ABSTRACT

Objective:

The aim of this systematic review was to identify and synthesize the best available evidence on first time fathers’ experiences and needs in relation to their mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood.

Introduction:

Men's mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood is an important public health issue that is currently under-researched from a qualitative perspective and poorly understood.

Inclusion criteria:

Resident first time fathers (biological and non-biological) of healthy babies born with no identified terminal or long-term conditions were included. The phenomena of interest were their experiences and needs in relation to mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood, from commencement of pregnancy until one year after birth. Studies based on qualitative data, including, but not limited to, designs within phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography and action research were included.

Methods:

A three-step search strategy was used. The search strategy explored published and unpublished qualitative studies from 1960 to September 2017. All included studies were assessed by two independent reviewers and any disagreements were resolved by consensus or with a third reviewer. The recommended Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) approach to critical appraisal, study selection, data extraction and data synthesis was used.

Results:

Twenty-two studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review, which were then assessed to be of moderate to high quality (scores 5–10) based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research. The studies were published between 1990 and 2017, and all used qualitative methodologies to accomplish the overall aim of investigating the experiences of expectant or new fathers. Nine studies were from the UK, three from Sweden, three from Australia, two from Canada, two from the USA, one from Japan, one from Taiwan and one from Singapore. The total number of first time fathers included in the studies was 351. One hundred and forty-four findings were extracted from the included studies. Of these, 142 supported findings were aggregated into 23 categories and seven synthesized findings: 1) New fatherhood identity, 2) Competing challenges of new fatherhood, 3) Negative feelings and fears, 4) Stress and coping, 5) Lack of support, 6) What new fathers want, and 7) Positive aspects of fatherhood.

Conclusions:

Based on the synthesized findings, three main factors that affect first time fathers’ mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood were identified: the formation of the fatherhood identity, competing challenges of the new fatherhood role and negative feelings and fears relating to it. The role restrictions and changes in lifestyle often resulted in feelings of stress, for which fathers used denial or escape activities, such as smoking, working longer hours or listening to music, as coping techniques. Fathers wanted more guidance and support around the preparation for fatherhood, and partner relationship changes. Barriers to accessing support included lack of tailored information resources and acknowledgment from health professionals. Better preparation for fatherhood, and support for couple relationships during the transition to parenthood could facilitate better experiences for new fathers, and contribute to better adjustments and mental wellbeing in new fathers.

Keywords: First time father, expectant father, mental health, wellbeing, perinatal period

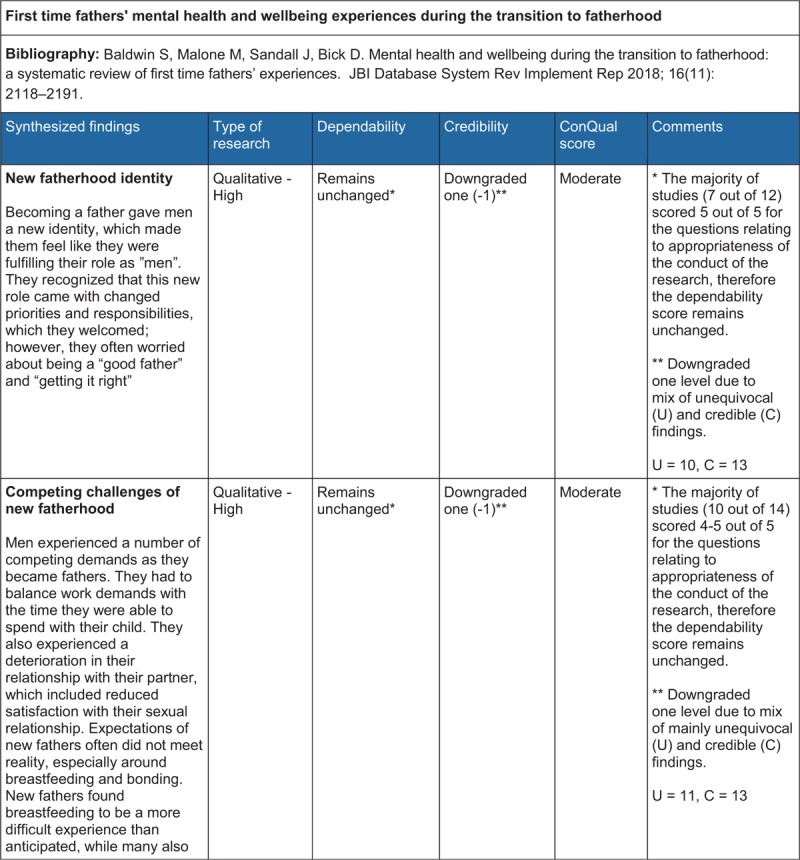

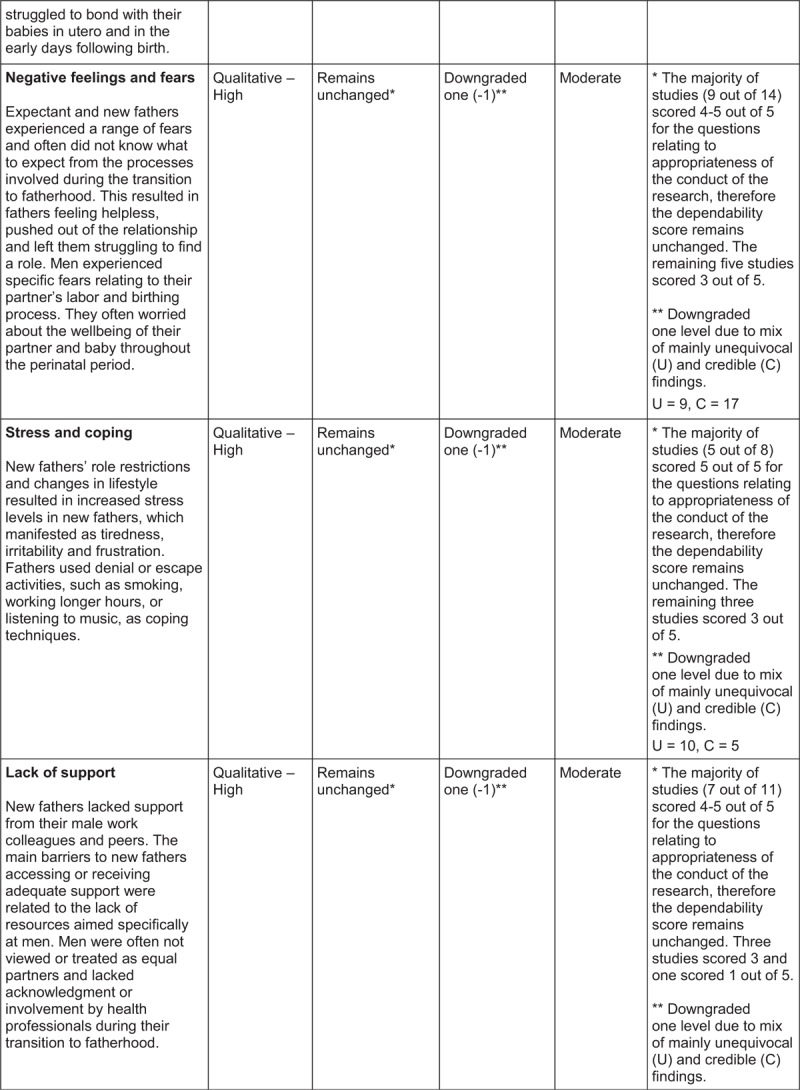

ConQual Summary of Findings1

Introduction

Fathers’ mental health and wellbeing

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as “a state of wellbeing in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.2(p.XIX) The Royal Society for Public Health in the UK has recommended that it is important to actively promote positive mental wellbeing rather than just focusing on preventing and treating mental illness.3 Men's mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood is an important public health issue that continues to be under-researched from a qualitative perspective and poorly understood.4 Poor mental health in fathers can impact negatively on their children, their partner and wider society.

Ramchandani et al.5 in a prospective cohort study, which controlled for mothers’ depression and fathers’ education levels, found that severe postnatal depression in fathers was associated with emotional and behavioral problems in their children at three years of age, particularly in boys. Moreover, children with two depressed parents were at higher risk of poor development outcomes.6 In a later study, Ramchandani et al.7 also reported an increased risk for psychiatric, behavioral and conduct disorders in children aged seven years if their fathers had been depressed during the postnatal period. Several studies have suggested a link between poor cognitive, behavioral, social and emotional development in children, and a negative father-child relationship.8-12 Poor mental health in fathers can also have an impact on the mother and the couple's relationship.13 A study of first time parents’ transition to parenthood highlighted the importance of focusing interventions on strengthening couple relationships and parents’ feelings of unworthiness.14

Anxiety and depression are the two most common mental health problems experienced by fathers in the perinatal period.4,15-24 A recent systematic review of 43 papers reported the prevalence rates of anxiety disorder in men to range between 4.1%–16% during their partners’ pregnancy and 2.4%–18% during the postnatal period.15 In another systematic review of 20 studies, the prevalence rates of antenatal and postnatal depression in fathers ranged from 1.2%–25.5%.16 With the exception of one study, which assessed depression through symptoms in a qualitative interview, the remaining studies in this review used standardized self-report instruments with established reliability and validity.16 A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported depression in 10.4% of fathers between the first trimester of their partner's pregnancy and one year postpartum, with the peak time being between three and six months after the birth, similar to findings for postnatal women.4 Symptoms of anxiety and stress have also been reported alongside depression among men during and after their partner's pregnancy.17-23 A literature review of 32 studies published between 1989–2008 on men's psychological transition to fatherhood, found pregnancy to be the most demanding period for the fathers’ psychological reorganisation of self, and labour and birth to be the most emotional moments involving highly mixed feelings, ranging from helplessness and anxiety to pleasure and pride.24 The postnatal period (defined in the review as up to one year following birth), however, was the most challenging time, due to fathers having to balance the various demands placed on them including personal and work related needs, their new role as a parent, emotional and relational needs of the family, and societal and economic pressures.24 A key element highlighted in the review was the importance of the quality of each man's relationship with his partner across the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods. The study included resident fathers, but not non-biological fathers (such as adoptive fathers), stepfathers or fathers in same sex relationships. Therefore, the experiences of non-biological fathers during their transition to fatherhood remains unknown.

A more recent systematic review of 18 studies which examined stress in fathers in the perinatal period indicated that fathers’ stress levels increased from the antenatal period to the time of birth, with subsequent decrease in stress levels from birth to the later postnatal period,23 in contrast to the above findings.24 The main factors that contributed to stress in fathers in the perinatal period included negative feelings about the pregnancy, role restrictions related to becoming a father, fear of childbirth and feelings of incompetence about infant care.23

Current interventions and gaps in evidence

A Cochrane systematic review of group-based parenting programs for improving parental psychosocial health, found that only four of the 48 included studies reported separate outcome data from fathers.25 While these showed a statistically significant short-term improvement in paternal stress following interventions that included cognitive and behavioral strategies, individual study results were inconclusive for any effect on depressive symptoms, confidence or partner satisfaction. The review authors concluded that this was “a serious omission given that fathers now play a significant role in childcare and research suggests that their psychosocial functioning is key to the wellbeing of children”.25(p.21)

A review of interventions for prevention or treatment of depression in fathers identified four studies, all focusing on treatment rather than prevention, and reported inconclusive findings due to wide study heterogeneity.26 The reviewers recommended the need for randomized controlled trials of effective mental health interventions for men in the postnatal period, particularly preventative interventions. Although this study was described as a systematic review, there was no evidence of the included studies being critically appraised, which raises concerns about the quality of the findings. Another systematic review of intervention programs to prevent or treat paternal mental illness in the perinatal period included 11 studies: five of which described psychosocial programs (emphasising skills, knowledge, emotional wellbeing, and social wellbeing related to parenting), three focused on the effects of massage techniques (partner massage and infant massage), and three which used couple-based sessions (focused on the couple relationship and co-parenting).27 Six of the eight randomized controlled trials included did not provide adequate information on randomisation processes and risk of bias could not be ruled out. The review authors reported significant intervention effects for a range of fathers’ mental health outcomes (including stress, depression, anxiety, anger levels and self-esteem) for two trials of psychosocial approaches,28,29 and three of massage techniques.30-32 There were no significant changes reported in paternal mental health following couple-based interventions.

Health professionals’ failure to engage with fathers during or around the time of birth could be a reason for the lack of evidence on first time fathers’ mental health and wellbeing.33 Fathers may feel marginalised and unacknowledged by health professionals during the perinatal period, and report a lack of appropriate information on pregnancy, birth, childcare, and balancing work and family responsibilities.34-36 Research into the role of health visitors (public health nurses in the UK) found that they do not involve fathers in routine contacts37 and were perceived by some fathers as a service provided “by women, for women”.38 A Department of Health for England funded literature review on service users’ views suggested that some fathers welcomed the opportunity to express their feelings and emotions about fatherhood when asked by a healthcare professional,39 but did not always have the opportunity to do this spontaneously.40

A systematic review of evidence on parenting interventions which included men as parents or co-parents showed that insufficient attention was paid to reporting fathers’ participation and fathers’ impacts on child or family outcomes.41 A rapid review to update evidence for the Healthy Child Programme in England included systematic review level evidence published from 2008 to 2014.42 It recognized the need to support fathers during the transition to parenthood, the lack of interventions designed specifically to support fathers and the need for further evaluations of parenting interventions that actively engaged fathers. The review made no specific reference to interventions aimed at improving fathers’ mental health and wellbeing during the perinatal period. This highlights the crucial importance of assessing men's mental health in the perinatal period,43 and identifying the best approaches to supporting fathers.44

While a number of studies relating to fathers’ mental health have been discussed above, the majority of the studies were quantitative in nature, focusing on incidence and symptoms. Few studies to date have explored first time fathers’ experiences and their perceived needs, or distinguished between biological and non-biological fathers, or if fathers were resident or non-resident in the family home. Better understanding of the experiences of first time fathers during their transition to fatherhood and identifying the level and content of information and support which could help their mental health and wellbeing, could inform the healthcare professional-led interventions acceptable to meet their needs. Barriers and facilitators to first time fathers accessing timely and appropriate support for their mental health and wellbeing needs could also be identified. This systematic review aimed to create a deeper knowledge of first time fathers’ experiences, needs and help seeking behaviors relating to mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood and how fathers could be better supported during this time.

