Abstract

Influenza B is a common viral illness in childhood. We report a 5-year-old previously healthy girl admitted with facial edema that developed severe acute myocarditis from influenza B infection. As her clinical course progressed, she ultimately developed severe, acute heart failure requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for support.

Keywords: influenza, myocarditis, influenza B

Introduction

Influenza B is a common viral illness in childhood. A well-known complication of influenza B is myositis, 1 which may result in rhabdomyolysis-associated acute kidney injury; however, myocarditis is a rarely reported complication of this virus. We report a 5-year-old previously healthy girl admitted with facial edema who developed severe acute myocarditis from influenza B infection. As her clinical course progressed, she ultimately developed severe, acute heart failure requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for support.

Case Description

A previously healthy 5-year-old female presented to the emergency department with a recent history of mild upper respiratory symptoms and a chief complaint of generalized facial edema and myalgia.

On presentation, the patient was afebrile, tachycardic with a heart rate of 133 beats per minute, normotensive at 110/64, tachypneic at 28 breaths per minute, and saturating 95% in room air. On examination, she appeared fatigued but nontoxic, and was noted to have mild periorbital and facial edema. Her cardiac examination was normal with clear S1 and physiologically split S2 without murmurs, and there was no hepatomegaly. Complete blood count, electrolytes, and liver and kidney function testing were within normal limits. Initial chest X-ray showed no evidence of cardiomegaly or lung pathology.

