Abstract

Although WeChat is currently one of the fastest growing social media in mainland China, many scholars and researchers are yet to systematically investigate the potential social and psychological consequences of the newly emerging online social network. Based on theory and previous studies, the principal purpose of this present study is to probe and understand whether and how the use of WeChat is related to individuals' friendship quality and psychological well-being. Research participants were a total of 508 college students who completed anonymous questionnaires gauging their WeChat usage behaviors, self-disclosure, friendship quality, and well-being. Using structural equation modeling, results demonstrate that the intensity of WeChat use is significantly correlated with college students' quality of friendships but not with perceived well-being. Moreover, the outcomes also reveal that students' friendship quality is a significant predictor of well-being. However, there is no relationship between online self-disclosure and friendship quality or well-being. Overall, these obtained findings of the empirical study could cast a much-needed light on the nuanced understanding of the certain social and technological affordances of WeChat and how it may ultimately impact individual's quality of life in the new media context.

Keywords: Psychology, Sociology

1. Introduction

In recent years, the booming development of social networking sites (SNSs) has fundamentally impacted how individuals communicate, socially interact, sustain personal relationships, and disseminate information in their everyday lives (Hanna et al., 2017; He et al., 2016). These communication technologies represent an excellent web-based avenue where users can build personal profiles initially, and subsequently connect with other network members with similar interests from distinct demographic, geographical, as well as cultural backgrounds in diversified ways (Dhir and Tsai, 2017; Hsu et al., 2015). Moreover, social media platforms offer a wide variety of recreational activities, consisting of playing computer games, watching online videos, enjoying music, and reading the hot point news (Andreassen et al., 2017; Pang, 2018a). Given that young generations (i.e., college attending students) are highly active users of SNSs, there is a pressing need for more empirical studies to examine the potential influences of these emerging communication tools on their social and psychological development such as online self-disclosure, friendship quality, and psychological well-being (Dhir and Tsai, 2017; Ozimek et al., 2017; Zhan et al., 2016).

Currently, the most dominant mobile app and SNS application among Chinese young adults is WeChat (Weixin in Chinese), which was developed by the Chinese technology giant Tencent in late January 2011 (Zhang et al., 2017). With the advances in network technology and the rapid proliferation of smartphone, WeChat has reached approximately 938 million monthly activated users as of march 2017 (Graziani, 2016; Tencent, 2017). WeChat has similar characteristics to WhatsApp to permit users to release messages in various formats (e.g., texts, videos, voices, and images) to an individual or a specific group in their friend circles. Additionally, it enables members to post text messages, pictures, emojis, web pages, and even small videos to Moments (similar in function to Facebook's Newsfeed), and comment or click the “like” button on others' posts (Chen, 2017). Furthermore, WeChat provides additional functions such as entertainment, shopping, payment, and transactions at the same time (Wen et al., 2016). Collectively, these socio-technical affordances and characteristics of WeChat make it a unique space where young people can efficiently and conveniently communicate and interact with their partners and friends.

However, the majority of previous studies have predominantly focused on the adoption of Facebook, YouTube, or other global SNSs in the western countries (Choi et al., 2017; Hanna et al., 2017; Lomanowska and Guitton, 2016; Yang and Lee, 2018). By contrast, surprisingly little scholarly attention has been paid to the beneficial effects of indigenous SNS use, especially WeChat in mainland China (Dhir and Tsai, 2017; Pang, 2018b). Furthermore, even relatively fewer empirical investigations thus far have uncovered the WeChat use behavior of college students (Gan, 2017), in particular, how they utilize the new media venue to communicate and what effects computer-mediated interaction has on their well-being development. More importantly, prior research has yielded ambiguous results concerning the relation between SNS use and well-being status. Some studies revealed that excessive SNS utilization is linked with increased depressive symptoms and loneliness (Nesi and Prinstein, 2015), whereas other research indicated no relationship (Lönnqvist and Itkonen, 2014), and still others discovered a positive association between SNS use and well-being (Ishii, 2017; Kross et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2016).

Such inconsistency in the results to date could be attributable to the fact that prior studies inclined to adopt overly simplistic measures of SNS use, concentrating mainly on direct causality of these variables. As evidenced in the relevant literature, assessing social media use as time spent or the frequency of the service use is a limited evaluation due to it just measures the partial information of SNS use, which might produce some of the inconsistencies between these studies (Andreassen et al., 2012). Further, recent studies have suggested that intensity of WeChat use is a more holistic conceptualization of emotional attachment and media usage experience in comparison with the conventional measuring method of evaluating service involvement, and it has been widely utilized to gauge both affective and cognitive components of SNS adoption (Dhir et al., 2017; Dhir and Tsai, 2017; Wen et al., 2016). Consequently, scholastic controversies over the effects of social media on users' psychosocial factors have facilitated more in-depth investigations for adequately addressing these sophisticated connections.

In summary, the primary objective of this current study is to fill these aforementioned gaps in earlier research by systematically investigating the possible associations between the intensity of WeChat use, self-disclosure, quality of friendship, and psychological well-being. As such, the work will extend the scope of previous literature which has concentrated mainly on total time spent or frequency of SNS utilization as the significant predictor. Additionally, the exploratory research will be one of the first attempts to uncover the underlying mechanisms between WeChat usage and its diverse outcomes among college students in mainland China. Furthermore, the obtained research results may deeper the understanding of the unique characteristics and functionalities of WeChat, and lead to broader theoretical discussions concerning the actual influence of the emerging computer-mediated technology on people's quality of life in today's saturated media environment (Lee et al., 2018).

