Abstract

Auditory Verbal Hallucinations (AVHs) are commonly associated with psychosis but are also reported in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Hearing voices after the experience of stress has been conceptualised as a dissociative experience. Brewin and Patel’s (2010) seminal study reported that hearing voices is relatively common in PTSD, as hearing voices was associated with PTSD in half and two thirds of military veterans and survivors of civilian trauma, respectively. The authors conceptualised these voices as “auditory pseudohallucinations.” To build upon this work, we administered Brewin and Patel's’ interview to adult survivors (n = 40) of physical and sexual trauma with chronic PTSD, and healthy controls (n = 39). In contrast to previous findings, only 5% (n = 2) of our PTSD sample reported recently hearing a voice that was consistent with an auditory pseudohallucination, with no reports in our control group. Thus, no support was provided for auditory pseudohallucinations as a significant symptom in this population.

Keywords: Auditory verbal hallucinations, Pseudohallucinations, Hearing voices, PTSD, Dissociation

Highlights

-

•

5% of survivors of repeated physical and sexual trauma reported auditory pseudohallucinations.

-

•

PTSD from childhood trauma was not more strongly associated with auditory pseudohallucinations.

-

•

Co-morbid depression did not influence the experience of auditory pseudohallucinations.

1. Background

Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) can be defined as the experience of hearing a voice in the absence of an appropriate external stimulus (Stanghellini & Cutting, 2003). However, the conceputalisation of AVHs and the extent to which hearing voices can be considered phenomenologically independent from other intrusive, unwanted and/or unintended cognitions, has been a matter of enduring academic and clinical debate (e.g., Aleman & Larøi, 2008; Slade & Bentall, 1988). AVHs are commonly associated with psychosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and are recognised as a frequent source of distress and interference with functioning. As a result, AVHs are a major target of pharmacological interventions (Shergill, Murray, & McGuire, 1998) and psychological therapies (Thomas et al., 2014) for psychosis. However AVHs have also been identified in other disorders (Pilton, Verese, Berry & Bucci, 2015), where the experience of voices can impede therapeutic efficacy. Consequently, there are recommendations for tailoring existing therapeutic interventions (such as cognitive behaviour therapy; CBT) specifically for the treatment of AVHs (e.g. Smailes, Alderson-Day, Fernyhough, McCarthy-Jones, & Dodgson, 2015). Although other types of (pseudo)hallucinatory experiences, such as visual and olfactory hallucinations have been described in individuals with severe PTSD (e.g. Hamner, 1997; Hamner, Frueh, Ulmer, & Arana, 1999), the focus of the current study was on the experience of hearing voices.

In non-psychotic conditions, AVHs are most commonly reported in cases of combat-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (David, Kutcher, Jackson, & Mellman, 1999; Hamner et al., 1999; Seedat, Stein, Oosthuizen, Emsley, & Stein, 2003). Prevalence rates of AVHs in combat-related PTSD range from 20% to 58% (Brewin & Patel, 2010; David et al., 1999; Hamner et al., 1999; Ivezic, Bagariæ, Oruè, Mimica, & Ljubin, 2000; Seedat et al., 2003). Studies with civilian samples have been much less common. Anketell et al. (2010) evaluated a mixed sample of general psychiatric outpatients and those who had experienced conflict-related trauma and found that 50% of their sample with chronic PTSD reported AVHs. Similarly, Brewin and Patel (2010) suggested that AVHs are reported by a remarkable 67% of a civilian sample with PTSD.

This suggested preponderance of AVHs in sufferers of PTSD runs counter to clinical descriptions of the disorder. AVHs are not included as a criterion in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) criteria for PTSD, nor are they included as a key focus of treatment in any of the current evidence-based interventions for PTSD (i.e., eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing [EMDR], trauma-focused CBT, prolonged exposure, and cognitive processing therapy [CPT])). If AVHs are indeed a common and central component of the phenomenology of not only combat-related but civilian PTSD then this would have important nosogolical and therapeutic implications. Given this, the nature of AVHs in PTSD and the frequency of their experience in community PTSD samples is in need of further investigation and that is the focus of the present study.