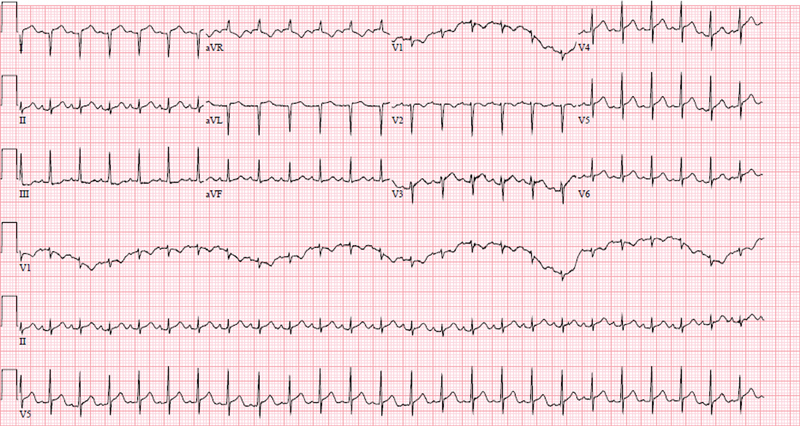

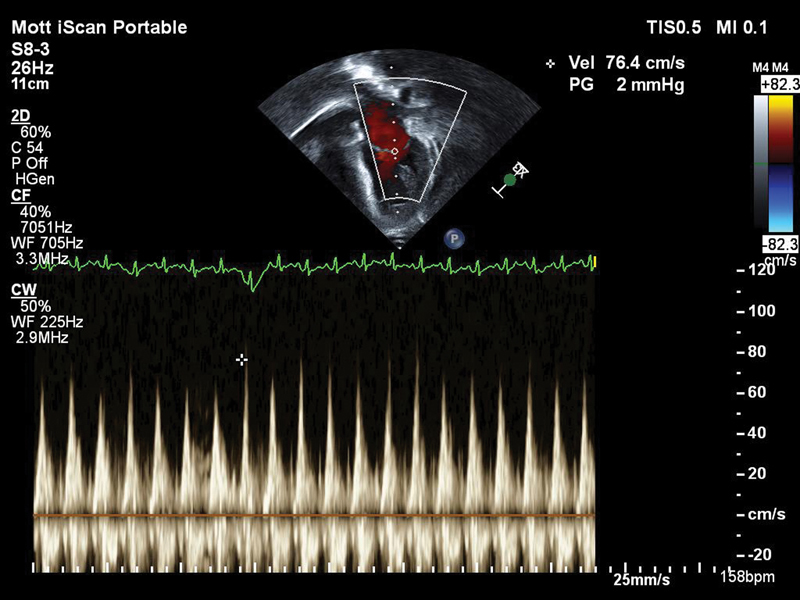

Given persistent tachycardia despite fluid resuscitation, she was admitted to the general pediatric floor, and after overnight observation, her facial edema had improved. She remained tachycardic with heart rates ranging from 140 to 150 beats per minute. An electrocardiogram (ECG) approximately 20 hours after admission showed sinus tachycardia with low-voltage QRS in II, aVR, and V1, right axis deviation (139 degrees in the frontal plane), and nonspecific ST–T wave changes ( Fig. 1 ). Her examination at this point changed and she had evidence of decreased peripheral perfusion including diminished distal pulses and cool extremities, as well as tachypnea and increased work of breathing. Repeat chest X-ray revealed a mildly enlarged cardiopericardial silhouette. Because of the X-ray findings and her concerning examination, an echocardiogram was obtained and revealed a small, localized anterior and rightward pericardial effusion with resulting right atrial compression, underfilling of the right ventricle, moderately depressed right ventricular systolic function, moderately to severely depressed left ventricular systolic function, and an ejection fraction of 44% (Z-score for age: –3.90). The mitral inflow velocity varied with respiration but did not clearly demonstrate tamponade physiology ( Fig. 2 ). Simultaneously, respiratory viral panel returned positive for Influenza B, and troponin level returned elevated at 1.18 ng/mL. Given her rapidly deteriorating clinical picture, she was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram 20 hours after admission.

Fig. 2.

Echocardiogram 20 hours after admission: color flow Doppler over the mitral valve demonstrating variation of mitral valve inflow with respiration, but not demonstrating clear tamponade.

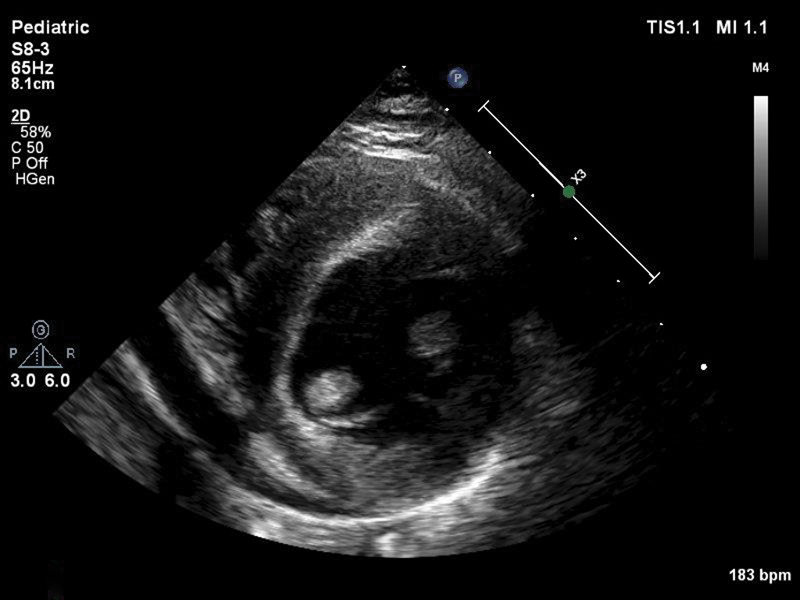

Upon arrival to the pediatric intensive care unit and approximately 24 hours after her hospital admission, she had rapid cardiovascular decompensation and required emergent endotracheal intubation and resuscitation including cardiovascular support with milrinone, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and vasopressin. A repeat echocardiogram approximately 8 hours after the first demonstrated severely depressed to akinetic left ventricular function and mild increase in the size of her pericardial effusion following fluid resuscitation to a diameter of 10 mm ( Fig. 3 ). Given the size of the localized effusion and no clear evidence of tamponade, it was felt that her hemodynamic instability was secondary to her depressed left ventricular function and no pericardiocentesis was performed. Oseltamivir, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day were initiated that evening. Despite maximal medical support, she had worsening lactic acidosis and hypotension and therefore was cannulated onto venoarterial ECMO (VA-ECMO) the next morning. She underwent atrial septostomy following cannulation for left atrial decompression that day. She remained on VA-ECMO circuit for 9 days and was extubated after 21 days. She underwent pericardial window and drain placement on the ninth day of VA-ECMO given persistent tachycardia and evidence of stable but persistent right atrial collapse despite return of left ventricular contractility on her echocardiogram and was decannulated the same day. For her influenza B related fulminant myocarditis, she received a total of 2 g/kg of IVIG, oseltamivir for 5 days, and methylprednisolone for 5 days. She was discharged home after 36 days in the hospital with no serious sequealae. Echocardiogram at time of discharge revealed normal left ventricular size and function, mildly dilated right ventricle with qualitatively normal function, mildly dilated right atrium, no pericardial effusion, and an ejection fraction of 65%.

