Abstract

High-mannose-type glycans (HMTGs) decorating viral spike proteins are targets for virus neutralization. For carbohydrate-binding proteins, multivalency is important for high avidity binding and potent inhibition. To define the chemical determinants controlling multivalent interactions we designed glycopeptide HMTG mimetics with systematically varied mannose valency and spacing. Using the potent antiviral lectin griffithsin (GRFT) as a model, we identified by NMR spectroscopy, SPR, analytical ultracentrifugation, and micro-calorimetry glycopeptides that fully recapitulate the specificity and kinetics of binding to Man9GlcNAc2Asn and a synthetic nonamannoside. We find that mannose spacing and valency dictate whether glycopeptides engage GRFT in a face-to-face or an intermolecular binding mode. Surprisingly, although face-to-face interactions are of higher affinity, intermolecular interactions are longer lived. These findings yield key insights into mechanisms involved in glycan-mediated viral inhibition.

Keywords: antiviral agents, carbohydrates, glycans, multivalency, oligomerization

Surface-displayed glycans play central roles in biology, acting as mediators of cell adhesion and signaling, bacteria–and virus–host interactions, and even protein fate.[1] For many viruses, N-linked high-mannose oligosaccharides are especially important.[2] While oligomannosides coat the surface of some viruses, thereby providing protection from immune surveillance, they can also be the targets of neutralizing antibodies as well as carbohydrate-binding proteins (collectively known as lectins) that are mannose-specific.[3] Indeed, some lectins represent the most potent antivirals known, and can neutralize viruses such as HIV, HCV, influenza, and Ebola virus at nm to pm concentrations.[3c,4]

The extraordinary potency exhibited by some lectins is often attributed to multivalency. Multivalent interactions can occur in these systems because lectins usually exist as oligomers or contain more than one carbohydrate-binding site, and branching glycan structures present more than one arm for binding. Despite interest in these phenomena and their importance in biology, unraveling the molecular determinants that control specificity and avidity has been challenging. Complex glycan structures are not easily obtained nor systematically altered, thus synthetic glycan mimics can be of great value for interrogating these complex interactions. For example, studies with synthetic mucins have revealed that dramatic changes in the recognition and mode of binding can occur depending on the mucin size and carbohydrate number.[5] Such studies have not been undertaken for full-length oligomannosides and antiviral lectins, despite their importance for understanding the mechanisms that lead to potency, avidity, and virus neutralization.

To this end, we sought to develop a system using an oligomannose-binding antiviral lectin of therapeutic importance together with synthetic glycopeptides designed for systematic control of mannose valency as well as the distance and flexibility between mannose units. Our ultimate goal was to design glycopeptides that could faithfully mimic Man9GlcNAc2Asn (Man-9) interactions, thus allowing us to uncover the determinants that control multivalent binding. NMR and SPR spectroscopy, microcalorimetry, and analytical ultracentrifugation would yield affinities and kinetics, as well as reveal modes of binding, including formation of higher order structures. As a model for interrogating multivalent oligomannose interactions we used the mannose-binding lectin griffithsin (GRFT), a homodimeric protein that contains three mannose-binding sites per subunit.[6] The triangular arrangement of these binding sites facilitates multivalent interactions.

