Abstract

Many people in India, especially the poor, face the hurdle of seeking effective health care at an affordable cost, at a distance they can travel, and with the dignity they deserve. According to reports from across the world, it is evident that countries having a strong primary health care system, have better health outcomes, lower inequalities, and lower costs of care. Primary care requires a team of health professionals, workers, and volunteers having a judicious skill mix. Some initiatives have been taken by the government in states like Kerala, Assam, Chhattisgarh, etc., to strengthen the primary health care infrastructure and provide primary care as close to their homes as possible. Staff deficiencies were addressed and training was also provided to the untrained staff. The current review focuses on several other primary care organizations that are working in different parts of the country (rural and urban), for e.g. Healthspring, MeraDoctor, Swasth India, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY) Outpatient Pilot Program, etc. The current review also throws spot light on the type of primary health care system existing in countries like China, South Africa and Brazil. Some lacunae in service delivery are also identified and addressed so that changes can be incorporated at the policy and program level.

Keywords: Family, organizations, primary health care, population, therapeutics

Introduction

Primary care at its most root definition is medical care delivered with the patient and the community in mind. Traditionally, it refers to the point of first contact between a person and the health system; the point where individuals receive care for most of their routine health needs.[1] Family physicians (FPs) play a significant role in the central health system and need to be equipped with a broad range of clinical skills in order to meet the needs and expectations of the communities they serve. However, central to the concept of primary care is the patient.[2] Primary care includes health promotion, disease prevention, health maintenance, counselling, education of patient, diagnosis and treatment of both acute and chronic illnesses in a range of health care settings (e.g., office, inpatient, critical care, long-term care, home care, day care, etc.).[3] It provides patient advocacy in the health care system to accomplish cost-effective care by coordinating different health care services.

A primary care team (PCT) is a multidisciplinary group of health and social care professionals who work together to deliver local accessible health and social services to a defined population of between 7,000 and 10,000 people at “primary” or first point of contact with the health service [Figure 1]. The population to be served by a team will be determined by geographical boundaries and/or the practice population of participating general practitioners (GPs).[4] Family physicians, nurses, dieticians, mental health professionals, pharmacists, therapists comprise an essential component of primary care team. These teams provide a “one stop approach” and can meet or arrange the vast majority of the health care needs of the public.

Figure 1.

Primary care team members catering to various health issues of the population

Because of weak primary care system and absence of referral system in India, tertiary care public health facilities are often overburdened and short of resources. Moreover, assault on physicians due to dissatisfaction is also a common occurrence in India.[5] There is a scarcity of doctors employed in the public health system who can be incorporated into the primary care teams. Over half of the community health centers (CHC) lack specialist doctors. Majority of the newly-qualified doctors prefer to work in hospital-based specialties instead of primary health centers (PHC).[6] This has resulted in non-physician clinicians (NPC) serving at PHCs. There is a growing recognition of the fact that Indian public health strategy should be given highest priority to maximize health benefits with access and affordability.[7]

Current scenario on quality of primary care and need for primary care teams

There is a considerable shortfall of PHCs, CHCs, and district hospitals even though the Government of India has expanded its health infrastructure in the last decade. These gaps are particularly present in states like Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh.[8] Results of a study conducted on the quality of primary care in public and private clinics using standardized patients in rural Madhya Pradesh and urban Delhi are instructive.[9] The design of the study can be used for comparison in rural/urban areas and public/private clinics. Approximately 70% of the rural practitioners had no medical training and more than 20% were trained in AYUSH. Untrained staff (no medical training) used to attend most of the public clinics (63%). The quality of care provided was poor, in addition to brief consultation times and very limited use of correct protocols. Only 41% of the treatments provided were medically appropriate. Harmful or unnecessary medications were also prescribed by practitioners in majority of the cases. However, it was finally analyzed that provider effort rather than medical training, may be a stronger determinant of quality care. Recent evaluations indicate that care uptake for chronic illnesses in the public sector remains very low in Uttar Pradesh (45%), Madhya Pradesh (63%), Jharkhand (70%) but high in Tamil Nadu (94%).

Public health training in India is also “doctor centric.” There is little of no growth of nursing and allied health professions in the country.[7] Majority of the training courses for nurses provided by some private institutes are of poor quality and lack capacity building. These type of cadres also have a very minor role to play in family practices. This lack of representation signals a need to invest in their public health and management skills.

