Abstract

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an autoimmune, potentially life-threatening disease causing blisters and erosions of the skin and mucous membranes associated with intraepithelial acantholysis. The underlying mechanism responsible for causing intraepithelial lesions is the binding of immunoglobulin G autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a transmembrane glycoprotein adhesion molecule present on desmosomes. Histological features comprise intraepithelial cleft and Tzanck cells. Corticosteroids remain the mainstay of the treatment plan. In this article, we have discussed about the diagnosis of three patients suffering from PV, the treatment rendered, and the outcome of the same.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, Nikolsky's sign, Tzanck cells, vesicles

Introduction

The word “Pemphigus,” derived from the Greek word “Pemphix” meaning bubble or blister, was originally used by Wichman in 1791, for describing a chronic blistering disease[1] that corresponds to present-day pemphigus vulgaris (PV). Pemphigus includes a group of autoimmune, intraepithelial disease causing mucocutaneous blisters and erosions, mediated by circulating autoantibodies directed against keratinocyte cell surfaces of intercellular junctions.[2] The two major groups are PV and pemphigus foliaceus. Their difference lies in the level of acantholysis, with the former in the suprabasilar level and the latter in the subcorneal level. The other forms are vegetans, erythematosus, IgA pemphigus, and paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP).[3] Generally, PV affects patients in their fifth and sixth decades of life; shows a strong genetic and environmental association; and is more prevalent in certain ethnic groups, such as Ashkenazi Jews, Japanese, and populations from the Mediterranean ancestry.[4]

Case Presentation

Case 1

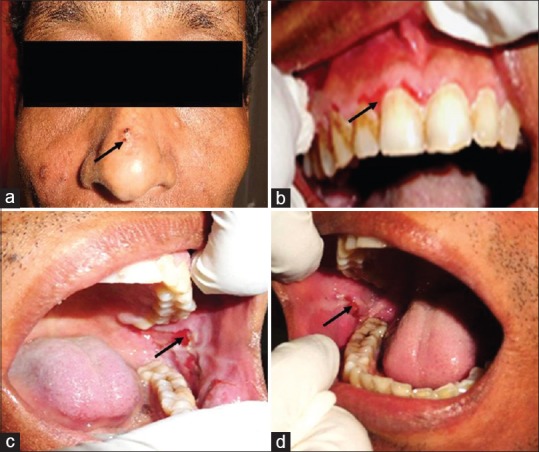

A 45-year-old male patient arrived in the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, with a chief complaint of ulceration in the mouth and body since 2 months, with a history of burning sensation on taking hot and spicy food. Medical history revealed that he was suffering from this problem since 2 years and was on corticosteroids that provided temporary relief. A relapse of short duration and periodic recurrence was associated with discontinuation of medication. On extraoral examination, painful ulcers and blisters were present on the bridge of the nose [Figure 1a], while intraorally, desquamative gingivitis was seen on the marginal gingiva in relation to 11, 12, and ulcerations seen on bilateral posterior buccal mucosa [Figure 1b–d]. Personal and family history was non-contributory. Bilateral submandibular lymph nodes were enlarged, tender, soft mobile, and tender.

Figure 1.

Blisters were present on the bridge of nose (a), while intraorally, desquamative gingivitis was seen on the marginal gingiva in relation to 11,12, and ulcerations seen on bilateral posterior buccal mucosa (b,c and d).

