection incidence >0.

Fig 2. Spatial representation of human Plasmodium infection rate and proportion of Plasmodium DNA positive pools in the study area.

This study was conducted in the Brasileirinho, Puraquequara and Ipiranga communities, in a peri-urban area of Manaus, Western Brazilian Amazon. Culicid xenosurveillance was good in detecting malaria clusters in the study site, and demonstrated coinciding hotspots. This figure was created with Open Street Maps, which are licensed under ODBL 1.0.

Predicting malaria burden through the detection of Plasmodium DNA in Culex mosquitoes

Plasmodium infection incidence (as expressed in total number of new infections per household/time at risk) was significantly related to whether any Plasmodium positive blood-fed culicids were found in the same house when both collection methods were combined [IRR 3.49 (CI95% 1.38–8.84); p = 0.008] and for indoor-collected culicids [IRR 4.07 (CI95%1.25–13.24); p = 0.020] (Table 5).

Table 5. Association of blood-fed and Plasmodium DNA positive culicids and force of infection and prevalence of malaria in the study area.

| Number of culicids | Total culicids | Outdoor culicids | Indoor culicids | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (CI 95%) | P | IRR (CI 95%) | p | IRR (CI 95%) | p | |

| Plasmodium DNA positive culicids | ||||||

| Incidence | 3.49 (1.38–8.84) | 0.008 | 4.97 (0.43–57.67) | 0.200 | 4.07 (1.25–13.24) | 0.020 |

| Prevalence | 4.48 (2.22–9.05) | <0.001 | . . . | . . . | 4.88 (2.01–11.82) | <0.001 |

| Blood-fed culicids | ||||||

| Incidence | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.006 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 0.060 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.610 |

| Prevalence | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.220 | 1.04 (0.98–1.09) | 0.174 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.394 |

Furthermore, the number of people infected in the house at the time of mosquito collection was related to whether there were any positive blood-fed culicid mosquitoes in that house when both collection methods were combined [IRR 4.48 (CI95%2.22–9.05); p<0.001] or only for indoor-collected culicids [IRR 4.88 (CI95%2.01–11.82); p<0.001].

The total number of blood-fed culicids was also significantly associated with Plasmodium incidence (as expressed in total number of new infections per household/time at risk [1.03 (CI95% 1.01–1.05); p = 0.006].

Discussion

A large majority of mosquito species are hematophagous and rely on vertebrate blood for nourishment and reproduction. The contact of several anthropophilic and endophagic culicids with human populations living in malaria endemic areas suggests that the identification of Plasmodium genetic material in the blood present in the gut of mosquitoes may be possible and correlated to infection prevalence in the human population. In view of this, the present study investigated the relationship between Plasmodium DNA presence in engorged culicids and the frequency of individuals carrying malaria parasites in the same environment and the suitability of this novel xenosurveillancetool to support malaria transmission surveillance.

In this study, Cx. quinquefasciatus and other less frequent Culex species predominated in the mosquito collections. Some mosquito species, such as Cx. quinquefasciatus, have a spatial distribution and abundance, which is strongly dependent on human presence [36,40–44]. These mosquitoes are highly anthropophilic, feed frequently, and prefer to blood feed at night and often stay inside human dwellings [45–47]. Cx. quinquefasciatus, for example, are inclined to blood feed in the evening and evening twilight and they use human dwellings as shelter during the day and at night [40–42,48]. The feeding preference is for human blood and the behavior of Cx. quinquefasciatus, make this species very susceptible to pathogens present in the human host blood [6]. After the blood meal, the female mosquitoes have limited mobilityand rest on interior walls of houses for several hours, where they can be easily collected via aspiration. After capture, the blood contents present in the mosquito’s gut can be analyzed for the presence of different pathogens. Mosquitoes behave like “flying biological syringes” [36,48–52]. As these biological syringes are not competent vectors, replication is not expected [6,8,11–12,53,54] and the pathogen needs to be detected before complete digestion in the mosquito gut. During the study, we identified and separated mosquitoes by taxa to demonstrate the different possibilities for finding Plasmodium DNA. However, the identification is labour-intensive, though this may not be required when the proposed xenosurveillance method is used in operational settings.

