Abstract

HPV vaccination rates in Florida are low. To increase rates, the CDC recommends clinics adhere to components of their evidence-based quality improvement program, AFIX (Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange of information). We explored factors associated with engaging in HPV-specific AFIX-related activities. In 2016, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of 770 pediatric and family medicine physicians in Florida and assessed vaccination practices, clinic characteristics, and HPV-related knowledge. Data were analyzed in 2017. The primary outcome was whether physicians’ clinics engaged in ≥1 AFIX activity. We stratified by physician specialty and developed multivariable models using a backward selection approach. Of the participants in analytic sample (n=340), 52% were male, 60% were White of any ethnicity, and 55% were non-Hispanic. Pediatricians and family medicine physicians differed on: years practicing medicine (p<0.001), HPV-related knowledge (p<0.001), and VFC provider status (p<0.001), among others. Only 39% of physicians reported engaging in ≥1 AFIX activity. In the stratified multivariable model for pediatricians, AFIX activity was significantly associated with HPV-related knowledge (aOR=1.33;95%CI=1.08–1.63) and provider use of vaccine reminder prompts (aOR=3.61;95%CI=1.02–12.77). For family medicine physicians, HPV-related knowledge was significant (aOR=1.57;95%CI=1.20–2.05) as was majority race of patient population (non-Hispanic White vs. Other: aOR=3.02;95%CI=1.08–8.43), daily patient load (<20 vs. 20–24: aOR=9.05;95%CI=2.72–30.10), and vaccine administration to male patients (aOR=2.98;95%CI=1.11–8.02). Fewer than half of Florida pediatric and family medicine physicians engaged in any AFIX activities. Future interventions to increase AFIX engagement should focus on implementing and evaluating AFIX activities in groups identified as having low engagement in AFIX activities.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, vaccination, cancer vaccines, adolescent health services, vaccination promotion, immunization programs, quality improvement programs

Introduction

Over 79 million people in the U.S. are currently infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), a virus that causes cervical, vaginal, vulvar, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers as well as genital warts.1 The nine-valent vaccine has the potential to prevent up to 90% of cervical cancers and 90% of genital warts.2 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends two doses of the HPV vaccine for males and females ages 9–14 or three doses for males and females 15–26.3 Despite the potential benefits of the vaccine and the ACIP recommendations, uptake remains disappointingly low with only 49.5% of girls and 37.5% of boys in the U.S. between 13 and 17 years of age being up-to-date on their HPV vaccinations in 2016 based on current ACIP guidelines.4 Vaccination rates in Florida are even lower for both girls (46.4%) and boys (34.5%).4 This is particularly concerning because Florida also has some of the highest rates of HPV-related disease including oropharyngeal and cervical cancers.5

In an effort to increase pediatric vaccination rates, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created a quality improvement program: Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange of information (AFIX).6 AFIX is a widely accepted strategy for improving childhood vaccination rates7 and is a promising approach for increasing HPV vaccine coverage among adolescents.8 Additionally, recent data show healthcare providers who did receive an AFIX visit from the health department have positive attitudes with regard to these visits including high scores on ease of understanding, convenience, helpfulness, and facilitation.9 The AFIX approach incorporates four key strategies that have been shown to reliably improve providers’ immunization service delivery and raise vaccination coverage levels: (1) assessing the providers’ vaccination coverage levels; (2) giving the providers feedback of results of the assessment as well as strategies to improve vaccine delivery; (3) providing incentives to reward improved vaccination rates; and (4) exchanging information through continued follow-up with providers to both monitor and support progress.6 AFIX uses an “assessment and feedback” approach in which state and local health departments deliver vaccine quality improvement consultations to providers, with a particular focus on providers who are a part of the Vaccines for Children (VFC) federal low cost vaccination program.6 While AFIX encounters are usually administered by health departments to the clinics, the present study is extending the utilization of these quality improvement initiatives to examine provider-reported integration of the AFIX-based strategies specific to HPV vaccination in their clinics, regardless of whether an AFIX visit occurred in the clinic.

