Abstract

Background

In an era of increasing healthcare costs, the number and value of nonclinical workers, especially hospital management, has come under increased study. Compensation of hospital executives, especially at major nonprofit medical centers, and the “wage gap” with physicians and clinical staff has been highlighted in the national news. To our knowledge, a systematic analysis of this wage gap and its importance has not been investigated.

Questions/purposes

(1) How do wage trends compare between physicians and executives at major nonprofit medical centers? (2) What are the national trends in the wages and the number of nonclinical workers in the healthcare industry? (3) What do nonclinical workers contribute to the growth in national cost of healthcare wages? (4) How much do wages contribute to the growth of national healthcare costs? (5) What are the trends in healthcare utilization?

Methods

We identified chief executive officer (CEO) compensation and chief financial officer (CFO) compensation at 22 major US nonprofit medical centers, which were selected from the US News & World Report 2016-2017 Hospital Honor Roll list and four health systems with notable orthopaedic departments, using publicly available Internal Revenue Service 990 forms for the years 2005, 2010, and 2015. Trends in executive compensation over time were assessed using Pearson product-moment correlation tests. As institution-specific compensation data is not available, national mean compensation of orthopaedic surgeons, pediatricians, and registered nurses was used as a surrogate. We chose orthopaedic surgeons and pediatricians for analysis because they represent the two ends of the physician-compensation spectrum. US healthcare industry worker numbers and wages from 2005 to 2015 were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and used to calculate the national cost of healthcare wages. Healthcare utilization trends were assessed using data from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. All data were adjusted for inflation based on 2015 Consumer Price Index.

Results

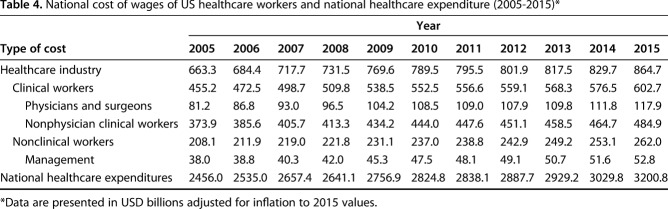

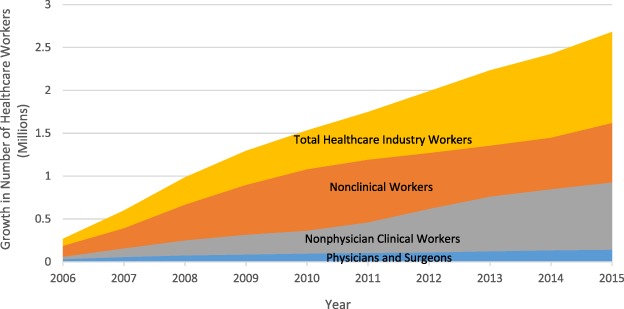

From 2005 to 2015, the mean major nonprofit medical center CEO compensation increased from USD 1.6 ± 0.9 million to USD 3.1 ± 1.7 million, or a 93% increase (R2 = 0.112; p = 0.009). The wage gap increased from 3:1 to 5:1 with orthopaedic surgeons, from 7:1 to 12:1 with pediatricians, and from 23:1 to 44:1 with registered nurses. We saw a similar wage-gap trend in CFO compensation. From 2005 to 2015, mean healthcare worker wages increased 8%. Management worker wages increased 14%, nonclinical worker wages increased 7%, and physician salaries increased 10%. The number of healthcare workers rose 20%, from 13 million to 15 million. Management workers accounted for 3% of this growth, nonclinical workers accounted for 27%, and physicians accounted for 5% of the growth. From 2005 to 2015, the national cost-burden of healthcare worker wages grew from USD 663 billion to USD 865 billion (a 30% increase). Nonclinical workers accounted for 27% of this growth, management workers accounted for 7%, and physicians accounted for 18%. In 2015, there were 10 nonclinical workers for every one physician. The cost of healthcare worker wages accounted for 27% of the growth in national healthcare expenditures. From 2005 to 2015, the number of inpatient stays decreased from 38 million to 36 million (a 5% decrease), the number of physician office visits increased from 964 million to 991 million (a 3% increase), and the number of emergency department visits increased from 115 million to 137 million (a 19% increase).

