Abstract

Objective

To compare age standardised death rates for respiratory disease mortality between the United Kingdom and other countries with similar health system performance.

Design

Observational study.

Setting

World Health Organization Mortality Database, 1985-2015.

Participants

Residents of the UK, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Australia, Canada, the United States, and Norway (also known as EU15+ countries).

Main outcome measures

Mortality from all respiratory disease and infectious, neoplastic, interstitial, obstructive, and other respiratory disease. Differences between countries were tested over time by mixed effect regression models, and trends in subcategories of respiratory related diseases assessed by a locally weighted scatter plot smoother.

Results

Between 1985 and 2015, overall mortality from respiratory disease in the UK and EU15+ countries decreased for men and remained static for women. In the UK, the age standardised death rate (deaths per 100 000 people) for respiratory disease mortality in the UK fell from 151 to 89 for men and changed from 67 to 68 for women. In EU15+ countries, the corresponding changes were from 108 to 69 for men and from 35 to 37 in women. The UK had higher mortality than most EU15+ countries for obstructive, interstitial, and infectious subcategories of respiratory disease in both men and women.

Conclusion

Mortality from overall respiratory disease was higher in the UK than in EU15+ countries between 1985 and 2015. Mortality was reduced in men, but remained the same in women. Mortality from obstructive, interstitial, and infectious respiratory disease was higher in the UK than in EU15+ countries.

Introduction

Respiratory diseases pose a large health burden across health systems and consistently rank among the most fatal diseases across developed countries.1 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory tract infections, lung cancer (including tracheal tumours), and tuberculosis have resulted in 2.9 million, 2.4 million, 1.7 million, and 1.2 million deaths, respectively in 2016.1 Poor outcomes from respiratory diseases are consistent across different health systems with lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lower respiratory tract infections being consistently leading causes of death.

The United Kingdom has previously been highlighted as an outlier with higher mortality and morbidity attributed to respiratory disease than other western countries.2 Previous analysis comparing UK mortality with western Europe, the United States, Canada, and Australia has shown that the UK ranked poorly for respiratory disease.3 When years of life lost were estimated, the UK ranked 17th of 19 for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 18th of 19 for lower respiratory tract infections.3 For less common respiratory diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the UK has also been identified as an outlier compared with other health systems with similar health related expenditure.4 Deaths from respiratory diseases are amenable to healthcare. The UK has ranked poorly in reports comparing amenable mortality in similar health systems.5 Although measuring outcomes from broad disease categories might have many explanations, this comparative approach remains valuable in assessing overall health system performance. Whether increased respiratory disease mortality in the UK is attributable to smoking, pollution, other environmental factors, or to the delivery of healthcare, requires further evaluation and validation with an independent dataset.

Our primary aim was to compare the trends in mortality from respiratory disease in the UK with Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Australia, Canada, the US, and Norway (also known as the European Union (EU)15+ countries). We performed an observational analysis of the World Health Organization Mortality Database to compare death rates from primary respiratory diseases. We have previously used data from the WHO Mortality Database to assess changes in trends from cardiovascular and cancer mortality,6 and used similar trend analysis to assess UK regional variation in cancer mortality.7 In the current analysis, we have used an independent dataset and longitudinal data to assess trends over a long observation period.3

Methods

Data sources

For this analysis of national registry data, we defined comparator countries as the EU15+ countries (excluding the UK). Previous reports have used the EU15+ countries as an appropriate comparator group for health issues in the UK because of similar or higher health expenditure in these countries.8 This group of countries included the EU member states before May 2004, not including the UK (that is, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden), as well as Australia, Canada, the US, and Norway.

We obtained data for respiratory disease mortality for the countries of interest from the WHO Mortality Database.9 The database contains country level data for deaths by age, sex, and cause of death from 1955 onwards, as reported annually by WHO member states from their local death registration systems. Data are reported as crude mortality in each country per year. For each country and year, we grouped data within the age groups provided by the World Standard Population, stratified by sex. We then calculated age standardised death rates per 100 000 people in the specific age group by using population data and the World Standard Population.10 We included data from 1985 to 2015 as these were the most recent data available for most countries. Almost complete data were available for each country studied with a total of 30 of 570 (5%) missing data elements across all countries over the observation period.

