Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) expresses a number of tegument proteins that interfere with the intrinsic and the innate defense mechanisms of the cell. Initial induction of the interferon-stimulated gene 15 protein (ISG15) and conjugation of proteins with ISG15 (ISGylation) by HCMV infection are subsequently attenuated by the expression of the viral IE1, pUL50, and pUL26 proteins. This study adds pUL25 as another factor that contributes to suppression of ISGylation. The tegument protein interacts with pUL26 and prevents its degradation by the proteasome. By doing this, it supports its restrictive influence on ISGylation. In addition, a lack of pUL25 enhances the levels of free ISG15, indicating that the tegument protein may interfere with the interferon response on levels other than interacting with pUL26. Knowledge obtained in this study widens our understanding of HCMV immune evasion and may also provide a new avenue for the use of pUL25-negative strains for vaccine production.

KEYWORDS: dense bodies, ISG15, ISGylation, cytomegalovirus, pUL25, pUL26, pp65, tegument

ABSTRACT

The tegument of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) virions contains proteins that interfere with both the intrinsic and the innate immunity. One protein with a thus far unknown function is pUL25. The deletion of pUL25 in a viral mutant (Towne-ΔUL25) had no impact on the release of virions and subviral dense bodies or on virion morphogenesis. Proteomic analyses showed few alterations in the overall protein composition of extracellular particles. A surprising result, however, was the almost complete absence of pUL26 in virions and dense bodies of Towne-ΔUL25 and a reduction of the large isoform pUL26-p27 in mutant virus-infected cells. pUL26 had been shown to inhibit protein conjugation with the interferon-stimulated gene 15 protein (ISG15), thereby supporting HCMV replication. To test for a functional relationship between pUL25 and pUL26, we addressed the steady-state levels of pUL26 and found them to be reduced in Towne-ΔUL25-infected cells. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments proved an interaction between pUL25 and pUL26. Surprisingly, the overall protein ISGylation was enhanced in Towne-ΔUL25-infected cells, thus mimicking the phenotype of a pUL26-deleted HCMV mutant. The functional relevance of this was confirmed by showing that the replication of Towne-ΔUL25 was more sensitive to beta interferon. The increase of protein ISGylation was also seen in cells infected with a mutant lacking the tegument protein pp65. Upon retesting, we found that pUL26 degradation was also increased when pp65 was unavailable. Our experiments show that both pUL25 and pp65 regulate pUL26 degradation and the pUL26-dependent reduction of ISGylation and add pUL25 as another HCMV tegument protein that interferes with the intrinsic immunity of the host cell.

IMPORTANCE Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) expresses a number of tegument proteins that interfere with the intrinsic and the innate defense mechanisms of the cell. Initial induction of the interferon-stimulated gene 15 protein (ISG15) and conjugation of proteins with ISG15 (ISGylation) by HCMV infection are subsequently attenuated by the expression of the viral IE1, pUL50, and pUL26 proteins. This study adds pUL25 as another factor that contributes to suppression of ISGylation. The tegument protein interacts with pUL26 and prevents its degradation by the proteasome. By doing this, it supports its restrictive influence on ISGylation. In addition, a lack of pUL25 enhances the levels of free ISG15, indicating that the tegument protein may interfere with the interferon response on levels other than interacting with pUL26. Knowledge obtained in this study widens our understanding of HCMV immune evasion and may also provide a new avenue for the use of pUL25-negative strains for vaccine production.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) severely affects individuals with impaired or immature immune defense functions (1). Being a member of the family Betaherpesvirinae, it shares the typical morphology of herpesviruses. An icosahedral capsid containing the large DNA genome associates with capsid-associated tegument proteins at its outer surface (2). This interaction is thought to stabilize the capsid to oppose the immense pressure imparted by the requirement of the capsid to accommodate the large genome (3). This capsid-tegument structure is embedded in an outer layer of tegument proteins. During the process of secondary envelopment in the cytoplasm, the HCMV particle finally acquires its envelope containing protein complexes which are essential for subsequent infection events (4). Parallel to virion morphogenesis, subviral dense bodies (DBs) are assembled and released following infection with laboratory HCMV strains and, to lesser extent, following infection with HCMV recent isolates (5; C. Sauer and B. Plachter, unpublished data).

The outer tegument of HCMV virions contains a number of proteins whose functions are only incompletely understood. Some of these outer tegument proteins are abundant constituents of virions (6–8). Despite their abundance, the lack of some of these proteins leaves viral replication in cell culture and virion morphogenesis relatively unaffected (9, 10). Deletion of the gene encoding the most abundant tegument protein, pp65 (pUL83), has only a limited impact on the composition of virions and on viral productivity (8). This argues in favor of a remarkable flexibility of the outer tegument of HCMV with respect to particle morphogenesis. Still, cellular transport and the coordinate interaction of the outer tegument proteins appear to be important, as only slight modifications disturbing these processes may suffice to impair progeny production (11).

Infection with HCMV leads to the release of type I interferons (IFNs) from infected cells. The release of IFNs, via their engagement with interferon receptors on the cell surface, leads to the downstream induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Many of the gene products of ISGs have antiviral functions. Some of the outer tegument proteins serve important functions by interfering with interferon-induced defense mechanisms against viral infection (12–22). It was shown that pp65 subverts the DNA-sensing function of the cellular interferon-inducible protein 16 (IFI-16), thereby attenuating its antiviral effect (21). pp65 may also interfere with innate immunity at other levels (reviewed in reference 13). Only recently, pUL26 has been identified to be a viral protein affecting the conjugation of the interferon-stimulated gene 15 product (ISG15) to nascent proteins (16). The current thinking is that ISG15, a ubiquitin-like protein modifier, is covalently attached to all de novo-synthesized proteins as a response to viral infection. This ISGylation tags viral and cellular proteins for degradation, thereby limiting viral replication (23). pUL26 is thought to interfere with ISGylation, thereby alleviating that block of HCMV replication (16).

Although there is increasing knowledge about the role of some of the outer tegument proteins in HCMV morphogenesis and replication, there are still a number of these proteins with thus far unknown functions. One of these is pUL25. Early studies identified pUL25 to be a phosphoprotein of 85 kDa with a cytoplasmic location in infected cells (24). It was shown to be expressed with late kinetics and localized to cytoplasmic virus assembly compartments (cVAC). Using immunoelectron microscopy, an association with intracellular virions and DBs was described (25). Later analyses showed that pUL25 is an abundant tegument protein of virions with even enhanced packaging into DBs (6, 8, 26).

In this study, we addressed pUL25 and its role in HCMV virion assembly and replication. Using an HCMV deletion mutant and label-free mass spectrometry (MS), only modest changes in the composition of pUL25-negative virions and DBs were detectable. In contrast to other tegument proteins, pUL26 was almost absent in these pUL25-negative extracellular particles. We found that pUL26 was unstable in cells infected with the pUL25 mutant, explaining its limited detectability in progeny particles. Cells infected with pUL25-negative viruses showed enhanced ISGylation and susceptibility to beta interferon (IFN-β) treatment. The presented data indicate that the pUL25-pUL26 interaction is important for HCMV-induced interference with ISGylation.

RESULTS

A deletion mutant of UL25 shows impaired initiation of DNA replication.

