Abstract

Background:

Elective delivery prior to 39 weeks, low-risk cesarean delivery, and episiotomy are routinely reported obstetric quality measures and have been the focus of quality improvement initiatives over the past decade.

Objective:

To estimate trends and differences in obstetric quality measures by race/ethnicity.

Research Design:

We used 2008–2014 linked birth certificate-hospital discharge data from New York City to measure elective delivery prior to 39 gestational weeks (ED<39), low-risk cesarean, and episiotomy by race/ethnicity. Measures were following the Joint Commission and National Quality Forum specifications. Average annual percent change (AAPC) was estimated using Poisson regression for each measure by race/ethnicity. Risk differences (RD) for non-Hispanic (NH) black women, Hispanic women, and Asian women compared to non-Hispanic (NH) white women were calculated.

Results:

ED<39 decreased among whites (AAPC = −2.7, 95%CI= −3.7, −1.7), while it increased among blacks (AAPC=1.3, 95%CI= 0.1, 2.6) and Hispanics (AAPC=2.4, 95%CI= 1.4, 3.4). Low-risk cesarean decreased among whites (AAPC= −2.8, 95C%CI= −4.6, −1.0), and episiotomy decreased among all groups. In 2008, white women had higher risk of most measures, but by 2014 incidence of ED<39 was increased among Hispanics (RD=2 per 100 deliveries, 95%CI=2, 4) and low-risk cesarean was increased among blacks (RD=3 per 100, 95%CI=0.5, 6), compared to whites. Incidence of episiotomy was lower among blacks and Hispanics than whites, and higher among Asian women throughout the study period.

Conclusion:

Existing measures do not adequately assess health care disparities due to modest risk differences; nonetheless, continued monitoring of trends is warranted to detect possible emergent disparities.

Keywords: Disparities, obstetrics, quality measurement

Introduction

Over the past decade, a focus on improving quality in obstetrics has brought about the introduction of guidelines and protocols for evidence-based care, the promotion of safety culture, and the auditing of adverse events.1 The development of quality measures that can be monitored over time by American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Joint Commission is an important component of these initiatives. Three measures on which quality initiatives have focused intensely are elective delivery prior to 39 weeks of gestation, low-risk cesarean delivery, and episiotomy.2–4 Each of these measures is based on substantial evidence of life course maternal and child morbidity at the individual level. For example, elective delivery prior to 39 weeks has been associated with higher risk of respiratory morbidity and neonatal intensive care unit admission in the newborn,5 and low-risk cesarean delivery has been linked with increased maternal length of stay, increased maternal infections, and adverse reproductive outcomes in subsequent pregnancies for primary cesarean deliveries.6 Routine episiotomy can lead to increased wound complications and severe perineal trauma.7 Quality improvement initiatives addressing these important outcomes are promising. However, one limitation of current obstetric quality measures that we previously identified is a lack of correlation with maternal and infant outcomes at the hospital level, suggesting they only measure a limited dimension of quality of care. The result is a lack of construct validity, or ability to measure the desired underlying construct of hospital quality.8, 9 We propose a second limitation is a lack of construct validity for the purpose of monitoring racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric care.

Substantial racial/ethnic disparities in maternal and infant outcomes are well-documented, and evidence suggests that quality of care may play a role in these disparities.10–12 A growing concern is that the current quality improvement initiatives, and the measures developed to guide them, may not address the wide racial and ethnic disparities observed in obstetric outcomes at the population level.8 We tested the validity of obstetric quality measures to monitor racial/ethnic disparities by examining 1)trends in quality measures by race/ethnicity, and 2) the magnitude of difference in measures between racial/ethnic groups. The measures tested were elective delivery prior to 39 weeks, low-risk cesarean delivery, and episiotomy.. Our approach was based on the on the assertion that quality measures with good validity to measure the underlying construct of health care disparities would indicate differences and trends in which racial/ethnic minorities have worse outcomes than white women. To examine these questions we used population-based linked birth certificate and hospital discharge data from New York City from 2008–2014.

Methods

Study Sample

The New York State Department of Health linked New York City birth certificate data to New York State Hospitalization data (SPARCS) for the years 2008 to 2014. Each birth record was linked to the hospital discharge record for the corresponding delivery, representing 836,309 deliveries. The sample size per year was: 2008 n=12,264, 2009 n=122,210, 2010 n=120,443, 2011 n=119,033, 2012 n=119,525, 2013 n=11,522, 2014 n=117,226. After excluding those with “other” or missing race the total sample size for analysis was 818, 356. We received Institutional Review Board approval from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and the New York State Department of Health.