A variable that needs to be taken into account in this xenosurveillance method is the sensitivity of Plasmodium detection in field-collected culicids. Through laser confocal microscopy, the development of P. falciparum in Cx. quinquefasciatus up to 30 hours after experimental infection was observed [55]. However, the authors point out that very few of the parasites in Cx. quinquefasciatus were alive during this period of 30 hours. The results obtained through the follow-up of P. vivax experimental feeding in Cx. quinquefasciatus demonstrated the decay of the DNA detection rates. The detection was only possible up to 48 hours after feeding. Since the mechanism of parasite killing must be sufficiently powerful that Plasmodium is not able to overcome it, working only with visibly engorged mosquitoes is a feasible, less costly and less laborious option, and the limit of five mosquito abdomens per pool demonstrates the operational viability of the technique. The simple cut of the abdomen of the mosquito does not require more time-consuming procedures and provides resource saving of DNA extraction and qPCR consumables, fundamental characteristics for the feasibility of any surveillance tool.

The presence of positive blood-fed culicids was significantly correlated to the force of infection and Plasmodium infection prevalence in humans. This correlation is important for combined collection methods and for indoor-collected culicids. In terms of logistics, using only indoor aspiration collection methods appeared to be more reliable. Although BG Sentinel traps are more productive, culicids collected by this method are mostly not engorged. BG Sentinel traps are large and difficult to carry to the field. The transportation requires vehicles with higher freight capacity and a second home visit for trap removal. Differently, the electric aspirators collect a greater proportion of engorged mosquitoes. This technique permits speed and practicality, allowing only one technician to aspire ~15 houses in one morning, in a single visit for culicid capture. Furthermore, the portability of the equipment with low requirement of logistics, allows the accomplishment of the visits even by motorcycle, which is deemed favourable in operational settings. However, in unfurnished and single-room homes, capture was usually poorly productive or even negative, which is probably due to the absence of mosquito resting sites. Considering that indoor aspiration may be considered by some as invasive, there was an expectation of rejection, which was not confirmed. Participants exhibited a good receptivity, even at times when some members of a family were still asleep.

In the force of infection analysis, the total number of blood-fed culicids was significantly associated with malaria infections. One explanation might be that some houses in poorer conditions are more permissive to Culex mosquitoes in parallel with higher odds to inhabitants who also have malaria. Unlike other studies, the samples of the present study were obtained in a seasonal period in which there was a lower prevalence of malaria, and in a single round of collections. Thus, the information generated may be important for estimating the circulation of the pathogen in the area, even in periods of low transmission, corroborating the possibility of using this tool as a new malaria indicator.

A good spatial correlation between Plasmodium DNA positive mosquitoes and infected humans was observed in the study area, where asymptomatic infection predominates. The existence of asymptomatic individuals who are carriers of Plasmodium sp. in significant proportions, even in a hypoendemic area, shows that the prevalence of infection, when based on the thick smear drops analyzed by microscopy, is underestimated. This indicates the importance of these reservoirs in the dynamics of malaria transmission, and suggests that the submicroscopic parasite may be important for the transmission between the high and low transmission seasonal periods [56,57]. Thus, alternatives to conventional surveillance and control measures should be implemented. In this context, the xenosurveillance method is a valuable complement to the official surveillance system.

New malaria infection burden surveillance strategies should be simple to implement, technologically uncomplicated, cost-effective and applicable to areas where malaria cases are known to occur. In this study, we found a significant association between blood-fed and Plasmodium DNA positive culicids and malaria prevalence. Our results suggest that xenosurveillance can be used in endemic tropical regions in order to estimate malaria burden and identify transmission foci in areas of a P. vivax asymptomatic carriers. As a perspective, this tool can be applied for the simultaneous surveillance of human pathogens, such as vector-borne, transmission areas overlapping with malaria, while taking advantage of the same collection efforts.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants and the technical staff from the Malaria and Entomology laboratory groups of FMT-HVD.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Counsel of Technological and Scientific development (CNPq), Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and Research Support Foundation of Amazonas (FAPEAM) through PPSUS and PAPAC projects supported this study. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has also funded this study through TransEpi Project. PFPP and MVGL are level 1 fellows from CNPq. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO. Vector-borne diseases. WHO. [Online] 04 29, 2018. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs387/en/.

