Abstract

Unraveling the dynamic molecular interplay behind complex physiological processes such as neuronal plasticity requires the ability to both detect minute changes in biochemical states in response to physiological signals and track multiple signaling activities simultaneously. Fluorescent protein-based biosensors have enabled the real-time monitoring of dynamic signaling processes within the native context of living cells, yet most commonly used biosensors exhibit poor sensitivity (e.g., dynamic range) and are limited to imaging signaling activities in isolation. Here, we address this challenge by developing a suite of excitation ratiometric kinase activity biosensors that offer the highest reported dynamic range and enable the detection of subtle changes in signaling activity that could not be reliably detected previously, as well as a suite of single-fluorophore biosensors that enable the simultaneous tracking of as many as six distinct signaling activities in single living cells.

INTRODUCTION

Cell function and behavior are shaped by the coordinated actions of multiple biochemical activities. Protein kinases in particular are implicated in regulating nearly all aspects of cellular function through their role as key nodes within intracellular signaling networks. Our understanding of these complex and intricate networks has greatly benefitted from the advent of optical tools, such as genetically encoded biosensors based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), that enable the direct visualization of numerous dynamic biochemical processes, including kinase activity, in living cells. However, fully elucidating how various signaling pathways interact to regulate complex physiological processes, such as neuronal plasticity, requires the ability to move beyond imaging these activities in isolation and has thus fueled a growing interest in the development of strategies to simultaneously track multiple biochemical activities within living cells.

The primary obstacle to such multiplexed imaging is the limited amount of spectral space available to image multiple fluorescent biosensors1. For the most part, current approaches remain largely confined to monitoring two activities in parallel, although four-parameter imaging has been demonstrated by combining spatially separated FRET sensors with a translocating probe and a fluorescent indicator dye2. However, such hybrid strategies cannot be easily adapted to monitoring various activities throughout the cell. Alternatively, single-fluorophore biosensors based on circularly permuted fluorescent proteins (cpFPs) offer a much more straightforward path to image multiple biosensors – and hence, multiple activities – concurrently. Yet while cpFP intensity is known to be modulated by the insertion of conformationally dynamic elements for detecting Ca2+3,4, voltage5, and other small molecules6–8, it remains unclear how easily this sensor design can be generalized for more widespread applications, such as monitoring enzymatic activities. We therefore set out to construct single-fluorophore biosensors for monitoring protein kinase activity. Here, we report a suite of single-fluorophore-based biosensors that enable more sensitive detection of dynamic kinase activities and allow us to reliably monitor multiple signaling activities in living cells, including primary neuronal cultures.

RESULTS

Development and characterization of an excitation ratiometric kinase sensor

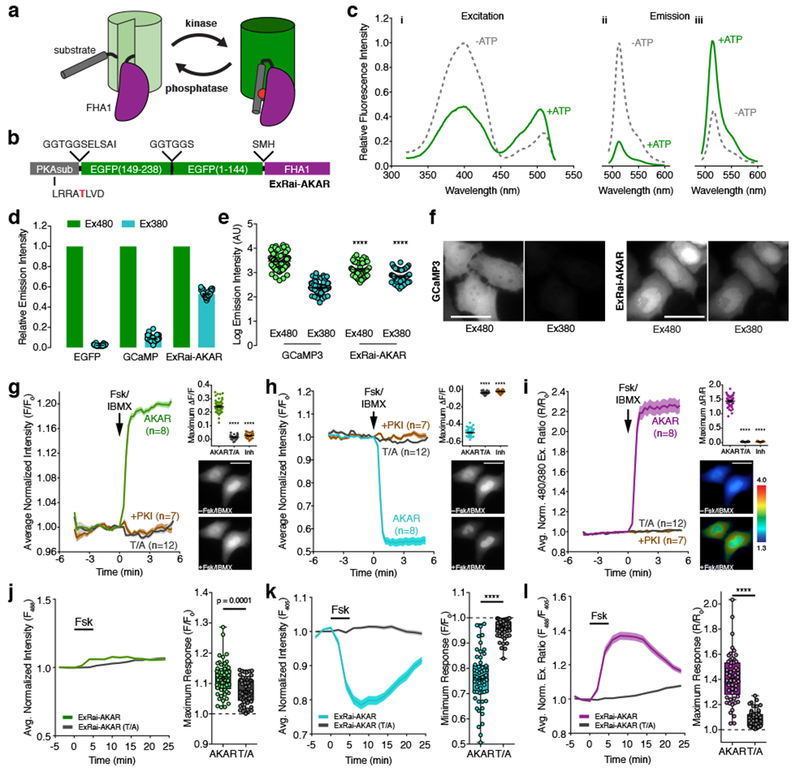

FRET-based kinase activity reporters typically contain a kinase-specific substrate sequence and a phosphoamino acid-binding domain (PAABD, e.g., FHA1) capable of binding the phosphorylated substrate and inducing a FRET change. Based on the hypothesis that this conformational switch could similarly modulate cpFP fluorescence (Fig. 1a), we constructed a prototype single-fluorophore enzyme activity reporter by combining the protein kinase A (PKA) substrate (LRRATLVD) and FHA1 domains of AKAR9 with cpGFP from GCaMP310 (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Design and characterization of ExRai-AKAR.

(a) Modulation of cpFP fluorescence by a phosphorylation-dependent molecular switch. (b) ExRai-AKAR domain structure. (c) Representative ExRai-AKAR fluorescence spectra collected at (i) 530 nm emission and (ii) 380 nm or (iii) 488 nm excitation without (gray) or with (green) ATP in the presence of PKA catalytic subunit. n=3 independent experiments. (d) Relative fluorescence intensities of HeLa cells under 480 nm (Ex480) or 380 nm (Ex380) illumination. n=63 (EGFP), 94 (GCaMP3), and 54 (ExRai-AKAR) cells pooled from 2, 2, and 11 experiments. (e) ExRai-AKAR is dimmer at Ex480 (****p<0.0001, t=5.228, df=136; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test) but brighter at Ex380 (****p<0.0001, t=8.826, df=136; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test) versus GCaMP3. Same n as in (d). (f) Representative GCaMP3 or ExRai-AKAR fluorescence images. (g-i) Average time-courses (left) and maximum (g) Ex480 or (h) Ex380 (ΔF/F), or (i) 480/380 ratio (ΔR/R) responses (right, top) in HeLa cells treated with 50 μM Fsk/100 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX). n=54 (ExRai-AKAR), 36 (ExRai-AKAR[T/A]), and 31 (ExRai-AKAR plus PKI) cells. Time-courses are representative of and maximum responses are pooled from 11, 4, and 4 experiments. ****p<0.0001, F=665.7 (d), F=3956 (e), F=1819 (f); DFn=2, DFd=119; one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s test. Images show ExRai-AKAR (g) Ex480 or (h) Ex380 fluorescence, or (i) 480/380 ratio (pseudocolored) before and after stimulation. Warmer colors indicate higher ratios. Scale bars, 30 μm. (j-l) Average time-courses (left) and maximal (j) 488 nm- or (k) 405 nm-excited fluorescence, or (l) 488/405 ratio responses (right) in the soma of Fsk-treated cultured rat cortical neurons. n=57 (ExRai-AKAR) and 56 (ExRai-AKAR[T/A]) neurons pooled from 5 and 6 experiments. ****p<0.0001, unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test. Curves are normalized to time 0 (g-i) or to the average baseline value (j-l). Solid lines indicate the mean; shaded areas, SEM. Bars in d, e, and g-i represent mean ± SEM. Bar graphs in g-i show box-and-whisker plots indicating the median, interquartile range, min, max, and mean (+). Maximum responses are calculated as ΔF/F=(Fmax-Fmin)/Fmin or ΔR/R=(Rmax-Rmin)/Rmin (g-i) or with respect to time 0 (F/F0 or R/R0; j-k). See Supplementary Table 1 for bar graph source data.

Following bacterial expression and purification, the resulting construct unexpectedly displayed two excitation peaks – a major peak centered around 400 nm and a second, ~4-fold smaller peak at 509 nm with a distinct shoulder at 480 nm – both of which resulted in emission at ~515 nm (Fig. 1c). Both excitation peaks were also similarly sensitive to pH changes between 5.6 and 10 (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results are reminiscent of the neutral and anionic chromophore states found in wild-type Aequorea victoria GFP (wtGFP)11 and, given the absence of any cpGFP mutations, suggest that insertion of the PKAsub and FHA1 domains “rescued” wtGFP chromophore behavior in our construct compared with GCaMP3. In addition, incubation with excess PKA catalytic subunit and ATP led to an ~80% decrease and ~30% increase in the amplitude of the first and second peak, respectively, yielding a >2-fold excitation ratio increase (Fig. 1c). This effect is analogous to the excitation ratiometric behavior observed in several previously described sensors such as ratiometric pericam3, Perceval6, and GEX-GECO112.