Previous research demonstrates that the use of AFIX-based strategies, such as informing providers of their vaccination coverage, increases vaccination rates.8,9 Therefore, the present study aimed to identify characteristics associated with low usage of these evidence-based strategies in order to identify potential targets for future interventions. The objective of the present study was to assess Florida primary care physicians’ report of HPV-specific quality improvement activities aligned with the CDC’s AFIX program and determine factors associated with use of AFIX to identify potential areas for future intervention efforts.

Methods

Sample

As part of an ongoing study assessing Florida-based primary care physicians’ experiences with HPV vaccination recommendation in clinical practice, we conducted two cross-sectional surveys of primary care physicians in Florida. Results of the first survey, completed in 2014, were focused on physician recommendation of HPV vaccination for adolescent and young adult boys, and have been previously published.10,11 Here we present results from the second survey, conducted in 2016 and analyzed in 2017, which was focused on identifying multi-level targets for intervention strategies to improve HPV vaccination rates. Specifically, identifying factors associated with low usage of HPV-specific AFIX-based strategies. The study received ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile, a database of all licensed U.S. physicians.12 We did not recruit physicians who: 1) were trainees, 2) were locum tenens, 3) reported their major professional activity was non-patient care, 4) were ≥65 years of age, as the AMA Masterfile has been shown to have a significant lag in updating retired physicians,13 and 5) listed a post office box for their address (precluding use of FedEx mailing). Florida-based pediatric and family medicine physicians were sampled based on their proportional representation in the Florida physician primary care workforce and randomly selected from the AMA Masterfile.11 We selected only one physician per group practice and if a provider indicated they did not provide care to either males or females between the ages of 9 and 26 they were excluded from analyses. This study was granted a waiver of documentation of informed consent based on the following criteria: 1) the only record linking the subject and the research is the consent document and the principal risk would be potential harm resulting from a breach of confidentiality; and 2) the research presents no more than minimal risk of harm to subjects and involves no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside of the research context.

Over the course of two months, our study team mailed one original and up to two reminder surveys to our sample. Physicians were given the option to either mail their completed paper survey back to our study team or respond via an online link included in the cover letter that accompanied the mailed survey. To increase our survey response rate, representatives from the Florida Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (FCAAP) and the Florida Academy of Family Physicians (FAFP) also sent two emails to their respective membership informing them about our study and the importance of their participation.

Measures

The survey was developed using previously validated items where possible.14–21 The final 41-item survey assessed three domains: physician characteristics, general clinic characteristics, and vaccine-specific characteristics. Physician characteristics included demographic information, specialty, state of residency training, and HPV knowledge. General clinic characteristics included practice size and location, and demographic characteristics of the patient population. Knowledge was measured using 11-items regarding HPV infection, disease, vaccination, and guidelines from various organizations (including the World Health Organization and ACIP). One point was awarded for each correct response and correct responses were summed to crease a knowledge score (range: 0–11). For a full list of variables assessed, see Table 1. Vaccine-specific characteristics included whether they administer the vaccine to male and female patients; are a VFC provider; whether they use reminder prompts and how many different prompts they use; and if they have a vaccine coordinator in their office.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of the Study Population Collected in Florida in 2016 (N=340)

| Physician characteristics | Total samplea (n=340) n (%); m (SD) |

Pediatricians (n=160) n (%); m (SD) |

Family Medicine (n=146) n (%); m (SD) |

p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.002 | |||

| Male | 171 (51.5) | 67 (42.1) | 85 (59.9) | |

| Female | 161 (48.5) | 92 (57.9) | 57 (40.1) | |

| Age | 0.332 | |||

| 30–44 | 66 (19.4) | 28 (18.1) | 35 (25.2) | |

| 45–54 | 108 (33.3) | 53 (34.2) | 43 (30.9) | |

| 55–64 | 150 (46.3) | 74 (47.7) | 61 (43.9) | |

| Race | 0.305 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 195 (59.6) | 89 (57.1) | 88 (62.0) | |

| Black/African American | 23 (7.0) | 9 (5.8) | 12 (8.5) | |

| Asian | 35 (10.7) | 23 (14.7) | 12 (8.5) | |

| Other | 74 (22.6) | 35 (22.4) | 30 (21.1) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.006 | |||

| Hispanic | 145 (44.9) | 81 (51.9) | 50 (36.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 178 (55.1) | 75 (48.1) | 89 (64.0) | |