A critical question is whether AVHs in PTSD are better conceptualised as pseudohallucinations linked to dissociative states, rather than as psychotic symptoms. Strong links between psychotic symptoms, including AVHs, and dissociative experiences have been demonstrated in a number of studies, in both clinical and non-clinical populations (see Moskowitz, Barker-Collo, & Ellson, 2004 for review). Allen, Coyne, and Console (1997) argued that dissociative detachment deprives individuals of “internal and external anchors”. The absence of anchors is proposed to increase an individual's sense of feeling disconnected from the world, interpersonal relationships, and within their intrapersonal self, resulting in a sense of confusion and disorientation, and critically, in an impairment in reality-testing. In this way, Moskowitz and Corstens (2007) proposed that for individuals hearing voices when exposed to high levels of stress, AVHs should be conceptualised as dissociative experiences. Similarly, Longden, Madill, and Waterman (2012) proposed that voices could be conceptualised as dissociated or ‘disowned components of the self’, arising from the failure to integrate adverse and traumatic sensory and psychological experiences into the context of the self. Hallucinatory experiences might therefore reflect directly or indirectly dissociated traumatic content (e.g., the voice of an abuser) impinging on conscious awareness (e.g. Anketell et al., 2010), rather than a psychotic symptom.

Indeed, prior research has demonstrated a strong correlation in veterans with PTSD between hearing voices and other dissociative experiences both in the present and at the time the traumatic event occurred (Brewin & Patel, 2010). Wearne, Curtis, Genetti, Samuel, and Sebastian (2017) also showed that dissociative experiences (including depersonalisation and derealisation) were a better predictor of AVHs than a diagnosis of PTSD. Both theory and prior research therefore suggest that the experience of AVHs in PTSD may be better understood as a dissociative experience and thus conceptualised as ‘pseudohallucinations’ and we shall use this term for the rest of the current article. A focus of the present study was therefore on the association between the experience of such pseudohallucinations and other dissociative symptoms.

For those experiencing civilian PTSD this raises the question of whether particular types of trauma exposure or trauma history are more or less likely to be associated with the experience of pseudo-hallucinations, as we know that dissociation is differentially associated with particular profiles of trauma exposure (Briere, 2006). The experience of childhood sexual abuse, has been established as a predictor of pseudohallucinations in samples both with and without psychosis (Hammersley & Fox, 2006; McCarthy-Jones, 2011; Read, McGregor, Coggan, & Thomas, 2006; Wearne et al., 2017), although the properties of the voices in these populations do not appear to differ between those with and without CSA (e.g. Offen, Waller, & Thomas, 2003). For this reason, the present study focused on a civilian sample presenting with PTSD following sexual assault, abuse or violence either in childhood or adulthood. We reasoned that the predicted high incidence of dissociation in this population would mean that the clinical presentation should include pseudohallucinations if such experiences are indeed a prevalent symptom in civilian samples. This population also allowed us to elucidate putative associations between pseudohallucinations and trauma in childhood.

Hamner and colleagues (Hamner, 1997; Hamner et al., 1999) have also suggested that pseudohallucinations in PTSD might be best accounted for as a function of comorbid depression. Since depression is not typically associated with high levels of dissociation, Brewin and Patel (2010) proposed that finding high levels of pseudohallucinations in a depressed sample would argue against their being a dissociative phenomenon. In their study of civilians with PTSD, Brewin and Patel (2010) collected an additional depressed sample without a primary diagnosis of PTSD. They found that 10% of the depressed sample reported the experience of pseudohallucinations and that these individuals scored in the low range on dissociative measures.1 From this, Brewin and Patel (2010) concluded that pseudohallucinations were not a function of comorbid depression but likely to be an aspect of dissociation. However, showing that pseudohallucinations do not characterize individuals with depression is not the same as investigating the role of comorbid depression in those with PTSD. In the present study, we therefore evaluated the relationship between depression comorbidity and pseudohallucinations in our community PTSD sample.