Fig. 3.

Echocardiogram 30 hours after admission: parasternal short axis view demonstrating 10 mm localized effusion anterior to the right ventricle.

Discussion

We report on a case of fulminant myocarditis due to influenza B in a previously healthy 5-year-old child to highlight the rare but life-threatening complications of influenza B infection and also the nonspecific presenting symptoms in this rapidly evolving case.

Pediatric mortality secondary to influenza B is less than 5% 1 ; however, a recent study suggests that mortality secondary to acute myocarditis is 7%. 2 Viral infection is the most common cause of acute myocarditis in pediatrics, most commonly caused by enterovirus and adenovirus, as well as parvovirus B19 and the herpes virus family. 3 There are at least two documented cases in the literature of fatal myocarditis secondary to influenza B, one in a 5-year-old female 4 and one in a 6-year-old female. 5 Additional cases of influenza B associated myocarditis have been reported and include a 4-year-old female requiring ECMO support and a 15-year-old male with symptoms mimicking coronary artery disease but without need for additional hemodynamic support, both with full recovery. 6 7

Typically, influenza B is associated with presenting symptoms of fevers, chills, headaches, malaise, cough, emesis, and diarrhea. Clinical manifestations of the virus include otitis media, croup, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia. It is notable that our patient reported nonspecific symptoms of fevers, cough, and rhinorrhea, as well as headaches and fatigue in the week preceding her presentation, which largely had resolved at time of presentation. The other reported cases of influenza B related myocarditis in pediatric patients document different, yet nonspecific presentations ( Table 1 ). A common theme of our case with previously reported cases is the rapid progression of cardiogenic shock within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. 4 5 6 We believe that the persistent tachycardia was the primary clue to her underlying diagnosis and evolving clinical picture.

Table 1. Clinical presentations of reported cases of influenza B myocarditis.

| Age/gender | Clinical presentation | Vital signs on admission | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-y-old female | Chest pain, diarrhea, vomiting, weakness, lethargy No fever, no cough |

Tachycardia (140 bpm), hypotension (systolic blood pressure 70) | Craver et al, 1997 5 |

| 4-y-old female | Abdominal pain, emesis, lethargy | Unavailable | Tabbutt et al, 2004 6 |

| 5-y-old female | Abdominal pain, lethargy, recent febrile upper respiratory tract infection | Tachycardia (140 bpm), hypotension (systolic blood pressure 75) | Frank et al, 2010 4 |

| 15-y-old male | Chest pain, febrile illness, diarrhea | Regular rate (80 bpm), normotension (120/65) | Muneuchi et al, 2009 14 |

| 5-y-old female | Facial edema, myalgia, recent febrile upper respiratory tract infection | Tachycardia (130 bpm), normotension (110/64) | McCormick et al, this study |

Abbreviation: bpm, beats per minute.

Myocarditis associated with influenza A infections is somewhat more common than influenza B but also relatively rare. Influenza A infections are associated with transient ECG changes 8 as well as acute myocardial infarction in adults, the latter thought to be a result of the proinflammatory state caused by the virus. 9 Extrapulmonary infections from influenza A such as myocarditis have been well documented especially during seasonal pandemics such as those related to H1N1 influenza. 10 Comparing and contrasting the clinical presentations of influenza A and influenza B myocarditis would be potentially of interest but is currently limited due to the low incidence of influenza B myocarditis.