In this review, first time fathers refers to men becoming either a biological or non-biological parent for the first time, and resident fathers refers to those who resided with their expectant partner, or their partner and child during their transition to fatherhood. The transition to fatherhood was defined as the period from conception to one year after birth. Mental health problems included any psychological difficulty or distress including depression, anxiety and stress. These may have been diagnosed by a health professional or self-reported by fathers. Mental wellbeing included positive mental health, covering both the hedonic (feeling good) and eudemonic components (functioning well) of psychological wellbeing.

Initial searches of the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PROSPERO and DARE databases were conducted and although a small number of systematic reviews relating to this topic were identified and cited above, no qualitative systematic reviews were identified which answered the questions of this review.

The aim of this qualitative review was therefore to identify first time fathers’ experiences and needs in relation to their mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood.

Review question/objective

The objective of this systematic review was to identify and synthesize the best available evidence on first time fathers’ experiences and needs in relation to their mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood.

Specifically, it sought to evaluate:

How mental health and wellbeing are experienced by first time fathers.

The perceived needs of first time fathers around mental health.

The ways in which mental health problems are experienced, manifested, recognized and acted upon by first time fathers.

The contexts and strategies that are perceived by first time fathers to support mental wellbeing.

The perceived barriers and facilitators to first time fathers accessing support for their mental health and wellbeing.

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Study participants included first time fathers of healthy babies born at full term with no identified terminal or long-term conditions. As this review focused on the mental health and wellbeing of fathers in general and not of those with specific additional needs, studies were excluded if they considered:

Non-resident/absent fathers (those not residing with the partner/child during the period between conception to one year after birth).

Fathers experiencing bereavement following neonatal death, stillbirth, pregnancy loss or sudden infant death.

Fathers whose infants were born prematurely (≤37 weeks gestation).

Fathers of a child with terminal/long term conditions.

Phenomena of interest

The phenomenon of interest for this review was first time fathers’ experiences and needs during their transition to fatherhood in relation to their mental health and wellbeing.

Context

This review considered studies undertaken in high income countries as defined by the World Bank45 (for example, countries which are members of the European Economic Community, the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand). The majority of these countries have similar healthcare systems (with a mix of public and privately funded universal service provision), and social and political systems, meaning that review findings are likely to be more transferable.

Types of studies

The review considered studies that focused on qualitative data including, but not limited to, designs such as phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography and action research. The review also considered qualitative data reported within quantitative surveys for inclusion, where open questions relating to the phenomena of interest had been asked.

Methods

The objectives, inclusion criteria and methods of analysis were specified in advance. The review was conducted according to the protocol, published in the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports (DOI: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003031).46 The protocol was also registered with PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2016:CRD42016052685).

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to identify published and unpublished studies. A three-step search strategy was utilized. An initial limited search of MEDLINE (using Ovid) and CINAHL was undertaken followed by analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and index terms used to describe the article. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was then undertaken across all included databases. Thirdly, the reference list of all identified reports and articles were searched for additional studies.

Studies published in English were considered for inclusion as resources for translation were not available to the reviewers. Searches were conducted between January and September 2017 and computerized searches for studies published from 1960 to the present were considered for inclusion, to reflect the shift in fathers’ roles following the feminist movement.

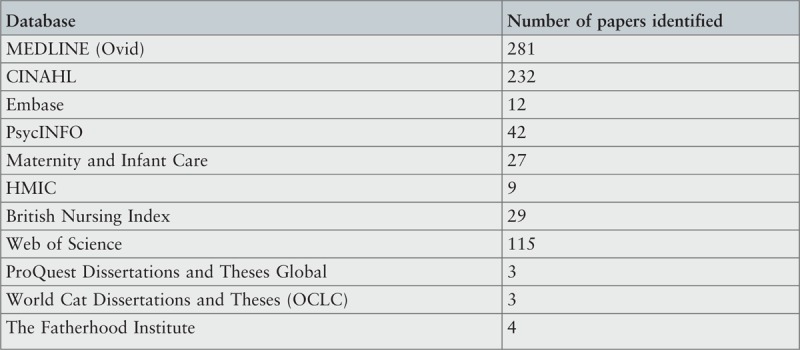

The databases searched included: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, Maternity and Infant Care, HMIC, British Nursing Index and Web of Science.

Searches were also carried out of the website of The Fatherhood Institute, the UK's leading charitable organisation for fathers and fatherhood. The Institute collates and publishes international research on fathers and impact of their role on children and mothers.

The search for unpublished studies such as theses and dissertations included: ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global and WorldCat Dissertations and Theses (OCLC).

A full list of all databases searched and papers identified are presented in Appendix I, and an example of one of the searches undertaken (MEDLINE) is presented in Appendix ll.

Study selection

The initial database searches and citation tracking was performed by the first author (SB). After pooling the retrieved titles, all duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (SB, DB) screened the titles independently and the final list of potential titles was created by compiling the lists of the two reviewers. The same process was repeated during the abstract screening where each reviewer read the abstracts independently and the selected abstracts were merged. Authors of the primary studies were contacted when the full text articles were not accessible. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through comprehensive discussions to reach an agreement.

There were a number of studies where it was unclear if participants were first time or subsequent fathers, or residing with their partners or not. For such papers, where the authors’ contact details were available, they were contacted for further clarification. Papers were excluded if it was not possible to obtain further clarification. Quantitative studies, review articles, meta-analyses or meta-syntheses, editorials, commentaries, letters, conference abstracts, studies with no available full-text and non-English studies were also excluded.

Assessment of methodological quality

Qualitative papers selected for retrieval were assessed by two independent reviewers (SB, DB) for methodological validity prior to inclusion in the review using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research as appended in the original protocol for this review.46 This enabled the reviewers to engage with and better understand the methodological strengths and limitations of the selected primary studies.

Data extraction

Qualitative data were extracted from the included papers using the standardized JBI data extraction tool.46 The data extracted included specific details on methodology, methods, phenomena of interest and findings relevant to the review question and specific objectives. During the data extraction process, a level of “credibility” was allocated to each finding based on the degree of support offered by each illustration associated with it. The first reviewer assigned levels of credibility to each of the findings using the three levels as described by the standardized JBI qualitative data extraction tool:

-

i)

Unequivocal (U): findings accompanied by an illustration beyond reasonable doubt and therefore not open to challenge.

-

ii)

Credible (C): findings accompanied by an illustration lacking clear association with it and therefore open to challenge.

-

iii)

Unsupported (US): findings are not supported by the data.

These were then discussed amongst the three reviewers (SB, DB, MM) resulting in general consensus with allocation of these levels.

Data synthesis

Qualitative research findings were pooled using Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). Findings were identified through repeated reading of text, and selection of themes from the results section. Most of the findings were based on the themes identified by the study authors in their qualitative analysis. The three-step process of data synthesis involved:

-

i)

Extraction of all findings from all included papers with an accompanying illustration and establishing a level of credibility for each finding.

-

ii)

Categorization of findings based on the similarity in meaning and concepts.

-

iii)

Development of a comprehensive set of aggregated findings (of at least two categories) that could be used as a basis for evidence-based practice.

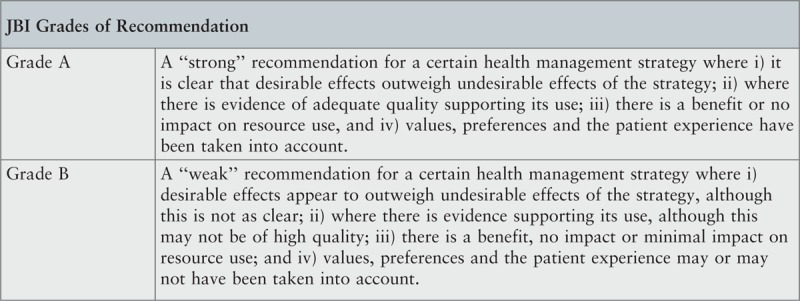

The categories, synthesized findings and accompanying descriptions were created using words and terminologies used by participants in the illustrations. These were discussed by the review team and revised until consensus was reached, prior to finalization. The reviewers also evaluated the synthesized findings with the ConQual1 approach to establish a level of confidence in each synthesized finding (Summary of Findings).

Results

Study inclusion

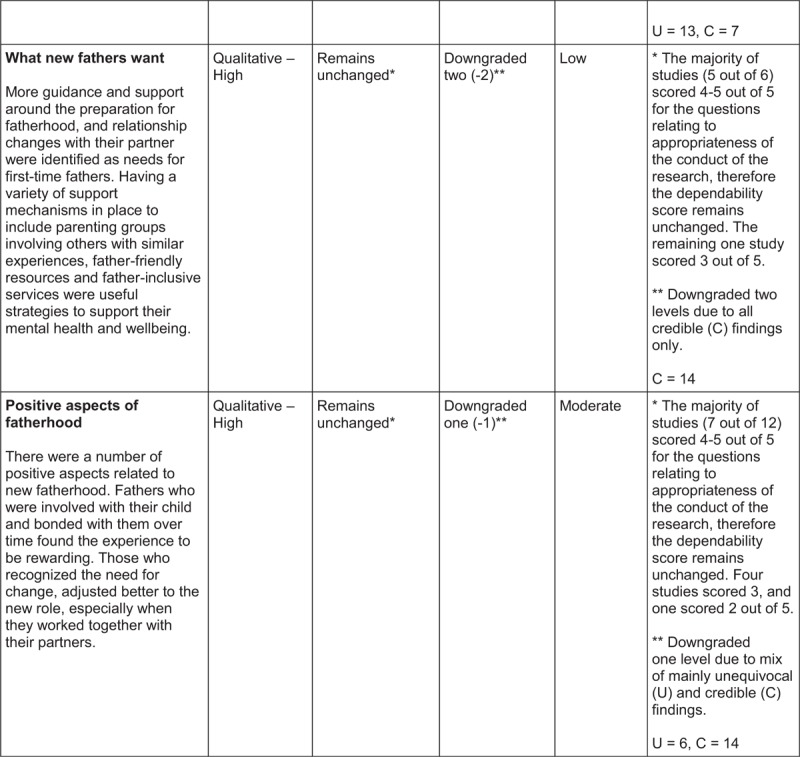

The literature search initially returned 285 records through database searching and nine through hand-searching reference lists of these papers, resulting in 294 potentially relevant records. On further examination of the study titles and abstracts, 195 of these records were excluded for various reasons, including duplication, quantitative study designs, opinion papers, those not focusing on the phenomena of interest or not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 99 articles were retrieved for a full review, following which, 77 were excluded based on the agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria (two were not original research, 37 had ineligible population, 21 had ineligible phenomena of interest and 17 had ineligible study design), leaving 22 articles to be examined for methodological quality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search and study selection process

