“[T]his story has to be told and retold to honor those who were victims. Their heroic deeds should not be lost in history but must be irremovably secured in it” — Edzard Ernst MD, PhD, Emeritus Professor, Exeter University [6].

Is it possible that we are losing the horrors of the Holocaust to history as Dr. Ernst feared? A recent survey found that adults, particularly those between 18-34 years of age, do not know basic facts about the Holocaust. According to the survey, 41% of Americans, and 66% of millennials do not know the historical significance of Auschwitz [1]. Despite state-conducted human rights violations persisting to the present day—including the use of poison gas on civilians [2]—and despite the year 2018 being the 70th anniversary of the execution of a number of Nazi physicians following the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial, it is my perception that the criminal trespasses of members of our own profession during World War II are unknown to many young physicians and surgeons.

For this reason, I spent 3 years in local and national archives in Germany, reviewing tens of thousands of pages of original documents, which are the primary source of evidence we have about the experiments covered in the Doctors’ Trial of 20 physicians that concluded in 1947 [4]. While the justice was at best incomplete, the trial (officially titled United States of America v Karl Brandt, et al, but known as the Doctors’ Trial) also served as the origin of the Nuremberg code, which defined the principles of human-subjects in the modern era. Because the connection between those dreadful events and the principles that arose from the trials that followed is only loosely made in the minds of young physicians some four generations later, I want to render those events explicitly here, for an orthopaedic audience. What kinds of experiments did our professional forbears—all educated, orthopaedic and trauma surgeons—perform on innocent victims [20] and how did they attempt to justify their heinous, criminal behaviors?

In this essay, the first of a two-part series, I used the original trial documents [3] to provide a realistic sense of the Nazi orthopaedic experiments; quotations in my essay were taken directly from the case files. To my knowledge, this is the first primary-source driven rendering of these experiments to be published in an orthopaedic journal.

It is worth noting that the heinous experiments at Ravensbrück concentration camp and elsewhere I will describe did not arise in a vacuum; rather, medicine was a crucial—and in some instances, an intentionally lethal—tool of the Nazi regime’s racial and social policies [11, 19]. In fact, one study found that 27,759 people were victims of the experiments and 4364 died due to the experiments or were killed after the experiments [20]. Institutionalization of criminal conduct in the name of public health and “racial hygiene” was a Nazi priority, since they asserted that superior people (the “Aryan race”) had the right to dominate and exterminate supposed inferior elements, including Jews, Slavs, the Roma, Africans, and Asians. Although around six million Jews were killed during the Holocaust, a broader definition of the Holocaust would raise the number of deaths to 17 million [12].

Nazi Rationale for Musculoskeletal Experimentation on Concentration Camp Prisoners

As World War II carried on, the Nazi regime found that their soldiers sustained various types of battlefield injuries such as life and limb-threatening bacterial infections—particularly gas gangrene—as a result of contaminated high-energy battlefield trauma, as well as fractures; severe soft-tissue and bone defects; peripheral nerve lacerations; and amputations.

In World War I, gas gangrene occurred in almost 12% of all wounded soldiers, and 22% of those who developed gas gangrene died, directly resulting in the deaths of some 100,000 German soldiers [8, 10]. The Wehrmacht (German army) was acutely aware of this problem during World War II as well, given the heavy toll caused by gas gangrene on the Russian front in 1941-1942 [4]. The German army demanded solutions and thus recruited Schutzstaffel (SS) physicians from the SS medical corps to conduct two sets of musculoskeletal experiments. First, SS researchers examined the efficacy of sulfanilamides on preventing and treating gas gangrene. The second set of experiments were carried out to observe bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration, and the possibility of bone and limb transplantation from one person to another.

Ravensbrück Experiments: Sulfanilamides

Professor Karl Gebhardt, chair of the department of orthopaedic surgery at the University of Berlin, and the leading orthopaedic surgeon in Germany during World War II, oversaw the gas gangrene-sulfanilamide experiments at Ravensbrück concentration camp 90 km north of Berlin by the banks of Lake Schwedt between July 1942 and September 1943. Approximately 130,000 women and children passed through the concentration camp during the war, making Ravensbrück the largest women’s concentration camp. The imprisoned were from both Germany and German-occupied European countries; 40,000 were Polish and 26,000 were Jewish. About 28,000 prisoners were murdered there due to hunger, beating, disease, poor hygiene, overwork, or medical experimentation [15].