Conclusions

There is a fast-rising wage gap between the top executives of major nonprofit centers and physicians that reflects the substantial, and growing, cost of nonclinical worker wages to the US healthcare system. However, there does not appear to be a proportionate increase in healthcare utilization. These findings suggest a growing, substantial burden of nonclinical tasks in healthcare. Methods to reduce nonclinical work in healthcare may result in important cost-savings.

Level of Evidence Level

IV, economic and decision analysis.

Introduction

The cost of health care in the United States is a controversial issue. Currently, healthcare costs exceed 17% of the gross domestic product, and they are projected to continue rising [5, 24]. The costs associated with healthcare administration contribute substantially to the cost of health care and are a topic of increasing study [3, 13, 32, 33]. More recently, the compensation of hospital management workers, especially at major nonprofit medical centers, has come under the public spotlight. For example, the Boston Globe recently reported that the Partners Healthcare chief executive officer (CEO) earned USD 4.3 million in total compensation in 2015, a threefold increase over the prior year. Several studies have documented that the compensation of hospital management frequently exceeds that of most physicians [12, 27]. To the authors’ knowledge, a systematic analysis of the trends in wage gaps between management and physicians at major nonprofit institutions has not been performed, and it is unknown if these findings reflect national trends.

Administrative costs in the US healthcare industry are substantial, accounting for 25% of hospital expenditures in 2011, and they are higher than peer nations without translating into higher quality care [13, 25, 32]. Administrative and clerical workers comprised 18% of the healthcare workforce in 1969; that number reached 27% in 1999 [32]. Kocher et al. [17] reported that, in 2013, 10 of 16 nonphysician healthcare workers did not have clinical roles (such as administrative staff, receptionists, and clerks). Growth in both the number of workers and wages contributes to the national cost-burden of wages and may partially explain rising healthcare costs [17]. The relative contributions of nonclinical healthcare workers, specifically management workers, to the growth in national cost-burden of wages has not been explored.

We therefore asked: (1) How do wage trends compare between physicians and executives at major nonprofit medical centers? (2) What are the national trends in wages and the number of nonclinical workers in the healthcare industry? (3) What do nonclinical workers contribute to the growth in national cost of healthcare wages? (4) How much do wages contribute to the growth of national healthcare costs? (5) What are the trends in healthcare utilization?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

Institutional Review Board approval was not obtained because all data were publicly accessible. This is a retrospective, descriptive study of the US healthcare system from 2005 to 2015. We compared the wage gap between nonprofit hospital administrators and physicians and registered nurses for the years 2005, 2010, and 2015 using publicly available data, including Internal Revenue Service 990 forms and public university websites. We identified trends in national healthcare worker numbers and wages using Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2005 to 2015, and we compared them based on occupation. Healthcare worker numbers and mean wages were used to calculate the national cost of healthcare wages from 2005 to 2015 and compared based on occupation. We obtained the data on national healthcare expenditures from 2005 to 2015 from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Participants/Study Subjects

Nonprofit Hospital Executive and Physician Participants

We collected hospital executive wages from four sources of publicly available data: (1) Form 990 data from GuideStar (https://www.guidestar.org), (2) Form 990 data from Nonprofit Explorer by ProPublica (https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits), (3) Compensation at the University of California (https://ucannualwage.ucop.edu/wage), (4) Compensation at the University of Michigan (https://hr.umich.edu/working-u-m/management-administration/records-management-data-services/hr-data-reports). Wage data was collected for the CEO and chief financial officer (CFO) of 22 major nonprofit healthcare systems in 2005, 2010, and 2015 (Table 1). We used the US News & World Report 2016-2017 Hospital Honor Roll list and four nonprofit medical centers with notable orthopaedics departments in our analysis, consisting of three top 10 US News & World Report orthopedic hospitals not in the honor roll and our own institution [29]. One healthcare system (University of Colorado) on the Honor Roll did not have accessible data, and Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital were assessed using the combined Partners healthcare system.

Table 1.

