Abstract

Background:

Today, cancer care and treatment primarily take place in an outpatient setting where encounters between patients and healthcare professionals are often brief.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to summarize the literature of adult patients’ experiences of and need for relationships and communication with healthcare professionals during chemotherapy in the oncology outpatient setting.

Methods:

The systematic literature review was carried out according to PRISMA guidelines and the PICO framework, and a systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE, CINAHL, The Cochrane Library, and Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Based Practice Database.

Results:

Nine studies were included, qualitative (n = 5) and quantitative (n = 4). The studies identified that the relationship between patients and healthcare professionals was important for the patients’ ability to cope with cancer and has an impact on satisfaction of care, that hope and positivity are both a need and a strategy for patients with cancer and were facilitated by healthcare professionals, and that outpatient clinic visits framed and influenced communication and relationships.

Conclusions:

The relationship and communication between patients and healthcare professionals in the outpatient setting were important for the patients’ ability to cope with cancer.

Implications for Practice:

Healthcare professionals need to pay special attention to the relational aspects of communication in an outpatient clinic because encounters are often brief. More research is needed to investigate the type of interaction and intervention that would be the most effective in supporting adult patients’ coping during chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic.

KEY WORDS: Ambulatory chemotherapy, Communication, Coping, Healthcare professional–patient relation, Nurse-patient relation, Outpatient care, Patient perspective, Professional-patient interactions, Systematic review

In recent years, cancer care and treatment have shifted toward ambulatory services, fewer hospital admissions, and shorter hospital stays.1,2 Today, oncology treatments are primarily provided in outpatient settings.3–5 In general, international data on this development are not available. However, in Denmark, the overall number of outpatient treatments in public hospitals between 2006 and 2011 increased by 19%, and the number of hospitalization days during the same period decreased by 12%.6 For the past years, the goal of the national health policy in Denmark has been to reorganize the healthcare system so that patients are hospitalized only when there is no appropriate outpatient treatment available.7,8 This development continues internationally as the global cancer burden is growing significantly because of an increase in the world’s elderly population and the overall adoption of cancer-causing behaviors.9 Furthermore, the number of patients with cancer who require ambulatory chemotherapy is increasing.10,11 Although outpatient treatment leads to better cost control,7 efficiency can change the way care is given and overlook the key role the relationship with the healthcare professional (HCP) has for patients’ coping.12 At the same time, studies have suggested a possible risk of not identifying patients’ needs because of the limited time allotted.13,14 Research has clarified that the relationship between patients with diabetes and HCPs was central for patients’ ability to cope with their disease.15,16 In particular, patients with cancer need supportive and caring relationships with the HCP17,18 because cancer treatment often affects patients’ quality of life, even years after the diagnosis.19 A systematic review pointed out that patients with cancer often associated the term good nursing with their relationship to the nurse, and this was perceived as being important for the feeling of confidence and well-being.20 A qualitative study exploring nurses’ experiences of providing nursing care in a day hospital for patients with cancer identified barriers to establishing relationships.21 In particular, focus on administration of chemotherapy was experienced as a central barrier for a well-functioning nurse-patient relationship. In addition, the authors reported that research focusing on the needs of patients with cancer has mainly been carried out during hospitalization.21

Because of a growing trend in outpatient cancer management, focus on the encounters between patients and HCPs during oncology treatment has become increasingly important. Healthcare professional communication skills have been found to be increasingly vital in meeting the challenges within the healthcare system.22,23 Clinical guidelines are necessary for the development of evidence-based practice; however, current recommendations are primarily based on the HCPs’ perspective and, to a lesser extent, on the patients’ perspective, and they do not take into account the treatment setting and context, that is, outpatient.24 Patient experiences can help identify areas for improvement in cancer care,25,26 leading to gains in clinical quality27 and efficiency.28 Furthermore, the patients’ experience is a key factor in patient-centered care.28,29

Objective

To understand the meaning and impact of the encounter between the patient and the HCP in an oncology outpatient setting, this systematic review aimed to summarize the literature from the perspective of the patient on the experiences of and need for relationships and communication with the HCP during chemotherapy treatment in an outpatient setting.

Methods

Search Strategy

The literature review was planned and conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines30 and the PICO framework30,31 and based on a protocol. The systematic search was carried out in MEDLINE, CINAHL, The Cochrane Library, and Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Based Practice Database. The last search was performed on June 6 to 7, 2016. The search included MESH terms and keywords, and each keyword was combined with Boolean operators (and, or, not); truncation was used to expand the number of hits. Moreover, the reference lists of the included articles were hand searched,32 and no gray literature was included. The following is an example of a search string applied in PubMed: ((((neoplasms OR cancer)) AND (((“nurse patient relations” OR “professional patient relations” OR “psychosocial support” OR communication OR “supportive care” OR “nursing interaction”)) OR oncologic nursing)) AND (((outpatients OR “outpatient clinics” OR “day care” OR “ambulatory care” OR ambulatory OR “time factors” OR “time management” OR “short term stay” OR ”short encounters”)) OR ((“length of stay”) AND short))) AND (coping OR empowerment OR “sense of coherence” OR “quality of life” OR “sense of control” OR “patient satisfaction” OR “patient participation” OR “patients experience*” OR “patients expectation*”).