Diagnostic categories

We included the following ICD (international classification of diseases) categories of respiratory diseases: infectious (including respiratory tuberculosis, influenza, and viral and bacterial pneumonias), neoplastic (including malignancy of trachea, bronchus, lung, and pleura), interstitial (including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and unspecified interstitial lung diseases), obstructive (including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiectasis), and other (including pneumothorax, pulmonary oedema, and other unspecified respiratory disorders). A list of the ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (9th and 10th revisions, respectively) used in this analysis is provided in supplementary table 1. We used both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for overall respiratory disease covering the period 1985 to 2015. We used ICD-10 codes for the analysis of subcategories of respiratory disease covering the period 2001 to 2015. This was decided a priori to prevent introduction of discrepancies through coding changes.

Statistical analysis

We computed age standardised death rates for respiratory disease mortality in the UK and computed the median composite age standardised death rate in the remaining EU15+ countries. We tested for significant differences between the UK and EU15+ countries by using mixed effects regression models for change in mortality using the PROC GENMOD procedure in SAS version 9.4. Each model included all available data years for all countries with estimates for individual country intercepts. We constructed a model which included predictor terms: country (UK or EU15+), year, and the interaction of country with year. We used auto regression to account for within country correlations. The outcome variable was the log of mortality. The coefficient results of this model multiplied by 100 are interpreted as symmetric percentage differences.11 Significance in the models was defined as P<0.05. We used locally weighted scatter plot smoother to assess trends in mortality from overall respiratory disease as well as subcategories of respiratory diseases.

Secondly, we repeated the same modelling strategy for repeated measures by using subcategories of respiratory diseases (infectious, neoplastic, interstitial, obstructive, and other) to compare trends between the UK and EU15+ countries. Whereas our analysis of overall respiratory disease mortality assessed trends over a 30 year period by using both the ICD-9 and ICD-10 classification systems, we chose a priori to analyse the subcategories of respiratory disease mortality by using the ICD-10 classification system to ensure maximum comparability of disease coding. We grouped mortality by ICD-10 chapter. For this analysis, we computed age standardised death rates in each subcategory of respiratory disease and constructed data series plots for graphical inspection. Owing to the risk of multiple testing, we corrected using the Bonferroni method the level of significance for the five subcategories of respiratory disease, giving P<0.01 as statistically significant for the subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed one post hoc confirmatory analysis. For data deposited in the WHO Mortality Database, the preferred sources of information are death registration data, including medical certification of the cause of death and cause of death coded by using ICD categories. One possible explanation for the observed greater mortality in the UK than in EU15+ countries could include differences in medical certification and hospital discharge coding practices between comparator countries. Therefore, after completing the primary analysis to compare respiratory disease mortality, we considered the possibility that differences between health systems for death registration could contribute to the overall differences between the UK and EU15+ countries. We performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis to investigate this possibility and, for this analysis, we assessed trends in mortality for other common broad disease categories, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, as well as renal diseases, and compared age standardised death rates for each category of disease. This sensitivity analysis, therefore, compared the UK with EU15+ countries for non-respiratory diseases to consider the possibility that coding practices alone might have contributed to the observed difference in respiratory disease mortality.

Patient involvement

To better understand the direct implications of this work on patient knowledge and experience across health systems, we presented our findings to patients with a variety of chronic lung conditions from countries used in this investigation. Specifically, we circulated the results of the current investigation to a total of six patients among the network of the European Federation of Allergy and Airways Diseases Patients Associations and the European Lung Foundation: three with Bronchiectasis (two from the UK, one from the Netherlands), two with Asthma (one from the UK, one from the Netherlands), as well as one with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (from Ireland). Patients were asked to comment on the potential implications of this research as well as areas of focus for future research. Patients responded to four questions: all questions were equal to every patient although everyone responded according to their experience, their national healthcare system, and their disease. Responses from patients are summarised as a general answer (non-disease specific) in box 1.

Box 1. Patient perspectives on chronic lung diseases, possible explanations for the results of the current investigation, and areas of interest for future research work.

There is wide agreement from patients around the fact that early and correct diagnosis is vital. However, education and awareness is paramount to ensuring adequate management of chronic lung diseases as it will ensure the access to a proper treatment plan and will allow patients to adapt to a healthier lifestyle (eg, quitting smoking, improving physical activities, and avoiding environmental triggers).