2. Background

2.1. WeChat interaction and psychological well-being

Concerning the implications of computer-mediated communication on well-being, two opposing explanatory hypotheses have emerged during the past few years. The displacement hypothesis asserts that Internet activities could decrease the quality of individuals' existing friendships and, thus ultimately decline their well-being (Kraut et al., 1998). An initial batch of investigations have also verified that online communication technologies are negatively related to the real-life friendship quality and well-being due to these available SNSs relationships are superficial and ephemeral, and that they may substitute authentic time of forming and maintaining real-world connections (Ishii, 2017). Conversely, the stimulation hypothesis claims that web-based communication strengthens well-being through its positive influences on social relationships (Valkenburg and Peter, 2007a). Recently, more scientific studies bolster this notion, stating that SNS communication is positively correlated with users' sense of well-being and their quality of friendships (Ishii, 2017; Wen et al., 2016).

These positive effects of online social communication on well-being appear to be attributable to the possibility that individuals' online interaction transforms with the passage of time from communication with complete strangers to communication with those who turn into trusted friends and acquaintances (Valkenburg and Peter, 2007a). Several studies have proposed that by its various functions and characteristics, SNS renders it conveniently for individuals to stay in touch with old and new friends (Chan, 2015; Hu et al., 2017). More importantly, social media serves to the gratification of diverse personal and social demands in online settings, which are also contributing to the well-being (Dhir and Tsai, 2017). Consequently, SNS users are more likely to increase the quality of actual friendships, which further fosters their perceived well-being (Chen et al., 2016). Taking consideration that the predominant feature of WeChat communication is to efficiently extend and maintain individuals' personal friendship networks (Zhang et al., 2017), WeChat interaction is anticipated to enhance college students' well-being and friendship quality. Based on the foregoing, the following hypotheses were therefore formulated:

H1

The intensity of WeChat interaction will be positively associated with students' well-being.

H2

The intensity of WeChat interaction will be positively associated with students' friendship quality.

2.2. WeChat interaction and online self-disclosure

Self-disclosure has been broadly conceptualized as the behavior of revealing any personal information such as geographic locations, interests, as well as pictures when utilizing online social networks (Posey et al., 2010). Ledbetter posited that self-disclosure as the fundamental and specific motivation that could promote web-based interpersonal communication more generally (Ledbetter, 2009). Social web users are reported to disclose themselves indirectly on the computer-mediated communication environment and simultaneously strive to maintain positive impressions (Chen, 2015). Specifically, within the settings of SNS, individuals expose themselves to an online context that reinforces the number and depth of self-disclosure because their experience can reduce both physical and nonverbal cues, discreetly redact their utterances, control their followers, as well as selectively share potentially useful cognitive resources (Trepte and Reinecke, 2013). Therefore, compared with face-to-face interactions, social media users are less willing to be concerned about the self-presentation and more willing to be open to self-disclosure (Walther, 1996).

A growing body of studies has also provided firm support for the positive relationship between social media use and self-disclosure behavior in general. For instance, a longitudinal research conducted on 488 users of SNS demonstrated that social media use is a significant predictor of individual's disposition for online self-disclosure (Trepte and Reinecke, 2013). Building on Trepte and Reinecke's work, Bazarova and her colleague further identified the importance of self-disclosure behavior through social media technologies, indicating that Facebook users utilize diverse media affordances for discoursing with different levels of intimacy online (Bazarova and Choi, 2014). Recent empirical evidence has suggested that social-based media use stimulates young people's online self-disclosure, which then gradually increases their quality of current close friendships (Desjarlais and Joseph, 2017). Other recent investigations corroborated the result that users' perceived opportunities to establish relationships and obtain enjoyment via microblog are positively associated with online self-disclosure (Liu et al., 2016), as do other types of social media (Chen, 2015; Waterloo et al., 2017). Extending this finding to WeChat, because WeChat's basic site structure expands opportunities for self-disclosures of thoughts and feelings on the platform, such as uploading photos, updating status, liking, and commenting, it will be essential to take into account theoretical links between the new media interaction, and subsequent relational outcomes. Thus, the third hypothesis was proposed:

H3

WeChat interaction will be positively associated with students' online self-disclosure.

2.3. The effect of self-disclosure on friendship quality and psychological well-being

Self-disclosure is recognized as the most central component in the development and maintenance of intimate relationships because it can establish mutual understanding, trust, as well as solidarity between people (Bazarova and Choi, 2014). Friendship quality refers to the dyadic relationship that consists of various characteristics such as intimacy, companionship, as well as emotional support (Kiesner et al., 2010). Adolescents and young adults who engage in more intimate self-disclosure through computer-mediated communication are more incline to establish friendships with other individuals (Desjarlais and Joseph, 2017). Additionally, the content of personal information disclosed on the web might be essential for creating intimate relationships as well as enhancing well-being. There is ample evidence for the connection between online self-disclosure and various relational consequences, such as quality of friendship and life satisfaction (Chen, 2015; Huang, 2016; Lomanowska and Guitton, 2016). Based on the structural-path analysis of the research model, Huang discovered that online self-disclosure has a positive and significant impact on Facebook members' satisfaction with present social life (Huang, 2016). Later, using a sample of undergraduate students, Desjarlais and Joseph revealed that technical and contextual features of SNSs could foster the sharing of personal intimate information, which would thereby improve the quality of close friendships (Desjarlais and Joseph, 2017). Nevertheless, the crucial role of self-disclosure on friendship quality and well-being in the WeChat context has received relatively little attention from these researchers. Thus, the present article hypothesized that:

H4

Online self-disclosure will be positively associated with students' friendship quality.