The inclusion criteria were studies that included adult patients with cancer (≥18 years old) undergoing cancer treatment (curative or palliative), receiving primarily intravenous chemotherapy in an oncology outpatient setting; we applied no time limitation. Studies that captured the patients’ experiences and needs and evaluation of “patient-HCP” interactions by individual interview, focus group interview, or patient-reported outcomes were included. Studies published in English, Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish were included. Excluded were studies taking place in the in-hospital setting, intervention trials, and questionnaire validation studies.

Data Collection

After eliminating duplicates, the first and second authors (A.P. and K.A.M.) screened the titles and abstracts for inclusion, and full-text copies were obtained when necessary. A.P. and K.A.M. independently assessed the identified studies for inclusion, and disagreements were resolved by discussion with the last author (A.K.D.). All studies meeting the inclusion criteria were subsequently read in full text and assessed for inclusion, and disagreements were settled among the entire author group.

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Studies

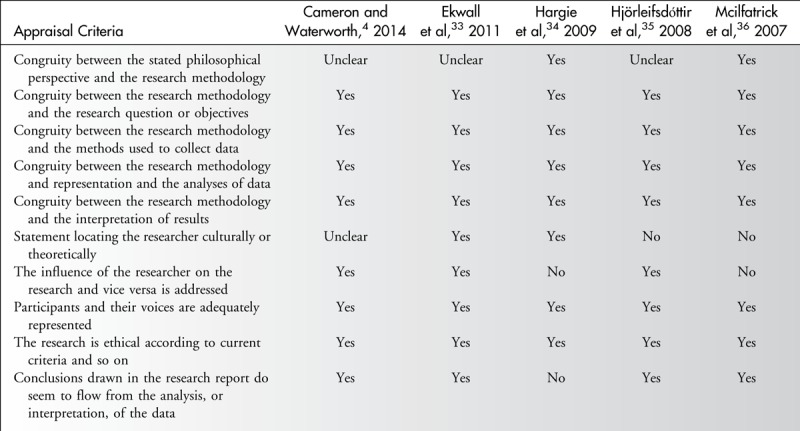

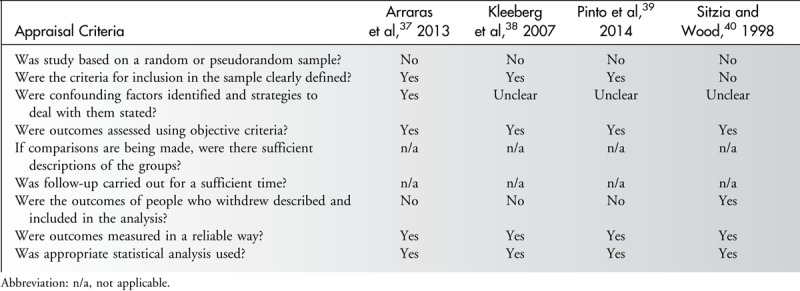

All included studies were critically appraised according to the Joanna Briggs Reviewer Manual31 using the critical appraisal tools: Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument for the qualitative studies (Table 1) and Meta Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument for the quantitative studies (Table 2).

Table 1.

Assessment of the Qualitative Studies: Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument

Table 2.

Assessment of the Descriptive Studies: Meta-analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument

Data Extraction

Data were extracted and assessed by 2 authors (A.P. and K.A.M.). Data from the qualitative and quantitative studies were extracted and assessed in parallel processes. Subsequently, we conducted an integrative synthesis summarizing data from the qualitative studies followed by the quantitative studies.41 Hereafter, we identified main findings across the included studies, and these results were presented as narrative summaries31,41 (Tables 3 and 4). The findings were extracted based on our aim, and only findings that elucidated our aim were reported.