When expressed in HeLa cells, the resulting excitation ratiometric (ExRai)-AKAR showed moderate fluorescence at 480 nm, but again showed much stronger fluorescence under 380-nm illumination compared with either EGFP or GCaMP3 (Fig. 1d-f). Furthermore, maximally stimulating PKA in ExRai-AKAR-expressing cells using the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (Fsk) and the pan-phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methyxanthine (IBMX) produced a modest but rapid increase in 480-excited intensity (average change [ΔF/F]: 24.1±0.6%, n=54 [mean ± SEM; n = number of cells]; maximum response: 34.9%) (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 1), a robust decrease in 380-excited intensity (average ΔF/F: −49.7±0.5%, n=54; maximum response: −57.9%) (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 1), and a dramatic increase in the 480/380 excitation ratio (average ΔR/R: 143.7±2.5%, n=54; maximum response: 186.3%) (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 1). A robust ratiometric response was also detected in Fsk-stimulated primary cortical neurons transfected with ExRai-AKAR (Fig. 1j-l). On the other hand, cells expressing a negative-control construct in which the target Thr residue was mutated to Ala (T/A) did not respond to stimulation (Fig. 1g-l), nor did cells co-expressing the potent PKA inhibitor PKI, while acute PKA inhibition reversed the Fsk/IBMX-induced response (Supplementary Fig. 1). These data indicate that ExRai-AKAR dynamically and specifically detects PKA activity in living cells.

Robust detection of compartmentalized PKA activity in response to growth factor stimulation using ExRai-AKAR

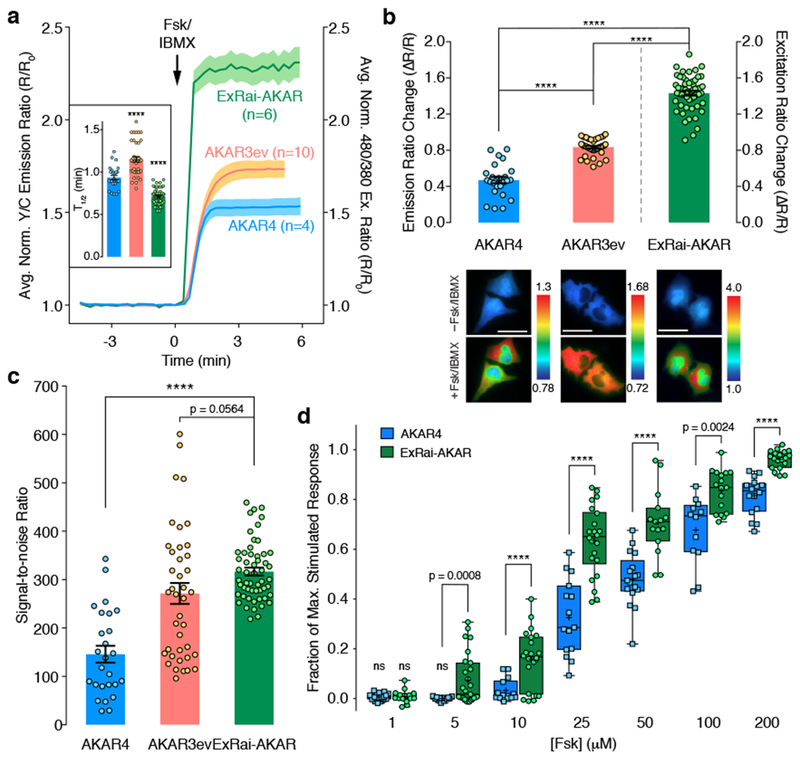

The excitation ratiometric response of ExRai-AKAR represents a substantial improvement in performance compared with existing genetically encoded kinase activity biosensors. For example, when stimulated with Fsk/IBMX, cells expressing ExRai-AKAR exhibited a 3-fold higher dynamic range (143.7±2.5% vs. 47.0±3.5%, p<0.0001) and 2-fold higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR; 316.6±8.3 vs. 145.8±17.4, p<0.0001) compared with AKAR413, as well as a 1.7-fold higher dynamic range compared with the optimized FRET sensor AKAR3ev14 (143.7±2.5% vs. 83.5±1.4%, p<0.0001), with a trend towards higher SNR (316.6±8.3 vs. 271.5±21.6, p=0.0564) (Fig. 2a-c). Meanwhile, dose-response experiments also revealed that ExRai-AKAR responded both more sensitively and more robustly to submaximal PKA stimulation compared with AKAR4 (Fig. 2d), suggesting that ExRai-AKAR can enhance the detection of low-amplitude signaling events.

Figure 2. ExRai-AKAR shows improved performance over previous-generation AKARs.

(a) Time-courses and (b) maximum responses (ΔR/R) in 50 μM Fsk/100 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX)-treated HeLa cells. Inset: Average time to half-maximal response (T1/2)n=26 (AKAR4), 40 (AKAR3ev), and 54 (ExRai-AKAR) cells. Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 4, 6, and 11 experiments. Curves are normalized to time 0 (R/R0). Solid lines represent the mean; shaded areas, SEM. Bars represent mean ± SEM; ****p<0.0001 vs. AKAR4; F=95.57, DFn=2, DFd=104; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. Maximum responses are calculated as ΔR/R=(Rmax-Rmin)/Rmin. Representative ratio images (pseudocolored) before and after Fsk/IBMX treatment are shown below. Warmer colors indicate higher ratios. ****p<0.0001; t=4.537, df=63.99 (AKAR4 vs. AKAR3ev); t=0.39, df=54.81 (ExRai-AKAR vs. AKAR3ev); t=5.926, df=41.12 (ExRai-AKAR vs. AKAR4); unpaired two-tailed Welch’s unequal variance t-test. Scale bars, 30 μm. (c) Signal-to-noise ratio in Fsk/IBMX-treated HeLa cells (see Methods). Bars represent mean ± SEM. n is the same as in (b). ****p<0.0001; t=5.926, df=41.12; unpaired two-tailed Welch’s unequal variance t-test. (d) Dose-response comparison in HeLa cells. Responses are normalized to Fsk/IBMX treatment. Data are shown as box-and-whisker plots showing the median, interquartile range, min, max, and mean (+) . ns, not significantly different from 0; two-tailed one-sample t-test: t=2.041, df=19 (AKAR4, 1 μM; n=20 cells from 3 experiments); t=1.316, df=14 (ExRai-AKAR, 1 μM; n=15 cells from 3 experiments); t=0.2396, df=13 (AKAR4, 5 μM; n=14 cells from 3 experiments). ****p<0.0001; t=3.767, df=26.55 (5 μM; AKAR4, n=14 cells from 3 experiments; ExRai-AKAR, n=27 cells from 7 experiments); t=3.021, df=33.98 (10 μM; AKAR4, n=14 cells from 3 experiments; ExRai-AKAR, n=22 cells from 3 experiments); t=6.299, df=28.21 (25 μM; AKAR4, n=15 cells from 3 experiments; ExRai-AKAR, n=22 cells from 3 experiments); t=5.31, df=27.19 (50 μM; AKAR4, n=17 cells from 3 experiments; ExRai-AKAR, n=15 cells from 3 experiments); t=3.566, df=16.72 (100 μM; AKAR4, n=12 cells from 3 experiments; ExRai-AKAR, n=17 cells from 4 experiments); t=7.073, df=20.73 (200 μM; AKAR4, n=16 cells from 3 experiments; ExRai-AKAR, n=19 cells from 3 experiments); unpaired two-tailed Welch’s unequal variance t-test. See Supplementary Table 1 for bar graph source data.

We examined this further in PC12 cells, where we previously found that nerve growth factor (NGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling yields robust but temporally distinct PKA activity patterns at the plasma membrane, yet fails to elicit cytosolic PKA activity due to the action of cytosolic PDE315. Partial inhibition of PDE3 using milrinone enables both NGF and EGF to weakly stimulate cytosolic PKA activity15, and we found that PC12 cells transfected with cytosol-targeted ExRai-AKAR (ExRai-AKAR-NES; Supplementary Fig. 2) responded much more strongly to co-stimulation with NGF and a submaximal dose of milrinone compared with cells expressing AKAR4-NES (18.8% vs. 2.6%, p<0.0001) (Fig. 3a-c). Thus, ExRai-AKAR greatly enhances our ability to detect subtle changes in PKA activity in living cells.