Methodological quality

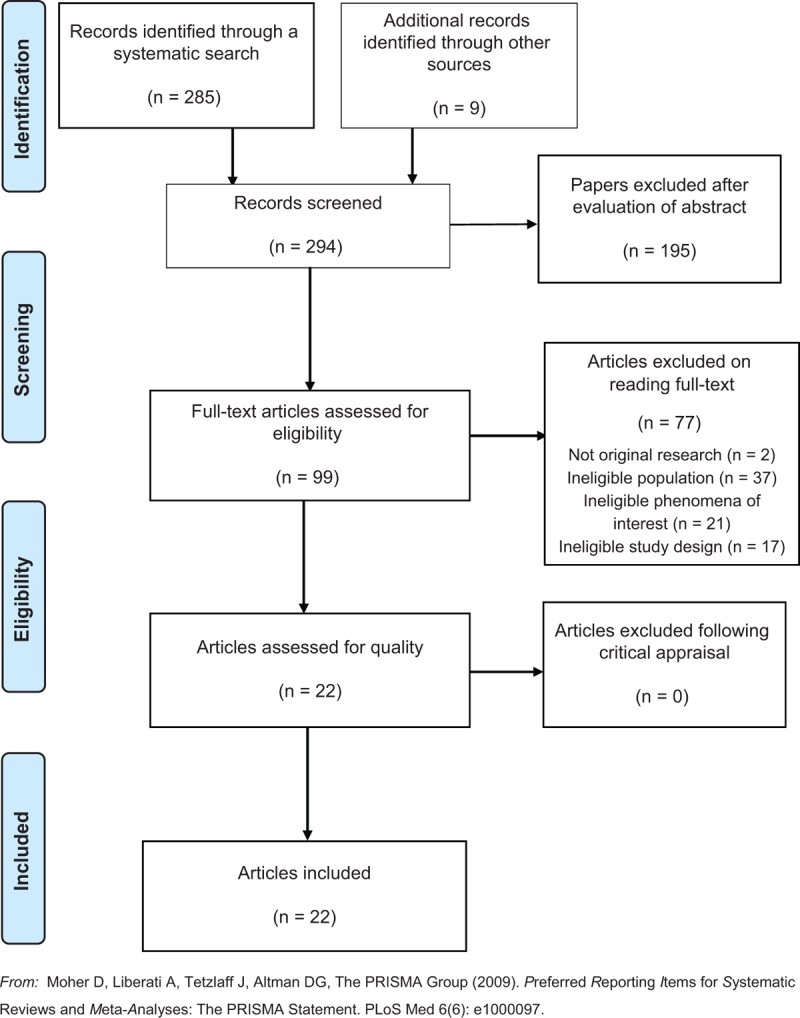

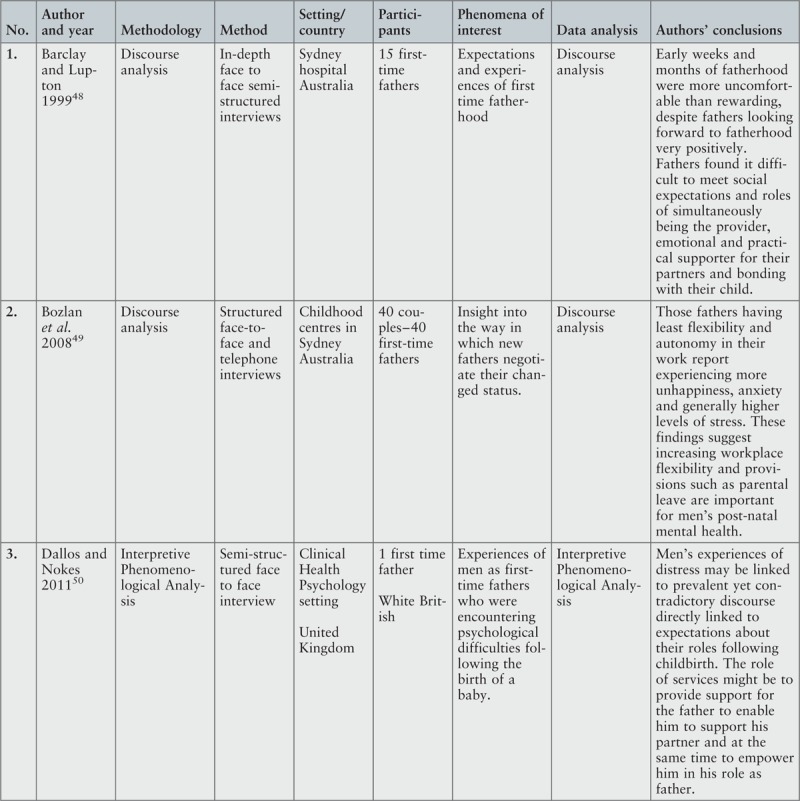

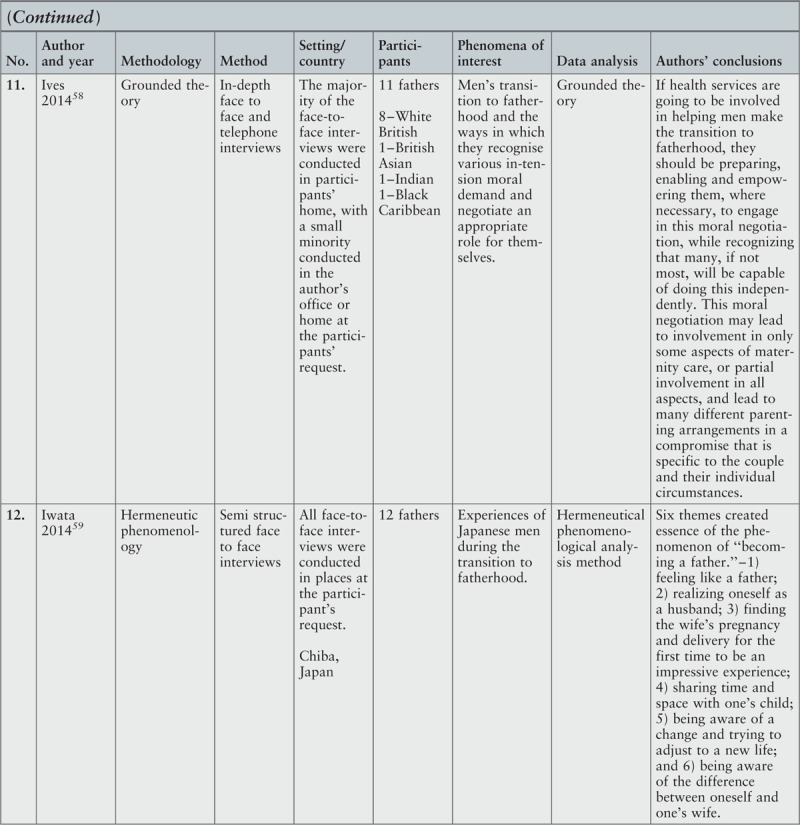

The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research46 provided a framework for scoring the quality of qualitative studies by addressing different aspects of the research such as ethical considerations, potential bias, integrity of the methodology, and congruity between methods, results and conclusion. Nine of the 22 studies scored 10 out of 10 on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research.50,53,54,57,61,63,64,65,68 Of the remaining studies, three scored nine,49,59,60 five scored eight,47,51,52,58,66 three scored seven,55,56,67 one scored six48 and one scored five.62 In all included studies there was congruity between the research methodology, research questions/objectives, and the representation and analysis of data. The descriptions of the methodology and methods of the 22 studies were clearly reported which supports the transferability of the findings. The analyses used for the studies were adequately described and were in line with the aims of the studies. On reviewing the papers, however, it was apparent that many of the studies did not include statements locating the researchers’ cultural or theoretical position, or the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa, making it difficult to determine the level of dependability of the study findings. This omission may have been due to the word restrictions set by journals. This was further discussed between the two reviewers (SB, DB) and for most of the papers any disagreements that arose between the two reviewers (SB, DB) were resolved through discussion. For two papers it was necessary to involve a third reviewer (MM). Following the third reviewer's (MM) appraisal of the papers and further discussion, consensus was reached among all three reviewers, which resulted in the final included papers presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Critical appraisal of included studies

| Included studies | Q1 | Q2* | Q3* | Q4* | Q5 | Q6* | Q7* | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

| Barclay and Lupton47 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Bozlan et al.48 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | U |

| Dallos and Nokes49 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Darwin et al.50 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Deave and Johnson51 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| De Montigny and Lacharité52 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Dolan and Coe53 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Finnbogadottir et al.54 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Henderson and Brouse55 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| Henwood and Procter56 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Ives57 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Iwata58 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Jordan59 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Kao and Long60 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Kowlessar et al.61 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Machin62 | U | Y | U | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Olsson et al.63 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Palsson et al.64 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Poh et al.65 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Rowe et al.66 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | U | Y |

| Shirani and Henwood67 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | N | Y |

| Taniguchi et al.68 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

*ConQual dependability questions:

N, No; U, Unclear; Y, Yes.

Criteria for the critical appraisal of qualitative evidence:

Q1 = Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?

Q2 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?

Q3 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?

Q4 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?

Q5 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?

Q6 = Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?

Q7 = Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed?

Q8 = Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented?

Q9 = Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?

Q10 = Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

The 22 included papers were assessed to be of moderate to high quality as the score ranged between 5 and 10 on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research and therefore none were excluded for reasons of quality. Table 1 includes assessments of methodological quality and corresponding results.