Case 2

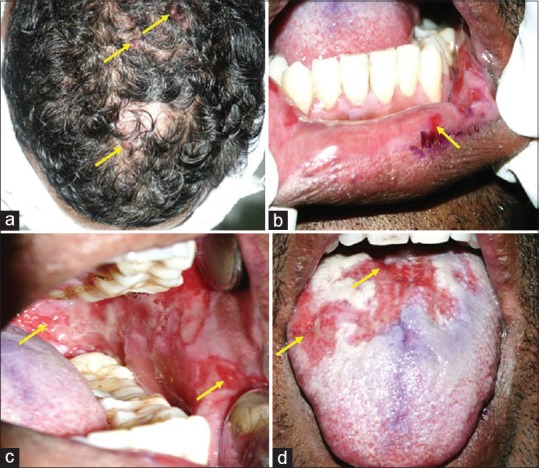

Another 34-year-old male patient presented with a chief complaint of multiple ulcers in the mouth, inability to taste and swallow food and liquid, and hoarseness of voice since 5 weeks. Detailed extraoral examination revealed fresh-ruptured vesicles on the scalp [Figure 2a], while intraorally painful ulcers with irregular, ragged margins were seen on the lower lip and labial mucosa, and bilateral buccal mucosa extending posteriorly up to the retromolar trigone and oropharynx. Lower lip exhibited ruptured blister with erosion, the dorsum of the tongue had a thick, diffuse, white coating, while the buccal mucosae showed erosions with pseudomembrane formation [Figure 2b–d].

Figure 2.

Fresh-ruptured vesicles on the scalp (a) seen, while intraorally, irregular ulcers with ragged margins were present on the labial mucosa (b), bilateral buccal mucosa (c), and dorsum of the tongue (d) - which also exhibited a thick, diffuse, white coating.

Case 3

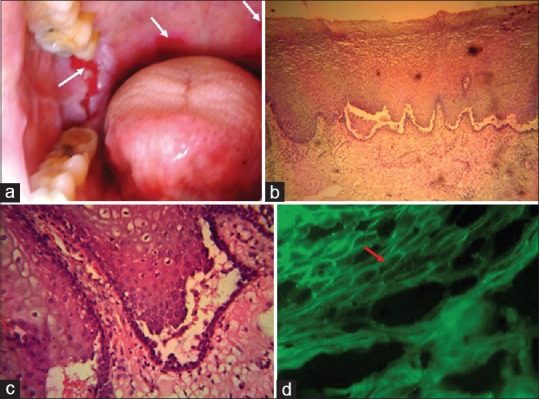

A 28-year-old female patient reported with difficulty in eating and swallowing due to multiple painful ulcers in right buccal mucosa and soft palate [Figure 3a].

Figure 3.

Multiple painful ulcers in right buccal mucosa and soft palate (a). Stained Haematoxylin and Eosin sections [×400] revealed stratified squamous epithelium with intraepithelial blister formation, characteristic suprabasilar cleavage, and presence of acantholytic large, rounded keratinocytes with a hypertrophic nucleus and a perinuclear halo - “Tzanck cells” (c) in the split area. DIF revealed intercellular substance deposition of IgG, : characteristic “fish-net appearance” (d).

In all the cases, based on clinical examination and positive Nikolsky's sign, a provisional diagnosis of PV was put forth with the following differential diagnoses:

Differential diagnosis

Case 1: Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), recurrent herpes simplex (RHS) (immunocompromised cases), bullous lichen planus (BLP)

Case 2: Erythema multiforme (EM), PNP

Case 3: MMP

Investigations

Routine hematological and biochemical investigations performed in both cases were within normal limits. Incisional biopsy was performed in all the cases from perilesional site of buccal mucosa. Stained Haematoxylin and Eosin sections [×400] revealed stratified squamous epithelium with the striking feature of intraepithelial blister formation, characteristic suprabasilar cleavage [Figure 3b], and presence of acantholytic large, rounded keratinocytes with a hypertrophic nucleus and a perinuclear halo - “Tzanck cells” [Figure 3c] in the split area. Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and edema in the sub-epithelial and perivascular region was evident. Direct immunofluorescence assay revealed intercellular substance deposition of immunoglobulin G (IgG), giving rise to the characteristic “fish-net appearance” [Figure 3d]. Based on the above clinical and histopathological findings, a final diagnosis of PV was made.

Treatment

Case 1

The patient who was already on prednisolone since 2 years was treated with deflazacort (6 mg) thrice daily for 10 days with gradual dose tapering. After 6 weeks, skin and oral lesions had regressed slowly. However, the patient developed fresh outbreak of intraoral bullae again after 1 month, following which azathioprine 50 mg was advised twice daily for a month along with deflazacort (6 mg).