In sum, using both a self-report measure of dissociative experiences and a semi-structured interview to assess pseudohallucinations in trauma survivors (Brewin & Patel, 2010), we sought to determine if the prevalence of pseudohallucinations in a British sample of adult survivors of repeated physical and sexual trauma was as high as reported in the two previous studies with civilian samples (Anketell et al., 2010; Brewin & Patel, 2010). We also aimed to determine whether the frequency of pseudohallucinations was associated with the experience of childhood versus adult trauma. Finally, we aimed to explore the nature of pseudohallucinations by determining if their experience was associated with other dissociative symptomatology and with the experience of comorbid depression.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Ethics approval was obtained from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (reference 11/H0305/1). We recruited adults (aged 18–62) with a current diagnosis of chronic2 PTSD (n = 40) according to the DSM-IV (APA, 2013), following a history of sexual, physical and/or emotional abuse (as Criterion A events), and a healthy control group with no history of disordered mental health (n = 40), as determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, & Janet, 1996). Fifteen of the PTSD participants were recruited from the Haven – A Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) in Paddington. They were invited to take part following attendance at the Haven follow-up clinic or during an assessment for counseling or psychological therapy. Twenty-five of the PTSD participants and all of the control participants were recruited from the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit Volunteer Panels –databases of some 2000 community volunteers who have agreed to help with psychological research. Volunteers were recruited to the panels via advertisements in local newspapers.

According to the SCID-I, 35 (88%) of the PTSD group were exposed to between two and ‘too many to count’ past traumatic experiences (‘Criterion A traumas’). Nineteen (47.5%) reported that they experienced trauma prior to the age of 18, with the remaining 52% having only experienced trauma during adulthood (allowing us to compare AVHs between those with and without childhood trauma histories). Thirty eight percent of the total sample had experienced sexual assault during adulthood. All participants met DSM-IV criteria for chronic PTSD occurring as a result of these traumatic experiences. Sixteen (40%) had a comorbid diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), as determined by the SCID-I. One control participant met criteria for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and was excluded.

2.2. Procedure and measures

Participants completed the measures in a single session, individually and face-to-face with the experimenter, in a quiet testing room. All participants completed the SCID-I, to derive diagnoses of PTSD and other Axis I disorders and to determine that criteria for Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders were not met. In addition, participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-I; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961 3) to assess current depression symptomatology, along with two measures of hearing voices – the Dissociative Experiences Scale II (DES-II; Item 27 focuses on hearing voices), and a semi-structured interview to assess hearing voices (Brewin & Patel, 2010).

Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES-II; Carlson & Putnam, 1993). The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II) is a 28-item self-report instrument and widely used clinical tool to measure dissociation. The DES-II has good validity and reliability, and good psychometric properties (Carlson et al., 1993; Carlson & Putnam, 1993). Hearing voices is included as Item 27 on the DES-II: “Some people sometimes find they hear voices inside their head that tell them to do things or comment on things they are doing. Circle a number (0–100) to show what percentage of time this happens to you.” This item is part of a subset of DES-II items (the Dissociative Experiences Scale-II Taxon; DES-T; comprising items 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 22 and 27) that differentiate individuals with pathological dissociation from those showing normal variation in dissociative experiences (Waller, Putnam, & Carlson, 1996).

Auditory Pseudohallucinations Interview (Brewin & Patel, 2010). The Auditory Pseudohallucinations Interview was administered to all PTSD and control participants. This measure was taken from prior evaluations of pseudohallucinations (Brewin & Patel, 2010). To our knowledge, this measure has not been used in any other published studies. We administered the semi-structure interview in its entirety, as used by Brewin and Patel (2010).