Prof. Gebhardt’s assistants included German medical doctors Fritz Fischer, Herta Oberheuser, Rolf Rosenthal, and Gerhard Schiedlausky. Prof. Gebhardt supported surgical treatment for wound infections [18], and thus, his experiments were meant to determine whether Nazi soldiers should be treated surgically at frontline hospitals or by field physicians with sulfanilamides and then sent to a base hospital for further surgical treatment.

Prof. Gebhardt and his team performed preliminary experiments on 20 male prisoners from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp (which is located some 50 km south of Ravensbrück) to determine a mode of infection. In his affidavit, Dr. Fischer described the experimental technique [3]:

An incision was made five to eight centimetres in length and one to one-and-a-half centimetres in depth on the outside of the lower leg in the area of the peroneus longus. The bacterial cultures were put into dextrose, and the resulting mixture was spread into the wound. The wound was then closed […] no serious illnesses resulted.

The “Rabbits” of Ravensbrück

Following the preliminary experiments with the male inmates, forced experiments began on 60 young Polish women at Ravensbrück concentration camp. In fact, the women nicknamed themselves “rabbits” because they felt used like experimental laboratory animals, and because the experiments made them unable to walk; they could only hop [3-5, 19].

Since a serious infection was not achieved with the male inmates, the strains of the bacteria were changed; SS physicians added wood shavings, cloth fibers, dirt, and fragments of glass into the wound to simulate the crust of dirt customarily found in battlefield wounds and to accelerate the process of infection. A mixture of staphylococci, streptococci, clostridium perfringens, and clostridium novyi (oedematiens) was used. Some victims were given sulfanilamides while others received nothing. The victims had considerable pain and fever. Still, it was impossible to tell the difference between those who had been treated with sulfanilamide and the controls by the degree of infection [3].

The SS physicians at Ravensbrück generally performed experimental operations on women more than once, sometimes even as many as eight times. They operated on Barbara Pietrzyk five times in 1942 alone causing left lower limb paralysis. At 16 years of age, she was the youngest of the “rabbits.” Although she survived the initial experiments, Pietrzyk died due to the consequences of the experiments in 1947, at the age of 22 [9].

SS chief medical officer Prof. Ernst-Robert Grawitz visited the camp to oversee the experiments. He concluded that they did not resemble the conditions at the battlefield, since none of the prisoners had died. Because the purpose of the work was to determine the effectiveness of sulfanilamide on bullet wounds, Prof. Grawitz believed further experiments inflicting actual bullet wounds on the women should be performed. Prof. Gebhardt and Dr. Fischer decided to adopt a procedure that would more accurately simulate battlefield conditions without shooting the women.

The normal result of all bullet wounds was a shattering of tissue, which did not exist in the initial experiments. As a result of the injury, the normal flow of blood through the muscle is cut off. The muscle is nourished by the flow of blood from either end. When this circulation is interrupted, the affected area becomes a fertile field for the growth of bacteria; the normal reaction of the tissue against the bacteria is not possible without circulation [3].

Prof. Gebhardt oversaw a new series of experiments involving 24 Polish female prisoners in which the circulation of blood through the muscles was interrupted by tying off the muscles on either end. The resulting necrotic area was then inoculated with the new bacterial strains. This series of experiments resulted in serious infections and five deaths. Satisfied with these results, the SS physicians systematically administered various therapies for the women; some received locally applied sulfanilamide powder, some received local sulfanilamide powder plus sulfanilamide tablets, some received sulfanilamide injections in addition to local sulfanilamide powder and sulfanilamide tablets while others received no therapy at all [3-5].

In another series of experiments, purulence was injected into a number of women’s legs. In the following days, some of them were treated with sulfonamide injections. Abscesses formed in all the women. Some victims developed life-threatening systemic infections [5], and all abscesses required draining (Fig. 1).