Maternal Covariates

We obtained demographic information from the birth certificate data. We created five categories of race/ethnicity from mother’s self-reported race and Hispanic ancestry: Non-Hispanic black (black), Hispanic, non-Hispanic white (white), Asian and Other. We obtained information on obstetric factors from the birth certificate including clinical estimate of gestational age at delivery, plurality (single, twins, etc.), parity (number of previous live births), prior cesarean delivery, and vertex (head-first) presentation. All other obstetric and medical factors were obtained from the hospital discharge record using ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes. As described further below, information on select maternal morbidities and obstetric characteristics were also obtained from the birth certificate.

Quality Measures

We followed predefined algorithms for all quality measures without additional covariate adjustment because our goal was to evaluate existing quality measures for sensitivity to racial-ethnic disparities. We used algorithms defined in the Joint Commission Manual 2014A1 to determine elective delivery prior to 39 weeks and low-risk cesarean.13 The Joint Commission selected these measures in 2009, and hospitals began collecting data on the measures with April 1, 2010 discharges. The Joint Commission defines the numerator of the measure “elective delivery prior to 39 weeks” as patients with an ICD-9 code indicating medical induction of labor or cesarean delivery if not in labor, no rupture of the membranes, and no history of prior uterine surgery. The Joint Commission defines the at-risk denominator as women delivering at least 37 and less than 39 completed weeks gestation, excluding women with an ICD-9 diagnosis code for a condition possibly justifying elective delivery, less than 8 years and greater than 65 years of age, length of stay greater than 120 days, or enrolled in clinical trials. The Joint Commission specifies administrative data and medical record review as data sources. A previous report comparing calculating the measure using hospital discharge data and medical record review found that using hospital discharge data alone resulted in an overestimate of the incidence of elective delivery <39 weeks due to inability to detect presence of labor and fewer exclusions of women for conditions justifying elective delivery.14 Therefore, we made several other exclusions to increase the validity of our measure. First, following Korst et al, we identified additional ICD-9 codes that may indicate the presence of labor.14 Second, because additional case identification using birth data may improve validity,15–17 we identified additional variables in the birth certificate data that indicated the presence of labor or maternal conditions possibly justifying elective delivery, including cesarean after trial of labor, rupture of membranes, precipitous labor, placental abruption, diabetes, and hypertensive disorders.

Low-risk cesarean was defined as the proportion of deliveries that were by cesarean among singleton vertex deliveries to nulliparous women at 37 or more weeks of gestation. We excluded women with ICD-9-CM codes that signify contraindications to vaginal deliveries.13 The goal of these inclusion and exclusion criteria, as specified by the Joint Commission, is to create a homogenous group of patients. Also specified by the Joint Commission, we standardized the measure for low-risk cesarean by 5-year age groups using the observed maternal age distribution in the entire sample.

Finally, we used an algorithm recommended by the National Quality Forum to define episiotomy, which they first endorsed as a consensus standard in 2008.18 The episiotomy indictor was defined as the proportion of vaginal deliveries for which an episiotomy was conducted, excluding deliveries in which shoulder dystocia of the infant was present.

Statistical Analysis

We examined sample characteristics by race/ethnicity for the years 2008–2014 combined. We calculated the cumulative incidence (here forth referred to as “incidence”) of each quality measure by year within each racial/ethnic group. We used Poisson regression to calculate the average annual percent change (AAPC) in each measure, both overall and by race/ethnicity.19 This summary measure was developed for the comparison of time trends among subgroups even if the annual rate of change is not constant within each subgroup. The AAPC of the number of events with an offset of log(at-risk denominator) was defined using the Poisson regression as AAPC = (eβ− 1) 100 and a 95% CI was calculated. We did not include additional covariates in the AAPC model, with the exception of age-adjustment for low-risk cesarean per specifications, because our objective was to calculate and evaluate measures as they are currently defined by the Joint Commission/ACOG. The current definitions are designed, in theory, to minimize confounding by indication by creating homogenous groups of patients using exclusion and inclusion criteria. Next, we examined disparities between black, Hispanic, and white women for each year of data. We used log binomial regression with log-binomial maximum likelihood estimators and a linear link function to calculate risk differences and 95% confidence intervals for each year and measure.20 As with the AAPC analyses, we did not adjust for additional covariates beyond what covariates are used for inclusion/exclusion criteria, because our intent was to test the measures as current operationalized to monitor hospital quality. We chose difference measures because they are favored for population health monitoring of health care disparities, as they take into account the magnitude of the incidence of outcome in the population sub-groups.