| Years practicing medicine | <0.001 | |||

| 15 or fewer | 120 (37.7) | 39 (25.3) | 68 (51.5) | |

| 16–24 | 112 (35.2) | 58 (37.7) | 40 (30.3) | |

| 25 or more | 86 (27.0) | 57 (37.0) | 24 (18.2) | |

| State completed residency | 0.837 | |||

| Florida | 102 (31.8) | 51 (32.7) | 45 (33.8) | |

| Other | 219 (68.2) | 105 (67.3) | 88 (66.2) | |

| Clinical specialty | ||||

| Pediatrics | 160 (49.1) | |||

| Family Medicine | 146 (44.8) | |||

| Otherc | 20 (6.1) | |||

| HPV knowledge (range 0–11) | 4.2 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| General clinic characteristics | Total sample |

Pediatricians (n=160) n (%); m (SD) |

Family Medicine (n=146) n (%); m (SD) |

p-value |

| HPV-specific AFIX activities | 0.063 | |||

| No AFIX Activities | 206 (60.6) | 84 (52.5) | 92 (63.0) | |

| At least 1 AFIX Activity | 134 (39.4) | 76 (47.5) | 54 (37.0) | |

| Number of physicians | 0.143 | |||

| 1 | 105 (32.0) | 47 (29.7) | 52 (35.6) | |

| 2–5 | 48 (14.6) | 21 (13.3) | 24 (16.4) | |

| 6–15 | 162 (49.4) | 87 (55.1) | 63 (43.2) | |

| 16 or more | 13 (4.0) | 3 (1.9) | 7 (4.8) | |

| Clinic situation | 0.004 | |||

| Single specialty | 234 (70.9) | 125 (79.1) | 92 (64.3) | |

| Multi-specialty | 81 (24.5) | 31 (19.6) | 41 (28.7) | |

| Other | 15 (4.5) | 2 (1.3) | 10 (7.0) | |

| Clinic arrangement | 0.065 | |||

| Full or part owner | 170 (51.5) | 91 (58.0) | 68 (47.6) | |

|

Employee of physician- owned practice |

62 (18.8) | 34 (21.7) | 24 (16.8) | |

|

Employee of hospital/hospital system |

38 (11.5) | 11 (7.0) | 22 (15.4) | |

|

Employee of a group or HMO |

16 (4.8) | 7 (4.5) | 6 (4.2) | |

|

Employee of hospital, clinic, or university |

28 (8.5) | 10 (6.4) | 16 (11.2) | |

| Other | 16 (4.8) | 4 (2.5) | 7 (4.9) | |

| Clinic location | 0.282 | |||

| Urban | 178 (53.8) | 90 (57.3) | 69 (48.3) | |

| Suburban | 116 (35.0) | 51 (32.5) | 55 (38.5) | |

| Rural/Other | 37 (11.2) | 16 (10.2) | 19 (13.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity of patients | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 140 (42.4) | 49 (31.4) | 78 (54.5) | |

| Otherd | 190 (57.6) | 107 (68.6) | 65 (45.5) | |

| Typical daily patient load | <0.001 | |||

| Less than 20 | 99 (29.8) | 38 (24.1) | 48 (33.6) | |

| 20–24 | 93 (28.0) | 36 (22.8) | 51 (35.7) | |

| 25 or more | 140 (42.2) | 84 (53.2) | 44 (30.8) | |

| Use EMR? | 0.028 | |||

| Yes | 296 (88.4) | 133 (84.2) | 133 (92.4) | |

| No | 39 (11.6) | 25 (15.8) | 11 (7.6) | |

|

Vaccine specific characteristics |

Total sample |

Pediatricians (n=160) n (%); m (SD) |

Family Medicine (n=146) n (%); m (SD) |

p-value |

| Administer the HPV vaccine to males |

<0.001 | |||

| No | 113 (33.3) | 13 (8.1) | 76 (52.1) | |

| Yes | 226 (66.7) | 147 (91.9) | 70 (47.9) | |

| Administer the HPV vaccine to females |

<0.001 | |||

| No | 94 (27.6) | 9 (5.6) | 63 (43.2) | |

| Yes | 246 (72.4) | 151 (94.4) | 83 (56.8) | |

| VFC provider | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 176 (52.2) | 135 (84.9) | 34 (23.4) | |