Nonprofit healthcare organizations included for analysis

As there was no specific institutional data on physicians, we used national compensation data as a surrogate. We compared the wages of orthopaedic surgeons and pediatricians, which reflect two ends of the physician compensation spectrum [9], and registered nurses, which comprise a large proportion of clinical staff, with the wages of hospital executives. To obtain wage data for orthopaedic surgeons and pediatricians, we visited the American Medical Group Association website (www.amga.org), which surveyed several hundred academic and private-practice US physicians in each specialty. Academic physician salaries are on average 13% lower than nonacademic salaries [7]. For wage data on registered nurses, we visited the Bureau of Labor Statistics website (www.bls.gov), which provides mean wages for all US registered nurses.

National Healthcare Worker Numbers, Wages, and Expenditure

We used the Bureau of Labor Statistics public datasets to acquire national wage and worker data from 2005 to 2015 (www.bls.gov). Healthcare industry workers were identified based on worker group: physicians, nonphysician clinical workers (workers who were not physicians who directly interact with patients, ie, nurses and phlebotomists), or nonclinical workers (workers who do not interact with patients, ie, management and clerks). Management and chief executive workers, which comprise a subset of nonclinical workers, were further analyzed.

We obtained data on national healthcare expenditures from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (www.cms.gov).

National Healthcare Utilization Trends

We assessed healthcare utilization trends from 2005 to 2015 using three US government datasets. We assessed the number of inpatient stays using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov). We assessed the number of outpatient physician office visits using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm). We assessed number of emergency department visits using the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm).

Comparisons

We retrospectively assessed and qualitatively compared the wages of nonprofit hospital executives, orthopaedic surgeons, pediatricians, and registered nurses in 2005, 2010, and 2015. In addition, we retrospectively assessed the number and mean wages of US healthcare workers in that same period. Growth rates in mean wages were compared qualitatively based on worker group (physicians, nonphysician clinical workers, and nonclinical workers, with a subanalysis of management workers). Relative contributions of each worker group to the growth in the number of healthcare workers from 2005 to 2015 were also compared qualitatively.

Using the number of healthcare workers and their mean wages, we made annual calculations of the national cost of healthcare wages from 2005 to 2015. We qualitatively compared the relative contribution of each worker group to the growth in national cost of healthcare wages. The relative contribution of the growth in cost of healthcare wages to the growth in national healthcare expenditure was assessed.

Variables, Outcome Measures, Data Sources, and Bias

We calculated the mean wage of the 22 nonprofit hospital CEOs and CFOs (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1). The total wage (base salary, bonus, and other sources of income as available) was used in this study. Mean wages were reported for orthopaedic surgeons, pediatricians, and registered nurses (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

A mean of 1.68 tax-ID numbers per healthcare system were used to obtain hospital administrator compensations, excluding the three public university healthcare systems (the University of California Los Angeles, the University of California San Francisco, and the University of Michigan). In terms of CEO data, we obtained compensation data for 77% of CEOs in 2005, 95% of CEOs in 2010, and 100% in 2015. In terms of CFO data, we obtained compensation for 77% of CFOs in 2005, 100% in 2010, and 95% in 2015.

We used the Bureau of Labor Statistics industry-specific datasets in this study. The healthcare industry was defined as a composite of ambulatory healthcare services, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities industries, as identified by North America Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes 621000, 622000, and 623000 respectively [31]. We excluded social assistance, NAICS code 624000, and insurance industries, NAICS code 524000 from our analysis.

We assessed three broad healthcare worker groups—physicians, nonphysician clinical workers, and nonclinical workers—based on occupational data from the ambulatory healthcare services, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities industries using Standard Occupational Classification codes [30]. The number of workers and mean wages for all workers (code 00-0000) and subsets of management (code 11-0000), chief executives (11-1011), healthcare practitioners (29-0000), and healthcare support (31-0000) were identified. Physicians were identified based on the physician and surgeon occupation code (29-1060). Physician worker number and mean wage data were available directly from 2012 to 2015 datasets and calculated using available specialty fields from 2005 to 2011 datasets. Nonphysician clinical workers were defined as a summation of healthcare practitioner and healthcare support occupations excluding physicians. Nonclinical workers included all workers not in healthcare practitioner or healthcare support occupations.