Results

Sample characteristics for all women who gave birth in New York City from 2008–2014 by race/ethnicity are shown in Table 1. Black and Hispanic women were younger and more likely to be obese and have had previous live births. White women were most likely to have education beyond high school and to have private insurance. Asian women were the most likely to be foreign-born. All differences were statistically significant (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by race/ethnicity, New York City, 2008–2014

| Non-Hispanic Black n(%) |

Hispanic n(%) |

Non-Hispanic White n(%) |

Asian n(%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 174991 (100.0) | 252920 (100.0) | 257612 (100.0) | 132833 (100.0) |

| Mother’s age | ||||

| <20 | 13687 (7.8) | 24893 (9.8) | 3423 (1.3) | 1295 (1.0) |

| 20–34 | 126683 (72.4) | 188960 (74.7) | 178055 (69.1) | 100695 (75.8) |

| 35–39 | 25886 (14.8) | 30677 (12.1) | 58275 (22.6) | 24788 (18.7) |

| 40–44 | 8025 (4.6) | 7913 (3.1) | 16286 (6.3) | 5617 (4.2) |

| 45 or more | 710 (0.4) | 477 (0.2) | 1573 (0.6) | 438 (0.3) |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| Less than high school | 37283 (21.3) | 95591 (37.8) | 20727 (8.1) | 31337 (23.6) |

| High school | 47723 (27.3) | 61482 (24.3) | 49044 (19.0) | 24968 (18.8) |

|

Some colleague or Associate’s degree |

55661 (31.8) | 62332 (24.6) | 39527 (15.3) | 21095 (15.9) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 222479 (12.9) | 22328 (8.8) | 73628 (28.6) | 32195 (24.2) |

| Graduate degree | 10817 (6.2) | 10498 (4.2) | 73988 (28.7) | 23111 (17.4) |

| Missing | 1028 (0.6) | 689 (0.3) | 698 (0.3) | 127 (0.1) |

| Mother’s insurance | ||||

| Medicaid | 122667 (70.1) | 198028 (78.3) | 86137 (33.4) | 80348 (60.5) |

| Private | 43946 (25.1) | 48656 (19.2) | 167868 (65.2) | 50504 (38.0) |

| Uninsured | 4886 (2.8) | 3508 (1.4) | 1608 (0.6) | 1093 (0.8) |

| Other | 3492 (2.0) | 2728 (1.1) | 1999 (0.8) | 888 (0.7) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 6116 (3.3) | 8065 (3.2) | 15353 (6.0) | 15665 (11.9) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 66340 (38.5) | 114558 (45.9) | 169882 (66.4) | 89135 (67.4) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 50674 (29.4) | 74009 (29.6) | 46635 (18.2) | 20705 (15.7) |

| Obese (30.0–39.9) | 41200 (23.9) | 46556 (18.6) | 21351 (8.3) | 6413 (4.9) |

| Morbid Obesity (≥40) | 8171 (4.7) | 6511 (2.6) | 2646 (1.0) | 329 (0.3) |

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 78422 (44.9) | 107031 (42.4) | 123723 (48.1) | 67705 (51.0) |

