Abstract

The Indian medical education system has been able to pull through a major turnaround and has been successfully able to double the numbers of MBBS graduate (modern medicine training) positions during recent decades. With more than 479 medical schools, India has reached the capacity of an annual intake of 67,218 MBBS students at medical colleges regulated by the Medical Council of India. Additionally, India produces medical graduates in the “traditional Indian system of medicine,” regulated through Central Council for Indian Medicine. Considering the number of registered medical practitioners of both modern medicine (MBBS) and traditional medicine (AYUSH), India has already achieved the World Health Organization recommended doctor to population ratio of 1:1,000 the “Golden Finishing Line” in the year 2018 by most conservative estimates. It is indeed a matter of jubilation and celebration! Now, the time has come to critically analyze the whole premise of doctor–population ratio and its value. Public health experts and policy makers now need to move forward from the fixation and excuse of scarcity of doctors. There is an urgent need to focus on augmenting the fiscal capacity as well as development of infrastructure both in public and private health sectors toward addressing pressing healthcare needs of the growing population. It is also an opportunity to call for change in the public health discourse in India in the background of aspirations of attaining sustainable development goals by 2030.

Keywords: Doctor population ratio, medical council of India, medical education, public health policy, universal health coverage

Background

India is one of the fastest growing economies in the world and the second most populous country. In spite of rapid development achieved in other fields, the performance when judged on healthcare parameters remains poor. One of the dominant discourses in the public health domain within context of provision of Universal Health Coverage is the shortage of adequate number of qualified medical doctors and other healthcare professionals in India. World Health Organization (WHO) has promulgated desirable doctor–population ratio as 1:1,000. Yet, over 44% of WHO Member States reported less than one physician per 1,000 population.[1] Responding to this challenge, there has been a major thrust on increasing the capacity of graduate training programs (MBBS) at medical institutions across India. India has two systems of qualified, professionally trained, and registered medical doctors. The first one is the system of modern medicine introduced nearly 200 years back during British colonial rule and the other one is a system of traditional Indian system of medicine, previously neglected but now patronized and streamlined by the Government of India. The system of modern medicine is largely regulated by the Medical Council of India (MCI) and governed under Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, whereas traditional medicine – AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy) – is regulated through Central Council for Indian Medicine (CCIM). The traditional Indian system of medicine is governed under an independent ministry of AYUSH of Government of India.[2]

MBBS Doctors: Doctors of Modern Medicine

The Lok Sabha (Parliament) was informed by Minister of State for Health that as per information provided by the MCI, there were a total of 10,22,859 MBBS (Modern Medicine) doctors registered with the MCI or State Medical Councils as on March 31, 2017. After considering attrition, it gives a doctor (modern medicine) and population ratio of 0.77:1,000 as per current population estimate of 1.33 billion. The minister also said that emphasis of the government was to increase the number of doctors in the country to improve the doctor–population ratio. Comparable figures in other countries are as follows: Australia, 3.374:1,000; Brazil, 1.852:1,000; China, 1.49:1,000; France, 3.227:1,000; Germany, 4.125:1,000; Russia, 3.306:1,000; USA, 2.554:1,000; Afghanistan, 0.304:1,000; Bangladesh, 0.389:1,000; and Pakistan, 0.806:1,000. Currently, India hosts a total of 479 medical colleges with an annual intake of 67,218 MBBS students. About 12,870 MBBS student positions have been added only in the last 3 years.[3]