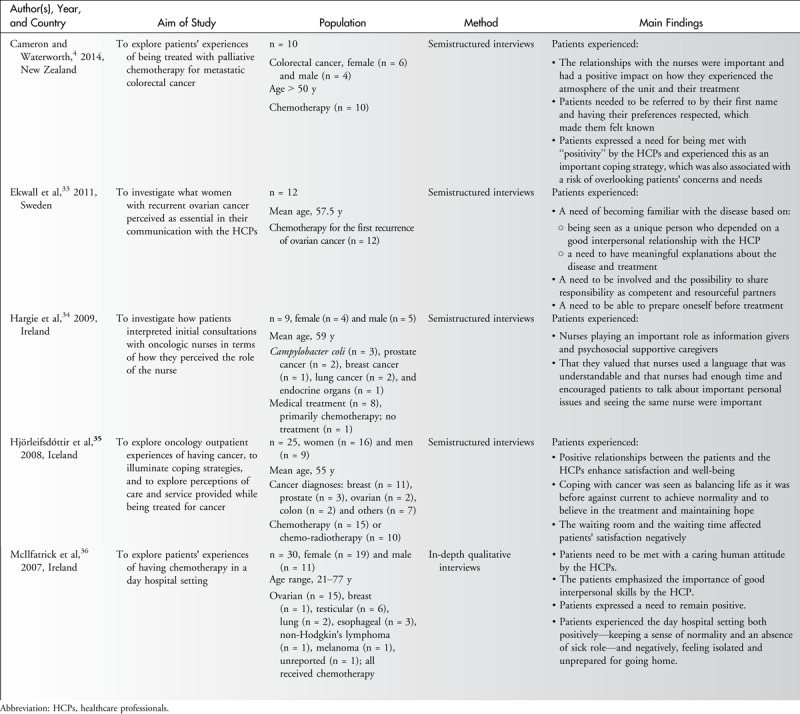

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Qualitative Studies

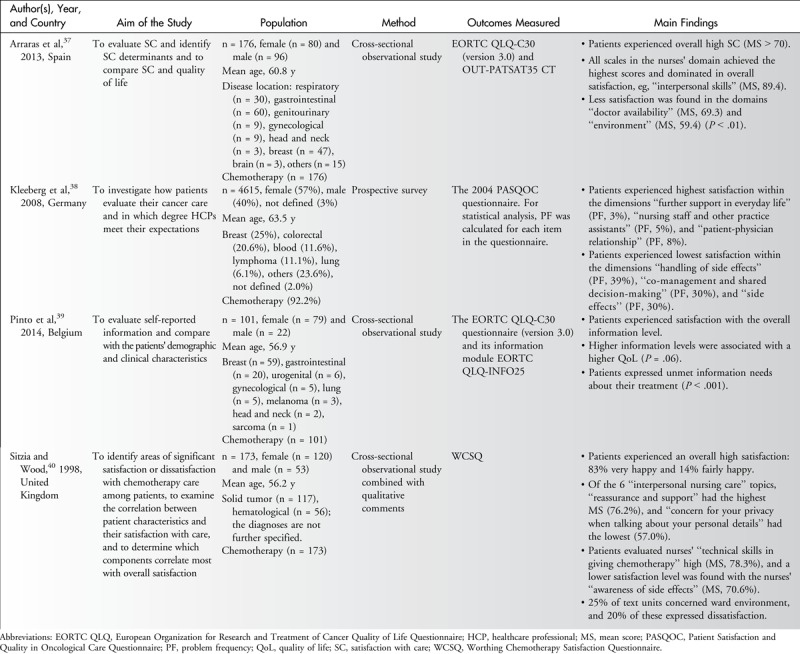

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Quantitative Studies

Results

Identification of Relevant Studies

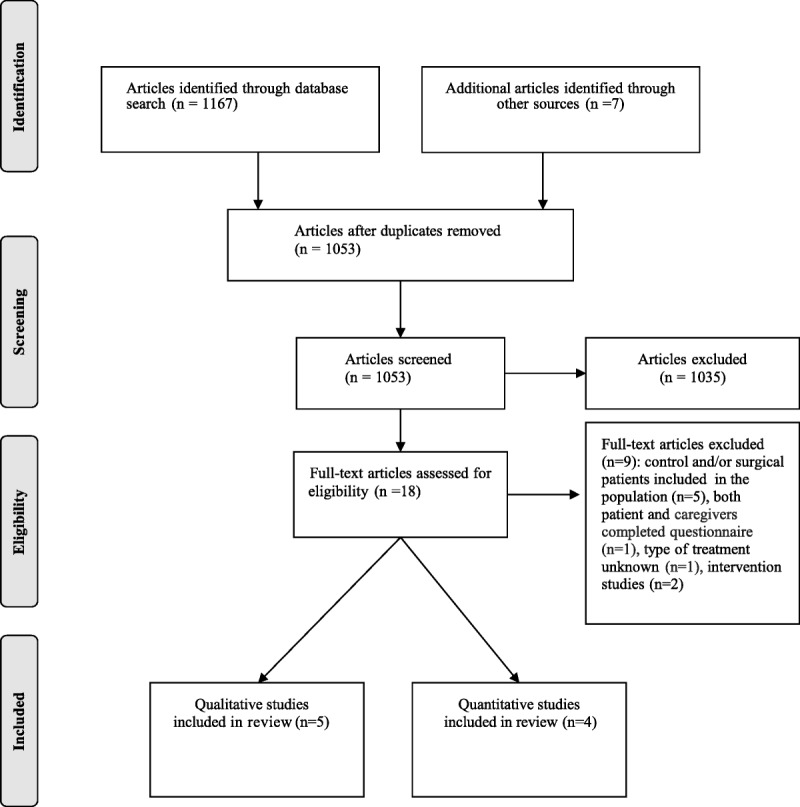

In all, 1174 studies were identified by literature search (n = 1167) and reference search (n = 7) (Figure). Once duplicates were removed, the remaining studies (n = 1053) were screened for inclusion. Furthermore, 1035 studies were excluded by title and abstract reading because of not fulfilling the inclusion criteria, and the remaining studies (n = 18) were read in full. Nine studies were excluded after full-text reading because they did not meet the population inclusion criteria. Of these, 5 studies included control and/or surgical patients not undergoing chemotherapy; 2 studies were intervention studies; in 1 study, both patients and caregivers had completed questionnaires; and, in 1 study, it was not clear which treatment the patients had received. Finally, 9 studies, 5 qualitative (Table 3) and 4 quantitative (Table 4), were included.