| No | 138 (40.9) | 23 (14.5) | 93 (64.1) | |

| I don’t know | 23 (6.8) | 1 (0.6) | 18 (12.4) | |

| HPV reminder prompts used | 0.002 | |||

| Didn’t use any reminders | 98 (28.8) | 29 (18.1) | 51 (34.9) | |

| Used one reminder | 129 (37.9) | 63 (39.4) | 54 (37.0) | |

| Used more than 1 reminder | 113 (33.2) | 68 (42.5) | 41 (28.1) | |

| Have vaccine coordinator | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 243 (73.0) | 143 (90.5) | 85 (59.4) | |

| No | 81 (24.3) | 13 (8.2) | 54 (37.8) | |

| I don’t know | 9 (2.7) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.8) |

Abbreviations: HPV (human papillomavirus), AFIX (assessment, feedback, incentives, exchange of information), HMO (health maintenance organization), EMR (electronic medical record), VFC (vaccines for children)

Percentages in this column do not include missing data. Less than 6% of data on any given variable was missing.

p-value indicates the statistical difference between family medicine physicians and pediatricians

”Other” category for physician specialty includes: internal medicine, general practice, urgent care/emergency medicine, pediatric subspecialties, adult-only family medicine, allergy/immunology

”Other” category for patient race/ethnicity includes: Non-Hispanic Black (n=25), Hispanic (n=102), Native American/Alaska Native (n=2), other/multiracial (n=14), and no definable majority (n=47)

A series of questions assessed whether the physician’s clinic used AFIX-based strategies related to HPV vaccination, regardless of whether these activities were the result of a health department visit or not, with at least one question assessing each of the AFIX constructs. Assessment was the only construct assessed with two different questions. We asked physicians whether their clinic ever reviewed series initiation and completion for male or female patients. Separate questions assessed series initiation and completion. For Feedback, physicians indicated whether their clinic provided one-time feedback to health care providers regarding their HPV vaccination rates. We assessed Incentives by asking the physicians to indicate whether their clinic provided rewards based on improved HPV vaccination rates. Finally, eXchange of information was quantified by assessing whether the physicians were provided ongoing feedback on their HPV vaccination rates. Participants had the option of replying to each question with “yes,” “no,” or “unsure.” The two questions examining assessment, along with one question each for feedback, incentives, and exchange, resulted in five questions assessing AFIX-based strategies.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the responses to AFIX-related activities were examined for the total sample and then separately for family medicine physicians and pediatricians because preliminary analyses showed significant differences on several variables between these two specialties. For AFIX-based strategies, due to uneven responses, the sample was dichotomized into those who responded “yes” to any one of the five questions used to assess AFIX-related quality improvement strategies and those who engaged in none of the components. This was done because more than half of participants (60.6%) indicated they did not engage in any AFIX activities.

Differences in engagement in at least one AFIX-based strategy were examined by comparing pediatric and family medicine practitioners. Those with a specialty of “other” (n=20) were not analyzed due to the small sample. Finally, multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed for family medicine physicians and pediatricians separately to assess factors associated with engagement in AFIX-based strategies. We created a multivariable model using backward stepwise selection. In order to obtain the best fit model, a p-value of 0.1 was needed for a variable to remain in the final model. The initial models included the following variables: physician gender, physician age, physician race, physician ethnicity, years practicing medicine, residency location, knowledge score, number of physicians in the clinic, clinic situation, clinic arrangement, clinic location, patient population race/ethnicity, daily patient load (includes total number of patients the provider sees in one day), use of EMR, administer vaccine to males, administer vaccine to females, VFC provider status, use of reminder prompts, have a vaccine coordinator. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v24.