The treatment of acute myocarditis is largely supportive with a goal of obtaining hemodynamic stability as many children with acute myocarditis recover spontaneously with improvement of their cardiac function. 11 IVIG is frequently used in patients with acute myocarditis; however, few studies have been done in pediatric patients, and there is not strong evidence that use of IVIG promotes myocardial recovery or survival. 12 13 Similarly, steroids have not been shown to significantly affect outcomes of viral myocarditis. A few studies suggest left ventricular ejection fraction at follow-up is improved with steroid treatment, but these results are variable. Mortality was not reduced in patients treated with corticosteroids. Most studies of corticosteroid use in myocarditis have been small trials, and thus larger trials may show more promising evidence. 14 Ultimately, many patients with fulminant myocarditis are refractory to pharmacologic methods of hemodynamic support, and mechanical circulatory support through ECMO or temporary ventricular assist device is required. 15 A review of pediatric acute myocarditis cases requiring ECMO revealed a survival of 61% with most mortality resulting in patients with multiple organ failure. 16

The reported case highlights the importance of persistent sinus tachycardia and the high clinical suspicion that is needed for prompt recognition of rapidly progressive cardiogenic shock. The presenting symptoms of myocarditis are often nonspecific and may be limited to persistent sinus tachycardia not responding to intravenous fluids and preceded by a viral process. Early identification of evolving cardiogenic shock and initiation of appropriate hemodynamic supportive therapy including ECMO can allow for spontaneous improvement of cardiac function in some patients. Additionally, influenza B myocarditis is a rare but potentially devastating condition. Further studies to better characterize this disease presentation may provide insight into this rare complication of a common disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Pamela Davis, MD, and Dr. Kayla Bronder, MD, of the Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan, for their involvement in care of this patient and for their contributions to the review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Nicholson K G. Clinical features of influenza. Semin Respir Infect. 1992;7(01):26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghelani S J, Spaeder M C, Pastor W, Spurney C F, Klugman D. Demographics, trends, and outcomes in pediatric acute myocarditis in the United States, 2006 to 2011. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(05):622–627. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber M A, Ashworth M T, Risdon R A, Malone M, Burch M, Sebire N J. Clinicopathological features of paediatric deaths due to myocarditis: an autopsy series. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(07):594–598. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.128686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank H, Wittekind C, Liebert U G et al. Lethal influenza B myocarditis in a child and review of the literature for pediatric age groups. Infection. 2010;38(03):231–235. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craver R D, Sorrells K, Gohd R. Myocarditis with influenza B infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16(06):629–630. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199706000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabbutt S, Leonard M, Godinez R I et al. Severe influenza B myocarditis and myositis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(04):403–406. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000123555.10869.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muneuchi J, Kanaya Y, Takimoto T, Hoshina T, Kusuhara K, Hara T.Myocarditis mimicking acute coronary syndrome following influenza B virus infection: a case report Cases J 200926809. Doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-6809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ison M G, Campbell V, Rembold C, Dent J, Hayden F G. Cardiac findings during uncomplicated acute influenza in ambulatory adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(03):415–422. doi: 10.1086/427282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren-Gash C, Smeeth L, Hayward A C. Influenza as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction or death from cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(10):601–610. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onitsuka H, Imamura T, Miyamoto N et al. Clinical manifestations of influenza a myocarditis during the influenza epidemic of winter 1998-1999. J Cardiol. 2001;37(06):315–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Filippo S. Improving outcomes of acute myocarditis in children. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;14(01):117–125. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2016.1114884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drucker N A, Colan S D, Lewis A B et al. Gamma-globulin treatment of acute myocarditis in the pediatric population. Circulation. 1994;89(01):252–257. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klugman D, Berger J T, Sable C A, He J, Khandelwal S G, Slonim A D. Pediatric patients hospitalized with myocarditis: a multi-institutional analysis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31(02):222–228. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H S, Wang W, Wu S N, Liu J P.Corticosteroids for viral myocarditis Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20131010CD004471. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004471.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acker M A.Mechanical circulatory support for patients with acute-fulminant myocarditis Ann Thorac Surg 200171(3, Suppl):S73–S76., discussion S82–S85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajagopal S K, Almond C S, Laussen P C, Rycus P T, Wypij D, Thiagarajan R R. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the support of infants, children, and young adults with acute myocarditis: a review of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(02):382–387. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181bc8293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]