Abstract

Objective:

To study the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions toward evidence-based medicine among medical students from different colleges across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods:

An adapted evidence-based medicine (EBM) questionnaire was administered to second year to sixth year level of medical students and interns from different medical colleges across the Kingdom from November 2016 to May 2017. The questionnaire contains items that would describe the demographic characteristics of the respondents: 24 multiple-choice questions and one open-ended question. Questions were randomly arranged to refrain from respondents’ bias but are identified to determine the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of the respondents toward evidence-based medicine (EBP). Data were analyzed statistically using descriptive statistics.

Results:

This study surveyed 344 medical students from different universities in Saudi Arabia. The students’ knowledge and attitude to EBM were low: 80.8% answered incorrectly on the components of EBM; 40.4% knew that the strongest evidence to EBP is systematic review, and 95% of the respondents were not aware of the Cochrane Library (CL). Nearly 70% did not attend EBP workshops, 18% read journals, and 85.8% use the Internet to support clinical decisions. Only 50% are interested of knowing and using CL, 69.5% would evaluate the veracity of evidence when it contradicts clinical judgment, 24.4% will follow the evidence, and 6.1% will discard the evidence favoring their clinical judgment. No journal subscription, having no time, and difficulty in comprehension were the greatest reported barriers with a relative weight of 29.1%, 25%, and 15.7%, respectively; 68.8% claimed that EBP is not applicable to their culture, and 87.1% believed that their patients are willing to participate in clinical decision-making but perceived a low participation in clinical trials.

Conclusion:

The findings described the current status of the level of awareness and use of EBM among the medical students. This calls for a well-structured incorporation of the pedagogy into the undergraduate curriculum as a major competency standard considering culture and values that are well-preserved in the Kingdom. The outcomes of its integration will impact not only the medical and allied-medical professions but also the public health in general.

Keywords: Evidence-based medicine, Medical student, Saudi Abrabia

Introduction

Innovation in information technology alongside massive increase in biomedical research has given rise to a relentlessly changing biomedical literature varying in quality and clinical relevance. This has led to the emergence of evidence-based medicine (EBM) as the new paradigm for medical practice.[1]

EBM is defined as the “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence.”[2] It integrates individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence and uses individual patients’ values and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care.[3] The term “evidence-based medicine” entered the lexicon in 1992. Since then, it has become the latest focus in the search for improved health care.[4]

EBM has thus become an impetus for incorporating a critical appraisal of research evidence alongside routine clinical practice. Increasingly, the acquisition of knowledge and skills for EBM is becoming a core competence for all doctors. As a result of studies demonstrating substantial gaps between research evidence and the care provided in usual clinical practice,[5] there is an increasing emphasis on the teaching of EBM skills in undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing medical education programs.[6,7,8,9]

Although EBM encourages the use of primary research studies, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, and systematic overviews to inform treatment decisions,[10] recent surveys have suggested that most physicians still rely heavily on the opinion of colleagues or consultants when making these decisions. Although various barriers to the application of EBM principles in clinical practice have been described,[11,12,13] their relative importance to the practicing clinician is unknown.

Despite the many reported needs and demands, EBP implementation has remained a challenge for more than 20 years. Many studies have assessed the attitudes, knowledge, awareness, barriers, and potentials of EBP among the health professions and have reported varied results with limited success in developing a strong strategy for implementing EBP at the national and international levels.[14,15,16,17,18] From an educational perspective, EBP requires multiple high-level skills such as critical and logical thinking and analysis. It also requires clinical expertise to make judgments and decisions.

The practice of EBM involves four primary steps: formulating a clear question based on a patient problems, identifying relevant studies from the literature, critically appraising the validity and usefulness of the identified studies, and applying the findings to clinical practice.[11] Despite enthusiasm in the educational and research communities for EBM, limited research has been carried out among medical students across medical colleges in Saudi Arabia in terms of their knowledge, attitudes, and perception as seen in the literature. That is the aim of this investigation.

This research will help improve EBM in an undergraduate curriculum in different medical collages. It will emphasize the importance of applying EBM in making treatment decisions to provide the best medical care for patients at the lowest cost.

Materials and Methods

This was an analytic, cross-sectional survey conducted between November 2016 and May 2017. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed among medical students across Saudi Arabia. The main inclusion criterion was that the respondents have to be a medical student from second year to intern studying in a Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) university.