H5

Online self-disclosure will be positively associated with students' well-being.

It is well known that friendship quality is related to well-being. Specifically, individuals with high level of happiness appear to experience better social relationships than those with low level (Jourard, 2005). The positive link between friendship quality and the possession of life satisfaction might be explained by the possibility that social networking sites promote one's feelings of connection and belongingness, thereby, the quality of existing friendships facilitate perceived happiness by supplying intimacy, care, encouragement and assistance from others (Goswami, 2012; Trepte and Reinecke, 2013). Helliwell and Putnam acknowledged that people who interact frequently with close friends were less likely to feel sad, have the low degree of self-esteem and have mental-related symptoms (Helliwell and Putnam, 2004). Recently, Chan analysis of local residents samples in Hong Kong discovered that multimodal connectedness and the frequency of strong-tie interactions could significantly boost well-being (Chan, 2015). Furthermore, building upon this research, Ishii revealed that the total number of friends on LINE (a dominant instant messaging application) was positively correlated with Japanese young people's life satisfaction (Ishii, 2017). Considering that the principal function of WeChat is to obtain instant communication and connect with friends (Zhang et al., 2017), it is naturally expected that the new technology could contribute to greater well-being. Hence, the following hypothesis regarding WeChat friend quality was proposed:

H6

For WeChat users, friendship quality will be positively associated with well-being.

Given that socio-demographic characteristic, especially gender and age have been empirically correlated with a range of other factors, thus, the gender and age are vital variables to be considered in this article. Specifically, prior research indicated that gender and age may affect one's disclosure behaviors in the SNS environment. Concerning gender, females prone to reveal more personal and intimate information to peers than men on SNSs and that online self-disclose behavior can enhance the quality of their social relationships (Waterloo et al., 2017). The underlying reason may lie in the fact that women are traditionally taught to be more expressive and open, while men are expected to restrain in sharing their thoughts and feelings in their communication (Mesch and Beker, 2010). Regarding age, the younger people are more willing to self-disclose than older people in computer-mediated communication contexts (Sponcil and Gitimu, 2013). Besides, social anxiety is another critical factor that may impact online self-disclosure. Based on the social compensation hypothesis, youth adults with high levels of social anxiety may incline to express their inner feelings and concerns in social web due to the decreased audiovisual cues offered by online communication, which would therefore help them develop high-quality online self-disclosure (Lin et al., 2017a). Similarity, Trepte and Reinecke have documented that the SNS environment may encourage individuals to disclose personal information more conveniently and immediately in comparison with face-to-face communication (Trepte and Reinecke, 2013). Furthermore, the lack of social status and non-verbal cues during online interaction also promote users' online self-disclosure practices (Chen, 2015).

3. Methods

3.1. Research model

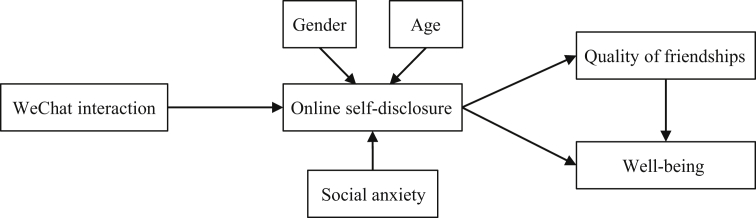

Fig. 1 displays the proposed theoretical model for examining individuals' WeChat usage behavior, online self-disclosure, quality of friendship, and well-being. The hypothesis of the current research is that WeChat interaction may positively affect individual's quality of friendships and well-being. That is, college students who use WeChat more intensity tend to have higher levels of friendship quality and well-being than those who use it less intensity. The study also considered users' gender, age, as well as social anxiety, and their linkages with WeChat interaction, online self-disclosure, and well-being.

Fig. 1.

The research model among WeChat interaction, friendship quality, and well-being.

3.2. Data collection

Participants were derived from a comprehensive university in Lanzhou, a city in Northwestern China. College students were invited to participate in a questionnaire survey about their WeChat use and well-being in a variety of classrooms during the spring semester, 2017. All students were informed that their responses were anonymous and that their participation was entirely voluntary. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Technische Universität Dresden. Of the 667 potential participants, a total of 508 finally completed the survey, yielding response rates of 76.2%. In addition, 55.9% of the participants were male, and 44.1% were female.