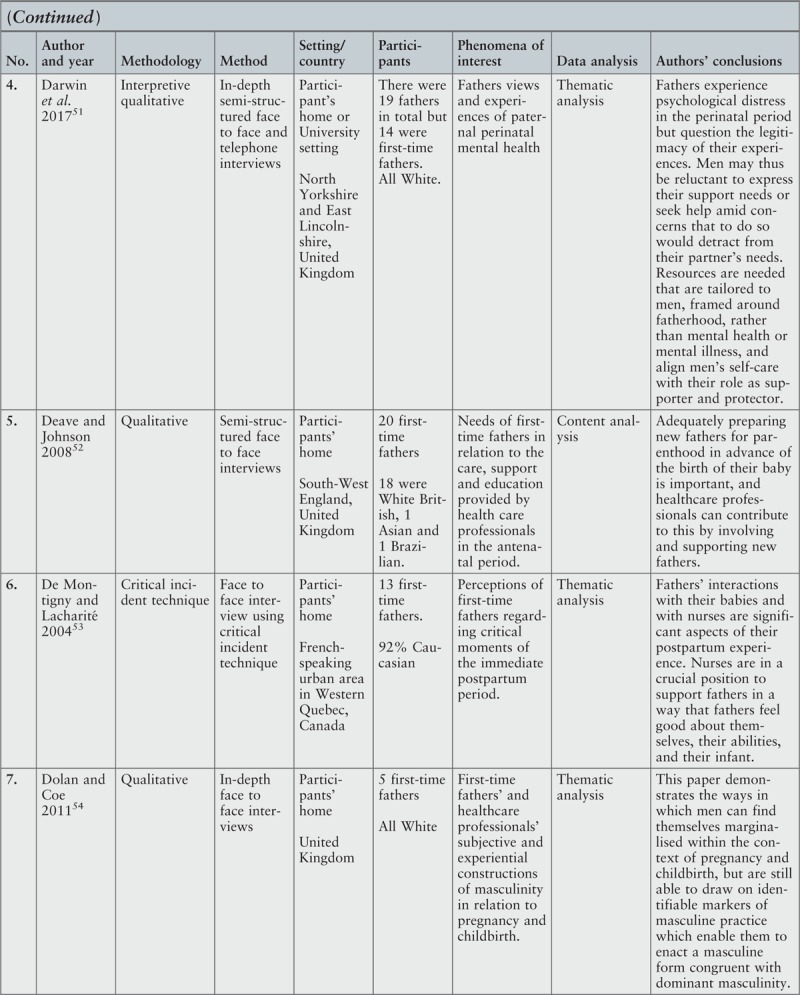

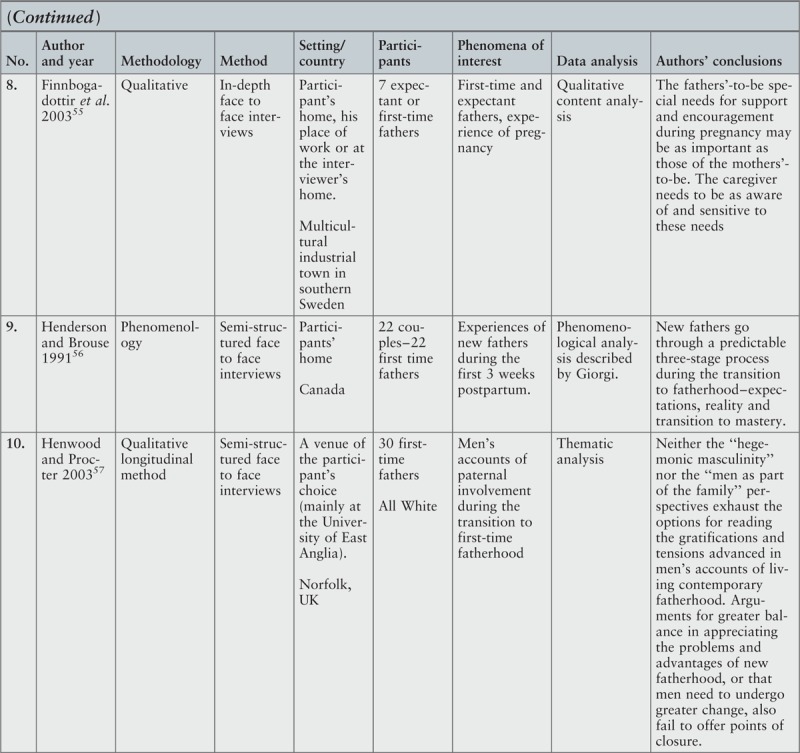

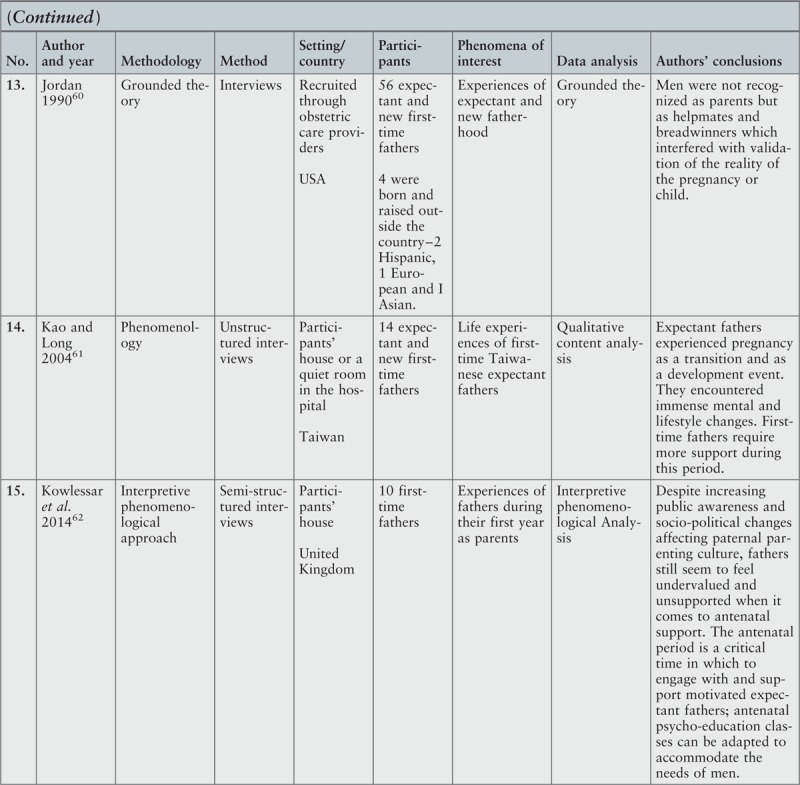

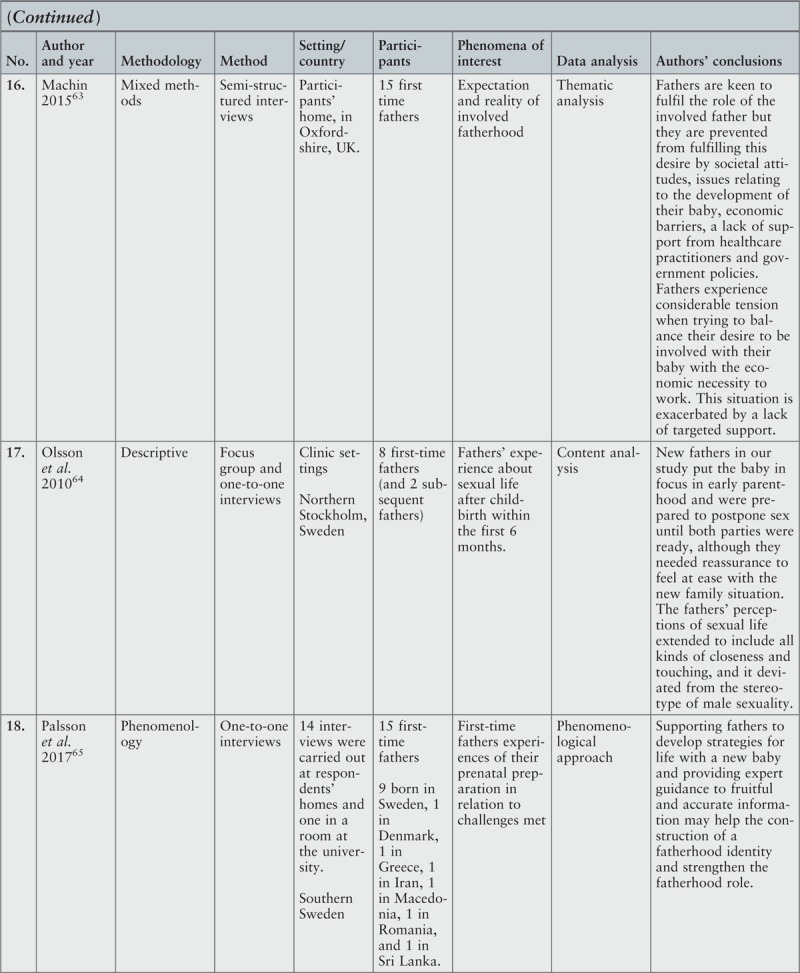

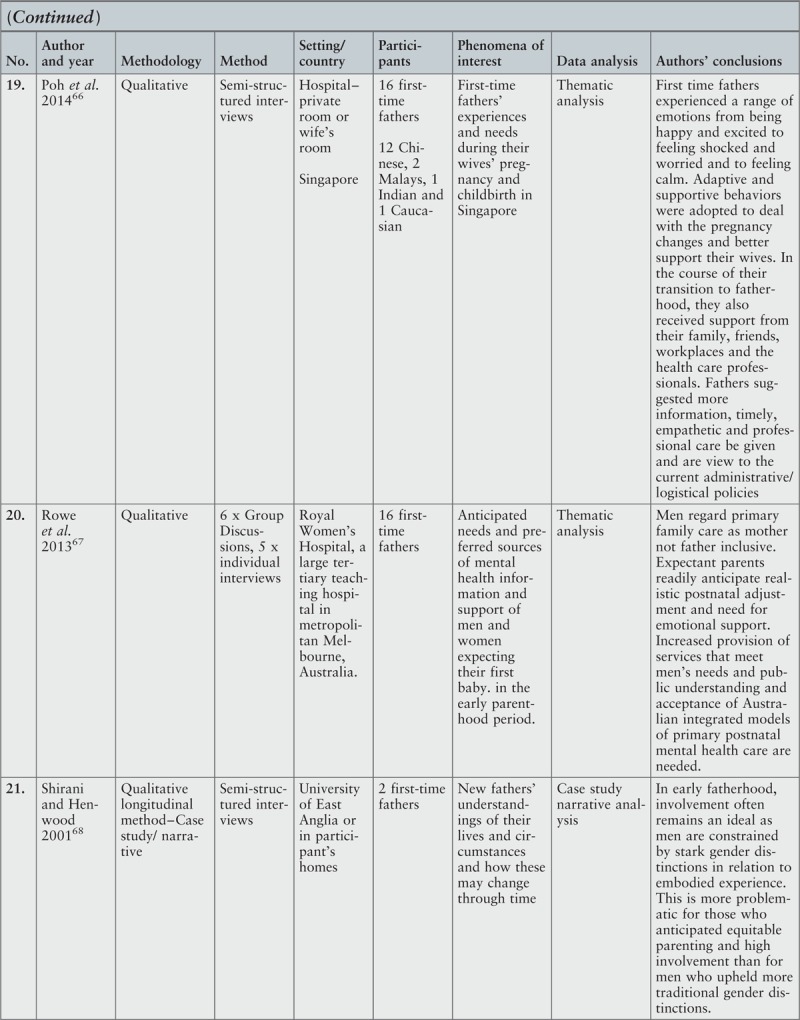

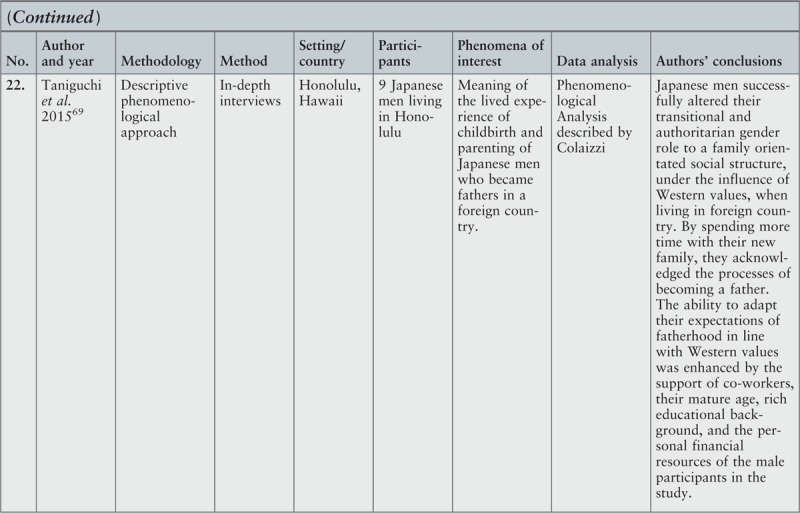

Characteristics of included studies

The 22 included studies were published between 1990 and 2017, and all used qualitative methodologies to investigate the experiences of expectant or new fathers. Nine studies were from the UK, three from Sweden, three from Australia, two from Canada, two from the USA, one from Japan, one from Taiwan and one from Singapore. The total number of first time fathers included in the studies was 351.

For the 22 included qualitative papers:

Methods included: phenomenology (seven), unspecified qualitative (eight), grounded theory (two), discourse analysis (two), narrative (two) and critical incident technique (one).

Twenty studies focused on first time fathers only, investigating their expectations, experiences, views, needs or involvement as new fathers. Of these, two studies included couples and two included both expectant and new fathers.

The remaining two studies included both first time and subsequent fathers, one specifically investigating experiences of paternal perinatal mental health and the other sexual relationship following birth from the perspective of male partners.

The data collection methods used were primarily semi-structured or in-depth interviews, carried out face-to-face or by telephone. In two studies, group discussions/focus groups were used in addition to the interviews.

Data analysis methods were consistent with the qualitative methodology used in each individual study.

Full characteristics of the 22 included studies are presented in Appendix III.

Review findings

Each included paper was read by the two reviewers (SB, DB) and findings extracted. Each finding was accompanied by illustrations from the study to place them in context and assigned a level of credibility. For example, finding 3 was Changing relationship with partner. This was supported by an illustration from the study as follows:

“The first week was great, then after that things started to get worse. I never thought that Jenny and I would have fought so much”.47(p.1018)

This illustration supported the authors’ finding, and as risk of misinterpretation was minimal, it was considered to be “unequivocal”.