The interview asked "Have you been aware in the past week of a stream of thoughts that repeats a very similar message over and over again inside your head? Sometimes the thoughts may just comment, or give instructions, or say if something is good or bad”. If participants responded yes, they were asked "Do you experience this as a voice or as a stream of thoughts?4″ If identified as a voice, details of up to three separate voices were recorded, including gender, whether it was a voice they recognised, how the voice referred to them, how often they currently heard the voice, when they had first noticed the voice, whether the voice related in any way to a past traumatic experience and the extent to which the voice seemed real (i.e., like someone was actually speaking to them). Participants described what the voice typically said and rated the effect of hearing the voice on a five-point scale for the extent to which they a) believed the content, b) could disagree with the voice, and c) could control the voice. Finally, again using five-point scales, they were asked to rate the extent to which encouraging, critical, happy, angry, rational, intimidating, supportive, and strong described each voice.

3. Results

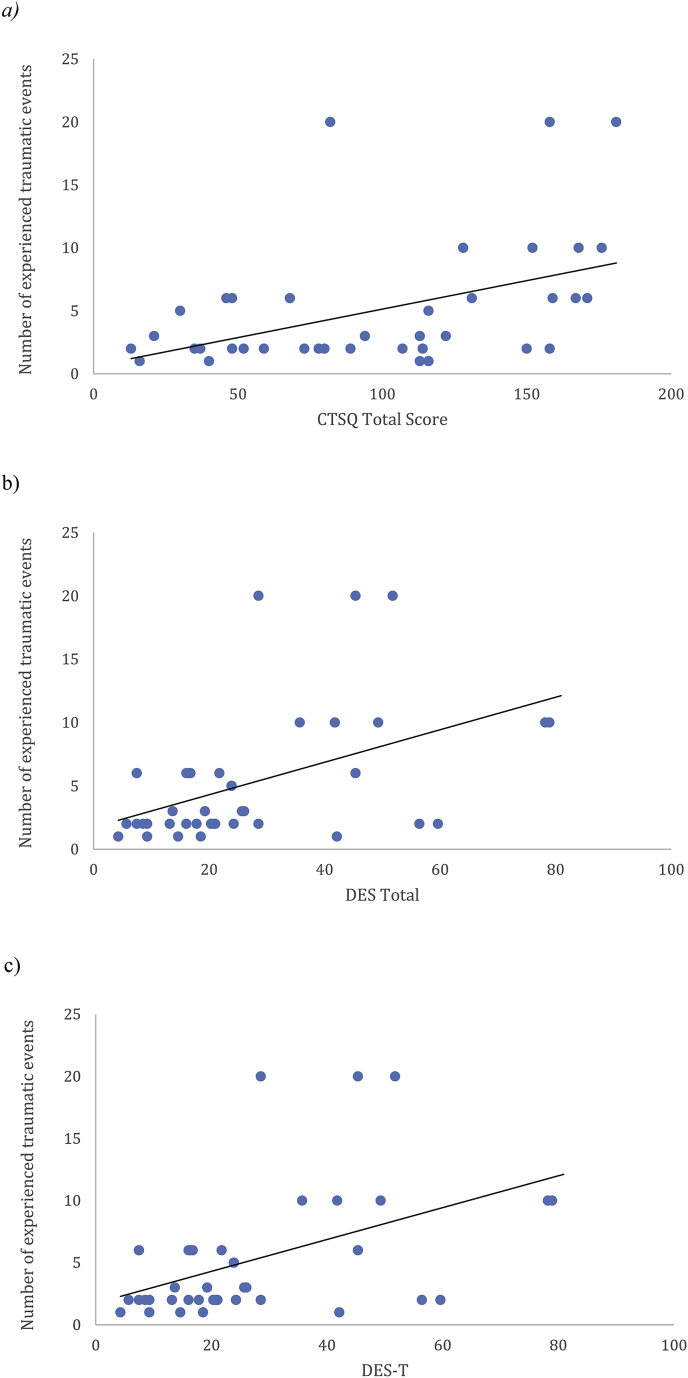

Demographic and symptom data are presented in Table 1. We observed the expected between-group difference in BDI-I scores. The control group were younger and more educated than the PTSD group, thus these variables were covaried in analyses. All results remained the same when the participants who had only experienced one trauma (n = 5) were removed from analyses, and data were re-analysed including only those who had experienced repeated traumas. The relationship between the number of experienced traumatic events and the key outcome measures is presented in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Mean (standard deviation) clinical Characteristics of PTSD Participants and Controls.