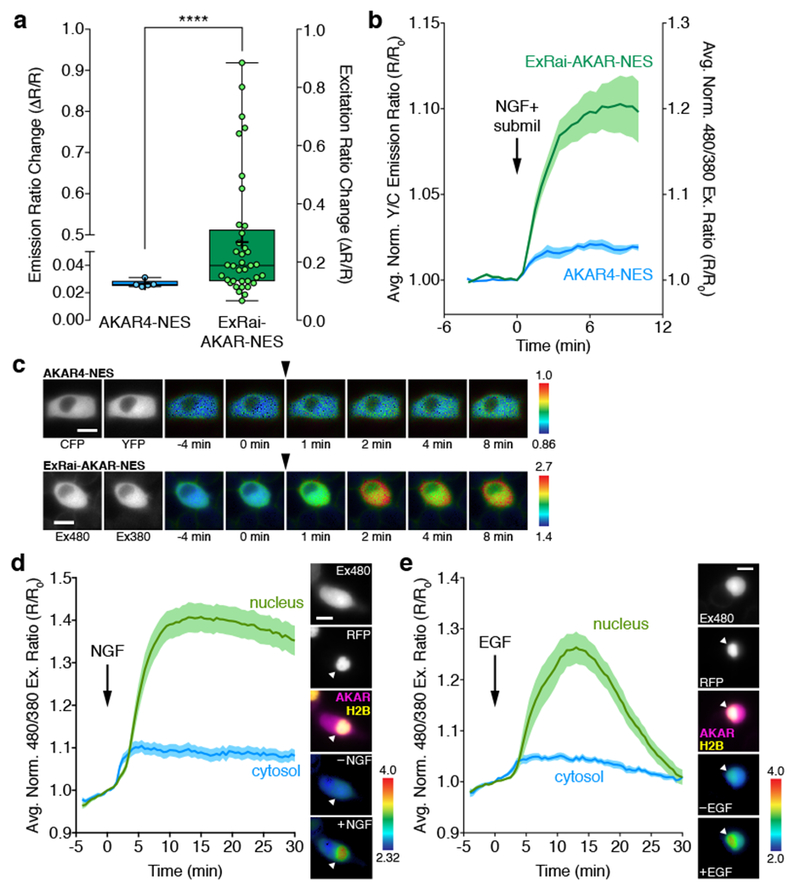

Figure 3. ExRai-AKAR amplifies minute activity changes and reveals compartmentalized PKA signaling in growth factor-stimulated PC12 cells.

(a) Bar graph comparing the maximum responses (ΔR/R) of AKAR4-NES (n=5 cells pooled from 3 experiments) and ExRai-AKAR-NES (n=37 cells pooled from 22 experiments) in PC12 cells treated with 200 ng/mL NGF and a submaximal (5 μM) dose of milrinone (submil). Data are presented as box-and-whisker plots showing the median, interquartile range, min, max, and mean (+). ****p<0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. Ratio changes are calculated as ΔR/R=(Rmax-Rmin)/Rmin. (b) Average time-courses of ExRai-AKAR-NES and AKAR4-NES responses in PC12 cells treated with NGF+submil. Curves are plotted as Y/C emission ratios or 480/380 excitation ratios normalized with respect to time 0 (R/R0). n is the same as in (a). (c) Representative pseudocolor images of the AKAR4-NES (top) and ExRai-AKAR-NES (bottom) ratio responses in PC12 cells treated with NGF+submil. Arrowhead indicates drug addition. Warmer colors indicate higher ratios. Grayscale images (left) show the distribution of probe fluorescence in each channel. (d, e) Left: Average time-courses of the PKA response in the nucleus (green curves) and cytosol (blue curves) in PC12 cells co-expressing diffusible ExRai-AKAR and the nuclear marker histone H2B-mCherry stimulated with (a) 200 ng/mL NGF (n=17 cells pooled from 8 experiments) or (b) 100 ng/mL EGF (n=16 cells pooled from 6 experiments). Curves are plotted as the 480/380 excitation ratio (R/R0) normalized with respect to time 0. Solid lines represent the mean; shaded areas, SEM. Right: representative images showing (from top to bottom) the localization of ExRai-AKAR fluorescence in the 480 nm excitation channel, the localization of mCherry-tagged histone H2B within the nucleus, merged image of ExRai-AKAR (magenta) and H2B (yellow) localization, and pseudocolored images of the ExRai-AKAR excitation ratio before and (a) NGF or (b) EGF stimulation. Warmer colors represent higher ratios. Arrowhead indicates the nucleus. Scale bars in c-e, 10 μm. See Supplementary Table 1 for bar graph source data.

Taking advantage of this increased sensitivity, we then set out to more carefully investigate the spatial compartmentalization of growth factor-stimulated PKA activity in PC12 cells. As expected, cells expressing plasma membrane-targeted ExRai-AKAR (ExRai-AKAR-Kras; Supplementary Fig. 2) exhibited sustained and transient responses to NGF and EGF stimulation, respectively, consistent with our previous observations15 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Surprisingly, however, we also observed rapid and distinct excitation ratio responses in the nuclei of cells expressing diffusible ExRai-AKAR following treatment with either NGF (Fig. 3d) or EGF (Fig. 3e). The nuclear origin of these PKA responses was confirmed by co-localization with mCherry-tagged histone H2B16. Overall, growth factor-induced nuclear PKA dynamics mirrored those observed at the plasma membrane, with NGF-induced responses being largely sustained while EGF induced more transient responses (Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. 2). NGF also appeared to weakly induce cytosolic PKA responses in some cells (10/17; 59%), though this was less apparent for EGF (Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. 2). Given the minimal cytosolic PKA activity, our results suggest growth factor signaling that is initiated at the plasma membrane can be directly coupled to PKA signaling in the nucleus.

Generalizing the design of ExRai-AKAR

A key feature of FRET-based sensors is their modular architecture, which can easily incorporate new domains and is readily generalized for many enzymes. In particular, swapping in various substrate sequences has facilitated the development of a multitude of kinase activity sensors17. To investigate whether the design of ExRai-AKAR could be similarly generalized, we replaced the PKA substrate in ExRai-AKAR with either a PKC18 or Akt/PKB19 substrate (Fig. 4a). The resulting probes functioned as excitation ratiometric sensors for PKC activity and Akt activity when expressed in HeLa and NIH3T3 cells, respectively (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 3). ExRai-CKAR produced a 112.1±4.2% (n=26) increase in the 480/380 excitation ratio (ΔR/R) upon phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stimulation in HeLa cells, with a maximum dynamic range of 156.9% (Fig. 4b). In contrast, HeLa cells expressing an ExRai-CKAR T/A mutant showed no excitation ratio response upon PMA treatment, as did cells pre-treated with the PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (Fig. 4b). Similarly, ExRai-AktAR displayed a 74.9±3.0% (n=13) increase in excitation ratio (ΔR/R), with a maximum response of 93.2%, in NIH3T3 cells treated with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), whereas neither cells expressing ExRai-AktAR (T/A) nor cells pretreated with the Akt inhibitor 10-DEBC responded to PDGF (Fig. 4c). Both ExRai-CKAR and ExRai-AktAR represent the highest-responding biosensor variant for their respective targets.

Figure 4. Construction of ExRai-CKAR and ExRai-AktAR based on a generalized design.

(a) Domain structures of ExRai-CKAR (top) and ExRai-AktAR (bottom). (b) Average time-courses (left) and maximum stimulated responses (ΔR/R, right top) of HeLa cells treated with 100 ng/mL PMA. n=26 (ExRai-CKAR), 17 (ExRai-CKAR[T/A]), and 11 (ExRai-CKAR with PKC inhibitor pretreatment [10 μM Gö6983]) cells. Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 5, 3, and 3 experiments. (****p<0.0001, F=351.9, DFn=2, DFd=51; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparisons test). Representative pseudocolor images show the ExRai-CKAR excitation ratio in HeLa cells before and after stimulation. Warmer colors correspond to higher excitation ratios. (c) Average time-courses (left) and maximum stimulated responses (ΔR/R, right top) of NIH3T3 cells treated with 50 ng/mL PDGF. n=15 (ExRai-AktAR), 16 (ExRai-AktAR[T/A]), and 7 (ExRai-AktAR with Akt inhibitor pretreatment [50 μM10-DEBC]) cells. Curves and bar graphs are pooled from 12, 4, and 5 experiments. (****p<0.0001, F=445.3, DFn=2, DFd=33; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparisons test). Representative pseudocolor images show the ExRai-AktAR excitation ratio in NIH3T3 cells before (middle) and after (bottom) stimulation. Warmer colors correspond to higher excitation ratios. Scale bars, 10 μm. Curves are plotted as 480/380 excitation ratio normalized with respect to time 0 (R/R0). Solid lines represent the mean; shaded areas, SEM. For dot plots in b and c, horizontal bars represent mean ± SEM. Maximum responses are calculated as ΔR/R=(Rmax-Rmin)/Rmin. See Supplementary Table 1 for bar graph source data.