AYUSH: Doctors of Traditional Indian System of Medicine

Apart from MBBS doctors, that is, graduates from the medical colleges teaching modern medicine, there is a spectrum of graduate healthcare providers trained in the traditional Indian systems of medicine. The government has recognized those trained in the traditional system with equivalent status in public funded healthcare delivery system; these graduates are also routinely employed by private sector. Department of AYUSH is a governmental body in India entrusted with education and research in Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Homoeopathy, Sowa-rigpa, and other Indigenous Medicine systems. The department was created in March 1995 as the Department of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homoeopathy (ISM & H). AYUSH received its current name in March 2003. That time it was operated under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. An independent Ministry of AYUSH was formed on November 9, 2014 by elevation of the Department of AYUSH. Apart from 297 existing Ayurveda-Siddha-Unani Colleges, under CCIM Act, 1970, there is ambitious plan to establish 47 new colleges proposed Ayurveda (42, 3,200 seats) in undergraduate (BAMS) courses, Unani (4, 260 seats) in undergraduate (BUMS) course, and Siddha (1, 100 seats) in undergraduate (BSMS) course. Also, there are plans to increase undergraduate admission capacity by 800 BAMS seats in the existing 32 Ayurveda colleges and 94 BUMS seats in existing 4 Unani Colleges. These training programs are contributing to the accumulating pool of traditional medical doctors by approximately 10,000/year. In total, there were 7,44,563 AYUSH registered graduates as of January 1, 2015, which by 2017 expected to be 7.6 lac approximately.[4,5]

WHO Recommended Standard Already Achieved (2018)

With minimum age for entry at 17 years and course duration of 5.6 years, Indian medical graduates are licensed to practice medicine by the age of 25 years. Recently, the central and a number of state governments have increased the retirement age of doctors from 60 to 65 years. MCI had officially notified in 2010, 70 years as retirement age for medical teachers. Indian medical graduates serve Indian population for 50 long years as “healers,” “teachers,” and “preachers” by enjoying good health as compared with general population.[6,7,8]

In the hard count now during 2017, 1.33 billion of Indian population is being served by 1.8 million registered medical graduates. So, the ratio is 1.34 doctor for 1,000 Indian citizens as of 2017. This means that India has already reached WHO norm of 1:1,000 doctor population ratio even considering the most conservative estimates including stringent attrition criteria.

India to Achieve Adequate Numbers of MBBS by 2024

The Indian medical education system has been able to pull through a major turnaround and successfully able to double the numbers of MBBS (modern medicine) positions during recent decades.

Further, with an annual intake of 67,218 MBBS students within next 5 years, the system will add 4,70,526 MBBS doctors (from 2017) to a total of 14,93,385 by 2024 even if no new college campuses are setup with more MBBS admissions. On the other hand, India's population has been projected as 1,447,560,463 by 2024. So, by 2024, the doctor–population ratio is expected to be around 1.03 per 1000 population. It is clear that India will reach WHO standard of 1:1,000 doctor (only modern medicine)–population ratio within next 7 years by the current demographic trend, a year before India's 75th independence anniversary.[9]

How Many Doctors do India Needs Actually?

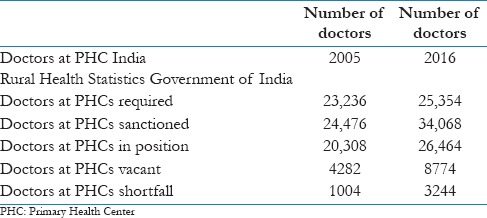

According the Rural Health Statistics released by government of India [Table 1], by 2016, there was a minor shortfall of 3244 of doctors at Primary Health Centers (PHCs), if matched against sanctioned posts; where India has currently capacity of producing 67,000 MBBS doctors per year.[10] The total number of posts sanctioned at PHC in India only 34,068 about half of the current number of MBBS doctors produced annually. The shortfall is miniscule as compared with the capacity. As a matter of fact, there are very few sanctioned positions of doctors employed in public healthcare delivery system, given the Indian population and high morbidity levels. Apparently, there is over supply of MBBS doctors for whom there is no jobs in public sector. The private healthcare industry is largely urban based, hospital centric, and specialty driven and therefore does not have capacity or need to employ basic MBBS doctors. As it becomes clear now, there has been a continued apathy toward employing medical practitioners in the public healthcare delivery system, more specifically in the primary care and community-based domain. Could this be inadvertent? This appears to be a system design where by population has to travel long distances to urban cities in order to even avail basic medical facilities.