Possible explanations for the differences in reported outcomes from these conditions across health systems may include different health behaviours and patient adherence to treatments rather than the medical issues themselves. Poor adherence can have many reasons: for example, side effects of medicines, forgetfulness or lack of motivation, or even opposition against a rigid treatment regimen. Adherence to treatment can be improved through awareness and health literacy; support from family, friends, and patient groups; access to specialised nurses and respiratory physiotherapists; better drugs and devices; digital health; and involving expertise in the areas of adding behaviour, learning styles, stages of change, influencing factors, and self efficacy.

Research priorities should include searching for the mechanisms underlying of lung diseases and how to repair damaged lungs as well as developing personalised medicines and new curative treatments. Other priorities include: identification of subtypes of disease, assessing the effectiveness of patients and healthcare proxy communication, avoiding exacerbations and preventing fatigue, research on microbiome and better oxygen delivery systems, as well as improving adherence, promoting patient centeredness and health literacy, especially on environmental triggers.

Results

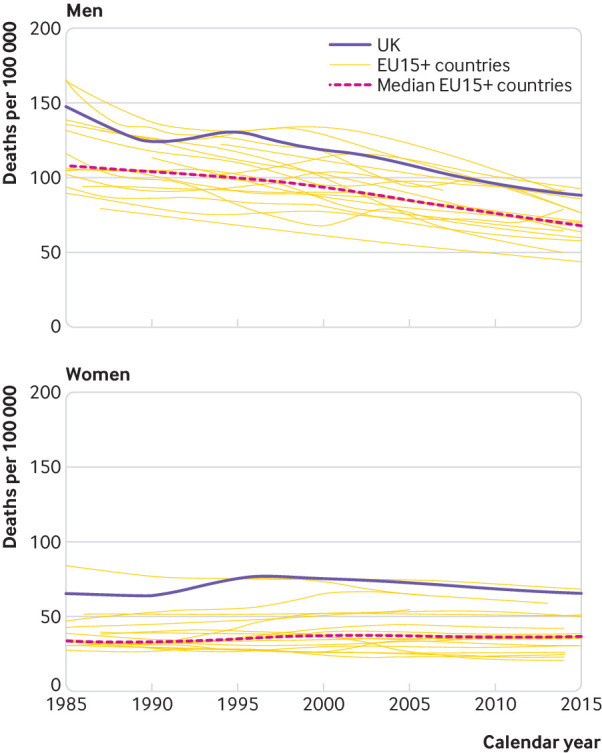

Trends in overall respiratory disease

Figure 1 shows that between 1985 and 2015, overall respiratory disease mortality in the UK and EU15+ countries decreased for men and remained static for women. In the UK, there was a slight disjunction in the overall trend with increasing rates between 1990 and 1995 in both men and women. In the UK, the age standardised death rate (number of deaths per 100 000 population) from respiratory disease decreased for men (from 151 to 89) and remained static for women (68 to 67). In EU15+ countries, the age standardised death rate from respiratory disease decreased for men (from 108 to 69) and remained static for women (35 to 37). The results of mixed effects models showed significantly higher respiratory related age standardised death rates in the UK in men and women than in most countries. In men and women, all countries except Denmark showed statistically significantly lower mortality than the UK (all P<0.05).

Fig 1.