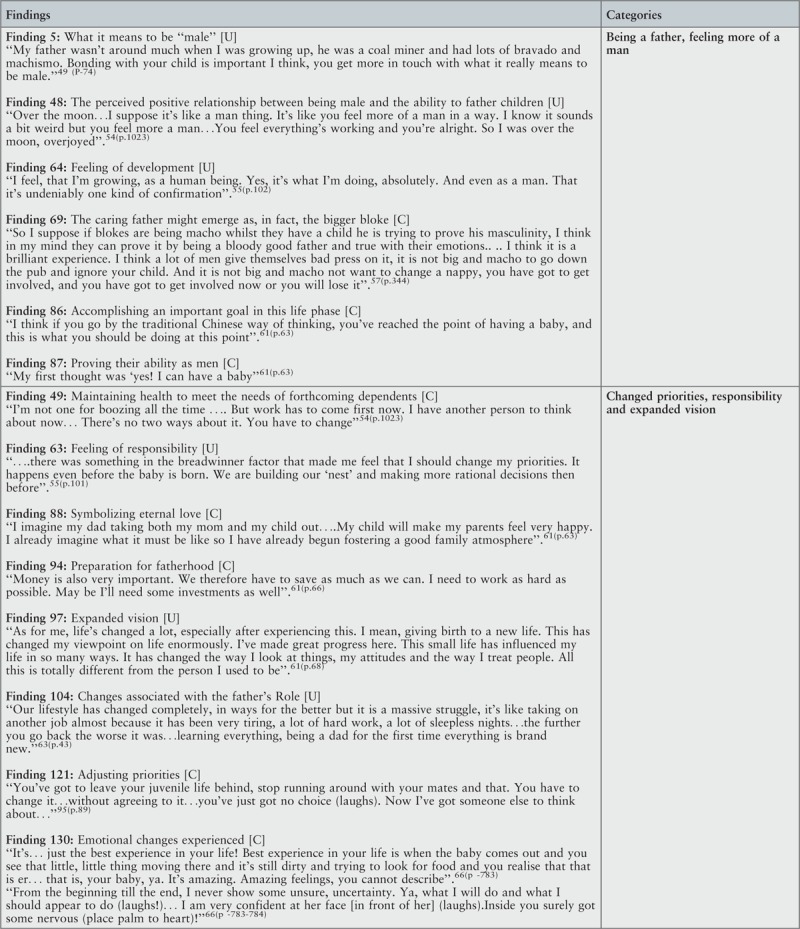

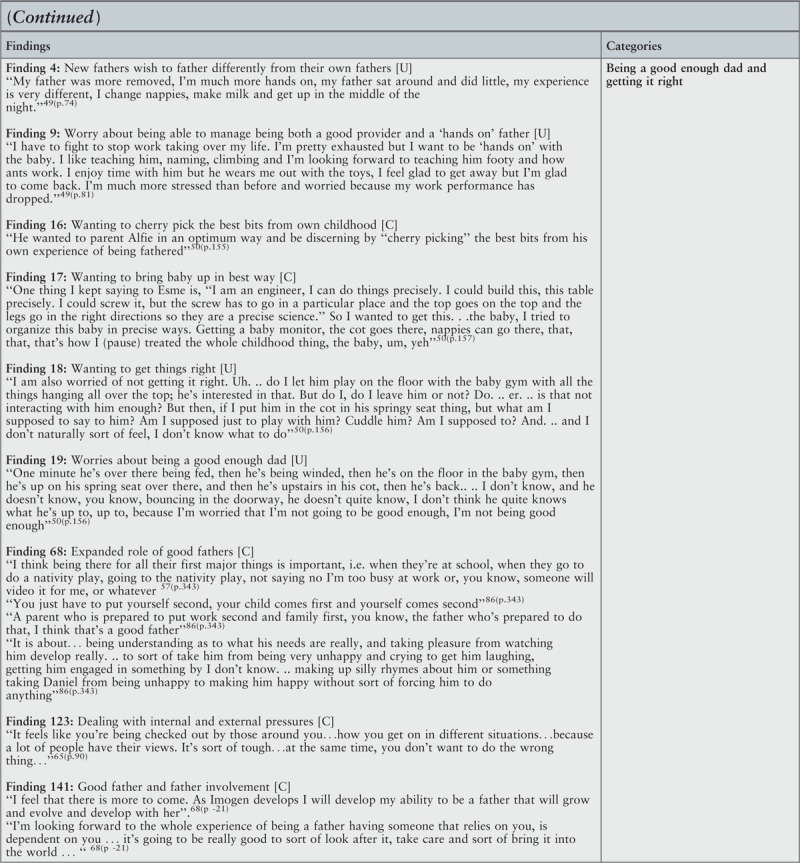

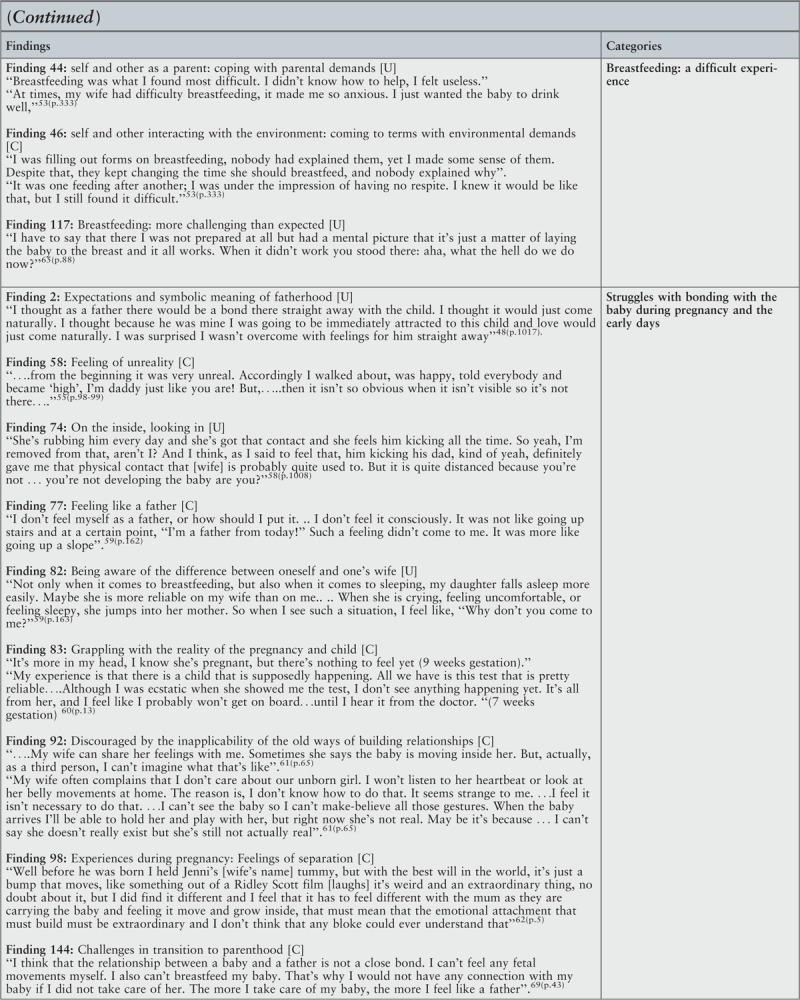

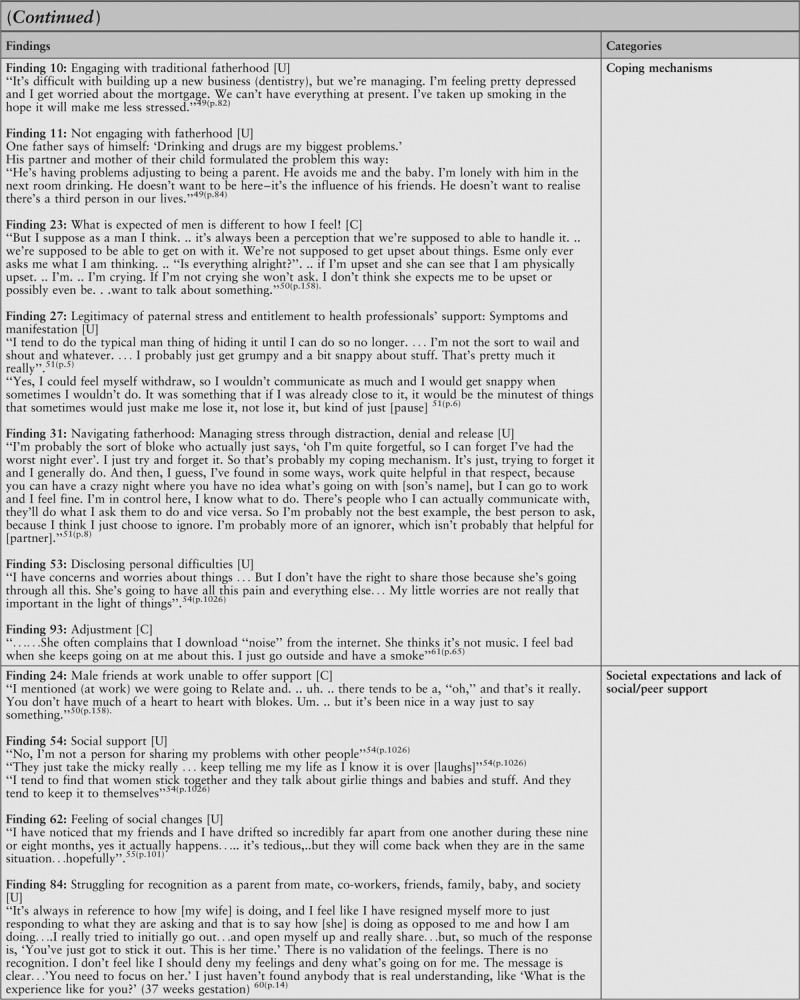

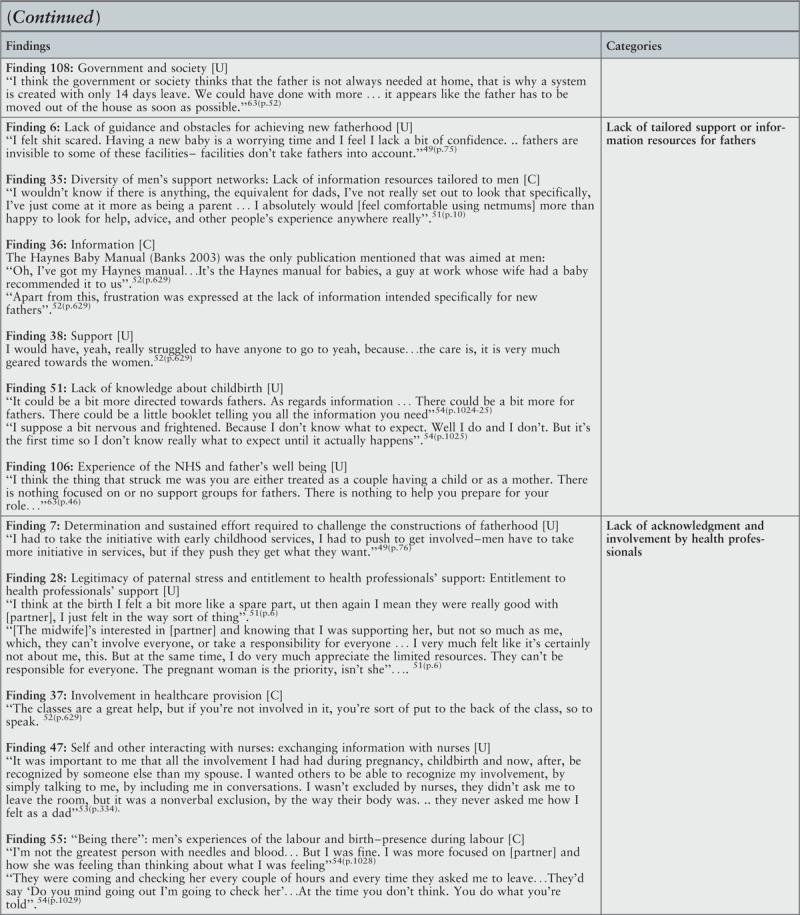

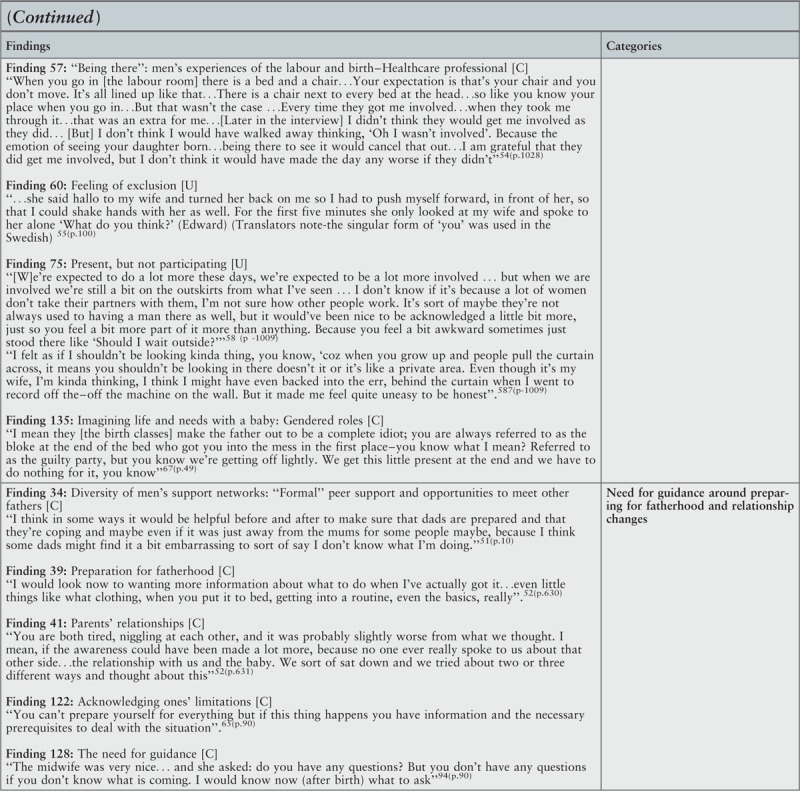

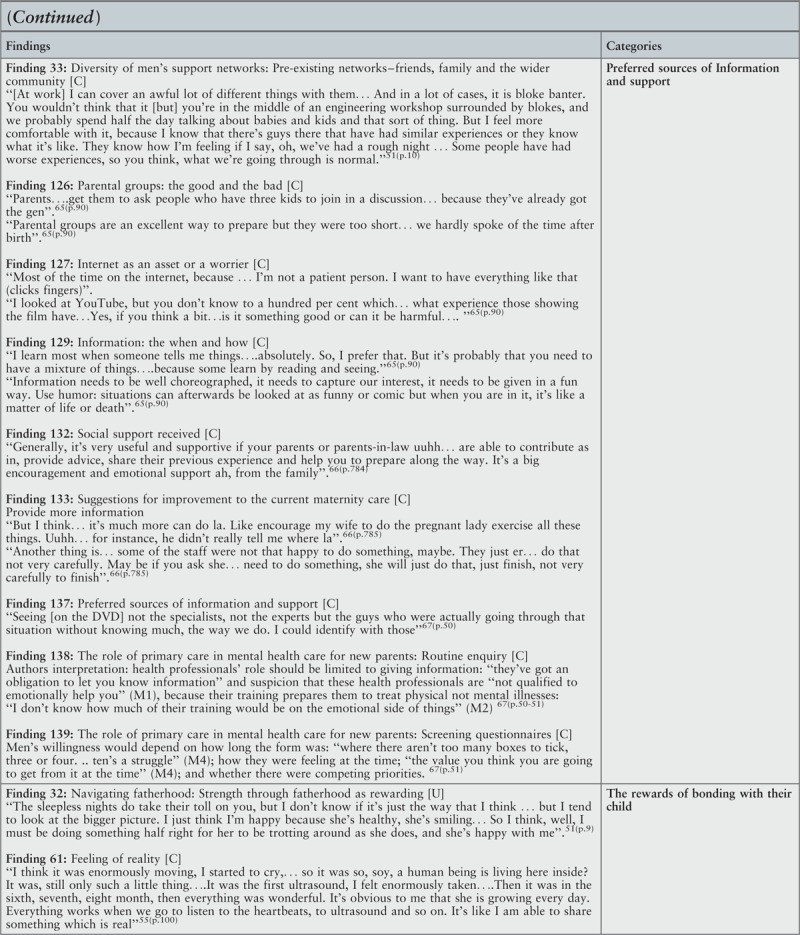

In total, 144 findings were identified and the same process was followed. Fifty-nine (41%) findings were unequivocal (U), 83 (58%) credible (C), and only two (1%) unsupported (US). As inclusion of unsupported findings is not recommended in JBI qualitative systematic reviews, the two unsupported findings were excluded from the next stages of the meta-synthesis. A full list of findings along with illustrations and levels of credibility are presented in Appendix IV. The 142 included findings were repeatedly read and reread to compare and identify similarities between them. Those found to be similar were aggregated into 23 categories as follows:

Being a father, feeling more of a man

Changed priorities, responsibility and expanded vision

Being a good enough dad and getting it right

Challenges of balancing work and the role of fatherhood

Deterioration in couple relationship

Changes to sexual relationship

Breastfeeding: a difficult experience

Struggles with bonding with the baby during pregnancy and the early days

Not knowing what to expect and fear of the unknown

Feelings of helplessness

Pushed out of the relationship and struggling to find a role

Fears relating to labor and birth

Concerns about their partner's and baby's wellbeing

Restrictions, frustrations and stresses of new fatherhood

Coping mechanisms

Societal expectations and lack of social/peer support

Lack of tailored support or information resources for fathers

Lack of acknowledgment and involvement by health professionals

Need for guidance around preparing for fatherhood and relationship changes

Preferred sources of information and support

The rewards of bonding with their child

Recognizing and adjusting to changes of parenthood

Working in partnership.

A full list of findings and categories is presented in Appendix V. The categories were further examined to identify if they could be synthesized. Seven synthesized findings were identified:

-

1.

New fatherhood identity

-

2.

Competing challenges of new fatherhood

-

3.

Negative feelings and fears

-

4.

Stress and coping

-

5.

Lack of support

-

6.

What new fathers want

-

7.

Positive aspects of fatherhood.

The ConQual1 approach to assess the confidence in the level of evidence of each synthesized finding was applied (Summary of Findings). For synthesized findings 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7, the majority of the studies received four to five “yes” responses on the ConQual identified criteria for dependability; therefore, the level of confidence remained unchanged. The findings included a mix of unequivocal and equivocal (credible) ratings, necessitating downgrading by an additional level, resulting in a ConQual score of “moderate”. For synthesized finding 6, although the majority of studies (five out of six) scored four or five for the questions on appropriateness of research conduct (meaning no change to the dependability score), the credibility score was downgraded two levels (−2) due to all findings being equivocal (credible). The ConQual score for this finding was “low”. The seven synthesized findings are presented below and the relationship between study findings, categories and synthesized findings are illustrated in Tables 2–8.

Table 2.

Synthesized finding 1: New fatherhood identity

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| What it means to be “male” [U] The perceived positive relationship between being male and the ability to father children [U] Feeling of development [U] The caring father might emerge as, in fact, the bigger bloke [C] Accomplishing an important goal in this life phase [C] Proving their ability as men [C] | Being a father, feeling more of a man | New fatherhood identity: Becoming a father gave men a new identity, which made them feel like they were fulfilling their role as “men”. They recognized that this new role came with changed priorities and responsibilities, which they welcomed; however, they often worried about being a “good father” and “getting it right”. |

| Maintaining health to meet the needs of forthcoming dependents [C] Feeling of responsibility [U] Symbolizing eternal love [C] Preparation for fatherhood [C] Expanded vision [U] Changes associated with the father's role [U] Adjusting priorities [C] Emotional changes experienced [C] | Changed priorities, responsibility and expanded vision | |

| New fathers wish to father differently from their own fathers [U] Worry about being able to manage being both a good provider and a “hands on” father [U] Wanting to cherry pick the best bits from own childhood [C] Wanting to bring baby up in best way [C] Wanting to get things right [U] Worries about being a good enough dad [U] Expanded role of good fathers [C] Dealing with internal and external pressures [C] Good father and father involvement [C] | Being a good enough dad and getting it right |

U, unequivocal; C, credible

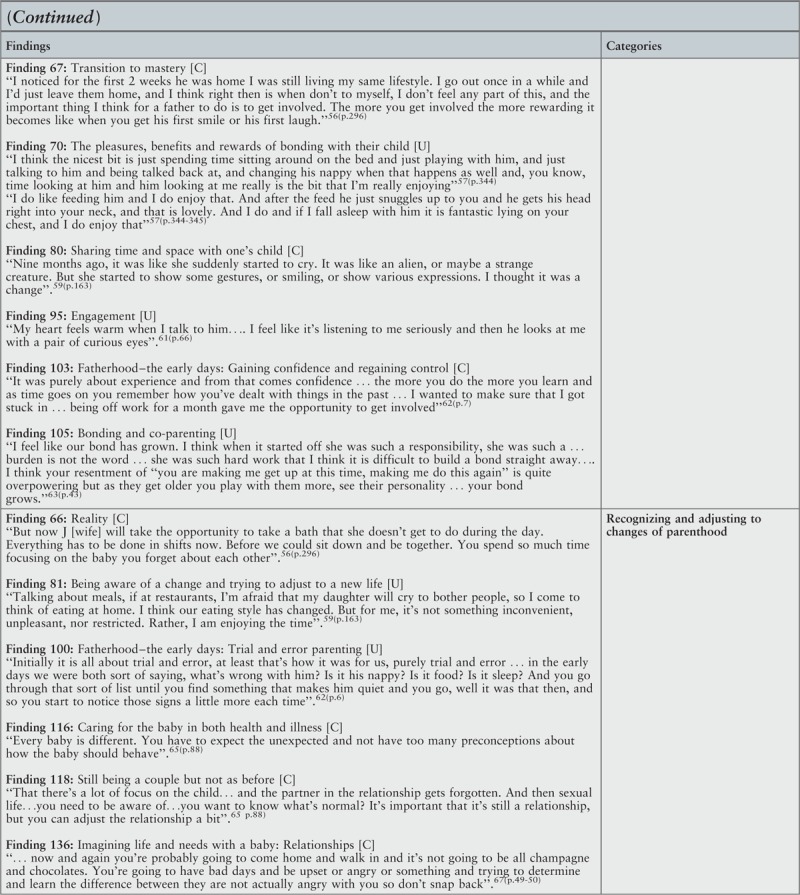

Table 8.