- 2.Mohamed M, McLees A, Elliott RM. Viruses in the Anopheles A, Anopheles B, and Tete serogroups in the Orthobunyavirus genus (family Bunyaviridae) do not encode an NSs protein. J Virol. 2009;83(15):7612–8. 10.1128/JVI.02080-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. World malaria report 2017. WHO Libr Cat 2017 pp.196.

- 4.Sturrock HJW, Hsiang MS, Cohen JM, Smith DL, Greenhouse B, Bousema T, et al. Targeting asymptomatic malaria infections: active surveillance in control and elimination. PLoS Med. 2015;10(6):e1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann A, Nitsche A, Kohl C. Viral Metagenomics on Blood-Feeding Arthropods as a Tool for Human Disease Surveillance. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(10): E1743 10.3390/ijms17101743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubaugh ND, Sharma S, Krajacich BJ, Fakoli Iii LS, Bolay FK, Diclaro Ii JW, et al. Xenosurveillance: A Novel Mosquito-Based Approach for Examining the Human-Pathogen Landscape. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):e0003628 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kading RC, Biggerstaff BJ, Young G, Komar N. Mosquitoes used to draw blood for arbovirus viremia determinations in small vertebrates. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99342 10.1371/journal.pone.0099342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng YM, Liu D, Feng D, Tang H, Li Y, You X. An animal study on transmission of hepatitis B virus through mosquitoes. Chinese Med J. 1995;108(12):895–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauver JR, Weger-Lucarelli J, Fakoli LS III, Bolay K, Bolay FK, Diclaro JW II, et al. Xenosurveillance reflects traditional sampling techniques for the identification of human pathogens: A comparative study in West Africa. P PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(3):e0006348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vazeille-Falcoz M, Rosen L, Mousson L, Rodhain F. Replication of dengue type 2 virus in Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60(2):319–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang TT, Chang TY, Chen CC, Young KC,Roan JN, Lee YN, Cheng PN, Wu HL. Existence of Hepatitis C Virus in Culex quinquefasciatus after Ingestion of Infected Blood: Experimental Approach to Evaluating Transmission by Mosquitoes. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(9):3353–5. 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3353-3355.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan MI, Mangoud AM, Etewa S, Amin I, Morsy TA, El Hady G, El Besher ZM, Hammad KJ. Experimental demonstration of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in an Egyptian strain of Culex pipiens complex. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2003;33(2):373–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi C, Liu Y, Hu X, Xiong J, Zhang B, Yuan Z. A metagenomic survey of viral abundance and diversity in mosquitoes from Hubei province. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129845 10.1371/journal.pone.0129845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandler JA, Liu RM, Bennett SN. RNA shotgun metagenomic sequencing of Northern California (USA) mosquitoes uncovers viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Front Microbiol. 2015;24;6:185 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbazan P, Thitithanyanont A, Missé D, Dubot A, Bosc P, Luangsri N, et al. Detection of H5N1 avian influenza virus from mosquitoes collected in an infected poultry farm in Thailand. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8(1):105–9. 10.1089/vbz.2007.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbazan P, Palabodeewat S, Nitatpattana N, Gonzalez JP. Detection of host virus-reactive antibodies in blood meals of naturally engorged mosquitoes. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9(1):103–8. 