Abstract

Background

Mutations in KRAS are frequent in human cancer, yet effective targeted therapeutics for these cancers are still lacking. Attempts to drug the MEK kinases downstream of KRAS have had limited success in clinical trials. Understanding the specific genomic vulnerabilities of KRAS-driven cancers may uncover novel patient-tailored treatment options.

Methods

We first searched for synthetic lethal (SL) genetic interactions with mutant RAS in yeast with the ultimate aim to identify novel cancer-specific targets for therapy. Our method used selective ploidy ablation, which enables replication of cancer-specific gene expression changes in the yeast gene disruption library. Second, we used a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic screen in KRAS mutant human colon cancer cells to understand the mechanistic connection between the synthetic lethal interaction discovered in yeast and downstream RAS signaling in human cells.

Results

We identify loss of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress sensor IRE1 as synthetic lethal with activated RAS mutants in yeast. In KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cell lines, genetic ablation of the human ortholog of IRE1, ERN1, does not affect growth but sensitizes to MEK inhibition. However, an ERN1 kinase inhibitor failed to show synergy with MEK inhibition, suggesting that a non-kinase function of ERN1 confers MEK inhibitor resistance. To investigate how ERN1 modulates MEK inhibitor responses, we performed genetic screens in ERN1 knockout KRAS mutant colon cancer cells to identify genes whose inactivation confers resistance to MEK inhibition. This genetic screen identified multiple negative regulators of JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) /JUN signaling. Consistently, compounds targeting JNK/MAPK8 or TAK1/MAP3K7, which relay signals from ERN1 to JUN, display synergy with MEK inhibition.

Conclusions

We identify the ERN1-JNK-JUN pathway as a novel regulator of MEK inhibitor response in KRAS mutant colon cancer. The notion that multiple signaling pathways can activate JUN may explain why KRAS mutant tumor cells are traditionally seen as highly refractory to MEK inhibitor therapy. Our findings emphasize the need for the development of new therapeutics targeting JUN activating kinases, TAK1 and JNK, to sensitize KRAS mutant cancer cells to MEK inhibitors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13073-018-0600-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ire1, ERN1, MEK inhibitor, Colon cancer, JNK, JUN

Background

Mutation of specific codons in one of the three RAS genes HRAS, KRAS, or NRAS converts these genes into oncogenes. These mutations are found in a wide variety of tumors, with very high incidences (> 50%) in pancreas and colon cancers [1]. Despite decades of research, generation of selective inhibitors of mutant RAS has proven to be difficult. Recently, allosteric inhibitors of KRAS G12C have been developed [2, 3], but the clinical effectiveness of these compounds remains to be established.

RAS genes are highly conserved in evolution. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two RAS genes: RAS1 and RAS2. These two genes are individually not required for cell viability. However, the double deletion mutant is inviable, indicating that the genes share an essential function [4]. A yeast ras1Δ ras2Δ deletion mutant can be rescued by ectopic expression of a human RAS gene [5]. Vice versa, mutating codon 19 into a valine converts yeast RAS into a constitutively active protein and this mutant yeast RAS can induce malignant transformation of mouse fibroblasts [6].

We searched for synthetic lethal (SL) genetic interactions with mutant RAS in yeast to identify novel cancer-specific targets for therapy. Our method uses selective ploidy ablation (SPA) and allows us to mimic cancer-specific gene expression changes in each of the 4800 nonessential deletion mutant strains in the yeast gene disruption library [7]. Using this approach, we found that inhibition of yeast unfolded protein response (UPR) genes is synthetic lethal with mutant RAS.

The UPR in yeast is mediated by Ire1 and Hac1 [8]. Ire1 is an endonuclease that upon endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress splices HAC1 mRNA. Hac1 is a transcription factor that executes the UPR by activating genes involved in ER homeostasis. The UPR, and the mechanism of activation by splicing of a specific mRNA, is conserved from yeast to humans. Mammalian cells have an IRE1 ortholog named ERN1. Likewise, HAC1 has a functional human homolog, XBP1 [9]. In mammalian KRAS mutant colon cancer, we find that inhibition of MEK kinases is synthetic lethal with inhibition of the UPR. Our findings establish an unexpected link between MEK kinase signaling and the UPR executor ERN1 in human cancer.

Methods

Yeast screen

Wild-type RAS alleles were cloned into pWJ1512 using the A and B adaptamers [10]. Primers to obtain mutant RAS alleles (mutant sequence underlined) were RAS1(V19)-pWJ1512-F 5′ gaattccagctgaccaccATGCAGGGAAATAAATCAACTATAAGAGAGTATAAGATAGTAGTTGTCGGTGGAGTAGGCGTTGGTAAATCTGCTTTAAC, RAS2(V19)-pWJ1512-F 5′ gaattccagctgaccaccATGCCTTTGAACAAGTCGAACATAAGAGAGTACAAGCTAGTCGTCGTTGGTGGTGTTGGTGTTGGTAAATCTGCTTTG, pWJ1512-R 5′ gatccccgggaattgccatg.

The SPA protocol [7] was used to transfer plasmids into the arrayed gene disruption library [11]. Briefly, SPA is a yeast mating-based protocol that allows transfer of a plasmid from a special donor strain into a recipient strain followed by destabilization and counter-selection of the donor yeast chromosomes. The method was adapted for the RAS screen by adding 2% raffinose in addition to 2% galactose as a carbon source for the last two selection steps. In addition, selection steps for RAS2(V19) cells were 1 day longer because overall growth is slower in these strains.

Cell culture, transfection and lentiviral infection

HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM. All other cell lines were maintained in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), STR profiled (by Eurofins Medigenomix Forensik GmbH, Ebersberg, Germany), and routinely tested negative for mycoplasma.

Transfection of HEK293 cells with linear polyethylenimine (PEI) 25K from Polysciences (cat# 23966-2) and subsequent infection of target cells was done as described previously [12]. For knockout of individual genes, the following single-guide (sg) RNAs were cloned in the lentiCRISPR version 2.1 (LC2.1) vector by Gibson cloning: sgERN1-A, 5′-ACATCCCGAGACACGGTGGT-3′; sgERN1-B, 5′-GATGGCAGCCTGTATACGCT-3′; sgDET1, 5′-ACGTGCAGCAGTGTCGCATA-3′; sgCOP1, 5′-AAGCTCCTTCTCCATCACAC-3′. Non-targeting (NT) sgRNA 5′-ACGGAGGCTAAGCGTCGCAA-3′ was used as a control.

Cell proliferation assays and growth curves

For long-term cell proliferation assays, cells were seeded in six-well plates at densities ranging from 1 to 2 × 104 cells per well and cultured with or without inhibitors, as indicated. When control cells reached confluency, all cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (in water).

Live cell growth was measured by automated determination of confluency every 4 h using IncuCyte Zoom (Essen Bioscience). Between 600 and 800 cells were plated per well of a 96-well plate, and experiments were carried out in triplicates.

MEK inhibitors selumetinib (AZD6244) and trametinib (GSK1120212) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals and kept as 10 mM stock solutions in DMSO. ERN1 inhibitor (compound 18) and JNK inhibitor SR-3306 were kindly provided by Astex Pharmaceuticals. TAK1 inhibitor was purchased from Merck as (5Z)-7-Oxozeaenol (CAS 66018-38-0).

Protein lysate preparation and western blot analysis

Cells were lysed and western blots performed as described previously [12]. Primary antibodies against HSP90 (sc-13119), p-JUN (sc-822), and ERK2 (sc-154) were purchased from Santa Cruz. Antibodies against ERN1 (#3294), GAPDH (#5174), p-ERK1/2 (#9101), and JUN (#9165) were from Cell Signaling. Antibodies against COP1 (Genentech, 28A4) and DET1 (Genentech, 3G5) were a gift from Vishva Dixit, Genentech. Secondary antibodies were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories.

