Abstract

Background

Chronic Achilles tendinopathy is common in the general population, and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is seeing increased use to treat this problem. However, studies disagree as to whether PRP confers a beneficial effect for chronic Achilles tendinopathy, and no one to our knowledge has pooled the available randomized trials in a formal meta-analysis to try to reconcile those differences.

Questions/purposes

In the setting of a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), we asked: Does PRP plus eccentric strength training result in (1) greater improvements in Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment-Achilles (VISA-A) scores; (2) differences in tendon thickness; or (3) differences in color Doppler activity compared with placebo (saline) injections plus eccentric strength training in patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy?

Methods

A search of peer-reviewed articles was conducted to identify all RCTs using PRP injection with eccentric training for chronic Achilles tendinopathy in the electronic databases of PubMed, Web of Science (SCI-E/SSCI/A&HCI), and EMBASE from January 1981 to August 2017. Results were limited to human RCTs and published in all languages. Two reviewers assessed study quality using the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool. All the included studies had low risk of bias. The primary endpoint was improvement in the VISA-A score, which ranges from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores representing increased activity and less pain; we considered the minimum clinically important difference on the VISA-A to be 12 points. Secondary outcomes were tendon thickness change (with a thicker tendon representing more severe disease), color Doppler activity (with more activity representing a poorer result), and other functional measures (such as pain and return to sports activity). Four RCTs involving 170 participants were eligible and included 85 participants treated with PRP injection and eccentric training and 85 treated with saline injection and eccentric training. The patients in both PRP and placebo (saline) groups seemed comparable at baseline. We assessed for publication bias using a funnel plot and saw no evidence of publication bias. Based on previous studies, we had 80% power to detect a 12-point difference on the VISA-A score with the available sample size in each group.

Results

With the numbers available, there was no difference between the PRP and saline groups regarding the primary outcome (VISA-A score: mean difference [MD], 5.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.7 to 11.3; p = 0.085). Likewise, we found no difference between the PRP and saline groups in terms of our secondary outcomes of tendon thickness change (MD, 0.2 mm; 95% CI, 0.6-1.0 mm; p = 0.663) and color Doppler activity (MD, 0.1; 95% CI, -0.7 to 0.4; p = 0.695).

Conclusions

PRP injection with eccentric training did not improve VISA-A scores, reduce tendon thickness, or reduce color Doppler activity in patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy compared with saline injection. Larger randomized trials are needed to confirm these results, but until or unless a clear benefit has been demonstrated in favor of the new treatment, we cannot recommend it for general use.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy is common and difficult to manage. Several studies have reported that Achilles tendinopathy in runners accounts for 6% to 18% of all injuries [10, 35]. Although multiple treatment approaches are in common use, there is general agreement that progressive tendon loading [3, 26], in particular eccentric strengthening [1, 3], is important. Other treatments have been described, including shock wave treatment, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and glucocorticoid injections, autologous blood, polidocanol, botulinum toxin, and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) [22]; however, best practices remain poorly defined.

PRP is defined as a platelet-rich concentrate with platelet levels greater than baseline when compared with whole blood. The potential uses of PRP extend from skin and wound healing to the treatment of tendinopathy and osteoarthritis. There is widespread interest in the use of PRP in tendinopathy treatment [8]. The mechanism is believed to be related to the actions of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-β (TGF- β), and insulin-like growth factor, which may promote a healing response [15, 21, 30]. One of the main advantages of PRP is that it is autologous and so it is believed to have almost no side effects [11].

However, the few Level I randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have been published have not found clear evidence that it decreases pain or improves function with PRP compared with placebo in patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy [9, 11]. Only one high-quality RCT study has reported more promising results when examining the effect of PRP on chronic Achilles tendinopathy [5]. However, to our knowledge, no one has pooled the data in a formal meta-analysis to try to reconcile those differences.

We therefore performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to answer the following questions: Does PRP plus eccentric strength training result in (1) greater improvements in Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment-Achilles (VISA-A) scores; (2) differences in tendon thickness; or (3) differences in color Doppler activity compared with placebo (saline) injections plus eccentric strength training in patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy?