| PTSD Group (n = 40) | Control Group (n = 39) | Statistical Test | Effect Size (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years in Education | 14.15 (2.54) | 17.03 (1.90) | t(70.37) = 5.78, p < .001 | |

| Age (in years) | 34.40 (12.35) | 28.95 (8.22) | t(67.39) = 2.33, p = .02 | |

| Beck Depression Inventory score | 27.10 (12.59) | 3.46 (6.16) | t(55.39) = 10.42, p < .001 | |

| Dissociative Experiences Scalea (DES-II) score | 26.80 (18.95) | 5.41 (6.04) | F(1, 75) = 22.03, p < .001 | 0.54 |

| DES-II Item 27 (hearing voices) score | 13.00 (25.34) | 0.00 (0.00) | F(1, 75) = 6.36, p = .01 | 0.29 |

| DES-T score | 21.44 (19.36) | 1.85 (3.33) | F(1, 75) = 19.57, p < .001 | 0.51 |

DES-II analyses covaried age and education.

Fig. 1.

a) Relationship between the Number of Experienced Traumatic Events and the Complex Trauma Symptoms Questionnaire (CTSQ) Total Score for the PTSD Group (n=40). b) Relationship between the Number of Experienced Traumatic Events and the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II) Total Score for the PTSD Group (n=40). c). Relationship between the Number of Experienced Traumatic Events and the Dissociative Experiences Scale Taxon (DES-T) for the PTSD Group (n=40).

DES-II data. DES scores across groups are also displayed in Table 1. As can be seen from the table, ANCOVAs including age and education as covariates comparing the PTSD and control groups revealed significant group differences on the DES-II, DES-T and DES Item 27, with the PTSD group scoring significantly higher on all indices. Scores on Item 27 were strongly correlated with the sum of the remaining DES-T items, r (38) = 0.68, p < .001.

Within the PTSD sample, 13/40 (32.5%) answered positively (reported hearing voices >10% of the time) to Item 27. This contrasts with 48.4% of Brewin and Patel's (2010) veteran sample. None of the controls endorsed this item.

Those within the PTSD group reporting childhood trauma (n = 19) scored significantly higher on the DES-II (M = 33.31, SD = 22.52), t(36) = 2.32, p = .03, and on the DES-T (M = 27.04, SD = 23.33), t(36) = 2.08, p=.05, than those reporting trauma only in adulthood (n = 21; DES-II: M = 19.55, SD = 12.57; DES-T: M = 14.47, SD = 12.22). However, critically, there was no support for a difference between groups on Item 27 (childhood: M = 11.58, SD = 25.44; adulthood: M = 11.05, SD = 22.08), t(36) = 0.07, p = .95, d = 0.02, where the effect size was trivial (Cohen, 1992.

There were positive significant correlations between the DES-T scores and the total score on the CTSQ, r(38) = 0.64, n = 40, p < .001and the BDI, r(38) = 0.45, n = 40, p = .004) for the PTSD group.

Sixteen (40%) participants with PTSD also had a diagnosis of MDD. Scores on the DES-II did not significantly differ between those with (DES-II: M = 28.48, SD = 17.20; DES-T:M = 23.52, SD = 17.97; Item 27: M = 11.25, SD = 26.05) and without (DES-II: M = 25.67, SD = 20.31; DES-T: M = 20.05, SD = 20.50; Item 27: M = 14.17, SD = 25.35) comorbid MDD on the DES-II, t(38) = 0.46, p = .65, DES-T, t(38) = 0.55, p > .05, or Item 27, t(38) = -0.35, p = .73 and effect sizes were trivial (0.11 for DES-II, 0.12 for DES-T and 0.10 for Item 27)(Cohen, 1992).

