Abstract

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system. The inflammatory process in MS is driven by both T and B cells and current therapies are targeted to each of these cell types. Epigenetic mechanisms may provide a valuable link between genes and environment. DNA methylation is the best studied epigenetic mechanism and is recognized as a potential contributor to MS risk. The objective of this study was to identify DNA methylation changes associated with MS in CD19+ B-cells. We performed an epigenome-wide association analysis of DNA methylation in the CD19+ B-cells from 24 patients with relapsing-remitting MS on various treatments and 24 healthy controls using Illumina 450 K arrays. A large differentially methylated region (DMR) was observed at the lymphotoxin alpha (LTA) locus. This region was hypermethylated and contains 19 differentially methylated positions (DMPs) spanning 860 bp, all of which are located within the transcriptional start site. We also observed smaller DMRs at 4 MS-associated genes: SLC44A2, LTBR, CARD11 and CXCR5. These preliminary findings suggest that B-cell specific DNA-methylation may be associated with MS risk or response to therapy, specifically at the LTA locus. Development of B-cell specific epigenetic therapies is an attractive new avenue of research in MS treatment. Further studies are now required to validate these findings and understand their functional significance.

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis is an inflammatory and neurogenerative disease leading to demyelination and axonal loss. Risk of developing MS is thought to be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. The primary environmental factors that influence disease pathology are sunlight exposure, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and smoking1. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 149 genes associated with MS risk with approximately one third coming from variations in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)2,3. Despite this, there still remains a large element of unexplained heritability in terms of disease pathology.

Epigenetic mechanisms are capable of modifying the genome without changes to the DNA sequence and can be inherited. One well-studied epigenetic mechanism is DNA methylation, which is the addition of a methyl group to CpG dinucleotides. We, and others, have used genome-wide DNA methylation technologies to identify differentially methylated positions (DMPs) in the T-cells of MS patients compared to healthy controls4–8. In two independent studies of CD4+ T-cells, we found a striking differentially methylated region (DMR) located within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region, with a major peak at HLA-DRB1 and RNF394,6. Using the same cohort of patients we assessed DMPs in CD8+ T-cells and found 79 DMPs, all of which showed minor association with MS but none of which overlapped with any of the DMPs found in CD4+ T-cells5. A study by Bos et al. also found little overlap between the methylation profiles of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, highlighting the importance of investigating individual cell subtypes.

There is evidence to suggest that T-cells may have a role in MS pathology (reviewed in Martin et al.9). However, it is becoming increasingly clear that B-cells may also play a substantial role in helping to drive disease. Activated B-cells may contribute to MS pathology as antibody producing cells, antigen presenting cells or as a source of pro-inflammatory cytokines (reviewed in Lehmann-Horn et al.10). Evidence for this is in the success of B-cell depleting monoclonal antibodies, such as rituximab11 and ocrelizumab12 as MS therapies. Additionally, many currently approved MS therapies, for example fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate, also have an impact on B cells through reduced numbers or a shift in phenotype towards a more anti-inflammatory cytokine profile (reviewed in Lehmann-Horn et al.10).

In an effort to identify B-cell specific DMPs associated in MS, we performed genome-wide DNA methylation study of CD19+ B-cells from MS patients and healthy controls. We used the same cohort and data analysis techniques as our previous studies so that the results could be compared to those from the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells.

Methods and Materials

Ethics Statement

The Hunter New England Health Research Ethics Committee and University of Newcastle Ethics committee approved this study (05/04/13.09 and H-505-0607 respectively), and methods were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines on human subject experiments. Written and informed consent was obtained from all patient and control subjects. MS patients gave written and verbal consent. The Australian Red Cross Blood Service ethics committee approved the use of blood from healthy donors.

Sample Processing

We performed an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of CD19+ B-cells using the same patient cohort, work flow and data analysis as described in our previous study4. Briefly, whole blood was collected from 24 RRMS patients and 24 healthy controls. All patients were diagnosed with RRMS according to the McDonald criteria13. PBMCs were isolated from 45 mL of whole blood by density gradient centrifugation on lymphoprep (StemCell Technologies, Canada). CD19+ B cells were isolated using positive selection, magnetic separation kits (Stem Cell Technologies, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Purity was assessed using FITC conjugated anti-CD19 antibody (clone H1B19, catalog #60005FL.1, StemCell Technologies, Canada) and the FACS CantoII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) and analyzed using the FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, USA). All samples met a minimum purity threshold of ≥90%. DNA was extracted using the QiaAMP DNA micro kit (Qiagen, USA). DNA was then bisulphite converted and hybridized to Illumina 450 K arrays (service provided by the Australian Genome Research Facility).

Data analysis

Raw fluorescence data were processed using a combination of R/Bioconductor and custom scripts. Raw data was parsed into the Bioconductor MINFI package. Methylation data was background corrected and quantile normalized according to MINFI routines. Data was cleaned by removing control probes, probes which map multiple times to the genome, cross-reactive probes and failed probes for which the intensity of both the methylated and the unmethylated probes was <1000 units across all samples. A threshold of 1000 units was selected based on the profile of the available negative control probes. Y chromosome probes were filtered out. All probe sequences were mapped to the human genome (buildHg19) using BOWTIE14 to identify potential hybridization anomalies. We chose to retain probes containing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and filter these out post hoc where appropriate (see results section).

Measures of methylation (β values) were produced for each probe and ranged from completely unmethylated (β = 0) to completely methylated (β = 1). To identify differentially methylated positions (DMPs) associated with MS subtypes in this cohort, we first calculated the difference in median β value by subtracting the median β value of controls (mediancont) from the median β value for cases (mediancase). This produced a Δmeth score ranging from −1 (hypomethylated) to 1 (hypermethylated). A two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (K-S test) was used to determine if Δmeth was statistically significant. A K-S test was chosen over the F test because of the marked variation in the distribution of the β values among the probes. Rather than base our CpG selection strictly on statistical significance (P-values) of the K-S test, which is overly limiting due to the small sample size and could miss important signal, we used a selection strategy based on a combination of P-value and effect size (ie. Δmeth score). We have used this approach successfully in previous studies to implicate differential methylation at HLA in CD4+ cells with regard to MS4–6. A CpG was considered a DMP if the P-value was <0.05 and the absolute β value was >±0.1. Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were called if at least two DMPs were found within a 500 base pair (bp) span of each other and were altered in the same direction (either all hypermethylated or all hypomethylated).

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA): To assess the biological relevance of DMPs in terms of MS pathology we conducted an ORA on resultant the DMP list using the WebGestalt engine (www.webgestalt.org) incorporating the KEGG pathways database.