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Criteria

Our study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the PRISMA-IPD Statement [25, 34].

We conducted a thorough search of peer-reviewed articles in the electronic databases of PubMed, Web of Science (SCI-E/SSCI/A&HCI), and EMBASE to identify all RCTs using PRP injection with eccentric training for chronic Achilles tendinopathy from January 1981 to August 2017. The keywords “Achilles OR Achilles tendinopathy” and “PRP OR platelet-rich plasma OR platelet gel OR platelet derived OR platelet concentrate” were combined and results were limited to human RCTs and published in English. We certified that our institution approved the reporting of this investigation and this investigation was conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

The retrieved articles were initially screened for relevance by the title and abstract. Articles were included if they met the following criteria: (1) RCTs; (2) trials enrolling adults diagnosed with chronic Achilles tendinopathy; (3) trials that compared PRP injection with saline injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy; and (4) VISA-A score, tendon thickness change, color Doppler activity, and other functional measures (eg, pain and return to sports activity). Exclusion criteria were case-control studies, case reports, studies without abstracts, patient age < 18 years, glucocorticoid injection within the last 6 months, Achilles tendon rupture or tear, previous Achilles tendon surgery, and known inflammatory diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or inflammatory bowel). We also hand-searched the bibliographies of included trials as well as the proceedings of related conference and meeting abstracts. Only full-length published articles were included in this study.

The full text of the remaining articles was extracted by one reviewer (Y-JZ) and checked by a second reviewer (P-CG) based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [17]. Because it was accepted that the inclusion of trials with a high risk of bias might distort the results of a meta-analysis [16, 25], we also made assessment of risk of bias for all the included studies including selection bias, performance bias, incomplete attrition bias, detection bias, and reporting bias. Moreover, an additional quantification of the degree of possible bias was performed by the modified Coleman methodology score [7]. We used 10 criteria to assess the methodology of the studies reviewed. Each study was scored for each of the 10 criteria to give a total Coleman methodology score between 0 and 100. A perfect score of 100 represents a study design that largely avoids the influence of chance, different biases, and confounding factors [8]. Level of evidence for all included studies was determined (see http://handbook.cochrane.org/).

Data were collected from the remaining high-quality articles, including authors, number of patients, mean age, injection procedure, and clinical outcomes including VISA-A score, tendon thickness change, color Doppler activity, pain, and returning to sports activity.

The technique used in all PRP groups of included studies was described as single or multiple injections under ultrasonographic guidance, intratendinous and peritendinous, with or without local anesthetic. After the injection, all patients received the standardized rehabilitation and eccentric program recommended by Chan et al. [6] and Alfredson and Ohberg [2]. During the first 48 hours after the injection, patients were only allowed to walk short distances indoors. From the third to seventh day, walking up to 30 minutes was allowed. In the second week, the exercise program was started and consisted of 1 week of stretching exercises and then a 12-week daily eccentric exercise program (180 repetitions) [2]. All patients were instructed to avoid weightbearing sporting activities for the first 4 weeks. After 4 weeks, a gradual return to sports activities was encouraged.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint was improvement in the VISA-A score, which ranges from 0 to 100 points with higher scores representing increased activity and less pain. The VISA-A score is a validated questionnaire, specifically designed for evaluating outcome in Achilles tendinopathy. Previous formal studies on the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of the VISA-A score have varied between 6.5 and 16 points [27, 28]. Therefore, we considered an intermediate MCID of 12 points for our power calculation.