Results

Of the 770 surveys mailed and 46 were undeliverable resulting in 724 surveys being delivered to respondents. Of those, 367 were completed and returned to study staff. After accounting for 16 duplicate surveys, our overall response rate was 48.5% (351/724). We excluded participants who reported they did not provide care to male or female patients between the ages of 9 and 26 (n=8), who indicated their primary specialty was geriatrics (n=2), and returned the survey after the close of the data collection portion of the study (n=1), resulting in a final analytic sample size of 340. Given that the surveys were anonymous, we were unable to determine if there was a difference between responders and non-responders on demographic and clinic characteristics. However, we compared our analytic sample to the sample of physicians included in the initial recruitment mailings on age, gender, and specialty. We found no statistically significant difference between the analytic sample and recruited physicians by specialty (p=0.249). While the groups were statistically significantly different in age, the analytic sample was only marginally younger than the recruited sample (mean age=52.3 vs. 53.7; p=0.008), and the statistical difference was likely due to the large sample sizes. Additionally, a difference of only 1.4 years, in practical terms, would likely not indicate any training or generational differences between groups. Similarly, there was a higher proportion of men in the recruited sample (59.7%) as compared to the analytic sample (51.5%). Although statistically significant (p=0.012), this slight difference was unlikely to affect results. Furthermore, our previous studies have shown no differences in HPV vaccination attitudes by physician gender,11,14 further indicating this slight difference was unlikely to affect results.

Characteristics of the total sample, as well as differences between pediatricians and family medicine physicians, are presented in Table 1. Briefly, more than half of participants were male (52%), White (60%), and/or non-Hispanic (55%). The majority reported their specialty as either pediatrics (49%) or family medicine (45%), were VFC providers (52%), and completed their residency outside of Florida (68%). Many participants reported their clinic was located in an urban setting (54%), utilized electronic medical records (88%), and had a vaccine coordinator (73%). Despite nearly all participants identifying as either pediatricians or family medicine physicians and seeing patients 9–26 years old, 28% of physicians reported the HPV vaccine was not administered to female patients in their clinic and 33% indicated the HPV vaccine was not administered to male patients in their clinic.