Figure.

Flowchart of the study retrieved and selection process.

Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 5050 patients were included in this review, 86 patients from the 5 qualitative studies and 4964 patients from the 4 quantitative studies. Both genders were represented, female (n = 2888) and male (n = 2024); 138 patients did not report their gender. The participants had mixed cancer diagnosis predominantly treated with chemotherapy. Eight of the studies were conducted in Europe—Belgium (n = 1),39 Germany (n = 1),38 Iceland (n = 1),35 Ireland (n = 2),34,36 Spain (n = 1),37 Sweden (n = 1),33 and United Kingdom (n = 1)40—and 1 study was conducted in New Zealand (n = 1).4

Data from the qualitative studies were collected by semistructured in-depth individual interviews4,33–36 (Table 3). Three quantitative studies37,39,40 used a cross-sectional observational study design with different measurement tools, and 1 study38 used a prospective survey (Table 4).

Assessment of the Methodological Quality

The assessment of the methodological quality was performed independently by A.P., K.A.M., M.J., and A.K.D. using Joanna Briggs critical appraisal tools,31 hereafter compared for consistency, and discussed until agreement was reached between the 3 authors and afterward in the entire author group.

The overall methodological quality of the qualitative studies was generally high in all 5 studies4,33–36 because they had congruity between the research question and methods for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data. Two studies scored 9 of 10,33,34 and 3 studies scored 8 of 104,35,36 (Table 1).

The methodological quality of the quantitative studies was rated slightly lower, although two of the appraisal criteria were not applicable and therefore not included in the overall assessment. One study scored 5 of 7 points,37 and 3 studies scored 4 of 7 points.38–40 No random or pseudorandom sampling strategy was applied in any of the included quantitative studies.37–40 Hence, Arraras et al37 recruited the first 3 eligible patients who were to receive chemotherapy on a given day, Kleeberg et al38 included patients consecutively, Sitzia and Wood40 included patients during a given period, and Pinto et al39 included 1 of 3 eligible. Nevertheless, they did not describe how the patients were selected. All studies had inclusion criteria, although the criteria presented by Kleeberg et al38 were interpreted through their presentation of exclusion criteria. All the quantitative studies applied appropriate and reliable statistical analysis including relevant correlation analyses.37–40 All studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in the review regardless of methodological quality.

Findings Emerging From the Studies

Across the 9 included studies, 3 main findings emerged that elucidated our aim: (1) the relationship between the patients and HCPs is important for the patients’ ability to cope and has an impact on satisfaction of care, (2) hope and positivity are a need and a strategy for patients with cancer and are facilitated by HCPs, and (3) outpatient clinic visits frame and influence communication and relationships.

The Relationship Between the Patients and HCPs Is Important for the Patients’ Ability to Cope With Cancer and Has an Impact on Satisfaction of Care

All studies found that patients reported that their interactions and relationships with the HCPs were associated with satisfaction with care.4,33–40 The qualitative studies4,34 and quantitative studies37,38 showed that nurses in particular played an important role for patients’ satisfaction with care.4,35 The patients’ encounters with the HCP were closely related to the treatment situation. A patient supported this: “It is undisputed that the behavior, caring encounters and encouragement of the doctors and nurses can influence the treatment, it is simple, I feel better and therefore it is easier for my body to do its job,[…]. I am certain, that these caring attitudes matter most, and I think the medical treatment comes next.”37(p520)

Central elements in forming the relationship between the HCP and the patient were highlighted including the importance of the HCP having good interpersonal skills,33,34 which included being a good listener,35 being trustful,35 having a compassionate attitude,36 and using a caring approach.35 In addition, patients valued being addressed by their first name, which made them feel recognized,4 and they appreciated the continuity of meeting the same HCP at each outpatient visit.33,35

Patients with cancer expressed a special need for good communication with the HCP in the outpatient clinic.33–35,38 Patients valued communication that was facilitated in a personal and meaningful way,33 for example, using eye contact33,36 and based on dialogue.33,36 Patients expressed a need for the HCP to have certain communication skills such as having a compassionate attitude along with the ability to convey information in an understandable language.4,33,34,36 Being treated with chemotherapy required information regarding treatment and adverse effects, and 4 studies34,36,37,39 found that patients regarded nurses as having a key role in communicating information about treatment and adverse effects. Three of the quantitative studies reported that patients receiving treatment in an outpatient clinic expressed an immense need for information from the HCP.37–39 This finding was also supported by 3 qualitative studies, as information was connected to the ability to cope with the disease, treatment, and daily life34–36 by reducing anxiety and helping patients gain control.36 Although communication and information from the HCP were experienced as essential to the patient, three of the quantitative studies found that patients had unmet information needs.38–40 Information about handling adverse effects had a problem frequency of 49% in Kleeberg et al,38 where 27% of the patients answered that they wanted more information on adverse effects. This study also found that patients who reported adverse effects (eg, pain or gastrointestinal discomforts) were less satisfied with their HCP.38