Results

DMP and DMR analyses

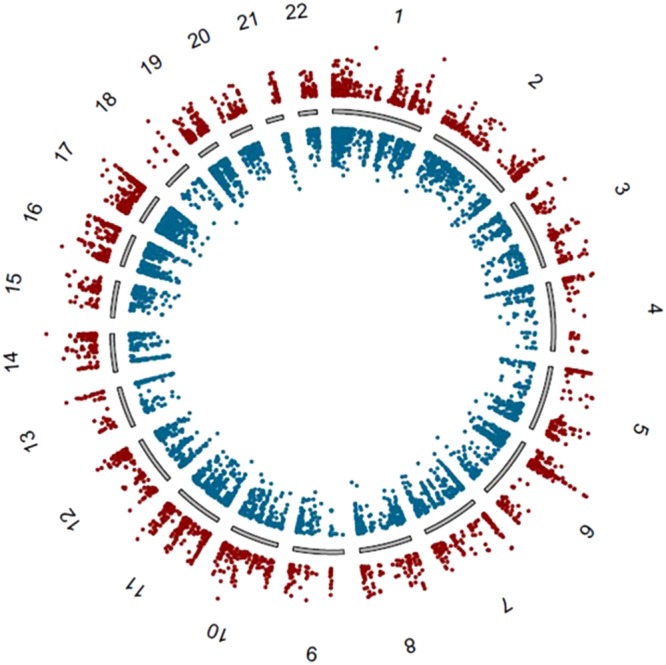

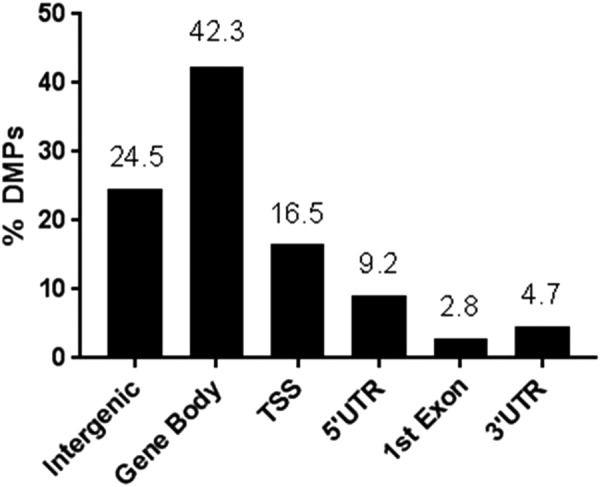

Table 1 shows the patient demographic for 24 MS patients and 24 healthy controls (Table 1). A total of 7618 CpGs met the criteria for a DMP (Table S1). Figure 1 shows the genome-wide distribution of differential methylation (Δmeth) for all DMPs. Amongst the DMPs, we observe an overall hypomethylation in MS cases, with 4731 (62%) of DMPs being hypomethylated and 2887 (38%) being hypermethylated in MS patients versus controls. When we considered genomic features for all DMPs we found 1869 (24.5%) map to intergenic regions, 3226 (42.3%) within the gene body, 1254 at the transcriptional start site (TSS1500 or TSS200) (16.5%), 699 in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) (9.2%), 211 map to the 1st exon (2.8%) and 359 in the 3′UTR (4.7%) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Subject demographics.

| Characteristic | MS participant (n = 24) | Control (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Age range (yrs) | 40.7 ± 8.5 | 43.3 ± 16.4 |

| EDSS | 2.4 ± 1.3 | |

| Disease duration (yrs) | 9.3 ± 6.6 | |

| Treatment (n) | ||

| • Naïve | 1 | |

| • OFF > 3 months | 4 | |

| • Interferon beta-1b | 2 | |

| • Interferon beta-1a | 3 | |

| • Glatiramer acetate | 2 | |

| • Natalizumab | 4 | |

| • Fingolimod | 8 |

Figure 1.

A genome-wide differential methylation plot. Data points outside the circle (red) represent increased methylation (i.e. ∆meth), in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients compared to controls whereas points inside the circle (blue) represent decreased methylation in MS patients compared to healthy controls.

Figure 2.

Distribution of DMPs over each of the genomic regions Y-axis represents proportion of total DMPs (7618) in each category (shown as percentage).

DMPs were ranked by Δmeth values. The two top ranked DMPs were located within the lymphotoxin alpha (LTA) gene (alias: tumor necrosis factor beta, TNFβ - hereafter referred to as LTA). These two sites had Δmeth values of 0.504 and 0.486 (50.4% and 48.6% hypermethylated respectively) in the MS patient group compared to the control group (P < 0.0001). Of the CpGs that met the criteria for a DMP, 19 are found in the LTA locus within a region of 860 bp. All sites are hypermethylated with Δmeth scores between 0.15 and 0.5 (between 15% and 50%) and are located within the TSS/5′UTR (Table 2).

Table 2.

DMR at LTA.

| IlmnID | MAPINFO | Element | Gene | Probe SNP | Probe SNPs10 | mean MS | mean HC | Δmeth | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg10995925 | 31539601 | TSS1500 | LTA | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 4.06E-04 | ||

| cg14441276 | 31539735 | TSS1500;TSS200 | LTA | rs56161754 | 0.59 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 4.06E-04 | |

| cg09621572 | 31539973 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs36221306 | rs56018225 | 0.66 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 4.57E-06 |

| cg14437551 | 31539986 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs36221306 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 1.04E-04 | |

| cg14597739 | 31539998 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs56207507 | rs36221306 | 0.74 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 1.04E-04 |

| cg16219283 | 31540002 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs56207507 | 0.72 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 1.04E-04 | |

| cg21999229 | 31540014 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs56207507 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 2.34E-05 | |

| cg17169196 | 31540026 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs36221309 | rs56207507 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 2.34E-05 |

| cg02402436 | 31540051 | TSS200;1stExon;5′UTR | LTA | rs36221309 | 0.47 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 4.57E-06 | |

| cg09736959 | 31540114 | 5′UTR | LTA | rs2239704 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 1.40E-03 | |

| cg24216966 | 31540121 | 5′UTR | LTA | rs2239704 | 0.73 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 1.04E-04 | |

| cg11586857 | 31540136 | 5′UTR | LTA | rs56245447 | rs2239704 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 1.04E-04 |

| cg10476003 | 31540169 | 5′UTR | LTA | rs56245447 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 4.57E-06 | |

| cg01157951 | 31540399 | 5′UTR | LTA | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 2.34E-05 | ||

| cg22318806 | 31540411 | 5′UTR | LTA | rs4986978 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 4.06E-04 | |

| cg13815684 | 31540440 | 5′UTR | LTA | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 1.04E-04 | ||

| cg17709873 | 31540456 | 5′UTR | LTA | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 4.32E-03 | ||

| cg16280132 | 31540459 | 5′UTR | LTA | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 1.04E-04 | ||

| cg26348243 | 31540461 | 5′UTR | LTA | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 2.34E-05 |

IlmnID = Illumina ID; MapINFO = genomic coordinates (Hg19); Element from UCSC RefGene; Probe SNP; Probe SNPs10.