10.1089/vbz.2007.0242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng TF, Willner DL, Lim YW, Schmieder R, Chau B, Nilsson C, Anthony S, Ruan Y, Rohwer F, Breitbart M. Broad surveys of DNA viral diversity obtained through viral metagenomics of mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2011;6(6): e20579 10.1371/journal.pone.0020579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serra OP, Cardoso BF, Ribeiro AL, Santos FA, Slhessarenko RD. Mayaro virus and dengue virus 1 and 4 natural infection in culicids from Cuiabá, state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111(1):20–9. 10.1590/0074-02760150270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.JH Yen. Transovarial transmission of Rickettsia-like microorganisms in mosquitoes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975;266:152–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Socolovschi C, Pages F, Ndiath MO, Ratmanov P, Raoult D. Rickettsia Species in African Anopheles Mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48254 10.1371/journal.pone.0048254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Triebenbach AN, Vogl SJ, Lotspeich-Cole L, Sikes DS, Happ GM, Hueffer K. Detection of Francisella tularensis in Alaskan Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) and Assessment of a Laboratory Model for Transmission. J Med Entomol. 2010;47(4):639–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halouzka J. Borreliae in Aedes vexans and hibernating Culex pipiens molestus mosquitoes. Biologia (Bratisl.) 1993;48:123–124. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halouzka J, Postic D, Hubálek Z. Isolation of the spirochaete Borrelia afzelii from the mosquito Aedes vexans in the Czech Republic. Med Vet Entomol. 1998;12(1):103–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter R, Mendis KN. Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(4):564–94. 10.1128/CMR.15.4.564-594.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bejon P, Williams TN, Liljander A, Noor AM, Wambua J, Ogada E, et al. Stable and unstable malaria hotspots in longitudinal cohort studies in Kenya. PLoS Med. 2010;6;7(7):e1000304 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kangoye DT, Noor A, Midega J, Mwongeli J, Mkabili D, Mogeni P, Kerubo C, Akoo P, Mwangangi J, Drakeley C, Marsh K, Bejon P, Njuguna P. Malaria hotspots defined by clinical malaria, asymptomatic carriage, PCR and vector numbers in a low transmission area on the Kenyan Coast. Malar J. 2016;14;15:213 10.1186/s12936-016-1260-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bousema T, Stresman G, Baidjoe AY, Bradley J, Knight P, Stone W, Osoti V, Makori E, Owaga C, Odongo W, China P, Shagari S, Doumbo OK, Sauerwein RW, Kariuki S, Drakeley C, Stevenson J, Cox J. The Impact of Hotspot-Targeted Interventions on Malaria Transmission in Rachuonyo South District in the Western Kenyan Highlands: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2016;12;13(4):e1001993 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almeida ACG, Kuehn A, Castro AJM, Vítor-Silva S, Figueiredo EFG, Brasil LW, et al. High proportions of asymptomatic and submicroscopic Plasmodium vivax infections in a peri-urban area of low transmission in the Brazilian Amazon. Parasites Vect. 2018;11:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins-Campos KM, Kuehn A, Almeida A, Duarte APM, Sampaio VS, Rodriguez ÍC, da Silva SGM, et al. Infection of Anopheles aquasalis from symptomatic and asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax infections in Manaus, western Brazilian Amazon. Parasit Vectors. 2018;4;11(1):288 10.1186/s13071-018-2749-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Basic Malaria Microscopy Pt.1 Learner's guide Geneva: WHO Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saúde, Ministério da Saúde. Guia prático de tratamento da malária no Brasil. Brasília: Secretaria de Vigilância em and 2015., 2010.http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/guia_pratico_malaria.pdf. Accessed 15 June.