Semi-structured interview. In response to the interview, 18/40 (45%) participants with PTSD reported having experienced a stream of thoughts in the past week. Of these, 11 (61.1%) had an MDD diagnosis and eight (44.4%) reported experiencing childhood trauma. However, only two (11.11%) of those participants reported hearing repetitive thoughts in the form of a voice speaking to them. Each had PTSD following childhood trauma (one had experienced sexual and one physical childhood abuse). This contrasts starkly with Brewin and Patel's (2010) finding of 67% of a heterogeneous civilian PTSD sample reporting voices on the same interview measure. Both participants here regarded the voice as a manifestation of their own thoughts (a “pseudohallucination”, Brewin & Patel, 2010). Each reported hearing one voice, which they recognised. One participant identified the voice as her father, who referred to her by name, and the other was identified as the female participant's own voice, which referred to them as ‘stupid bitch’ and was described as ‘talking to me like someone else would’. In both cases, the voice was heard ‘many times a day’. The effect of the voice was described as positive in one case (own voice) and negative in the other (father's voice). Both participants described the voice as having been present since childhood.

In the control group, 3/39 (8%) participants reported having experienced a stream of thoughts, but none identified these as a voice.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we sought to determine if the prevalence of auditory pseudohallucinations in a British sample of adult survivors of physical and sexual trauma with chronic PTSD was as high as reported in the two previous studies with civilian samples (Anketell et al., 2010; Brewin & Patel, 2010). We also aimed to determine whether the frequency of auditory pseudohallucinations was associated with the experience of childhood versus adult trauma. Finally, we aimed to explore the nature of auditory pseudohallucinations by determining if their experience was associated with other dissociative symptomatology and with the experience of comorbid depression.

In our PTSD sample, 32.5% answered positively (reported hearing voices >10% of the time) to Item 27 of the DES-II. When this question was presented within a semi structured interview, 45% of the PTSD group endorsed such experiences. However, when probed as to whether they experienced this “as a voice or a stream of thoughts”, only 2/40 (5%) of our sample of survivors of physical and sexual trauma reported recently hearing “a voice” that was consistent with an auditory pseudohallucination. This is significantly lower than the 67% of Brewin and Patel's (2010) PTSD sample, using the same semi-structured interview approach, and than the 50% reported by Anketell et al. (2010). None of our healthy control participants endorsed hearing voices on the interview measure nor on item 27 of the DES-II.

We also sought to evaluate the relationship of the experience of childhood trauma and of comorbid depression with the experience of hearing voices. However, as only two participants endorsed hearing voices, meaningful analyses were not possible. Of note, however, we found no support for differential endorsement of the relevant items on the DES for those with PTSD as a function of childhood trauma, or for those with PTSD and comorbid depression.

There are a number of factors which may have contributed to the discrepancy in endorsement of voices on the DES-II relative to the interview. A key difference between these measures is that during the interview the individual is required to explicitly distinguish between the endorsed experience being either a) a voice talking to them or b) a stream of thoughts, and the majority (all bar two) of the participants reported that it was a stream of thoughts. It is possible that the DES-II may capture rumination and internal self-talk, and thus the more fine-grained evaluation provided by the interview question may account for why the incident reduced from that reported in the DES-T. Of course, there is also the possibility that participants did not want to discuss the voice face-to-face with a clinician for fear of negative evaluation or discomfort, and thus more readily reported hearing voices in the self-report format but we feel this is unlikely given that participants had consented to take part in the study knowing that this was a focus. These issues will need to be addressed in future studies.

In our sample of adults with a history of repeated physical and sexual trauma, we therefore found no evidence to support the previously reported high prevalence rates of auditory pseudohallucinations in other PTSD samples assessed using similar interview measures. The question of course is raised as to why there should be such a discrepancy between our findings and previous work. One possibility is that auditory pseudohallucinations are not a feature, specifically, of PTSD populations who have experienced repeated sexual or physical interpersonal trauma. However, given the previous literature linking such trauma exposure to higher levels of dissociation (Briere, 2006) and to the experience of auditory pseudohallucinations in individuals with and without psychosis (Hammersley & Fox, 2006; McCarthy-Jones, 2011; Read, van Os, Morrison, & Ross, 2015; Wearne & Genetti, 2015), one would have predicted a priori a higher prevalence of AVHs in the present sample relative to a heterogeneous community sample of the kind evaluated by Brewin and Patel (2010). Another possibility is although auditory pseudohallucinations have been conceptualised in the literature as a distinct psychological symptom, they should instead be considered as an artefact of recurrent intrusive memories and the auditory re-experiencing of traumatic events. We found that 18/40 of our PTSD group reported having experienced a stream of thoughts but only two reported this was a voice speaking to them when probed by a clinician with extensive experience of working with complex PTSD populations. Perhaps only these two participants had found the metaphor of “hearing voices” to be a helpful way of explaining a recurrent intrusion.