Patients experienced the nurse as a psychosocial caregiver encouraging patients to talk about issues perceived as important to them.4,34 Furthermore, patients appreciated when nurses gave the impression of having time for them34: “Even though she maybe had other things to do, she didn’t make me feel that she had anything else to do…so I felt free to talk about it.”34(p75) A qualitative study also emphasized that patients with cancer wanted to be involved in treatment and to be seen as competent partners.33 In one of the included studies, 48% of the 4615 surveyed patients reported that they were not involved in decisions regarding their treatment.38

Hope and Positivity Are a Need and a Strategy for Patients With Cancer and Are Facilitated by HCPs

Three of the 5 qualitative studies found that the attribute of maintaining hope and positivity was both a need and an important strategy for coping with the cancer disease.4,35,36 Positivity is composed of remaining with a positive attitude:4,36 “I just try to think positive that everything’s going to be alright and I try not to worry about it. Well, if you let yourself get down, then it is harder for you to keep yourself motivated and going.”36(p269) Being positive was thus turned into a coping strategy, which was associated with better outcome, whereas being negative meant working against the treatment.35 Some patients also expressed a need for the HCP to enhance hope in their interactions with them.35

Positivity was in many cases facilitated by the HCP: “The doctors said you have to be positive; if you are not positive, you won’t beat the disease. You must be positive.”36(p269) Although patients expressed a need for and had an expectation that the HCP should facilitate hope and positivity, it could conversely lead to underreporting of adverse effects or toxicities. This could lead to overlooking patient concerns and needs in the encounters with HCPs during chemotherapy.36

Outpatient Clinic Visits Frame and Influence Communication and Relationships

The studies reported both possibilities and restrictions for patients in establishing a relationship with the HCP when the encounters took place in an oncology outpatient clinic. McIlfatrick et al36 identified advantages and disadvantages of attending an oncology outpatient clinic. The study found that the outpatient location made it easier for patients to maintain a sense of normality and security associated with home, removing some of the feelings related to illness. Furthermore, attending an outpatient clinic was experienced positively because it became a part of their daily routine.4 In contrast, some patients felt isolated and alone with the disease and experienced a lack of professional support: “When I went home, I was feeling quite low and nauseous, and I was really worried about how I would get on[…]. I felt isolated and quite left alone.”36(p268) Kleeberg et al38 found that lack of communication with the HCP could hamper the patients’ ability to cope with the disease in their daily life; for example, “not receiving enough information on dealing with pain at home” had a problem frequency of 47%, and “was not told how to effectively manage side effects” had a problem frequency of 38%.

Four studies concluded the outpatient environment for administrating chemotherapy was a negative experience for some patients.35–37,40 The treatment in an outpatient clinic was compared with visiting a fast-food restaurant:36 “it is a bit factory-like. You’re getting the treatment[…]. I would like to see a bit more attention paid to your life as well as, or incorporated with, the treatment.[…] to discuss about yourself as a mother or a wife, or as a girlfriend or a retired person and your everyday life.”36(p268) Some patients experienced the treatment environment as dehumanizing, which was described by McIlfatrick et al36 as a central finding in their study. The environment in the outpatient clinic thus had an influence on patients’ experiences of their communication and relationship with the HCP.

Cameron and Waterworth4 found the patients’ experience of the atmosphere in the outpatient clinic to be influenced by how they experienced the relationship with the nurses. For instance, caring behaviors improved satisfaction with care and well-being.35 Moreover, waiting time in the outpatient clinic was experienced negatively by the patients.35–37,40 When examining other factors affecting satisfaction, patients rated the environment low (mean score, 59.4), for example, the waiting room, waiting time, and access to parking.37 However, the environment seemed to have the least influence on satisfaction with care.37

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize the literature from the perspective of the patient on the experiences of and need for relationships and communication with HCPs during chemotherapy in an outpatient setting. On the basis of 9 studies included in this review, evidence showed that the relationship and communication with HCPs were experienced as essential for patients during chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic. In particular, the relationship with the nurses was highlighted as playing an important role for coping with the disease and influenced overall satisfaction. These findings correlate well with other studies where the relationship between the patient and the HCP was the most important factor influencing patient satisfaction,17,42,43 where the experience of being acknowledged as a person with individual needs was also emphasized.44

The relational aspect of communication was stressed by the patients, as well as the importance of the HCP relating to the individual needs of patients with cancer. This finding is in line with Skea et al,45 who examined what patients with urological cancer valued in their interaction with the HCP. However, this raises the question of whether there is sufficient time to identify the individual needs of patients when encounters are brief,21 and as previously described, studies have found a risk of overlooking patients’ needs when time is limited for each patient.13,14 Nevertheless, only a few studies mentioned time as an issue. Hargie et al34 found that patients valued that nurses gave an impression of having enough time for them. Sitzia and Wood40 found that the outpatient clinic could be experienced as too busy, but lack of time was only mentioned by less than 3% of those who expressed dissatisfaction. A qualitative study exploring key issues associated with providing effective psychosocial care for hospitalized patients with cancer showed that lack of time prevented the identification of healthcare needs.14 Another qualitative study examining the nurse-patient interaction in an acute care environment revealed that some of these interactions focused on routines rather than an individualized approach to the patient.46 McIlfatrick et al21 explored nurses’ experiences of giving chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic compared with their experiences of working in an inpatient setting and found that nurses experienced a lack of ability to develop the nurse-patient relationship and insufficient time to provide psychosocial care. The study emphasized that nursing in an outpatient setting required a balance between administering chemotherapy and maintaining the centrality in the nurse-patient relationship.21 The current literature indicates that relationship-based care can decrease task-oriented care,47 and a relationship-based model can support a patient-centered environment and patient satisfaction.48