- 32.Wampfler R, Mwingira F, Javati S, Robinson L, Betuela I, Siba P, et al. Strategies for detection of Plasmodium species gametocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76316 10.1371/journal.pone.0076316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosanas-Urgell A, Mueller D, Betuela I, Barnadas C, Iga J, Zimmerman PA, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods for the detection and quantification of the four sympatric Plasmodium species in field samples from Papua New Guinea. Malar J. 2010;9:361 10.1186/1475-2875-9-361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Consoli R, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Principais mosquitos de importância sanitária no Brasil Rio de Janeiro: Editora FIOCRUZ, 1994. 228 p. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faran ME, Linthicum LK. A handbook of the Amazonian species of Anopheles Nyssorhynchus (Diptera: Culicidae). Mosquito Systematics. 13th ed. 1981. p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbosa MGV, Fé NF, Marcião AHR, Silva APT, Monteiro WM, Guerra MV, et al. [Record of epidemiologically important Culicidae in the rural area of Manaus, Amazonas]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41(6):658–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerberg EJ. Manual for mosquito rearing and experimental techniques. Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1979;5:1–124. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pimenta PF, Orfano AS, Bahia AC, Duarte AP, Ríos-Velásquez CM, Melo FF, et al. An overview of malaria transmission from the perspective of Amazon Anopheles vectors. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(1):23–47. 10.1590/0074-02760140266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musapa M, Kumwenda T, Mkulama M, Chishimba S, Norris DE, Thuma PE, et al. A simple Chelex protocol for DNA extraction from Anopheles spp. J Vis Exp. 2013;9(71): 3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruz RMB, Gil LHS, de Almeida e Silva A, da Silva Araújo M, Katsuragawa TH. Mosquito abundance and behavior in the influence area of the hydroelectric complex on the Madeira River, Western Amazon, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(11):1174–6. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gama RA, Silva IM da, Monteiro HAO, Eiras ÁE. Fauna of Culicidae in rural areas of Porto Velho and the first record of Mansonia (Mansonia) flaveola (Coquillet, 1906), for the state of Rondônia, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45(1):125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein TA, Lima JBP, Tang AT. Seasonal distribution and diel biting patterns of culicine mosquitoes in Costa Marques, Rondonia, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1992;87(1):141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luz S, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Forest culicinae mosquitoes in the environs of samuel hydroeletric plant, state of Rondônia, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1996;91(4):427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hutchings RSG, Hutchings RW, Sallum MAM. Culicidae (Diptera, Culicomorpha) from the western Brazilian Amazon: Juami-Japurá Ecological Station. Rev Bras Entomol 2010;54(4):687–91. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muturi EJ, Muriu S, Shililu J, Mwangangi JM, Jacob BG, Mbogo C, Githure J, Novak RJ. Blood feeding patterns of Culex quinquefasciatus and other culicines and implications for disease transmission in Mwea rice scheme, Kenya. Parasitol Res. 2008;102(6):1329–35. 10.1007/s00436-008-0914-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elizondo-Quiroga A, Flores-Suarez A, Elizondo-Quiroga D, Ponce-Garcia G, Blitvich BJ, Contreras-Cordero JF, Gonzalez-Rojas JI et al. Host-feeding preference of Culex quinquefasciatus in Monterrey, northeastern Mexico. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2006;22(4):654–61. 10.2987/8756-971X(2006)22[654:HPOCQI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molaei G, Andreadis TG, Armstrong PM, Bueno R Jr, Dennett JA, Real SV, Sargent C, Bala A et al. Host feeding pattern of Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) and its role in transmission of West Nile virus in Harris County, Texas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(1):73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beier JC, Odago WO, Onyango FK, Asiago CM, Koech DK, Roberts CR. Relative abundance and blood feeding behavior of nocturnally active culicine mosquitoes in western Kenya. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1990;6(2):207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomes AC, Forattini OP. Abrigos de mosquitos Culex (Culex) em zonas rural (Diptera: Culicidae). Rev Saude Publica. 1990;24(5):394–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolfarth BR, Filizola N, Tadei WP, Durieux L. Epidemiological analysis of malaria and its relationships with hydrological variables in four municipalities of the State of Amazonas. Brazil. Hydrol Sci J. 2013;58:1495–504. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forattini OP, Gomes Ade C, Natal D, Kakitani I, Marucci D. Preferências alimentares de mosquitos Culicidae no Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo, Brasil. Rev Saude Publica. 1987;21(3):171–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forattini OP, Gomes Ade C, Natal D, Kakitani I, Marucci D. Frequência domiciliar e endofilia de mosquitos Culicidae no Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo. Rev Saude Publica. 1987;21(3):188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y, Garver LS, Bingham KM, Hang J, Jochim RC, Davidson SA, Richardson JH, Jarman RG. Feasibility of Using the Mosquito Blood Meal for Rapid and Efficient Human and Animal Virus Surveillance and Discovery. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(6):1377–82. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fauver JR, Gendernalik A, Weger-Lucarelli J, Grubaugh ND, Brackney DE, Foy BD, et al. The Use of Xenosurveillance to Detect Human Bacteria, Parasites, and Viruses in Mosquito Bloodmeals. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2017:97(2):324–329. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knöckel J, Molina-Cruz A, Fischer E, Muratova O, Haile A, Barillas-Mury C, Miller LH. An impossible journey? The development of Plasmodium falciparum NF54 in Culex quinquefasciatus. PLoS One. 2013;3;8(5):e63387 10.1371/journal.pone.0063387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imwong M, Nguyen TN, Tripura R, Peto TJ, Lee SJ, Lwin KM, et al. The epidemiology of subclinical malaria infections in South-East Asia: findings from cross-sectional surveys in Thailand-Myanmar border areas, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Malar J. 2015;14:381 10.1186/s12936-015-0906-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vallejo AF, Chaparro PE, Benavides Y, Álvarez Á, Quintero JP, Padilla J, et al. High prevalence of sub-microscopic infections in Colombia. Malar J. 2015;14:201 10.1186/s12936-015-0711-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.