Total RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated and purified using Quick-RNA™ MiniPrep (Zymo Research), and reverse transcription was performed with Maxima Universal First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #K1661).

The 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System from Applied Biosystems was used to measure mRNA levels, which were normalized to the expression of GAPDH, in triplicates. The following primer sequences were used in the SYBR® Green master mix (Roche): GAPDH-Fw, AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAA; GAPDH-Rev, AATGAAGGGGTCATTGATGG; ERN1-Fw, AGCAAGCTGACGCCCACTCTG; ERN1-Rev, TGGGGCCCTTCCAGCAAAGGA; CD59-Fw, CAGTGCTACAACTGTCCTAACC; CD59-Rev, TGAGACACGCATCAAAATCAGAT; JUN-Fw, AACAGGTGGCACAGCTTAAAC; JUN-Rev, CAACTGCTGCGTTAGCATGAG; JNK1-Fw, TGTGTGGAATCAAGCACCTTC; JNK1-Rev, AGGCGTCATCATAAAACTCGTTC; JNK2-Fw, GAAACTAAGCCGTCCTTTTCAGA; JNK2-Rev, TCCAGCTCCATGTGAATAACCT. To detect human XBP1 mRNA, we used hXBP1-Fw, GAAGCCAAGGGGAATGAAGT and hXBP1-Rev, GCTGGCAGGCTCTGGGGAAG. To detect human spliced Xbp1, hXBP1-Rev was used with hXBP1spl-Fw, TGCTGAGTCCGCAGCAGGTG, as designed previously [13].

CRISPR-Cas9 resistance screen

To generate ERN1 knockout cells that would not contain the same tracer sequence as currently available CRISPR libraries and thus be suitable for subsequent genome-wide screening, we used a dual vector doxycycline-inducible CRISPR/Cas9 system made on the basis of FH1tUTG [14], as previously described [15]. Single-cell clones were tested for ERN1 knockout by western blot and by measuring the levels of spliced XBP1 using quantitative RT-PCR as described above.

Version 2 of the human genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (GeCKO) half-library A—consisting of 65,383 sgRNAs in lentiviral vectors [16] (Addgene #1000000048)—was used to infect LoVo ERN1 knockout cells with a transduction efficiency of 20% in a sufficient cell number to achieve a 180-fold library coverage. After 48 h, cells were replated and viral supernatant was replaced by medium containing puromycin (2 μg/ml) to select for infected cells for 2 days. After additional 4 days of growth, cells were harvested, a T0 sample was taken, and the rest of the cells were reseeded and cultured in the presence or absence of MEK inhibitors selumetinib and trametinib, in two biological replicates each, for 4 weeks. Genome-integrated sgRNA sequences were PCR amplified and their respective abundance was determined as described previously [17]. The abundance of each sgRNA in the treated versus untreated pools was determined by massively parallel sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. Statistical analysis was performed using DESeq version 1.24.0. The hit selection was based on the overlap between selumetinib and trametinib screens for the genes for which at least one of the sgRNAs meet the following criteria: (A) log2 fold change (of treated over untreated samples) ≥ 7, (B) baseMeanA (mean number of reads in the untreated sample) ≥ 50, and (C) adjusted p value ≤ 0.1. The results overview of the CRISPR screen can be found in Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6.

Results

RAS synthetic lethality screens in yeast

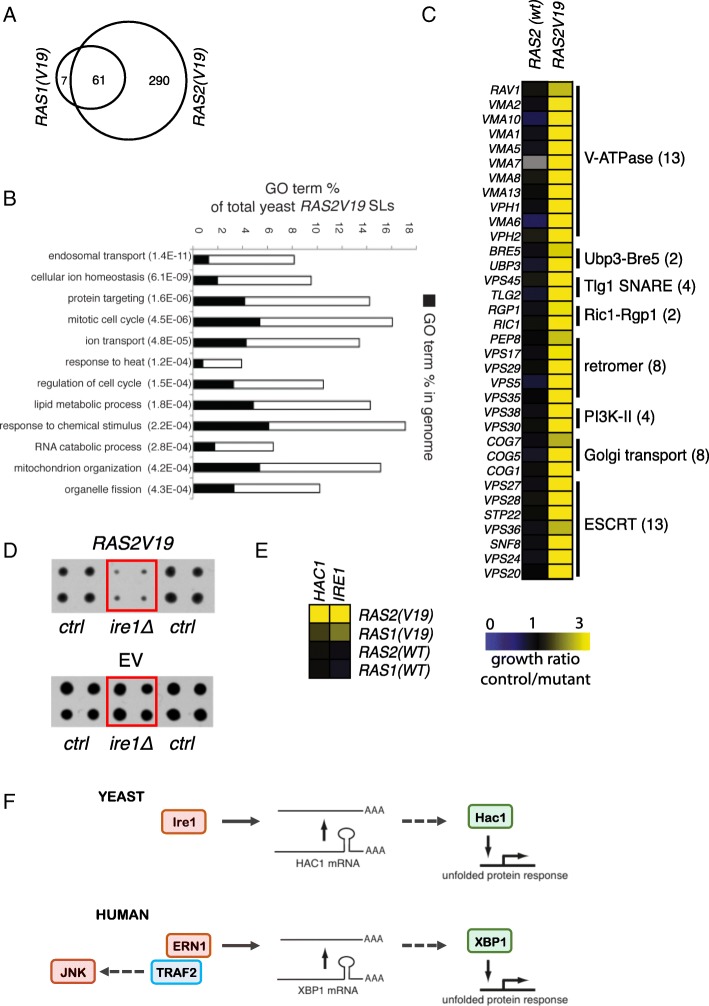

To discover genetic interactions with mutant yeast RAS, we expressed the constitutively active RAS alleles, RAS1(V19), and RAS2(V19), in the collection of ~ 4800 yeast strains in which each individual nonessential gene is deleted [11]. To discriminate between effects due to ectopic expression of the RAS alleles and those due to the specific RAS gene mutations, we also screened the wild-type RAS1(wt) and RAS2(wt) alleles. Additionally, we screened cells harboring an empty vector as a control. Median-normalized growth values were used to calculate the growth ratios between experimental and vector control colonies (Additional file 2: Figure S1A) [18]. We have shown previously that a screen organizes related genes based on phenotype, and these genes exhibit a high density of interactions within the group. The CLIK algorithm plots this density of interactions from the ranked screen results to determine a cutoff for the screen [19]. CLIK analysis of the RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19) screens yielded respectively 151 and 450 strains with a growth defect, which corresponds to a twofold difference in growth compared to the population median in both screens (Additional file 1: Table S1). Although no CLIK groups were identified for the RAS1(wt) and RAS2(wt) screens, the same twofold growth difference cutoff was applied, which yields 14 affected strains from each screen (Additional file 2: Figure S1B-E) indicating that the majority of SL interactions are specific to the activated RAS mutants. Interestingly, most SLs from the RAS1(V19) were also found in the RAS2(V19) screen (Additional file 2: Figure S1F). The growth effects in the RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19) screens were highly correlated although the effect was more severe in the RAS2(V19) screen (Additional file 2: Figure S1G). This finding suggests that the yeast RAS genes form a quantitative redundant pair [20].