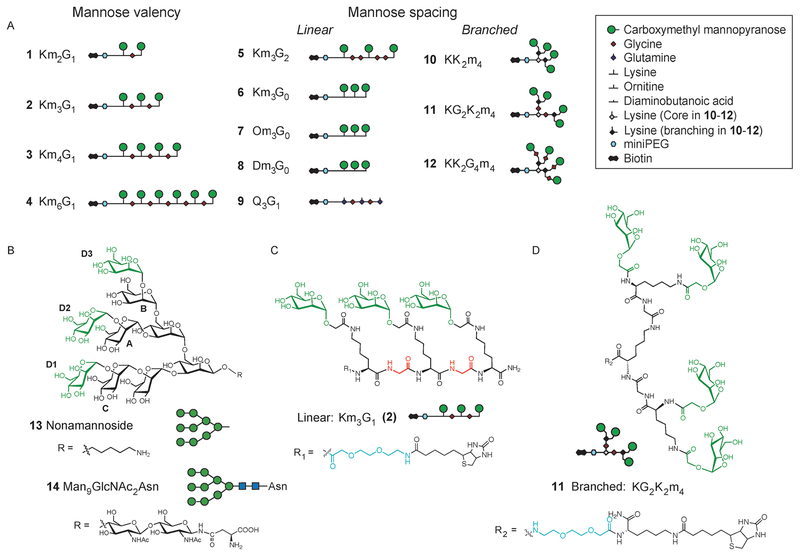

To mimic natural oligomannosides we generated peptide-based scaffolds that present linear (1–9) and branched (10–12) mannose displays by using solid-phase synthesis (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information). Amino acids bearing a side chain and/or a-amino group were positioned to introduce mannose units at desired sites: following deprotection, carboxymethyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-mannopyranose was coupled to free amino groups (see Scheme S1 in the Supporting Information).[7] In addition to mannose valency (1–4), mannose spacing was controlled by altering the side-chain length (6–8), backbone composition (6, 2, and 5), or scaffold branching (10–12). A nonglycosylated peptide Q3G1 (9) served as a negative control.

We first measured the affinities and stoichiometries of glycopeptide binding to GRFT by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Among the homologous linear glycopep-tides 1–4, the equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) decreased by two orders of magnitude as the number of mannoses increased from 2 to 6. Coincident with this trend, the stoichiometries of binding decreased with increasing valency (Table 1, and see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). For example, Km6G1 (4) binds GRFT with a stoichiometry (n) of 0.5, which shows that 4 engages two equivalents of GRFT. The stoichiometries for the linear KmGn constructs suggest that when the number of mannoses exceeds the number of mannose-binding sites, a single glycopeptide molecule engages two GRFT subunits.

Table 1:

ITC analysis of synthetic glycopeptides and oligomannosides binding to GRFT.

| Compound | Name | Kd [μM] | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Km2G1 | 33.24 ± 0.94 | 1.56 ± 0.01 |

| 2 | Km3G1 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.24 |

| 3 | Km4G1 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.68 ± 0.03 |

| 4 | Km6G1 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.05 |

| 5 | Km3G2 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 1.16 ± 0.25 |

| 6 | Km3G0 | 0.88 ± 0.30 | 0.98 ± 0.11 |

| 7 | Om3G0 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.94 ± 0.19 |

| 8 | Dm3G0 | 2.23 ± 0.32 | 1.38 ± 0.17 |

| 9 | Q3G1 | nd[a] | nd[a] |

| 10 | KK2m4 | 5.21 ± 0.05 | 1.96 ± 0.09 |

| 11 | KG2K2m4 | 6.43 ± 0.83 | 1.45 ± 0.12 |

| 12 | KK2G4m4 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 1.08 ± 0.08 |

| 13 | nonamannoside | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 1.42 ± 0.47 |

| 14 | Man9GlcNAc2Asn[b] | 0.54 ± 0.27 | 1.39 ± 0.12 |

Not determined; no binding observed.

Concentration determined experimentally by fluorescent derivatization (see the Supporting Information and Figure S2 therein).

We next analyzed the effects of glycan spacing or density on binding to GRFT for the five linear trivalent constructs Km3G2, Km3G1, Km3G0, Om3G0, and Dm3G0 (5, 2, 6–8, respectively). In this series, because mannose valency is fixed at three while mannose spacing is varied, we can compare the affinities and stoichiometries as a function of mannose distances. Overall these trivalent mimetics (2 and 5–7) bound GRFT with a stoichiometry of 1, except for Dm3G0 (8) that binds with a stoichiometry of 1.5 and has a lower Kd value than the other trivalent constructs (Table 1). Although Dm3G0 differs from its next homologue Om3G0 by only one methylene group per side chain, this small change has a significant impact on binding. In particular, the increase in stoichiometry from 1 to 1.5 for 7 versus 8 suggests that in 8, the more closely spaced mannose units are unable to engage all three mannose binding sites, thereby allowing for additional equivalents of 8 to bind.