Survey instrument

This study adopted questionnaires from previous published studies[19,20] because these prior works have already been validated and can be used for an international comparison.

Data analysis

To capture the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of medical students on EBM, data were tallied on a frequency distribution table, and the responses were dichotomized to Yes or No. “Yes” if the respondent agrees to or is practicing the described items in knowledge, attitudes, and perception questions and “No” if the respondent believes otherwise. Frequencies were then reported in terms of the relative weight of the responses against the entire population.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

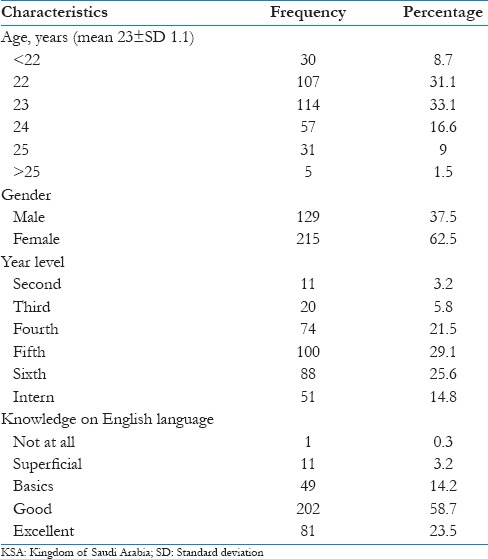

This study surveyed 344 respondents—all were medical students from different Saudi universities: fifth-year students were 29.1% (100), followed by sixth year, fourth year, interns, third year, and second year with a relative percentages of 25.6% (88), 21.5% (72), 14.8% (51), 5.8% (20), and 3.2% (11), respectively, and with a mean age of 23 years. Most respondents were female (62.5%) and with good knowledge on English language 58.7% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents of evidence-based medicine questionnaire from different universities in KSA (n=344)

Knowledge, attitude, and perception of the respondents

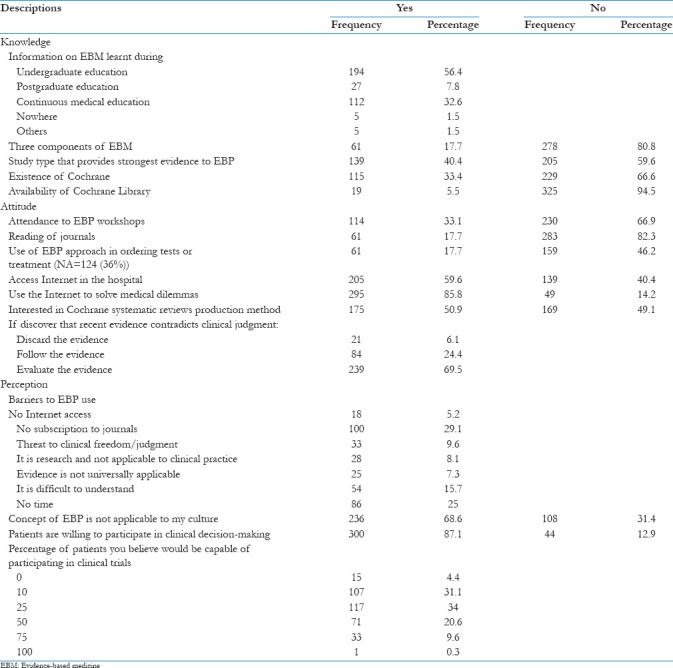

Table 2 shows that 56.4% of the respondents learned about EBM from their undergraduate education, while 32.6% learned from continuous medical education. However, when asked about the components of EBM, 80.8% answered incorrectly from the given choices, and only 40.4% knew that the strongest evidence to EBP is systematic review. It is alarming to note that almost 95% of the respondents were not aware of the Cochrane Library (CL)—it holds relevant databases to many cases that may be of use when a medical practitioner doubts the correct patient diagnosis and management.

Table 2.

Knowledge, attitudes, and perception of the respondents on the use of evidence-based medicine (n=344)

In addition, Table 2 reveals the attitude of the respondents in the use of EBM. Despite the fact that fifth-year and sixth-year medical students comprise the biggest proportion of the respondents, nearly 70% of them have not attended EBP workshops. Only about 18% of the respondents are reading journals perhaps because they do not have a journal subscription. When faced with medical dilemmas, 85.8% use the Internet—this is attributed to easy Internet access within the hospital premises. Despite the benefits that the CL could offer, only 50% are interested in knowing and using the library. However, it is very remarkable to note that 69.5% of the respondents would evaluate the veracity of evidence when it contradicts clinical judgment, 24.4% will follow the evidence, and 6.1% will discard the evidence and favor their clinical judgment.