| Multiparous | 96298 (55.1) | 145662 (57.6) | 133678 (51.9) | 65040 (49.0) |

| Nativity | ||||

| US-born | 100949 (57.7) | 114377 (55.2) | 186761 (72.5) | 31734 (23.9) |

| Foreign-born | 74042 (42.3) | 138543 (54.8) | 70851 (27.5) | 101099 (76.1) |

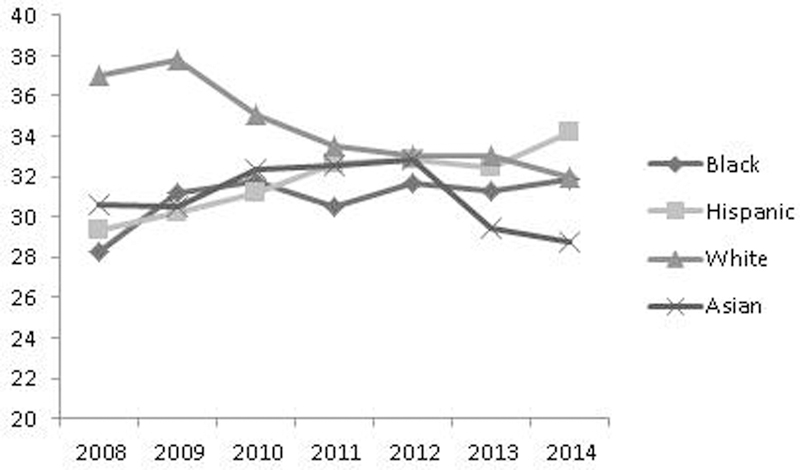

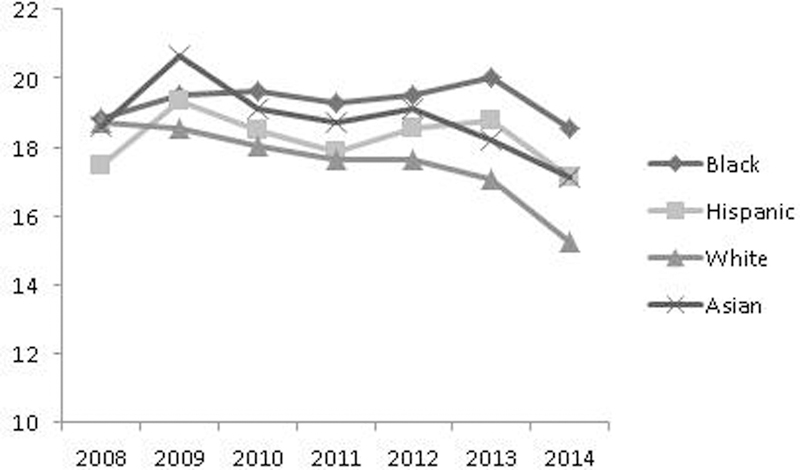

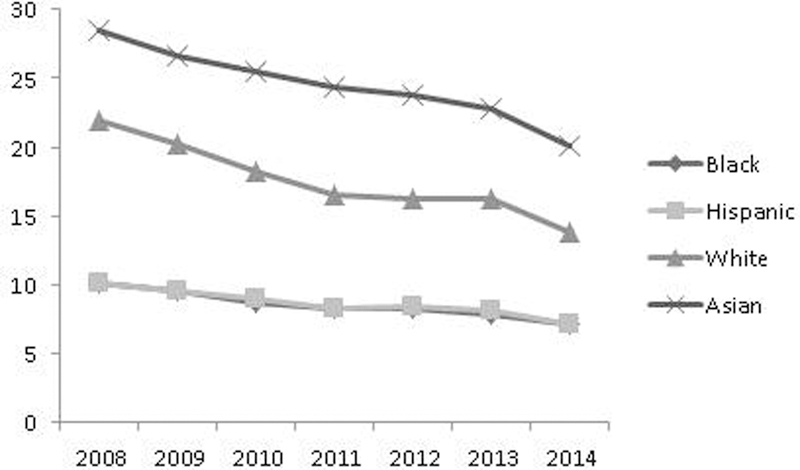

Time trends in obstetric quality measures and the results of the AAPC analysis are displayed graphically in Figures 1, 2 and 3. From 2008 to 2014, elective delivery < 39 weeks decreased among white women only (average annual average percent change (AAPC) = −2.7 (95%Confidence Interval (CI))= −3.7, −1.8) (Figure 1). Elective delivery <39 weeks increased among black (AAPC= 1.3, 95%CI=0.1, 2.6) and Hispanic women (AAPC=2.4, 95%CI=1.4, 3.4). Low risk cesarean decreased primarily among white women, with an AAPC of −3.8 (95%CI=−4.6, −1.0). Episiotomy decreased in all racial and ethnic groups (Figure 3). The AAPC was lowest in Hispanic women (AAPC= −4.9, 95%CI=−5.7, −4.2) and highest in white women (AAPC= −6.6, 95%CI= −6.9, −6.2).

Figure 1.

Percent elective delivery prior to 39 weeks by race/ethnicity, New York City, 2008–2014

Legend: Average Annual Percent Change for non-Hispanic blacks = 1.3 (95% Confidence Interval(CI)=0.1, 2.6); Hispanics = 2.4 (95% CI=1.4, 3.4); non-Hispanic whites = −2.7 (95% CI= −3.7, −1.8); Asians = −0.8 (95% CI=−2.1–0.6)

Figure 2.

Percent low-risk cesarean by race/ethnicity, New York City, 2008–2014

Legend: Average Annual Percent Change for non-Hispanic blacks = 0.1 (95% Confidence Interval(CI)= −2.3, 2.5); Hispanics = −0.34 (95% CI= −2.35– 1.72); non-Hispanic whites = −2.77 (95% CI= −4.55– −0.96); Asians = −1.75 (95% CI=−4.05– 0.60)

Figure 3.