The effect of mannose spacing was especially pronounced when comparing results for the branched, tetravalent glycopeptides 10–12. This series was designed to present two pairs of mannose residues with variable spacing, determined by the presence or absence of additional glycine residues, analogous to different oligomannoside structures (Figure 1). Within the series, glycopeptide 10 (KK2m4) has the shortest spacing between adjacent mannoses, KG2K2m4 (11) contains two pairs of closely spaced mannoses (each coupled to one Lys) separated by a longer linker (Figure 1d), and KK2G4m4 (12) has the longest distance between adjacent mannoses and mannose pairs by incorporation of four glycines. ITC studies showed that 12 binds GRFT with a stoichiometry of 1, while 10 and 11 bind GRFT with respective stoichiometries of 2 and 1.5 (Table 1). A striking difference in the affinities among the branched mimetics was observed: compared to glycopeptides 10 and 11, the Kd value for 12 was approximately 30-fold lower, thus making its affinity comparable to the linear tetravalent peptide Km4G1 (3; see Table S2 and Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). Beyond revealing differences in affinities, the ITC results suggest that stoichiometric binding to GRFT becomes more costly if not impossible for constructs with short mannose spacing. Indeed, for both linear and branched displays, when mannose distances become too short, a distinct transition in the mode of binding is observed and > 1 glycopeptide per GRFT subunit is bound. A direct comparison between synthetic nonamannoside[8] (13) and natural Man9GlcNAc2Asn (14) showed that 13 and 14 bind GRFT with comparable affinities and stoichiometries (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Oligomannose mimetics. A) Schematic representations of glycopeptides. Amino acids, mannopyranose units, and linkers are defined in the legend. In the linear constructs, mannoses were appended to the side chains of lysine, ornithine, or diaminopropanoic acid. Abbreviations denote composition, where capital letters define amino acid type, and mn and Gn indicate the number of mannosylated amino acids and glycine residues, respectively. Bottom: chemical structures of B) nonamnannoside (13) and Man9GlcNAc2Asn (14), C) linear Km3G1 (2), and D) branched KG2K2m4 (11).

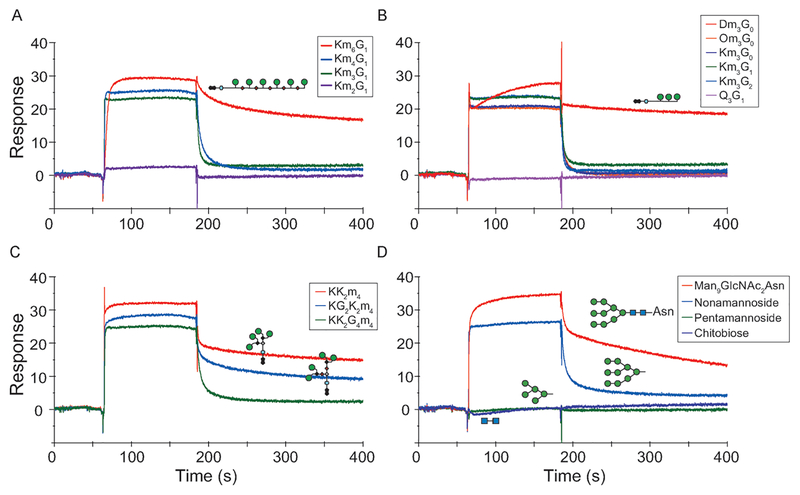

To further investigate the distinct binding transitions that occur as a function of valency and spacing we used SPR to obtain kinetic parameters (see the Supporting Information). The Kd values obtained by SPR were in very good agreement with those obtained by ITC (see Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). Representative sensorgrams for the three classes of glycopeptides binding to immobilized GRFT appear in Figure 2A–C and Figure S7 in the Supporting Information. Striking differences were observed when comparing Km6G1 (4) to its homologues of lower mannose valency 1–3 (Figure 2A). Km6G1 dissociates from GRFT at a significantly slower rate than Km3G1 and Km4G1 (2, 3), while Km2G1 gives the weakest response of any of the glycopeptides.

Figure 2.

SPR analysis of 1–14 binding to immobilized GRFT. Sensorgrams comparing the binding ofA) linear peptides with various mannose valencies, B) trivalent glycopeptides, C) tetravalent branched glycopeptides with various mannose spacings, and D) Man-9 derivatives. Negligible binding of pentamannoside and chitobiose to GRFT was observed. Experiments were run in triplicate. See Figures S5 and S6 in the Supporting Information for sensorgrams and Langmuir curves.

Differences in the kinetics of binding were also observed within the trivalent and branched series. Among the trivalent mimetics, all but Dm3G0 (8) bind GRFT with very fast equilibrium association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates. Dm3G0, which has the smallest distance between mannoses, displays by far the slowest dissociation rate from GRFT (Figure 2B). Similarly among the branched tetravalent constructs, 10 and 11, which contain closely spaced mannose pairs, exhibit slower kon rates and very slow koff rates relative to 12, which has the largest mannose spacing (Figure 2C). Importantly, the slow koff rates observed for 10 and 11 recapitulated the binding of Man9GlcNAc2Asn to GRFT (Figure 2d), and 14 showed a slower koff rate than nonamannoside 13.

SPR and ITC data show that different modes of GRFT binding occur depending on the mannose valency and proximity. To determine how they are engaging GRFT we used NMR spectroscopy to map the binding sites of representative ligands on GRFT and to detect the mode of binding by changes in signal intensities.