Trend in age standardised death rates per 100 000 population

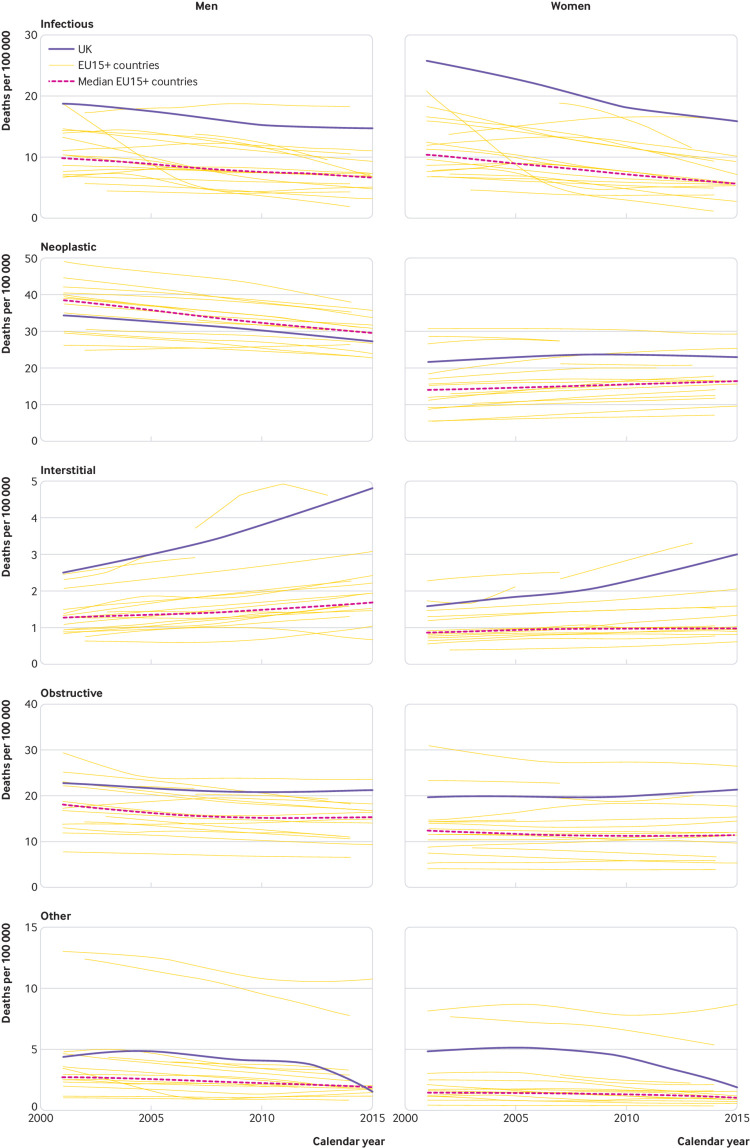

Trends in subcategories of respiratory disease

Figure 2 shows the trends for subcategories of respiratory diseases comparing the UK with EU15+ countries by sex. Infectious respiratory disease included influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis; neoplastic respiratory disease included malignancy of the bronchus, lung, and pleura; interstitial respiratory disease included idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; obstructive respiratory disease included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and bronchiectasis; and other respiratory disease included pulmonary oedema and pneumothorax. The UK was an outlier for respiratory disease mortality in women for all causes assessed. For men, the UK was an outlier for infectious, interstitial, other, and (for part of the observation period (since 2005)) obstructive respiratory disease. Except for neoplastic respiratory disease, the UK showed significantly higher age standardised death rates than EU15+ countries for subcategories of respiratory disease.

Fig 2.

Trends in age standardised death rate for subcategories of respiratory disease mortality

Post hoc sensitivity analyses

Analysis of mortality from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, over the period from 1985 to 2015, showed favourable trends with decreased mortality for both the UK and EU15+ countries (supplementary fig 1). For men, the age standardised death rates for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases decreased from 347 to 101 per 100 000 people in the UK, compared with a decrease from 253 to 83 in the EU15+ countries. For women, the age standardised death rate for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases decreased from 204 to 60 in the UK, compared with a decrease from 155 to 53 in the EU15+ countries. For renal diseases, there were consistent decreasing trends over the observation period in the UK and EU15+ countries (supplementary fig 2). For men, the age standardised death rate decreased from 6.7 to 2.3 in the UK, compared with the decrease from 8.1 to 5.5 in the EU15+ countries. For women, the age standardised death rate decreased from 4.6 to 1.8 in the UK, compared with the decrease from 5.5 to 4.2 in the EU15+ countries.

Discussion

Principal findings

In this observational analysis of national mortality statistics, we found greater mortality from respiratory disease in the UK than in the EU15+ countries over the period from 1985 to 2015. The overall trend of respiratory disease mortality in the UK and EU15+ countries is continuing to decrease, but there remains a persistent difference between the UK and other EU15+ countries. The difference in mortality between the UK and other similar countries does not exist for other chronic medical conditions such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, or death from renal disease. Respiratory disease mortality differences are present across subcategories of respiratory related causes of death, except for cancer related deaths. The UK is an outlier for mortality secondary to obstructive, interstitial, and infectious respiratory disease.