3.3. Measurements

3.3.1. WeChat interaction

The scale of WeChat interaction was proposed by Wen et al. (Wen et al., 2016) with minor modifications from Ellison and her colleagues (Ellison et al., 2007), which was used to assess participants' WeChat use intensity. This questionnaire mainly contains three components: the number of total WeChat friends, the amount of time spent on WeChat on a typical day, and a series of Likert-scale attitudinal items to unpack users' emotional connectedness to the service (Cronbach's alpha = .85). Respondents indicated on a five-point rating scale to what extent they agreed with these statements such as ‘WeChat is part of my everyday activity’. The main descriptive results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for WeChat intensity.

| Individual Items and Scale | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| WeChat Intensity (Cronbach's alpha = 0.85) | 2.98 | 0.78 |

| How many total WeChat friends do you have 1 = 50 or less; 2 = 50–100; 3 = 101–150; 4 = 151–200; 5 = more than 200 |

2.44 | 1.31 |

| On a typical day, approximately how much time do you spend on WeChat? 1 = less than 30 min; 2 = 30–60 min; 3 = 1–2 h; 4 = 2–3 h; 5 = more than 3 h |

2.77 | 1.51 |

| WeChat is part of my everyday activity | 3.48 | 0.99 |

| I am proud to tell people I am on WeChat | 2.74 | 0.86 |

| WeChat has become part of my daily routine | 3.53 | 0.92 |

| I feel out of touch when I haven't logged onto WeChat for a day | 2.76 | 1.11 |

| I feel I am part of the WeChat community at the campus | 3.04 | 1.00 |

| I would be sorry if WeChat shut down | 3.09 | 1.08 |

Notes: Unless provided, participants' response ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.3.2. Online self-disclosure

The scale of online self-disclosure originally developed by Gibbs and her colleagues was adopted in the research (Gibbs et al., 2006). A sample question is “I usually communicate about myself for fairly long periods at a time with those I meet online”. Respondents were requested to rate their degree of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale, in which 1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”. Those negatively phrased questions were reverse coded. Reliability coefficient for the 5-item questionnaire was .70.

3.3.3. Social anxiety

The concept of social anxiety typically refers to individuals' social avoidance and distress when confronted with new social situations, circumstances or strangers. The society anxiety scale was derived from earlier studies explored adolescents' social anxiety and their peer relations (La Greca and Lopez, 1998). The scale consists of four items such as “I feel shy around people I don't know”. Participants were asked to estimate how much each item is true for them on a 5-point Likert ranging scale from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Cronbach's coefficient alpha for the present scale was .76.

3.3.4. Quality of friendships

Quality of friendships was evaluated with an adapted version of friendship quality scale from Valkenburg and Peter's research (Valkenburg and Peter, 2007b). The scale mainly consists of four items (e.g., my friends help me to understand myself better) and each item was tested by asking college student participants to assess their agreement to all four statements on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Cronbach's alpha for the 4-item response scale in this study was .78.

3.3.5. Well-being

Well-being generally refers to the global cognitive judgments of a people's quality of life on the basis of his chosen criteria (Ellison et al., 2007). It was gauged by the four-item satisfaction with life scale designed by Diener and his research group (Diener et al., 1985). Examples of the questionnaire items contain “I am satisfied with my life” and “The conditions of my life are excellent.’’ Each statement was estimated with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. These four questions were then averaged to generate a scale of the overall life satisfaction. The 4-item scale yielded a high Cronbach's alpha of .86.

3.3.6. Demographics

The research samples were asked whether they are female (evaluated as 1) or male (evaluated as 2). In addition, participants were asked to respond to their age (on a scale of 1 = 18–20 years old and 5 = 30–32 years old).

4. Results

The current study first presents some preliminary descriptive data to characterize WeChat users and uses, so as to offer fresh insight into whether WeChat is particularly relevant with college students' friendship quality and psychological well-being. Within just a few years, WeChat has already attracted a large number of users on university campuses (Gan, 2017). In the present sample, roughly 93% of the college students the research surveyed were WeChat members. Descriptive analyses indicated that participants' age ranged from 18 to 32 years (M = 2.43, SD = 1.34). There was a representation at different age stages, with the greatest representation aged 18–20 (32.3%) and the smallest aged 30–32 (10.6%). Regarding gender, male (55.9%) accounted for the majority. More importantly, when it comes to specific WeChat use variables, it was discovered that WeChat members spent between 1 and 2 hours on average using WeChat per day and had between 50 and 100 friends listed on their own profile (Table 2).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations of all variables.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. WeChat interaction | 2.98 | .78 | – | ||||||

| 2. Online self-disclosure | 2.63 | .49 | .046 | – | |||||

| 3. Quality of friendships | 3.54 | .55 | .219∗∗ | −.067 | – | ||||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 2.84 | .67 | .036 | −.028 | .147∗∗ | – | |||

| 5. Social anxiety | 2.47 | .74 | .020 | .021 | −.021 | −.041 | – | ||

| 6. Gender | 1.56 | .50 | −.173∗∗ | .039 | −.181∗∗ | −.007 | −.008 | – | |

| 7. Age | 2.43 | 1.34 | .482∗∗ | −.057 | .019 | .032 | −.063 | −.002 | – |

Note: N = 508. M = mean. SD = standard deviations **p < .01.

Pearson's correlations were then conducted to assess the possible relationships among all the scaled variables, and the results are summarized in Table 2. As predicted, intensity WeChat interaction is significantly related to users' quality of friendships (p < .01). Meanwhile, users' quality of friendships is positively correlated with their life satisfaction (p < .01). However, contrary to the hypothesis, WeChat interaction is, as in Table 2, not significantly associated with both life satisfaction and online self-disclosure. Thus, H1 is not statistically supported. In addition, gender is negatively correlated with users' WeChat interaction and their quality of friendships (p < .01), and age is significantly related to WeChat interaction (p < .01). These findings imply that the intensity of WeChat utilization could impact well-being in different ways. Although WeChat helps college students to enhance their real-world quality of friendships, it contributes little to facilitate self-disclosure in an online setting.