Secondary outcomes were tendon thickness, color Doppler activity, and other functional measures (such as pain and return to sports activity). Ultrasound findings in tendinopathy in general are characterized by increased tendon size [24]. Therefore, a tendon thickness decrease is considered a finding potentially representing improvement in the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy. Color Doppler activity of the Achilles tendon describes the degree of neovascularization. An increase in neovascularization has been observed within the first 3 weeks after applying sclerosing injections, which were successful when the neovascularization later disappeared after this initial period [2]. Although there is still discussion about the role of neovascularization, these findings suggest a beneficial effect of increased neovascularization within the very first period of treatment and an opposing effect when neovascularization is still present in the longer term [2], and so increase in color Doppler activity over time in our study is considered an indicator of a poorer result. The color Doppler activity was ranked in a new ranking scale from Grade 0 to 4. The grading was estimated in a 0.5-cm longitudinal part of the tendon with the maximal Doppler activity (region of interest): Grade 0 = no activity, Grade 1 = single vessel, Grade 2 = Doppler activity in < 25% of the region of interest, Grade 3 = Doppler activity in 25% to 50% of the region of interest, and Grade 4 = Doppler activity in > 50% of the region of interest [24, 33]. Pain at rest and pain while walking were assessed on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale, where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain imaginable [14]. The return to sports level was divided into five groups (not active in sports, no return to sports, returning to sport but not in desired sport, returning to desired sport but not at the preinjury level, and returning to preinjury level in the desired sport). We determined the patient’s return to desired sport regardless of the level [11].