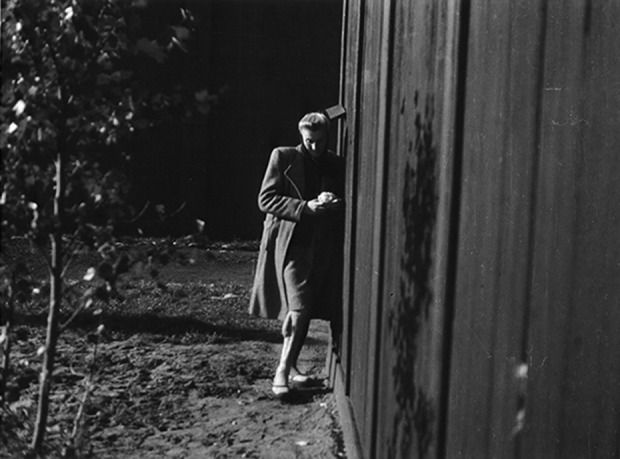

Fig. 1.

The disfigured leg of Maria Kusmierczuk sustained during sulfanilamide experiments is shown. The photograph was taken by a camera secretly smuggled into the camp. Ravensbrück, Germany, October 1944. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Anna Hassa Jarosky and Peter Hassa).

SS physicians performed classical surgical débridement of the infected tissues when sulfanilamide treatment was deemed ineffective, again as a control group. The courses of infection were almost identical in the victims treated with or without sulfanilamides. Postoperative care of the women was entirely inadequate, many of them were not given any analgesics, and the wound dressings were changed inconsistently, if at all.

In Plain Sight

Results of the experiments were presented at the Third Medical Conference of the Consulting Physicians of the German Armed Forces in May 1943, attended by many elite military and civilian physicians. Prof. Gebhardt made a frank and candid report, explaining that the experimental subjects were not volunteers, but concentration camp inmates. The fact that medical experimentation was being carried out on human beings, prisoners rather than volunteers, was explicit. The attendees voiced no criticism.

Apart from the 13 deaths that occurred as an immediate result of gas gangrene, six of the victims were executed so that they could not bear witness to the crimes committed against them. The surviving victims were permanently disabled, both physically and psychologically [3, 5]. Four of the surviving Polish women, Maria Broel-Plater, Jadwiga Dzido (Fig. 2 A-B), Wladyslawa Karolewska (Fig. 3), and Maria Kusmierczuk [17] testified during the Doctors’ Trial and exhibited the scars on their legs Those scars turned into a world-wide symbol for the horrific nature of Nazi experiments on concentration camp prisoners [16].

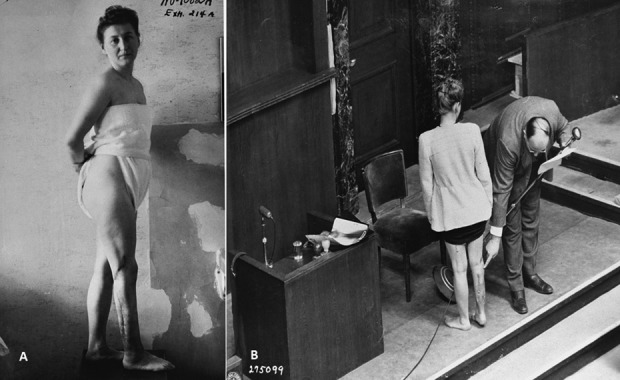

Fig. 2 A-B.

(A) A war crimes investigation photograph of Polish victim Jadwiga Hasa (born Jadwiga Dzido) who was a subject in the sulfanilamide experiments. Note the scars on the right lower leg. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, USA). (B) Leo Alexander MD, medical expert for the United States prosecution during The Doctors’ Trial, points to the scars on Jadwiga Dzido’s leg sustained during sulfanilamide experiments. Nuremberg, Germany, 22 December 1946. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, USA).