To simultaneously unearth the complicated connections between WeChat interactions, quality of friendships, and well-being, the structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied with utilizing the computer program analysis of moment structures (AMOS). College student's gender, age as well as social anxiety were consisted in the model as control variables due to prior research have confirmed that these three variables may potentially impact online self-disclosure (Chan, 2015; Waterloo et al., 2017). The model-generating method proposed by Jöreskog and Sörbom was utilized to establish the structural equation models. Guided by Jöreskog and Sörbom, the first step is to specify an initial research model on the basis of these main assumptions (see Fig. 1), then amend the structural model according to the indications of modification indexes it generates (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993). While such strategy is data-driven, if these modifications are theoretically significant and this conceptual model can be justified through adopting an independent sample, thus the structural model developed by this method can pass the goodness-of-fit indices and become acceptable.

Nevertheless, the initial structural model did not fit sufficiently well, indicating Chi-square = 200.993, RMSEA = 0.162, NFI = 0.093, CFI = 0.067. Additionally, it also indicated the appearance of nonsignificant regression paths. More specifically, the path between WeChat interaction and online self-disclosure was weak. Given that the hypothesized predictive relationship between WeChat interaction and quality of friendships holds greater face validity than that between WeChat interaction and self-disclosure, these nonsignificant paths were eliminated from the current model. As Cheng suggested that, these paths would be eliminated whether trimming proceeded through the use of parameter z scores as the removal standards, and meanwhile theoretically justified associations would be added to the newly created nested structural model (Cheng, 2001).

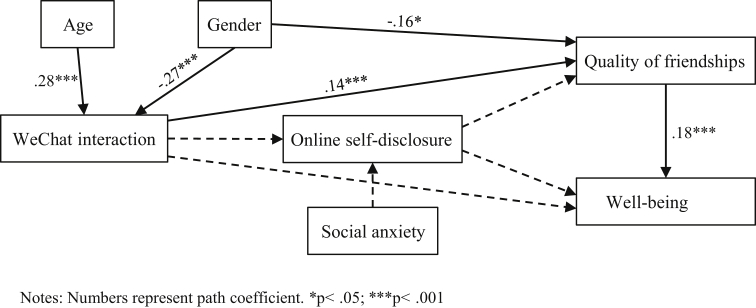

Based on previous results and adjustment indexes created by AMOS, the article modified the initial model to obtain the final model presented in Fig. 2. In order to further refine the model, all non-significant paths (p > .05) were deleted and the models retested. The final model is displayed in Fig. 2 with the removed paths represented by dashed lines. Again, this trimmed model (see Fig. 2) generated a good fit for the research model depicted in Fig. 2, with a p of .457, a CMIN/DF of 4.67, a GFI of .99, an AGFI of .98, an NFI of .97, a RFI of .85, an IFI of 1.00, a TLI of 1.00, a CFI of 1.00, a RMSEA of .00. WeChat interaction is found to be positively and significantly correlated with friendship quality (b = .14, p < .001), whereas it is not positively correlated with well-being. Therefore, H2 is statistically supported. In addition, friendship quality is positively related to well-being (b = .18, p < .001). Gender is negatively related to both WeChat interaction (b = .27, p < .001) and friendship quality (b = .16, p < .05). Age is positively related to WeChat interaction (b = .28, p < .001). However, no significant relationship is discovered between WeChat interaction and online self-disclosure, or between online self-disclosure and quality of friendships or well-being. Thus H2 and H6 are supported, but H3, H4, and H5 are refused.

Fig. 2.

AMOS analysis of the research model.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the key results

The overarching objective of the present study is to explore the underlying mechanism of the potential influence of WeChat use on college students' friendship quality and psychological consequences in the digital age. More specifically, it tests a proposed theoretical research model that attempts to better clarify and explain the empirical association between the intensity of WeChat interaction and users' friendship quality and life satisfaction in light of the unique functions of the new social media technology. In doing so, the results could provide important insights into the college students' WeChat usage behaviors and further advance the thorough understanding of the beneficial effects of the emerging technology at the micro level.

First, this data demonstrate that, students who utilized WeChat more intensity for communication reported higher degrees of friendship quality than those who utilized them less intensity. The result is in line with a previous study that demonstrated a significant positive linkage between social media interaction and quality of existing friendship (Valkenburg and Peter, 2007a). Recently, Ishii discovered that individuals who utilize social media more frequently tend to have more numbers of offline and online friends in Japan (Ishii, 2017). However, contrary to what was originally predicted, the intensity of WeChat use is not strongly associated with the measure of well-being. The results suggest that although WeChat has become unprecedented popularity in such a short period in Chinese society, it does not actually promote people's satisfaction with current life. The possible explanation can be found in research by Mukesh, Mayo, and Goncalves that keeping in touch with online friends may eventually decrease young people’ life satisfaction due to feelings of jealousness linked with the ostentatious content shared on SNSs (Mukesh et al., 2014). Indeed, college students may feel unfavorable when comparing themselves and their real daily lives with the images that their peers portray on SNSs (Vogel et al., 2014). Therefore, these findings are not congruent with the stimulation hypothesis, which claims that computer-mediated communication can facilitate individuals' perceived well-being (Ellison et al., 2007).