Summary of Included Studies

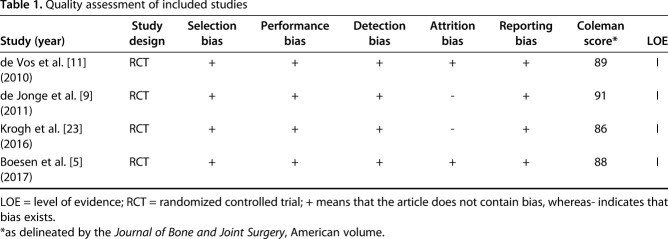

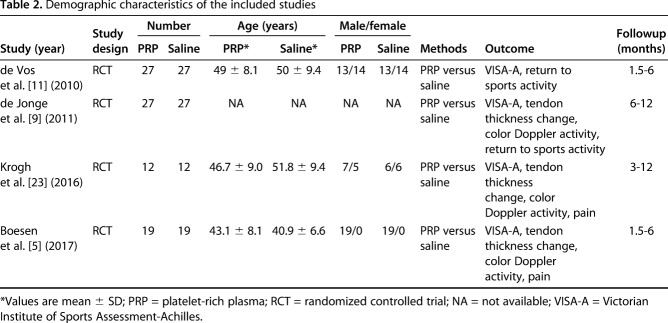

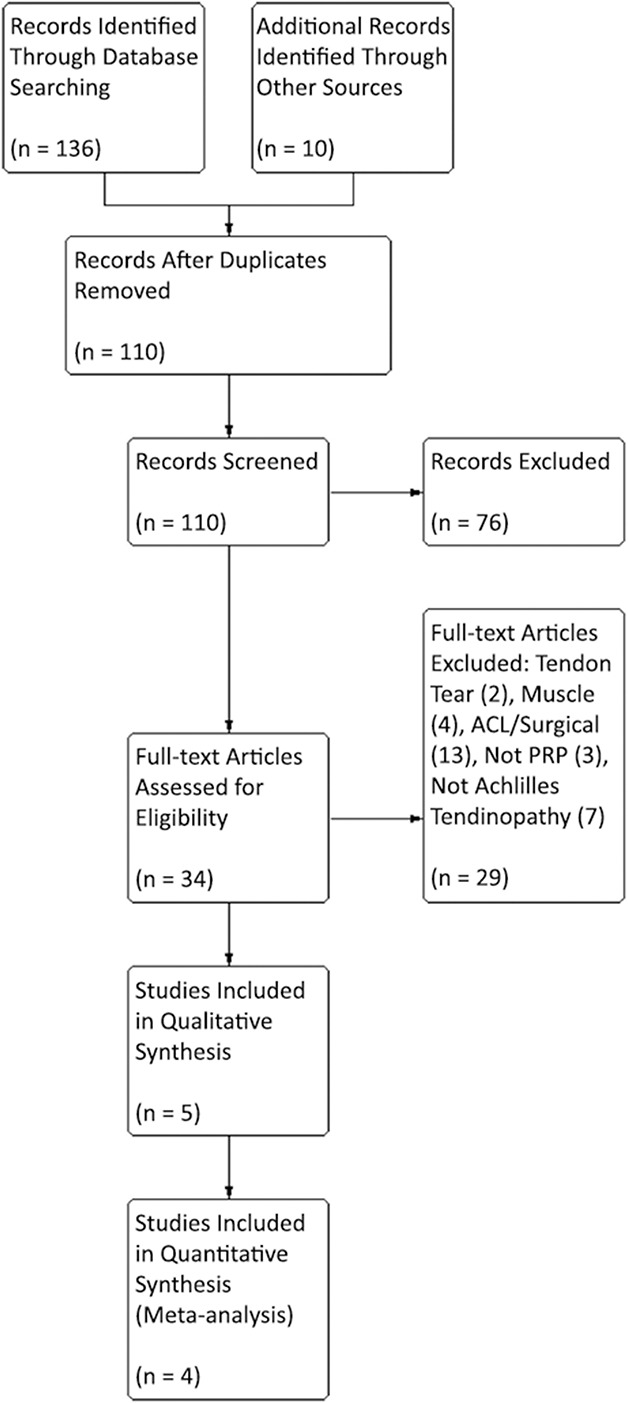

Of the 146 studies identified by our search, four studies [5, 9, 11, 23] were included in the qualitative synthesis. Studies were excluded if they related to tendon tears rather than tendinopathy, assessed muscle injuries, were duplicates, related to ligament injuries, had surgical interventions, or did not use PRP (Fig. 1). Studies were analyzed for control type as well as treatment type and technique. All trials compared PRP injection and eccentric training with saline injection and eccentric training for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. All trials evaluated VISA-A scores and three studies evaluated tendon thickness change and color Doppler activity for each group, but not all studies measured identical outcomes. The quality of the studies was determined on the risk of bias, including selection, performance, attrition, detection, reporting bias, and Coleman methodology score. All the included studies were Level I RCT studies with low risk of bias and high modified Coleman scores (> 80) (Table 1). A total number of 170 patients were enrolled in the meta-analysis, including 85 patients in the PRP group and 85 patients in the saline group. The mean age between these two groups was similar. However, there were fewer women than men in the study groups. The length of followup ranged from 3 to 12 months in the included studies. The detailed demographic characteristics of the four included studies are shown (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Flow of information through a systematic review for PRP in chronic Achilles tendinopathy is shown.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the included studies

Statistical Analysis

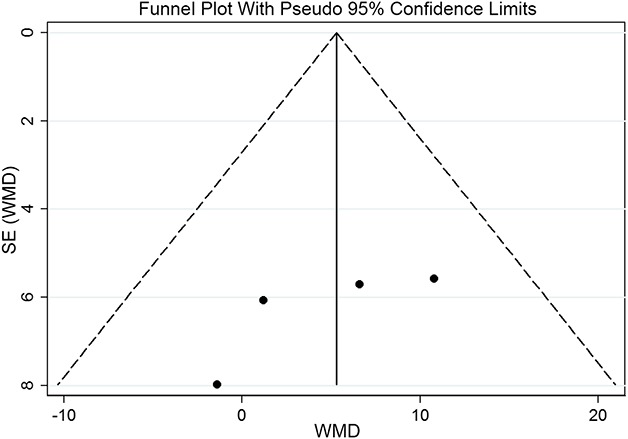

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 12 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables were analyzed using the weighted mean difference, and categorical variables were assessed using relative risks. In our study, p < 0.05 was statistically significant and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. The funnel plot and Egger’s test were performed for any publication bias of the pooling results on the VISA-A score in the meta-analysis. In this study, the results of the funnel plot suggested that no publication bias was present in results on the VISA-A score (Fig. 2), which was also statistically supported by Egger’s test (p = 0.222). Heterogeneity among trials was assessed using the I2 test statistic (0.50% is considered as having substantial heterogeneity). A random-effects model was used if the I2 value was statistically significant; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. In this meta-analysis, there was no heterogeneity in the VISA-A score (chi square = 2.18, p = 0.535, I2 = 0%) and a fixed-effects model was used. However, significant heterogeneity was found in tendon thickness change (chi square = 16.26, p < 0.001, I2 = 87.7%) and color Doppler activity (chi square = 13.62, p = 0.001, I2 = 85.3%), so a random-effects model was used.

Fig. 2.

The funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits of the VISA-A score suggested that there was no publication bias, which was also statistically supported by Egger’s test (p = 0.222). WMD = weighted mean difference.