Healthcare industry mean wages for each worker group were calculated based on a weighted average wage for each worker group in the ambulatory healthcare services, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities industries. Healthcare industry worker numbers for each worker group were calculated based on the sum of the number of workers for each worker group in the ambulatory healthcare services, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities industries.

We calculated the national cost of healthcare wages based on the mean wages and the number of worker figures for the overall healthcare industry and for each worker group from 2005 to 2015.There are several potential sources of bias in this study. We compared site-specific CEO and CFO data to national average salary data of orthopaedic surgeons, pediatricians, and registered nurses. IRS 990 forms only contain salary data for their highest compensated employees, therefore institution-specific data on physician and nurse wages were not available. There is a degree of incomplete data in the CEO and CFO salary data, especially in the 2005 timepoints, which may bias the results. CEO and CFO salary data were normally distributed in 2005 and 2015 timepoints, but not in 2010, which may also affect our analysis on salary growth. The executive compensation at the healthcare systems chosen in this study may not be representative of all hospitals nationally. Finally, we chose two physician specialties that represent a range of average physician compensation. However, these specialties may not be representative of the trend of the average physician-executive wage gap.

Statistical Analysis, Study Size

Shapiro-Wilk tests identified CEO and CFO data in 2005 (p = 0.078, p = 0.220 respectively) and 2015 (p = 0.480, p = 0.394 respectively) were normally distributed, while 2010 data were not normally distributed (p = 0.002, p = 0.022 respectively). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. We performed Pearson correlation to assess the trend between hospital administrator compensation and time. An alpha value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Demographics, Description of Study Population

All wages are presented in USD. All monetary values were adjusted for inflation to 2015 USD using the Consumer Price Index (CPI-U, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/).

Results

Physician and Executive Wage Trends at Major Nonprofit Medical Centers

Inflation-adjusted CEO compensation increased, with mean compensation at USD 1.6 million ± 0.9 million in 2005, USD 2.9 million ± 2.0 million in 2010, and USD 3.1 million ± 1.7 million in 2015 (a 93% increase; R2 = 0.112; p = 0.009). In addition, CFO compensation increased, with mean compensation at USD 740,000 ± 289,000 in 2005, USD 1.3 million ± 0.7 million in 2010, and USD 1.4 million ± 0.5 million in 2015 (an 83% increase; R2=0.156; p = 0.002).

Inflation-adjusted orthopaedic surgeon compensation increased from USD 491,000 ± 162,000 in 2005, to USD 596,000 ± 267,000 in 2010, to USD 617,000 ± 279,000 in 2015 (26% increase). Pediatrician compensation increased from USD 223,000 ± 79,000 2005, to USD 249,000 ± 93,000 in 2010, to 256,000 ± 99,000 in 2015 (15% increase). Registered nurse compensation increased from USD 69,000 in 2005, to USD 74,000 in 2010, and decreased to USD 71,000 in 2015 (overall 3% increase).

The wage gap between hospital CEOs and orthopaedic surgeons increased from 3:1 in 2005 to 5:1 in 2015 (Fig. 1). The wage gap between hospital CFOs and orthopaedic surgeons increased from 1.5:1 in 2005 to 2.2:1 in 2015 (Fig. 1). The wage gap between hospital executives and pediatricians and registered nurses increased at an even greater rate. The wage gap between hospital CEOs and pediatricians increased from 7:1 in 2005 to 12:1 in 2015. The wage gap between hospital CEOs and registered nurses increased from 23:1 in 2005 to 44:1 in 2015. The wage gap between hospital CFOs and pediatricians increased from 3:1 in 2005 to 5:1 in 2015. The wage gap between CFOs and registered nurses increased from 11:1 in 2005 to 19:1 in 2015.

Fig. 1.

From 2005 to 2015, there is a trend towards increasing wage gaps between hospital chief executive officers (CEOs) and clinical workers at 22 major nonprofit medical centers. A similar increasing wage gap is observed between hospital chief financial officers (CFOs) and clinical workers.

What Are The National Trends in Wages and the Number of Nonclinical Workers in the Healthcare Industry?