The table further depicts the perceived barriers of the respondents on the use of EBM in their clinical practice. Students were given the following list of barriers: Internet access, subscription to journals, threat to clinical freedom, it is research and not applicable to clinical practice, evidence is not universally applicable, difficulty in comprehension, and no time. No journal subscription, having no time, and difficulty in comprehension were the greatest reported barriers with a relative weight of 29.1%, 25%, and 15.7%, respectively. When asked whether EBP is not applicable to their culture, 68.8% agreed to the statement with varying degrees (strongly agree, partially agree, and agree). Based on their experience in their clinical exposures, 87.1% of the respondents believed that their patients are willing to participate in clinical decision-making; 34% of the respondents thought that 25% of their patients would be willing to participate in clinical trials. Moreover, 4.4% of respondents thought that no patients would participate in the trials.

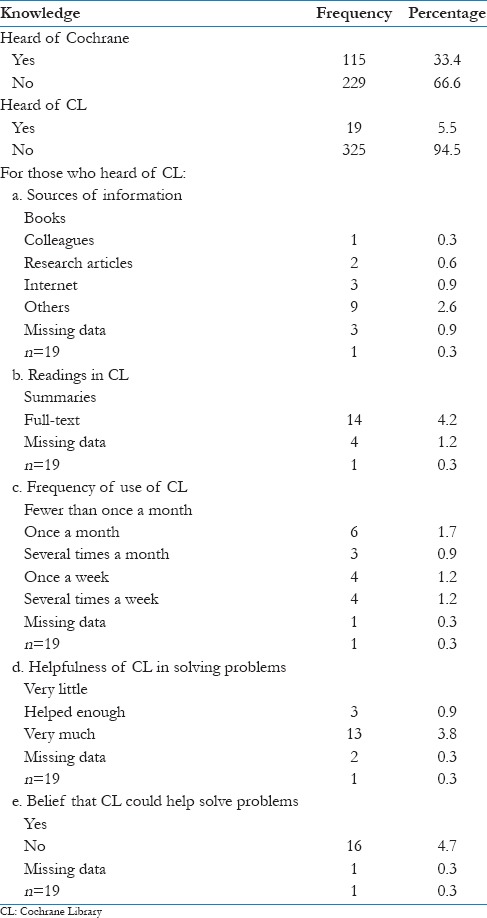

We asked the 5.5% of respondents who had heard about the CL answer questions 15–19 in the questionnaire [Table 3]. As to their source of information, 2.6% said the Internet; other sources include research articles, their colleagues, and books. Table 3 also depicts that 4.2% are reading summaries and only 1.2% are reading full-text articles with a frequency of fewer than once a month, 1.7% read several times, and 1.2% read once a week. Most respondents who had heard of the CL claimed it has helped them and believe that CL can help solve clinical problems.

Table 3.

Knowledge of the respondents on use of Cochrane and Cochrane Library (n=344)

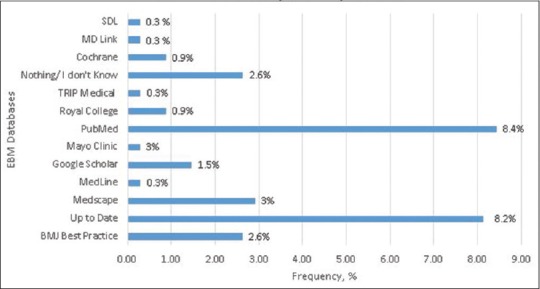

EBM databases

The respondents were asked an open-ended question as to the EBM databases that they use and are familiar with. Of the 344 respondents, only 101 (29.3%) answered the question as presented in Figure 1. From the 101 respondents, 8.4% are using PubMed Central and 8.2% are using Up to Date. Other databases that the respondents are familiar with include Cochrane, MedLine, Medscape, BMJ Best Practice, Google Scholar, Mayo Clinic, Royal College, Trip Medical, and the Saudi Digital Library. However, except for Cochrane, some of these tools do not offer systematic reviews of cases that may be of help in clinical decision-making. It is also important to note that 2.6% admitted that they know nothing about EBM databases.

Figure 1.