Glycopeptides were titrated to 15N-labeled GRFT and 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded for each sample.[6c] Changes in the signal intensities relative to unbound GRFT were plotted as a function of amino acid residue (see the Supporting Information).[6c] Data for three glycopep-tides that show either strong affinity for GRFT by ITC or very slow koff rates by SPR are presented in Figure 3. For high-affinity glyco-peptide Om3G0 (7), changes in cross-peak intensity are observed only for residues located in the mannose-binding pockets (Figure 3A). Together with ITC and SPR, the NMR data show that all three mannose residues in Om3G0 engage all three binding sites on one GRFT subunit to form a 1:1 complex, consistent with face-to-face binding. Similar behavior is seen for trivalent constructs Km3G2, Km3G1, and Km3G0 (see Figure S8 in the Supporting Information). In contrast, the step plot for hexavalent Km6G1 (Figure 3B) shows that the intensity of all the GRFT residues decreases uniformly with each addition of 4, thus indicating that binding to Km6G1 leads to formation of very large oligomers that are invisible by NMR spectroscopy. For oligomerization to occur, intermolecular cross-linking must be taking place. Given that all the resonance intensities diminish uniformly, binding and oligomerization must occur simultaneously.

Figure 3.

NMR spectroscopy and AUC reveal discrete modes of glycopeptide binding. Top: changes in signal intensities (y axis) as a function of amino acid residue observed in 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra of GRFT during titration with A) 7 (Om3G0), B) 4 (Km6G1), C) 11 (KG2K2m4), and D) Man9GlcNAc2Asn. Mannose binding sites are shown below. E) Expansions of sedimentation velocity data for GRFT (blue) or GRFT plus one (red) or two (green) equivalents of ligand. Single migrating species are observed for GRFT alone or in the presence of 7, while higher molecular weight species are observed for GRFT in the presence of 4, 11, and 14. See the Supporting Information for full plots. F) Surface representation of GRFT showing the binding surfaces of KG2K2m4 (left) and Man9GlcNAc2Asn (right) determined by NMR spectroscopy. Surfaces are colored by the change in signal volume of each residue, with the darker the color the greater the change. Mannoses from the crystal structure (Protein Data Bank accession number 2GUD) are represented in black sticks and highlight the binding site.

However, a different binding profile is seen in the step plot of branched KG2K2m4 (Figure 3c). Upon addition of 11, changes in all three mannose binding sites are apparent, and to a lesser degree a decrease in signal intensity for all the GRFT residues is observed. Remarkably, the NMR titration data for Man9GlcNAc2Asn appeared most similar to branched mimetic 11, where addition of Man-9 led to an overall decrease in the signals, with the resonances of the carbohydrate binding site diminishing to a greater extent (Figure 3D). These results indicate that for branched displays, whether synthetic as in 11 or for Man-9, GRFT binding must occur through a combination of binding modes—the decrease in signals for all three carbohydrate-binding sites shows that the mannose units can occupy any of the three mannose-binding sites, while the overall decrease in the signal intensities indicates that intermolecular protein–ligand cross-linking is taking place. Consistent with the shared GRFT binding modes of 11 and 14, mapping of the spectral changes onto a surface representation of GRFT shows nearly identical binding interfaces (Figure 3E).

To confirm the formation of aggregates, we used analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) to compare the sedimentation velocities of GRFT in the presence or absence of Om3G0, Km6G1, KG2K2m4, and Man9GlcNAc2Asn (Figure 3E and see Figure S9 in the Supporting Information). Those data show that in the absence of any glycopeptide, GRFT exists as a single species. Similarly, the addition of Om3G0 results in a single species that migrates slightly faster than dimeric GRFT, consistent with a face-to-face interaction and no aggregation. The addition of Km6G1 leads to a significant proportion of GRFT aggregates larger than the dimer, in agreement with the formation of aggregates observed by NMR spectroscopy. Interestingly, for KG2K2m4, a species corresponding to the GRFT–KG2K2m4 complex along with faster sedimenting species are observed, and are in fast exchange with one another. In the case of Man9GlcNAc2Asn, the formation of a tetrameric species is observed on addition of one equivalent, and the size of aggregates increases with additional equivalents of glycan.