Percent episiotomy by race/ethnicity, New York City, 2008–2014

Legend: Average Annual Percent Change for non-Hispanic blacks = −5.31 (95% Confidence Interval(CI)= −6.29– −4.33; Hispanics = −4.94 (95% CI= −5.73– −4.15); non-Hispanic whites = −6.57 (95% CI= −6.90– −6.23); Asians = −4.97 (95% CI=−5.62– −4.31)

Table 2 shows the absolute risk of each quality measure and risk differences for black, Hispanic, and Asian women compared to white women. In 2008, black and Hispanic women had a lower risk of elective delivery prior to 39 weeks than did white women (28 per 100 black women and 29 per 100 Hispanic women vs. 37 per 100 white women; risk difference (RD)= −9 per 100, 95%CI= −11, −7) and RD= −8 per 100, 95%CI= −10, −6). However, risk differences between the groups decreased each year. By 2014, there were no differences in risk between black and white women, with 32 per 100 elective deliveries in each group (RD= 0 per 100, 95%CI= −2, 2), and Hispanic women had a higher risk of delivery prior to 39 weeks than white women (Risk= 34 per 100, RD= 2 per 100, 95%CI=0, 4). Risk differences between Asian women and white women initially decreased over the study period, but then increased again, and in 2014 there were 29 per 100 cases of elective delivery <39 weeks (RD= 3 per 100,95%CI= −6, −1).

Table 2.

Absolute risk and risk differences (events per 100 deliveries) in obstetric quality measures by race/ethnicity and year, New York City, 2008–2014

| Year | Elective delivery <39 weeks | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Asian | White | |||||||

| n /100 |

RD* | 95%CI |

n /100 |

RD* | 95%CI |

n /100 |

RD* | 95%CI |

n /100 |

|

| 2008 | 28 | −9 | (−11, −7) | 29 | −8 | (−10, −6) | 31 | −6 | (−9, −4) | 37 |

| 2009 | 31 | −7 | (−9, −5) | 30 | −8 | (−9, −6) | 31 | −7 | (−10, −5) | 38 |

| 2010 | 32 | −3 | (−5, −1) | 31 | −4 | (−6, −2) | 32 | −3 | (−5, 0) | 35 |

| 2011 | 31 | −3 | (−5, −1) | 33 | −1 | (−3, 1) | 33 | −1 | (−3, 1) | 34 |

| 2012 | 32 | −1 | (−4, 1) | 33 | 0 | (−2, 2) | 33 | 0 | (−3, 2) | 33 |

| 2013 | 31 | −2 | (−4, 1) | 32 | −1 | (−3, 2) | 29 | −4 | (−6, −1) | 33 |

| 2014 | 32 | 0 | (−2, 2) | 34 | 2 | (0, 4) | 29 | −3 | (−6, −1) | 32 |

| Low-risk cesarean | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Asian | White | |||||||

|

n /100 |

RD† | 95%CI |

n /100 |

RD† | 95%CI |

n /100 |

RD* | 95%CI |

n /100 |

|

| 2008 | 19 | 0 | (−3, 3) | 18 | −1 | (−4, 1) | 19 | 0 | (−3, 3) | 19 |

| 2009 | 20 | 1 | (−2, 4) | 20 | 1 | (−2, 3) | 21 | 2 | (−1, 5) | 19 |

| 2010 | 20 | 2 | (−1, 4) | 18 | 0 | (−2, 3) | 19 | 1 | (−2, 4) | 18 |

| 2011 | 20 | 2 | (−1, 4) | 18 | 0 | (−2, 3) | 19 | 1 | (−2, 4) | 18 |

| 2012 | 20 | 2 | (−1, 5) | 19 | 1 | (−2, 3) | 19 | 1 | (−1, 4) | 18 |

| 2013 | 20 | 3 | (0, 6) | 19 | 2 | (0, 4) | 18 | 1 | (−1, 4) | 17 |

| 2014 | 18 | 3 | (0, 6) | 17 | 2 | (−1, 4) | 17 | 2 | (−1, 4) | 15 |

| Episiotomy | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Asian | White | |||||||

|

n /100 |

RD* | 95%CI |

n /100 |

RD† | 95%CI |

n /100 |

RD* | 95%CI |

n /100 |

|

| 2008 | 10 | −12 | (−12, −11) | 10 | −12 | (−12, −11) | 29 | 7 | (6, 8) | 22 |

| 2009 | 10 | −11 | (−11, −10) | 10 | −11 | (−11,−10) | 27 | 6 | (5, 7) | 21 |

| 2010 | 8 | −10 | (−10, −9) | 9 | −9 | (−10, −9) | 25 | 7 | (6, 8) | 18 |

| 2011 | 8 | −8 | (−9, −8) | 8 | −8 | (−9, −8) | 24 | 8 | (7, 9) | 16 |

| 2012 | 8 | −8 | (−9, −7) | 8 | −8 | (−8, −7) | 24 | 8 | (7, 8) | 16 |

| 2013 | 8 | −8 | (−9, −8) | 8 | −8 | (−9, −8) | 23 | 7 | (6, 7) | 16 |

| 2014 | 7 | −7 | (−7, −6) | 7 | −7 | (−7, −6) | 20 | 6 | (5, 7) | 14 |

Risk difference; non-Hispanic white is reference group

Risk difference; non-Hispanic white is reference group; age-adjusted in 5-year increments