EBM databases used by respondents

Discussion

This study described the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of medical students from different colleges in the KSA on EBM. While it was the intent of the researchers to differentiate the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of the respondents as a function of training year, the sample size of some years is not sufficient for statistical comparisons and generalization; hence, we studied the data collectively and described the variables as one population of medical students across the Kingdom.

The data suggest that EBM is not popular among our cohort—only a small percentage knew about this pedagogy, its components, and the study type that provides strong evidence, that is, the Cochrane database and CL. The result impacts instruction in Saudi medical schools because most current medical curriculum introduces and incorporates EBM.[20] A study in 2014 compared senior dental and medical students in western Saudi Arabia and seemingly corroborates these finding: dental students were more knowledgeable than medical students,.[20] which may be attributed to the dynamic incorporation of EBM in the dental curriculum. While we did not seek to compare the medical curriculum across different medical colleges in the Kingdom, there is lack of utilization of the EBM principles, and this may explain the low level of knowledge among medical students. The EBP has shifted from the ability to critically appraise the literature into a key indicator or competency standard for measuring high-quality patient-oriented clinical care strategies. This trend has been developed and mandated by health organizations such as the National Health Service; it is part of the auditing process and is called clinical governance.[21] Educational institutions are the backbone of success in EBM implementation within the proposed framework. Studying the trends in behavioral changes and competencies among new graduates as part of the outcome assessment of curriculum reforms will guide educators in understanding the needs for educational changes to meet the changing needs of the workforce.[22] The modern medical curriculum is facing many challenges to cope with the high level of skills required by a competent current practitioner.

The overall general knowledge and attitude of the respondents to EBP is substandard to the competency standards that minimally call for skills in critically appraising the evidence.[23] The students in this study reported low attendance in EBP courses and poor follow-up in the literature. Fedorowicz et al.[24] showed that a higher percentage (39%) of dental and medical student respondents were reading dental journals. Nearly 40% of medical students did not use EBP in ordering tests or treatment. Those attitudes may explain their limited awareness of the importance of implementing EBP into their clinical practice. Although the undergraduate medical curriculum in most medical schools has incorporated EBP as a major competency standard for several years, the knowledge level seen here does not reflect this. Further assessment of the undergraduate curriculum from multiple perspectives including assessing teaching strategies, clinical settings, educator's qualifications for EBP, and so on is needed.

Here, only ∼18% identified the three components of EBP. The limited awareness of the students in identifying “patient's choice” as a main component of EBP needs to be highlighted. Similar surveys reinforced this lack of full awareness of the components of EBP among dentists. Improving such awareness should be highlighted in the undergraduate curriculum with more bedside practices to ensure cultural changes. Patient education might also be a possible strategy to support and promote an EBP cultural environment.[23]

The main barriers to the use of EBP, as reported in this study, were no subscription to journals, having no time, and difficulties in understanding the concept or subject. This finding was inconsistent with Fedorowicz et al.[24] wherein limited access to EBP resources was reported as the major issue followed by lack of time. The issue of time availability is complex and is often attributed to clinical overload.[25] Most respondents belong to the fifth- and sixth-year levels, and their clinical requirements might underlie their attitudes to EBP use/interest. Internet access was not noted as a major barrier in this study—there has been a dramatic increase in information technology in the KSA in the past 10 years. Currently, almost any healthcare professional can access relevant information.

Although the study did not dissect the cultural barriers in depth, the results show that almost 70% agree that EBP is not applicable to Saudi culture with responses varying from strongly agree, partially agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree. Almost 90% of the respondents believe that the clear majority of their patients can participate in clinical decision-making, although a smaller percentage felt that patients are willing to be involved in clinical trials.

A relevant literature search revealed that multiple research agencies claim that the incorporation of EBP competencies into healthcare system expectations and operations can drive higher quality, reliability, and consistency of healthcare and reduce costs.[23,24,25] However, the current research experience indicates that without a well-designed strategy for the integration of EBP into any clinical settings, the outcome is unpredictable and might not be worth the effort. The EBP requires an inte-professional approach and collective competency skills, knowledge, and clinical expertise.[26] It also requires a cultural change and awareness at various organizational levels: patient care and education; education of health professions; the availability of EBP specialists, resources, and centers; and the increased role of policymakers and managers in supporting the implementation of EBP.