Initiatives in some states including Kerala

The Universal Health Coverage Primary Health Care Project was started in December 2012 in Kerala with an aim to ensure the availability of quality treatment and preventive services at the public primary care institutions closet to the community.[10] Kerala has achieved substantial population coverage in terms of its primary healthcare infrastructure. Several changes were introduced including new infrastructure to make environment patient friendly, to redesign patient flow, and to reduce waiting time. Some other changes included electronic registration of patients for ease of data entry and to track patient record, establishment of laboratory and diagnostic services, procurement of drugs, equipment, and other supplies. These improvements led to a considerable increase in the level of commitment, team spirit, and involvement of medical staff with the local self-government representatives. There was a vast improvement in the health seeking behavior of the patients. Patients started visiting local primary care centers instead of going to city for treatment. Active engagement of the facility staff in the health education camps led to the increase in health awareness within the community.[10]

The Kadakampally primary health center in Kerala was upgraded to a Family Health Centre (FHC) in August 2017 under the “AARDRAM” program of the government. The services of four doctors and three nurses are available daily for 9 hours. A Lab technician is also posted there. The doctor at the Family Health Centre is reasonably skilled to manage health problems which can be managed there. The e-health scheme of the family health center was also inaugurated. The family health centers, set up by renovating primary health centers and overcoming their limitations, aim at catering to primary health care requirements of a family.[11]

According to a recent health policy discourse in Kerala, all private health care facilities will be regulated by ensuring that they are all registered. Moreover, in order to strengthen public health care, the government plans to increase state government expenditure on healthcare from the current 0.6% of the Gross State Domestic Product to at least 5%, by increasing it by 1% every year. The panel has suggested classifying public health facilities into three categories—primary health centers, community health centers and family health centers as tier one hospitals, taluk, and district hospitals into tier two and selected district hospitals and medical college hospitals into tier three category.[12]

A new cadre of health care workers known as “rural medical practitioners” were trained to address primary health care needs of the people in some states like Chhattisgarh, Assam and West Bengal.[13] These practitioners are placed in rural settings having staffing deficiencies. Since 2010, these informal practitioners provided consultation to 1.9 million outpatient cases and conducted twelve thousand deliveries, with the assistance of auxiliary nurse midwife in Assam equipped with necessary skills and supplies. The high-level training of these practitioners is conducted at a dedicated institution that is linked to the state medical college. While the Chhattisgarh program is currently discontinued because of some problems with the central government, the effort proved to be successful in solving the staffing problems at primary health centers.

An outpatient health care program was piloted by Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY) in Puri, Orissa, and Mehsana, Gujarat.[14] This program provides primary care consultations and drugs to eligible patients by the primary care teams. Till Feb 2013, nearly 7 lakh people had enrolled under this program in both the districts. Approximately 60% of the people used the services and nearly 50% of used them repeatedly. Directed education campaigns were also organized for beneficiaries, providers, and local panchayat officials. This particular program also led to a reduction in inpatient claims costs of around 15% in both the districts.

Three health systems projects have been started by the World Bank in states of Rajasthan, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu to bring an improvement in the health of tribal communities in partnership with local non-government organizations.[15] In Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, tribal auxiliary nurse midwives, and counsellors are being recruited into the primary care team and trained to provide outreach consultation and treatment for communities and to guide patients during their visits to public health facilities. A 24-hour help desk has also been introduced in the state of Karnataka to address complaints and to mediate between patients and service providers. A sizeable population (6–7 Lacs) availed benefits from the services provided by the projects.

Primary care teams and organizations

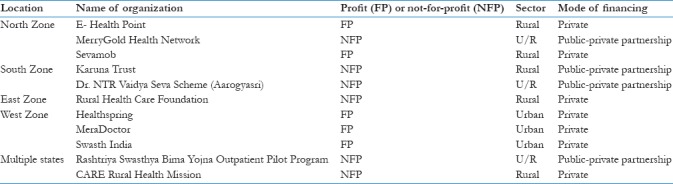

There are several organizations which are working in some states providing primary health care to the people in different ways [Table 1]. They have their own primary care teams which cater to the primary health care needs of the people in both urban and the rural areas. Consultation and treatment is provided to the people regarding their problems at an affordable cost. Some of the important ones are discussed below.