Secondly, the results clearly show a positive correlation between quality of friendships and well-being. As demonstrated in prior studies (Ishii, 2017; Zhan et al., 2016), this association may be attributable to the fact that interaction with friends would enhance a source of comfort such as mutual trust, and thus boost the sense of well-being. A rather surprising finding is that online self-disclosure is not discovered to be related to students' friendship quality or well-being. The finding is contrary to previous research suggesting that the increased online self-disclosure is related to closer and higher quality relationships as well as greater life satisfaction (Chen, 2015; Wen et al., 2016). One explanation is that samples in previous studies were mainly from western cultures, mainly including America and Europe. Owing to discrepant cultures between China and the West, specifically the differences between individualistic and collectivist cultures, might lead to members of individualistic cultures more prefer to disclosure themselves through SNSs than do members of collectivist cultures (Cho, 2007). Another possibility is that the online censorship that still prevails on the popular social media and the Internet in mainland China (Zhang and Lin, 2014), Chinese students might be reluctant to disclosure of the private or intimate contents in online settings, even when communicating with a close network of family and friends.

Thirdly, WeChat interaction is negatively related to gender, and gender is negatively linked to online self-disclosure. Specifically, males engaged in far more WeChat activity than did females. They spent more amount of time on WeChat and they possessed more WeChat friends, and, consistent with prior research on social media use behaviors (Waterloo et al., 2017). Moreover, intensity of WeChat use is positively associated with age. The positive link between social media use and age in online settings might be explained by the fact that seniors are more likely to be interacting with others through WeChat than juniors on the campus due to they may need more useful information about jobs and graduation.

Finally, the results indicate that social anxiety is not associated with online self-disclosure. This is clearly inconsistent with early evidence that individuals with social anxiety more tend to express their feelings, opinions as well as concerns in computer-mediated contexts, where they may feel safe and less inhibited (Tian, 2013). This finding may be explained by the reason that college students with higher levels of social anxiety may prefer to avoid social interactions and friendships, and therefore, they would turn to use other forms of entertainment function on WeChat, such as music, movies, and online games to pass the time. This explanation is also consistent with the suggestion that, the utilization of the online media could still convey people's preferences with minimal user interaction as well as social anxiety (Fernandez et al., 2012). Similar results are also reported in recent studies indicating that with the global prevalence of various social media, adopting SNSs has already become individual's habitual behavior, instead of serving special purposes or needs and it is thus independent of their degree of social anxiety (Lin et al., 2017a).

5.2. Theoretical implications

Given the study results, this research offers several important theoretical implications. First, WeChat is one of the most prevalent SNS services in China, yet surprisingly little attention has been given to understanding of this newly emerging platform. Built on the quantitative method, the study attempts to elucidate how using WeChat could contribute to college students' friendships and well-being in Chinese society. In line with earlier studies (Chen, 2015; Wen et al., 2016), the findings demonstrate that WeChat has promoted students' real-world quality of friendship through helping them connect with existing social relationships and contact each other. Second, the study contributes to the well-being literature by validating the positive correlation between quality of friendships and life satisfaction. Specifically, the study makes an early effort to develop a research model and identify why interacting with WeChat leads to positive outcomes. The results imply that if students who want to improve their psychological or mental health, they could first boost the level of quality of existing friendships. Third, although some studies have explored the significant role of social media on social and psychological consequences (Verduyn et al., 2017), they generally tended to concentrate on only American or European college students. Therefore, the results and model presented in this study may provide valuable insight into the psychosocial influence of social media use and simultaneously offer useful knowledge about the association between the friendship quality and psychological well-being in different social settings.

5.3. Practical implications

This study also has several practical implications for social media technology developers, providers and managers. First, a result of potential interest to providers is that communication on WeChat can enhance quality of friendships. Given the fact that WeChat is one of the most favorite computer-mediated platforms today, and young people tend to spend an increasing amount of their daily time on it to keep in touch with old friends and get to know new people. Therefore, providers could design interesting online activities for WeChat users that allow them to efficaciously interact and participate, further promoting establish and maintain social connections with others (Lin et al., 2017b; Pang, 2017). Second, the study demonstrates the crucial role of friendships quality in assisting students to increase the level of life satisfaction. Social media manager could leverage users' deep needs for life satisfaction by providing value-added product or service information in order to stimulate them to actively engage in the form of comments, share, likes and dislikes on WeChat. As suggested earlier, SNSs may also have the potential to facilitate individual's life quality if designers could develop new media interventions targeted at enhancing the beneficial effects (Zhan et al., 2016). Third, the strong effects of gender and age on the WeChat use behavior imply that there is absolutely no one-size-fit-all strategy for the new media development and management. Users with different gender or age may have distinct behaviors and preferences. Therefore, developers could pay careful attention to it and use different strategies for different users to satisfy their various needs, so as to increase the likelihood of the stronger adoption.