To validate the deletion mutants from the SL screens, the strains that showed an SL interaction were rescreened with a mutant or wild-type RAS allele. Forty-six percent of the RAS1(V19) and 79% of the RAS2(V19) SLs from the primary screen also had a growth defect (> 2 times smaller than control) in the validation screen (Additional file 1: Tables S2-S5). Ninety percent of the validated hits of the RAS1(V19) screen overlapped with the RAS2(V19) screen. The gene deletions from the RAS1(wt) and RAS2(wt) screens did not validate in a second screen, indicating that the SLs are specific to the mutant alleles and that RAS1(V19) interacts with a subset of the RAS2(V19) SLs (Fig. 1a). We decided to focus on the genes from the RAS2 mutant screen due to the higher number of interactions and the higher validation rate. In addition, almost all of the RAS1 mutant gene deletions were also found and validated in the RAS2 screen.

Fig. 1.

Unfolded protein response (UPR) executors are synthetic lethal with mutant RAS in S. cerevisiae. a Venn diagram showing the overlap of the RAS synthetic lethal (SL) gene deletion strains identified in the RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19) genetic screens. b Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the SL gene deletion strains from the RAS2(V19) screen identifies a variety of biological processes, including endosomal transport and protein targeting. c List of genes coding for protein complexes among the validated list of RAS2(V19) SL gene deletion mutants. Higher values correspond to stronger growth arrest in the presence of mutant RAS. The pathways and complexes in which the genes are involved are indicated. d The effect of the deletion of the UPR stress sensor IRE1 (ire1Δ) in RAS2(V19) screen (top) and in the empty vector (EV) control background (bottom). e Control vs mutant growth ratios of the UPR genes IRE1 and HAC1. Higher values correspond to stronger growth arrest in the presence of mutant RAS. f Schematic representation of the evolutionary conserved mechanism of UPR execution in yeast (top) and humans (bottom). Ire1 is responsible for the editing of HAC1 mRNA which produces an active executor of the UPR. ERN1 is the human ortholog of yeast IRE1; XBP1 is a functional human homolog of HAC1

An encouraging sign of the validity of our screen was the recapitulation of the synthetic lethal interaction between RAS2(V19) and SIN4. SIN4 is a component of the mediator transcription complex (MED16), and its interaction with RAS2(V19) has been described before [21]. Additionally, we found that another mediator component, PGD1 (MED3), is synthetic lethal with RAS2(V19).

We performed a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the SLs from the RAS2(V19) screen, which identified a variety of biological processes enriched in this screen, including endosomal transport and protein targeting (Fig. 1b). This finding indicates that cells expressing RAS2(V19) are highly dependent on intracellular protein transport. We further analyzed the validated list of RAS2(V19) SLs by identifying protein complexes from which two or more members were present, based on Benschop et al [22]. Again, in this analysis, we recovered several complexes involved in endosomal transport (Fig. 1c). Based on the dependence of cells expressing RAS2(V19) on intracellular transport, we hypothesized that ER homeostasis was disturbed in these cells, which would be consistent with the work of Leber et al [23]. To test this hypothesis, we compared our list of RAS2(V19) SLs to lists of strains that are sensitive to ER stress agents [24]. We confirmed a significant overlap with strains sensitive to β-mercaptoethanol, DTT, and tunicamycin (P = 3.07E−05, hypergeometric test; Additional file 1: Table S6), suggesting that ER homeostasis is disturbed by RAS2(V19).

Mutant RAS is known to inhibit the production of GPI-anchors at the ER [25]. This inhibition likely contributes to permanent ER stress in cells expressing RAS2(V19). To test this theory, we compared the effect of expressing RAS2(V19) with directly inhibiting GPI-anchor production by analyzing the synthetic lethal genetic interactions of ERI1, a non-essential component of the GPI-GnT enzyme [26]. Again, we found a significant overlap between the RAS2(V19) SLs lists and the list of ERI1 genetic interactions (P = 8.60E−09, hypergeometric test; Additional file 1: Table S7). The strongest negative genetic interaction of ERI1 is with IRE1, an important regulator of the UPR. Additionally, ERI1 shows a strong negative genetic interaction with HAC1, a downstream target of Ire1. The UPR is a signaling route that restores ER homeostasis and ire1Δ and hac1Δ strains are highly sensitive to ER stress agents (Additional file 1: Table S6). Importantly, we found both IRE1 and HAC1 are RAS2(V19) SLs (Fig. 1d, e), indicating that ER homeostasis is disturbed in RAS2(V19) expressing cells and that these cells are dependent on the UPR.

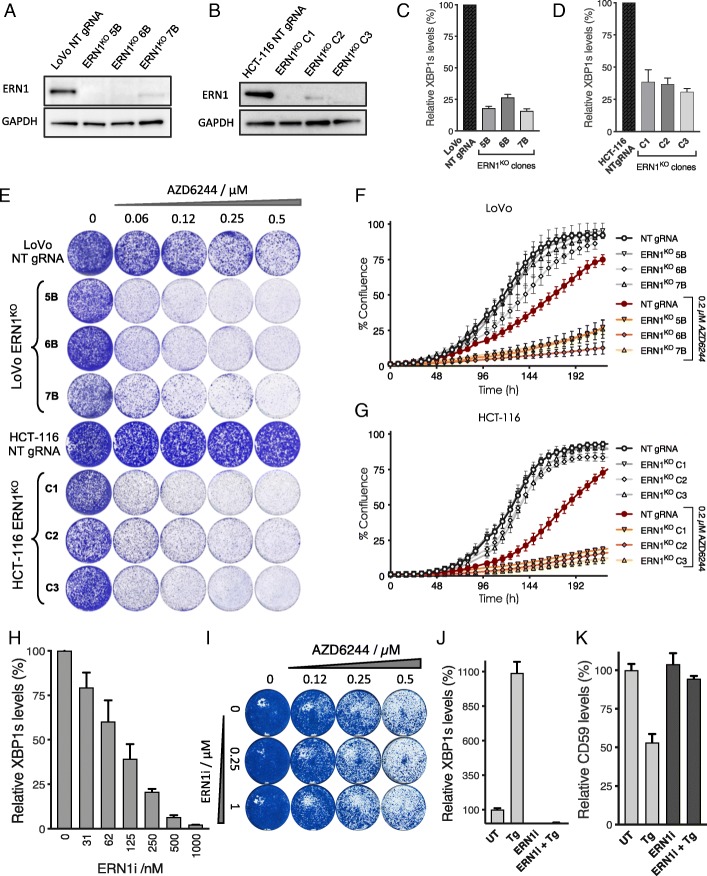

Genetic ablation of ERN1 in KRAS mutant colon cancer cells

The UPR, and the mechanism of activation by splicing of a specific mRNA, is conserved from yeast to humans (Fig. 1f). Mammalian cells have an IRE1 ortholog, named ERN1, while HAC1 has a functional human homolog named XBP1, whose mRNA is spliced by the ERN1 endonuclease domain to form the active, protein-coding XBP1 spliced (XBP1s) form [9]. To test whether ERN1 is essential in cells with active RAS signaling, we created ERN1 knockout (KO) LoVo, HCT-116, SW480, and DLD1 KRAS mutant colon cancer cells using lentiviral CRISPR-Cas9 vectors. ERN1 KO cells had an absence of ERN1 protein and a strong decrease in spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) (Fig. 2a–d). We found that the proliferation of ERN1KO cells was similar to control cells expressing non-targeting (NT) gRNA, indicating that the synthetic lethal interaction between RAS and the UPR is not conserved between yeast and human cells. However, since yeast cells are missing the RAF/MEK/ERK MAPK cascade, we investigated the proliferation of the KRAS mutant ERN1KO cells in the presence of the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244). Interestingly, we found increased MEK inhibitor sensitivity in all ERN1KO LoVo, HCT-116, and SW480 cell clones, both in short-term and in long-term assays (Fig. 2e–g and Additional file 2: Figure S2A-C). In DLD1 cells, no effect on selumetinib response was observed upon ERN1 KO (Additional file 2: Figure S2D-F). These data indicate that a subset of KRAS mutant colon cancer cells can be sensitized to MEK inhibition by loss of ERN1.