Continuity of care and meeting the same HCP were viewed as important central aspects by the patients treated in the outpatient clinic.33–35 This was in line with research evaluating satisfaction with care among patients receiving chemotherapy and radiotherapy in an oncology outpatient clinic.5 This finding might not be surprising, but perhaps, continuity of care is particularly important in an outpatient clinic where visits can be frequent and encounters with the HCP can be brief. Manthey49 has contributed to the development of the concept of primary nursing in an inpatient setting, which has been found to improve patient satisfaction in an oncology outpatient clinic.50 However, as our review revealed, the topic “continuity of care” is sparsely investigated in the oncology outpatient setting.

This review confirmed the importance of the HCP having competence in interpersonal and communication skills. The National Cancer Institute has pointed out that communication between patients and the HCP is essential for patients’ experience of quality in cancer care.17 In general, cancer treatment requires a great deal of information about treatment and adverse effects, and as identified in this review, some patients experienced unfulfilled information needs, especially related to information about the handling of adverse effects. This might be explained by the lack of time to inform patients adequately. Patient involvement in decision-making regarding treatment was important to patients with cancer.33,38 Conversely, only a few studies reported whether they investigated patients’ experiences of being involved in decision-making.33,38 Nevertheless it is notable that Kleeberg et al38 found that almost half of the 4615 surveyed patients did not experience personal involvement in decisions regarding their treatment. A systematic review concluded that most patients wanted a collaborative and active patient role but also showed that more research would be needed before clear recommendations can be made.51

Patients expressed a need for hope and positivity during cancer treatment and used these as a strategy to cope with the disease in their everyday life. The HCP was found to play a central role in enhancing hope and positivity for the patient in their interactions. Research supported that hope and positivity can lead to better coping52 and suggested that absence of hope in a patient-doctor interaction can have a negative influence on the patients’ well-being.53 Conversely, positivity was found to increase risk of the HCP overseeing patient concerns and needs and was also linked to patients downgrading some of their concerns in their encounters with the HCP. This finding was in line with McCreaddie et al54 who found that positivity can be constructed as a norm in HCP-patient encounters, which may lead to failure in identifying patients’ individual needs.4

McIlfatrick et al36 stressed the advantages of receiving chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic because it facilitated patients’ feelings of normality but also revealed that there was a risk of the patients feeling alone with their disease. Research indicated that effective psychosocial support might improve patient outcomes in relation to, for example, pain, anxiety, and depression during chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic.55,56 Benor et al57 found a significant effect on patients treated with chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic on their psychosocial symptoms when combined with home visits by nurses with a follow-up of 3 months. Nursing interventions including guidance, education, and support significantly improved symptom management in the intervention group in 15 of the 16 symptoms, for example, anxiety, pain, fluid intake, and sexuality. The largest reduction was found in psychosocial symptoms, especially on level of anxiety, body image, and sensuality.57 The results might imply that the time used to establish a relationship with the patient was an important factor in patients’ coping with the disease and treatment.

The environment in the outpatient clinic was the issue that was evaluated most negatively by patients and was even compared with a fast-food restaurant in 1 qualitative study.36 Similar findings were reported in a survey on satisfaction in an oncology outpatient clinic where patients were treated with radiotherapy or chemotherapy, whereas service and care organization, for example, environment of the buildings and access to parking,5 and physical environment, for example, comfort,58 were reported as least satisfying. A systematic review indicated that the physical healthcare environment affected the well-being of patients59; for example, sunlight and windows had positive effects. However, the review also revealed limited evidence due to a scarcity of research in this field.59

Review Strengths and Limitations

We conducted a broad literature search and applied strict systematic methods throughout this review. We also chose to include both qualitative and quantitative studies, which may have provided a more multifaceted result. Despite a comprehensive search strategy, only 9 studies were eligible for inclusion. Because of the limited number of studies, the small sample sizes, and the heterogeneity of the included studies, the results must therefore be interpreted with caution.

Methodological quality assessments were carried out using Joanna Briggs study-appropriate assessment tools, which provided a uniform and structured evaluation of the studies. The overall methodological quality of the qualitative and quantitative studies ranged between medium to high.