Genetic influence at the LTA locus

One technical limitation of array technology is the influence that SNPs may have on the calculated methylation levels (β values). Of the 19 DMPs identified at the LTA TSS, 13 of the corresponding probes contain an adjacent SNP which may potentially influence the methylation profile (Table 2). Rather than remove these sites from our analysis, we assessed the genetic influence on the methylation signal by visualizing the distribution of β values.

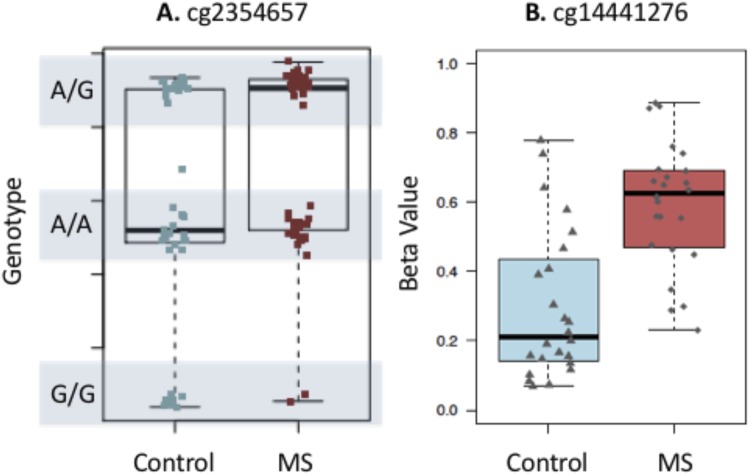

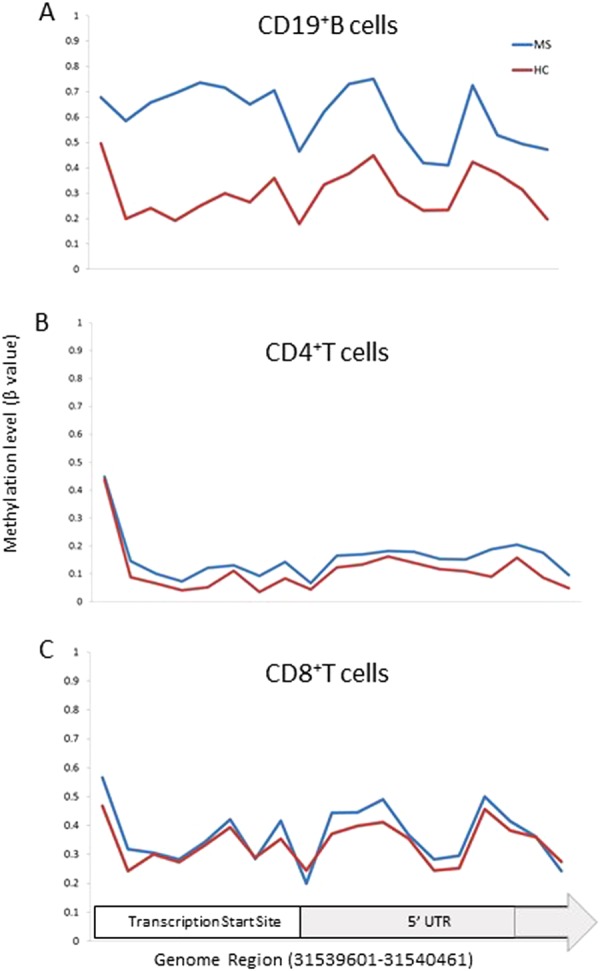

Figure 3A shows an example of a CpG site whose methylation signal is known to be influenced by a SNP located at this probe. This example shows that the β values cluster into 3 distinct regions representing the 3 possible genotypes (homozygous allele 1, homozygous allele 2 or heterozygous). Figure 3B shows the influence of SNPs on the top LTA CpG site in our DMR. The β values form a uniform spread, providing support that the SNP is not influencing the methylation signal at this particular CpG site. A similar result is seen in all DMPs within the LTA cluster (data not show). In addition to this, we compared the profiles of LTA in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells from our previous data sets with the same cohort. We found that hypermethylation at the LTA TSS appears to be specific to CD19+ B-cells, providing further support that the methylation effects observed in this cohort are at least partially exclusive from the underlying genotype (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Tukey box plot showing distribution of beta values for (A) a probe where the SNP is driving the methylation values and (B) the top LTA site from this study. The box plot shows the data within the interquartile range and the median is represented by a solid black line. Whiskers show maximum and minimum values. Grey bars indicate region for each genotype (homozygous allele 1 (1/1), heterozygous (1/2), and homozygous allele 2 (2/2)). Each point represents either an individual control (blue) or MS patients (red). Y axis shows β values.

Figure 4.

DMPs within the LTA TSS/5′UTR region Line graph showing the methylation level (β value) of MS cases (blue) versus controls (red) for the genomic region 31539601-31540461 for (A) CD19+ B cells (B) CD4+ T cells4,6 and (C) CD8+ T cells5. The region covers 19 probes contained within the LTA gene.

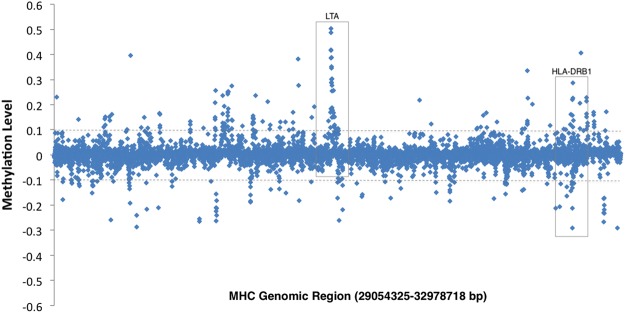

Differential methylation at other genes within the MHC locus

Our previous study in CD4+ T-cells identified a peak of differential methylation on chromosome 6 that mapped to the MHC region4. Specifically, we found a differentially methylated region that spanned 11 sites at the well-established MS risk gene, HLA-DRB1 that was unique to CD4+ T-cells4,5. To determine if there is any overlap of DMPs in the MHC region between CD4+ T-cells and CD19+ B-cells, we performed a closer analysis of the MHC region. Figure 5 shows that although a similar distinct peak is present at the MHC region, it corresponds primarily to the DMR at LTA and to a lesser extent HLA-DRB1. However, there are 4 DMPs in CD19+ B-cells that overlap with the sites found in CD4+ T-cells (Table 3). These sites correspond to probes cg04985482, cg06032479, cg17416722, and cg24147543. The first site maps to the MHC class I polypeptide related sequence A (MICA) locus and the remaining three sites all map to sites within HLA-DRB1. All sites are altered in the same direction (hypo- or hypermethylated) and have a similar differential methylation value in both cell subsets (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Methylation at the MHC locus in CD19+ B cells Manhattan plot showing methylation level (Δmeth) for all probes that fall within the MHC locus (Chr6: 29054321-32978719). Points above 0 represent hypermethylated sites, points below 0 represent hypomethylated sites. Grey dotted line indicates 10% change in methylation.