Fig. 2.

Effects of ERN1 inhibition in KRAS mutant human colon cancers. a, b Western blot analysis of ERN1 expression in control cells expressing non-targeting (NT) gRNA and LoVo ERN1KO clones 5B, 6B, and 7B (a) and HCT-116 ERN1KO clones C1, C2, and C3 (b). c, d qPCR analysis of spliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1s) in control cells expressing non-targeting (NT) gRNA and LoVo ERN1KO clones 5B, 6B, and 7B (c) and HCT-116 ERN1KO clones C1, C2, and C3 (d). Error bars indicate standard deviation calculated from three biological replicates. e Representative colony formation assays of three different ERN1KO clones compared to the non-targeting (NT) gRNA expressing control cells in the KRAS mutant LoVo (top) and HCT-116 colon cancer cells (bottom). Cells were maintained in the indicated range of concentrations of the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244) for 10 days, stained and photographed. f, g Live cell proliferation assay (IncuCyte®) of control (NT gRNA) and ERN1KO cells following exposure to the MEK inhibitor AZD6244. Error bars indicate standard deviation of three replicate experiments. h qPCR analysis of spliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1s) levels following exposure of LoVo cells to increasing concentrations of the ERN1 kinase inhibitor. Error bars indicate standard deviation calculated from three replicate experiments. i Colony formation assay showing the effect of ERN1 kinase inhibitor on the proliferation of KRAS mutant LoVo cells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244. j Quantification of spliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1s) levels following 1 h treatment with 100 nM of ER stress inducer thapsigargin (Tg) in the presence and absence of the ERN1 kinase inhibitor. k Quantification of the mRNA levels of the RIDD target CD59 after 1 h treatment with 100 nM thapsigargin (Tg) in the presence and absence of the ERN1 kinase inhibitor

Pharmacologic inhibition of ERN1

The ERN1 protein contains both an endonuclease and a kinase domain. A specific inhibitor of ERN1 kinase activity has been developed that results in allosteric inhibition of the endonuclease activity, referred to as compound 18 by Harrington et al [27]. We tested the potency of this inhibitor in LoVo cells by measuring XBP1s levels 24 h after treatment with increasing amounts of ERN1 inhibitor. The compound proved effective with an IC50 of approximately 100 nM (Fig. 2h). Next, we tested whether treatment with this potent ERN1 inhibitor would increase the sensitivity of LoVo cells to the MEK inhibitor. To our surprise, inhibition of ERN1 endonuclease activity was not sufficient to recapitulate the phenotype of the genetic ablation of ERN1 (Fig. 2i).

ERN1 is able to cleave other mRNAs besides XBP1, a process termed regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD) [28]. We tested whether the ERN1 inhibitor interfered with RIDD by stressing LoVo cells with the ER stress-inducing agent thapsigargin (Tg) both in the absence and presence of the ERN1 kinase inhibitor. One of the RIDD targets is CD59 [29]. As expected, XBP1 levels increased and CD59 mRNA levels decreased upon treatment with Tg. In the presence of the ERN1 inhibitor, XBP1 splicing was not increased and CD59 mRNA levels did not decrease upon treatment with Tg (Fig. 2j, k). These data show that RIDD is effectively inhibited by the ERN1 inhibitor and that RIDD targets are unlikely to be involved in the sensitization of ERN1KO cells to the MEK inhibitor.

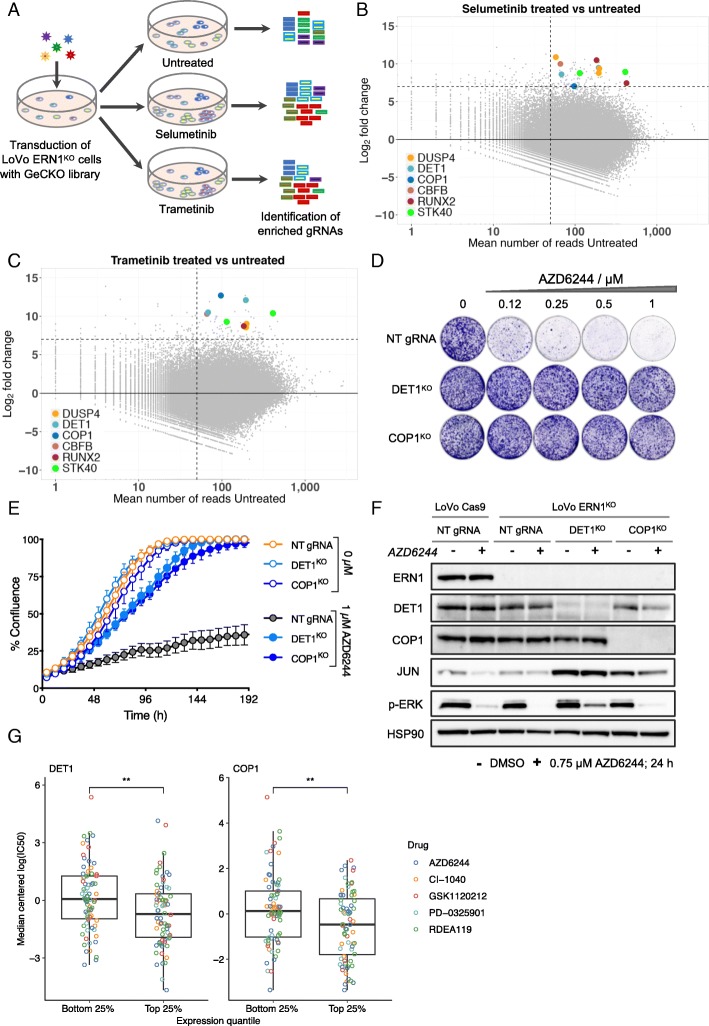

Genome-wide screen reveals ERN1-JNK-JUN signaling axis

To identify a mechanistic link between the ERN1 and the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, we performed a genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 MEK inhibitor resistance screen using ERN1KO LoVo cells. We screened in the presence and absence of two different MEK inhibitors, selumetinib and trametinib (Fig. 3a) and used differential analysis to identify the genes whose knockout confers resistance to MEK inhibitors. Considering that the CRISPR library used contained only three sgRNAs per gene target, we decided not to impose the criterion of multiple sgRNAs per gene. Nevertheless, we found that four hits (DET1, DUSP4, RUNX2 and STK40) were represented by multiple different sgRNAs, while two hits (COP1 and CBFB) each scored with a single sgRNA both in selumetinib and in trametinib screen (Fig. 3b and c). A complete list of screen results can be found in Additional file 1: Tables S8 and S9.

Fig. 3.