Color-shifting cpFP-based KARs for multiplexed imaging

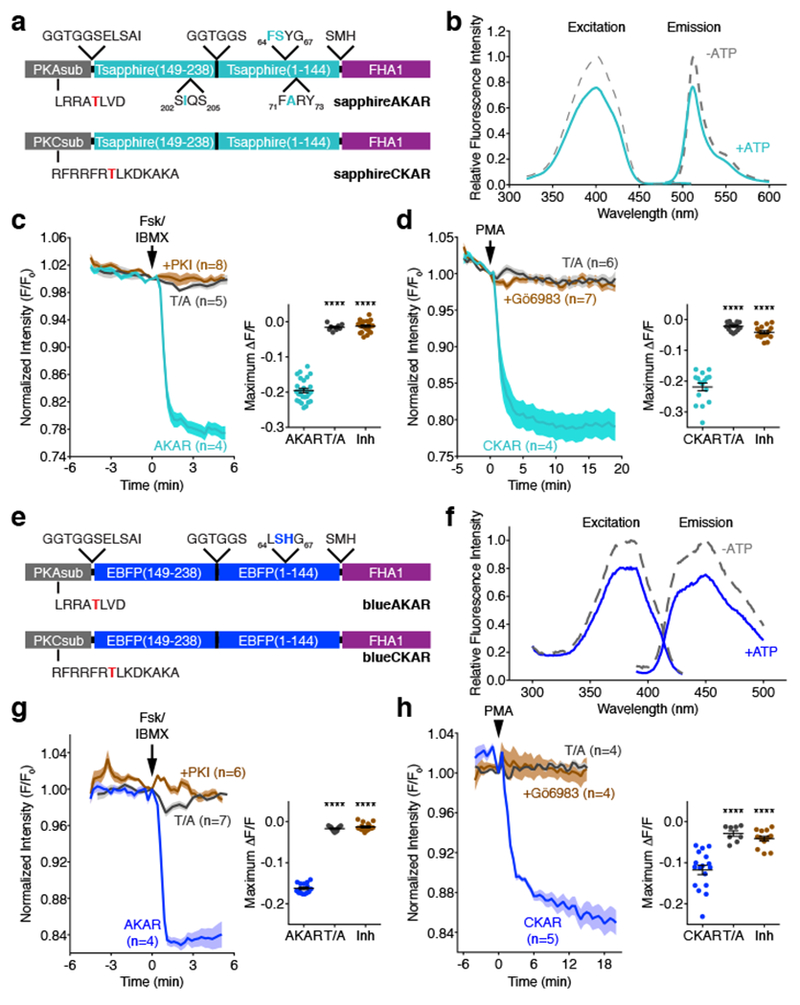

To maximize the spectral space available for multiparameter imaging, single-fluorophore sensors should preferably exhibit single excitation and emission maxima. In addition, for single-fluorophore sensors to succeed as a platform for multiparameter activity imaging, they must also support the incorporation of different FP color variants. Because the ExRai-AKAR excitation spectrum displayed a strong contribution from the neutral GFP chromophore (Fig. 1), we explored the possibility of generating a single-color kinase sensor using circularly permuted T-sapphire, an enhanced long-Stokes-shift GFP variant that lacks the phenolate chromophore species20, by substituting cp-T-sapphire from the redox sensor Peredox21 into our sensor backbone (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5. AKAR and CKAR color variants based on cp-T-sapphire and cpBFP.

(a, e) Domain structures of (a) sapphireAKAR and sapphireCKAR and (e) blueAKAR and blueCKAR. (b, f) Representative fluorescence spectra of (b) sapphireAKAR and (f) blueAKAR collected in without (gray) and with (teal or blue) ATP in the presence of PKA catalytic subunit. n=3 independent experiments. (c) Average time-courses (left) and maximum responses (ΔF/F, right) in Fsk/IBMX-treated HeLa cells. n=27 (sapphireAKAR), 8 (sapphireAKAR[T/A]), and 22 (sapphireAKAR plus PKI) cells. Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 6, 2, and 3 experiments. (****p<0.0001, F=386.4, DFn=2, DFd=54; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparisons test). (d) Average time-courses (left) and maximum responses (ΔF/F, right) in PMA-treated HeLa cells. n=16 (sapphireCKAR), 15 (sapphireCKAR[T/A]), and 16 (sapphireCKAR with 10 μM Gö6983 pretreatment) cells. Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 5, 3, and 3 experiments. (****p<0.0001, F=176.5, DFn=2, DFd=44; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparisons test). (g) Average time-courses (left) and maximum responses (ΔF/F, right) of blueAKAR (n=15 cells), blueAKAR(T/A) (n=11 cells), and blueAKAR plus PKI (n=16 cells) (****p<0.0001, F=1105, DFn=2, DFd=39; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s test). Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 5, 2, and 4 experiments. (f) Average time-courses (left) and maximum responses (ΔF/F, right) of blueCKAR (n=17 cells), blueCKAR(T/A) (n=8 cells), and blueCKAR with Gö6983 pretreatment (n=14 cells) (****p<0.0001, F=26.38, DFn=2, DFd=36; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparisons test). Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 6, 2, and 3 experiments. Curves are normalized with respect to time 0 (F/F0). Solid lines represent the mean; shaded areas, SEM. For dot plots shown in c, d, g, and h, horizontal bars represent mean ± SEM. Maximum responses are calculated as ΔF/F=(Fmax-Fmin)/Fmin. See Supplementary Table 1 for bar graph source data.

As expected, purified recombinant sapphireAKAR exhibited a single excitation and emission maxima at ~400 nm and ~513 nm, respectively, in agreement with the published values for T-sapphire20 (Fig. 5b). Consistent with the behavior of ExRai-AKAR, both peaks also decreased in amplitude when we incubated sapphireAKAR with catalytically active PKA in vitro, though the decrease was smaller (~25%). HeLa cells expressing sapphireAKAR similarly showed a −19.5±0.6% (n=27) change in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F) upon Fsk/IBMX stimulation, with a maximum response of −24.4%, whereas no response was observed in cells expressing sapphireAKAR (T/A) or co-transfected with PKI (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 3). Incorporating a PKC substrate in place of the PKA substrate similarly yielded sapphireCKAR (Fig. 5a), which also displayed a clear decrease in fluorescence intensity in HeLa cells stimulated with PMA (average ΔF/F: −21.9±1.2%, n=16; maximum response: −33.5%) compared with the negative-control sensor or inhibitor pretreatment (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 3).

We then expanded our efforts by incorporating cpBFP from BCaMP, a GCaMP variant that contains BFP chromophore mutations22, into our sensor design (Fig. 5e). Purified blueAKAR displayed single excitation and emission peaks at ~385 nm and ~450 nm, respectively, and much like sapphireAKAR, the amplitude of both peaks decreased upon phosphorylation of the sensor by PKA (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, both blueAKAR and blueCKAR showed clear fluorescence intensity decreases in HeLa cells stimulated with Fsk/IBMX and PMA, respectively (blueAKAR average ΔF/F: −16.2±0.3%, n=15; maximum response: −21.1%; blueCKAR average ΔF/F: −11.8±1.1%, n=16; maximum response: −23.1% (Fig. 5g, h and Supplementary Fig. 3), and no responses were detected in the presence of inhibitor or with negative-control sensors.

An alternative design for red sensors via FP dimerization

Despite these initial successes, we were unable to generate a red-shifted cpFP-based single-color activity sensor, as incorporating cp-mRuby from the red-fluorescent Ca2+ sensor RCaMP22 into our cpFP-AKAR backbone yielded only a dimly fluorescent construct with no meaningful response to PKA stimulation in cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). As an alternative strategy, we utilized dimerization-dependent fluorescent proteins (ddFPs), which are a series of fluorogenic protein pairs comprising a fluorogenic FP-A and a non-fluorescent FP-B, wherein dimerization results in increased FP-A fluorescence intensity23. We previously constructed a red ddFP-based ERK sensor by replacing the CFP/YFP pair of EKARev14 with the RPF-A/B pair (Fig. 6a)24. Although originally utilized in a ratiometric assay based on ddFP exchange, this RAB-EKARev construct also functions as an intensiometric ERK activity reporter. When expressed in HEK293T cells, RAB-EKARev showed a robust, 23.6±0.8% (n=70) increase in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F) upon EGF stimulation, with a maximum increase of 39.7% (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 4). Conversely, cells expressing RAB-EKARev (T/A) showed no response to EGF, nor did cells pretreated with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 6c), while U0126 treatment after EGF stimulation was also able to reverse the RAB-EKARev response (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 6. Generating red-shifted single-fluorophore sensors using ddRFP.