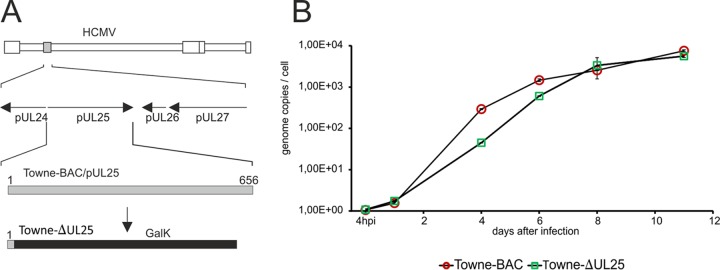

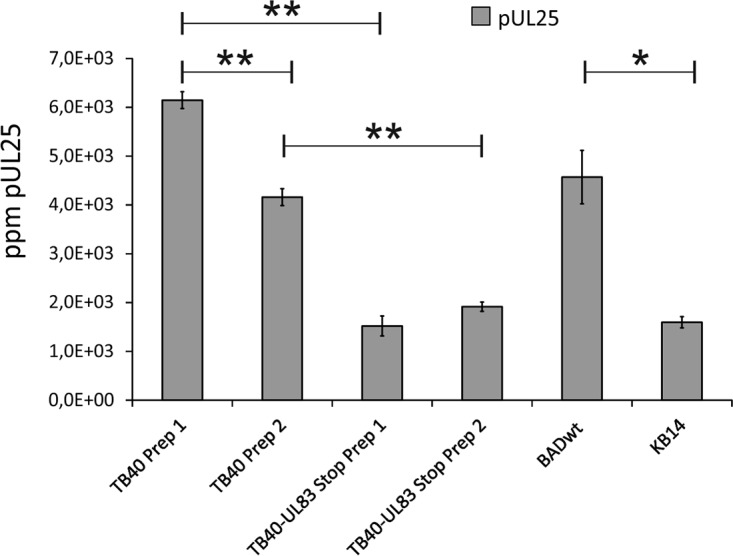

The function of HCMV pUL25 has not been properly addressed. Being one of the most abundant outer tegument proteins, we figured that pUL25 might serve some important function in the morphogenesis of HCMV virions. We first addressed the question of whether the abrogation of the expression of pp65 (the most abundant tegument protein) might lead to a compensatory incorporation of pUL25 into virions. We compared the protein contents of virions from two different HCMV strains for which pp65-negative variants were available to us. This was done using quantitative label-free mass spectrometry. The results showed that UL83 deletion led to a reduced rather than an enhanced upload of pUL25 into pp65-negative virions (Fig. 1). To be able to further address the role of pUL25 during HCMV infection, a mutant devoid of UL25 was generated in the genetic background of HCMV strain Towne using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) mutagenesis (Fig. 2A). The respective virus was denoted Towne-ΔUL25. To test whether the deletion of UL25 affected the initiation of viral DNA replication, human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were infected at a low a multiplicity of infection (MOI; 1 genome copy/cell, measured at 4 h postinfection). Cells were collected at different intervals after infection. DNA preparations from cell lysates were subjected to quantitative TaqMan PCR analysis (Fig. 2B). The results showed that the initiation of DNA replication was delayed following Towne-ΔUL25 infection. The levels of genomic DNA, however, reached levels similar to those of the control (Towne) at later stages of infection. The results were confirmed in a second, independent experiment.

FIG 1.

pUL25 is packaged into virions of different HCMV strains in a pp65-dependent manner. Label-free quantitative mass spectrometry was used to determine the amount of pUL25 in virions of different pp65-positive and pp65-negative HCMV strains. TB40-UL83 Stop is a derivative of strain TB40 with stop codons interrupting the pp65 open reading frame. KB14 is a derivative of the BADwt strain with a deletion of the pp65 open reading frame. Strains TB40 and TB40-UL83 Stop were evaluated using two independent biological replicates (preparation 1 [Prep 1] and preparation 2 [Prep 2]). The means for four technical replicates of each sample were measured in parts per million (ppm). Bars represent the standard error. Differences between samples were evaluated by Student’s t test. **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.01. The results confirm and extend the results of a previous study from our laboratories (8).

FIG 2.

Generation of a UL25 deletion mutant. (A) Schematic representation of the mutagenesis strategy used. The location of the UL25 gene with respect to neighboring genes is shown by arrows. Towne-ΔUL25 was generated by inserting a galK expression cassette into the UL25 open reading frame. The first 287 bp of UL25 remained in the BAC sequence in order to preserve the promoter region of the neighboring UL24 gene. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of the genome replication of Towne-ΔUL25 versus that of Towne. Cells were infected in a way to achieve comparable genome copy numbers in the cells at 4 h after infection (reference point). Samples were drawn at the indicated time points and were subjected to quantitative TaqMan PCR analysis. The values represent the means for 3 technical replicates. Error bars are indicated. The data represent those from one of two biological replicates.

Deletion of UL25 does not alter particle formation and release and has a limited impact on the outer tegument protein uploaded into virions and DBs.

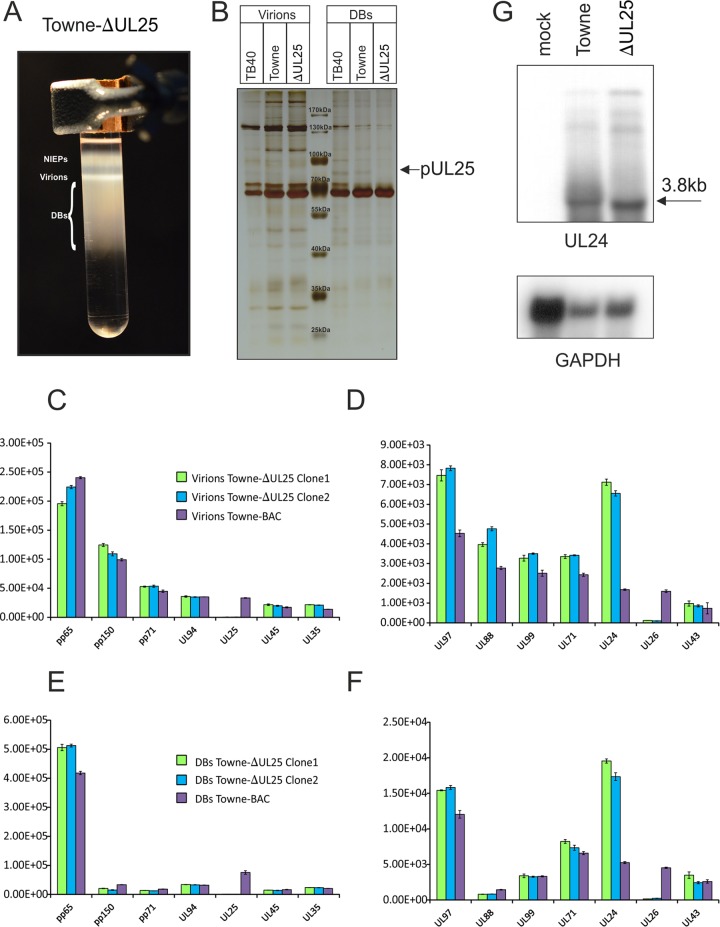

To investigate if the lack of the abundant tegument protein pUL25 had an impact on particle morphogenesis, HFF were infected with Towne-ΔUL25. Virions and DBs were purified, using glycerol tartrate gradient centrifugation (Fig. 3A). The material was loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel along with the corresponding specimens of the parental Towne strain and the TB40 strain. The resulting protein patterns of virions and DBs of the three strains were compared following silver staining. The only apparent difference was the lack of a protein band of roughly 80 kDa, corresponding to pUL25 in the DB preparations of Towne-ΔUL25 (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Analysis of Towne-ΔUL25 with respect to virion morphogenesis and UL24 transcription. (A) Purification of DBs, virions, and noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPs) by glycerol-tartrate ultracentrifugation. The different fractions are indicated. (B) Separation of purified virion and DB fractions from the indicated strains by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Proteins were visualized by silver staining. Molecular weight markers and the putative position of pUL25 are indicated. (C to F) Mass spectrometry of the outer tegument protein composition of the virions and DBs of two different clones of Towne-ΔUL25 and of Towne. The means for three technical replicates of each sample were measured in parts per million (ppm), and the values are indicated on the y axis. Bars represent the standard error. (C and D) Proteome of virions; (E and F) proteome of DBs. Note the different scales in panels C and E versus panels D and F. A separate analysis confirming the lack of an impact of pUL25 expression on the overall protein composition of virions and DBs was performed (not shown). (G) Northern blot analysis of the transcription from the UL25-flanking gene UL24. Total cell RNA, prepared from 5-day-infected or mock-infected cells, was subjected to formaldehyde agarose gel electrophoresis. Following transfer, filters were hybridized to a UL24-specific probe. An RNA of 3.8 kb corresponding to a transcript terminating at the 3′ end of UL21a could be detected.

To analyze the protein pattern of virions and DBs more accurately, label-free mass spectrometry was again used. The results confirmed the lack of pUL25 in virions and DBs of Towne-ΔUL25 (Fig. 3C and E). Packaging of most of the other tegument proteins was unaffected by pUL25 deletion (Fig. 3C to F). The most remarkable result of the proteomic analysis was the finding that pUL26 was almost completely absent in pUL25-negative virions and DBs, indicating that its presence in HCMV particles was dependent on the presence of pUL25 in infected cells. We thus decided to analyze this in further detail (see below).

Only pUL24 was enhanced in its upload when two biological replicates were evaluated. To investigate if this was related to enhanced expression from the UL24 gene, Northern blot analyses were performed using total cellular RNA that was isolated from fibroblasts that had been infected with Towne or Towne-ΔUL25 for 5 days. Hybridization with a UL24-specific probe showed a prominent band of roughly 3.8 kb (Fig. 3G). Inspection of the nucleotide sequence revealed that a polyadenylation sequence could not be found immediately 3′ to the UL24 open reading frame. A polyadenylation sequence was found close to the 3’end of UL21a. Termination of the UL24 RNA at this site would give rise to a transcript of the detected size. No differences in the intensity of the 3.8-kb RNA could be found, using GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) RNA as a standard. This indicates that the enhanced packaging of pUL24 into viral particles was not the result of enhanced expression. Further studies will have to focus on the relevance of pUL24 for virion morphogenesis.

Virion and DB morphogenesis is indistinguishable in cells infected with Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne.