Table 1.

Classification of primary care teams and organizations

Healthspring

Healthspring is a Mumbai-based organization having a network of seven primary health care centers and over 50 emergency care providers.[16] It was launched in 2010 to provide quality primary care to middle and upper middle class urban families in order to reduce the need for expensive and complicated tertiary care. Families are provided teleconsultations, clinic visits, referrals to specialist doctors and 24-hour emergency care through this network. Experienced doctors are recruited into the primary care team and are paid good salary. Consumer feedback is an important component of Healthspring. It is reported that they are able to treat up to 90% of patients at the primary care level, avoiding the need for tertiary care for many patients.

MeraDoctor

People are provided with phone-based medical consultation under this innovative platform. A package of four services are provided for families who enroll under MeraDoctor, with a nominal fee of Rs. 3000 per year.[17] The package comprises of unlimited consultation from a doctor over the phone, discounted drugs at empaneled network centers, hospital care and diagnostics, a hospital cash incentive of Rs. 500 per day of hospitalization and accidental coverage. Routine training and strict monitoring are also conducted by the organization. Preferably young doctors are hired into their primary care team who are comfortable using technology. Till date, approximately 35000 people have enrolled with MeraDoctor in states like Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, the National Capital Region, and Mumbai. Majority of the people seeking health care are from middle and upper class. As teleconsultation is a new concept, the organization wants to complement this business model with the primary care network.

Rural health care foundation

It was founded in 2007 with an aim to provide access to primary care for rural population and that too at an affordable cost.[18] This foundation has currently eight centers in West Bengal and is planning to expand the network in other states. Till date, around 800,000 patients have availed primary care services under this scheme. Patients avail outpatient care in departments of general medicine, ophthalmology, dental, and AYUSH. By paying just Rs. 50, patients can avail consultation and medicines for a period of seven days. Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) are also engaged with this foundation to provide free cataract and cleft lip and palate surgeries, distribution of wheel chairs and provide eye glasses at subsidized rates. To cover and maintain low cost care, philanthropic funds are raised and pharmaceutical companies are involved by the foundation.

Swasth India

It is network of primary care clinics located in urban slums of Mumbai as people living here have limited access to high quality health care.[19] Eight clinics are operated by this network registering approximately 35000 families under them. These clinics offer primary care services, dispense drugs, conduct diagnostic procedures and offer day care. Dental consultation is also provided in some of the clinics. Health promotion and preventive activities are also carried out in the local community and schools. The patients are offered 40% discount by this organization by prescribing generic drugs, not charging referral fee and bypassing intermediaries. Effective use of technology is done to conduct all its operation ranging from referrals to patient records. In order to generate employment for local people, staff is recruited from within the community or surrounding areas.

Sevamob

Founded in 2011, this company is transforming the delivery of primary health care and insurance to low income consumers in developing countries.[20] This company makes use of a Mobile app to provide health care to students in schools and employees working in factories and organizations for a small monthly subscription. Basic primary care, drugs and prescriptions are delivered on-premise by mobile clinics with the help of mobile technology. In cases of advanced care, the teams are supported by back-office specialist doctors, a 24-hour medical call center and network hospitals. The primary care mobile teams consist of dental doctors and sales personnel who carry Android tablets having a mobile software that has the capacity to work without any network in remote rural areas. Basic primary care services are also provided at the door step for subscribers that includes dental check-ups, vision screening, routine blood tests, ECG and diet counselling. Medicine dispensing is also done for nutritional deficiency diseases and common ailments. Back-office MBBS specialists are consulted in case prescription is needed by creating a ticket with picture and description of symptoms. Emergency services are provided by network hospitals having their in-patient health insurance up to Rs 50,000. Sevamob in running successfully in four districts of Uttar Pradesh and has enrolled almost 80,000 subscribers.

Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY) outpatient pilot program

This particular program was launched in Orissa and Gujarat in collaboration with ICICI Foundation in 2011 with no additional cost to the program enrollees.[21] Households were informed that during the year (2011–12), in addition to inpatient healthcare services, the RSBY smart card entitled them to outpatient healthcare services as well. Free consultation and drugs are provided at networked public and private providers under this outpatient program. The program expanded its education and communication channels for targeting communities and health care providers to encourage people to use it. This outpatient pilot program is also linked with other government run health care programs like Janaushudhi. Latest interactive communication techniques are used in remote areas of the country to engage rural population. More providers are now keen to invest in the necessary technology after witnessing high patient volumes. Early analysis of usage patterns indicates that the outpatient benefits have reduced the average size of inpatient claims, an important validation of its need and potential. A total of 131,966 households and 401,048 individuals in Puri and 78,283 households and 275,487 individuals in Mehsana were enrolled. This aggregates to almost 0.7 million people covered under the pilot project.