(a) Design and domain structures of the ddRFP-based kinase activity reporters RAB-EKARev and RAB-AKARev. (b) Design and domain structure of the ddRFP-based cAMP reporter RAB-ICUE. (c) Average time-courses (left) and maximum stimulated responses (ΔF/F, right) in HEK293T cells treated with 100 ng/mL EGF. n=70 (RAB-EKARev), 54 (RAB-EKARev[T/A]), and 42 (RAB-EKARev with MEK inhibitor pretreatment [20 μM U0126]) cells. Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 7, 5, and 3 experiments. ****p<0.0001, F=367.7, DFn=2, DFd=163; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s test). (d) Average time-courses (left) and maximum stimulated responses (ΔF/F, right) in HeLa cells treated with 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX). n=19 (RAB-AKARev), 16, 2 (RAB-AKARev[T/A]), and 22 (RAB-AKARev plus PKI) cells. Curves are representative of and bar graphs are pooled from 3, 2, and 2 experiments. ****p<0.0001, F=138.8, DFn=2, DFd=54; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s test). (e) Average time-course of the fluorescence response in HEK293T cells expressing RAB-ICUE after Fsk/IBMX treatment. Data are representative of 4 experiments. Curves are normalized with respect to time 0 (F/F0). Solid lines represent the mean, and shaded areas represent SEM. For dot plots shown in c and d, horizontal bars represent mean ± SEM. Maximum responses are calculated as ΔF/F=(Fmax-Fmin)/Fmin. See Supplementary Table 1 for bar graph source data.

Because the fluorescence intensity increase upon ddFP heterodimer formation broadly parallels the increased FRET between a pair of FPs brought into close proximity by a molecular switch, it should be possible to convert a range of established FRET-based biosensors into intensity-based sensors by replacing the FRET pair with a ddFP pair. We therefore tested the generality of this approach by replacing the FRET pair of AKAR3ev with the RFP-A/B pair (Fig. 6a). As predicted, RAB-AKARev exhibited a 17.2±0.9% (n=19) increase in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F) in HeLa cells treated with Fsk/IBMX, with a maximum response of 26.4% (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, no response was detected in cells expressing RAB-AKARev (T/A) or in cells co-expressing PKI (Fig. 6d). Similarly, incorporating the RFP-A/B pair into the FRET-based cAMP sensor ICUE25 yielded RAB-ICUE (Fig. 6b), which displayed a −20.6±0.8% (n=21) change in RFP fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F) in HEK293T cells treated with Fsk, with a maximum intensity change of −24.5% (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Multiplexed activity imaging in living cells using single-fluorophore biosensors

cAMP/PKA, PKC, and ERK signaling regulate numerous cellular processes and engage in frequent cross-talk, making them ideal candidates for multiplexed imaging studies, and as anticipated, the panel of single-fluorophore biosensors developed above proved apt for this purpose. For example, we were able to simultaneously image PKA, ERK, and PKC activity in HeLa cells co-transfected with blueAKAR, RAB-EKARev, and sapphireCKAR, which exhibited robust and discrete changes in T-sapphire, RFP, and BFP fluorescence intensity upon sequential stimulation using Fsk/IBMX, EGF, and PMA, respectively (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 5). Simultaneous imaging of PKA, cAMP, and PKC responses was also achieved by similarly co-transfecting HeLa cells with blueAKAR, RAB-ICUE, and sapphireCKAR (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 5) or with the alternate combination of sapphireAKAR, RAB-ICUE, and blueCKAR (Supplementary Fig. 5), highlighting the versatility and flexibility of this multiplexed imaging platform. We saw no obvious spectral contamination during co-imaging, though control experiments in cells transfected with individual sensors revealed moderate BFP bleed-through into the T-sapphire channel (Supplementary Fig. 5). Nevertheless, the potential contribution of BFP emission to the recorded T-sapphire intensity was easily removed using standard bleed-through correction (see Methods; Supplementary Fig. 5).

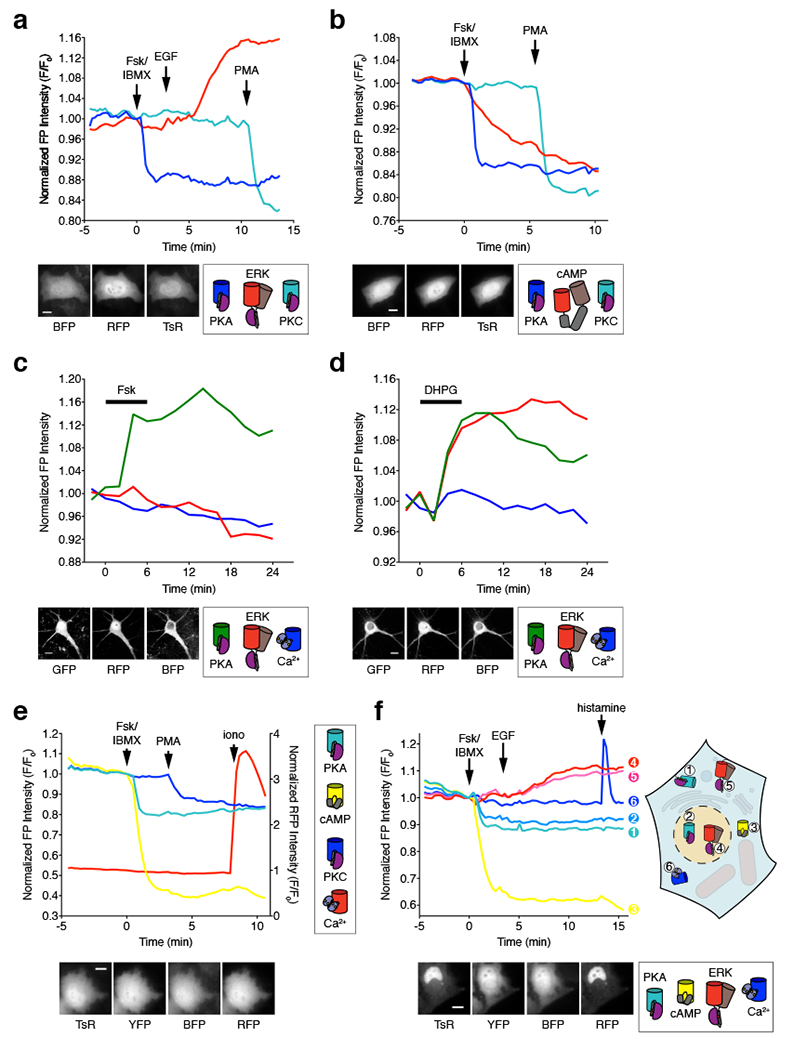

Figure 7. Multiplexed activity imaging using single-fluorophore biosensors.

(a, b) Three-parameter time-lapse epifluorescence imaging in HeLa cells. (a) Time-course of blueAKAR (blue), RAB-EKARev (red), and sapphireCKAR (teal) responses in a single cell treated with 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX), 100 ng/mL EGF, and 100 ng/mL PMA. Data are representative of n=13 cells from 5 independent experiments. Representative images of each channel are shown below. (b) Time-course of blueAKAR (blue), RAB-ICUE (red), and sapphireCKAR (teal) responses in a single cell treated with Fsk/IBMX and PMA. Data are representative of n=17 cells from 3 independent experiments. Representative images of each channel are shown below. (c, d) Three-parameter time-lapse confocal imaging in cultured rat cortical neurons. (c) Time-course of ExRai-AKAR (green; 488 nm excitation), RAB-EKARev (magenta) and BCaMP (blue) responses in the cell soma following Fsk stimulation. Data are representative of n=68 neurons from 6 independent experiments. (d) Time-course of ExRai-AKAR (green; 488 nm excitation), RAB-EKARev (magenta) and BCaMP (blue) responses in the cell soma of a single cultured neuron following DHPG stimulation. Data are representative of n=104 neurons from 10 independent experiments. (e, f) Higher-order multiplexed imaging in HeLa cells. (e) Four-parameter imaging time-course of sapphireAKAR (teal), Flamindo2 (yellow), and blueCKAR (blue), and RCaMP (red) responses in a single cell treated with Fsk/IBMX, PMA, and 1 μM ionomycin (iono). Data are representative of n=15 cells from 8 independent experiments. Representative images of each channel are shown below. (f) Six-parameter imaging time-course in a single cell co-expressing 1) Lyn-sapphireAKAR (teal), 2) sapphireAKAR-NLS (light blue), 3) Flamindo2 (yellow), 4) RAB-EKARev-NLS (red), 5) Lyn-RAB-EKARev (pink), and 6) B-GECO1 (blue) and treated with Fsk/IBMX, EGF, and 100 μM histamine. Data are representative of n=46 cells from 10 independent experiments. Representative images of each channel are shown below. Scale bars, 10 μm. Curves are normalized with respect to time 0 (F/F0; a, b, e, and f) or with respect to the average intensity of the baseline (c, d). Additional curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5–7.