Table 1.

Rural health data: Number of doctors in public health system

Current Public Health Interventions and Debates Based on the Premise of Low Doctor–Population Ratio – A Critical Review

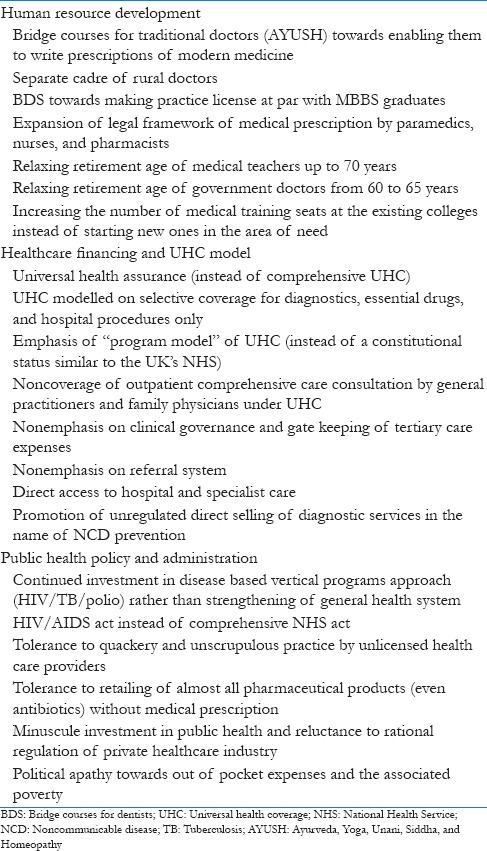

Arguments based on the premise of low doctor–population ratio have been used for launching several public health interventions, more specifically in the areas of human resource development. As per the facts presented in this paper, India has already reached WHO norm of 1:1000 doctor–population ratio. The health system has moved from “not available” to “available but not engaged” status or “available but maldistributed and inefficient.” Few of the prominent interventions and current debates within the domain of public health are enlisted in Table 2. Many of these interventions are not evidence based and appear to be implemented with haste. Few proposed solutions have direct implications on the legal framework of pharmaceutical retail regulation and contribute to emerging global issues such as antibiotics resistance. Health care is heavily politicized from global to local levels. With huge financial resources at stake, it is indeed time to critically review the existing public health debates and interventions. As of now and for the future, public health interventions based on the erroneous assumption of scarcity of qualified doctors are likely to address misplaced priorities.

Table 2.

Current public health interventions and debates based on premise of low doctor-population ratio

Call for Paradigm Shift in Public Health Discourse in India

It is not clear who floated this idea of WHO standard of doctor-population ratio and how it impacts the population-based healthcare intervention outcomes. But, it is popularly quoted by public health experts and appears more frequently in mainstream media.

A country credited with successful Mars Mission definitely has resources and technical capacity to transform age-old crumbling health care delivery system. However, there is a tremendous tension within healthcare policy initiatives. Public health policy should serve public interest or promote trillion dollar healthcare/pharmaceutical industry? Public health policy should address local national health priorities and should align to achieve global goals or serve a select few stakeholders and consumers? Public health policy should address the long-term strategy toward addressing pressing population needs by strengthening the general health system or should meet the priorities set by international donors? Public health policy should address health care as a social and human right issue or it should facilitate achievement of priorities determined by market forces?