During the study period, we observed an increase in healthcare wages. From 2005 to 2015, overall mean wages of healthcare industry workers increased 8% from USD 50,435 to USD 54,618 (Table 2). The mean salaries of nonclinical workers increased 7% from USD 39,094 to USD 41,927. The mean salaries of healthcare chief executives increased 11%, from USD 162,004 to USD 179,785, and the mean salaries of healthcare management workers increased 14%, from USD 93,202 to USD 105,801. Average physician salaries increased 10%, from USD 187,895 to USD 206,242, and the mean salaries of nonphysician clinical workers increased 6%, from USD 50,563 to USD 53,803.

Table 2.

Wages of US healthcare industry workers (2005-2015)*

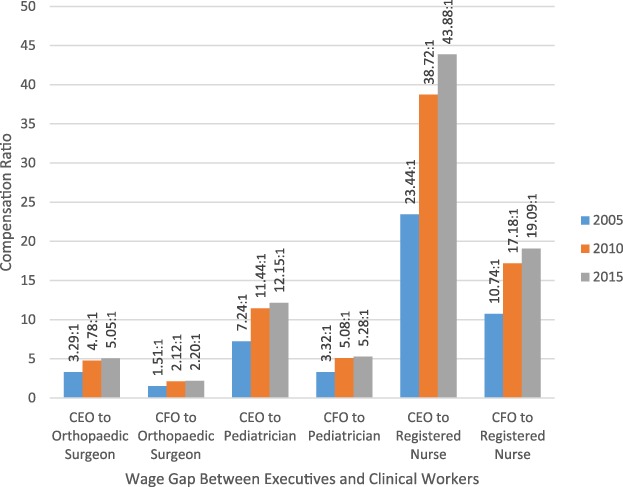

There was substantial growth in the number of US healthcare workers during the study period. From 2005 to 2015, the number of healthcare industry workers grew 20%, from 13 million to 15 million workers (Table 3). Physicians accounted for 5% of this growth (Fig. 2). Nonclinical workers accounted for 35% of this growth, and management workers specifically contributed 3%. Nonphysician clinical workers contributed the remaining 60% of the growth of healthcare industry workers.

Table 3.

Number of employees in the US healthcare industry (2005-2015)

Fig. 2.

Since 2005, there have been more than 2.5 million additional workers added to the healthcare field (more than 20% growth). Physicians accounted for 5% of this growth, nonclinical workers accounted for 35% of this growth, and nonphysician clinical workers contributed the remaining 60% of the growth.

What do Nonclinical Workers Contribute to the Growth in National Cost of Healthcare Wages?

In our study, nonclinical workers were a primary driver of the growth of national cost of health care wages. From 2005 to 2015, the national costs of healthcare wages grew 30%, from USD 663 billion to USD 865 billion (Fig. 3). Physicians contributed 18% to the growth in national cost of healthcare wages (a USD 37 billion increase; Table 4). Nonclinical workers contributed 27% to growth (a USD 53 billion increase), and management workers specifically contributed 7% (a USD 15 billion increase). Nonphysician clinical workers contributed the remaining 55% of growth. In 2015, for every physician, there was one management worker, 10 nonclinical workers, and 14 nonphysician clinical workers.

Fig. 3.

Since 2005, the cost of wages of healthcare workers increased by USD 200 billion (a 30% increase). Physicians contributed 18% to the growth in national cost of healthcare wages. Nonclinical workers contributed 27% to growth. Nonphysician clinical workers contributed the remaining 55% of growth. All data were adjusted for inflation based on 2015 Consumer Price Index.

Table 4.

National cost of wages of US healthcare workers and national healthcare expenditure (2005-2015)*

How Much do Wages Contribute to the Growth of National Healthcare Costs?

The national cost of healthcare wages contributed a substantial portion of the yearly national healthcare expenditure and its growth. From 2005 to 2015, the cost of wages on average comprised 28% of the national healthcare expenditure (Table 4). From 2005 to 2015, the national healthcare expenditure grew 30%, from USD 2.5 trillion to USD 3.2 trillion. The national cost of healthcare wages accounted for 27% of this growth (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Since 2005, the national healthcare expenditure grew more than USD 700 billion (a 30% increase). The national cost of healthcare wages accounted for 27% of this growth. All data were adjusted for inflation based on 2015 Consumer Price Index.

What are the Trends in Healthcare Utilization?