Primary health care in practice in underserved areas: AMRIT clinics

These clinics were set up in order to provide low cost, high quality primary health care to people living in remote, underserved areas, and vulnerable communities in Udaipur district of Rajasthan.[22] These clinics provide promotive, preventive, and primary curative care to about 2000 families residing in remote and scattered areas of this district. The clinics are managed by primary care staff consisting of three skilled qualified nurses, two trained health workers, and about 10–12 community workers. A weekly visit is also made by a general physician who is also available round the clock for consultation and emergency management. There is also provision of an ambulance and support staff that help linking with other public or private sector health care facilities in the region when required. During one year of its operations of the two clinics, more than 6000 patients have visited the clinics (about half of which were by women), have reached more than 1000 women for antenatal care, and have significantly increased institutional childbirths in their catchment population.

Mohalla clinics

This initiative was launched by the Aam Aadmi Party in New Delhi in 2015 to provide quality primary health care services accessible to the underserved population of Delhi at their door step.[23] These are called as Aam Aadmi Mohalla Clinics (AAMC), which are in the form of a pre-engineered insulated box type structures located at different slum areas in Delhi. The following services are provided by these clinics:

Basic medical care based on standard treatment protocols which include curative care for common illnesses like fever, diarrhea, skin problems, respiratory problems, etc.

Empaneled laboratories carry out all the lab investigations

All drugs are provided free of cost to the patients as per the essential drug list

Preventive services such as ante natal and post-natal care of women, nutritional status and diet counselling are also provided

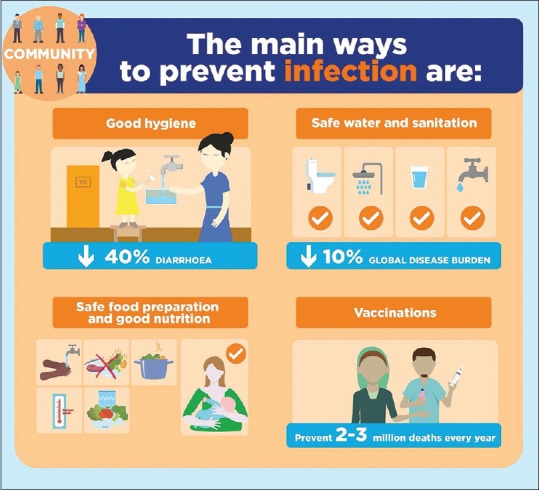

Health education is also provided to the patients to make them more aware regarding different diseases and importance of maintain good hygiene, good nutrition and drinking safe water to prevent infection [Figure 2]. These clinics also counsel patients about the dangers of lifestyle diseases like diabetes and arthritis. The focus is on prevention and not cure.

Figure 2.

Health education regarding different ways to prevent infection

These clinics are opened for at least 4–6 hours every day and serve approximately 10,000–15000 population living with 2–3 km radius of the clinic. It was officially reported that 32 lakh patients have availed healthcare services from 160 such clinics till December 2017. There is widespread acknowledgment that these clinics have improved access to health services by qualified providers, to the poorest of the poor.[23]

Primary care services in China, South Africa, and Brazil

China has made remarkable progress in strengthening its primary health-care system. Nevertheless, the current system faces numerous challenges in structural characteristics, incentives and policies, and quality of care, all of which diminish its preparedness to care for a fifth of the world's population.[24] Primary care is provided by General Practitioners (GPs), which includes nurses as well as traditional Chinese herbalists. Selected primary care service are provided by these people for common ailments, chronic ailments, and preventive care such as vaccinations. Because of shortage of primary care doctors, many senior doctors are working as physicians or specialist converted GPs and are given the task for setting up of CHCs. Primary care has been recently introduced as a new discipline in medical schools in China and consequently there are only few GP departments in medical schools and most of them are managed by public health specialists. Hence, there is very minimal exposure to primary care at the undergraduate level. Post graduate full-time training over 3 years with 2.5 years in hospital rotations and then 6 months in the community has been recently started. On-the-job training is provided for the specialists that have been converted to work as GPs before writing the certification exams. Re-training for GPs to work in rural areas is also provided.[25]