Intracellular signaling pathways also play an important role in the brain during learning and memory, especially during synaptic plasticity, where changes in the activities of kinases such as PKA and ERK interact to induce long-lasting modulation of synaptic strength26. However, the temporal and spatial dynamics of these signaling pathways are not fully understood. Using multiplexed imaging of our single-fluorophore biosensors, we can begin to explore these interactions. Here, we successfully performed three-parameter activity imaging in primary neuronal cultures (Fig. 7c, d and Supplementary Fig. 6). Specifically, we were able to simultaneously monitor changes in PKA and ERK activity, as well as Ca2+ influx, by co-transfecting rat cortical neurons with ExRai-AKAR, RAB-EKARev, and the Ca2+ probe BCaMP, and found that Fsk treatment led to a specific increase in 488 nm-excited ExRai-AKAR intensity (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 6), while application of (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), which is known to activate both PKA and ERK signaling via mGluR1/5, increased the intensity of both ExRai-AKAR (488 nm excitation) and RAB-EKARev (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. 6).

We were also able to easily expand into four-parameter multiplexing by combining our sensors with previously described single-fluorophore probes of different colors. Specifically, we were able to simultaneously monitor changes in PKA and PKC activity, as well as cAMP and Ca2+ elevations, in single cells by co-transfecting sapphireAKAR and blueCKAR into HeLa cells in combination with the yellow cAMP sensor Flamindo28 and the red Ca2+ sensor RCaMP22. Cells expressing all four biosensors displayed robust and specific decreases in T-sapphire and YFP fluorescence intensity upon stimulation with Fsk/IBMX, with subsequent PMA and ionomycin treatment yielding a clear decrease in BFP intensity and increase in RFP intensity, respectively (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Fig. 7). As above, only BFP bleed-through into the T-sapphire channel was detected in control experiments, which was easily corrected (Supplementary Fig. 7). Here, multiplexed imaging of four biochemical activities in living cells was achieved exclusively using spectrally separated biosensors.

Based on these results, we reasoned that even further multiplexing may be achieved by incorporating additional measures such as the physical separation of biosensors via targeting to non-overlapping subcellular structures (e.g., the plasma membrane and nucleus). To test this idea, we first targeted sapphireAKAR and RAB-EKARev to the plasma membrane and nucleus and imaged their responses individually in HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). By applying this targeted sensor approach in conjunction with Flamindo2 and another blue Ca2+ probe, B-GECO112, we were then able to successfully perform 6-fold multiplexing in which we simultaneously monitored membrane- and nuclear-localized PKA and ERK activity alongside cytosolic cAMP and Ca2+ accumulation in single living cells (Fig. 6f). All 6 probes were expressed well when co-transfected into HeLa cells, and each responded selectively to sequential stimulation with Fsk/IBMX, EGF, and histamine (Fig. 7f and Supplementary Fig. 7). A subset of cells (12/46, 26%) also exhibited an EGF-induced Ca2+ transient immediately before the onset of ERK activity (Supplementary Fig. 7). The single-fluorophore biosensors developed here thus represent a powerful platform for dissecting complex signaling networks via highly multiplexed activity imaging in living cells.

DISCUSSION

Subtle shifts in kinase activity are often critical for finely tuning the behavior of important physiological processes, such as the modulation of synaptic plasticity27,28, neuronal activity oscillations29, cardiac myofibril contraction30, and mechano-sensitive signaling31 by PKA. While these minute changes in kinase activity often approach the detection limit of genetically encoded FRET-based biosensors32, our results suggest that such physiologically relevant, subtle changes in kinase activity may be readily detectable using ExRai-KARs. Indeed, ExRai-AKAR not only vastly outperformed the FRET-based AKAR4 probe in reporting small cytosolic PKA activity changes in PC12 cells but also enabled the detection of endogenous, growth factor-stimulated nuclear PKA activity in these cells (Fig. 3). The existence and regulation of nuclear PKA signaling have been a topic of extensive interest33,34. Our findings suggest growth factor signaling can be directly coupled to nuclear PKA signaling, perhaps via regulation of a nuclear pool of PKA holoenzyme34, and further highlight the potential for ExRai-KARs to illuminate hidden aspects of signaling biology. Notably, ExRai-AKAR also appeared to display faster response kinetics than previous AKARs (Fig. 3). Thus, ExRai-AKAR should prove similarly well suited for monitoring small, rapid changes in signaling within cellular subcompartments and nanodomains, such as local PKA activity dynamics in dendritic spines27.

Complex physiological processes such as neuronal synaptic plasticity are also shaped by the convergence of multiple signaling activities26, making highly multiplexed activity imaging essential for unravelling the underlying network dynamics. Yet with few exceptions2,35, two-parameter multiplexing has largely remained the norm36, even with single-fluorophore biosensors37,38, given their relatively narrow target profile. Similarly, although the recent development of enhanced Nano-lantern (eNL) color variants teases the possibility of five-color activity multiplexing39, only eNL-based Ca2+ sensors have been developed to date. In contrast, we successfully utilized ExRai-AKAR as a generalizable backbone to construct a suite of intensiometric single-fluorophore kinase sensors in various colors, with ddRFP serving as an alternative design strategy to obtain red sensors. Using these probes, we successfully performed three- to fourfold multiplexed imaging of different combinations of signaling activities (e.g., PKA/PKC/ERK, PKA/ERK/Ca2+, PKA/cAMP/PKC/Ca2+) in both cultured cell lines and dissociated primary neurons (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figs. 5–7). We were able to extend this approach even further through the supplementary use of biosensor targeting, thereby enabling us to simultaneously monitor activities in different subcellular locations and achieve sixfold activity multiplexing in single living cells (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 7).

In summary, our work presents a versatile and readily usable toolkit for obtaining a deeper understanding of kinase activity dynamics in living cells. Future efforts to expand the color palette (e.g., incorporate red and far-red cpFPs) and improve the dynamic range of these single-fluorophore KARs will further strengthen this already powerful toolkit. Together, these fluorescent biosensors will greatly enhance our ability to unravel the overlapping molecular events underlying complex processes, such as neuronal synaptic plasticity, in their physiological context.

METHODS

Biosensor construction

To construct ExRai-AKAR, cpGFP was PCR amplified from GCaMP310 using the forward primer 5’-GGCAGCGAGCTCAGCGCGATCAACGTCTATATCAAGGCC-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-GTCGACATGCATGCTGTTGTACTCCAGCTTGTGCCCCAG-3’ (SacI and SphI sites underlined), and FHA1 with a stop codon was PCR amplified from plasmid DNA using forward primer 5’-GCCCGCATGCATAAGTTTTCTCAAGAA-3’ and reverse primer 5’-CGGAATTCTTAGCGATCAACTTTGTTC-3’ (SphI and EcoRI sites underlined). The resulting PCR fragments were then ligated into a SacI/EcoRI-digested backbone containing a PKA substrate sequence. Vector backbones containing PKC and Akt substrate sequences were similarly used to generate ExRai-CKAR and ExRai-AktAR, respectively. The original cpGFP sequence in ExRai-AKAR and ExRai-CKAR was then replaced by subcloning with a SacI/SphI-digested PCR fragment encoding either cp-T-sapphire from Peredox21 (forward primer 5’-GGCAGCGAGCTCAGCGCGATCAACGTGTATATCATGGCT-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GTCGACATGCATGCTGTTGTACTCCAGCTTGTGCCCCAG-3’, SacI and SphI sites underlined) or cpBFP from BCaMP22 (forward primer 5’-GGCAGCGAGCTCAGCGCGATCAACGTCTATATCAAGGCC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GTCGACATGCATGCTGTTGTACTCCAGCTTGTGCCCCAG-3’, SacI and SphI sites underlined) to generate sapphireAKAR and sapphireCKAR or blueAKAR and blueCKAR. RAB-AKARev was generated by subcloning a BglII/SacI-digested fragment containing the FHA1 domain, Eevee linker, and PKA substrate sequence from FLINC-AKAR140 and a SacI/EcoRI-digested fragment encoding the ddFP-B sequence into a RAB-EKARev backbone cut with BglII and SacI. RAB-ICUE was generated by subcloning a PCR fragment encoding the conformational switch from ICUE2, corresponding to amino acids 149–881 of Epac125, amplified using forward primer 5’-GGCAGCGCATGCCCCGTGGGAACTCATGAG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GGAGGCGAGCTCTGGCTCCAGCTCTCGGGA-3’ (SphI and SacI sites underlined), between ddRFP-A and ddFP-B via SphI and SacI digestion. Biosensors were constructed in the pRSETB vector (Invitrogen) and then subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) behind a Kozak sequence via BamHI/EcoRI digestion for mammalian expression or into pCAG for neuronal expression. Non-phosphorylatable (T/A) mutant ExRai-AKAR was generated by subcloning a cpGFP-FHA1 fragment into a SacI/EcoRI-digested backbone containing a mutated PKA substrate. ExRai-, sapphire-, and blueCKAR (T/A) (primer 5’-CGATTCAGAAGATTCCAGGCGTTGAAGGACAAGGCTAAG-3’); ExRai-AktAR (T/A) (primer 5’-CCTCGTCCGCGCTCGTGCGCCTGGCCGGACCCCAGGCCG-3’); RAB-EKARev (T/A) (primer 5’-GGACCAGATGTCCCTAGAGCTCCAGTGGATAAAGCAAAG-3’); and RAB-AKARev (T/A) (primer 5’-GGTTCCGGATTGAGGCGCGCGGCCCTGGTTGACGGCGGCAGCGAG-3’) were generated via site-directed mutagenesis. Cytosolic and plasma membrane-targeted ExRai-AKAR, as well as plasma membrane- and nuclear-targeted sapphireAKAR and RAB-EKARev, were generated by subcloning into pcDNA3 backbones containing a C-terminal nuclear export signal (EFLPPLERLTL), the C-terminal targeting sequence from KRas (KKKKKSKTKCVIM), the N-terminal 11 amino acids from Lyn kinase (MGCIKSKRKDK), or a C-terminal nuclear localization signal (PKKKRKVEDA). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Other plasmids