From 2005 to 2015, the number of inpatient stays decreased 5% from 38 million to 36 million, the number of physician office visits increased 3% from 964 million to 991 million, and the number of emergency department visits increased 19% from 115 million to 137 million (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

From 2005 to 2015, the number of inpatient stays decreased from 38 million to 36 million (a 5% decrease), the number of physician office visits increased from 964 million to 991 million (a 3% increase), and the number of emergency department visits increased from 115 million to 137 million (a 19% increase).

Discussion

Management workers and nonclinical staff are essential for the function of a complex modern healthcare system. Executives and managerial staff justify their wage growth through activities such as improving efficiency or quality of care [26]. With healthcare costs projected to continue increasing, the value of nonclinical staff, and especially CEOs, has come under increased scrutiny [5]. National news outlets have anecdotally used the compensation of CEOs at several major nonprofit medical centers to call to attention the cost of healthcare management and administrative workers [12, 21]. We assessed the compensation of CEOs and CFOs at 22 major nonprofit medical centers from 2005 to 2015 and found an increasing wage gap with physicians and registered nurses. These trends in major nonprofit hospitals were reflected nationally, where it was found that growth in wages and the number of management and nonclinical healthcare workers contributed substantially to the growing healthcare cost-burden. While our study cannot comment on the value of nonclinical workers, the growth in costs appears to outpace plausible growth in value, given the relative stagnation of healthcare utilization during the 10-year period of our study. It appears unlikely to us that the near-doubling of mean compensation to hospital executives is justified by the value added by their work.

Limitations

There are several caveats to this study. We did not account for healthcare insurance workers, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics database classified insurance workers as a separate industry. Therefore, this study may have underestimated both the cost-burden and the growth in the number of nonclinical healthcare workers. This study may have also underestimated the compensation of healthcare executives, as publicly available 990 forms and Bureau of Labor Statistics data have not been extensively validated and may not fully capture indirect compensation, such as enhanced benefits. Additionally, the publicly available salary data from UCLA, UCSF, and University of Michigan only provide base salary data and do not report bonuses or other benefits, which may further underestimate executive compensation. This study may have also overestimated the wages of orthopaedic surgeons and pediatricians that were compared with executive wages because national mean wages that were used in this study have private practice representation [7]. We may have underestimated total healthcare utilization. We assessed healthcare utilization in three major areas: inpatient stays, physician clinic visits, and emergency department visits; however, our assessment was not comprehensive, and areas such as nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and dentistry visits were not assessed. We also did not assess trends in healthcare quality metrics, which may be the area in which nonclinical workers create value. Finally, we did not analyze factors associated with either executive or physician compensation. A study analyzing trends in such metrics as hospital acquisitions, number of hospital beds, quality metrics, and financial metrics may offer insight into factors associated with executive compensation. Further study into trends of productivity of physicians should also be performed.

Physician and Executive Wage Trends at Major Nonprofit Medical Centers

In the wake of the financial crisis of the late 2000s, the United States passed the Dodd-Frank Act to improve financial regulation [19]. As part of this act, employee pay and the pay gap with executives were disclosed at major US businesses, demonstrating pay ratios of several magnitudes of difference at these businesses [11]. Prior studies have also showed an increasing wage gap between CEOs and workers in publicly traded companies [22]. Our study shows that these compensation trends were paralleled in major nonprofit medical centers and the national healthcare industry in general. Justification of executive salary wage growth has been difficult to find [10, 12, 23]. CEO compensation has not been associated with productivity metrics in either the public sector or the healthcare industry [16, 22]. Mishel et al. [22] noted a decrease in CEO compensation of publicly traded companies in 2009 following the 2008 financial crisis, from USD 18.8 million to USD 10.6 million, which recovered to USD 16.3 million by 2014. Studies on the trends of hospital executive salaries with changes in financial metrics, quality metrics, and mergers/acquisitions, should be performed.