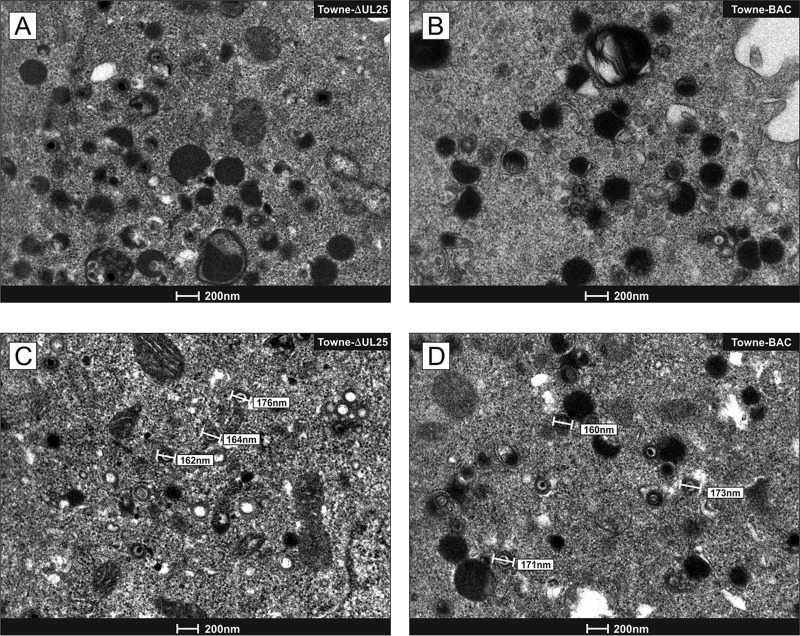

To investigate if the lack of pUL25 altered cytoplasmic particle morphogenesis, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on HFF that had been infected with Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne (Fig. 4). Cells were infected with the respective viruses for 6 days and were subsequently processed for TEM. Cytoplasmic assembly compartments became immediately apparent upon inspection. In Towne-ΔUL25- or Towne-infected cells, virions and DBs were detectable without apparent differences in morphology between the two strains. As an impact on virion size had been reported in a mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) M25 mutant, we measured the diameters of the cytoplasmic virions. In contrast to MCMV, no differences between the virions of Towne-ΔUL25 and Towne were found.

FIG 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of cells infected with either Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne. (A and C) Images of cytoplasmic virion and DB formation in human foreskin fibroblasts infected with Towne-ΔUL25. (B and D) Images of cytoplasmic virion and DB formation in human foreskin fibroblasts infected with Towne. Bars indicate the diameters of the virions of both strains.

The levels of pUL26 are reduced in cells infected with either a pUL25-negative or a pp65-negative HCMV mutant.

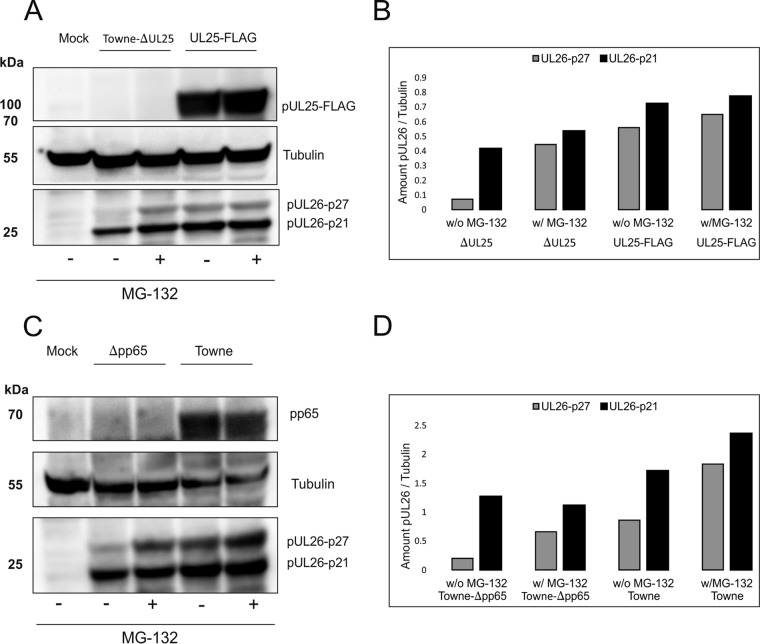

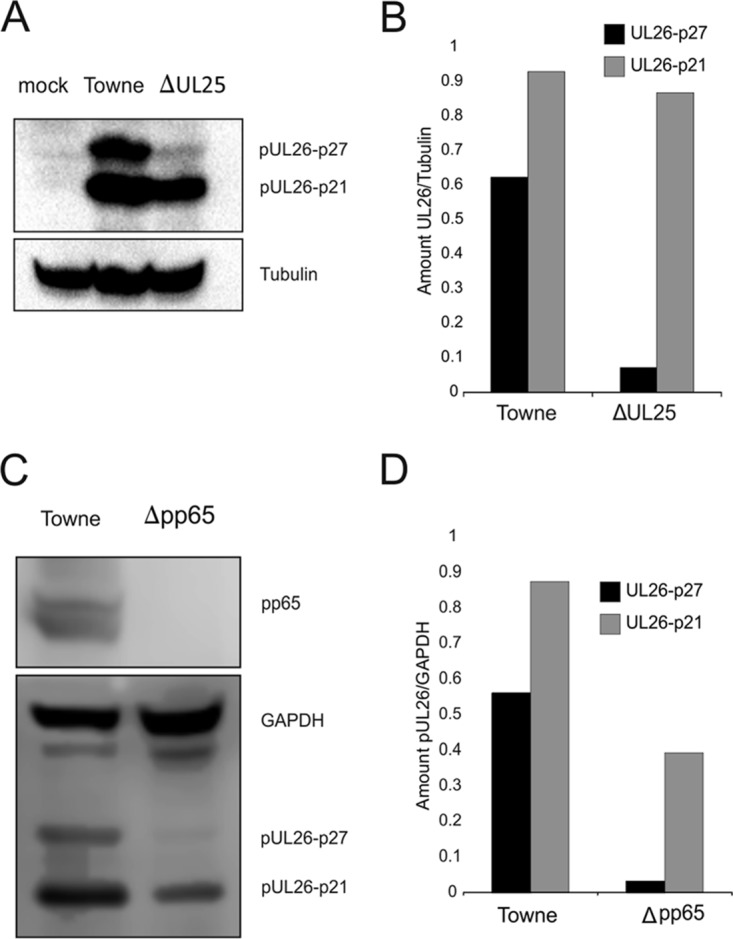

Results from quantitative mass spectrometry indicated that pUL26 was packaged in reduced amounts into the virions and DBs of Towne-ΔUL25 compared with the respective particles from the parental Towne strain. To investigate if that was due to reduced levels of pUL26 in Towne-ΔUL25-infected cells, immunoblot analyses were carried out. As pUL26 is expressed in two isoforms, two bands related to pUL26-p27 and pUL26-p21 became apparent. The levels of pUL26-p27 were clearly reduced in Towne-ΔUL25-infected cells. Those of pUL26-p21 were also affected, but to lower levels (Fig. 5A and B). Interestingly, the levels of pUL26-p21 and pUL26-p27 were also markedly reduced in cells infected with a pp65 (pUL83) deletion mutant (Fig. 5C and D). This indicated that either pUL26 synthesis or pUL26 stability was influenced by the absence of both pUL25 and pp65.

FIG 5.

Immunoblot analysis of steady-state levels of pUL26 in infected cells. HFF cells were infected with Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne (A, B) or with Δpp65 or Towne (C, D) at an MOI of 1 (IE1 staining). After 6 days, cells were collected, lysed, and submitted to SDS-PAGE. (A, C) After transfer to PVDF membranes, immunoblot analysis was performed using antibodies against pUL26 and alpha-tubulin. (B, D) The levels of UL26 were quantified by measuring signal intensities with an ECL scanner, using Lab and Fiji ImageJ software for analysis. Tubulin was used as an internal reference. The images show one representative result out of three biological replicates.

Both pUL25 and pp65 promote pUL26 protein stability.