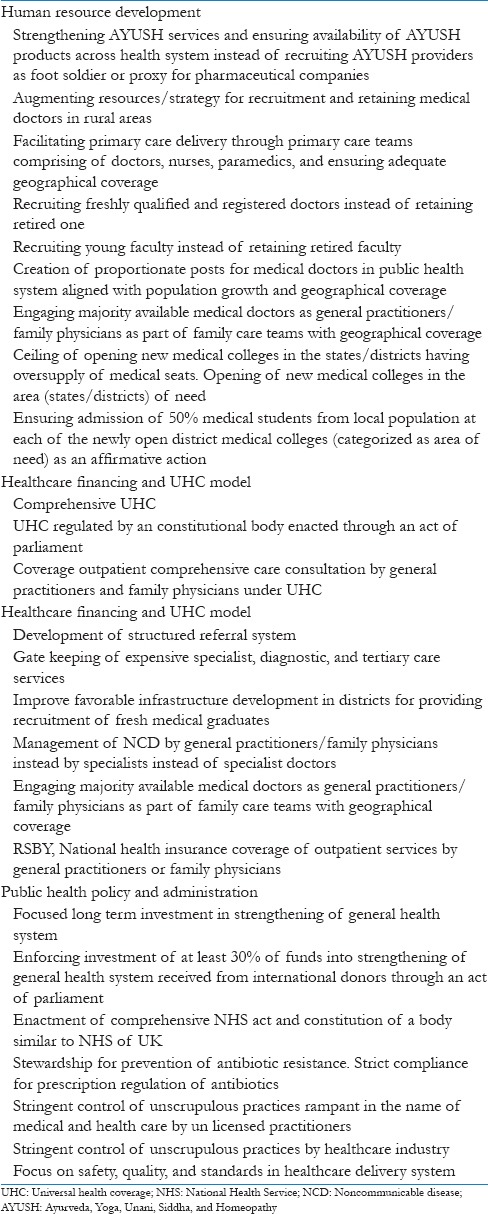

Ultimately, the mainstream politics of the day would define the future direction of public health initiatives in India. However, we call for a paradigm shift in the public health discourse in India and propose a new priority setting listed in Table 3. Low doctor–population ratio is no longer a valid argument for maintaining status quo.

Table 3.

Call for change in public health discourse in India

References

- 1.Density of Physicians (Total Number per 1000 Population, Latest Available Year), Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. Situation and Trends. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/health_workforce/physicians_density/en/

- 2.Ministry of AYUSH. Government of India. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.ayush.gov.in/about-the-systems/sowa-rigpa/introduction-sowa-rigpa .

- 3.Less than one Doctor for 1,000 Population in India: Govt. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/less-than-one-doctor-for-1-000-population-in-india-govt-to-ls/story-olGNMk fVFFWSfZ0I23YOdM.html .

- 4.Summary of AYUSH Registered Practitioners (Doctors) and Population Served as on 1 January. 2015. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.ayush.gov.in/sites/default/files/Medical%20Manpower%20Table%202015.pdf .

- 5.Summary of all India AYUSH Infrastructure Facilities. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 15]. Available from: http://www.ayush.gov.in/sites/default/files/Summary.pdf .

- 6.Advertisement for Filling up the Posts of Faculty and Doctors. Kalpana Chawla under Govt of Haryana. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.kcgmckarnal.org/advertisement.php .

- 7.Advertisement for filling up the Post of Director each in AIIMS at Mangalagiri near Guntur in Andhra Pradesh, AIIMS, Kalyani in West Bengal and AIIMS, Nagpur in Maharashtra. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 09]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/vacancy .

- 8.Medical Council of India Notifications no. No. MCI-34 (41}/2010-Med./29127. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.mciindia.org/documents/e_Gazette_Amendments/MSR_50_100_150_200_250_17.09.2010.pdf .

- 9.Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.populationpyramid.net/india/2024/

- 10.Rural Health Statistics 2016-17: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Available from: https://www.nrhm-mis.nic.in/Pages/RHS2017.aspx?RootFol der=%2FRURAL%20HEALTH%20STATISTICS%2F%28A%29RHS%20-%202017&FolderCTID=0x01200057278FD1EC909F429B03E86C7A7C3F31&View=%7B9029EB52-8EA2-4991-9611-FDF53C824827%7D .