The ultimate goal of this work was to create a synthetic Man-9 surrogate that recapitulates all aspects of binding to the potent antiviral lectin GRFT. The data provided by NMR spectroscopy, ITC, AUC, and SPR unambiguously reveal distinct modes of binding for different scaffolds and show that binding modes are sharply dictated by mannose spacing and valency. While multivalent scaffolds with large mannose spacing can bind in a face-to-face manner with the mannose units engaging all three binding sites on each GRFT subunit (n = 1, see Figure S10 in the Supporting Information), this is impossible for constructs with more closely spaced mannoses (exemplified in 8, 10, 11, and Man-9). Instead, our results demonstrate that when adjacent mannose spacing is restricted, distal mannoses engage the mannose-binding sites on one GRFT subunit and the more proximal mannose interacts with a second molecule of GRFT (see Figure S10 in the Supporting Information). This intermolecular binding model is consistent with our experimental data, and explains the stoichiometries of binding for mimetics and glycans containing this arrangement, the intermolecular cross-linking and oligomerization observed by NMR spectroscopy, and the slow koff rates revealed by SPR. We were surprised to find that occupation of all three binding sites leads to the highest affinity interactions, as this is not the mode in which high-mannose oligosaccharides bind GRFT. Our data suggest that each of the features that define Man-9, including the distance between the three arms, the valency, and conformations that must be imparted by the presence of the GlcNAc2 core, lead to two of the arms of Man-9 binding to one GRFT, and the remaining arm/s binding to a separate molecule of GRFT. This is consistent with the crystallographic analysis of a GRFT monomer bound to a synthetic nonamannoside. In that study, separate arms of the nonamannoside were complexed to two different GRFT monomers, which is the basis for inducing cross-linking.[9] Lastly, given the approximate 24 N-glycosylation sites on gp120 with most containing high mannose oligosaccharides, it is likely that the mechanisms revealed here also reflect the interactions between GRFT and the surface of gp120 that result in long residence times for GRFT bound to the viral protein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Lloyd for HRMS data, R. O’Connor for NMR support, and L.-X. Wang and C. Toonstra for Man-9. This work was supported by the AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program, Office of the Director, NIH (C.A.B.), and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIDDK).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201500157.

Contributor Information

Sabrina Lusvarghi, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD 20892 (USA).

Rodolfo Ghirlando, Laboratory of Molecular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD 20892 (USA).

Chi-Huey Wong, The Genomics Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, 128 Academia Road, Section 2, Nankang, Taipei 115 (Taiwan).

Carole A. Bewley, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD 20892 (USA).

References

- [1].Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, et al. , Essentials of Glycobiology, 2 ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a)Bonomelli C, Doores KJ, Dunlop DC, Thaney V, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN, PLoS One 2011, 6, e23521; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen PC, Chuang PK, Chen CH, Chan YT, Chen JR, Lin SW, Ma C, Hsu TL, Wong CH, ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 9, 1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a)Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, Stanfield RL, Julien JP, Ramos A, Crispin M, et al. , Science 2011, 334, 1097–1103; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, Louder R, Pejchal R, Sastry M, Dai K, et al. , Nature 2011, 480, 336–343; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Balzarini J, Lancet Infect. Dis 2005, 5, 726–731; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Balzarini J, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2007, 5, 583–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barton C, Kouokam JC, Lasnik AB, Foreman O, Cambon A,Brock G, Montefiori DC, Vojdani F, McCormick AA, OÏKeefe BR, et al. , Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a)Dam TK, Gerken TA, Brewer CF, Biochemistry 2009, 48, 3822–3827; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Godula K, Bertozzi CR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 15732–15742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a)Ziýłkowska NE, OÏKeefe BR, Mori T, Zhu C, Giomarelli B, Vojdani F, Palmer KE, McMahon JB, Wlodawer A, Structure 2006, 14, 1127–1135; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mori T, OÏKeefe BR, Sowder RC, Bringans S, Gardella R, Berg S, Cochran P, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW Jr., McMahon JB, et al. , J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 9345–9353; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Xue J, Gao Y, Hoorelbeke B, Kagiampakis I, Zhao B, Demeler B, Balzarini J, LiWang PJ, Mol. Pharm 2012, 9, 2613–2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a)Greatrex BW, Brodie SJ, Furneaux RH, Hook SM, McBurney WT, Painter GF, Rades T, Rendle PM, Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 2939–2950; [Google Scholar]; b) Cheaib R, Listkowski A, Chambert S, Doutheau A, Queneau Y, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 1919–1933. [Google Scholar]

- [8].a)Lee HK, Scanlan CN, Huang CY, Chang AY, Calarese DA, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Wong CH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 1000–1003; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 1018–1021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang SK, Liang PH, Astronomo RD, Hsu TL, Hsieh SL, Burton DR, Wong CH, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3690–3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Moulaei T, Shenoy SR, Giomarelli B, Thomas C, McMahon JB, Dauter Z, OÏKeefe BR, Wlodawer A, Structure 2010, 18, 1104–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.