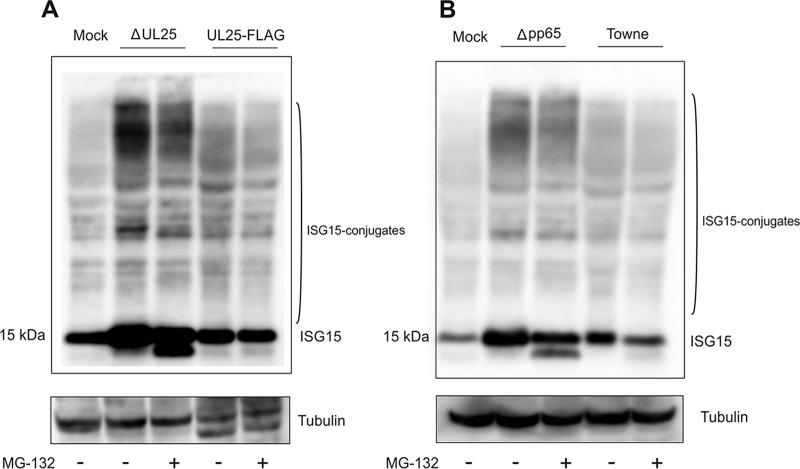

To investigate, if pUL26 protein stability was influenced by the presence of pUL25, cells were infected with Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne-UL25-FLAG. The proteasomal inhibitor MG132 was added to some samples at 6 days postinfection (dpi). Cells were collected after an additional 16 h of incubation. Cell lysates were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western blot analysis, using a pUL26-specific antibody. The levels of pUL26 were compared to those of tubulin, used as an internal control. The results showed that both known isoforms of pUL26 were reduced in Towne-ΔUL25-infected cells and that pUL26-p27 in particular was stabilized in cells treated with MG132 (Fig. 6A and B). This showed that pUL25 influenced the metabolic stability of pUL26. As a control, a comparable experiment was carried out by replacing Towne-ΔUL25 by a strain that does not express pp65 (pUL83). pUL26 levels were also reduced in pp65-negative cells, indicating that pp65 contributed to the metabolic stability of pUL26 (Fig. 6C and D).

FIG 6.

Immunoblot analysis of pUL26 degradation in the absence of pUL25 or pp65. (A) HFF cells were infected with Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne-UL25-FLAG at an MOI of 1 (IE1 staining). (C) HFF cells were infected with Towne-Δpp65 or with Towne. After 6 days, some samples were treated with MG132 for 16 h, and whole-cell lysates were subsequently collected. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses were performed. Membranes were probed with pUL26- or FLAG tag-specific antibodies (A) or with pUL26- or pp65-specific antibodies (C). (B, D) The protein levels of pUL26 were quantified by measuring the signal intensities with an ECL scanner, using Lab and Fiji ImageJ software for analysis. Tubulin was used as an internal reference. Pictures show one representative result out of two biological replicates.

pUL25 interacts with pUL26 in HCMV-infected cells.

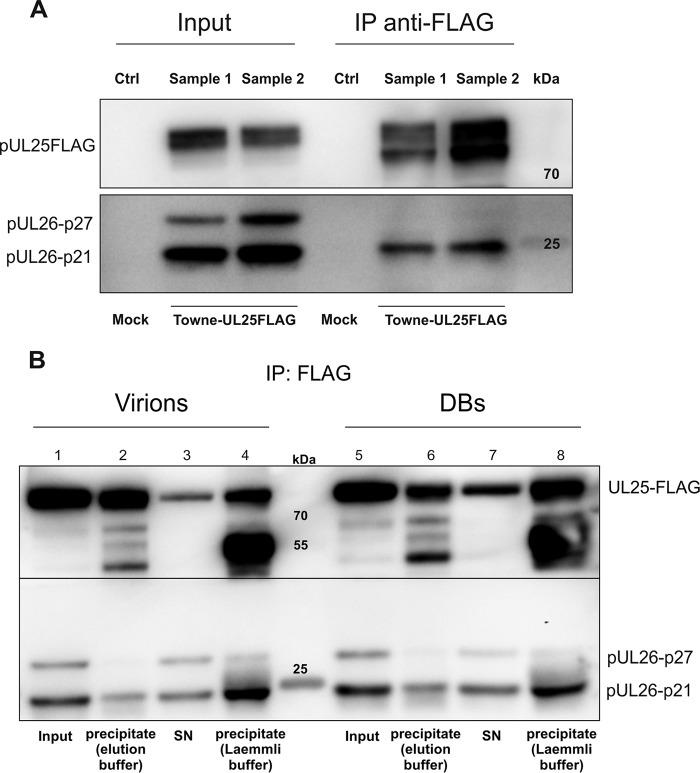

To investigate if the impact of pUL25 on pUL26 stability was related to an interaction of the two proteins, coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) analyses were performed. Cells were infected with a Towne mutant that expressed a FLAG tagged version of pUL25 (Towne-UL25-FLAG). Cell lysates were collected at 6 dpi and were subjected to co-IP, using the FLAG tag-specific antibody M2 (Fig. 7A). Using two biological replicates (samples 1 and 2), the experiments showed that pUL26 coimmunoprecipitated with pUL25, indicating that both proteins formed a complex in infected cells. To investigate if pUL25 also interacted with pUL26 in extracellular virions and DBs, co-IP experiments were repeated on purified viral particles. Again, pUL26 could be precipitated, using the pUL25-FLAG-specific antibody M2 (Fig. 7B). Taken together, the results showed that pUL25 forms a complex with pUL26, thereby stabilizing the latter protein, and that this complex is subsequently packaged into the tegument of HCMV virions as well as into DBs.

FIG 7.

Analysis of pUL25 interaction with pUL26. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged pUL25 of two independent biological replicates (samples 1 and 2). HFF were infected with Towne-UL25-FLAG at an MOI of 1 (IE1 staining) and were harvested after 6 days. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG-conjugated magnetic beads, and the precipitates were analyzed in a Western blot, probed with anti-FLAG and anti-UL26 antibodies. Uninfected HFF served as a negative control (Mock). (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged pUL25 of purified viral particles. Virions and DBs were purified as described in Materials and Methods, lysed, and analyzed in a Western blot. Lanes 1 and 5 refer to the amount of UL25-FLAG and UL26 present in the obtained lysates (Input). UL25-FLAG was then precipitated using anti-FLAG-conjugated magnetic beads. Precipitates were analyzed by use of a Western blot, probed with anti-FLAG and anti-UL26 antibodies. Lanes 2 and 6 display the coprecipitates of UL25-FLAG and UL26 after incubation with anti-FLAG magnetic beads and elution with 1 M glycine, pH 2.5. The supernatant (SN) shows the amounts of UL25-FLAG and UL26 that were not bound by anti-FLAG magnetic beads (lanes 3 and 5) as well as precipitates that were not eluted by glycine but that were eluted using Laemmli buffer (lanes 4 and 8).

ISGylation of proteins and levels of free ISG15 increase in the absence of pUL25 or pp65.

Interferons are essential for the innate immune response to virus infections. They trigger the transcription of dozens of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), whose protein products exhibit antiviral activity. Interferon-stimulated gene 15 encodes a ubiquitin-like protein (ISG15) which is induced by type I IFNs. Protein modification by ISG15 (ISGylation) is known to inhibit the replication of many viruses (23). HCMV-induced ISG15 accumulation is triggered by the hosts’ detection of cytoplasmic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). A recent report showed that pUL26 interfered with the ISGylation of proteins in HCMV-infected cells (16). To investigate if deletion of UL25 had an impact on the HCMV-induced repression of ISGylation, cells were infected for 6 days with Towne-ΔUL25 and Towne-UL25-FLAG. In some instances, MG132 was added 16 h prior to sampling. Cell lysates were subsequently subjected to Western blot analysis. Tubulin served as an internal control (Fig. 8A). Both ISG15 expression and ISGylation were indeed repressed following Towne-UL25-FLAG infection (control). This repression was alleviated following infection with Towne-ΔUL25. These results show that pUL25 is involved in suppression of ISG15 expression and ISGylation in HCMV-infected cells.

FIG 8.

Interferon-stimulated gene 15 protein (ISG15) expression and ISGylation in infected cells. (A) HFF cells were infected with Towne-ΔUL25 or Towne-UL25-FLAG at an MOI of 1 (IE1 staining). After 6 days, some samples were treated with 10 µM MG132 for 16 h and whole-cell lysates were subsequently collected. SDS-PAGE was performed, and the Western blot was probed against an ISG15 antibody. (B) HFF cells were infected with Towne-Δpp65 or Towne and were treated and processed as outlined in the legend to panel A. Free ISG15 and ISGylated proteins are indicated. The prominent band below the full-length ISG15 band likely represents an intermediate during proteasomal degradation that is stabilized by MG132 treatment. The results are those of one representative experiment out of two biological replicates.

To investigate if pp65 had a similar impact, the experiments were repeated, this time using a pp65-negative strain for infection. Again, the levels of both free ISG15 and protein ISGylation were enhanced in Δpp65-infected cells (Fig. 8B). This indicates that pp65 is also involved in the suppression of the ISG15-mediated repression of viral infection.

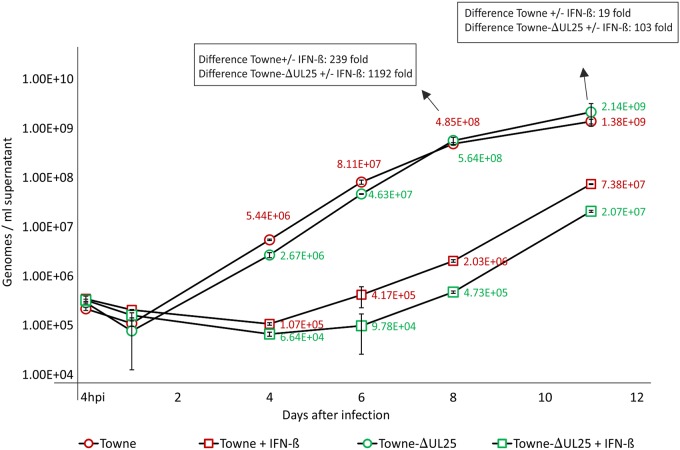

Deletion of UL25 renders HCMV replication more sensitive to IFN-β.