Table 3.

Common sites at the MHC locus in CD4 and CD19.

| IlmnID | CHR | MAPINFO | Gene | CD4 | CD19 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean MS | mean HC | Δmeth | P value | mean MS | mean HC | Δmeth | P value | ||||

| cg04985482 | 6 | 31382065 | MICA | 0.72 | 0.84 | −0.12 | 9.93E-03 | 0.73 | 0.84 | −0.11 | 2.99E-02 |

| cg06032479 | 6 | 32552026 | HLA-DRB1 | 0.65 | 0.75 | −0.10 | 7.00E-03 | 0.65 | 0.78 | −0.13 | 1.20E-02 |

| cg17416722 | 6 | 32554385 | HLA-DRB1 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 1.02E-03 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 1.40E-03 |

| cg24147543 | 6 | 32554481 | HLA-DRB1 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 6.44E-04 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 1.20E-02 |

Differential methylation at sites outside the MHC locus

To explore the importance of methylation outside the MHC region, we filtered DMPs outside the MHC to include only those contained within the TSS or 5′UTR (1953 DMPs). We chose the TSS and 5′UTR as an initial filtering step because DNA methylation that occurs in the promoter regions is generally associated with transcriptional repression, but its role elsewhere in the genome is more complex and less well understood15. We then further filtered the list to include only DMRs. A DMR was considered if i) there were 2 or more DMPs, ii) these DMPs fell within a 500 bp span iii) the DMPs were altered in the same direction. This generated a list of 276 genes which contained a DMR in their 5′UTR or TSS.

A comparison of this list to genes with a known association to MS2,3,16–18 revealed 4 DMRs (Table 4). Choline transporter-like 2 (SLC44A2) and Lymphotoxin β receptor (LTBR) each have 2 hypomethylated DMPs within their TSS/5′UTR which are 72 and 113 bp apart, respectively. Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 11 (CARD11) has 2 DMPs at the 5′UTR. Both of which are hypermethylated and 101 bp apart. There is a third DMP which is hypermethylated at the 5′UTR of CARD11; however, it is located >62,000 bp downstream of the DMR so it did not fulfil the criteria to be part of the DMR. At the TSS of the CXC chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5), there are 2 DMRS that are 9266 bp apart. The first of these has 5 hypermethylated DMPs within an 86 bp span. These DMPs are between 20.7% and 31.1% hypermethylated. The second contains 3 DMPs within 42 bp of each other that are 17.7%, 13.9% and 18% hypermethylated.

Table 4.

DMRs outside the MHC locus.

| IlmnID | CHR | MAPINFO | Gene | mean MS | mean HC | Δmeth | P value | Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg24041556 | 19 | 10736059 | SLC44A2 | 0.59 | 0.69 | −0.10 | 2.99E-02 | TSS200;Body |

| cg06561886 | 19 | 10736299 | SLC44A2 | 0.69 | 0.80 | −0.11 | 1.40E-03 | 5′UTR;1stExon;Body |

| cg24621362 | 12 | 6492890 | LTBR | 0.13 | 0.23 | −0.10 | 2.34E-05 | TSS1500 |

| cg23079808 | 12 | 6493003 | LTBR | 0.13 | 0.23 | −0.10 | 1.20E-02 | TSS1500 |

| cg19014792 | 7 | 3019159 | CARD11 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 4.32E-03 | 5′UTR |

| cg16495448 | 7 | 3019260 | CARD11 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 1.20E-02 | 5′UTR |

| cg14168009 | 7 | 3082006 | CARD11 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 4.06E-04 | 5′UTR |

| cg16235962 | 11 | 118754507 | CXCR5 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 1.04E-04 | TSS200 |

| cg04625873 | 11 | 118754530 | CXCR5 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 1.20E-02 | TSS200 |

| cg25087423 | 11 | 118754535 | CXCR5 | 0.71 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 1.20E-02 | TSS200 |

| cg26164712 | 11 | 118754565 | CXCR5 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 4.32E-03 | 5′UTR;1stExon |

| cg16280667 | 11 | 118754593 | CXCR5 | 0.61 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 4.06E-04 | 5′UTR;1stExon |

| cg04537602 | 11 | 118763859 | CXCR5 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 1.04E-04 | Body;TSS1500 |

| cg13298528 | 11 | 118763863 | CXCR5 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 2.34E-05 | Body;TSS1500 |

| cg19791714 | 11 | 118763901 | CXCR5 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 4.57E-06 | Body;TSS200 |

| cg07597976 | 16 | 28943019 | CD19 | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 4.06E-04 | TSS1500 |

| cg06323049 | 16 | 28943094 | CD19 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 1.20E-02 | TSS200 |

| cg27565966 | 16 | 28943198 | CD19 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 1.40E-03 | TSS200 |

| cg05433111 | 16 | 28943232 | CD19 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 1.40E-03 | TSS200 |

| cg01758575 | 16 | 28943288 | CD19 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 4.32E-03 | 1stExon;5′UTR |

| cg16454902 | 16 | 27414272 | IL21R | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.40E-03 | TSS200;5′UTR |

| cg02513379 | 16 | 27414281 | IL21R | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 4.57E-06 | TSS200;5′UTR |

| cg00050618 | 16 | 27414418 | IL21R | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 2.34E-05 | TSS200;5′UTR |

| cg02787852 | 16 | 27414536 | IL21R | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 1.06E-07 | 1stExon;5′UTR;5′UTR |

| cg10416668 | 16 | 27437730 | IL21R | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 1.20E-02 | TSS1500;5′UTR;5′UTR |

| cg25341726 | 16 | 28518331 | IL27 | 0.37 | 0.50 | −0.12 | 1.20E-02 | TSS200 |

| cg00201760 | 16 | 28518385 | IL27 | 0.32 | 0.45 | −0.13 | 1.20E-02 | TSS1500 |

Further analysis revealed several other DMRs outside the MHC region which reside in genes that may have biological significance to MS pathology. Of interest, there are 5 DMPs which lie within a 269 bp span at the cluster of differentiation 19 (CD19) locus. All are found within the TSS or 5′UTR and are hypermethylated by 22.4–30.7%. There is also a DMR at interleukin 21 receptor (IL21R) where 4 hypermethylated DMPs lie within a 264 bp span at the TSS.