The reported knowledge levels, attitudes, and perceptions seen here reflect the lack of evidence-based oriented clinical practice as part of the undergraduate clinical training in KSA medical schools, although the majority said they have heard about EBM during their undergraduate years. These findings highlight the urgent need for changes in the current educational strategies in Saudi Arabia. Searching the evidence and critically appraising it are important competency skills required by the undergraduate students and should be well-designed in the curriculum. Teamwork and interprofessional skills are also becoming important competency skills in implementing EBP.[23] Separating theory from practice will never assure behavioral and attitude changes and can be a recommendation for educational curriculum reform. Further research is needed to develop and validate tools to assess EBP competencies in the undergraduate curricula. Workforce settings should also be assessed.

Conclusion

The results described the current status of the level of awareness and the use of EBM among medical students. This calls for a well-structured incorporation of pedagogy into the undergraduate curriculum as a major competency standard. This standard should consider the culture and values of the Kingdom. The outcomes of its integration should impact not only the medical and allied-medical professions but also public health. Moreover, the information generated here supports the call of previously published studies challenging Saudi Arabia's medical curriculum to introduce, implement, and evaluate EBP.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guyatt GH, Meade MO, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Haynes RB. Practitioners of evidence-based care. BMJ. 2000;320:954–55. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. ACP J Club. 2002;136:A11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Furberg CD. From knowledge to practice in chronic cardiovascular disease: A long and winding road. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1738–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Board of Internal Medicine Self-Evaluation of Practice Performance. 2005. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.abim.org/moc/sempbpi.shtm .

- 7.Association of American Medical Colleges. Report II – Contemporary Issues in Medicine: Medical Informatics and Population Health. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACGME. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Outcome Project: General Competencies. 2006. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.acgme.org .

- 9.Greiner AC, Knebel E. Institute of Medicine. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers I, Dickersin K, Chalmers TC. Getting to grips with Archie Cochrane's agenda. BMJ. 1992;305:786–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6857.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naylor CD. Grey zones of clinical practice: Some limits to evidence-based medicine. Lancet. 1995;345:840–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92969-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Muir Gray JA. Transferring evidence from research into practice, 4: Overcoming barriers to application. ACP J Club. 1997;126:A14–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgers JS, Cluzeau FA, Hanna SE, Hunt C, Grol R. Characteristics of high-quality guidelines: Evaluation of 86 clinical guidelines developed in ten European countries and Canada. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:148–57. doi: 10.1017/s026646230300014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cluzeau FA, Burgers JS, Brouwers M, Grol R, Makela M, Littlejohns P, et al. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: The AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCaughey D, Bruning NS. Rationality versus reality: The challenges of evidence-based decision making for health policy makers. Implement Sci. 2010;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiffman RN, Shekelle P, Overhage JM, Slutsky J, Grimshaw J, Deshpande AM. Standardized reporting of clinical practice guidelines: A proposal from the Conference on Guideline Standardization. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:493–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwolsman S, te Pas E, Hooft L, Wieringa-de Waard M, van Dijk N. Barriers to GPs’ use of evidence-based medicine: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e511–21. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X652382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straus SE, McAlister FA. Evidence-based medicine: A commentary on common criticisms. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;163:837–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahammam MA, Linjawi AI. Knowledge, attitude, and barriers towards the use of evidence-based practice among senior dental and medical students in western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:1250–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majid S, Foo S, Luyt B, Zhang X, Theng YL, Chang YK, et al. Adopting evidence-based practice in clinical decision making: Nurses’ perceptions, knowledge, and barriers. J Med Libr Assoc. 2011;99:229–36. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.99.3.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang LA, Teich ST. A critical appraisal of evidence-based dentistry: The best available evidence. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;111:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnyk BM, Gallagher-Ford L, Long LE, Fineout-Overholt E. The establishment of evidence-based practice competencies for practicing registered nurses and advanced practice nurses in real-world clinical settings: Proficiencies to improve healthcare quality, reliability, patient outcomes, and costs. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11:5–15. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fedorowicz Z, Almas K, Keenan J. Perceptions and attitudes towards the use of evidence-based dentistry (EBD) among final year students and interns at King Saud University, College of Dentistry in Riyadh Saudi Arabia. Braz J Oral Sci. 2004;3:470–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ubbink DT, Guyatt GH, Vermeulen H. Framework of policy recommendations for implementation of evidence-based practice: A systematic scooping review. BMJ Open. 2013;24:3. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitto S, Grant R. Revisiting evidence-based checklists: Interprofessionalism, safety culture and collective competence. J Interprof Care. 2014;14:1–3. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.916089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]