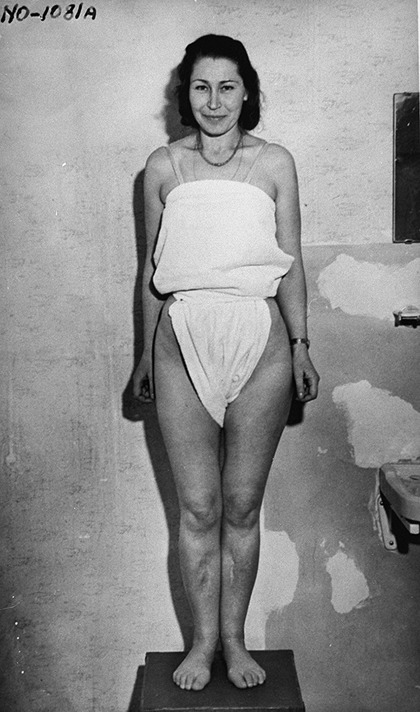

Fig. 3.

A war crimes investigation photograph of Polish victim Wladyslawa Karolewska is shown. Nazi physicians forcibly used Ms. Karolewska as a subject in both the sulfanilamide and bone experiments. Note the scars on both anterior lower legs where tibial grafts were harvested. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, USA).

Another witness, prisoner Dr. Zofia Maczka, worked in the camp hospital during the experiments, and gave detailed information about the experiments and deaths. In her opinion, immediate amputation would have saved the lives of the women who died because of the infections inflicted. During his testimony, Prof. Gebhardt was asked why he did not perform amputations on the women with life-threatening injuries:

It was not that Fischer or I overlooked an amputation, and it is certainly not true that an amputation can save the life of the patient in all cases of gangrene. As I remember the case histories, the most serious patient had a large abscess on the hip. Probably the corresponding glands had been affected. The infection on the calf and the abscess on the hip—what can I amputate? One can amputate when the infection is limited to the calf. [..] I am convinced [...] that we certainly did not overlook anything. As far as one can humanly say, we did what we considered necessary [3].

Sulfa Drugs: What They Knew, and When They Knew It

Sulfanilamide, the first antibiotic, was available in Germany in 1935 [8]. Prof. Gebhardt was aware of German, American, and British studies on sulfanilamides showing them to be useless in the treatment of gas gangrene [17, 19]. In fact, his experiments investigated questions that had long been resolved by valid medical research [17].

The truth was that the experiments were an attempt to defend Prof. Gebhardt’s own approach to the surgical management of contaminated wounds, and his belief that sulfanilamides did not change the course or mortality rate of gas gangrene. During the trial, Prof. Gebhardt avoided direct answers about this, and tried to hide the fact that he had carried out experiments he believed to be unnecessary [4, 5].

Gebhardt has admitted, during the interrogations, that the results of the operations were a foregone conclusion before he commenced the experiments, but even so, carried out the experiments until some deaths had resulted [3].

It goes without saying that the moral distinction between animal and human-subjects research was ignored in these experiments, which used established methodologies from animal models in human experimentation. Biologically the test subjects were regarded as humans, but socially and ethically, their status as humans was denied [14], and surely more-relevant clinical experiments could have been carried out on wound infections in wounded German soldiers. But Prof. Gebhardt’s experiments convinced his nonscientist superiors that sulfanilamides were useless in battlefield wounds complicated by gas gangrene [17].

Ravensbrück Experiments: Bone, Muscle, and Nerve Regeneration

SS physicians carried out a second set of experiments at Ravensbrück to observe the process of bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration, and the possibility of bone and limb transplantation from one person to another. They viewed these experiments as part of a long-term approach for the treatment of soldiers who sustained amputations, pseudoarthrosis, and tissue defects, setting the stage for treatments they expected would continue after the war’s end [3]. Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger, Prof. Gebhardt’s adjunct, took an active part in these second group of experiments. He was assisted by Drs. Fritz Fischer and Herta Oberheuser. Both assistants were familiar with such unethical procedures, as they took part in the gas gangrene-sulfanilamide experiments [4, 5].