Black women had a higher risk of low-risk cesarean delivery than white women throughout the study period, and the risk difference increased each year to reach a difference of 3 per 100 in 2014 (95%CI=1, 6) (Table 2). In that year, the low-risk cesarean delivery occurred in 18 per 100 black women and 15 per 100 white women. The Hispanic-white disparity in low-risk cesarean showed a similar trend, although differences were of smaller magnitude -- in 2014 there were 17 low risk cesarean deliveries per 100 Hispanic women, and the risk difference compared to white women was 2 per 100 (95%CI= −1, 4). Asian-white differences were also small and not statistically significant, and showed no notable trends (2014 risk difference = −2 per 100, 95%CI= −1, 4).

Black and Hispanic women consistently had a lower risk of episiotomy than white women (Table 2). For example, the risk difference between black women and white women was −12 per 100 in 2008 (95%CI= −12, −11) and −7 per 100 in 2014 (95%CI= −6, −7). Risk differences between Hispanic and white women were similar. Asian women had an increased risk of episiotomy throughout the study period, with absolute risk of 29 per 100 in 2008 and 20 per 100 in 2014. The risk difference compared to white women was stable over time. In 2008, the Asian-white risk difference was 7 per 100 (95%CI= 6, 8), and in 2014 it was 6 per 100 (95%CI=5, 7).

Discussion

In our analysis of NYC deliveries from 2008–2014, obstetric quality measures illustrated racial ethnic differences in trends over time, with a higher average rate of decrease for each measure among white women than among other racial/ethnic groups. At the beginning of the study period, black and Hispanic women had a decreased risk of elective delivery <39 weeks and similar risk of low-risk cesarean as white women. However, because of decreases in the incidence of these measures among white women only, by 2014 Hispanic women had higher incidence of elective delivery <39 weeks and black women had higher incidence of low-risk cesarean, although differences were of a modest magnitude. For the third measure, episiotomy, black and Hispanic women were at a decreased risk and Asian women at an increased risk compared with white women throughout the study period. Our findings of modest disparities in obstetric quality measures suggest these measures have weak validity for monitoring health care disparities. They also raise questions about why decreases in incidence in these quality measures were observed among NH whites but not among other racial/ethnic groups.

The data we present at the beginning of our study period on racial-ethnic differences are generally consistent with previous research that has raised concern about the validity of current obstetric quality measures to monitor health care disparities. Kozhimannil et al used similar linked birth certificate-hospital discharge data from 1995–2009 and found that black women were less likely to have a non-indicated induction prior to 39 weeks than white women but more likely to have a non-indicated cesarean delivery.21 Similarly, we found that in 2008 white women were more likely than black women to have an elective delivery prior to 39 weeks. However, our data demonstrate that by 2014 this disparity disappeared. Our findings regarding low-risk cesarean delivery differed slightly in that we did not find a disparity in 2008, but we did find that by 2014 black women had an excess risk of low-risk cesarean of 3 per 100 (95%CI=0, 6). Our finding that Asian women but not black and Hispanic women have a higher increased risk of episiotomy compared to non-Hispanic whites is also consistent with previous research.22, 23 We have added to this literature analyzing these disparities over time, in a period of intense quality improvement.

The most striking trends in obstetric quality measures observed over the study period were marked declines among white women, most likely due to decreases in the use of procedures for white women as promoted by aggressive quality improvement initiatives. The obstetric quality measures we examined are all overutilization or “overuse” measures, and may be less relevant for populations with poorer access to health care. Overuse is the provision of a medical procedure despite its risks outweighing the benefits for the patient.24 Overuse measures have only been associated with increased risk among racial/ethnic minorities in a narrow number of therapeutic areas.25 If overuse of obstetric interventions affects whites more than women from other racial/ethnic backgrounds, interventions targeting these measures might therefore logically show the greatest benefit among this group. Our findings that the magnitude of differences in obstetric overuse measures were modest and that measures declined primarily among NH whites highlight the limitation of overuse measures to monitor racial/ethnic disparities in health care.