A genetic screen for resistance to MEK inhibitors in ERN1 knockout colon cancer. a Schematic outline of the genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screen for resistance to MEK inhibition. Two different MEK inhibitors, selumetinib and trametinib, were used, each in two replicates, and compared to the untreated control population. b, c MA plots of the selumetinib (b) and trametinib screens (c). Horizontal dashed line indicates an arbitrarily imposed threshold of log2 (fold change of treated over untreated) of 7 and vertical dashed line indicates mean number of reads in untreated samples of 50. Highlighted in color are the sgRNAs targeting DUSP4, DET1, COP1, CBFB, RUNX2, and STK40, that are found above these two thresholds (with the p adjusted of ≤ 0.1) in both the selumetinib (b) and the trametinib (c) screen. d, e Functional validation of DET1 and COP1 in LoVo ERN1KO background. d Colony formation assays of DET1 and COP1 KO cells in the presence and absence of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (selumetinib) are shown relative to control cells having NT gRNA. Shown is a representative example of at least three biological replicates. e Live cell proliferation assay of DET1 and COP1 KO cells in the presence and absence of 1 μM AZD6244 compared to control cells expressing NT gRNA. Error bars indicate standard deviation calculated from three replicate experiments. f Western blot analysis of DET1 and COP1 expression in DET1 and COP1 knockout cells using antibodies against ERN1, DET1, COP1, JUN, p-ERK, and HSP90 as control both in the presence and absence of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244. g Median-centered log(IC50) of five different MEK1 inhibitors in high (top 25%) and low (bottom 25%) expressing DET1 (left) and COP1 (right) CRC cell lines in the GDSC100 data set [42]. Cell lines with high DET1 or COP1 expression have significantly lower IC50s (p = 0.004 for both DET1 and COP1). Log(IC50) estimates were median-centered over all cell lines to make them comparable between MEK inhibitors

Dual specificity phosphatase-4 (DUSP4) has been previously implicated in regulating the response to MEK inhibitors, validating the screen performed here [30, 31]. Serine/threonine kinase 40 (STK40) is a negative regulator of NF-κB [32, 33], and NF-κB activity was already shown to directly modulate resistance to several different MAPK pathway inhibitors [34]. In contrast, the remaining four genes (DET1, COP1, CBFB, and RUNX2) have not previously been implicated in MAPK signaling or MEK inhibitor resistance. Interestingly, these four genes code for proteins that act pair-wise in complex with each other. The functional and physical interaction between RUNX2 (also known as core-binding factor subunit alpha-1 or CBFA1), and its transcriptional co-activator CBFB (core-binding factor subunit beta) has been well documented using various in vitro [35] and in vivo model systems [36–39]. DET1 and COP1 are part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that promotes ubiquitination and degradation of the proto-oncogenic transcription factor JUN [40]. Because of a previously established link between ERN1 and JNK [41], we studied DET1 and COP1 further to understand the effects of ERN1 loss on the response to MEK inhibitors.

DET1 and COP1 are regulators of MEK inhibitor response

To validate the results of the genetic screen, we knocked out DET1 and COP1 in ERN1-deficient LoVo cells. Importantly, both in long-term assays (Fig. 3d, and Additional file 2: Figure S3) and in short-term assays (Fig. 3e) loss of either DET1 or COP1 conferred resistance to selumetinib and trametinib in these cells. Both vectors were effective in knocking out their respective targets in a polyclonal knockout cell population (Fig. 3f). In addition, biochemical analysis revealed higher basal JUN levels in DET1- and COP1-negative cell populations, consistent with the fact that DET1 and COP1 are part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that degrades JUN [40]. Moreover, computational analyses of drug response data in a large cancer cell line panel [42] further supports that high DET1 or COP1 expression is correlated with low IC50 values (i.e., sensitivity) for five different MEK inhibitors across a colorectal cancer cell line panel (Fig. 3g).

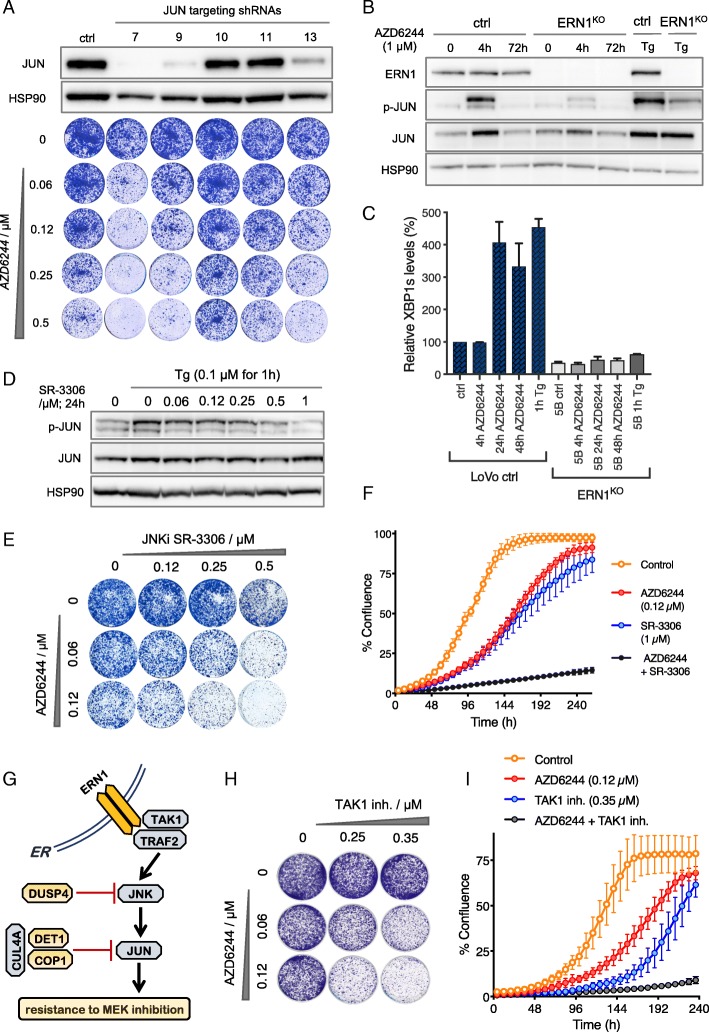

Besides an endonuclease and a kinase function, human ERN1 regulates JNK signaling through binding of the adaptor protein TRAF2 [41], which activates JNK to phosphorylate the transcription factor JUN. We tested if active JNK signaling is important for MEK inhibitor sensitivity by directly knocking down JUN using shRNAs. We found that LoVo cells are dependent on JUN for proliferation upon treatment with MEK inhibitor. Importantly, the sensitivity of the LoVo cells to treatment with MEK inhibitor correlated with the levels of JUN protein (Fig. 4a). To investigate if ERN1 is required for the activation of JUN, we compared JUN phosphorylation in ERN1KO cells to control cells, in the presence and absence of MEK inhibitor. We observed a strong increase in JUN phosphorylation in ERN1 WT cells, compared to ERN1KO cells, after 4 h of MEK inhibitor treatment (Fig. 4b). Consistently, we found that JUN expression is increased by MEK inhibitor in parental cells, but not in ERN1KO cells, which is not caused by expression changes of either JNK1 or JNK2 mRNA (Additional file 2: Figure S4 and S5). These results indicate that ERN1-deficient cells are unable to fully activate JUN signaling, which may explain the MEK inhibitor sensitivity of ERN1KO cells. Moreover, we found that MEK inhibitor treatment induces ERN1 activity, an effect not seen in ERN1KO cells (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Effect of genetic and pharmacologic downregulation of JUN on response to MEK inhibition. a Five different JUN targeting shRNAs were used to downregulate JUN in LoVo cells. JUN protein levels were quantified by western blotting (top), and the response to increasing concentrations of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 on JUN knockdown cells is shown in colony formation assay (bottom). Empty vector infected control (ctrl) cells are shown here for comparison. b Biochemical analysis comparing ERN1KO cells with their control counterparts (ctrl) in the presence and absence of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 for the indicated number of hours. One-hour thapsigargin treatment (Tg) at 0.1 μM was used as a control for p-JUN induction. c Quantification of spliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1s) in the presence and absence of 1 μM AZD6244 at indicated time points. Error bars indicate standard deviation calculated from three replicate experiments. d Biochemical analysis of JUN phosphorylation in the presence and absence of increasing concentrations of the JNK inhibitor SR-3306. One-hour of thapsigargin treatment (Tg) at 0.1 μM was used for p-JUN induction. e A representative colony formation assay of LoVo cells grown in the increasing concentrations of the JNK inhibitor SR-3306 (horizontally) and the increasing concentrations of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (vertically). f Live cell proliferation assay for the combination of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 and the JNK inhibitor SR-3306 (black), each inhibitor individually (red and blue), and vehicle-treated control cells (yellow line). Error bars indicate standard deviation calculated from three replicate experiments. g Schematic representation of the signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) embedded ERN1 to JNK and JUN via its binding factor TRAF2 and TAK1. Shown in yellow are resistance screen hits DUSP4, DET1, and COP1, which are all negative regulators of JNK and JUN, respectively. h A representative colony formation assay showing the effect of the TAK1 inhibitor (5Z)-7-oxozeanol (5ZO) on the proliferation of KRAS mutant LoVo cells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244. i Live cell proliferation assay for the combination of the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 and TAK1 inhibitor 5ZO over the course of 10 days (240 h). Yellow line shows vehicle-treated control cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation calculated from three replicate experiments