The review focused on the relationship between the HCP and the patient with cancer—regardless of the cancer diagnosis—but certain diagnosis groups were more represented than others. Therefore, results may not be representative of the wider population of patients with cancer. Furthermore, we initially aimed to include studies where patients were undergoing chemotherapy; however, because there were only a limited number of studies found, we also included studies where a minor part of the population received radiotherapy instead (see Tables 3 and 4). Although this review focused on the multidisciplinary HCP group, we mainly generated knowledge about the patient-nurse relationship because the HCPs included in the studies were predominantly nurses. Reasons for predominance of the nursing perspective may be explained by nurses being the ones primarily administering chemotherapy in outpatient clinics. Historically, there has also been more focus on the patient-nurse relationship in a clinical context with further development of relationship-based practice care models.12,15,16,49,60

Despite the limitations, this review provided insight regarding the significance of the relationship and communication between patients with cancer and the HCP and how it affected the patients coping with the disease and satisfaction of care in an outpatient setting. Furthermore, it helped to specify which elements of the communication are central in the patient-HCP interaction from the patients’ perspective.

Conclusions

This review revealed the importance of the patient-HCP relationship and communication as important factors in supporting and facilitating the patients’ ability to cope with cancer in everyday life. Furthermore, our review showed that the patient-HCP relationship can affect patients’ experiences of satisfaction of care in the outpatient clinic. This review also emphasized the relational aspect of communication and the importance of HCPs relating to patients’ individual needs. Patients with cancer wished to be involved in decisions regarding their treatment and to be viewed as competent partners. Finally, the limited number of studies included in our review proved the point that patients’ experiences in an oncology outpatient context have been sparsely investigated. Therefore, we suggest that more research is conducted in this area studying which type of interaction and intervention would be most effective in supporting patients in their coping with the disease while undergoing treatment in an outpatient clinic, that is, exploring whether a relationship-based care model12,60 can support patients when treated in an oncology outpatient setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the research librarian Ester Hørman from the University College Metropolitan Library for assisting with the literature search.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.McKenzie H, Hayes L, White K, et al. Chemotherapy outpatients’ unplanned presentations to hospital: a retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(7):963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandrik K. Oncology: who’s managing outpatient programs? Hospitals. 1990;64(3):32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubell AS. Inpatient versus outpatient chemotherapy—benefits, risks, and costs. Cancer Therapy Advisor. 2012. http://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/general-oncology/inpatient-versus-outpatient-chemotherapybenefits-risks-and-costs/article/247706/. Accessed July 20, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron J, Waterworth S. Patients’ experiences of ongoing palliative chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a qualitative study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(5):218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hjörleifsdóttir E, Hallberg IR, Gunnarsdóttir ED. Satisfaction with care in oncology outpatient clinics: psychometric characteristics of the Icelandic EORTC IN-PATSAT32 version. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(13–14):1784–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistics Denmark. Ambulante behandlinger 2011 [Outpatient treatments 2011, original language Danish]. http://www.dst.dk/pukora/epub/Nyt/2012/NR610.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2015.

- 7.Interior and Ministry of Health. Øget fokus på gode resultater og bedste praksis på sygehusene. udvikling i indlæggelsestid, omlægning til ambulant behandling og akutte genindlæggelser [Increased focus on good results and best practice in the hospitals. Development of hospital stay, conversion to outpatient and emergency readmissions, original language Danish]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet [Ministry of Interior and Health]; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danish Regions and the Ministry of Health. Øget fokus på gode resultater på sygehusene [Increased focus on good results at the hospitals, original language Danish]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danske Regioner Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse [Danish Regions Ministry of Health and Prevention]; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Cancer. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Accessed September 29, 2015.

- 10.Farrell C, Molassiotis A, Beaver K, Heaven C. Exploring the scope of oncology specialist nurses’ practice in the UK. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(2):160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death Department of Health. For better, for worse? 2008. http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2008report3/Downloads/SACT_report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2016.