Previous studies [27, 28] suggested that typical effect sizes might be in the range of 12 points on the VISA-A score. The SD of the VISA-A score was estimated at 15 points [12, 18, 31, 32]. For a two-sample pooled t-test of a normal mean difference with a two-sided significance level of 0.05, assuming a common SD of 15 VISA-A points, a sample size of 24 patients per group is required to obtain a power of at least 80% to detect a mean difference of 12 VISA-A points [11]. In this study, the pooling result of the VISA-A score showed a statistical power of 80.2% with the available 85 patients in each group.

Results

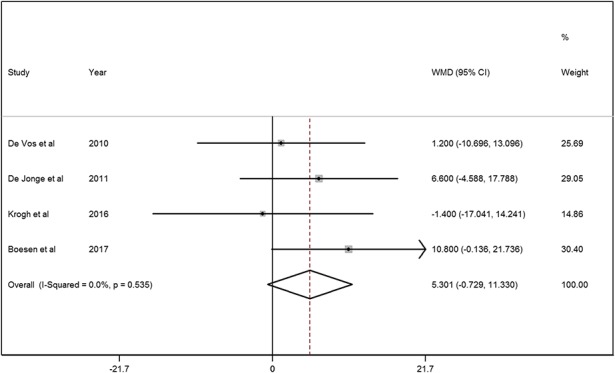

With the numbers available, there was no difference between the PRP and saline groups regarding the primary outcome (VISA-A score: mean difference [MD] = 5.3; 95% CI, -0.7 to 11.3; p = 0.085; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A forest plot showed the VISA-A scores in patients treated with PRP injection and saline injection. There was no heterogeneity in the VISA-A score (chi square = 2.18, p = 0.535, I2 = 0%) and a fixed-effects model was used. No significant difference between the PRP and saline groups was found on the VISA-A score (MD = 5.3, 95% CI, -0.7 to 11.3; z = 1.72, p = 0.085). The pooling result of the VISA-A score showed a statistical power of 80.2% with the available 85 patients in each group.

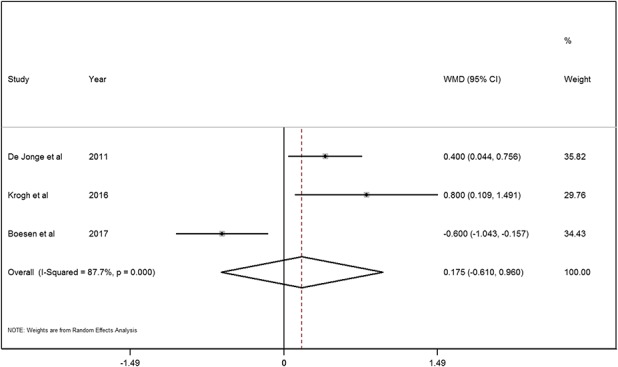

With the numbers available, we found no difference between the PRP and saline groups in terms of ultrasonographic evaluation of tendon thickness; the mean difference between the PRP and saline groups in tendon thickness change was 0.2 mm (95% CI, -0.6 to 1.0 mm; p = 0.663; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A forest plot showed the tendon thickness change in patients treated with PRP injection and saline injection. Significant heterogeneity was found in tendon thickness change (chi square = 16.26, p < 0.001, I2 = 87.7%) and a random-effects model was used. No significant difference between the PRP and saline groups was found on the tendon thickness change (MD = 0.2, 95% CI, -0.6 to 1.0; z = 0.44, p = 0.663).