HCMV infection leads to the induction of ISG15 expression and enhances overall protein ISGylation in cell culture (16, 27). pUL26 has been reported to be involved in suppressing ISGylation, leading to enhanced viral replication. The level of ISGylation in cells infected with a pUL26 deletion mutant of HCMV was pronounced, and this virus was more susceptible to the addition of IFN-β to infected cultures (16). To test if a virus strain deficient in the expression of pUL25 was also more susceptible to IFN-β, cells were infected with Towne-ΔUL25 and Towne. Samples of culture supernatants were collected at different time points after infection. The levels of viral genomes in these samples, representing the release of progeny virus, were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 9). The experiments showed that Towne-ΔUL25 was clearly more susceptible to IFN-β treatment than the Towne wild-type (wt) strain.

FIG 9.

Release of viral genomes from HFF infected with Towne or Towne-ΔUL25 in the presence or absence of IFN-β. HFF were infected with the different strains in a way in which roughly equal genome copy numbers were present at the beginning of the infection (measured by qPCR at 4 h postinfection). Cell culture supernatants were collected at the indicated times. The amount of viral genomes in these samples was measured by qPCR. The values in each sample are indicated in the figure, together with the relative values of reduction in cultures treated with IFN-β. All values are means for three technical replicates. The results shown represent those from one of two biological replicates.

DISCUSSION

Some of the components of the outer HCMV virion tegument are involved in antagonizing intrinsic and innate defense mechanisms of the host cell, both immediately after their delivery into cells by virions and after their de novo synthesis in the further course of infection (12–22, 28). Surprisingly little is known, however, about the sequence of events that is necessary to assemble the outer tegument containing these proteins (29). Using yeast two-hybrid and co-IP analyses, To and colleagues identified several viral interaction partners for pUL25, suggesting that pUL25 may serve as a hub for tegument assembly (30). Using this information, we initially investigated the impact of pUL25 loss on HCMV virion and DB morphogenesis. Surprisingly, a lack of pUL25 had only a limited impact on the composition of virions and DBs. Most striking was the reduction of pUL26 in both particle fractions. In contrast, the amount of pUL24 was enhanced in both virions and DBs of Towne-ΔUL25. We confirmed that this was not due to enhanced expression from the UL24 gene. This suggests that enhanced packaging of pUL24 was compensatory, caused by the lack of pUL25 and pUL26. As pUL24 was also suggested to be a hub for tegument assembly (30), compensation for pUL25/pUL26 loss by enhanced pUL24 packaging is indeed conceivable. Further analyses focusing on pUL24 are required to address this issue.

The limited impact of pUL25 loss on HCMV virion morphogenesis was not completely unexpected. The deletion of pp65, another abundant component of the virion tegument, also resulted in only moderate changes in the virion proteome (8). The formation of DBs in the absence of pUL25 was, however, surprising, as pp65 loss had abrogated DB morphogenesis (9). pUL25 is an abundant DB component second only to pp65 (Fig. 3). However, an impact of pUL25 loss either on the morphogenesis of DBs within the cell or on the yield of DBs that could be purified from infected cell culture supernatants was not seen (not shown). DBs are a promising vaccine candidate (31–35). Production of DBs depends on their purification from infected cell cultures. Thus, safety features have to be implemented in a production process to avoid adverse effects by accidental contamination of the vaccine with infectious virus. We show here that the loss of pUL25 attenuates the capabilities of HCMV immune evasion. Deletion of pUL25 from an HCMV strain used to establish a DB-based vaccine may thus provide a safety feature for production purposes.

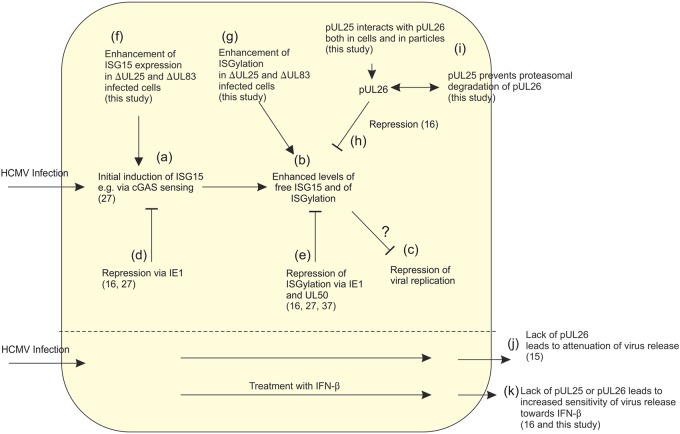

As mentioned above, the levels of pUL26 in the proteome of Towne-ΔUL25 particles were markedly reduced. pUL26 had been identified to be a viral protein that interferes with ISGylation in infected cells. ISG15 expression and ISGylation are innate defense mechanisms of the cell to battle viral infections (reviewed in references 23 and 36). As a response, viruses have developed multiple mechanisms to reduce ISG15 expression or ISGylation, or both (23, 36). For HCMV, IE1 and, more recently, pUL50 have been described, besides pUL26, to interfere with these processes (Fig. 10) (16, 27, 37). IE1 was found to reduce ISG15 expression by impairing cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS/STING (27). pUL50 was shown to interact with UBE1L, an E1-activating enzyme for ISGylation, leading to its degradation (37). pUL26 was initially identified to be a transcriptional transactivator (15). Deletion of the UL26 open reading frame resulted in a small-plaque phenotype and in impairment of particle stability (14). Mathers and colleagues later showed that pUL26 interfered with tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-κB signaling (38). Recent work indicated that pUL26 reduces the conjugation of proteins with ISG15 (16). The exact mechanisms by which pUL26 interferes with ISGylation remain unclear at this point. Interestingly, pUL26 itself is ISGylated. Mutation of ISG15 acceptor sites on pUL26 increased its intracellular levels, indicating that ISGylation of pUL26 induces its degradation (16).

FIG 10.

ISG15 expression and ISGylation during HCMV infection. (a) HCMV infection leads to the initial induction of ISG15 expression. (b) This results in an increased conjugation of cellular and viral proteins with ISG15. (c) ISG15 expression and possibly ISGylation interfere with viral reproduction by insufficiently understood mechanisms. (d) The viral IE1 protein interferes with ISG15 induction and with ISGylation. (e) In addition, pUL50 interacts with UBE1L, an E1-activating enzyme for ISGylation, leading to its degradation and thus reducing protein ISGylation. (f, g), Deletion of either UL25 or UL83 (pp65) from the viral genome results in enhanced levels of ISG15 and ISGylation in infected cells. (h) pUL26 abrogates ISG15 expression and ISGylation at later stages of HCMV infection. (i) pUL25 interacts with pUL26 in the cell and in viral particles and prevents proteasomal degradation of pUL26. (j) Deletion of UL26 leads to an attenuation of virus release. (k) The lack of both pUL25 or pUL26 results in the enhanced susceptibility of HCMV infection to IFN-β.

We show here that pUL26 is degraded in the absence of either pUL25 or pp65. The stabilization of pUL26 in the presence of MG132, a proteasomal inhibitor, indicates that pUL26 degradation in the absence of pUL25 or pp65 was mediated by the proteasome. It is, however, unclear how pUL25 and pp65 contribute to pUL26 stability. One explanation for this might be that enhanced ISGylation in Towne-ΔUL25- or Δpp65-infected cells leads to enhanced pUL26 ISGylation and degradation. This would be consistent with the data presented by Kim et al., which showed that abrogation of pUL26 ISGylation stabilized the protein (16). However, it is unclear how enhanced ISGylation in the absence of pUL25 or pp65 should specifically destabilize pUL26 while leaving other viral proteins unaltered. We could not find any evidence for an impact of pUL25 deletion on the proteomic composition of viral particles (Fig. 3). This suggests that at least other viral structural proteins were not affected in their metabolic stability in the absence of pUL25.

An alternative explanation would be that pUL25 or pp65 forms a complex with pUL26, thereby contributing to its stability. An interaction of pUL25 with pUL26 has indeed been suggested before by using yeast two-hybrid and transient transfection/co-IP approaches (30, 39). We provide proof herein that the two proteins indeed physiologically interact both in infected cells and in extracellular particles. Consequently, pUL25 binding could interfere with pUL26 ISGylation, thereby stabilizing the protein and supporting its downstream inhibitory effect on overall protein ISGylation. The investigation of that issue is the subject of further analyses.