Finally, we tested if directly inhibiting JNK kinase signaling with a JNK kinase inhibitor would sensitize LoVo cells to MEK inhibition. The potency and specificity of the JNK inhibitor SR-3306 was tested by measuring phosphorylated JUN levels upon treatment of cells with the ER stress-inducing agent thapsigargin (Tg) (Fig. 4d). We found that LoVo cells were sensitive to the combination of JNK and MEK inhibition (Fig. 4e, f). This effect was also found by blocking TAK1, a kinase upstream of JNK (Fig. 4g–i).

Discussion

Although the yeast and human RAS genes have many properties that are interchangeable, the signaling pathways that are controlled by them differ. Here, we find that both yeast and human RAS share a link with the UPR. The shared interaction suggests that an analogous genetic network structure evolved connecting both yeast and human RAS to the ER stress signaling. Using genome-wide synthetic lethality screens in yeast, we identified multiple genes necessary for ER homeostasis, including the UPR stress sensor IRE1, to be SL with mutant RAS. This genetic interaction was not observed in KRAS mutant colon cancer cells, which are unaffected by genetic ablation of ERN1, the human ortholog of IRE1. However, in contrast to yeast, human cells possess a RAF/MEK/ERK MAPK pathway, and inhibiting this pathway uncovers the SL interaction between ERN1KO and mutant KRAS. Although we conclude that ERN1 itself is dispensable for cell growth and proliferation, we find that its loss can sensitize KRAS mutant colon cancer cells to MEK inhibition. Considering unsatisfactory performance of MEK inhibitors in clinical trials [43–45], we used ERN1 knockout colon cancer cells as a model to study resistance mechanisms to MEK inhibition. As small molecule ERN1 inhibitors failed to enhance sensitivity to MEK inhibition, we resorted to genetic screens to explore the mechanism responsible for the observed synthetic lethality effect. Our genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen identified a series of genetic events that can reinstate MEK inhibitor resistance in ERN1 knockout colon cancer cells. One of the most prominent hits in this screen was dual specificity phosphatase-4 (DUSP4), a well-established tumor suppressor that negatively regulates JUN N-terminal kinase JNK. Upon loss of DUSP4, derepressed JNK activity stimulates JUN-mediated transcription, leading to aberrant MAPK pathway activation [31]. Interestingly, two other screen hits, DET1 and COP1, are also negative regulators of JUN.

Originally described as regulators of light signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana [46], both DET1 (de-etiolated homolog 1) and COP1 (constitutive photomorphogenic 1, also known as RFWD2) mechanistically function as E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases and are evolutionarily conserved members of the COP-DET-FUS protein family. Extensive biochemical studies have shown that COP1-DET1 complex targets JUN for ubiquitination and degradation [40]. Further characterization of in vivo models established the role of human COP1 as a tumor suppressor [47–49]. Here we uncover a role for human COP1 and DET1 in resistance to MEK inhibitors via inhibition of the JNK-JUN pathway.

Since three of the genes identified in our resistance screen (DUSP4, DET1, and COP1) are negative regulators of JUN, we propose that activated ERN1 leads to increased JUN activity, which then translates to cell proliferation despite the inhibition of MEK. ERN1 is linked to the JUN pathway via its binding factor TRAF2, which executes a signaling cascade resulting in the activation of JUN N-terminal kinase JNK [41]. Furthermore, our work demonstrates that the kinase and endonuclease domains of ERN1 are not responsible for the differential sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Recently, we showed that cancers that fail to activate JNK-JUN, due to inactivating mutations in upstream kinases MAP3K1 and MAP2K4, are sensitive to MEK inhibition [50]. Here we demonstrate that ERN1KO cells also fail to activate the JNK-JUN pathway resulting in a similar sensitivity to MEK inhibition.

We propose that the JNK arm of MAPK signaling can functionally compensate for the inhibition of the MEK/ERK signaling axis. Conversely, under conditions of abrogated JNK signaling, such as in the presence of JNK or TAK1 inhibitors, cells become more dependent on the flux of signal through the MEK/ERK pathway. This dependency could then prove to be of therapeutic importance. We speculate that cells in which ERN1 knockout does not sensitize to MEK inhibition (such as DLD1 cells, Additional file 2: Figure S2A-C) can activate JNK-JUN signaling through other pathways, thereby making such cells independent of ERN1 for their MEK inhibitor response. Alternatively, other pathways may be involved in MEK inhibitor resistance in these cells.

We report synergistic cell growth arrest when JNK and MEK inhibitors are combined. Moreover, inhibition of JNK itself (Fig. 4d, e) or JNK activators, such as TAK1 (Fig. 4g, h), might also be useful in preventing intrinsic resistance to MEK inhibitors. In this study, we made use of the resorcyclic lactone (5Z)-7-oxozeanol (5ZO) as a TAK1 inhibitor. However, considerable off-target effects render this molecule inadequate for therapeutic purposes. It remains to be seen whether recently developed TAK1 inhibitors [51] give a more favorable toxicologic profile in the clinic. Taken together, our findings identify an unexpected role for the Unfolded Protein Response executor ERN1 in determining the response to MEK inhibition in KRAS-driven colon cancer.

Conclusions

We identify here a set of genes involved in endosomal transport and ER stress that are synthetic lethal with mutant RAS in yeast. At the crossroads of these processes, we identify IRE1 and HAC1 that are not only synthetic lethal with hyperactivated RAS signaling in yeast, but also with ERI1, a non-essential component of the GPI-GnT enzyme which mediates ER stress response. The fact that IRE1 and HAC1 are both master regulators of the unfolded protein response (UPR) indicates that ER homeostasis is disturbed in mutant RAS expressing cells and that these cells are dependent on the UPR.

Moreover, in human colon cancer cell lines, we find that MAPK pathway shields KRAS mutant cells from synthetic lethality with ERN1, a human ortholog of IRE1. These interactions point to an evolutionarily conserved genetic network structure between RAS signaling and ER stress.

Finally, we find that ERN1 is an important regulator of JUN activity, which becomes crucial for survival in KRAS mutant colon cancer under conditions of abrogated MAPK signaling. We identify the ERN1-JNK-JUN pathway as a novel regulator of MEK inhibitor response in KRAS mutant colon cancer, and point to synthetic lethality of MEK inhibition with therapeutics targeting JUN activating kinases, TAK1 and JNK. The genetic network connecting JUN and MAPK signaling may explain why KRAS mutant tumor cells are traditionally seen as highly refractory to MEK inhibitor therapy, but these genetic interactions may also provide a therapeutically exploitable vulnerability.