mCherry-tagged PKIα9, AKAR413, AKAR4-NES15, and RAB-EKARev24 were reported previously. PKI-GFP was PCR amplified from p4-PKIg (gift of Dr. Thomas McDonald, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) using forward primer 5’-GAACCAGCTAGCGCCGCCACCAAGCTTATGTATCCATATGACGTCCCAGAC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GGCGAATTCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC-3’ and cloned into pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen) via NheI/EcoRI digestion (sites underlined) to remove the targeting sequence and insert a Kozak sequence and initiation codon. AKAR3ev14 was a gift of Dr. Michiyuki Matsuda (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). GCaMP310, BCaMP, and RCaMP22 were kind gifts of Dr. Loren Looger (Janelia Farm Research Campus, HHMI, Ashburn, VA). Peredox21 was kindly provided by Dr. Gary Yellen (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Flamindo28 was kindly provided by Dr. Tetsuya Kitaguchi (Waseda University, Singapore, Singapore). B-GECO112 was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Campbell (University of Alberta, Canada). H2B-mCherry16 was a gift of Dr. Robert Benezra (Addgene plasmid #20972).

Biosensor purification and in vitro characterization

Polyhistidine-tagged ExRai-AKAR, sapphireAKAR, and blueAKAR in pRSETB (Invitrogen) were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 cells and purified by nickel affinity chromatography. Briefly, cells were grown at 37°C to OD600=0.3–0.4 and then induced overnight at 18°C with 0.4 mM IPTG. The cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl) containing 1 mM PMSF and Complete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), and lysed by sonication. Following centrifugation at 25000 x g for 30 min at 4°C, the clarified lysate was loaded onto an Ni-NTA column, and bound protein was subsequently eluted using an imidazole gradient (10–200 mM). Eluded fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE, pooled, and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal columns (30 kD cut-off, Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a Spark 20M microplate reader (Tecan).

Fluorescence excitation and emission spectra were obtained on a PTI QM-400 fluorometer (Horiba). Excitation scans were collected at 530 nm emission for ExRai-AKAR, 515 nm emission for sapphireAKAR, and 450 nm emission for blueAKAR; emission scans were performed at 380 nm and 488 nm for ExRai-AKAR and at 380 nm for both sapphireAKAR and blueAKAR. Purified biosensors (1 μM) were incubated with 5 μg of PKA catalytic subunit (gift of Dr. Susan S. Taylor, UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA) for 30 min at 30°C in kinase assay buffer (New England Biolabs; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.01% Brij 35) without ATP for dephosphorylated spectra or with 200 μM ATP for phosphorylated spectra. pKa values were determined by measuring the excitation spectra of ExRai-AKAR diluted into buffer (100 mM citric acid/200 mM dibasic sodium phosphate; 50 mM Tris-HCl; 50 mM glycine) with different pH values.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 1 g/L glucose and supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma) and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (Pen-Strep, Sigma-Aldrich). NIH3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) containing 1 g/L glucose and supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% (v/v) Pen-Strep (Sigma-Aldrich). PC12 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) containing 1 g/L glucose and supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Sigma), 5% donor horse serum (DHS, Gibco), and 1% (v/v) Pen-Strep (Sigma-Aldrich). All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Prior to transfection, cells were plated onto sterile 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes and grown to 50–70% confluence. Cells were then transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and grown an additional 24 h (HeLa, HEK293T) or 48 h (PC12) before imaging. NIH3T3 cells were changed to serum-free DMEM immediately prior to transfection and serum-starved for 24 h before imaging. PC12 cells were changed to reduced serum medium (5% FBS, 1% DHS) 24 h prior to imaging. For 6-parameter imaging experiments, HeLa cells with transfected using the calcium-phosphate method.

Cortical neurons obtained from Sprague-Dawley rats at embryonic day 18 were plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated 18-mm glass cover slips in standard 12-well tissue culture dishes at a density of 250,000 cells/well and grown in glia-conditioned neurobasal media supplemented with 2% B-27, 2 mM Glutamax, 50 U/mL PenStrep, and 1% horse serum. Cultured neurons were fed twice per week. At 12–13 days in vitro, cortical neurons were transfected with kinase sensors and GFP or dsRed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Time-lapse fluorescence imaging

Epifluorescence imaging

Cells were washed twice with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS, Gibco) and subsequently imaged in HBSS in the dark at 37°C. Forskolin (Fsk; Calbiochem), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; Sigma), nerve growth factor (NGF; Harlan Laboratories), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; LC Laboratories), Gö6983 (Sigma), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF; Sigma-Aldrich), 10-DEBC (Tocris), epidermal growth factor (EGF; Sigma-Aldrich), U0126 (Sigma-Aldrich), ionomycin (iono; Calbiochem), and histamine (Sigma-Aldrich) were added as indicated. For 6-parameter imaging experiments, cells were washed and imaged in Ca2+-free HBSS. Images were acquired on a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 40x/1.3 NA objective and a Photometrics Evolve 512 EMCCD (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) controlled by METAFLUOR 7.7 software (Molecular Devices). Dual GFP excitation ratio imaging was performed using a 480DF30 excitation filter and 505DRLP dichroic mirror, a 380DF10 excitation filter and 450DRLP dichroic mirror, and a 535DF45 emission filter; T-sapphire intensity was imaged using a 380DF10 excitation filter, a 450DRLP dichroic mirror, and a 535DF45 emission filter; BFP intensity was imaged using a 380DF10 excitation filter, a 450DRLP dichroic mirror, and a 475DF40 emission filter; RFP intensity was imaged using a 568DF55 excitation filter, a 600DRLP dichroic mirror, and a 653DF95 emission filter; and YFP intensity was imaged using a 495DF40 excitation filter, a 515DRLP dichroic mirror, and a 535DF25 emission filter. Dual cyan/yellow emission ratio imaging was performed using a 420DF20 excitation filter, a 450DRLP dichroic mirror, and two emission filters (475DF40 for CFP and 535DF25 for YFP). All filter sets were alternated by a Lambda 10–2 filter-changer (Sutter Instruments). Exposure times ranged between 50 and 500 ms, with EM gain set from 10–50, and images were acquired every 15–30 s.

Raw fluorescence images were corrected by subtracting the background fluorescence intensity of a cell-free region from the emission intensities of biosensor-expressing cells. GFP excitation ratios (F480/F380) or yellow/cyan emission ratios were then calculated at each time point. The resulting time-courses were normalized by dividing the ratio or intensity at each time point by the basal value at time zero (e.g., F/F0 or R/R0), which was defined as the time point immediately preceding drug addition. Maximum intensity (ΔF/F) or ratio (ΔR/R) changes were calculated as (Fmax-Fmin)/Fmin or (Rmax-Rmin)/Rmin, where Fmax and Fmin or Rmax and Rmin are the maximum and minimum intensity or ratio value recorded after stimulation, respectively. Signal-to-noise ratios in Figure 2 were calculated from single-cell ratio time-courses by dividing the maximum stimulated ratio change by the standard deviation of the baseline before drug addition. Graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software).

Fluorescence bleed-through correction

To assess potential bleed-through of fluorescence intensity in the multi-parameter imaging experiments, cells were individually transfected with each single-fluorophore biosensor and then imaged under the same conditions used during multi-parameter imaging. For these experiments, obvious bleed-through was only detected in the T-sapphire channel in cells expressing BFP (e.g., blueAKAR or blueCKAR). Bleed-through correction factors were determined by first plotting the pixel intensity of the T-sapphire channel versus that of the BFP channel and then extracting the slope from a linear fit of the resulting XY scatter in MATLAB (MathWorks). Corrected T-sapphire intensities were calculated as ITsR’=ITsR–(C•IBFP), where ITsR’ and ITsR are the corrected and uncorrected T-sapphire intensity, respectively, IBFP is the BFP intensity, and C is the correction factor. To avoid possible over-correction, bleed-through correction was only applied to cells with ITsR<1000 and ITsR/IBFP<2.