Synthesized finding 7: Positive aspects of fatherhood

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| Navigating fatherhood: Strength through fatherhood as rewarding [U] Feeling of reality [C] Transition to mastery [C] The pleasures, benefits and rewards of bonding with their child [U] Sharing time and space with one's child [C] Engagement [U] Fatherhood – the early days: gaining confidence and regaining control [C] Bonding and co-parenting [U] | The rewards of bonding with their child | Positive aspects of fatherhood: There were a number of positive aspects related to new fatherhood. Fathers who were involved with their child and bonded with them over time found the experience to be rewarding. Those who recognized the need for change, adjusted better to the new role, especially when they worked together with their partners. |

| Reality [C] Being aware of a change and trying to adjust to a new life [U] Fatherhood – the early days: trial and error parenting [U] Caring for the baby in both health and illness [C] Still being a couple but not as before [C] Imagining life and needs with a baby: relationships [C] | Recognizing and adjusting to changes of parenthood | |

| Feeling prepared and (changing) expectations [C] Fatherhood – the early days: she leads, I follow [C] Fatherhood – the early days: working together [C] Communicating with ones’ partner [C] Forming a fatherhood identity [C] Adaptive and supportive behaviors adopted [C] | Working in partnership |

C, credible; U, unequivocal

Synthesized finding 1: New fatherhood identity

Three categories comprising 23 findings were integrated into the first synthesized finding (Table 2). The first category, being a father, feeling more of a man, refers to how men perceived themselves as they became fathers for the first time. Their ability to father a child was described as an important achievement in their lives: “My first thought was ‘yes! I can have a baby”’.60(p.63)

Becoming a father also made them feel more masculine and “more of a man”. One father described feeling “over the moon…I suppose it's like a man thing. It's like you feel more of a man in a way. I know it sounds a bit weird but you feel more a man…You feel everything's working and you’re alright. So I was over the moon, overjoyed”.53(p.1023) While another father talked about development and growth resulting from new fatherhood: “I feel, that I’m growing, as a human being. Yes, it's what I’m doing, absolutely. And even as a man. That it's undeniably one kind of confirmation”.54(p.102)

The second category, changed priorities, responsibility and expanded vision, refers to how men acknowledged that the new role of fatherhood led to new responsibilities and priorities. Men talked about the need to change their lifestyle due to having “another person to think about”.

“You’ve got to leave your juvenile life behind, stop running around with your mates and that. You have to change it… without agreeing to it… you’ve just got no choice (laughs). Now I’ve got someone else to think about…”.64(p.89)

The changes also included taking on the provider role to ensure financial security: “ …there was something in the breadwinner factor that made me feel that I should change my priorities. It happens even before the baby is born. We are building our ‘nest’ and making more rational decisions than before”.54(p.101) “Money is also very important. We therefore have to save as much as we can. I need to work as hard as possible. Maybe I’ll need some investments as well”.60(p.66) Most men, however, welcomed these changes and felt were necessary for this new phase in their lives.

The third category, being a good enough dad and getting it right, refers to how men wanted to be a good father and often worried about “not getting it right”. Some men wanted to be more “hands on” with their child and father them differently to how they themselves were fathered: “My father was more removed, I’m much more hands on, my father sat around and did little, my experience is very different, I change nappies, make milk and get up in the middle of the night.”48(p.74)

Being a good father was seen as being present and spending time with their child: “I think being there for all their first major things is important, i.e. when they’re at school, when they go to do a nativity play, going to the nativity play, not saying no I’m too busy at work or, you know, someone will video it for me, or whatever.56(p.343)

“A parent who is prepared to put work second and family first, you know, the father who's prepared to do that, I think that's a good father.”56(p.343)

However, men often worried about not “getting things right” and not being able to fulfill the role of a good father: “I am also worried of not getting it right. Uh… do I let him play on the floor with the baby gym with all the things hanging all over the top; he's interested in that. But do I, do I leave him or not? Do… er… is that not interacting with him enough? But then, if I put him in the cot in his springy seat thing, but what am I supposed to say to him? Am I supposed just to play with him? Cuddle him? Am I supposed to? And… and I don’t naturally sort of feel, I don’t know what to do”49(p.156)

The synthesized finding summarizes how the transition to fatherhood is perceived by men. During this time a new fatherhood identity is formed, which makes them feel more masculine while accomplishing an important new phase in life.

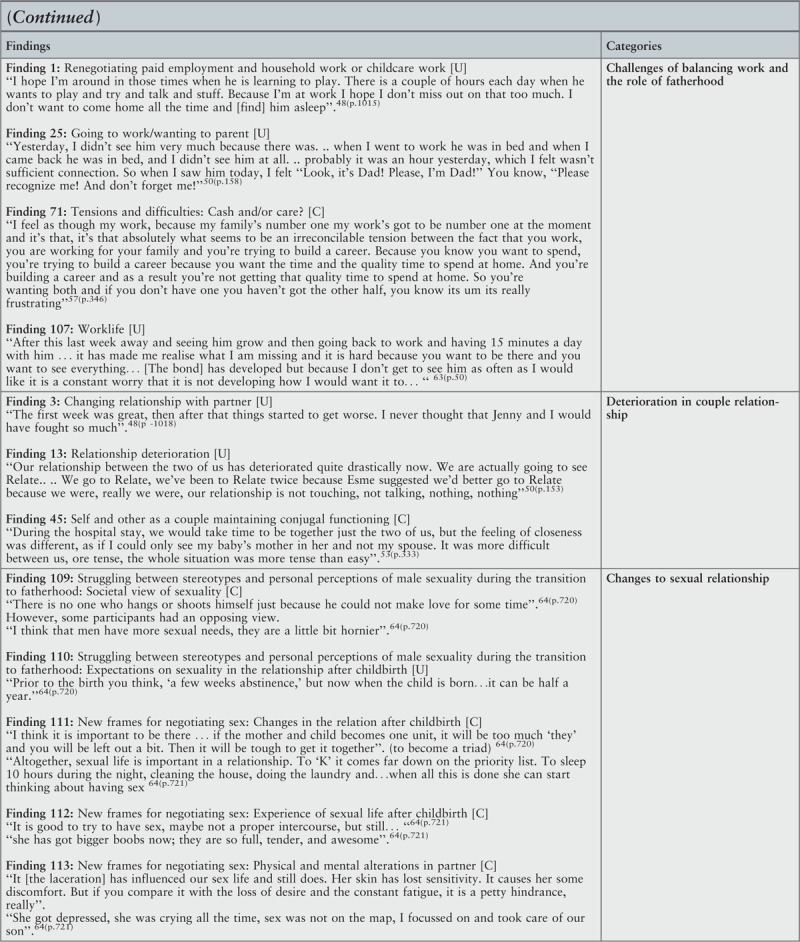

Synthesized finding 2: Competing challenges of new fatherhood

This meta-synthesis resulted from five categories, comprising 24 findings (Table 3). The first category, challenges of balancing work and the role of fatherhood, refers to the dilemma men experience as a result of having to balance their work responsibilities with being a father.

Table 3.

Synthesized finding 2: Competing challenges of new fatherhood

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| Renegotiating paid employment and household work or childcare work [U] Going to work/wanting to parent [U] Tensions and difficulties: cash and/or care? [C] Work life [U] | Challenges of balancing work and the role of fatherhood | Competing challenges of new fatherhood: Men experienced a number of competing demands as they became fathers. They had to balance work demands with the time they were able to spend with their child. They also experienced a deterioration in their relationship with their partner, which included reduced satisfaction with their sexual relationship. Expectations of new fathers often did not meet reality, especially around breastfeeding and bonding. New fathers found breastfeeding to be a more difficult experience than anticipated, while many also struggled to bond with their babies in utero and in the early days following birth. |

| Changing relationship with partner [U] Relationship deterioration [U] Maintaining conjugal functioning [C] | Deterioration in couple relationships | |

| Societal view of sexuality [C] Expectations on sexuality in the relationship after childbirth [U] Changes in the relation after childbirth [C] Experience of sexual life after childbirth [C] Physical and mental alterations in partner [C] | Changes to sexual relationship | |

| Coping with parental demands [U] Coming to terms with environmental demands [C] Breastfeeding: more challenging than expected [U] | Breastfeeding: a difficult experience | |

| Expectations and symbolic meaning of fatherhood [U] Feeling of unreality [C] On the inside, looking in [U] Feeling like a father [C] Being aware of the difference between oneself and one's wife [U] Grappling with the reality of the pregnancy and child [C] Discouraged by the inapplicability of the old ways of building relationships [C] Experiences during pregnancy: Feelings of separation [C] Challenges in transition to parenthood [C] | Struggles with bonding with the baby during pregnancy and the early days |

U, unequivocal; C, credible

“I feel as though my work, because my family's number one my work's got to be number one at the moment and it's that, it's that absolutely what seems to be an irreconcilable tension between the fact that you work, you are working for your family and you’re trying to build a career. Because you know you want to spend, you’re trying to build a career because you want the time and the quality time to spend at home. And you’re building a career and as a result you’re not getting that quality time to spend at home. So you’re wanting both and if you don’t have one you haven’t got the other half, you know its um its really frustrating”56(p.346)

Men particularly worried about “missing out” on spending time with their child, because of work responsibilities: “I hope I’m around in those times when he is learning to play. There is a couple of hours each day when he wants to play and try and talk and stuff. Because I’m at work I hope I don’t miss out on that too much. I don’t want to come home all the time and [find] him asleep”.47(p.1015)

“After this last week away and seeing him grow and then going back to work and having 15 minutes a day with him… it has made me realize what I am missing and it is hard because you want to be there and you want to see everything… [The bond] has developed but because I don’t get to see him as often as I would like it is a constant worry that it is not developing how I would want it to…”62(p.50)

The second category was deterioration in couple relationship following the birth of their child. Men reported changes in their relationship with their partner, in some cases needing additional relationship interventions following the birth of their child: “The first week was great, then after that things started to get worse. I never thought that Jenny and I would have fought so much”.47(p.1018)

“Our relationship between the two of us has deteriorated quite drastically now. We are actually going to see Relate…. We go to Relate, we’ve been to Relate twice because Esme suggested we’d better go to Relate because we were, really we were, our relationship is not touching, not talking, nothing, nothing”49(p.153)

There were also changes to sexual relationship between couples following childbirth, which formed the third category. While this category resulted from five different findings, they derived from the same study. Generally, the changes referred to a deterioration in sexual activity: “Prior to the birth you think, ‘a few weeks abstinence,’ but now when the child is born… it can be half a year.”63(p.720)

Sex was also seen as less of a priority to women than men: “Altogether, sexual life is important in a relationship. To ‘K’ it comes far down on the priority list. To sleep 10 hours during the night, cleaning the house, doing the laundry and… when all this is done she can start thinking about having sex”.63(p.721)

The fourth category, breastfeeding: a difficult experience, refers to the challenges experienced by new fathers relating specifically to breastfeeding. It was something that fathers found difficult, anxiety provoking and that they were totally unprepared for: “It was one feeding after another; I was under the impression of having no respite. I knew it would be like that, but I still found it difficult.”52(p.333)

“I have to say that there I was not prepared at all but had a mental picture that it's just a matter of laying the baby to the breast and it all works. When it didn’t work you stood there: aha, what the hell do we do now?”64(p.88)

Fathers reported the experience to be more challenging than they had anticipated, which left them feeling “helpless”: “Breastfeeding was what I found most difficult. I didn’t know how to help, I felt useless.”52(p.333)

The fifth category was struggles with bonding with the baby during pregnancy and the early days. During the pregnancy period, men talked about not “feeling like a father” straightaway: “I don’t feel myself as a father, or how should I put it… I don’t feel it consciously. It was not like going up stairs and at a certain point, ‘I’m a father from today!’ Such a feeling didn’t come to me. It was more like going up a slope”.58(p.162)

They struggled to bond with their unborn child as the baby was not growing inside them, “ …My wife can share her feelings with me. Sometimes she says the baby is moving inside her. But, actually, as a third person, I can’t imagine what that's like”.60(p.65)

The struggles to bond with their baby continued after the birth. Many expected that they would bond immediately with the child and were surprised when that was not the case: “I thought as a father there would be a bond there straight away with the child. I thought it would just come naturally. I thought because he was mine I was going to be immediately attracted to this child and love would just come naturally. I was surprised I wasn’t overcome with feelings for him straight away”47(p.1017).

There appeared to be a level of disappointment when the fathers’ expectations about bonding with their baby did not meet reality. Many fathers felt that the bond between the mother and child was much stronger.

Therefore, the current synthesized finding summarizes the various challenges experienced by men during their transition to fatherhood.