Additional files

contains Tables S1-S9. Table S1. Results of the primary yeast screen with RAS alleles RAS1 and RAS2 (wild-type) and mutants RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19). Table S2. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS1. Table S3. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS2. Table S4. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS1(V19). Table S5. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS2(V19). Table S6. Gene deletion yeast strains sensitive to ER stress agents (Y. Chen et al., Mol Cancer Res 2005 [23]) and strains sensitive to the expression of RAS2(V19). Table S7. Gene deletion yeast strains sensitive to ERI1 deletion (M. Costanzo et al., Science 2010 [25]) and strains sensitive to the expression of RAS2(V19). Table S8. Results of the genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen with the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (selumetinib). Table S9. Results of the genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen with the MEK inhibitor trametinib. (XLSX 15504 kb)

Figure S1. Genome-wide synthetic lethal screens with RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19) identify overlapping sets of genes. Figure S2. The response of SW480 ERN1KO and DLD1 ERN1KO KRAS mutant colon cancer cells to MEK inhibition. Figure S3. Colony formation assays of DET1 and COP1 knockout cells (in LoVo ERN1KO background) in the presence and absence of the MEK inhibitor trametinib are shown relative to control cells expressing non-targeting (NT) gRNA. Figure S4. Quantification of JUN expression levels in MEK inhibitor (MEKi, 1 μM AZD6244), JNK inhibitor (JNKi, 1 μM SR-3306) and combination treatment (JNKi + MEKi). One-hour thapsigargin treatment (Tg, 100 nM) was used as a control. Error bars represent standard deviation of three replicate experiments. Figure S5. Quantification of JNK1 (A) and JNK2 (B) expression levels in MEK inhibitor (MEKi, 1 μM AZD6244), JNK inhibitor (JNKi, 1 μM SR-3306) and combination treatment (JNKi + MEKi). One-hour thapsigargin treatment (Tg, 100 nM) was used as a control. Error bars represent standard deviation of three replicate experiments. (PDF 11800 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Bernards, Beijersbergen, Wessels, and Rothstein labs for helpful support and discussions. We acknowledge Samantha Ciccone and Bethany Andresen for their assistance with the yeast screening protocol. We also thank Bastiaan Evers for the initial analysis of the CRISPR screen output and for the dual vector doxycycline-inducible CRISPR/Cas9 system mentioned in the Methods section. We would like to thank Vishva Dixit and Genentech for kindly providing us with DET1 and COP1 antibodies.

Funding

This study was supported by a Rubicon grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grants from the Dutch Cancer Society and the Center for Cancer Genomics. SW was funded in part by research funding from Astex Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, UK) under the Sustaining Innovation Post-Doctoral Programme. R.R. received support from the New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center Health Research Science Board (http://www.wadsworth.org/extramural, HRSB-C028248), the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (R33 CA125520), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35 GM118180). J.D. received support from an NCI training grant (T32 CA009503).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Additional files 1 and 2.

Abbreviations

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- JNKi

JNK inhibitor

- KO

Knockout

- MEKi

MEK inhibitor

- NT

Non-targeting

- PEI

Polyethylenimine

- RIDD

Regulated IRE1-dependent decay

- SL

Synthetic lethal

- SPA

Selective ploidy ablation

- Tg

Thapsigargin

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- WT

Wild-type

Authors’ contributions

TS, SW, and EB generated the data. TS, SW, EB, RJDR, JD, CL, and RLB analyzed the data. TS, SW, RR, LFAW, and RB designed the study. TS, SW, RJDR, and RR wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

RLB is an associate professor at the Division of Molecular Carcinogenesis and the head of High Content Screening Facility at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. LW is a professor of Computational Cancer Biology at the Technical University in Delft and the co-director of the Cancer Systems Biology Center at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. RJDR is a Research Associate in the Department of Genetics & Development at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons. RR is a professor of Genetics & Development and Systems Biology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons. RB is a professor of Molecular Carcinogenesis at the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tonći Šuštić, Email: t.sustic@nki.nl.

Sake van Wageningen, Email: vanwageningen@yahoo.com.

Evert Bosdriesz, Email: e.bosdriesz@nki.nl.

Robert J. D. Reid, Email: rr381@cumc.columbia.edu

John Dittmar, Email: jdittmar@gmail.com.

Cor Lieftink, Email: c.lieftink@nki.nl.

Roderick L. Beijersbergen, Email: r.beijersbergen@nki.nl

Lodewyk F. A. Wessels, Email: l.wessels@nki.nl

Rodney Rothstein, Phone: (212) 305 1733, Email: rothstein@columbia.edu, Email: rjr4@cumc.columbia.edu.

René Bernards, Phone: +31 20 512 1952, Email: r.bernards@nki.nl.