Conflicting data on a putative pp65-pUL25 interaction, obtained using yeast two-hybrid and transfection/co-IP analysis, have been published (30, 39). In this work, we could not find evidence for a direct interaction of pp65 with pUL25, using co-IP of lysates from Towne-UL25-FLAG-infected cells (data not shown). This argues against a direct role of pp65 on pUL26 stability. Previous proteomic analyses and data from this work have, however, revealed a distinct reduction of pUL25 packaging into virions of pp65-negative HCMV strains (8, 40). It is thus likely that pp65 influences pUL25 expression or degradation in infected cells. A lack of pp65 would thus impair pUL25 expression and, indirectly, pUL26 stability and pUL26-mediated suppression of ISGylation.

A somewhat surprising finding was the enhanced expression of free ISG15 in Towne-ΔUL25-infected cells. ISG15 expression is known to be initially induced following HCMV infection but is subsequently repressed (16, 27). The HCMV IE1 protein, but not pUL26, has been identified to be one viral repressor of ISG15 expression (16, 27). We provide evidence that repression of ISG15 levels is compromised in pUL25-infected cells. This suggests that pUL25 may interfere with the IFN response at levels different from those required for its interaction with pUL26. Additional investigations will be required to address this issue.

pUL25 orthologous proteins can be found in other members of the Betaherpesvirus family (41, 42). The murine orthologue M25 has recently been investigated (41). That protein displays features that distinguish it from pUL25. It is expressed in two isoforms of 105 kDa and 130 kDa, whereas pUL25 is roughly 85 kDa. M25 can be found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, whereas pUL25 is strictly cytoplasmic (reference 24 and data not shown). Most striking is that deletion of M25 alters the cellular cytoskeleton, leading to an abrogation of MCMV-induced cell rounding, and the virion displays a reduced size (41). Neither feature was seen in our analyses of pUL25. Consequently, although there is limited sequence homology between pUL25 and M25, both proteins seem to have acquired distinct functions during adaptation to their individual host.

Taken together, we could show that pUL25 regulates pUL26 degradation and the pUL26-dependent reduction of ISGylation. Consequently, we hypothesize that pUL25 supports evasion of the ISG15-mediated antiviral defense against HCMV. The molecular background of that finding may be that pUL25 forms a complex with pUL26 in infected cells. Deletion of pUL25 impairs pUL26-mediated suppression of ISGylation, thereby destabilizing pUL26 itself. As a functional consequence, the replication of a UL25 deletion mutant is more sensitive to IFN-β treatment than that of a UL25-positive strain. Thus, this study adds pUL25 as another viral tegument protein that contributes to HCMV evasion of the innate response of the host cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, BAC reconstitution, and viruses.

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were cultured as described before (43). The following strains were used in this study: Towne-BAC (44), kindly provided by Edward Mocarski, Hua Zhu, and Fenyong Liu, herein termed Towne; BADwt (45), kindly provided by Thomas Shenk; TB40/E-BAC4 (46), kindly provided by Christian Sinzger, herein termed TB40; TB40-UL83 Stop (47), kindly provided by Michael Nevels and Christina Paulus; and KB14 (48) and a derivative of Towne-UL130rep (49), in which the pp65 open reading frame UL83 was replaced by a kanamycin resistance cassette (Towne-Δpp65).

Virus reconstitution from BAC clones was achieved by transfection of BAC DNA into HFF. BACmid DNA for transfection was obtained from Escherichia coli using a plasmid purification kit (Machery & Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfections into HFF were performed using the SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). HFF were seeded on 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well, using different BAC DNA concentrations. Cells were subsequently passaged until plaques became visible. The infectious supernatant was then transferred to uninfected cells for passaging of the virus. All HCMV strains were propagated on HFF. Viral stocks were obtained by collecting the culture supernatants from infected HFF, followed by low-speed centrifugation to remove cell debris. Supernatants were frozen at −80°C until further use.

Virus titers were determined either by quantitation of the viral genomes in cell culture supernatants (see below) or by counting of the IE1-positive cells (49).

Generation of HCMV strains Towne-ΔUL25 and Towne-UL25-FLAG.

The HCMV Towne strain represented the backbone on which the Towne-ΔUL25 and Towne-UL25-FLAG strains were generated (44). Strain Towne-ΔUL25 was generated by inserting the gene encoding the bacterial galactokinase (galK) into the UL25 open reading frame of Towne, using the procedure described by Warming et al. (50). By doing this, the UL25 open reading frame was replaced by the galK cassette starting with base pair 288, thereby disrupting pUL25 expression. The 5′ 287 nucleotides were included to preserve the putative promoter of the adjacent UL24 open reading frame. The resulting construct was denominated Towne-ΔUL25-BAC. After transfection of Towne-ΔUL25-BAC into fibroblasts, the virus Towne-ΔUL25 was reconstituted. To generate the revertant virus Towne-UL25-FLAG, a gene fragment encoding the FLAG tag epitope (DYKDDDDK) was inserted at the 3′ end of the UL25 open reading frame, using Towne-ΔUL25-BAC as a template and the galK procedure for selection (50). The resulting BAC clone, Towne-UL25-FLAG-BAC, was reconstituted by transfecting its DNA into fibroblasts, generating the virus Towne-UL25-FLAG. The recombinant virus expressed pUL25 with a FLAG tag attached to the carboxy terminus of the protein. Generation of a viral master stock was performed as detailed in the previous section.

Northern blot analysis.

Northern blot analyses were performed as described previously (51). Briefly, cells were infected at an MOI of 5 (IE1 titration) for RNA preparation. The RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Northern blot analyses were performed according to the instructions in the manufacturer’s manual (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). For electrophoresis, 10 µg of RNA was loaded on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel supplemented with 0.65% (wt/vol) formaldehyde. RNA was transferred to nylon membranes (Roche Diagnostics) and probed with digoxigenin-dUTP-labeled DNA probes specific for UL24 or GAPDH. The UL24 probe was generated by PCR using forward primer 5′-CGCGTCACATGAGCGATCTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GTGGCGGATGATGAATCG-3′. The GAPDH probe was generated using forward primer 5′-GCTTCACCACCTTCTTGATG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TGGAGTCTACTGGTGTCTTC-3′.

Virion and DB purification.

DBs were produced in human fibroblast cells upon infection with a recombinant HCMV seed virus. This seed virus was obtained upon transfection of cells with a BAC plasmid carrying a genetically modified version of the genome of the HCMV Towne strain. For particle purification, 1.8 × 106 primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were grown in 20 175-cm2 tissue culture flasks in minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco-BRL, Glasgow, Scotland) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), l-glutamine (100 mg/liter), and gentamicin (50 mg/liter) for 1 day. The cells were infected with 0.5 ml of frozen stocks of human cytomegalovirus strains. The virus inoculum was allowed to adsorb for 1.5 h at 37°C. The cells were incubated for at least 7 days. When the cells showed a cytopathic effect (CPE) of late HCMV infection (usually at day 7 postinfection [p.i.]), the supernatant was harvested and centrifuged for 10 min at 1,475 × g to remove cellular debris. After that, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 95,000 × g (70 min, 10°C) in either a SW32Ti swing-out rotor or a 45Ti rotor in a Beckman Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge. The pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Glycerol tartrate gradients were prepared immediately before use. For this, 4 ml of a 35% Na-tartrate solution in 0.04 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, was applied to one column, and 5 ml of a 15% Na-tartrate–30% glycerol solution in 0.04 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, was applied to the second column of a gradient mixer. The gradients were prepared by slowly dropping the solutions into Beckman Ultra-Clear centrifuge tubes (14 by 89 mm), positioned at an angle of 45°. One milliliter of the viral particles was then carefully layered on top of the gradients. Ultracentrifugation was performed without braking in a Beckman SW41Ti swing-out rotor for 60 min at 90,000 × g and 10°C. The particles were illuminated by light scattering and were collected from the gradient by penetrating the centrifuge tube with a hollow needle below the band. Samples were carefully drawn from the tube with a syringe.

The particles were washed with 1× PBS and pelleted in an SW41Ti swing-out rotor for 90 min at 98,000 × g and 10°C. After the last centrifugation step, the DBs were resuspended in 250 µl to 350 µl 1× PBS and the virions were resuspended in 120 to 150 µl 1× PBS and stored at –80°C. The protein concentration of the purified DBs and virions was determined with a Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Bonn, Germany).

Preparation of samples for TEM.

Two flasks of HFF (1.74 million cells per flask) were infected at an MOI of 0.8. Cells were incubated for 6 days and were subsequently detached from the support using trypsin. The cells from the two flasks were pooled and centrifuged at 270 × g. Cells were then fixed by adding 1 ml fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 0.1 M sucrose) and resuspending the cells carefully. Following a centrifugation step for 5 min at 270 × g, the cell pellet was again resuspended in 1 ml fixative. The cells were subsequently incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then again centrifuged for 5 min at 270 × g. The cells were then resuspended in washing buffer (0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 0.1 M sucrose) and centrifuged. The procedure was repeated twice. After the final washing step, the cells were not centrifuged but were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were then transferred in Eppendorf tubes. Samples were then further processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as previously described and analyzed in an FEI Tecnai 12 Omega electron microscope (49).