Cases 2 and 3

Patients were started on prednisolone (80 mg), multivitamins, and esomeprazole (40 mg). The dose was tapered to 60 mg after 2 weeks on first follow-up. There was marked improvement of the lesions on second follow-up. Both these patients are currently on a diurnal therapy of prednisolone 5 mg, and to date, no other lesions have been reported.

In all the cases, oral prophylaxis was performed, and a topical application of a mixture of two ointments: 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide, with clotrimazole, beclometasone and neomycin was advised along with analgesic benzydamine hydrochloride (0.15%) mouthwash for 7 days.

Discussion

The classic lesion of pemphigus is a thin-walled bulla arising on otherwise normal skin or mucosa, which rapidly breaks and continues to extend peripherally, eventually leaving large denuded areas. This disease also exhibits positive “Nikolsky's sign” – the ability to induce peripheral extension of a blister and/or removal of epidermis as a consequence of applying tangential pressure with a finger or thumb to the affected skin, peri-lesional skin, or normal skin in patients affected or suspected with pemphigus.[5] The pathophysiology of Pemphigus, governed by the mechanism of primary acantholysis, has been explained by the “Desmoglein compensation theory” and “Multiple hits hypothesis” among several other proposed concepts.[6,7,8,9] Acantholysis (Auspitz, 1881) means loss of coherence among epidermal cells due to the breakdown of intercellularties – chiefly made of glycoproteins desmosomes and desmocollins, in conjunction with cytoplasmic plakoglobin and plakophilin. Primary acantholysis refers to the separation of keratinocytes by the severance and disintegration of desmosomes as a result of direct injury to desmosomes or due to the hereditary constitutional defects.[10] IgG autoantibodies, of both G1 and G4 subclasses, bind with (i) desmosomal transmembrane adhesion molecules, namely, desmoglein 1 (expressed in superficial epidermis) and desmoglein 3 (expressed in oral mucous membrane and parabasal epidermis),[6] (ii) desmocollin 3 (expressed in basal, spinous, and lower granular layers),[7] (iii) non-desmosomal proteins such as pemphaxin, alpha 9-acetylcholine receptor and thyroperoxidase,[8] and (iv) mitochondrial proteins.[9] Thus, pemphigus is a complex disease impelled by at least three classes of autoantibodies directed against desmosomal, non-desmosomal, mitochondrial, and other keratinocyte autoantigens. Post intercellular-glycoprotein attachment loss, gaps are created, through which there is fluid influx from the dermis, and cavity formation, leading to intraepidermal clefts, vesicles, and bullae of pemphigus. The now loose clumps of epithelial cells, called the “Tzanck cells,” lying free within the vesicular space, then become rounded up and are characterized by degenerative changes such as nuclear swelling and hyperchromatic staining (in cytological smears).[10]

In 60%–90% cases, the oral lesion is the first sign usually beginning as classic bulla on a non-inflammed base, followed by shallow irregular ulcer as the bulla breaks rapidly. The lesions most commonly start in areas subject to frictional trauma such as the buccal mucosa along the occlusal plane, followed by palate, gingiva, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, conjunctiva along with extensive skin lesions.[11] In all three cases, the noticeable point is that all the patients had visited due to oral lesions, which caused pain, burning sensation, difficulty in consuming food, dysphagia, and hoarseness of voice. Oral blisters have a thin roof, which readily rupture in the face of trauma, leading to multiple chronic painful ulcers, bleeding ulcers, and erosions that heal with difficulty.[12] In addition, the first case manifested desquamative gingivitis which resulted in considerable pain, plaque accumulation, and poor oral hygiene.

Detailed history is essential in distinguishing the lesions of pemphigus from those caused by acute viral infections such as herpes and EM. Because a similar clinical picture is seen in undiagnosed and/or untreated immunocomprised patients, suffering from RHS infections in the form of atypical ulcers may last several weeks or months. Moreover, cytological presence of Tzanck cells may complicate the diagnosis. None of the three cases gave any positive history compromised immunity like acquired immune deficiency syndrome or chemotherapy, organ transplant. Hence, RHS infection and EM could be safely ruled out.