Leo Alexander MD, medical expert for the prosecution, and co-author of the Nuremberg Code, explained in the Doctors’ Trial that cortical tibial bone grafts with and without the surrounding periosteum were harvested and either implanted in the tibias of other victims of the experiment, or in the same individual’s contralateral tibia. In some victims, a segment of the fibula was grafted onto the tibia [4, 5].

A large group of muscle experiments also were performed, which included several operations carried out in the same subjects. These involved repeated myomectomies (removal of parts of skeletal muscle) from the same anatomic locations, so that the legs got thinner and weaker over the course of the experiment [3]. During nerve operations, parts of nerves of the lower limbs were resected to see whether nerve regenerated.

These experiments generally were carried out on otherwise-healthy Polish women prisoners similar to the gas gangrene experiments. In fact, some of these women were themselves survivors of the gas gangrene experiments. Wladislawa Karolewska (Fig. 3), who also was a witness in The Doctors’ Trial, was an experimental subject in both the sulfanilamide and bone experiments. She underwent six surgical procedures [3, 4].

Experiments dealing with the transplantation of whole limbs from one person to another were also carried out. Although there are no definitive figures, it is likely that at least 10 such procedures were carried out [3-5]. In his affidavit, Dr. Fischer said:

I was ordered to go to Ravensbrück and perform the operation of removal on that evening. I asked Doctors Gebhardt and Schulze to describe exactly the technique which they wished me to follow. The next morning I drove to Ravensbrück after I had made a previous appointment by telephone. I [..] merely put on my coat, and went to Ravensbrück and removed the bone.

“[..] I returned to Hohenlychen as quickly as possible with the bone which was to be transplanted. In this manner the period between removal and transplantation was shortened. At Hohenlychen the bone was handed over to Professor Gebhardt, and he, together with Doctor Stumpfegger, transplanted it [3].

Meaningless Experimentation

Of course, these bone grafting experiments were senseless. By the time they were being performed in Ravensbrück, sufficient experimental histologic data, as well as surgical and clinical experience had already accumulated. Indeed, SS physicians performed bone grafting experiments even though such surgical procedures had already been proven to work more than a decade earlier, making it clear that the victims of these experiments were being tortured for no plausible scientific purpose [13]. From his affidavits we know that Prof. Gebhardt was aware of the advances around the world about this subject [3].

In her affidavit, Dr. Zdenka Nedvedova-Nejedla, a Czech doctor working in the camp hospital confirmed the atrocities:

High amputations were performed; for example, even whole arms with shoulder blade or legs with iliaca were amputated. These operations were performed mostly on insane women who were immediately killed after the operation by a quick injection of evipan. All specimens gained in operations were carefully wrapped up in sterile gauze and immediately transported to the SS hospital nearby, where they were to be used in the attempt to heal the injured limbs of wounded German soldiers. After operations, no one except SS nurses was admitted to the persons operated on, whole nights they lay without any assistance and it was not permitted to administer sedatives even against the most intensive postoperational pains. From the persons operated on, 11 died or were killed [3].

Like the results from the sulfanilamide experiments, the experiments on bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration were presented and widely discussed at the Third Medical Conference of the Consulting Physicians of the German Armed Forces in May of 1943. Prof. Gebhardt and Dr. Fischer mentioned that several of the victims had died as a result of these experiments in their report. The audience questioned them about technical details but did not voice any concern about the criminality of the experiments [3-5].

The Verdicts

At the end of the Doctors’ Trial, Prof. Gebhardt received a death sentence and was hanged on June 2, 1948. Dr. Fischer received lifetime imprisonment but was released after 7 years and lived to the age of 91. Dr. Oberheuser received 20 years’ imprisonment but was released after 4 years. Drs. Rosenthal and Schiedlausky were tried by the British and received death sentences and were hanged on May 3, 1947 [5, 7]. Dr. Stumpfegger committed suicide at the end of the war.

As it was stated in the opening statement of the prosecution: “These experiments revealed nothing which civilized medicine can use [3].”

The crimes committed under the guise of “research” by these Nazi physicians still haunt the medical community.