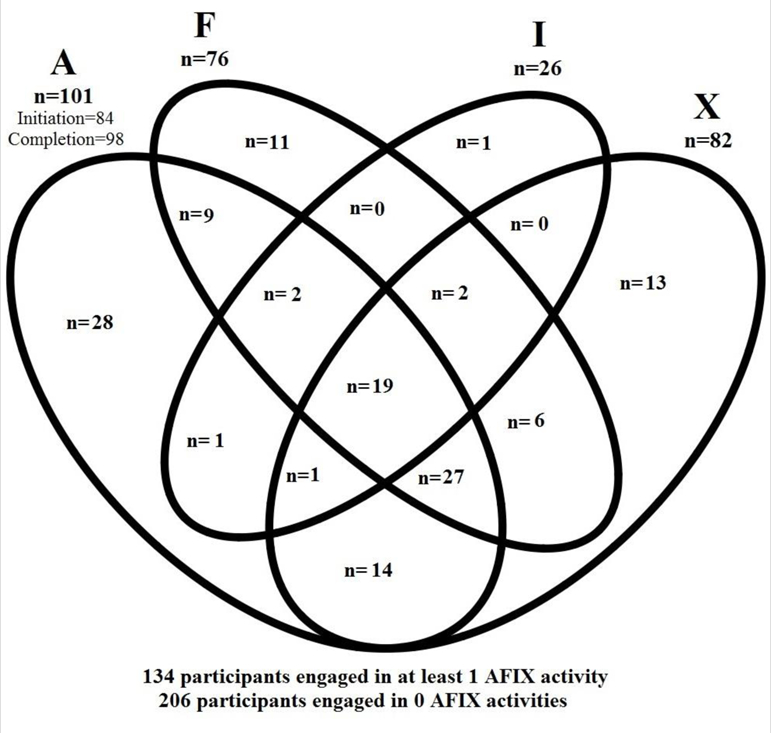

AFIX-related components, corresponding survey questions, frequency with which participants responded “yes” to the survey items, and differences by specialty are reported in Table 2. For a diagrammatic representation of the numbers of people responding “yes” to each AFIX-based activity, see the Venn diagram in Figure 1. A minority of physicians (n=134; 39%) reported that their clinic utilized at least one AFIX-based activity specific to HPV vaccines. Of the five activities assessed, only 19 participants (6%) reported engaging in all of them. A small proportion of respondents reported that their clinic had reviewed series initiation (25%) or series completion (29%) rates for either adolescent female or male patients. Twenty-two percent reported one-time feedback on HPV vaccination rates and 24% reported they were provided ongoing feedback on their HPV vaccination rates following implementation of quality improvement strategies. Of VFC providers, a group that is targeted for AFIX activities to support providers in increasing pediatric vaccination rates, only approximately half (97/176; 55%) indicated they engaged in at least one AFIX-related activity related to HPV vaccination. This is this is significantly different from the non-VFC providers, of whom, less than a quarter engaged in at least one AFIX-based activity (33/138; 23.9%) (p<0.001). There were not significant differences by specialty for most of the constructs; however, there was a statistically significant difference between family medicine physicians and pediatricians on whether they were provided ongoing feedback on their HPV vaccination rates (p<.0001).

Table 2:

AFIX Components and Corresponding Frequency of Participants Responding “Yes” to Each Survey Item (n=134)a

| CDC’s AFIX Components | Corresponding Survey Questions | Total n (%) of Participants Responding “Yes”b |

Pediatricians n (%) of Participants Responding “Yes” |

Family Medicine n (%) of Participants Responding “Yes” |

p- valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Has your practice ever done any of the following specific to HPV vaccination? (yes, no, unsure) |

|||||

|

Assessment of the healthcare provider’s vaccination coverage levels and immunization practices. |

Reviewed series initiation rates for either adolescent males or females |

84 (24.7) | 46 (28.8) | 36 (24.7) | 0.419 |

| Reviewed series completion rates for either adolescent males or females |

98 (28.8) | 57 (35.6) | 39 (26.7) | 0.093 | |

|

Feedback of results to the provider along with recommended quality improvement strategies to improve processes, immunization practices, and coverage levels. |

Provided one‐time feedback to health care providers regarding HPV vaccination rates |

76 (22.4) | 43 (26.9) | 31 (21.2) | 0.250 |

|

Incentives to recognize and reward improved performance. |

Provided rewards to providers based on improved HPV vaccination rates |

26 (7.6) | 14 (8.8) | 10 (6.8) | 0.537 |

| eXchange of information with providers to follow-up on their progress towards quality improvement in immunization services and improvement in immunization coverage levels. |

Provided ongoing feedback on their HPV vaccination rates after quality improvement strategies were implemented |

82 (24.1) | 56 (35.0) | 24 (16.4) | <0.001 |

|

Total responding “yes” to at least one of the above |

134 (39.4) | 76 (47.5) | 54 (37.0) | 0.063 |

Participants were excluded from the table if they indicated they did not engage in any AFIX-related activities (n=206)

The “total” column includes even those participants who indicated their specialty was “other” or missing.

p-value indicates the statistical difference between family medicine physicians and pediatricians

Figure 1.

Distribution of Participants Answering “Yes” to Engaging in Each Activity

Results from the multivariable analyses can be found in Table 3. For pediatricians, two variables were significantly associated with engagement in at least one AFIX-based strategy: (1) greater HPV-related knowledge (aOR=1.33; 95% CI=1.08–1.63); and (2) use of one reminder prompt (aOR=3.61; 95% CI=1.02–12.77) or more than one reminder prompt (aOR=6.59; 95% CI=1.86–23.37), compared to using no reminder prompts.

Table 3.

| Pediatricians Multivariable aOR (95% CI) (n=160) |

Family Medicine Multivariable aOR (95% CI) (n=146) |

|

|---|---|---|

| HPV knowledge (range 0–11) | 1.33 (1.08–1.63) | 1.57 (1.20–2.05) |

| Race of patients | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | (ref.) | |

| Other | 3.02 (1.08–8.43) | |

| Typical daily patient load | ||

| Less than 20 | (ref.) | |

| 20–24 | 9.05 (2.72–30.10) | |

| 25 or more | 1.66 (0.48–5.70) | |

| Administer the vaccine to males | ||

| No | (ref.) | |

| Yes | 2.98 (1.11–8.02) | |

| Reminder prompts used | ||

| Didn’t use any reminders | (ref.) | |

| Used one reminder | 3.61 (1.02–12.77) | |

| Used more than 1 reminder | 6.59 (1.86–23.37) |

The following variables were included as potential covariates for both models: physician gender, physician age, physician race, physician ethnicity, years practicing medicine, residency location, knowledge score, number of physicians in clinic, clinic situation, clinic arrangement, clinic location, patient population race/ethnicity, daily patient load, use of EMR, administer vaccine to males, administer vaccine to females, VFC provider status, use of reminder prompts, have a clinic vaccine coordinator.