Healthcare chief executive compensation was not affected by the financial crisis. In fact, wages grew consistently in the years immediately after the crisis (Table 2), despite the vulnerability of the healthcare industry to its consequences, such as rising unemployment, decreasing health insurance coverage, decreasing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, and decreasing availability of capital and credit [1]. Furthermore, a report from the American Hospital Association showed that the 2008 financial crisis had an important impact on hospitals’ total margins [2]; however, by 2010, hospitals had recovered financially. Whether hospital executives were responsible for this robust recovery or simply benefited from it is difficult to answer. One possible reason for the robust growth of hospital executive compensation is that, unlike for-profit, publicly traded companies, where administrators have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize shareholder value and a free-market determines the value of business decisions made, hospital administrators answer only to the hospital’s voluntary board of directors and its respective stakeholders [4]. It is common practice for nonprofit hospital boards, through hospital human resource departments, to annually contract independent administrator compensation consulting groups to rationalize the fair market value compensation of high-level hospital administrators. However, there are conflicting incentives for consultants to recommend compensation increases for these hospital administrators as this will incentivize subsequent renewal of the consulting engagement.

Trends in Wages and Number of Nonclinical Workers, and Comparison to Healthcare Utilization

We found that a substantial portion of the growth in the cost-burden of healthcare worker wages stemmed from management and nonclinical workers. Both increasing wages, as discussed previously, and an increasing number of these workers contributed to this cost. In 2015, physicians comprised one of every 25 workers. For every one physician, there was one management worker and 10 nonclinical workers. Compared with the growth in wages (7% increase from 2005 to 2015), the growth in the number of nonclinical workers (a 17% increase from 2005 to 2015) may have contributed more to this cost-burden. Therefore, the value of every nonclinical healthcare worker should be evaluated. Hospitals with more administrative staff should develop greater improvements in efficiency and quality of care. However, several analyses on for-profit hospitals, which have relatively higher administrative costs, did not find improved care or reduced costs when compared with nonprofit hospitals [8, 14, 15, 28]. Labor productivity in the healthcare industry has also decreased by 0.6% [18]. Although the total number of healthcare workers grew 20% from 2005 to 2015, physicians comprised only 5% of that growth. In comparison, nonclinical workers comprised 35% of the growth, which is seven times that of physicians. Furthermore, we found that healthcare utilization remained relatively stagnant over the last decade, with the number of inpatient and physician office visits showing little change. Although emergency department visits grew 18%, the absolute increase number of visits (22 million) is relatively small. These findings suggest the substantial, growing nonclinical side of healthcare, resulting in important wage costs from nonclinical healthcare workers. Methods to improve efficiency and productivity in healthcare should be pursued [17]. Furthermore, efforts should be made to align incentives and decrease administrative complexity to improve productivity and reduce costs associated with nonrevenue-generating healthcare workers [6, 17, 18, 20].

Conclusions

There is a fast-rising wage gap between the top executives of major nonprofit centers and physicians that reflects the substantial, and growing, cost-burden of management and nonclinical worker wages on the US healthcare system. However, there does not appear to be a substantial increase in healthcare utilization. These findings suggest a growing, serious burden of nonclinical tasks in health care. Further research and efforts should be made to improve efficiency and productivity in health care.

Footnotes

One of the authors (JYD) has received, during the study period, internal institutional funding from the Dudley P. Allen Fellowship. One of the authors (REM) certifies that he is a board member of the Association of Bone and Joint Surgeons, an editorial board member of Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, and on the medical advisory board for the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and has received or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of under USD 20,000.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his institution waived approval for the reporting of this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.American Hospital Association. Trendwatch: The economic downturn and its impact on hospitals. Available at: https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2009-01-14-trendwatch-economic-downturn-and-its-impact-hospitals. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 2.American Hospital Association. Trendwatch Chartbook 2016: trends affecting hospitals and health systems. Available at: https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2017-12-11-trendwatch-chartbook. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 3.Blumenthal D. Administrative issues in health care reform. New Engl J Med. 1993;329:428–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brickley JA, Simon W E, Van Horn L, Wedig GJ. Board structure and executive compensation in nonprofit organizations: evidence from hospitals. J Econ Behav Organ. 2010;76:196–208. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National healthcare expenditure data: projected. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.html. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 6.Cutler D, Wikler E, Basch P. Reducing administrative costs and improving the health care system. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:1875–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis J. We analyzed 35,000 physician salaries. Here's what we found.Available at: https://blog.doximity.com/articles/we-analyzed-35-000-physician-salaries-here-s-what-we-found. Accessed March 31, 2018.