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA)

The 7618 DMPs identified in the methylation analysis were located in 2899 genes. To assess the biological relevance of this gene set in terms of MS pathology we conducted a ORA using the WebGestalt engine to identify potential pathways associated with the 2899 gene set. Pathway analysis revealed significant alignment to innate immune system (293 genes, P = 4.08E-09), B-cell receptor signaling pathway (28 genes, P = 3.31E-04), cytokine signaling in Immune system (166 genes, 4.14E-04), and signaling by interleukins (119 genes, 1.46E-03). Table 5 shows the top 10 pathways identified.

Table 5.

Pathways Analysis of Genes with dysregulated DMPs.

| Pathway (BioSystems) | Source | No. of genes | FDR P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil degranulation | REACTOME | 138 | 9.20E-10 |

| Innate Immune System | REACTOME | 293 | 4.08E-09 |

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | KEGG | 40 | 8.88E-07 |

| Hemostasis | REACTOME | 150 | 3.16E-05 |

| Extracellular matrix organization | REACTOME | 80 | 1.54E-04 |

| Signalling events mediated by focal adhesion kinase | Pathway Interaction Database | 24 | 1.97E-04 |

| Phospholipase D signalling pathway | KEGG | 46 | 3.31E-04 |

| B cell receptor signalling pathway | KEGG | 28 | 3.31E-04 |

| Regulation of RAC1 activity | Pathway Interaction Database | 19 | 3.82E-04 |

| Cytokine Signalling in Immune system | REACTOME | 166 | 4.14E-04 |

Discussion

B-cells are gaining recognition in MS as potential regulators of disease pathology. In this study, we are the first to describe changes in the global DNA methylation profile in the CD19+ B-cells of MS patients compared to healthy controls. We find a slight overall hypomethylation and enrichment of genes involved in innate immunity and B-cell receptor and cytokine signaling pathways. We have identified a large, hypermethylated DMR in the TSS of LTA that is unique to the B-cell population. In addition, we identified four smaller DMRs at genes which contain known MS-associated SNPs, SLC44A2, LTBR, CXCR5, and CARD11.

The large DMR at LTA is of interest due to its longstanding, strong associations with MS. LTA encodes for the pro-inflammatory cytokine lymphotoxin-alpha (LT-α). LTA is over-expressed in CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ T-cells and CD19+ B-cells of RRMS patients19. Furthermore, in RRMS patients the LTA CSF/PBMC expression ratios are increased, and positively correlate with CD19 expression in CSF cells19. LTA producing cells have been found in the immediate vicinity of the demyelinating process in MS patients20 and expression is present in acute and chronic active brain lesions in MS patients21. One inconsistency is that we have shown hypermethylation in the TSS, which implies potential downregulation of transcription (as opposed to over-expression). The most likely explanation for this inconsistency is the presence of hydroxymethylation. Bisulfite conversion does not distinguish between hydroxymethylated and methylated sites; thus, both are considered methylated by the methods used in this study. Unlike methylation, which negatively correlates with transcription, hydroxymethylation has been found to positively correlate with active transcription22–25. Therefore, it is plausible that the methylation changes at LTA are due to changes in hydroxymethylation which would result in the overexpression seen in previous studies.

Another explanation for the inconsistency between our findings and previous studies could be due to transcript variants. LTA is known to have eight transcript variants, with multiple start sites26. Thus, the hypermethylation seen in our study may be related to an alternate transcriptional variant to that identified in previous studies. Alternately, previous studies were conducted primarily in treatment naïve patients, whereas our cohort only contains 1 treatment naïve sample. Therefore, hypermethylation and decreased LTA expression may be a result of treatment effects, or simply be reflective of disease stabilization.

Although we find DMRs at four other genes previously associated with MS, the functional significance of these DMRs is unclear. SLC44A2 is found in the peripheral tissues and has been associated with thrombosis and autoimmune hearing loss but not MS27. CXCR5 is used as the defining marker for follicular B helper T-cells (TFH) but its expression has not been demonstrated in B-cells28.

A recent study found LTBR expression levels increased in the animal model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), and that blockage of this receptor ameliorated disease in mice29. The same study investigated LTBR expression in RRMS patients and found increased transcript levels in patients who were resistant to interferon beta (IFNβ) therapy29. Hypomethylation in the TSS may be correlated with increased transcription of LTBR; however, the study by Inoue and colleagues used PBMCs, which contain a mixture of T-cells and B-cells, so it remains to be elucidated if increased expression is occurring in B-cells.

Although CARD11 does not yet have a demonstrated, functional role in MS, it is an essential scaffolding platform for the CARD11/ BCL10/MALT1 (CBM) complex30. NFκB governs the BCR-induced (B cell receptor) NFκB activation through a complex series of phosphorylation events that results in destruction of the NFκB inhibitor, IκB30. One known mechanism of action of the common MS therapy, dimethyl fumarate, is inhibition of the NFκB transcription factor; therefore, an intriguing possibility is that dysregulation of this pathway may play a role in MS pathology31.

Although not part of the MHC locus or previously linked to MS, IL21R is involved in other autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)32 and arthritis33. It has been linked to B-cell proliferation and survival as well as B-cell apoptosis which suggesting a role in immune cell function34,35.

Autoimmune diseases often have overlapping aetiological and genetic backgrounds36. In our previous studies, we found that there is also overlap in epigenetic profiles of CD4+ T-cells from SLE and MS patients6. Recently, Julià et al.37 assessed the DNA methylation profiles of B-cells from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients and performed a comparison with SLE patients37. To determine if there is overlap in the epigenetic profiles of CD19+ B-cells we compared our results to this study. Of the ten probes identified in their study, five also show differential methylation in the same direction (all hypermethylated) as in our study (Table 6). This suggests a common epigenetic precursor or epigenetic effect among related autoimmune diseases.

Table 6.

Probes which are differentially methylated in RA, SLE and MS.

| CpG | Chr | Gene | RA (n = 65 cases) Δmeth | SLE (n = 47 cases) Δmeth | MS (n = 24 cases) Δmeth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg18972751 | 1 | CD1C | 5.7 | 3.4 | 5.3 |

| cg09327855 | 1 | NID1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 10.2 |

| cg03055617 | 3 | TNFSF10 | −6.9 | −5.9 | |

| cg06613783 | 10 | SKIDA1 | 2.7 | 1.6 | |

| cg07285641 | 13 | DHRS12 | 1.7 | 1 | |

| cg01619562 | 14 | ITPK1 | 3.4 | 1.03 | 3.8 |

| cg01810713 | 16 | IRF8 | 3.1 | 10.1 | |

| cg04033022 | 16 | ACSF3 | 2.6 | 0.12 | 14.8 |

| cg00253346 | 22 | TNFRSF13C | 2 | 1.4 | 8.1 |

| cg08271031 | 22 | PARVG | 2.2 | 3 |

Bold = differential methylation in all three diseases. Based on ref.36. Julia A. et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2017; 26(14):2803-11.