Comparison with other studies

The primary aim of our investigation was to compare mortality from respiratory disease in the UK with the EU15+ countries over the period 1985 to 2015. Our hypothesis was based on previous reports which have suggested relatively high mortality in the UK with respect to specific respiratory disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lower respiratory tract infections. Overall, the trend in respiratory disease mortality is decreasing in both the UK and EU15+ countries at nearly equal rates. Our findings accord with previous reports which found that age specific all cause mortality has decreased in the UK compared with similar countries between 1990 and 2010, but only for men older than 55.3 Previously, it has been postulated that these discrepancies were due, in part, to the legacy of high tobacco use in the UK compared with other countries.12 13 However, this trend has been on the decrease in the 1970s and, despite improvements in reducing tobacco consumption in the UK, we found comparatively high mortality rates persist even in 2015. Pollution could be another factor contributing to the higher respiratory disease mortality. The 2017 WHO World Health Statistics reported 25.7 deaths per 100 000 in the UK attributable to household and ambient air pollution, which is greater than most of the comparator countries used in this investigation (with the exception of Austria, 34.2 per 100 000; Belgium, 30.2 per 100 000; Germany, 32.5 per 100 000; Greece, 45.1 per 100 000; and Italy, 35.2 per 100 000).14 These risk factors are particularly noticeable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A previous Global Burden of Disease study reported that smoking and ambient particulate matter could explain 73.3% of disability adjusted life years owing to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.15

Our analysis does not provide information beyond identification of national differences and the trends observed over this period. Therefore, any discussion of underlying causation remains speculative. However, it should be considered whether a proportion of the observed differences can be regarded as amenable mortality. Amenable mortality has been defined as conditions leading to death or disability which would not occur in the presence of timely and effective medical care.16 It has also been argued that amenable mortality provides a more useful indicator of the success of a healthcare system.17 All respiratory diseases are included within previously reported descriptions of amenable mortality, which could have implications for the UK as an outlier with respect to mortality from these conditions.18

There is a disjunction in the trend for UK respiratory mortality in the early 1990s, with an increase in mortality that contrasts with the near linear trend over the same period in the EU15+ countries. This disjunction is likely to be secondary to coding changes as opposed to a true increase in respiratory mortality. Two relevant changes occurred in the UK at this time. Firstly, the UK changed its coding practices to align with international standards on determining the underlying cause of death (specifically use of “Rule 3”).19 Secondly, the UK adopted automated computerised coding of underlying cause of death in an attempt increase consistency and international comparability.20

For individual causes of death, the trend for lung cancer mortality in men is decreasing both in the UK and in EU15+ countries over the past decade and the trend in women is either neutral or increasing over time. There was no appreciable difference between the UK and EU15+ countries for lung cancer in men and, for women, slightly higher lung cancer mortality in the UK than in EU15+ countries. Lung cancer consistently ranks among the most lethal of cancers and accounted for upwards of 695 000 deaths in men and 681 000 deaths in women, worldwide in 2008.21 Many factors are associated with the development of lung cancer and, globally, lung cancer mortality has fallen substantially, attributed largely to earlier diagnosis and smoking cessation as well as reductions in environmental carcinogens (eg, asbestos).22 The current data suggest that the UK has made substantial improvements in overall lung cancer mortality rates and has kept pace with the remainder of EU15+ countries.

We observed sex specific differences in mortality between the UK and EU15+ countries for obstructive respiratory diseases. Whereas mortality trends for men in the UK are similar to EU15+ countries, women in UK had significantly greater mortality than EU15+ countries with respect to obstructive respiratory diseases. Using similar methods, López-Campos analysed trends in mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using data from the statistical office of the EU (Eurostat).23 These investigators found that, overall, rates of death from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease across the EU were falling, with greater decreases in men than in women over the observation period, and an overall narrowing of the mortality gap between the sexes. Furthermore, these investigators compared mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease between EU member states (by using standardised rate ratios of individual countries) and the entire EU. Mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was noted to be consistently greater in Ireland, Hungary, and Belgium for men, and in the UK and the Netherlands for women. In a subsequent study, López-Campos and colleagues used a prospective audit to show noticeable variability across 13 European countries in resources available for healthcare provision for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.24 Ebmeier and colleagues showed that in individuals aged 5 to 34, global asthma mortality rates have decreased since 1993 to reach a plateau in 2006; they did not find that the UK was an outlier for mortality in this population.25

Mortality from infectious respiratory diseases has decreased over the period from 2001 to 2015 in both the UK and EU15+ countries for both men and women. These findings indicate a higher burden of mortality from infectious causes of death in the UK than in EU15+ countries, regardless of sex. This difference is supported by the 2016 Global Burden of Disease report, which showed higher mortality from respiratory tract infection in the UK than in similar countries (62 deaths per 100 000 in the UK v 38 per 100 000 in both France and Germany).26 In addition, the magnitude of the difference between the UK and EU15+ countries appears to be greater in women, but the exact mechanisms as to why women in the UK would have worse outcomes from infectious respiratory diseases than in men is unclear. One potential explanation includes convergence in the rates of smoking between men and women during the observation period.27

Interstitial respiratory diseases showed noticeable differences between the UK and EU15+ countries and between sexes. We have previously reported on trends relating to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis across EU member states and showed overall increasing trends in most countries.28 While the increasing mortality may be related to its increased incidence in an ageing population, it is also possible that improved diagnostic capabilities are leading to greater case identification.