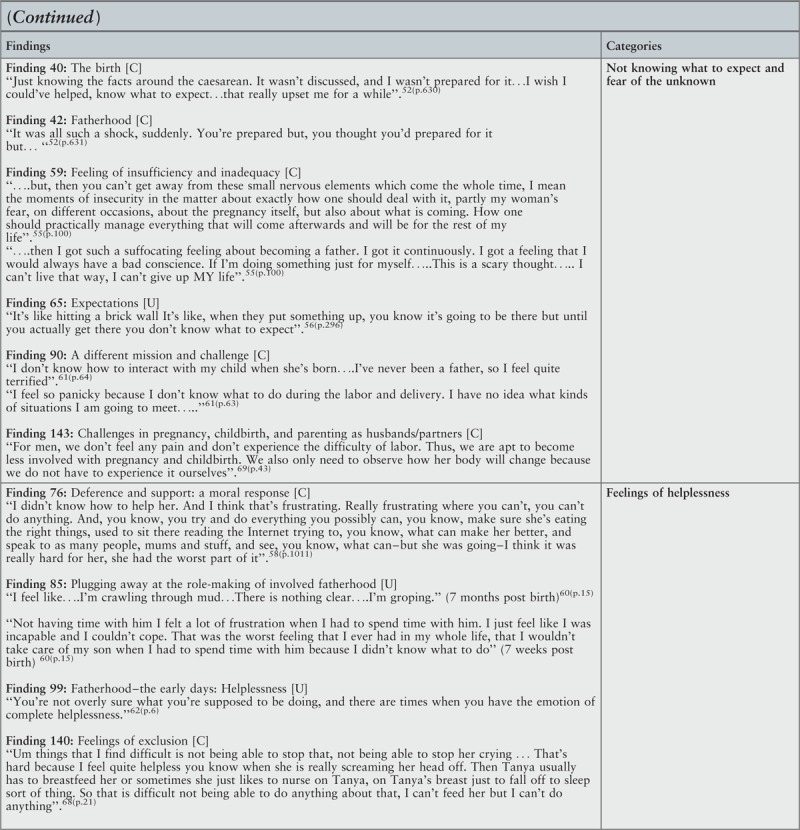

Synthesized finding 3: Negative feelings and fears

This meta-synthesis resulted from five categories, with 26 findings (Table 4). The first category, not knowing what to expect and fear of the unknown, relates to men's expectations of labor, birth and the new father role. Men talked about feeling nervous and unprepared due to not having any previous experience: “I don’t know how to interact with my child when she's born… I’ve never been a father, so I feel quite terrified”.60(p.64) They often did not know what to expect, “It's like hitting a brick wall It's like, when they put something up, you know it's going to be there but until you actually get there you don’t know what to expect”.55(p.296)

Table 4.

Synthesized finding 3: Negative feelings and fears

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| The birth [C] Fatherhood [C] Feeling of insufficiency and inadequacy [C] Expectations [U] A different mission and challenge [C] Challenges in pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting as husbands/partners [C] | Not knowing what to expect and fear of the unknown | Negative feelings and fears: Expectant and new fathers experienced a range of fears and often did not know what to expect from the processes involved during the transition to fatherhood. This resulted in fathers feeling helpless, pushed out of the relationship and struggling to find a role. Men experienced specific fears relating to their partner's labor and the birthing process. They often worried about the wellbeing of their partner and baby throughout the perinatal period. |

| Deference and support: a moral response [C] Plugging away at the role-making of involved fatherhood [U] Fatherhood – the early days: helplessness [U] Feelings of exclusion [C] | Feelings of helplessness | |

| Excitement thwarted by partner's reticence [C] The focus shifting from us to him [U] Feeling left/pushed out [U] Struggling to find a role [U] Apprehension about criticism [C] Helping out or “full involvement”? Fairness, equity and decision making [U] | Pushed out of the relationship and struggling to find a role | |

| Aspects of the labor and birth [U] “Being there”: men's experiences of the labor and birth – cesarean [U] | Fears relating to labor and birth | |

| Childbirth perceived as a shared experience and being there [C] Realizing oneself as a husband [C] Finding the wife's pregnancy and delivery for the first time to be an impressive experience [C] Ending their wives’ discomfort [C] The health status of his wife and fetus [C] The wonder of fetal movement [C] Imagining life and needs with a baby: fantasies and fears [C] Making active efforts in preparation for childbirth in a foreign country [C] | Concerns about their partner's and baby's wellbeing |

U, unequivocal; C, credible

This uncertainty often resulted in men feeling frustrated, excluded and uncertain about how they could help, which formed the second category of feelings of helplessness: “You’re not overly sure what you’re supposed to be doing, and there are times when you have the emotion of complete helplessness.”61(p.6)

“Um things that I find difficult is not being able to stop that, not being able to stop her crying… That's hard because I feel quite helpless you know when she is really screaming her head off. Then Tanya usually has to breastfeed her or sometimes she just likes to nurse on Tanya, on Tanya's breast just to fall off to sleep sort of thing. So that is difficult not being able to do anything about that, I can’t feed her but I can’t do anything”.67(p.21)

The third category was pushed out of the relationship and struggling to find a role. Men described not feeling involved with their partner's pregnancy and the birth due to not being able to physically experience the changes: “And I felt really out of the whole thing… I wasn’t involved in that (the pregnancy)… I couldn’t be because it wasn’t in me… and all I could do was be there for her”.49(p.155) Fathers wanted to be involved in decision making processes but were often left excluded, struggling to find a role.

The fourth category, fears relating to labor and birth, referred to the specific concerns expressed by men relating to the birthing process. All three findings in this category were derived from the same study. While men wanted to support their partner through labor and birth, they were often concerned about their ability to deal with it: “First and foremost I hope I don’t pass out. Because I don’t like needles and all that sort of stuff… It just sends me a bit funny… I’m hoping I won’t pass out anyway. But you never know”.53(p.1025)

The fifth category related to men's concerns about their partner's and baby's wellbeing. Men worried about their partner and baby during pregnancy, birth and the early days: “I would like to say that soon my wife will not be suffering any longer. She's been through a hard time; before she became pregnant, and now, while she is expecting this baby. As far as I know, she has gone through many hurdles such as examinations and extracting her legs. I’m not even sure if I could do the whole thing once and she tried many times. So, she is a great woman… Now it's successful and she’ll never have to go through any more suffering!”60(p.63)

All five categories in this synthesized finding related to negative feelings and fears experienced by men during their transition to fatherhood.

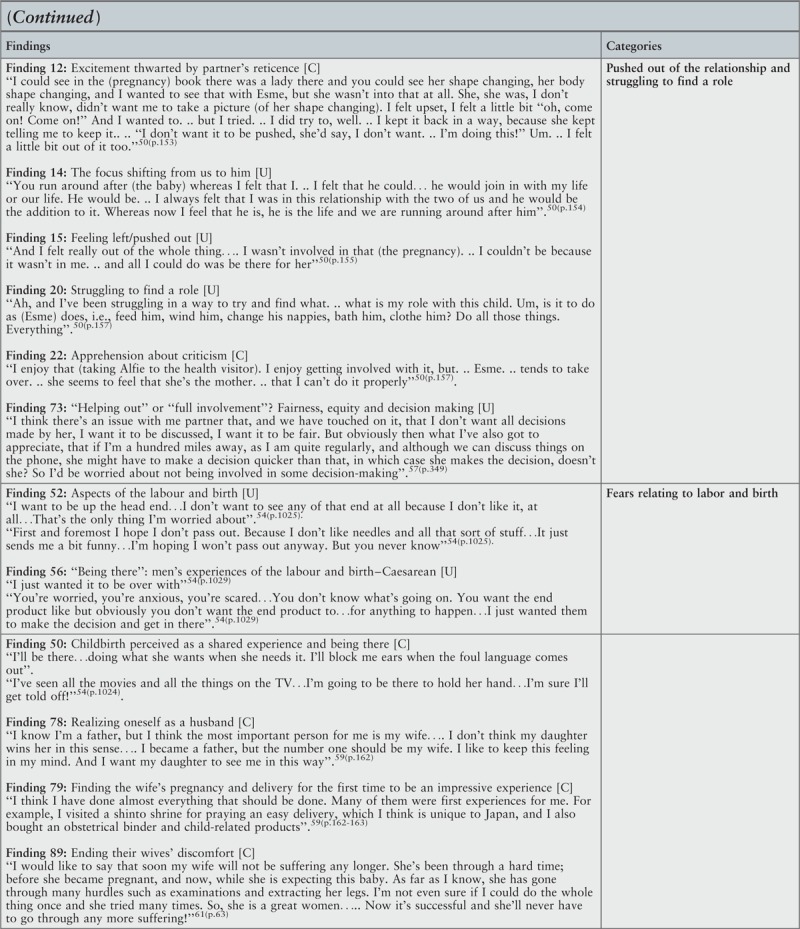

Synthesized finding 4: Stress and coping

This meta-synthesis resulted from two categories, comprising 15 findings (Table 5). The first category was restrictions, frustrations and stresses of new fatherhood. Many fathers acknowledged the restrictions of their new role and not being able to do all the things that they wanted to do, which often led to frustration.

Table 5.

Synthesized finding 4: Stress and coping

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| Challenges of combining new fatherhood and traditional narratives [U] Life's restrictions on becoming a parent [U] Articulating and attributing stress [U] Protecting the partnership [U] Coming to terms with the physical and emotional changes during the postpartum period [U] Whose needs? Whose values? Selflessness and autonomy in dialogue [C] Being tired and bound [C] Understanding emotional reactions [C] | Restrictions, frustrations and stresses of new fatherhood | Stress and coping: The role restrictions and changes in lifestyle resulted in increased stress levels in new fathers, which manifested as tiredness, irritability and frustration. Fathers used denial or escape activities, such as smoking, working longer hours or listening to music as coping techniques. |

| Engaging with traditional fatherhood [U] Not engaging with fatherhood [U] What is expected of men is different to how I feel! [C] Legitimacy of paternal stress and entitlement to health professionals’ support: Symptoms and manifestation [U] Managing stress through distraction, denial and release [U] Disclosing personal difficulties [U] Adjustment [C] | Signs of stress and coping mechanisms |

U, unequivocal; C, credible

“One of the feelings I have been getting is of… I can’t do all the things I want to do. I found it very frustrating… I’ve been on leave for quite a lot recently… I find it very frustrating when I can’t, I can’t get to go and do something I want to do like… like the washing… something simple like that”.49(p.158)

“Um… I didn’t quite understand, I don’t think I quite understood how full on babies are. Er… they’re 100% and more. They take over your life and there's no… you don’t have a life in effect really”.49(p.158)

New fathers experienced tiredness, sleeplessness, exhaustion and irritation,52,56,65 which increased their stress levels in the postnatal period. One father described stress as the “non-stop-ness of it”50(p.5) due to having a stressful job and no time to relax.

Signs of stress and coping mechanisms was the second category. Fathers talked about feeling grumpy and snappy as a result of the tiredness and stress, which they often managed through distraction techniques, such as getting engrossed in work, listening to music or smoking. “I’m probably the sort of bloke who actually just says, ‘oh I’m quite forgetful, so I can forget I’ve had the worst night ever’. I just try and forget it. So that's probably my coping mechanism. It's just, trying to forget it and I generally do. And then, I guess, I’ve found in some ways, work quite helpful in that respect, because you can have a crazy night where you have no idea what's going on with [son's name], but I can go to work and I feel fine. I’m in control here, I know what to do. There's people who I can actually communicate with, they’ll do what I ask them to do and vice versa. So I’m probably not the best example, the best person to ask, because I think I just choose to ignore. I’m probably more of an ignorer, which isn’t probably that helpful for [partner's name].”50(p.8)

“… She often complains that I download ‘noise’ from the internet. She thinks it's not music. I feel bad when she keeps going on at me about this. I just go outside and have a smoke”.60(p.65)

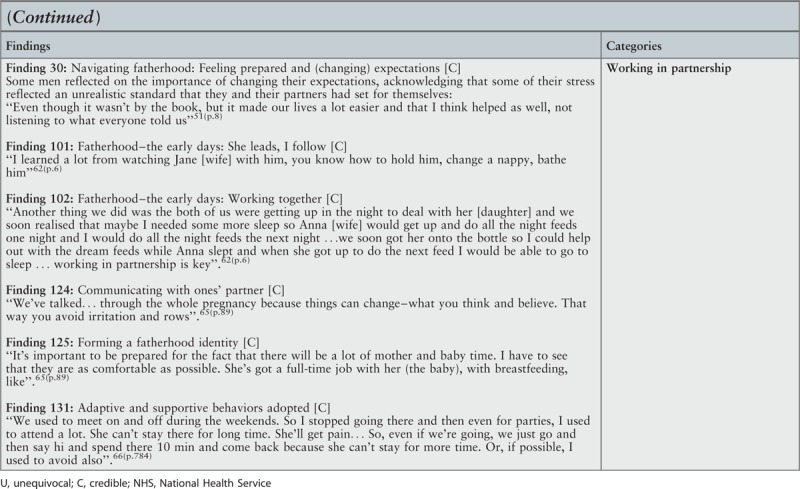

Synthesized finding 5: Lack of support

This meta-synthesis was derived from 20 findings and three categories: societal expectations and lack of social/peer support, lack of tailored support or information resources for fathers, and lack of acknowledgment and involvement by health professionals (Table 6).

Table 6.

Synthesized finding 5: Lack of support

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| Male friends at work unable to offer support [C] Social support [U] Feeling of social changes [U] Struggling for recognition as a parent from mate, co-workers, friends, family, baby and society [U] Government and society [U] | Societal expectations and lack of social/peer support | Lack of support: New fathers lacked support from their male work colleagues and peers. The main barriers to new fathers accessing or receiving adequate support were related to the lack of resources aimed specifically at men. Men were often not viewed or treated as equal partners and lacked acknowledgment or involvement by health professionals during their transition to fatherhood. |

| Lack of guidance and obstacles for achieving new fatherhood [U] Diversity of men's support networks: lack of information resources tailored to men [C] Information [C] Support [U] Lack of knowledge about childbirth [U] Experience of the NHS and father's wellbeing [U] | Lack of tailored support or information resources for fathers | |

| Determination and sustained effort required to challenge the constructions of fatherhood [U] Entitlement to health professionals’ support [U] Involvement in healthcare provision [C] Self and other interacting with nurses: exchanging information with nurses [U] “Being there”: men's experiences of the labor and birth – presence during labor [C] “Being there”: men's experiences of the labor and birth – healthcare professional [C] Feeling of exclusion [U] Present, but not participating [U] Imagining life and needs with a baby: gendered roles [C] | Lack of acknowledgment and involvement by health professionals |

U, unequivocal; C, credible; NHS, National Health Service

Many men talked about the lack of understanding from male friends and work colleagues about the challenges associated with their new role as fathers. They described not finding “anybody that is real understanding”,59(p.14) feeling they had “drifted incredibly far apart” from friends54(p.101) and how peers “just take the mickey really keep telling me my life as I know it is over”.53(p.1026)

The lack of tailored support and information resources for fathers was apparent. Men were unaware of resources designed specifically for “dads”, and felt services were mainly aimed at women. Many felt excluded by health professionals and described feeling like a “spare part”50(p.10) and made “out to be a complete idiot”.66(p.49) They were often not acknowledged as equal partners in the process as health professionals mainly focused on the mother. Many men, however, accepted this, as they felt their partners’ needs should be prioritized when healthcare resources are limited.