One important consideration for our study is that the patients tested were taking various medications at the time of recruitment including interferons, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab and fingolimod. Only one patient was treatment naïve and 4 had been off treatment for more than 6 months. Although this study controlled for age, sex and treatment effects (as much as possible), due to our limited size we cannot control for changes associated with various environmental factors. Additionally, we were unable to control for B cell subtype compositions. As a third of the patients were taking fingolimod, this may have caused a significant change in the circulating cells.

This study adds to our knowledge of epigenetic factors in MS and further highlights the need to investigate individual cell subtypes when assessing DNA methylation in disease. It also raises several new and important questions including i) are these changes due to treatment effects ii) is the change in methylation at LTA due to hydroxymethylation iii) what role do environmental factors play on methylation changes iv) are the methylation effects due to changes in B cell subtypes and v) are DNA methylation changes a pre-disposing factor for MS or are they a result of disease pathology? Further studies are required using larger, treatment naïve cohorts that include epidemiological data will help extract if these results are due to treatment effects and allow the addition of environmental factors such as vitamin D, EBV virus infection and smoking as covariates in the analysis. Additionally, further studies should attempt to extrapolate the relative effect of methylation versus hydroxymethylation, possibly using a more targeted approach such as next generation sequencing. Overall, our results suggest that B-cell specific epigenetics may play a role in MS pathology. B-cell specific epigenetic therapies which target LTA expression would therefore be an attractive new avenue of research in MS treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the John Hunter Charitable Trust. R.A.L., V.E.M. and K.A.S. are supported by fellowships from Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia. K.A.S. was supported by a scholarship from the Trish foundation. V.E.M. is supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. We would like to thank the MS patients and clinical team at the John Hunter Hospital MS clinic who participated in this study and the Australia Red Cross Blood Service for providing healthy control samples. We also acknowledge the Analytical Biomolecular Research Facility at the University of Newcastle for flow cytometry support and the Australian Genome Research Facility for performing the bisulfite conversions and hybridizations to the Illumina 450 K arrays.

Author Contributions

V.E.M. performed experiments, was involved in interpretation of the data, wrote the manuscript and revised all versions of the manuscript. R.A.L. and M.C.B. performed data analysis, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. M.C.G. contributed to the original study design, performed experiments, and critically reviewed the manuscript. K.A.S. performed experiments and critically reviewed the manuscript. L.T. contributed to initial study design and critically reviewed the manuscript. J.L.S. and R.J.S. initiated and designed the original study, they critically reviewed the manuscript and are responsible for the infrastructure in which in the study was conducted. J.L.S. supervised all aspects of the study.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article (Supplementary Table 1). Raw data files are available from Assoc. Prof. Rodney A. Lea.

Competing Interests

Dr. Lechner-Scott’s institution receives non-directed funding as well as honoraria for presentations and membership on advisory boards from Sanofi Aventis, Biogen Idec, Bayer Health Care, Merck Serono, Teva and Novartis Australia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Vicki E. Maltby and Rodney A. Lea contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-35603-0.