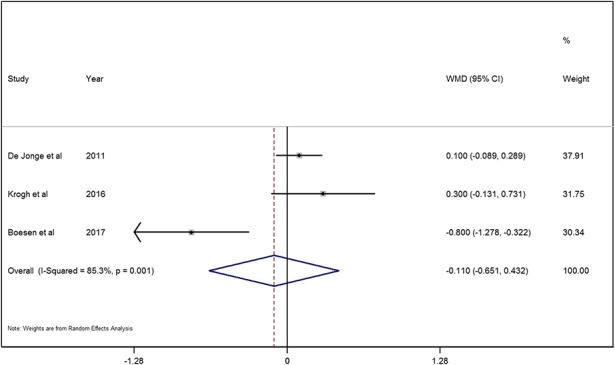

With the numbers available, we found no difference between the PRP and saline groups in terms of color Doppler activity (MD = 0.1; 95% CI, -0.7 to 0.4; p = 0.695; Fig. 5). Two studies [5, 23] evaluated tendon pain in the PRP and saline groups. Krogh et al. [23] reported that none of the three pain assessments (pain at rest, pain when walking, pain when the Achilles tendon was squeezed) demonstrated any difference between the PRP and saline groups at 3 months. The mean difference between PRP and saline groups for pain at rest was 1.6 (95% CI, -0.5 to 3.7; p = 0.137), pain when walking was 0.8 (95% CI, -1.8 to 3.3; p = 0.544), and pain when the Achilles tendon was squeezed was 0.3 (95% CI, -0.2 to 0.9; p = 0.208). However, Boesen et al. [5] reported that the decrease in visual analog scale scores was greater in the PRP group (37.1 ± 6.2 mm) when compared with the saline group (18.1 ± 6.0 mm) at 6 months followup (p < 0.05). de Vos et al. [11] reported that there was no difference in the number of patients returning to their desired sport (1.4%; 95% CI, −17.0% to 19.8%) between the PRP and saline groups (p > 0.05). In addition, de Jonge et al. [9] reached similar results in that there was no between-group difference in terms of return to sport with 15 patients returning to their previous sports in the PRP group compared with 11 in the saline group. The adjusted between-group difference for return to sports at 1-year followup was 1.8% (95% CI, -24.5 to 28.1; p = 0.894).

Fig. 5.

A forest plot showed the color Doppler activity in patients treated with PRP injection and saline injection. Significant heterogeneity was found in the color Doppler activity (chi square = 13.62, p = 0.001, I2 = 85.3%) and a random-effects model was used. No significant difference between the PRP and saline groups was found on the color Doppler activity (MD = -0.1, 95% CI, -0.7 to 0.4; z = 0.40, p = 0.695).

Discussion

Chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy is a very common disorder, and multiple treatment approaches have been recommended. However, best practices remain poorly defined. The application of PRP injection for Achilles tendinopathy has been reported by several high-quality studies [5, 9, 11, 13], but the results differed across those reports. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to try to reconcile those differences and provide some suggestions about the application of PRP in the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy. In this meta-analysis, we found that PRP injection for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy did not improve the VISA-A scores, increase the tendon structure, or alter the degree of Doppler activity compared with saline injection with the numbers available.

This study has several limitations. First, the total number of the sample size was small. Four RCT studies involving only 170 participants were eligible for inclusion with 85 participants in each group. However, our power calculation confirmed that we had 80% power to detect a 12-point difference on the VISA-A score, which is in the range of what others have found [12, 18, 32]. Formal studies on the MCID of the VISA-A score have varied between 6.5 and 16 points [27, 28]. We considered an intermediate MCID of 12 points for our power calculation, but if the smaller estimate of 6.5 is accurate, it is possible that a smaller but still clinically important benefit of treatment could exist and that a meta-analysis of the size we performed may not have had sufficient power to detect that benefit. Second, the studies considered included in this meta-analysis drew patients from the general population with few competitive elite athletes, and there were fewer women than men in the study groups. Those facts need to be considered when deciding how to generalize our findings. Third, the clinical heterogeneity of the included studies was high; to try to address this, we used a random-effects model in the analysis. Fourth, despite the funnel plot and Egger’s test demonstrating no statistical evidence of publication bias in the VISA-A scores, there might still be other factors inducing overestimating the benefits of PRP for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Fifth, the length of followup ranged from 3 to 12 months in the included studies, which is a relatively short period of surveillance. Although longer followup periods would have been desirable, it seems unlikely that benefits of PRP will be detected later if they were not present between 3 and 12 months after treatment.