A recent review (Steel, 2015) explored the relationship between hallucinations (including AVHs) and stressful or traumatic life events, with the reviewed studies indicating that there was a 12–40% overlap in the content of pseudohallucinations and traumatic memories The largest phenomenological survey of AVHs to date involved interviewing 199 voice hearers (McCarthy-Jones et al., 2014). Of these, 12% reported that they heard voices, which were identical replays of memories of previous conversations, whilst 31% reported that the relationship was similar but not identical. Similarly, studies reviewed by Steel (2015) suggested the presence of thematic links between prior trauma and the content of hallucinations. Steel (2015) concluded that the relationship between hallucinations and past traumatic experiences remains elusive, and thus is in need of further investigation. If AVHs are the auditory re-experiencing of past traumatic events then this has important implications for treatment; for example, the content of AVHs may represent hotpots that require rescripting in trauma-focused CBT and other similar interventions.

Limitations of this study include the specific focus on individuals with a chronic history of multiple incidences of sexual, physical and/or emotional abuse, rather than a broader inclusion of other, non-interpersonal traumatic experiences. As is common when working with survivors of repeated traumas, it was difficult to distinctly separate out different trauma types and their timing, especially with those who had experienced childhood trauma, and this therefore represents a methodological limitation. Our control and PTSD groups were also not matched for age and education level, although this turned out to be moot as there was minimal difference in our core construct of interest – endorsement of hearing voices in a semi-structured clinical interview. An additional limitation of the study was not including a formal measure of PTSD severity, such as the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995), although all participants did meet criteria for the Chronic PTSD specifier on the SCID.

In summary, in contrast to our predictions we found no support for a significant presence of auditory pseudohallucinations in a civilian sample of adults with chronic PTSD following sexual and/or physical interpersonal trauma. Our results suggest that prior reports of high prevalence of auditory pseudohallucinations in civilian samples are in need of further replication.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC; grant number SUAG/006/RG91365).

Footnotes

Below 30 on the Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES-II; Carlson & Putnam, 1993).

duration of symptoms is 3 months or more (APA, 2013).

The first version of the BDI was used for legacy reasons to do with the Department volunteer panels.

The wording of this question was changed from ‘Do you experience this as a voice or just as a stream of thoughts’ by removing the word ‘just’ as we were concerned that keeping it in implied that one was more important than the other.