- 12.Koloroutis M, Trout M. See Me as a Person: Creating Therapeutic Relationships with Patients and Their Families. Minneapolis, MN: Creative Health Care Management, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Plessen C, Aslaksen A. Improving the quality of palliative care for ambulatory patients with lung cancer. BMJ. 2005;330(7503):1309–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botti M, Endacott R, Watts R, Cairns J, Lewis K, Kenny A. Barriers in providing psychosocial support for patients with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(4):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zoffmann V, Prip A, Christiansen AW. Dramatic change in a young woman’s perception of her diabetes and remarkable reduction in HbA1c after an individual course of guided self-determination. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015209906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoffmann V, Kirkevold M. Realizing empowerment in difficult diabetes care: a guided self-determination intervention. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(1):103–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakker DA, Fitch MI, Gray R, Reed E, Bennett J. Patient–health care provider communication during chemotherapy treatment: the perspectives of women with breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43(1):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Given BA, Sherwood PR. Nursing-sensitive patient outcomes—a white paper. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(4):773–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rchaidia L, Dierckx de Casterlé B, De Blaeser L, Gastmans C. Cancer patients’ perceptions of the good nurse: a literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(5):528–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mcilfatrick S, Sullivan K, McKenna H. Nursing the clinic vs. nursing the patient: nurses’ experience of a day hospital chemotherapy service. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(9):1170–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manthey M. Foundations of interprofessional communication and collaboration. Creat Nurs. 2012;18(2):64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinge S. Fremtidens Plejeopgaver i Sundhedsvæsenet [Future Care Tasks in Health Care, original language Danish]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Dansk Sundhedsinstitut [Danish Health Institute]; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Mayer C, et al. Clinician-patient communication: evidence-based recommendations to guide practice in cancer. Curr Oncol. 2009;16(6):42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry LL, Mate KS. Essentials for improving service quality in cancer care. Healthcare. 2016;4(4):312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsianakas V, Maben J, Wiseman T, et al. Using patients’ experiences to identify priorities for quality improvement in breast cancer care: patient narratives, surveys or both? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shirk JD, Tan HJ, Hu JC, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. Patient experience and quality of urologic cancer surgery in US hospitals. Cancer. 2016;122(16):2571–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in America 2016. http://www.asco.org/research-progress/reports-studies/cancer-care-america-2016. Accessed December 7, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Berry LL, Beckham D, Dettman A, Mead R. Toward a strategy of patient-centered access to primary care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(10):1406–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 Edition. Adelaide, SA, Australia: The University of Adelaide; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331(7524):1064–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ekwall E, Ternestedt BM, Sorbe B, Graneheim UH. Patients’ perceptions of communication with the health care team during chemotherapy for the first recurrence of ovarian cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(1):53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hargie O, Brataas H, Thorsnes S. Cancer patients’ sensemaking of conversations with cancer nurses in outpatient clinics. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2009;26(3):70–78. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hjörleifsdóttir E, Hallberg IR, Gunnarsdóttir E, Bolmsjö I. Living with cancer and perception of care: Icelandic oncology outpatients, a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(5):515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIlfatrick S, Sullivan K, McKenna H, Parahoo K. Patients’ experiences of having chemotherapy in a day hospital setting. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(3):264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arraras JI, Illarramendi JJ, Viudez A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction with care in a Spanish oncology day hospital and its relationship with quality of life. Psychooncology. 2013;22(11):2454–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleeberg UR, Feyer P, Gunther W, Behrens M. Patient satisfaction in outpatient cancer care: a prospective survey using the PASQOC questionnaire. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(8):947–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto AC, Ferreira-Santos F, Lago LD, et al. Information perception, wishes, and satisfaction in ambulatory cancer patients under active treatment: patient-reported outcomes with QLQ-INFO25. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sitzia J, Wood N. Study of patient satisfaction with chemotherapy nursing care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 1998;2(3):142–155. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McWilliam CL, Brown JB, Stewart M. Breast cancer patients’ experiences of patient-doctor communication: a working relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(2-3):191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salander P, Henriksson R. Severely diseased lung cancer patients narrate the importance of being included in a helping relationship. Lung Cancer. 2005;50(2):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skea ZC, Maclennan SJ, Entwistle VA, N’dow J. Communicating good care: a qualitative study of what people with urological cancer value in interactions with health care providers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(1):35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bolster D, Manias E. Person-centred interactions between nurses and patients during medication activities in an acute hospital setting: qualitative observation and interview study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(2):154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodney PA. The Design and Implementation of a Relationship-Based Care Delivery Model on a Medical-Surgical Unit [dissertation]. Minneapolis, MN: Walden University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cropley S. The relationship-based care model: evaluation of the impact on patient satisfaction, length of stay, and readmission rates. JONA. 2012;42(6):333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manthey M. The Practice of Primary Nursing. 2nd ed Minneapolis, MN: Creative Health Care Management, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cortese M. Oncology nursing news. http://nursing.onclive.com/publications/oncology-nurse/2014/june-2014/implementation-of-modified-primary-nursing-in-an-ambulatory-cancer-center#sthash.z1bkMkxQ.dpuf. Accessed December 13, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision making of patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):299–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piil K, Juhler M, Jakobsen J, Jarden M. Daily life experiences of patients with a high-grade glioma and their caregivers: a longitudinal exploration of rehabilitation and supportive care needs. J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;47(5):271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eliott J, Olver I. The discursive properties of “hope”: a qualitative analysis of cancer patients’ speech. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(2):173–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCreaddie M, Payne S, Froggatt K. Ensnared by positivity: a constructivist perspective on “being positive” in cancer care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(4):283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devine EC, Westlake SK. The effects of psychoeducational care provided to adults with cancer: meta-analysis of 116 studies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1369–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer TJ, Mark MM. Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychol. 1995;14(2):101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benor DE, Delbar V, Krulik T. Measuring impact of nursing intervention on cancer patients’ ability to control symptoms. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21(5):320–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen TVF, Anota A, Brédart A, Monnier A, Bosset J, Mercier M. A longitudinal analysis of patient satisfaction with care and quality of life in ambulatory oncology based on the OUT-PATSAT35 questionnaire. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dijkstra K, Pieterse M, Pruyn A. Physical environmental stimuli that turn healthcare facilities into healing environments through psychologically mediated effects: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(2):166–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koloroutis M. Relationship-Based Care. A Model for Transforming Practice. Minneapolis, MN: Creative Health Care Management, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]