IFN-β treatment.

Subconfluent HFF cells were treated with IFN-β (100 U/ml diluted in 0.1% bovine serum albumin–double-distilled H2O; specific activity, according to the manufacturer’s information, 5 × 108 U/mg; catalog number 300-02BC; PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany). After 12 h of incubation, the cells were infected with Towne or Towne-ΔUL25 at an MOI of 0.05. Infected cells, kept in the absence of IFN-β, served as a control. DNA out of 200 µl cell culture supernatant or from 105 infected cells was isolated using a High Pure viral nucleic acid kit from Roche according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was finally eluted in 50 to 100 µl elution buffer and subjected to TaqMan analysis.

Analysis of genome replication kinetics.

HFF (2 × 105) were seeded in each 30-cm2 culture dish. Five milliliters of the appropriate culture medium was added. Incubation was overnight at 37°C under humid conditions. On the following day, cells were infected with the different HCMV strains at an MOI of 0.05. At 1.5 h after the addition of virus, the inoculum was removed. One dish each was taken at 4 h after infection to normalize the amount of DNA that had entered the cells. The cells of these dishes were washed with 1× PBS, detached from the dish by trypsin, centrifuged, counted, and adjusted to 1 × 106/ml with 1 × PBS. The residual cells in the dishes were then cultured for various times until sample collection, as denoted above. Samples were stored at −20°C until further use. The DNA contained in 100 µl (1 × 105 cells) of each cell suspension sample was extracted using the High Pure viral nucleic acid kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of viral DNA was performed using an ABI 7500 Fast real-time PCR detection system. Results were calculated as the number of genome copies per cell.

DNA quantification.

For the TaqMan assay, the reaction mixture consisted of 45 µl master mix (the probe, primers, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, buffer, and Taq polymerase) and 5 µl DNA per sample. Analyses were performed in triplicate technical replicates with the probe 5'-6FAM-CCACTTTGCCGATGTAACGTTTCTTGCAT-TMR (where 6FAM is 6-carboxyfluorescein and TMR is tetramethylrhodamine), forward primer 5′-TCATCTACGGGGACACGGAC-3′, reverse primer 5′-TGCGCACCAGATCCACG-3′, HotStar Taq Plus Taq polymerase from Qiagen, and a standard dilution of cosmid pCM1049 (52). The TaqMan program was 95°C for 5 min and 42 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

HFF were infected with the respective HCMV strains. Infected HFF cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in lysis buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 0.05 M Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, 10 mM dithiothreitol). Cell lysates were sonicated (once for 10 s at 30% output; Branson Sonifier 250), and proteins were subsequently bound to specific antibodies (anti-FLAG M2; Sigma) overnight at 4°C in a rotator. Antibody-protein complexes were then collected by IgG magnetic beads for 2 h at room temperature. The magnetic beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer and subsequently resuspended with dilution buffer (1 M glycine, pH 2.5) and/or Laemmli sample buffer. Protein samples were loaded on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The filters were probed with specific primary antibodies. Quantitative analyses were performed by using tubulin as an internal standard. For this, an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection substrate (Best Western Femto; Thermo Fisher) and a ChemiDoc scanner (Bio-Rad) were used.

Proteasome inhibition.

To investigate the proteasomal degradation of individual proteins, HFF cells were infected at an MOI of 1. At 6 dpi, the cells were treated with 10 µM MG132 proteasome inhibitor (Sigma) for 16 h. The cells were then harvested and lysed, and the levels of UL26 were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis.

Aliquots (20 μg) of purified virions were dissolved in lysis buffer. Lysis buffer consisted of 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS). Subsequently, the proteins were digested by trypsin using a modified filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) method (53). Before liquid chromatography (LC)-MS analysis, the resulting tryptic peptides were spiked with 25 fmol/μl of enolase 1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) tryptic digest standard (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Nanoscale LC separation of tryptic peptides was performed with a nanoAcquity system (Waters) equipped with an HSS-T3 75-μm by 250-mm analytical reversed-phase column (particle size, 1.8 μm; Waters) in direct-injection mode, as described previously (53). Mobile phases, gradients, and flow rates were chosen as described elsewhere (53). Two hundred nanograms of total protein was injected per technical replicate.

Mass spectrometric analysis of tryptic peptides was performed using data-independent acquisition (53) in three replicates using a Synapt G2-S mass spectrometer (Waters) with a typical resolution of at least 25,000 full-width half maximum (FWHM). All analyses were performed in the positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode using the instrument settings and nanoLock spray calibration described previously (48). The obtained continuum LC-MS data were processed and searched using the ProteinLynx global server (PLGS), version 3.0.2 (Waters). Protein identifications were obtained by searching a custom-compiled database containing sequences of human and HCMV proteins from the UniProt database. Sequence information for enolase 1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and bovine trypsin was added to the databases. For the database search, we allowed a 3-ppm precursor and 10-ppm product ion tolerance with one missed cleavage and fixed carbamidomethyl cysteine and a variable methionine oxidation set as the modifications. For valid protein identification, the following criteria had to be met: at least two peptides had to be detected, and together they had to have at least seven fragment ions. The false-positive rate for protein identification was set to 1%, based on a search of a reversed decoy database. For the absolute quantification of virion proteins, we employed a well-established label-free quantitative proteomics work flow using the quantification value for spiked yeast enolase 1 as a reference. Values were normalized across technical replicates and samples using the ISOQuant software tool (8, 53).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the donation of monoclonal antibodies by William Britt and Thomas Stamminger. We are grateful for receiving viruses and BAC clones from Hua Zhu, Fenyong Liu, Edward Mocarski, Thomas Shenk, Christian Sinzger, Michael Nevels, and Christina Paulus.