Biopsy for PV is done best on intact vesicles and bulla less than 24 h old, preferably from the advancing edge of the lesion.[12] Supra-basilar acantholysis with a row of “tomb-stone” appearance of basal cells seen in PV helps differentiate this condition from subepithelial blistering diseases such as MMP and BLP. A second biopsy is to be studied by direct immunofluorescence (DIF) for PV, where the test will demonstrate the presence of Igs, predominantly IgG in conjunction with complement component 3, IgA and IgM, in a “fish-net” appearance, in the intercellular spaces of affected oral epithelium.[2,13] Both the absence of an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder and deposition of IgG and complement along the dermal–epidermal junction in DIF helped in ruling out PNP. Indirect immunofluorescence is less sensitive than DIF.[14]

Vital to patient management is an early diagnosis, when lower doses rendered for shorter periods can effectively control the disease. Treatment is administered in two phases: a loading phase, to induce disease remission, and a maintenance phase, which is further divided into consolidation and treatment tapering.[12] Depending on the response, the dose is gradually decreased to the minimum therapeutic dose, taken once daily to minimize side effects. The cornerstone of therapeutic approach is systemic and/or local corticosteroid therapy. Systemic prednisolone (1–2 mg/kg/day), with or without topical betamethasone, beclometasone, or triamcinolone acetonide should be initiated immediately. Pulsed therapy, such as intravenous dexamethasone–cyclophosphamide pulse therapy, has been used in the management of recalcitrant lesions. As adjuvant therapy, immunosuppressive steroid-sparing agents commonly used are azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, intravenous Ig, and rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, with extreme cases requiring plasma exchange, and extracorporeal photopheresis references.[15]

Conclusion

Dental professionals must be familiar with clinical manifestation of PV. If not treated promptly, the disease has a high morbidity rate (5%–10%) in most of cases.[14] An effective treatment plan should be chalked out to enhance patients’ quality of life, with a sole motto of accelerated remission, few flare-ups, minimal hospitalization, and morbidity associated with therapeutic agents.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lever W. Pemphigus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1953;32:1–123. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajendran B. Diseases of the skin. In: Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM, editors. Shafer's Textbook of Oral Pathology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Noida; 2012. pp. 825–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pemphigus vulgaris and mucous membrane pemphigoid: Update on etiopathogenesis, oral manifestations and management. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3:e246–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madala J, Bashamalla R, Kumar MP. Current concepts of pemphigus with a deep insight into its molecular aspects. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:260–3. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_143_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seshadri D, Kumaran MS, Kanwar AJ. Acantholysis revisited: Back to basics. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:120–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.104688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amagai M, Tsunoda K, Zillikens D, Nagai T, Nishikawa T. The clinical phenotype of pemphigus is defined by the anti-desmoglein autoantibody profile. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:167–70. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spindler V, Heupel WM, Efthymiadis A, Schmidt E, Eming R, Rankl C, et al. Desmocollin 3-mediated binding is crucial for keratinocyte cohesion and is impaired in pemphigus. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30556–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grando SA. Cholinergic control of epidermal cohesion. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:265–82. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchenko S, Chernyavsky AI, Arredondo J, Gindi V, Grando SA. Antimitochondrial autoantibodies in pemphigus vulgaris: A missing link in disease pathophysiology. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3695–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seshadri D, Kumaran MS, Kanwar AJ. Acantholysis revisited: Back to basics. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:120–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.104688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagistan S, Goregen M, Miloglu O, Cakur B. Oral pemphigus vulgaris: A case report with review of the literature. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:359–62. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rai A, Arora M, Naikmasur VG, Sattur A, Malhotra V. Oral pemphigus vulgaris: Case report. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25:367–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed K, Rao TN, Swarnalatha G, Amreen S, Bhagyalaxmi Kumar AS. Direct immunofluorescence in autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders: A study of 59 cases. J NTR Univ Health Sci. 2014;3:164–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, Rigopoulos D. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: Challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521–7. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S75908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]