Another interpretation of our findings is that recent obstetric quality initiatives are having a differential positive impact on patient subpopulations to the detriment of black and Hispanic women. Even if the divergent trends are primarily due to the fact white women are most affected by overuse of obstetric interventions, as described above, the hint of emerging disparities for elective delivery <39 weeks and low-risk cesarean could be a cause for concern. For example, an excess risk of 2 cases per 100 for elective delivery <39 weeks among Hispanic women and 3 cases per 100 for low-risk cesarean among black women emerged by 2014. The field of implementation science has shown that quality improvement interventions may differ in uptake and outcomes in different population groups, leading to varying effectiveness by subpopulation, which could explain the emergent excess risk.26 At the organizational level, common barriers to implementation of quality initiatives on maternity units are leaders’ and clinicians’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices, characteristics of the quality initiative, and the implementation climate, characterized as hospital resources and patient population.27 Implementation climate may be especially relevant to racial/ethnic disparities, although it is unclear if between hospital or within hospital differences in implementation climate would have a greater impact on the racial/ethnic differences in trends we observed.8 Regardless, the possibility that disparities could emerge after quality initiatives suggests that although the obstetric quality measures we tested are insufficient to monitor health care disparities, there is utility in examining the measures by racial/ethnic subgroup.

Differences and trends in population-level quality measures at the individual level may reflect differences and trends in hospital quality, given that the racial-ethnic distribution of hospitals differs. As such, practices of the hospital of delivery may explain (i.e. mediate) the differing trends we observed, and within any given hospital there may be no racial/ethnic differences in trends. However, we chose not to adjust for hospital of delivery in our analysis because we were interested in the magnitude of racial-ethnic disparities in quality measures at the population-level, including any differences that might result from site of care. Were we to have adjusted for hospital, it would mask the true population prevalence of each measure. Future research might explore hospital-level factors as an explanatory pathway for racial-ethnic differences in obstetric quality measures.

The differences in obstetric quality measures we reported may be due to residual dissimilarities in medical risk factors between racial/ethnic groups, such as obesity. We chose not to further risk-adjust our measures because we wanted to evaluate the performance of the measures specified by the Joint Commission and National Quality Forum. An advantage of our approach using trend analysis is that although racial/ethnic differences in medical risk factors may explain increased or decreased risk of a measure in any given year, these differences are unlikely to explain the substantial trends over time we identified, particularly in the low-risk patient populations these measures target. Additionally, for measures in which previous risk-adjusted analyses exist, our results are generally consistent. Two examples are an increased risk of cesarean among non-white groups and increased risk of episiotomy among Asian women.10, 22, 23, 28–35

One limitation of our analysis is that measuring elective delivery <39 weeks using hospital discharge data alone has been found to overestimate the incidence compared to chart review.14 In order to address this bias, we added exclusions using maternal morbidities ascertained by the birth certificate, although our measures are likely still overestimates of the true incidence. Our estimate of elective delivery <39 weeks is similar to other analyses in the literature that used linked birth certificate – hospital discharge data and the same low-risk denominator specified by the Joint Commission.14 Regardless of the magnitude of the estimate, it is important to note that even if the risk of a measure for any given year is an overestimate, if the sensitivity of the measure doesn’t vary with time, examination of trends can still provide useful information. A second limitation of the use of administrative data to ascertain quality measures is that trends in coding may differ systematically by hospital, and due to the unequal distribution of racial/ethnic groups by hospital, could bias our findings. Despite these known limitations to administrative data,36, they are an important source of data for population-based trends in health care disparities because hospital survey data on obstetric quality measures generally are not reported by any subpopulations such as race/ethnicity, nor are they usually of sufficient sample size to do so. Finally, New York City is a unique population and thus it is unclear the extent to which our results are generalizable to all US populations.

Conclusion

Our population-based study found that obstetric overuse quality measures were limited in their ability to monitor racial/ethnic disparities in health care, because the magnitude of disparities was modest. In a period of intense obstetric quality improvement initiatives, obstetric overuse quality measures declined in incidence most markedly for white women, suggesting the measures were most relevant for this group. However, given the possibility that quality initiatives may not be implemented successfully across hospitals or racial/ethnic groups, continued monitoring of current measures is warranted to detect possible emergent disparities. Nonetheless, additional obstetric quality measures are needed that better reflect racial and ethnic disparities in obstetric care.

Acknowledgments

Funding disclosure:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD068765 and by the National Institute of Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD007651. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Teresa Janevic, Departments of Population Health Science & Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York; Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Natalia N. Egorova, Departments of Population Health Science & Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Jennifer Zeitlin, Departments of Population Health Science & Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York; Inserm UMR 1153, Obstetrical, Perinatal and Pediatric Epidemiology Research Team (Epopé), Center for Epidemiology and Biostatistics Sorbonne Paris Cité, DHU Risks in pregnancy, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France.