In this meta-analysis of randomized trials, we found no benefit to PRP over saline injection with respect to VISA-A scores despite having adequate statistical power to detect a clinically important difference in the VISA-A score. We found one RCT [5] that reported four injections of PRP at 2-week intervals improved VISA-A scores for Achilles tendinopathy compared with saline injection. They surmised that repetition of injections may prolong the exposure of growth factors to the tendons and thereby improve the result [5]. However, before trials of repeated PRP injections should be considered, there needs to be convincing evidence that even a single course of treatment is beneficial. Our meta-analysis, which was limited to the best available evidence (Level I RCTs), found no such evidence. Until or unless that changes, we cannot recommend repeated courses of PRP as others have [5]; indeed, we cannot recommend PRP for general use until more robust evidence suggests it is beneficial.

In addition, we found no benefits to patients treated with PRP in terms of any secondary outcomes such as tendon thickness change, color Doppler activity, tendon pain, or return to sports activity. Three studies [5, 9, 23] evaluated tendon thickness change and color Doppler activity of Achilles tendon in both groups. These studies showed that tendon thickness decreased after PRP or saline injection with eccentric training, but they found no statistical difference between the PRP and saline groups at the last followup. Moreover, as far as the color Doppler activity, the results showed that PRP injection provided no statistical difference compared with saline injection in intratendinous vascularity for chronic Achilles tendon. Our meta-analysis therefore concluded that an injection of PRP for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendon did not increase the tendon structure or alter the degree of Doppler activity compared with saline injection. We note that two studies [5, 23] evaluated Achilles tendon pain and drew different conclusions; because of inconsistencies in reporting, we could not pool the data from these reports mathematically in our meta-analysis. Krogh et al. [23] saw no difference in favor of PRP compared with saline regarding tendon pain variation at 3 months followup. However, Boesen et al. [5] reported that tendon pain relief was greater in the PRP group when compared with the saline group both at 3 and 6 months followup. One explanation is that PRP contains many growth factors (including TGF-β, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and insulin-like growth factor 1), all of which have shown the potential to stimulate tendon healing [4, 19, 20, 29]. Moreover, Boesen et al. [5] surmised that repeated injections may prolong the exposure of growth factors to the tendons and thereby positively influence tendon rehabilitation compared with only one injection. Notwithstanding those two studies’ findings [5, 23], the evidence we were able to pool showed no apparent benefits to tendon healing after treatment with PRP.

Patients’ ability to return to their desired sport is an important factor to consider when determining suitable therapy. Inconsistencies in data reporting among the four studies did not allow for a direct or statistical comparison of patients returning to the desired sport in our meta-analysis. Two studies, de Vos et al. [11] and de Jonge et al. [9], compared the number of patients returning to their desired sport between the PRP and saline groups; with the numbers available, they found no differences in the likelihood that a patient would return to sport after treatment with PRP compared with saline [9, 11].