Strengths and limitations

Our results build on previous work from the Global Burden of Disease and other epidemiological studies.3 15 26 The strengths of our investigation include the use of annual mortality data collected from national surveillance statistics for which the WHO routinely validate to ensure reliability. These data have made it possible to assess the population level trends over an extended observation period to minimise the limitation of making comparisons between countries on the basis of cross sectional data from one year. To further elucidate potential mechanisms driving the differences observed in the current investigation, future work should characterise trends at subnational levels and also make a comparative analysis of health systems with low mortality rates in order to determine how these characteristics differ from those health systems with higher mortality rates from respiratory diseases. Such an analysis could examine the differences in economic factors (eg, gross domestic product and health and social care expenditure), health coverage and health service provision (eg, access to primary and specialist care), and differences in health behaviours (eg, diet, obesity, smoking). These research priorities—in particular health behaviours and adherence—are in agreement with the areas of interest highlighted by patients with chronic lung diseases (box 1).

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the results of our study. Firstly, we made comparisons between the UK and EU15+ countries based on previous studies which have reported a higher burden of disability and mortality in the UK than in these similar economies. However, other important differences between the UK and these countries in terms of population, demographics, and other features may contribute to these different overall health outcomes. Secondly, we did not attempt to assess morbidity or disability associated with respiratory disease and, with the current dataset, we were unable to assess prevalence of respiratory disease in respective countries. Thirdly, there are major gaps in the coverage of death registration and persisting questions regarding the quality of death registration data. For example, although certification of lung cancer has relatively high (>95%) confirmation rate using a tissue diagnosis, other conditions such as pneumonia can have discrepancies between certification and true cause of death.29 30 31 WHO consistently monitors data entry to ensure completeness of data as well as quality of cause-of-death assignment.32 Further, as with any observational study, the possibility remains that substantial confounding exists as there are multiple health, economic, and social determinants that could contribute to health outcomes.

Conclusions

Although the overall mortality from respiratory disease has decreased over the period from 1985 to 2015 in the UK and EU15+ countries, there is a persistent mortality gap between the UK and EU15+ countries. Additional investigations are required to characterise differences in economic, healthcare system, and health behaviour across these countries for patients with respiratory diseases.

What is already known on this topic

Mortality from respiratory disease can be reduced through effective healthcare interventions

National mortality statistics are used to benchmark health system performance and identify countries with high mortality

According to reports including the Global Burden of Disease, the UK has higher mortality from respiratory diseases than other countries with similar health system performance

What this study adds

From 1985 to 2015, mortality from respiratory disease overall was decreasing in the UK and in countries with similar health system performance

Mortality from obstructive, infectious, and interstitial respiratory diseases was higher in the UK than in similar countries

Acknowledgments

We thank Courtney Coleman, from the European Lung Foundation, who helped to identify patients to involve in this work; and the following patients for providing their reflections on our findings: Matt Cullen (Ireland), Dominique Hamerlijnck (Netherlands), Nicola Pilkington (UK), Annette Posthumus (Netherlands), Toni Simpson (UK), and Alan Timothy (UK).

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary materials: Supplementary table 1 and figures 1 and 2