Confocal imaging of cortical neurons

Two days after transfection, neurons were imaged on a Zeiss spinning-disk confocal microscope using a 40x/1.6 NA oil objective. Neurons were mounted on a heated, custom-built perfusion chamber and continuously perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 30 mM D-glucose, and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) warmed to 37°C. Images were acquired every 2 min, and at least 3 baseline images were acquired before stimulation with either 10 μM Fsk or 100 μM DHPG for 6 min followed by washout with ACSF for 15 min. Neurons were pre-incubated in 37°C ACSF for 60 min before mounting on the microscope. For DHPG stimulation experiments, ACSF used during pre-incubation, baseline, and washout was supplemented with 100 μM (2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV). At the end of each experiment, neurons were stimulated with 10–50 μM KCl to test for general excitability. For image analysis, background-subtracted intensity values of the cell soma were normalized to the average intensity during baseline. Maximal intensity or ratio changes were calculated with respect to the initial value at time 0 (e.g., F/F0 or R/R0). Only neurons with stable baseline intensities were included in the analysis. Image analysis and quantification was performed using ImageJ.

Code availability

No custom computer code was used in the present study.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software). All data were tested using the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. For Gaussian data, pairwise comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test or Welch’s unequal variance t-test, and comparisons between three or more groups were performed using ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. Non-Gaussian data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test for pairwise comparisons or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for analyses of three or more groups. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Unless otherwise noted, experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. Average time-courses shown in Fig. 1 g-h, 2a, 4b, 5, and 6 depict individual representative experiments. Average time-courses shown in Fig. 3 and 4c depict combined datasets due to the low number of cells per experiment. Average time-courses from cultured rat cortical neurons (Fig. 1j-l, Supplementary Fig. 6a-d) depict combined datasets.

Data availability

Source data for bar graphs shown in Fig. 1–6 and Supplementary Fig. 6 have been provided as Supplementary Table 1. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Loren Looger, Gary Yellen, Michiyuki Matsuda, Tetsuya Kitaguchi, and Robert Campbell for generously providing plasmids and to Susan Taylor for providing purified PKA catalytic subunit. We also wish to thank Eric Greenwald for helping with the bleed-through analysis and correction, as well as Elena Lopez Ortega for helping with subcloning and neuronal imaging experiments. This work was supported by Brain Initiative Grant R01 MH111516 (to R.L.H. and J.Z.) and by R35 CA197622, R01 DK073368, and R01 GM111665 (to J.Z.). Y. Z. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31771125), the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (grant 2017YFE0103400), and The One Thousand Talents Plan-Recruitment Program for Young Professionals.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Depry C, Mehta S & Zhang J Multiplexed visualization of dynamic signaling networks using genetically encoded fluorescent protein-based biosensors. Pflugers Arch 465, 373–381 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piljic A & Schultz C Simultaneous recording of multiple cellular events by FRET. ACS Chem Biol 3, 156–160 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagai T, Sawano A, Park ES & Miyawaki A Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 3197–3202 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakai J, Ohkura M & Imoto K A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 19, 137–141 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang HH et al. Subcellular Imaging of Voltage and Calcium Signals Reveals Neural Processing In Vivo. Cell 166, 245–257 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg J, Hung YP & Yellen G A genetically encoded fluorescent reporter of ATP:ADP ratio. Nat Methods 6, 161–166 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marvin JS et al. An optimized fluorescent probe for visualizing glutamate neurotransmission. Nat Methods 10, 162–170 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odaka H, Arai S, Inoue T & Kitaguchi T Genetically-encoded yellow fluorescent cAMP indicator with an expanded dynamic range for dual-color imaging. PLoS ONE 9, e100252 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Hupfeld CJ, Taylor SS, Olefsky JM & Tsien RY Insulin disrupts beta-adrenergic signalling to protein kinase A in adipocytes. Nature 437, 569–573 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian L et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods 6, 875–881 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsien RY The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 509–544 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca²⁺ indicators. Science 333, 1888–1891 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depry C, Allen MD & Zhang J Visualization of PKA activity in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol Biosyst 7, 52–58 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komatsu N et al. Development of an optimized backbone of FRET biosensors for kinases and GTPases. Mol Biol Cell 22, 4647–4656 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbst KJ, Allen MD & Zhang J Spatiotemporally regulated protein kinase A activity is a critical regulator of growth factor-stimulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in PC12 cells. Mol Cell Biol 31, 4063–4075 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nam H-S & Benezra R High levels of Id1 expression define B1 type adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5, 515–526 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman RH, Fosbrink MD & Zhang J Genetically encodable fluorescent biosensors for tracking signaling dynamics in living cells. Chem Rev 111, 3614–3666 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbst KJ, Allen MD & Zhang J Luminescent kinase activity biosensors based on a versatile bimolecular switch. J Am Chem Soc 133, 5676–5679 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X & Zhang J Spatiotemporal analysis of differential Akt regulation in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol Biol Cell 19, 4366–4373 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zapata-Hommer O & Griesbeck O Efficiently folding and circularly permuted variants of the Sapphire mutant of GFP. BMC Biotechnol. 3, 5 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung YP, Albeck JG, Tantama M & Yellen G Imaging cytosolic NADH-NAD(+) redox state with a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor. Cell Metabolism 14, 545–554 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akerboom J et al. Genetically encoded calcium indicators for multi-color neural activity imaging and combination with optogenetics. Front Mol Neurosci 6, 2 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alford SC, Abdelfattah AS, Ding Y & Campbell RE A fluorogenic red fluorescent protein heterodimer. Chem. Biol. 19, 353–360 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding Y et al. Ratiometric biosensors based on dimerization-dependent fluorescent protein exchange. Nat Methods 12, 195–8– 3 p following 198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Violin JD et al. beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling and desensitization elucidated by quantitative modeling of real time cAMP dynamics. J Biol Chem 283, 2949–2961 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huganir RL & Nicoll RA AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: the last 25 years. Neuron 80, 704–717 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diering GH, Gustina AS & Huganir RL PKA-GluA1 Coupling via AKAP5 Controls AMPA Receptor Phosphorylation and Cell-Surface Targeting during Bidirectional Homeostatic Plasticity. Neuron 84, 790–805 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanderson JL, Gorski JA & Dell’Acqua ML NMDA Receptor-Dependent LTD Requires Transient Synaptic Incorporation of Ca²⁺-Permeable AMPARs Mediated by AKAP150-Anchored PKA and Calcineurin. Neuron 89, 1000–1015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J et al. Multiple Kinases Involved in the Nicotinic Modulation of Gamma Oscillations in the Rat Hippocampal CA3 Area. Front Cell Neurosci 11, 57 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao V et al. PKA phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I modulates activation and relaxation kinetics of ventricular myofibrils. Biophys J 107, 1196–1204 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Z et al. Acute mechanical stretch promotes eNOS activation in venous endothelial cells mainly via PKA and Akt pathways. PLoS ONE 8, e71359 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn TA et al. Imaging of cAMP levels and protein kinase A activity reveals that retinal waves drive oscillations in second-messenger cascades. J Neurosci 26, 12807–12815 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith FD et al. Local protein kinase A action proceeds through intact holoenzymes. Science 356, 1288–1293 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sample V et al. Regulation of nuclear PKA revealed by spatiotemporal manipulation of cyclic AMP. Nat Chem Biol 8, 375–382 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niino Y, Hotta K & Oka K Blue fluorescent cGMP sensor for multiparameter fluorescence imaging. PLoS ONE 5, e9164 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aye-Han N-N & Zhang J A multiparameter live cell imaging approach to monitor cyclic AMP and protein kinase A dynamics in parallel. Methods Mol Biol 1071, 207–215 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harada H et al. Phosphorylation and inactivation of BAD by mitochondria-anchored protein kinase A. Mol Cell 3, 413–422 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tewson P et al. Simultaneous detection of Ca2+ and diacylglycerol signaling in living cells. PLoS ONE 7, e42791 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki K et al. Five colour variants of bright luminescent protein for real-time multicolour bioimaging. Nat Commun 7, 13718 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mo GCH et al. Genetically encoded biosensors for visualizing live-cell biochemical activity at super-resolution. Nat Methods 14, 427–434 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for bar graphs shown in Fig. 1–6 and Supplementary Fig. 6 have been provided as Supplementary Table 1. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.