In conclusion, PRP injection with eccentric training did not improve VISA-A scores, reduce tendon thickness, or reduce color Doppler activity for chronic Achilles tendinopathy when compared with saline injection with eccentric training with sufficient statistical power analysis. However, our conclusions are based on only four RCTs with relatively small sample sizes. Larger randomized trials are needed to confirm these results, but until or unless a clear benefit has been demonstrated in favor of the new treatment, we cannot recommend it for general use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yang Lu for his contribution in constructing a search strategy for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Medical Science and Technology Funds (2017KY326; Y-JZ) and Zhejiang Provincial Basic Research for Public Welfare Funds (LGF18H060003; Y-JZ).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved for the reporting of this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Alfredson H, Lorentzon R. Chronic Achilles tendinosis: recommendations for treatment and prevention. Sports Med. 2000;29:135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Increased intratendinous vascularity in the early period after sclerosing injection treatment in Achilles tendinosis: a healing response? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfredson H, Pietilä T, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R. Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andia I, Sanchez M, Maffulli N. Tendon healing and platelet-rich plasma therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1415–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boesen AP, Hansen R, Boesen MI, Malliaras P, Langberg H. Effect of high-volume injection, platelet-rich plasma, and sham treatment in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized double-blinded prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:2034–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan O, O'Dowd D, Padhiar N, Morrissey D, King J, Jalan R, Maffulli N, Crisp T. High volume image guided injections in chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1697–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman BD, Khan KM, Maffulli N, Cook JL, Wark JD. Studies of surgical outcome after patellar tendinopathy: clinical significance of methodological deficiencies and guidelines for future studies. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vincenzo B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1751–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jonge S, de Vos RJ, Weir A, van Schie HT, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, Tol JL. One-year follow-up of platelet-rich plasma treatment in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1623–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jonge S, van den Berg C, de Vos RJ, van der Heide HJ, Weir A, Verhaar JA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Tol JL. Incidence of midportion Achilles tendinopathy in the general population. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:1026–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vos RJ, Weir A, van Schie HT, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, Tol JL. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vos RJ, Weir A, Visser RJ, de Winter T, Tol JL. The additional value of a night splint to eccentric exercises in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero G, Fabbro E, Orlandi D, Martini C, Lacelli F, Serafini G, Silvestri E, Sconfienza LM. Ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma in chronic Achilles and patellar tendinopathy. J Ultrasound. 2012;15:260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredberg U, Bolvig L, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Clemmensen D, Jakobsen BW, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Ultrasonography as a tool for diagnosis, guidance of local steroid injection and, together with pressure algometry, monitoring of the treatment of athletes with chronic jumper’s knee and Achilles tendinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen M, Boesen A, Holm L, Flyvbjerg A, Langberg H, Kjaer M. Local administration of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) stimulates tendon collagen synthesis in humans. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2013;23:614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org/. Updated September 2011. Accessed August 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.James SL, Ali K, Pocock C, Robertson C, Walter J, Bell J, Connell D. Ultrasound guided dry needling and autologous blood injection for patellar tendinosis. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong DU, Lee CR, Lee JH, Pak J, Kang LW, Jeong BC, Lee SH. Clinical applications of platelet-rich plasma in patellar tendinopathy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:249498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kampa RJ, Connell DA. Treatment of tendinopathy: is there a role for autologous whole blood and platelet rich plasma injection? Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1813–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjaer M, Langberg H, Heinemeier K, Bayer ML, Hansen M, Holm L, Doessing S, Kongsgaard M, Krogsgaard MR, Magnusson SP. From mechanical loading to collagen synthesis, structural changes and function in human tendon. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:500–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogh TP, Bartels EM, Ellingsen T, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Buchbinder R, Fredberg U, Bliddal H, Christensen R. Comparative effectiveness of injection therapies in lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1435–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh TP, Ellingsen T, Christensen R, Jensen P, Fredberg U. Ultrasound-guided injection therapy of Achilles tendinopathy with platelet-rich plasma or saline: a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1990–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Christensen R, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Ellingsen T. Ultrasonographic assessment of tendon thickness, Doppler activity and bony spurs of the elbow in patients with lateral epicondylitis and healthy subjects: a reliability and agreement study. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34:468–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loppini M, Maffulli N. Conservative management of tendinopathy: an evidence-based approach. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;1:134–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macdermid JC, Silbernagel KG. Outcome evaluation in tendinopathy: foundations of assessment and a summary of selected measures. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45:950–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormack J, Underwood F, Slaven E, Cappaert T. The minimum clinically important difference on the VISA-A and LEFS for patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:639–644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra A, Woodall J, Vieira A. Treatment of tendon and muscle using platelet-rich plasma. Clin Sports Med. 2009;28:113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olesen JL, Heinemeier KM, Langberg H, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M, Flyvbjerg A. Expression, content, and localization of insulin-like growth factor I in human Achilles tendon. Connect Tissue Res. 2006;47:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson JM, Cook JL, Purdam C, Visentini PJ, Ross J, Maffulli N, Taunton JE, Khan KM; Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. The VISA-A questionnaire: a valid and reliable index of the clinical severity of Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayana MK, Maffulli N. Eccentric calf muscle training in non-athletic patients with Achilles tendinopathy. J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunding K, Fahlstrom M, Werner S, Forssblad M, Willberg L. Evaluation of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy with greyscale ultrasound and colour Doppler: using a four-grade scale. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:1988–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA. 2015;313:1657–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Middelkoop M, Kolkman J, Van Ochten J, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Koes B. Prevalence and incidence of lower extremity injuries in male marathon runners. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]