Amy Balbierz, Departments of Population Health Science & Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Paul L. Hebert, Descartes University (Dr. Zeitlin), Paris, France, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington..

Elizabeth A. Howell, Departments of Population Health Science & Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York; Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

References

- 1.Pettker CM, Grobman WA. Obstetric safety and quality. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015;126:196–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashton DM. Elective delivery at less than 39 weeks. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2010;22:506–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viswanathan M, Hartmann K, Palmieri R, et al. The use of episiotomy in obstetrical care: a systematic review: summary 2005 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kozhimannil KB, Law MR, Virnig BA. Cesarean delivery rates vary tenfold among US hospitals; reducing variation may address quality and cost issues. Health Affairs 2013;32:527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh LI, Reddy UM, Männistö T, et al. Neonatal outcomes in early term birth. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2014;211:265. e261–265. e211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson S, Fleege L, Fridman M, et al. Morbidity following primary cesarean delivery in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:139 e131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth The Cochrane Library; 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell EA, Zeitlin J. Quality of Care and Disparities in Obstetrics. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 2017;44:13–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, et al. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. Jama 2014;312:1531–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obstetrics and gynecology 2015;125:1460–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, et al. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2016;214:122. e121–122. e127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis JM, Menard MK, Gee RE. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015;125:690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commission J. Specifications manual for Joint Commission national quality measures (v2014A1) 2015.

- 14.Korst LM, Fridman M, Estarziau M, et al. The Feasibility of Tracking Elective Deliveries Prior to 39 Gestational Weeks: Lessons From Three California Projects. Maternal and child health journal 2015;19:2128–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lydon-Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Cárdenas V, et al. The reporting of pre-existing maternal medical conditions and complications of pregnancy on birth certificates and in hospital discharge data. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2005;193:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydon‐Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Nelson JC, et al. Accuracy of reporting maternal in‐hospital diagnoses and intrapartum procedures in Washington State linked birth records. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 2005;19:460–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lain SJ, Hadfield RM, Raynes-Greenow CH, et al. Quality of data in perinatal population health databases: a systematic review. Medical care 2012;50:e7–e20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Main EK. New perinatal quality measures from the National Quality Forum, the Joint Commission and the Leapfrog Group. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;21:532–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, et al. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Statistics in medicine 2009;28:3670–3682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. American journal of epidemiology 2005;162:199–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozhimannil KB, Macheras M, Lorch SA. Trends in childbirth before 39 weeks’ gestation without medical indication. Medical care 2014;52:649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuilon A, Le Ray C, Prunet C, et al. Episiotomy in France in 2010: Variations according to obstetrical context and place of birth. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction 2016;45:691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Prendergast E, et al. Variation in and factors associated with use of episiotomy. Jama 2015;313:197–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korenstein D, Falk R, Howell EA, et al. Overuse of health care services in the United States: an understudied problem. Archives of internal medicine 2012;172:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kressin NR, Groeneveld PW. Race/Ethnicity and overuse of care: a systematic review. Milbank Quarterly 2015;93:112–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purnell TS, Calhoun EA, Golden SH, et al. Achieving health equity: closing the gaps in health care disparities, interventions, and research. Health Affairs 2016;35:1410–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bingham D, Main EK. Effective implementation strategies and tactics for leading change on maternity units. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing 2010;24:32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aron DC, Gordon HS, DiGiuseppe DL, et al. Variations in risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rates according to race and health insurance. Medical Care 2000;38:35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braveman P, Egerter S, Edmonston F, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of cesarean delivery, California. American Journal of Public Health 1995;85:625–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant AS, Washington S, Kuppermann M, et al. Quality and equality in obstetric care: racial and ethnic differences in caesarean section delivery rates. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 2009;23:454–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung JH, Garite TJ, Kirk AM, et al. Intrinsic racial differences in the risk of cesarean delivery are not explained by differences in caregivers or hospital site of delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2006;194:1323–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huesch M, Doctor JN. Factors associated with increased cesarean risk among African American women: Evidence from California, 2010. American journal of public health 2015;105:956–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irwin DE, Savitz DA, Bowes WA, et al. Race, age, and cesarean delivery in a military population. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1996;88:530–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janevic T, Loftfield E, Savitz D, et al. Disparities in cesarean delivery by ethnicity and nativity in New York City. Maternal and child health journal 2014;18:250–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabir AA, Pridjian G, Steinmann WC, et al. Racial differences in cesareans: an analysis of US 2001 National Inpatient Sample Data. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2005;105:710–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simas TAM, Magee BD, Delpapa E. Doing the Best With What We Have: We Need Better: Informing Obstetric Policy With Administrative Data LWW; 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]