In South Africa, comprehensive primary care services are offered through nurses that are facility-based.[24] Nurses might be supervised by visiting doctors on a weekly or bi weekly basis, and to cater to larger PHCs and CHCs, there would be a team of multi-professionals consisting typically of nurses, doctor(s), pharmacist, allied health professionals. There is now an accredited 4-year post graduate training program to become a Family Physician. This type of training imparts expertise to a GP to work as a competent clinician, provide consultation to the primary care team, support a community-orientated primary care approach and imparting clinical training to medical students, interns, clinical associates, or registrars.[26] Most of the strategies in this country focus on training of both primary care doctors and FPs. A training program was also conducted for primary care providers and clinical nurse practitioners to counsel patients with risky lifestyle behaviors as a part of everyday primary care.[27]

In Brazil, the main concern is largely about community-based primary care with multi-professional family health care teams. The government created the Family Health Strategy (FHS) to help improve access to health services through primary health care teams developing interdisciplinary actions.[28] These teams cater to the primary care needs of a population of around 4000 people in a defined geographic area, and each community health worker is expected to serve approximately 750 people in the community. Comprehensive primary care is also provided by the basic health unit including some oral health care needs. There are only 4000 doctors trained as FPs and hence there is a shortfall of family physicians. The lack of family physicians can be traced primarily to the medical schools where training supports other specialties besides family medicine. There is exposure to primary care and community-based education during the 6-year undergraduate medical course. There is a full time 2-year residency program to be a FP in Brazil. Training takes place in the community, primary care facilities, and referral hospitals. However, it was proposed by family physicians during a recent survey that attainment of clinical communication skills and professionalism competencies should be required for undergraduate students during their course.[29]

Conclusion and Recommendations

Utilization of primary care teams in Universal health coverage is an important and significant step for improving health of the vulnerable populations. However, still there are wide gaps that need to be filled in order to effectively reach every segment of the country's population. Primary health care services in India are located too far from the populations they serve and suffer from inadequate public investments. Moreover, these type of services rely too heavily on the presence of doctors, despite having shortage of doctors throughout the nation. Since many doctors do not often reside in the rural or remote areas, the primary health centers in these areas become dysfunctional. Unlike many Western countries, there is no cadre of primary care providers in our country, where General Physicians and Nurse Clinicians are the certified primary care providers. MBBS doctors are by default the primary care providers in this country with no supplementary training. Nurses are only supposed to assist the doctors. There is an urgent need for strengthening primary health care using new ways to service delivery to ensure that under-privileged families receive affordable and good quality healthcare. Following characteristics can be incorporated into the new model:

Primary health care facilities should be managed by nurse-clinician/physician assistant, providing comprehensive primary care to a catchment population within a maximum of 1-hour travel time

These should be supported and supervised by a primary care physician, with one physician catering to only 4-5 such facilities using a functional transport system and appropriate technology. Physician should be consulted before arriving at a final diagnosis about a rare or specific disease

There should be a proper link with the remaining health ecosystem through an active negotiating system

Work in collaboration with other community-based social services

These should preferably be public funded with possible small contributions by the community

Residency posts in family medicine should be introduced at a larger scale across the country with an emphasis on enhancement of surgical and anesthetic skills. Moreover, A Family Physician Impact Evaluation Tool can be used to measure the impact of family physicians on the state health services according to the expected roles.[30]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Primary care in Alberta. Primary care initiative [monograph on the internet] Edmonton; 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 12]. Available from: http: www.albertapci.ca . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rieselbach RE, Feldstein DA, Lee PT, Nasca TJ, Rockey PH, Steinmann AF, et al. Ambulatory training for primary care general internists: Innovation with the affordable care act in mind. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:395–8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00119.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright B, Nice AJ. Variation in Local Health Department Primary Care Services as a Function of Health Center Availability. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000112. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: A practical guide. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:182–92. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mash R, Almeida M, Wong WC, Kumar R, von Pressentin KB. The roles and training of primary care doctors: China, India, Brazil and South Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:93. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao KD, Sundararaman T, Bhatnagar A, Gupta G, Kokho P, Jain K. Which doctor for primary health care? Quality of care and non-physician clinicians in India. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao M, Mant D. Strengthening primary healthcare in India: White paper on opportunities for partnership. BMJ. 2012;344:e3151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anant P, Bergkvist S, Chaddaani T, Katyal A, Rao R, Reddy S, et al. Landscaping of Primary Healthcare in India. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 07]. Available at: www.accessh.org .