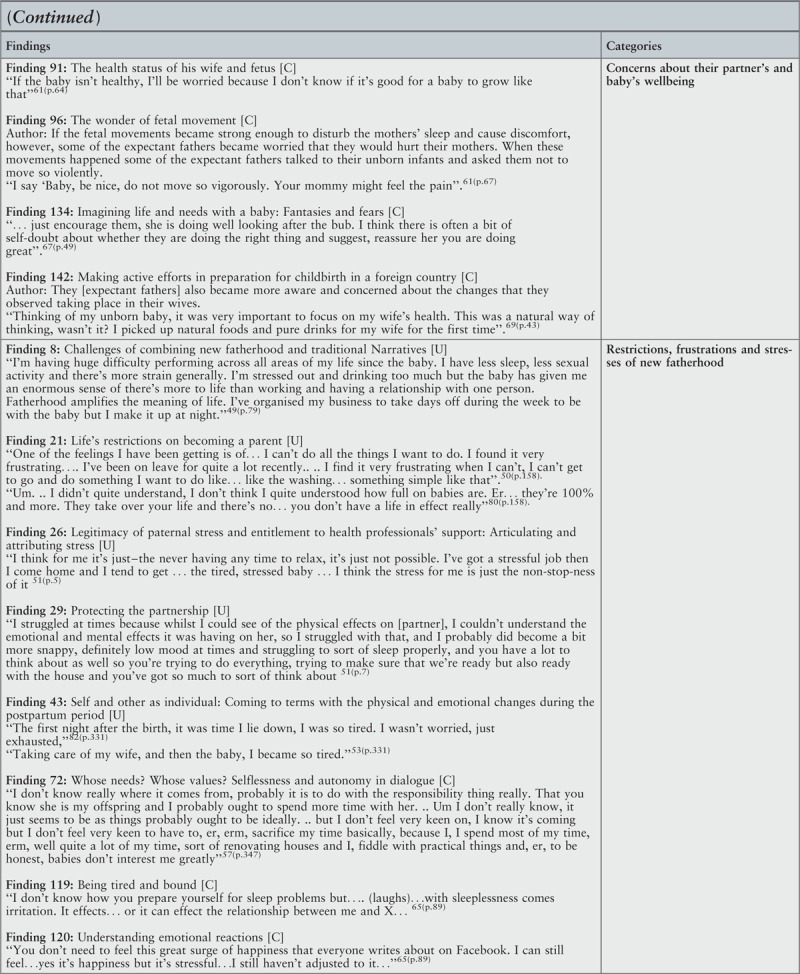

Synthesized finding 6: What new fathers want

Two categories including 14 findings were integrated into the sixth synthesized finding (Table 7). The first category, need for guidance around preparing for fatherhood and relationship changes, refers to the identified perceived needs of first time fathers. They wanted practical advice around clothing, feeding and routines for the baby, as well as information around changes in their relationship with their partner following the birth of the baby, including sexual relationships.

Table 7.

Synthesized finding 6: What new fathers want

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

| “Formal” peer support and opportunities to meet other fathers [C] Preparation for fatherhood [C] Parents’ relationships [C] Acknowledging ones’ limitations [C] The need for guidance [C] | Need for guidance around preparing for fatherhood and relationship changes | What new fathers want: More guidance and support around the preparation for fatherhood, and relationship changes with their partner were identified as needs for first-time fathers. Having a variety of support mechanisms in place to include parenting groups involving others with similar experiences, father-friendly resources and father-inclusive services were useful strategies to support their mental health and wellbeing. |

| Pre-existing networks – friends, family and the wider community [C] Parental groups: the good and the bad [C] Internet as an asset or a worrier [C] Information: the when and how [C] Social support received [C] Suggestions for improvement to the current maternity care [C] Preferred sources of information and support [C] The role of primary care in mental health care for new parents: routine enquiry [C] The role of primary care in mental health care for new parents: screening questionnaires [C] | Preferred sources of information and support |

C, credible

“I would look now to wanting more information about what to do when I’ve actually got it… even little things like what clothing, when you put it to bed, getting into a routine, even the basics, really”.51(p.630)

“You are both tired, niggling at each other, and it was probably slightly worse from what we thought. I mean, if the awareness could have been made a lot more, because no one ever really spoke to us about that other side…the relationship with us and the baby. We sort of sat down and we tried about two or three different ways and thought about this”.51(p.631)

“The midwife was very nice… and she asked: do you have any questions? But you don’t have any questions if you don’t know what is coming. I would know now (after birth) what to ask”.64(p.90)

Fathers identified a number of different sources of information and support that would be helpful, which formed the second category, preferred sources of information and support. Many valued face to face contact, where information relating to the transition to parenthood was provided by a professional but felt that a variety of methods should be available to fathers.

“I learn most when someone tells me things… absolutely. So, I prefer that. But it's probably that you need to have a mixture of things… because some learn by reading and seeing”.64(p.90)

Others talked about having access to parenting groups or DVDs involving other parents, with similar experiences: “Seeing [on the DVD] not the specialists, not the experts but the guys who were actually going through that situation without knowing much, the way we do. I could identify with those”.66(p.50)

One father talked about the importance of making the information fun and humorous to capture their interest, while another talked about the dilemmas of using the internet due to not knowing how credible the information is: “Information needs to be well choreographed, it needs to capture our interest, it needs to be given in a fun way. Use humor: situations can afterwards be looked at as funny or comic but when you are in it, it's like a matter of life or death”.64(p.90)

“I looked at YouTube, but you don’t know to a hundred percent which… what experience those showing the film have…Yes, if you think a bit… is it something good or can it be harmful… ”64(p.90)

Family members, parents and parents-in-law, were seen as good sources of support, where available. Routine enquiry about emotional wellbeing, however, was questioned, as fathers were uncertain about their primary care professionals’ training around emotional wellbeing and ability to provide adequate support. In regard to screening questionnaires, men's willingness to complete them would depend on how long the form was, how they were feeling at the time, their perceived value of completing it at the time and if there were competing priorities.

Synthesized finding 7: Positive aspects of fatherhood

This meta-synthesis resulted from three categories of 20 findings on positive aspects of transition to fatherhood (Table 8). The first category related to the rewards of bonding with their child. The more time men spent with their children, the more confident they felt as fathers, and they reported the experience to be extremely rewarding: “The sleepless nights do take their toll on you, but I don’t know if it's just the way that I think… but I tend to look at the bigger picture. I just think I’m happy because she's healthy, she's smiling… So I think, well, I must be doing something half right for her to be trotting around as she does, and she's happy with me”.50(p.9)

“I think the nicest bit is just spending time sitting around on the bed and just playing with him, and just talking to him and being talked back at, and changing his nappy when that happens as well and, you know, time looking at him and him looking at me really is the bit that I’m really enjoying”.56(p.344)

The second category, recognizing and adjusting to changes of parenthood, refers to fathers who recognized and accepted the changes to their lifestyles. They also appeared to make better adjustments to the new role of fatherhood: “Talking about meals, if at restaurants, I’m afraid that my daughter will cry to bother people, so I come to think of eating at home. I think our eating style has changed. But for me, it's not something inconvenient, unpleasant, nor restricted. Rather, I am enjoying the time”.58(p.163)“Initially it is all about trial and error, at least that's how it was for us, purely trial and error… in the early days we were both sort of saying, what's wrong with him? Is it his nappy? Is it food? Is it sleep? And you go through that sort of list until you find something that makes him quiet and you go, well it was that then, and so you start to notice those signs a little more each time”.61(p.6)

The third category, working in partnership, refers to couples who communicated well and worked together to address the challenges of parenthood.50,61,65,66

“Another thing we did was the both of us were getting up in the night to deal with [our daughter] and we soon realized that maybe I needed some more sleep so Anna [wife] would get up and do all the night feeds one night and I would do all the night feeds the next night… we soon got her onto the bottle so I could help out with the dream feeds while Anna slept and when she got up to do the next feed I would be able to go to sleep… working in partnership is key”.61(p.6)

“We’ve talked… through the whole pregnancy because things can change – what you think and believe. That way you avoid irritation and rows”.64(p.89)

Discussion

This qualitative systematic review aimed to explore the experiences and needs of first time fathers in relation to their mental health and wellbeing during the transition to fatherhood. Twenty-two papers were included in the review after a rigorous search and inclusion process. While all included papers focused on the general experiences of expectant or new fathers, only three specifically addressed the mental health and wellbeing of first time fathers. Dallos and Nokes49 explored the experience of a first time father who encountered psychological difficulties following the birth of their baby; Darwin et al.50 looked at fathers’ views and experiences of paternal perinatal mental health; and Rowe et al.66 investigated first time expectant couples’ anticipated needs and preferred sources of mental health information and support. The remaining papers, although focused on general experiences of first time fathers did report on factors that affected their mental health and wellbeing in line with the review objectives.

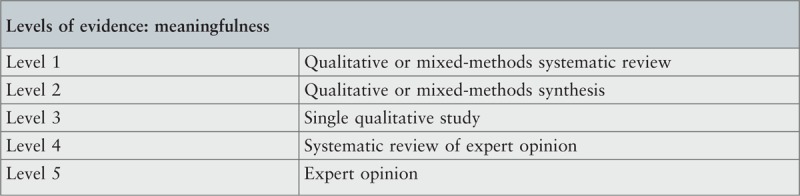

All included papers were of moderate to high quality (scores 5–10) based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research. However, when ConQual criteria1 determining dependability were considered in conjunction with criteria determining credibility, the level of evidence for six of the synthesized findings were rated as moderate, and one synthesized finding was rated as low. This discussion will examine each synthesized finding and consider implications for practice and further research.

The synthesized findings described men's experiences of first time fatherhood characterized by the formation of fatherhood identity, the competing challenges of their new role and the negative feelings and fears arising from the changes. For many new fathers the transition to fatherhood was the ”best experience” in their lives.65 The ability to father a child made men feel like they were accomplishing an important phase in their lives,54,60 which made them feel more masculine and “more of a man”.53,56 While their new role came with additional responsibilities, it gave men an expanded vision for the future.53,54,60,64 In addition, most men wanted to be good fathers and worried about “not getting it right”. The concept of “good fathering” was linked to their ability to financially provide for their child, supporting previous study findings where fathers viewed their financial duty as part of their identity and self-worth.69

The additional responsibilities and pressures to be a “good father” and meet expectations as a “father” and a “man” impact on men's mental health and wellbeing, particularly as they become a father for the first time.26 The current review found that men faced competing challenges during their transition to fatherhood and worried about “missing out” on moments with their child due to work demands and responsibilities.47,49,56 This is similar to the findings of a literature review in which fathers were reported to find the year following their child's birth particularly challenging due to the conflicting needs to balance personal and work-related necessities with their new role as a parent, meet emotional and relational needs of their family, and deal with societal and economic pressures.24

An important finding of the current review was that many men experienced a deterioration in their relationship with their partner following the birth of their child,47,49,52 including changes in their sexual relationships.64 This is not uncommon as the reduction in positive communication between couples following birth has been linked to a decline in relationship and marital satisfaction as well as an increase in conflict.70,71,72,73,74 In a study by Darwin et al.50, new fathers’ lack of sleep and emotional exhaustion led to increased levels of stress, which also impacted negatively on couple relationships as couples spent less time together and received less emotional support from one another. If relationships between couples following the birth of their child are fraught, postnatal depression may be more likely to develop in both parents in the first year of birth.75 Poor couple relationships and satisfaction are risk factors that have previously been associated with anxiety and depression in men during and following the period of transition to fatherhood.12,13,35,36 Although men talked about changes to their sexual relationships with their partner following the birth of their child,63 this was not necessarily perceived as a negative aspect. However, findings from this review show that new fathers would have preferred to know about some these possible challenges before the birth, so that they could be prepared for such relationship changes.

Another challenge experienced by new fathers in the review was related to breastfeeding. It was something that fathers found anxiety provoking and that they were totally unprepared for in terms of how to support their partner.53,65 Fathers reported experiences to be more challenging than they had anticipated, which left them feeling “helpless”. This suggests that fathers need appropriate information about breastfeeding prior to the birth of their baby and planned, ongoing support following the birth to ensure that they are well informed and can better support their partners. These findings were consistent with previous research which suggests that the attributes of positive father support in relation to breastfeeding is dependent on the father's knowledge about breastfeeding, their attitudes to breastfeeding, their involvement in the decision-making process about breastfeeding and their ability to provide practical and emotional support to their partner.76 There are a number of other benefits in providing fathers with this support: a woman's decision to breastfeed is often influenced by her partner's attitudes and behaviors towards breastfeeding;77 women feel more confident and capable about breastfeeding when their partner is supportive and involved, and breastfeeding is likely to be more successful.78 Successful breastfeeding also has the potential to positively influence the relationship between the parents.77

During the antenatal period, men described not “feeling like a father” straightaway58(p.162) and struggled to bond with their unborn child.60(p.65) Their struggles to bond with their baby continued after birth. This is important, with increasing evidence of the important role fathers’ play, not only in the lives of their partners, but in the health and wellbeing of their children. Fathers who are affectionate, supportive and involved, can contribute positively to their child's cognitive, language and social development.79 Children who have more positive relationships with their fathers tend to have fewer behavioral problems at school,80 which is strongly linked with higher educational attainment, especially in relation to their levels of literacy.81-83

Expectant and new fathers experienced negative feelings and fears relating to not knowing what to expect of their roles, leaving them feeling nervous and unprepared. This uncertainty often resulted in men feeling helpless and excluded, similar to findings reported by Hildingsson and Thomas,84 who found new fathers experienced negative feelings about the pregnancy, the upcoming birth and the first weeks of fatherhood with a newborn baby. In the current review, men also expressed fears relating to labor and birth, as well as concerns about their partner's and baby's wellbeing. This is in line with findings of Hanson et al.85 that, before the birth, fathers often expressed fear for the safety of their partner and the baby, anxiety and fear about observing their partner in pain, feelings of helplessness, lack of knowledge about the birthing process and concerns about risks of interventions such as operative delivery, limited finances and parenting skills. Similarly, in the recent quantitative systematic review by Philpott et al., stress levels in fathers were found to increase in the antenatal period due to negative feelings about the pregnancy, role restrictions related to becoming a father, fear of childbirth and feelings of incompetence about infant care.23 High anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy were the most significant predictors of depression in men in the postnatal period,7 highlighting the need for better information and support for expectant fathers in the antenatal and postnatal period.