5.4. Limitations and future directions

Despite the results of this research have meaningful insights for both researchers and practitioners, some limitations should be pointed out. Firstly, the survey sample is a homogeneous group of university students from mainland China. Consequently, caution would be exercised when generalizing the findings of this study to other demographic populations. Thus, future studies could take consideration of various samples by consisting of WeChat users of diverse groups in other contexts, such as the middle-aged and elderly group. Another limitation concerns the application of the cross-section design in the article, thus the statistically supported connections could only be deemed as correlational (Huang, 2016). Further improvement would be achieved by adopting experimental and longitudinal methods that may establish the causal relations among WeChat communication, self-disclosure, and friendship quality. Moreover, similar with other new media technologies, the continuous engagement in WeChat use may lead to overuse or addiction (Andreassen et al., 2017). In the future study, researchers should unpack the detrimental impact of WeChat usage on the life satisfaction and quality of friendships. Finally, many recent studies in use behavior in social media have suggested that people with different characteristics are varying in the way they think about and interact via the online media (Pang, 2016; Weller, 2016). Hence, a greater set of variables including personality traits of the user on the basis of these previous reports should be evaluated in future research.

6. Conclusion

This present study is an initial effort to uncover the underlying mechanisms through which WeChat may influence college students' friendships as well as well-being in mainland China. Various features of WeChat and the possible socio-psychological implications were comprehensively explored. The study demonstrates that the intensity of WeChat use is associated with students' better quality of social relationships. As mentioned earlier, social media platforms provide novel avenues for individuals to interact with strong and weak ties that are in the same physical location or geographically dispersed in daily life (Dhir and Tsai, 2017; Ramadan, 2017). There is also suggestive evidence that friending on WeChat may improve individuals' perception of their quality of life. Therefore, the study could shed favorable light on the role of the new technology in contributing to friendships and well-being in contemporary society.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Hua Pang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the SLUB/TU Dresden.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Andreassen C.S., Pallesen S., Griffiths M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017;64:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G.S., Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012;110(2):501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova N.N., Choi Y.H. Self-disclosure in social media: extending the functional approach to disclosure motivations and characteristics on social network sites. J. Commun. 2014;64(4):635–657. [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. Multimodal connectedness and quality of life: examining the influences of technology adoption and interpersonal communication on well-being across the life span. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2015;20(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Liu Y., Zou M. Home location profiling for users in social media. Inf. Manag. 2016;53(1):135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Self-disclosure patterns among Chinese users in SNS and face-to-face communication. Int. J. Interact. Commun. Syst. Technol. 2015;5(1):55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. WeChat use among Chinese college students: exploring gratifications and political engagement in China. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2017;10(1):25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng E.W. SEM being more effective than multiple regression in parsimonious model testing for management development research. J. Manag. Dev. 2001;20(7):650–667. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.H. Effects of motivations and gender on adolescents' self-disclosure in online chatting. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007;10(3):339–345. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y.K., Seo Y., Yoon S. E-WOM messaging on social media: social ties, temporal distance, and message concreteness. Internet Res. 2017;27(3):495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais M., Joseph J.J. Socially interactive and passive technologies enhance friendship quality: an investigation of the mediating roles of online and offline self-disclosure. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017;20(5):286–291. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A., Kaur P., Lonka K., Tsai C.-C. Do psychosocial attributes of well-being drive intensive Facebook use? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;68:520–527. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A., Tsai C.-C. Understanding the relationship between intensity and gratifications of Facebook use among adolescents and young adults. Telematics Inf. 2017;34(4):350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R.A., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez K.C., Levinson C.A., Rodebaugh T.L. Profiling: predicting social anxiety from Facebook profiles. Soc. Psycho. Pers. Sci. 2012;3(6):706–713. [Google Scholar]

- Gan C. Understanding WeChat users’ liking behavior: an empirical study in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;68:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J.L., Ellison N.B., Heino R.D. Self-presentation in online personals: the role of anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and perceived success in Internet dating. Commun. Res. 2006;33(2):152–177. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami H. Social relationships and children’s subjective well-being. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2012;107(3):575–588. [Google Scholar]

- Graziani T. 2016. WeChat Impact Report 2016: All the Latest WeChat Data.https://walkthechat.com/wechat-impact-report-2016/ Retrieved February 13, 2017, from. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna E., Ward L.M., Seabrook R.C., Jerald M., Reed L., Giaccardi S. Contributions of social comparison and self-objectification in mediating associations between facebook use and emergent adults' psychological well-being. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017;20(3):172–179. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Zheng X., Zeng D., Luo C., Zhang Z. Exploring entrainment patterns of human emotion in social media. PLoS One. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell J.F., Putnam R.D. The social context of well-being. Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci. 2004;359(1449):1435–1446. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M.-H., Tien S.-W., Lin H.-C., Chang C.-M. Understanding the roles of cultural differences and socio-economic status in social media continuance intention. Inf. Technol. People. 2015;28(1):224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Gu J., Liu H., Huang Q. The moderating role of social media usage in the relationship among multicultural experiences, cultural intelligence, and individual creativity. Inf. Technol. People. 2017;30(2):265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.-Y. Examining the beneficial effects of individual’s self-disclosure on the social network site. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;57:122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K. Online communication with strong ties and subjective well-being in Japan. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;66:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K.G., Sörbom D. United States of America: Scientific Software International; 1993. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. [Google Scholar]