- 9.Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B. In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Affairs. 2013;31:2774–84. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perabathina S, Ellangovan K. Universal Health Coverage in Kerala Through a Primary Care Pilot Project. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 08]. Available from: accessh.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Kerala-PHC-Pilot-Project.pdf .

- 11.Aardram. The mission on Health. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 May 05]. Available from: https://kerala.gov.in/documents/10180 .

- 12.Scroll.in, Public Health. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 May 05]. Available from: scroll.in/pulse/875749/kerala-is-attempting-a-comprehensive-healthcare-upgrade-with-its-ambitious-new-health-policy .

- 13.CIPS. Bridging the Divide. Three Year Medical Rural Practitioner Course in Assam: A Case Study. Hyderabad: Center for Innovations in Public Systems, Administrative Staff College of India; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.ICICI Foundation. Pilot Project Introducing Outpatient Healthcare on the RSBY Card– A Case Study. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 09]. Available from: http://www.icicifoundation.org/media/OP_Report.2013.pdf .

- 15.World Bank. (2011). Improving Health Services for Tribal Populations. New Delhi: World Bank and Ministry of Finance; [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 09]. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INDIAEXTN/Resources/295583-1320059478018/INTribalHealth.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 16.HealthSpring, Family Health Experts [homepage on the internet] 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 13]. Available from: www.healthspring.in .

- 17.MeraDoctor-Free doctor's advice [homepage on the internet] 2015. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 13]. Available from: www.http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/meradoctor .

- 18.Recent and Allied Activities-Rural Health Care Foundation [homepage on the internet] 2012. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 19]. Available from: www.ruralhealthcarefoundation.com .

- 19.Swasth Health Centres (Swasth Foundation) [monograph on the internet] 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 19]. Available from: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/swasth-health-centres-swasth-foundation .

- 20.Sevamob: Transforming primary healthcare [homepage on the internet] 2013. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 19]. Available from: http://iseeindia.com/2013/11/13/sevamob-transforming-primary-healthcare .

- 21.Pilot Project Introducing Outpatient Healthcare on the RSBY Card - A Case Study [homepage on the internet] 2012. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 20]. Available from: http://www.icicifoundation. org/media/publication/OP_Report_Mar13_lowres_final_04.04.2013.pdf .

- 22.Basic Health Care Services- Providing high quality, low cost, primary health care to last mile communities [homepage on the internet] 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 22]. Available from: http://bhs.org.in/why-is-primary-health-care-the-best-approachfor-future-of-health-care-in-india .

- 23.Lahariya C. Mohalla Clinics of Delhi, India: Could these become platform to strengthen primary healthcare? J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6:1–10. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_29_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Lu J, Hu S, Cheng KK, De Maeseneer J, Meng Q, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet. 2017;390:2584–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mash R, Almeida M, Wong WC, Kumar R, von Pressentin KB. The roles and training of primary care doctors: China, India, Brazil and South Africa. Hum Resource Health. 2015;13:93. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mash R, Ogunbanjo G, Naidoo SS, Hellenberg D. The contribution of family physicians to district health services: A national position paper for South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract. 2015;57:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malan Z, Mash B, Everett-Murphy K. Development of a training programme for primary care providers to counsel patients with risky lifestyle behaviours in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2015:7. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v7i1.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blasco PG, Lamus F, Moreto G, Janaudis MA, Levites MR, de Paula PS. Overcoming challenges in primary care in Brazil: Successful experiences in family medicine education. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29:115–9. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2018.1428917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franco CA, Franco RS, Lopes JM, Severo M, Ferreira M. Clinical communication skills and professionalism education are required from the beginning of medical training – A point of view of family physicians. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:43. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1141-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasio KS, Mash R, Naledi T. Development of a family physician impact assessment tool in the district health system of the Western Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:204. doi: 10.1186/s12875-014-0204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]