- 8.Devereaux PJ, Choi PTL, Lacchetti C, Weaver B, Schunemann HJ, Haines T, Lavis JN, Grant BJB, Haslam DRS, Bhandari M, Sullivan T, Cook DJ, Walter SD, Meade M, Khan H, Bhatnager N, Guyatt GH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166:1399–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doximity. Doximity 2018 physician compensation report. Available at: https://blog.doximity.com/articles/doximity-2018-physician-compensation-report. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 10.Edmans A. Why We Need to Stop Obsessing Over CEO Pay Ratios. Harvard Business Review. February 23, 2017. Available at: https://hbr.org/2017/02/why-we-need-to-stop-obsessing-over-ceo-pay-ratios. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 11.Francis T, Fuhrmans V. Are you underpaid? In a first, U.S. firms reveal how much they pay workers. The Wall Street Journal. March 12, 2018. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/are-you-underpaid-in-a-first-u-s-firms-reveal-how-much-they-pay-workers-1520766000. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 12.Gunderman R. Why are hospital CEOs paid so well? The Atlantic. October 16, 2013. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/10/why-are-hospital-ceos-paid-so-well/280604/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 13.Himmelstein DU, Jun M, Busse R, Chevreul K, Geissler A, Jeurissen P, Thomson S, Vinet MA, Woolhandler S. A comparison of hospital administrative costs in eight nations: US costs exceed all others by far. Health Affairs. 2014;33:1586–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Taking care of business: HMOs that spend more on administration deliver lower-quality care. Int J Healthc Manag. 2002;32:657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Hellander I, Wolfe SM. Quality of care in investor-owned vs not-for-profit HMOs. JAMA. 1999;282:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joynt KE, Le ST, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Compensation of chief executive officers at nonprofit US hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocher R. The downside of health care job growth. Harvard Business Review. September 23, 2013. Available at: https://hbr.org/2013/09/the-downside-of-health-care-job-growth. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 18.Kocher R, Sahni NR. Rethinking health care labor. New Engl J Med. 2011;365:1370–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Library of Congress. H.R.4173-Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

- 20.Marcus RE, Zenty TF, 3rd, Adelman HG. Aligning incentives in orthopaedics: opportunities and challenges – the Case Medical Center experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2525–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCluskey P. Partners CEO tops hospital pay list. The Boston Globe. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2017/08/15/partners-ceo-tops-hospital-pay-list/80PxEI23H2S7mITnBKRMAJ/story.html. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 22.Mishel L, Davis A. Top CEOs make 300 times more than typical workers. 2005. Economic Policy Institute. Available at: http://www.epi.org/publication/top-ceos-make-300-times-more-than-workers-pay-growth-surpasses-market-gains-and-the-rest-of-the-0-1-percent/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 23.Mishra CS, McConaughy DL, Gobeli DH. Effectiveness of CEO pay-for-performance. Review of Financial Economics. 2000;9:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moses H, Matheson DH, Dorsey ER, George BP, Sadoff D, Yoshimura S. The anatomy of health care in the United States. JAMA. 2013;310:1947–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health Care Quality Indicators. Available at: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT#. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 26.Porter ME. What is value in health care? New Engl J Med. 2010;363:2477–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenthal E. Medicine's Top Earners are not the M.D.s. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/18/sunday-review/doctors-salaries-are-not-the-big-cost.html. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 28.Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM. Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit health plans enrolling Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2005;118:1392–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Standard Occupational Classification. United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/soc/2010/home.htm. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- 30.United States Census Bureau. North American Industry Classification System. United States Census Bureau. Available at: https://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/. Accessed April 28, 2018.

- 31.US News & World Report. 2016-17 Best Hospitals Honor Roll. August 2, 2017. Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/us-news–world-report-announces-2016-17-best-hospitals-300307279.html. Accessed March 1, 2018.

- 32.Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU. Costs of health care administration in the United States and Canada. New Engl J Med. 2003;349:768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU. Health care administration in the United States and Canada: micromanagement, macro costs. Int J Health Serv. 2004;34:65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]