- Jourard S.M. Self-disclosure: an experimental analysis of the transparent self. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2005;63(12):1438–1443. http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1972-27107-000 [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J., Nicotra E., Notari G. Target specificity of subjective relationship measures: understanding the determination of item variance. Soc. Dev. 2010;14(1):109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R., Patterson M., Lundmark V., Kiesler S., Mukophadhyay T., Scherlis W. Internet paradox: a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 1998;53(9):1017–1031. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017. http://psycnet.apa.org/buy/1998-10886-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E., Verduyn P., Demiralp E., Park J., Lee D.S., Lin N. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnqvist J.-E., Itkonen J.V. It's all about extraversion: why Facebook friend count doesn’t count towards well-being. J. Res. Pers. 2014;53:64–67. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca A.M., Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1998;26(2):83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-05537-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter A.M. Measuring online communication attitude: instrument development and validation. Commun. Monogr. 2009;76(4):463–486. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Chung J.E., Park N. Network environments and well-being: an examination of personal network structure, social capital, and perceived social support. Health Commun. 2018;33(1):22–31. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1242032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Li S., Qu C. Social network sites influence recovery from social exclusion: individual differences in social anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;75:538–546. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-H., Hsu C.-L., Chen M.-F., Fang C.-H. New gratifications for social word-of-mouth spread via mobile SNSs: uses and gratifications approach with a perspective of media technology. Telematics Inf. 2017;34(4):382–397. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Min Q., Zhai Q., Smyth R. Self-disclosure in Chinese micro-blogging: a social exchange theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016;53(1):53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lomanowska A.M., Guitton M.J. Online intimacy and well-being in the digital age. Internet Interv. 2016;4:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesch G.S., Beker G. Are norms of disclosure of online and offline personal information associated with the disclosure of personal information online? Hum. Commun. Res. 2010;36(4):570–592. [Google Scholar]

- Mukesh M., Mayo M., Goncalves D. Well-being paradox of social networking sites: maintaining relationships and gathering unhappiness. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2014;2014(1):14709. [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J., Prinstein M.J. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015;43(8):1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozimek P., Baer F., Förster J. Materialists on Facebook: the self-regulatory role of social comparisons and the objectification of Facebook friends. Heliyon. 2017;3(11) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Understanding key factors affecting young people’s WeChat usage: an empirical study from uses and gratifications perspective. Int. J. Web Based Communities. 2016;12(3):262–278. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Is smartphone creating a better life? Exploring the relationships of the smartphone practices, social capital and psychological well-being among college students. Int. J. Adv. Media Commun. 2017;7(3):205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Mobile communication and political participation: unraveling the effects of mobile phones on political expression and offline participation among young people. Int. J. Electron. Govern. 2018;10(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Understanding the effects of WeChat on perceived social capital and psychological well-being among Chinese international college students in Germany. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2018;70(3):288–304. [Google Scholar]

- Posey C., Lowry P.B., Roberts T.L., Ellis T.S. Proposing the online community self-disclosure model: the case of working professionals in France and the UK who use online communities. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2010;19(2):181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan R. Questioning the role of Facebook in maintaining Syrian social capital during the Syrian crisis. Heliyon. 2017;3(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponcil M., Gitimu P. Use of social media by college students: relationship to communication and self-concept. J. Technol. Res. 2013;4:1–13. http://www.aabri.com/copyright.html [Google Scholar]

- Tencent . 2017. Tencent Announces 2017 First Quarter Results.https://www.tencent.com/en-us/news_timeline.html Retrieved May 23, 2017, from. [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q. Social anxiety, motivation, self-disclosure, and computer-mediated friendship: a path analysis of the social interaction in the blogosphere. Commun. Res. 2013;40(2):237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Trepte S., Reinecke L. The reciprocal effects of social network site use and the disposition for self-disclosure: a longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013;29(3):1102–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. Online communication and adolescent well-being: testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 2007;12(4):1169–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. Preadolescents’ and adolescents' online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev. Psychol. 2007;43(2):267–277. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn P., Ybarra O., Résibois M., Jonides J., Kross E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being: a critical review. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2017;11(1):274–302. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E.A., Rose J.P., Roberts L.R., Eckles K. Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychol. Popular Media Cult. 2014;3(4):206–222. http://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2014-33471-001 [Google Scholar]

- Walther J.B. Computer-mediated communication impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Commun. Res. 1996;23(1):3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Waterloo S.F., Baumgartner S.E., Peter J., Valkenburg P.M. Norms of online expressions of emotion: comparing facebook, twitter, instagram, and WhatsApp. New Media Soc. 2017;20(5):1813–1831. doi: 10.1177/1461444817707349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller K. Trying to understand social media users and usage: the forgotten features of social media platforms. Online Inf. Rev. 2016;40(2):256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Geng X., Ye Y. Does the use of WeChat lead to subjective well-being?: the effect of use intensity and motivations. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016;19(10):587–592. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Lee Y. Interactants and activities on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter: associations between social media use and social adjustment to college. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2018:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan L., Sun Y., Wang N., Zhang X. Understanding the influence of social media on people’s life satisfaction through two competing explanatory mechanisms. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2016;68(3):347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.-B., Li Y.-N., Wu B., Li D.-J. How WeChat can retain users: roles of network externalities, social interaction ties, and perceived values in building continuance intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;69:284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Lin W.-Y. Political participation in an unlikely place: how individuals engage in politics through social networking sites in China. Int. J. Commun. 2014;8:21–42. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2003 [Google Scholar]