Next month, in the concluding article of this two-part series, I will discuss the downfall of the medical profession in Germany during the Nazi era and the ethical issues associated with publishing research by Nazi physicians, including the use of anatomic images depicting Holocaust victims.

Afterword

I last visited the Ravensbrück National Memorial on a cold, wet December day. The trees were bare, and the lake seemed almost motionless. Tranquility was in the air. I walked through the roll-call square as the night rolled in, and imagined it was the same hour that camp inmates stood to be counted, hungry, tired, and shivering in rags under the freezing rain. I heard no cries or screams as I walked to the gate. I was warm in my coat.

Acknowledgment

I thank Sabine Arend PhD, from the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum, for her kind guidance.

Footnotes

A note from the Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Erdem Bagatur, a professor of orthopaedic surgery in Istanbul, Turkey, sent Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® an extraordinary set of historical essays about Nazi musculoskeletal experiments conducted on concentration camp prisoners during World War II. Since this is not ordinarily within the remit of our journal, we took special steps to handle the material in ways that are consistent with the highest standards of ethics and historical research. (To learn more, see my editorial in this month’s issue of CORR®). In this essay, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Bagatur meticulously describes the terrible crimes committed on a mass scale by Nazi physicians and orthopaedic surgeons.

The author certifies that neither he, nor any members of his immediate family, have any commercial associations (such as consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

The opinions expressed are those of the writers, and do not reflect the opinion or policy of CORR® or The Association of Bone and Joint Surgeons®.

References

- 1.Astor M. Holocaust is fading from memory, study finds. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/12/us/holocaust-education.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- 2.BBC News. Syria chemical ‘attack’: What we know. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-39500947. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- 3.Dörner K, Ebbinghaus A, Linne K, Roth K, Weindling P. The Nuremberg Medical Trial 1946/47. Transcripts, Material of the Prosecution and Defense, Related Documents. English Edition. Microfiche Edition Munich, Germany: K. G. Saur; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebbinghaus A. Introduction: Reflections on the medical trial. In: J Eltzschic, M Walter, eds. The Nuremberg Medical Trial 1946/47. Guide to the Microfiche Edition. München, Germany: K. G. Saur; 2001:11–64. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebbinghaus A, Roth KH. Die kriegschirurgischen Experimente in den Konzentrationslagern und ihre Hintergründe. In: A Ebbinghaus, K Dörner, eds. Vernichten und Heilen. Der Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß und seine Folgen. Berlin, Germany: Aufbau-Verlag; 2001:177–218. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst E. A leading medical school seriously damaged: Vienna 1938. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesch JE. The First Miracle Drugs: How the Sulfa Drugs Transformed Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loewenau A. The story of how the Ravensbrück “rabbits” were captured in photos. In P Weindling, ed. From Clinic to Concentration Camp: Reassessing Nazi Medical and Racial Research, 1933-1945. New York, NY; 2017: 221–256. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matheson JM. Infection in missle wounds. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1968;42:347–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitscherlich A, Mielke F. Doctors of Infamy: The Story of Nazi Medical Crimes. New York, NY: Henry Schuman; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niewyk DL, Nicosia FR. The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phemister DB. The classic: Repair of bone in the presence of aseptic necrosis resulting from fractures, transplantations, and vascular obstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1020–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roelcke V. Die Sulfonamid-Experimente in nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslagern: Eine kritische Neubewertung der epistemologischen und ethischen Dimension. Medizinhist J. 2009;44:42–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saidel RG. The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt U. Justice at Nuremberg: Leo Alexander and the Nazi Doctors Trial. Hampshire and New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt U. ‘The scars of Ravensbrück’: Medical experiments and British war crimes policy, 1945-1950. Ger Hist. 2005;23:20–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver JR. Karl Gebhardt (1897-1948): A lost man. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011;41:366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weindling PJ. Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials: From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent. Hampshire and New York, NY: Palgrave-Macmillan; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weindling P, von Villiez A, Loewenau A, Farron N. The victims of unethical human experiments and coerced research under National Socialism. Endeavour. 2016;40:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]