References

- 1.Karnoub AE, Weinberg RA. Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:517–531. doi: 10.1038/nrm2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janes MR, Zhang J, Li L-S, Hansen R, Peters U, Guo X, et al. Targeting KRAS Mutant Cancers with a Covalent G12C-Specific Inhibitor. Cell. 2018;172:578–589.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kataoka T, Powers S, McGill C, Fasano O, Strathern J, Broach J, et al. Genetic analysis of yeast RAS1 and RAS2 genes. Cell. 1984;37:437–445. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kataoka T, Powers S, Cameron S, Fasano O, Goldfarb M, Broach J, et al. Functional homology of mammalian and yeast RAS genes. Cell. 1985;40:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFeo-Jones D, Tatchell K, Robinson LC, Sigal IS, Vass WC, Lowy DR, et al. Mammalian and yeast ras gene products: biological function in their heterologous systems. Science. 1985;228:179–184. doi: 10.1126/science.3883495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid RJD, González-Barrera S, Sunjevaric I, Alvaro D, Ciccone S, Wagner M, et al. Selective ploidy ablation, a high-throughput plasmid transfer protocol, identifies new genes affecting topoisomerase I-induced DNA damage. Genome Res. 2011;21:477–486. doi: 10.1101/gr.109033.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner B. M., Pincus D., Gotthardt K., Gallagher C. M., Walter P. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Sensing in the Unfolded Protein Response. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;5(3):a013169–a013169. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid RJD, Lisby M, Rothstein R. Cloning-free genome alterations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using adaptamer-mediated PCR. Meth Enzymol. 2002;350:258–277. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)50968-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunen D, de Vries RC, Lieftink C, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R. PIM kinases are a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:849–857. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Schadewijk A, van't Wout EFA, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS. A quantitative method for detection of spliced X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) mRNA as a measure of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2012;17:275–279. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0306-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herold MJ, van den Brandt J, Seibler J, Reichardt HM. Inducible and reversible gene silencing by stable integration of an shRNA-encoding lentivirus in transgenic rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18507–18512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806213105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prahallad A, Heynen GJJE, Germano G, Willems SM, Evers B, Vecchione L, et al. PTPN11 is a central node in intrinsic and acquired resistance to targeted Cancer drugs. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1978–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nature Methods. 2014;11:783–784. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evers B, Jastrzebski K, Heijmans JPM, Grernrum W, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R. CRISPR knockout screening outperforms shRNA and CRISPRi in identifying essential genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:631–633. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dittmar JC, Reid RJ, Rothstein R. ScreenMill: a freely available software suite for growth measurement, analysis and visualization of high-throughput screen data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dittmar JC, Pierce S, Rothstein R, Reid RJD. Physical and genetic-interaction density reveals functional organization and informs significance cutoffs in genome-wide screens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7389–7394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219582110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Wageningen S, Kemmeren P, Lijnzaad P, Margaritis T, Benschop JJ, de Castro IJ, et al. Functional overlap and regulatory links shape genetic interactions between signaling pathways. Cell. 2010;143:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard SC, Chang YW, Budovskaya YV, Herman PK. The Ras/PKA signaling pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae exhibits a functional interaction with the Sin4p complex of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Genetics. 2001;159:77–89. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benschop JJ, Brabers N, van Leenen D, Bakker LV, van Deutekom HWM, van Berkum NL, et al. A consensus of core protein complex compositions for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2010;38:916–928. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leber JH, Bernales S, Walter P. IRE1-independent gain control of the unfolded protein response. Steven McKnight, editor. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Feldman DE, Deng C, Brown JA, De Giacomo AF, Gaw AF, et al. Identification of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways that confer resistance to endoplasmic reticulum stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:669–677. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobering AK, Watanabe R, Romeo MJ, Yan BC, Specht CA, Orlean P, et al. Yeast Ras regulates the complex that catalyzes the first step in GPI-anchor biosynthesis at the ER. Cell. 2004;117:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington PE, Biswas K, Malwitz D, Tasker AS, Mohr C, Andrews KL, et al. Unfolded protein response in Cancer: IRE1α inhibition by selective kinase ligands does not impair tumor cell viability. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:68–72. doi: 10.1021/ml500315b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, Weissman JS. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oikawa D, Tokuda M, Iwawaki T. Site-specific cleavage of CD59 mRNA by endoplasmic reticulum-localized ribonuclease, IRE1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balko JM, Cook RS, Vaught DB, Kuba MG, Miller TW, Bhola NE, et al. Profiling of residual breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies DUSP4 deficiency as a mechanism of drug resistance. Nat Med. 2012;18:1052–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balko JM, Schwarz LJ, Bhola NE, Kurupi R, Owens P, Miller TW, et al. Activation of MAPK pathways due to DUSP4 loss promotes cancer stem cell-like phenotypes in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6346–6358. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang J, Teng L, Liu T, Li L, Chen D, Li F, et al. Identification of a novel serine/threonine kinase that inhibits TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation and p53-induced transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:774–778. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu N, Meisgen F, Butler LM, Han G, Wang X-J, Söderberg-Nauclér C, et al. MicroRNA-31 is overexpressed in psoriasis and modulates inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production in keratinocytes via targeting serine/threonine kinase 40. J Immunol. 2013;190:678–688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konieczkowski DJ, Johannessen CM, Abudayyeh O, Kim JW, Cooper ZA, Piris A, et al. A melanoma cell state distinction influences sensitivity to MAPK pathway inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:816–827. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendoza-Villanueva D, Deng W, Lopez-Camacho C, Shore P. The Runx transcriptional co-activator, CBFβ, is essential for invasion of breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:171–111. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kundu M, Javed A, Jeon J-P, Horner A, Shum L, Eckhaus M, et al. Cbfβ interacts with Runx2 and has a critical role in bone development. Nat Genet. 2002;32:639–644. doi: 10.1038/ng1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim K-E, Park N-R, Che X, Han M-S, Jeong J-H, Kim S-Y, et al. Core binding factor β of osteoblasts maintains cortical bone mass via stabilization of Runx2 in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:715–722. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin X, Jiang Q, Matsuo Y, Kawane T, Komori H, Moriishi T, et al. Cbfb regulates bone development by stabilizing Runx family proteins. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:706–714. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komori T. Requisite roles of Runx2 and Cbfb in skeletal development. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;21:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00774-002-0408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wertz IE, O'Rourke KM, Zhang Z, Dornan D, Arnott D, Deshaies RJ, et al. Human De-etiolated-1 regulates c-Jun by assembling a CUL4A ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2004;303:1371–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.1093549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iorio F, Knijnenburg TA, Vis DJ, Bignell GR, Menden MP, Schubert M, et al. A landscape of Pharmacogenomic interactions in Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adjei AA, Cohen RB, Franklin W, Morris C, Wilson D, Molina JR, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2139–2146. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Migliardi G, Sassi F, Torti D, Galimi F, Zanella ER, Buscarino M, et al. Inhibition of MEK and PI3K/mTOR suppresses tumor growth but does not cause tumor regression in patient-derived xenografts of RAS-mutant colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2515–2525. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jänne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR, Jeannin G, Vansteenkiste J, Barrios C, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:38–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei N, Deng XW. Making sense of the COP9 signalosome. A regulatory protein complex conserved from Arabidopsis to human. Trends Genet. 1999;15:98–103. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01670-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Migliorini D, Bogaerts S, Defever D, Vyas R, Denecker G, Radaelli E, et al. Cop1 constitutively regulates c-Jun protein stability and functions as a tumor suppressor in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1329–1343. doi: 10.1172/JCI45784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitari AC, Leong KG, Newton K, Yee C, O'Rourke K, Liu J, et al. COP1 is a tumour suppressor that causes degradation of ETS transcription factors. Nature. 2011;474:403–406. doi: 10.1038/nature10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marine J-C. Spotlight on the role of COP1 in tumorigenesis. Nature Rev Cancer. 2012;12:455–464. doi: 10.1038/nrc3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xue Z, Vis DJ, Bruna A, Sustic T, van Wageningen S, Batra AS, et al. MAP3K1 and MAP2K4 mutations are associated with sensitivity to MEK inhibitors in multiple cancer models. Cell Res. 2018;28:719–729. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0044-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Totzke J, Gurbani D, Raphemot R, Hughes PF, Bodoor K, Carlson DA, et al. Takinib, a Selective TAK1 Inhibitor, Broadens the Therapeutic Efficacy of TNF-α Inhibition for Cancer and Autoimmune Disease. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:1029–1039.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

contains Tables S1-S9. Table S1. Results of the primary yeast screen with RAS alleles RAS1 and RAS2 (wild-type) and mutants RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19). Table S2. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS1. Table S3. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS2. Table S4. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS1(V19). Table S5. Results of the validation yeast screen for RAS2(V19). Table S6. Gene deletion yeast strains sensitive to ER stress agents (Y. Chen et al., Mol Cancer Res 2005 [23]) and strains sensitive to the expression of RAS2(V19). Table S7. Gene deletion yeast strains sensitive to ERI1 deletion (M. Costanzo et al., Science 2010 [25]) and strains sensitive to the expression of RAS2(V19). Table S8. Results of the genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen with the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (selumetinib). Table S9. Results of the genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen with the MEK inhibitor trametinib. (XLSX 15504 kb)

Figure S1. Genome-wide synthetic lethal screens with RAS1(V19) and RAS2(V19) identify overlapping sets of genes. Figure S2. The response of SW480 ERN1KO and DLD1 ERN1KO KRAS mutant colon cancer cells to MEK inhibition. Figure S3. Colony formation assays of DET1 and COP1 knockout cells (in LoVo ERN1KO background) in the presence and absence of the MEK inhibitor trametinib are shown relative to control cells expressing non-targeting (NT) gRNA. Figure S4. Quantification of JUN expression levels in MEK inhibitor (MEKi, 1 μM AZD6244), JNK inhibitor (JNKi, 1 μM SR-3306) and combination treatment (JNKi + MEKi). One-hour thapsigargin treatment (Tg, 100 nM) was used as a control. Error bars represent standard deviation of three replicate experiments. Figure S5. Quantification of JNK1 (A) and JNK2 (B) expression levels in MEK inhibitor (MEKi, 1 μM AZD6244), JNK inhibitor (JNKi, 1 μM SR-3306) and combination treatment (JNKi + MEKi). One-hour thapsigargin treatment (Tg, 100 nM) was used as a control. Error bars represent standard deviation of three replicate experiments. (PDF 11800 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Additional files 1 and 2.