References

- Aleman A., Larøi F. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2008. Hallucinations: The science of idiosyncratic perception. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.G., Coyne L., Console D.A. Dissociative detachment contributes to psychoticism and personality decompensation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1997;38:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90928-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Anketell C., Dorahy M.J., Shannon M., Elder R., Hamilton G., Corry M. An exploratory analysis of voice hearing in chronic PTSD: Potential associated mechanisms. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2010;11:93–107. doi: 10.1080/15299730903143600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Ward C.H., Mendelson M., Mock J., Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D.D., Weathers F.W., Nagy L.M., Kaloupek D.G., Gusman F.D., Charney D.S. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin C.R., Patel T. Auditory pseudohallucinations in United Kingdom war veterans and civilians with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71:419–425. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05469blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Dissociative symptoms and trauma exposure: Specificity, affect dysregulation, and posttraumatic stress. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:78–82. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198139.47371.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.B., Putnam F.W. An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation. 1993;6:16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.B., Putnam F.W., Ross C.A., Torem M., Coons P., Dill D.L. Validity of the dissociative experiences scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: A multicenter study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1030–1036. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.7.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D., Kutcher G.S., Jackson E.I., Mellman T.A. Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:29–32. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v60n0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M.B., Spitzer R.L., Gibbon M., Williams J.B., Janet B.W. American Psychiatric Press, Inc; Washington, D.C.: 1996. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders, clinician version (SCID -CV) [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley P., Fox R. Childhood trauma and psychosis in the major mood disorders. In: Larkins W., Morrison A., editors. Trauma and psychosis: New directions for theory and therapy. Routledge; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hamner M.B. Psychotic features and combat‐associated PTSD. Depression and Anxiety. 1997;5:34–38. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1997)5:1<34::aid-da6>3.0.co;2-5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1997)5:1<34::AID-DA6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamner M.B., Frueh B.C., Ulmer H.G., Arana G.W. Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:846–852. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivezic S., Bagariæ A., Oruè L., Mimica N., Ljubin T. Psychotic symptoms and comorbid psychiatric disorders in Croatian combat related post-traumatic stress disorder patients. Croatian Medical Journal. 2000;41:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longden E., Madill A., Waterman M.G. Dissociation, trauma, and the role of lived experience: Toward a new conceptualization of voice hearing. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138:28–76. doi: 10.1037/a0025995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy-Jones S. Voices from the storm: A critical review of quantitative studies of auditory verbal hallucinations and childhood sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:983–992. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy-Jones S., Trauer T., Mackinnon A., Sims E., Thomas N., Copolov D. A new phenomenological survey of auditory hallucinations: Evidence for subtypes and implications for theory and practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40:231–235. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz A., Barker-Collo S., Ellson L. Replication of dissociation-psychoticism link in New Zealand students and inmates. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;193:722–727. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000185895.47704.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz A., Corstens D. Auditory hallucinations: Psychotic symptom or dissociative experience? Journal of Psychological Trauma. 2007;6:35–63. doi: 10.1300/J513v06n02_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Offen L., Waller G., Thomas G. Is reported childhood sexual abuse associated with the psychopathological characteristics of patients who experience auditory hallucinations? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:919–927. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00139-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilton M., Varese F., Berry K., Bucci S. The relationship between dissociation and voices: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:138–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J., McGregor K., Coggan C., Thomas D.R. Mental health services and sexual abuse: The need for staff training. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2006;7:33–50. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J., van Os J., Morrison A.P., Ross C.A. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;112:330–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S., Stein M.B., Oosthuizen P.P., Emsley R.A., Stein D.J. Linking posttraumatic stress disorder and psychosis: A look at epidemiology, phenomenology, and treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:675–681. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000092177.97317.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shergill S.S., Murray R.M., McGuire P.K. Auditory hallucinations: A review of psychological treatments. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;32:137–150. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade P., Bentall R.P. 1988. Sensory deception: A scientific analysis of hallucination. (London: Croom Helm) [Google Scholar]

- Smailes D., Alderson-Day B., Fernyhough C., McCarthy-Jones S., Dodgson G. Tailoring cognitive behavioural therapy to subtypes of voice-hearing. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1933. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanghellini G., Cutting J. Auditory verbal hallucinations — breaking the silence of inner dialogue. Psychopathology. 2003;36:120–128. doi: 10.1159/000071256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel C. Hallucinations as a trauma based memory: Implications for psychological interventions. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1262. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01262. ISSN 16641078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N., Hayward M., Peters E., van der Gaag M., Bentall R.P., Jenner J. Psychological therapies for auditory hallucinations (voices): Current status and key directions for future research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40:202–212. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller N.G., Putnam F.W., Carlson E.B. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:300–321. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.3.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wearne D., Genetti A. Pseudohallucinations versus hallucinations: Wherein lies the difference? Australasian Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):254–257. doi: 10.1177/1039856215586150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearne D., Curtis G.J., Genetti A., Samuel M., Sebastian J. Where pseudo- hallucinations meet dissociation: A cluster analysis. Australasian Psychiatry. 2017;4:364–368. doi: 10.1177/1039856217695706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]