The work was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, individual project PL236/7-1 (to B.P.), and the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (to B.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffiths PD, Reeves M. 2017. Cytomegalovirus, p 481–510. In Richman D, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG (ed), Clinical virology, 4th ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu X, Shah S, Lee M, Dai W, Lo P, Britt W, Zhu H, Liu F, Zhou ZH. 2011. Biochemical and structural characterization of the capsid-bound tegument proteins of human cytomegalovirus. J Struct Biol 174:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai X, Yu X, Gong H, Jiang X, Abenes G, Liu H, Shivakoti S, Britt WJ, Zhu H, Liu F, Zhou ZH. 2013. The smallest capsid protein mediates binding of the essential tegument protein pp150 to stabilize DNA-containing capsids in human cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003525. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Griffiths PD, Pass RF. 2013. Cytomegaloviruses, p 1960–2014. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irmiere A, Gibson W. 1983. Isolation and characterization of a noninfectious virion-like particle released from cells infected with human strains of cytomegalovirus. Virology 130:118–133. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varnum SM, Streblow DN, Monroe ME, Smith P, Auberry KJ, Pasa-Tolic L, Wang D, Camp DG, Rodland K, Wiley S, Britt W, Shenk T, Smith RD, Nelson JA. 2004. Identification of proteins in human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) particles: the HCMV proteome. J Virol 78:10960–10966. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10960-10966.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roby C, Gibson W. 1986. Characterization of phosphoproteins and protein kinase activity of virions, noninfectious enveloped particles, and dense bodies of human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 59:714–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyda S, Tenzer S, Navarro P, Gebauer W, Saur M, Krauter S, Buscher N, Plachter B. 2014. The tegument protein pp65 of human cytomegalovirus acts as an optional scaffold protein that optimizes protein uploading into viral particles. J Virol 88:9633–9646. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01415-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmolke S, Kern HF, Drescher P, Jahn G, Plachter B. 1995. The dominant phosphoprotein pp65 (UL83) of human cytomegalovirus is dispensable for growth in cell culture. J Virol 69:5959–5968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn W, Chou C, Li H, Hai R, Patterson D, Stolc V, Zhu H, Liu F. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:14223–14228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334032100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becke S, Fabre-Mersseman V, Aue S, Auerochs S, Sedmak T, Wolfrum U, Strand D, Marschall M, Plachter B, Reyda S. 2010. Modification of the major tegument protein pp65 of human cytomegalovirus inhibits virus growth and leads to the enhancement of a protein complex with pUL69 and pUL97 in infected cells. J Gen Virol 91:2531–2541. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalejta RF. 2013. Pre-immediate early tegument protein functions, p 141–151. In Reddehase MJ. (ed), Cytomegaloviruses: from molecular pathogenesis to intervention, 2nd ed Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biolatti M, Dell'Oste V, De Andrea M, Landolfo S. 2018. The human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp65 (pUL83): a key player in innate immune evasion. New Microbiol 41:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorz K, Hofmann H, Berndt A, Tavalai N, Mueller R, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Stamminger T. 2006. Deletion of open reading frame UL26 from the human cytomegalovirus genome results in reduced viral growth, which involves impaired stability of viral particles. J Virol 80:5423–5434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02585-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamminger T, Gstaiger M, Weinzierl K, Lorz K, Winkler M, Schaffner W. 2002. Open reading frame UL26 of human cytomegalovirus encodes a novel tegument protein that contains a strong transcriptional activation domain. J Virol 76:4836–4847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4836-4847.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YJ, Kim ET, Kim YE, Lee MK, Kwon KM, Kim KI, Stamminger T, Ahn JH. 2016. Consecutive inhibition of ISG15 expression and ISGylation by cytomegalovirus regulators. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schierling K, Buser C, Mertens T, Winkler M. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein ppUL35 is important for viral replication and particle formation. J Virol 79:3084–3096. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3084-3096.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalejta RF, Bechtel JT, Shenk T. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression by inducing the proteasome-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors. Mol Cell Biol 23:1885–1895. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.1885-1895.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann H, Sindre H, Stamminger T. 2002. Functional interaction between the pp71 protein of human cytomegalovirus and the PML-interacting protein human Daxx. J Virol 76:5769–5783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5769-5783.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marschall M, Feichtinger S, Milbradt J. 2011. Regulatory roles of protein kinases in cytomegalovirus replication. Adv Virus Res 80:69–101. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385987-7.00004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Chen J, Cristea IM. 2013. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pUL83 inhibits IFI16-mediated DNA sensing for immune evasion. Cell Host Microbe 14:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cristea IM, Moorman NJ, Terhune SS, Cuevas CD, O'Keefe ES, Rout MP, Chait BT, Shenk T. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus pUL83 stimulates activity of the viral immediate-early promoter through its interaction with the cellular IFI16 protein. J Virol 84:7803–7814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00139-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villarroya-Beltri C, Guerra S, Sanchez-Madrid F. 2017. ISGylation—a key to lock the cell gates for preventing the spread of threats. J Cell Sci 130:2961–2969. doi: 10.1242/jcs.205468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battista MC, Bergamini G, Boccuni MC, Campanini F, Ripalti A, Landini MP. 1999. Expression and characterization of a novel structural protein of human cytomegalovirus, pUL25. J Virol 73:3800–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zini N, Battista MC, Santi S, Riccio M, Bergamini G, Landini MP, Maraldi NM. 1999. The novel structural protein of human cytomegalovirus, pUL25, is localized in the viral tegument. J Virol 73:6073–6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldick CJ Jr, Shenk T. 1996. Proteins associated with purified human cytomegalovirus particles. J Virol 70:6097–6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bianco C, Mohr I. 2017. Restriction of human cytomegalovirus replication by ISG15, a host effector regulated by cGAS-STING double-stranded-DNA sensing. J Virol 91:e02483-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02483-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. 2006. Inactivating a cellular intrinsic immune defense mediated by Daxx is the mechanism through which the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein stimulates viral immediate-early gene expression. J Virol 80:3863–3871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3863-3871.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith RM, Kosuri S, Kerry JA. 2014. Role of human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins in virion assembly. Viruses 6:582–605. doi: 10.3390/v6020582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To A, Bai Y, Shen A, Gong H, Umamoto S, Lu S, Liu F. 2011. Yeast two hybrid analyses reveal novel binary interactions between human cytomegalovirus-encoded virion proteins. PLoS One 6:e17796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepperl S, Münster J, Mach M, Harris JR, Plachter B. 2000. Dense bodies of human cytomegalovirus induce both humoral and cellular immune responses in the absence of viral gene expression. J Virol 74:6132–6146. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.13.6132-6146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mersseman V, Böhm V, Holtappels R, Deegen P, Wolfrum U, Plachter B, Reyda S. 2008. Refinement of strategies for the development of a human cytomegalovirus dense body vaccine. Med Microbiol Immunol 197:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s00430-008-0085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becke S, Aue S, Thomas D, Schader S, Podlech J, Bopp T, Sedmak T, Wolfrum U, Plachter B, Reyda S. 2010. Optimized recombinant dense bodies of human cytomegalovirus efficiently prime virus specific lymphocytes and neutralizing antibodies without the addition of adjuvant. Vaccine 28:6191–6198. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider-Ohrum K, Cayatte C, Liu Y, Wang Z, Irrinki A, Cataniag F, Nguyen N, Lambert S, Liu H, Aslam S, Duke G, McCarthy MP, McCormick L. 2016. Production of cytomegalovirus dense bodies by scalable bioprocess methods maintains immunogenicity and improves neutralizing antibody titers. J Virol 90:10133–10144. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00463-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cayatte C, Schneider-Ohrum K, Wang Z, Irrinki A, Nguyen N, Lu J, Nelson C, Servat E, Gemmell L, Citkowicz A, Liu Y, Hayes G, Woo J, Van Nest G, Jin H, Duke G, McCormick AL. 2013. Cytomegalovirus vaccine strain Towne-derived dense bodies induce broad cellular immune responses and neutralizing antibodies that prevent infection of fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J Virol 87:11107–11120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01554-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perng YC, Lenschow DJ. 2018. ISG15 in antiviral immunity and beyond. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:423–439. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee MK, Kim YJ, Kim YE, Han TH, Milbradt J, Marschall M, Ahn JH. 2018. Transmembrane protein pUL50 of human cytomegalovirus inhibits ISGylation by downregulating UBE1L. J Virol 91:e00462-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00462-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathers C, Schafer X, Martinez-Sobrido L, Munger J. 2014. The human cytomegalovirus UL26 protein antagonizes NF-kappaB activation. J Virol 88:14289–14300. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02552-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips SL, Bresnahan WA. 2011. Identification of binary interactions between human cytomegalovirus virion proteins. J Virol 85:440–447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01551-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reyda S, Buscher N, Tenzer S, Plachter B. 2014. Proteomic analyses of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169 derivatives reveal highly conserved patterns of viral and cellular proteins in infected fibroblasts. Viruses 6:172–188. doi: 10.3390/v6010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutle I, Sengstake S, Templin C, Glass M, Kubsch T, Keyser KA, Binz A, Bauerfeind R, Sodeik B, Cicin-Sain L, Dezeljin M, Messerle M. 2017. The M25 gene products are critical for the cytopathic effect of mouse cytomegalovirus. Sci Rep 7:15588. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15783-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang B, Nishimura M, Tang H, Kawabata A, Mahmoud NF, Khanlari Z, Hamada D, Tsuruta H, Mori Y. 2016. Crystal structure of human herpesvirus 6B tegument protein U14. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005594. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Besold K, Wills M, Plachter B. 2009. Immune evasion proteins gpUS2 and gpUS11 of human cytomegalovirus incompletely protect infected cells from CD8 T cell recognition. Virology 391:5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marchini A, Liu H, Zhu H. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus with IE-2 (UL122) deleted fails to express early lytic genes. J Virol 75:1870–1878. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1870-1878.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu D, Smith GA, Enquist LW, Shenk T. 2002. Construction of a self-excisable bacterial artificial chromosome containing the human cytomegalovirus genome and mutagenesis of the diploid TRL/IRL13 gene. J Virol 76:2316–2328. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2316-2328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinzger C, Hahn G, Digel M, Katona R, Sampaio KL, Messerle M, Hengel H, Koszinowski U, Brune W, Adler B. 2008. Cloning and sequencing of a highly productive, endotheliotropic virus strain derived from human cytomegalovirus TB40/E. J Gen Virol 89:359–368. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Büscher N, Paulus C, Nevels M, Tenzer S, Plachter B. 2015. The proteome of human cytomegalovirus virions and dense bodies is conserved across different strains. Med Microbiol Immunol 204:285–293. doi: 10.1007/s00430-015-0397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hesse J, Reyda S, Tenzer S, Besold K, Reuter N, Krauter S, Büscher N, Stamminger T, Plachter B. 2013. Human cytomegalovirus pp71 stimulates major histocompatibility complex class I presentation of IE1-derived peptides at immediate early times of infection. J Virol 87:5229–5238. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03484-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krömmelbein N, Wiebusch L, Schiedner G, Büscher N, Sauer C, Florin L, Sehn E, Wolfrum U, Plachter B. 2016. Adenovirus E1A/E1B transformed amniotic fluid cells support human cytomegalovirus replication. Viruses 8:37. doi: 10.3390/v8020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. 2005. Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res 33:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hesse J, Ameres S, Besold K, Krauter S, Moosmann A, Plachter B. 2013. Suppression of CD8+ T-cell recognition in the immediate-early phase of human cytomegalovirus infection. J Gen Virol 94:376–386. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.045682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleckenstein B, Müller I, Collins J. 1982. Cloning of the complete human cytomegalovirus genome in cosmids. Gene 18:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Distler U, Kuharev J, Navarro P, Levin Y, Schild H, Tenzer S. 2014. Drift time-specific collision energies enable deep-coverage data-independent acquisition proteomics. Nat Methods 11:167–170. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]