Contributors: JDS and DCM contributed equally to this work. JDS, DCM, and KFC were responsible for the study design, data analysis, and interpretation. JDS, DCM, and JS were responsible for the first draft of the manuscript. JS, MM, and KFC were responsible for the critical review of the manuscript. GDC was responsible for the patient involvement aspects of this work. All authors had full access to the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JDS is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The authors declare no sources of funding for this study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. FC is a senior investigator of the National Institute for Health Research UK.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, et al. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1151-210. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chung F, Barnes N, Allen M, et al. Assessing the burden of respiratory disease in the UK. Respir Med 2002;96:963-75. 10.1053/rmed.2002.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray CJL, Richards MA, Newton JN, et al. UK health performance: findings of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;381:997-1020. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hutchinson JP, McKeever TM, Fogarty AW, Navaratnam V, Hubbard RB. Increasing global mortality from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the twenty-first century. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:1176-85. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-145OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nolte E, McKee M. Measuring the health of nations: analysis of mortality amenable to health care. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:326 10.1136/jech.2003.011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hartley A, Marshall DC, Salciccioli JD, Sikkel MB, Maruthappu M, Shalhoub J. Trends in Mortality From Ischemic Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease in Europe: 1980 to 2009. Circulation 2016;133:1916-26. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marshall DC, Webb TE, Hall RA, Salciccioli JD, Ali R, Maruthappu M. Trends in UK regional cancer mortality 1991-2007. Br J Cancer 2016;114:340-7. 10.1038/bjc.2015.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Viner RM, Hargreaves DS, Coffey C, Patton GC, Wolfe I. Deaths in young people aged 0-24 years in the UK compared with the EU15+ countries, 1970-2008: analysis of the WHO Mortality Database. Lancet 2014;384:880-92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Mortality Database. http://apps.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality/causeofdeath_query/.

- 10.Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf

- 11. Cole TJ. Sympercents: symmetric percentage differences on the 100 log(e) scale simplify the presentation of log transformed data. Stat Med 2000;19:3109-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ 2000;321:323-9. 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davy M. Time and generational trends in smoking among men and women in Great Britain, 1972-2004/05. Health Stat Q 2006;32:35-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2017: Monitoring Health for The SDGs. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255336/9789241565486-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- 15. GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:691-706. 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nolte E, McKee M. Does health care save lives? Avoidable mortality revisited. The Nuffield Trust, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nolte E, McKee CM. In amenable mortality--deaths avoidable through health care--progress in the US lags that of three European countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2114-22. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nolte E, McKee M. Measuring the health of nations: analysis of mortality amenable to health care. BMJ 2003;327:1129. 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation. Rules and guidelines for mortality and morbidity coding. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICD-10_2nd_ed_volume2.pdf.

- 20.Office for National Statistics. Mortality statistics Metadata. https://www.ons.gov.uk/file?uri=/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/howyouobtaindetailsofthenumberofpoliceofficersuicides/mortalitymetadata2014_tcm77-241077.pdf

- 21. Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008-2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:790-801. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cogliano VJ, Baan R, Straif K, et al. Preventable exposures associated with human cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1827-39. 10.1093/jnci/djr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. López-Campos JL, Ruiz-Ramos M, Soriano JB. Mortality trends in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Europe, 1994-2010: a joinpoint regression analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:54-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López-Campos JL, Hartl S, Pozo-Rodriguez F, Roberts CM, European COPD Audit team Variability of hospital resources for acute care of COPD patients: the European COPD Audit. Eur Respir J 2014;43:754-62. 10.1183/09031936.00074413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ebmeier S, Thayabaran D, Braithwaite I, Bénamara C, Weatherall M, Beasley R. Trends in international asthma mortality: analysis of data from the WHO Mortality Database from 46 countries (1993-2012). Lancet 2017;390:935-45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. GBD 2015 LRI Collaborators Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory tract infections in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:1133-61. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30396-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lortet-Tieulent J, Renteria E, Sharp L, et al. Convergence of decreasing male and increasing female incidence rates in major tobacco-related cancers in Europe in 1988-2010. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1144-63. 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marshall DC, Salciccioli JD, Shea BS, Akuthota P. Trends in mortality from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the European Union: an observational study of the WHO mortality database from 2001-2013. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1701603. 10.1183/13993003.01603-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Percy C, Muir C. The international comparability of cancer mortality data. Results of an international death certificate study. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:934-46. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Percy CL, Miller BA, Gloeckler Ries LA. Effect of changes in cancer classification and the accuracy of cancer death certificates on trends in cancer mortality. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1990;609:87-97, discussion 97-9. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb32059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mieno MN, Tanaka N, Arai T, et al. Accuracy of death certificates and assessment of factors for misclassification of underlying cause of death. J Epidemiol 2016;26:191-8. 10.2188/jea.JE20150010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO methods and data sources for country‐level causes of death 2000‐2015. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalCOD_method_2000_2015.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials: Supplementary table 1 and figures 1 and 2