References

- 1.Amato Maria Pia, Derfuss Tobias, Hemmer Bernard, Liblau Roland, Montalban Xavier, Soelberg Sørensen Per, Miller David H, Alfredsson Lars, Aloisi Francesca, Amato Maria Pia, Ascherio Alberto, Baldin Elisa, Bjørnevik Kjetil, Comabella Manuel, Correale Jorge, Cortese Marianna, Derfuss Tobias, D’Hooghe Marie, Ghezzi Angelo, Gold Julian, Hellwig Kerstin, Hemmer Bernhard, Koch-Henricksen Nils, Langer Gould Annette, Liblau Roland, Linker Ralf, Lolli Francesco, Lucas Robyn, Lünemann Jan, Magyari Melinda, Massacesi Luca, Miller Ariel, Miller David H, Montalban Xavier, Monteyne Philippe, Mowry Ellen, Münz Christian, Nielsen Nete M, Olsson Tomas, Oreja-Guevara Celia, Otero Susana, Pugliatti Maura, Reingold Stephen, Riise Trond, Robertson Neil, Salvetti Marco, Sidhom Youssef, Smolders Joost, Soelberg Sørensen Per, Sollid Ludvig, Steiner Israel, Stenager Egon, Sundstrom Peter, Taylor Bruce V, Tremlett Helen, Trojano Maria, Uccelli Antonio, Waubant Emmanuelle, Wekerle Hartmut. Environmental modifiable risk factors for multiple sclerosis: Report from the 2016 ECTRIMS focused workshop. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2017;24(5):590–603. doi: 10.1177/1352458516686847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics, C IL12A, MPHOSPH9/CDK2AP1 and RGS1 are novel multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Genes Immun11, 397–405, 10.1038/gene.2010.28 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Beecham Ashley H, Patsopoulos Nikolaos A, Xifara Dionysia K, Davis Mary F, Kemppinen Anu, Cotsapas Chris, Shah Tejas S, Spencer Chris, Booth David, Goris An, Oturai Annette, Saarela Janna, Fontaine Bertrand, Hemmer Bernhard, Martin Claes, Zipp Frauke, D'Alfonso Sandra, Martinelli-Boneschi Filippo, Taylor Bruce, Harbo Hanne F, Kockum Ingrid, Hillert Jan, Olsson Tomas, Ban Maria, Oksenberg Jorge R, Hintzen Rogier, Barcellos Lisa F, Agliardi Cristina, Alfredsson Lars, Alizadeh Mehdi, Anderson Carl, Andrews Robert, Søndergaard Helle Bach, Baker Amie, Band Gavin, Baranzini Sergio E, Barizzone Nadia, Barrett Jeffrey, Bellenguez Céline, Bergamaschi Laura, Bernardinelli Luisa, Berthele Achim, Biberacher Viola, Binder Thomas M C, Blackburn Hannah, Bomfim Izaura L, Brambilla Paola, Broadley Simon, Brochet Bruno, Brundin Lou, Buck Dorothea, Butzkueven Helmut, Caillier Stacy J, Camu William, Carpentier Wassila, Cavalla Paola, Celius Elisabeth G, Coman Irène, Comi Giancarlo, Corrado Lucia, Cosemans Leentje, Cournu-Rebeix Isabelle, Cree Bruce A C, Cusi Daniele, Damotte Vincent, Defer Gilles, Delgado Silvia R, Deloukas Panos, di Sapio Alessia, Dilthey Alexander T, Donnelly Peter, Dubois Bénédicte, Duddy Martin, Edkins Sarah, Elovaara Irina, Esposito Federica, Evangelou Nikos, Fiddes Barnaby, Field Judith, Franke Andre, Freeman Colin, Frohlich Irene Y, Galimberti Daniela, Gieger Christian, Gourraud Pierre-Antoine, Graetz Christiane, Graham Andrew, Grummel Verena, Guaschino Clara, Hadjixenofontos Athena, Hakonarson Hakon, Halfpenny Christopher, Hall Gillian, Hall Per, Hamsten Anders, Harley James, Harrower Timothy, Hawkins Clive, Hellenthal Garrett, Hillier Charles, Hobart Jeremy, Hoshi Muni, Hunt Sarah E, Jagodic Maja, Jelčić Ilijas, Jochim Angela, Kendall Brian, Kermode Allan, Kilpatrick Trevor, Koivisto Keijo, Konidari Ioanna, Korn Thomas, Kronsbein Helena, Langford Cordelia, Larsson Malin, Lathrop Mark, Lebrun-Frenay Christine, Lechner-Scott Jeannette, Lee Michelle H, Leone Maurizio A, Leppä Virpi, Liberatore Giuseppe, Lie Benedicte A, Lill Christina M, Lindén Magdalena, Link Jenny, Luessi Felix, Lycke Jan, Macciardi Fabio, Männistö Satu, Manrique Clara P, Martin Roland, Martinelli Vittorio, Mason Deborah, Mazibrada Gordon, McCabe Cristin, Mero Inger-Lise, Mescheriakova Julia, Moutsianas Loukas, Myhr Kjell-Morten, Nagels Guy, Nicholas Richard, Nilsson Petra, Piehl Fredrik, Pirinen Matti, Price Siân E, Quach Hong, Reunanen Mauri, Robberecht Wim, Robertson Neil P, Rodegher Mariaemma, Rog David, Salvetti Marco, Schnetz-Boutaud Nathalie C, Sellebjerg Finn, Selter Rebecca C, Schaefer Catherine, Shaunak Sandip, Shen Ling, Shields Simon, Siffrin Volker, Slee Mark, Sorensen Per Soelberg, Sorosina Melissa, Sospedra Mireia, Spurkland Anne, Strange Amy, Sundqvist Emilie, Thijs Vincent, Thorpe John, Ticca Anna, Tienari Pentti, van Duijn Cornelia, Visser Elizabeth M, Vucic Steve, Westerlind Helga, Wiley James S, Wilkins Alastair, Wilson James F, Winkelmann Juliane, Zajicek John, Zindler Eva, Haines Jonathan L, Pericak-Vance Margaret A, Ivinson Adrian J, Stewart Graeme, Hafler David, Hauser Stephen L, Compston Alastair, McVean Gil, De Jager Philip, Sawcer Stephen J, McCauley Jacob L. Analysis of immune-related loci identifies 48 new susceptibility variants for multiple sclerosis. Nature Genetics. 2013;45(11):1353–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves M, et al. Methylation differences at the HLA-DRB1 locus in CD4+ T-Cells are associated with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;20:1033–1041. doi: 10.1177/1352458513516529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maltby VE, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of CD8+ T cells shows a distinct epigenetic signature to CD4+ T cells in multiple sclerosis patients. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:118. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maltby VE, et al. Differential methylation at MHC in CD4+ T cells is associated with multiple sclerosis independently of HLA-DRB1. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:71. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0371-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos SD, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles indicate CD8+ T cell hypermethylation in multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranzini SE, et al. Genome, epigenome and RNA sequences of monozygotic twins discordant for multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2010;464:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nature08990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin R, Sospedra M, Rosito M, Engelhardt B. Current multiple sclerosis treatments have improved our understanding of MS autoimmune pathogenesis. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:2078–2090. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann-Horn Klaus, Kinzel Silke, Weber Martin. Deciphering the Role of B Cells in Multiple Sclerosis—Towards Specific Targeting of Pathogenic Function. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(10):2048. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauser SL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:676–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kappos L, et al. Ocrelizumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1779–1787. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson Alan J, Banwell Brenda L, Barkhof Frederik, Carroll William M, Coetzee Timothy, Comi Giancarlo, Correale Jorge, Fazekas Franz, Filippi Massimo, Freedman Mark S, Fujihara Kazuo, Galetta Steven L, Hartung Hans Peter, Kappos Ludwig, Lublin Fred D, Marrie Ruth Ann, Miller Aaron E, Miller David H, Montalban Xavier, Mowry Ellen M, Sorensen Per Soelberg, Tintoré Mar, Traboulsee Anthony L, Trojano Maria, Uitdehaag Bernard M J, Vukusic Sandra, Waubant Emmanuelle, Weinshenker Brian G, Reingold Stephen C, Cohen Jeffrey A. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 2018;17(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Schmidt B. Long read alignment based on maximal exact match seeds. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:i318–i324. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schubeler D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature. 2015;517:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature14192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patsopoulos NA, et al. Fine-mapping the genetic association of the major histocompatibility complex in multiple sclerosis: HLA and non-HLA effects. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics, C. et al. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med357, 851–862, 10.1056/NEJMoa073493 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sawcer Stephen, Hellenthal Garrett, Pirinen Matti, Spencer Chris C. A., Patsopoulos Nikolaos A., Moutsianas Loukas, Dilthey Alexander, Su Zhan, Freeman Colin, Hunt Sarah E., Edkins Sarah, Gray Emma, Booth David R., Potter Simon C., Goris An, Band Gavin, Bang Oturai Annette, Strange Amy, Saarela Janna, Bellenguez Céline, Fontaine Bertrand, Gillman Matthew, Hemmer Bernhard, Gwilliam Rhian, Zipp Frauke, Jayakumar Alagurevathi, Martin Roland, Leslie Stephen, Hawkins Stanley, Giannoulatou Eleni, D’alfonso Sandra, Blackburn Hannah, Martinelli Boneschi Filippo, Liddle Jennifer, Harbo Hanne F., Perez Marc L., Spurkland Anne, Waller Matthew J., Mycko Marcin P., Ricketts Michelle, Comabella Manuel, Hammond Naomi, Kockum Ingrid, McCann Owen T., Ban Maria, Whittaker Pamela, Kemppinen Anu, Weston Paul, Hawkins Clive, Widaa Sara, Zajicek John, Dronov Serge, Robertson Neil, Bumpstead Suzannah J., Barcellos Lisa F., Ravindrarajah Rathi, Abraham Roby, Alfredsson Lars, Ardlie Kristin, Aubin Cristin, Baker Amie, Baker Katharine, Baranzini Sergio E., Bergamaschi Laura, Bergamaschi Roberto, Bernstein Allan, Berthele Achim, Boggild Mike, Bradfield Jonathan P., Brassat David, Broadley Simon A., Buck Dorothea, Butzkueven Helmut, Capra Ruggero, Carroll William M., Cavalla Paola, Celius Elisabeth G., Cepok Sabine, Chiavacci Rosetta, Clerget-Darpoux Françoise, Clysters Katleen, Comi Giancarlo, Cossburn Mark, Cournu-Rebeix Isabelle, Cox Mathew B., Cozen Wendy, Cree Bruce A. C., Cross Anne H., Cusi Daniele, Daly Mark J., Davis Emma, de Bakker Paul I. W., Debouverie Marc, D’hooghe Marie Beatrice, Dixon Katherine, Dobosi Rita, Dubois Bénédicte, Ellinghaus David, Elovaara Irina, Esposito Federica, Fontenille Claire, Foote Simon, Franke Andre, Galimberti Daniela, Ghezzi Angelo, Glessner Joseph, Gomez Refujia, Gout Olivier, Graham Colin, Grant Struan F. A., Rosa Guerini Franca, Hakonarson Hakon, Hall Per, Hamsten Anders, Hartung Hans-Peter, Heard Rob N., Heath Simon, Hobart Jeremy, Hoshi Muna, Infante-Duarte Carmen, Ingram Gillian, Ingram Wendy, Islam Talat, Jagodic Maja, Kabesch Michael, Kermode Allan G., Kilpatrick Trevor J., Kim Cecilia, Klopp Norman, Koivisto Keijo, Larsson Malin, Lathrop Mark, Lechner-Scott Jeannette S., Leone Maurizio A., Leppä Virpi, Liljedahl Ulrika, Lima Bomfim Izaura, Lincoln Robin R., Link Jenny, Liu Jianjun, Lorentzen Åslaug R., Lupoli Sara, Macciardi Fabio, Mack Thomas, Marriott Mark, Martinelli Vittorio, Mason Deborah, McCauley Jacob L., Mentch Frank, Mero Inger-Lise, Mihalova Tania, Montalban Xavier, Mottershead John, Myhr Kjell-Morten, Naldi Paola, Ollier William, Page Alison, Palotie Aarno, Pelletier Jean, Piccio Laura, Pickersgill Trevor, Piehl Fredrik, Pobywajlo Susan, Quach Hong L., Ramsay Patricia P., Reunanen Mauri, Reynolds Richard, Rioux John D., Rodegher Mariaemma, Roesner Sabine, Rubio Justin P., Rückert Ina-Maria, Salvetti Marco, Salvi Erika, Santaniello Adam, Schaefer Catherine A., Schreiber Stefan, Schulze Christian, Scott Rodney J., Sellebjerg Finn, Selmaj Krzysztof W., Sexton David, Shen Ling, Simms-Acuna Brigid, Skidmore Sheila, Sleiman Patrick M. A., Smestad Cathrine, Sørensen Per Soelberg, Søndergaard Helle Bach, Stankovich Jim, Strange Richard C., Sulonen Anna-Maija, Sundqvist Emilie, Syvänen Ann-Christine, Taddeo Francesca, Taylor Bruce, Blackwell Jenefer M., Tienari Pentti, Bramon Elvira, Tourbah Ayman, Brown Matthew A., Tronczynska Ewa, Casas Juan P., Tubridy Niall, Corvin Aiden, Vickery Jane, Jankowski Janusz, Villoslada Pablo, Markus Hugh S., Wang Kai, Mathew Christopher G., Wason James, Palmer Colin N. A., Wichmann H-Erich, Plomin Robert, Willoughby Ernest, Rautanen Anna, Winkelmann Juliane, Wittig Michael, Trembath Richard C., Yaouanq Jacqueline, Viswanathan Ananth C., Zhang Haitao, Wood Nicholas W., Zuvich Rebecca, Deloukas Panos, Langford Cordelia, Duncanson Audrey, Oksenberg Jorge R., Pericak-Vance Margaret A., Haines Jonathan L., Olsson Tomas, Hillert Jan, Ivinson Adrian J., De Jager Philip L., Peltonen Leena, Stewart Graeme J., Hafler David A., Hauser Stephen L., McVean Gil, Donnelly Peter, Compston Alastair. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476(7359):214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romme Christensen J, et al. Cellular sources of dysregulated cytokines in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:215. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matusevicius D, et al. Multiple sclerosis: the proinflammatory cytokines lymphotoxin-alpha and tumour necrosis factor-alpha are upregulated in cerebrospinal fluid mononuclear cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;66:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(96)00032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selmaj K, Raine CS, Cannella B, Brosnan CF. Identification of lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:949–954. doi: 10.1172/JCI115102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nestor CE, et al. Tissue type is a major modifier of the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine content of human genes. Genome Res. 2012;22:467–477. doi: 10.1101/gr.126417.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastor WA, et al. Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:394–397. doi: 10.1038/nature10102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ficz G, et al. Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature. 2011;473:398–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin SG, Wu X, Li AX, Pfeifer GP. Genomic mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the human brain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5015–5024. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokley BH, Selby ST, Posch PE. A stimulation-dependent alternate core promoter links lymphotoxin alpha expression with TGF-beta1 and fibroblast growth factor-7 signaling in primary human T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:4573–4584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Traiffort E, O’Regan S, Ruat M. The choline transporter-like family SLC44: properties and roles in human diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moser B. CXCR5, the Defining Marker for Follicular B Helper T (TFH) Cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:296. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue M, et al. An interferon-beta-resistant and NLRP3 inflammasome-independent subtype of EAE with neuronal damage. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1599–1609. doi: 10.1038/nn.4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sommer K, et al. Phosphorylation of the CARMA1 linker controls NF-kappaB activation. Immunity. 2005;23:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pistono C, et al. What’s new about oral treatments in Multiple Sclerosis? Immunogenetics still under question. Pharmacol Res. 2017;120:279–293. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herber D, et al. IL-21 has a pathogenic role in a lupus-prone mouse model and its blockade with IL-21R.Fc reduces disease progression. J Immunol. 2007;178:3822–3830. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jungel A, et al. Expression of interleukin-21 receptor, but not interleukin-21, in synovial fibroblasts and synovial macrophages of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1468–1476. doi: 10.1002/art.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozaki K, et al. Regulation of B cell differentiation and plasma cell generation by IL-21, a novel inducer of Blimp-1 and Bcl-6. J Immunol. 2004;173:5361–5371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta DS, et al. IL-21 induces the apoptosis of resting and activated primary B cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:4111–4118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parkes M, Cortes A, van Heel DA, Brown MA. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:661–673. doi: 10.1038/nrg3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Julia A, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of rheumatoid arthritis identifies differentially methylated loci in B cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:2803–2811. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article (Supplementary Table 1). Raw data files are available from Assoc. Prof. Rodney A. Lea.