For both models we used backward stepwise regression with a significance level of 0.1 to stay in the model.

For family medicine physicians, HPV-related knowledge also positively predicted AFIX-based activity (aOR=1.57; 95% CI=1.20–2.05). Other positive predictors were: (1) having a majority of patients not non-Hispanic White (aOR=3.02; 95% CI=1.08–8.43); (2) having a typical daily patient load of 20–24 patients/day as compared to less than 20/day (aOR=9.05; 95% CI=2.72–30.10); and (3) administering the HPV vaccine to males in their clinics (aOR=2.98; 95% CI=1.11–8.02).

Discussion

Increasing HPV vaccination rates is of particular importance in Florida, where HPV vaccine uptake falls below the national average for both boys and girls.4 Recent research has shown that using the evidence-based strategies related to AFIX-activities results in modest increases of HPV vaccine uptake.8,22,23 Despite the potential benefits of using AFIX-related quality improvement strategies, the majority of participants in our sample reported their clinic did not engage in any of the HPV-related AFIX-based activities we measured, even though the majority indicated they were VFC providers and should have participated in AFIX visits from the health department.

While engagement in AFIX-related quality improvement strategies was disappointingly low in our population, what was perhaps more striking were the rates of physicians who indicated they provided care to patients between the ages of 9 and 26, but did not HPV vaccine was not administered in their clinic. Indeed, one-third of participants indicated HPV vaccine was not administered to male patients in their clinic and over one-fourth of participants indicated it was not administered to female patients in their clinic. These low rates of vaccine administration are of particular concern. Future research should examine reasons behind this lack of HPV vaccine administration as well as possible interventions to increase administration to age-appropriate patients.

Pediatricians who do not utilize reminder prompts had lower odds of engaging in at least one HPV-related AFIX-based strategy which indicates a group that could be targeted for an intervention could be providers with less systems-level support for vaccinations, such as reminder systems. HPV-related knowledge was associated with HPV-related AFIX activity regardless of specialty and increasing HPV-related knowledge may be a viable means of increasing HPV vaccination itself. Additionally, our results indicated eXchange of information was the only construct that significantly differed between specialties. This may indicate that while pediatricians and family medicine physicians are receiving similar efforts for most of the AFIX-related quality improvement strategies, there is less emphasis in the long-term follow-up for family medicine. One possible explanation is that pediatric clinics account for the majority of general vaccinations administered24,25 and have more infrastructure for data monitoring programs including systems to track undervaccinated children.26 As with all of the variables, it is unclear what the temporal association is between HPV knowledge and AFIX-related activities. Longitudinal research is needed to elucidate the relationship between these factors.

This study is among the first to examine factors associated with HPV-related AFIX-based strategies and it has many strengths. For example, the study featured a randomly-selected, statewide sample and physicians’ report of their clinics’ participation in AFIX-related activities. However, the results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. The cross-sectional survey design precludes the ability to make causal inferences about variables significantly associated with AFIX-related activities. The participants surveyed were from a single state and therefore their responses may not be generalizable to the broader U.S. physician population. However, focusing on one state allowed us to examine AFIX-related activities in a state with relatively high rates of HPV-related disease and relatively low rates of HPV vaccination.4,5 Physicians may have reported socially-desirable responses regarding vaccination behaviors; however, the anonymous nature of the survey, as well as the range of responses we received, suggest social desirability was minimal. Physicians most in favor of HPV vaccination may have been more inclined to complete the survey, possibly providing an overestimate of the proportion engaging in AFIX-aligned quality improvement activities. This overestimation of AFIX-related activities in our study population serves to underscore the importance of the study findings because engagement in AFIX-related activities in a less engaged population is presumably even lower. We assessed physicians’ report of whether these HPV-related AFIX-based strategies were occurring in their clinic, but we did not assess organizational-level quality improvement strategies that may have been occurring and of which physicians may be unaware. Additionally, the physicians’ clinics may have engaged in AFIX-related activities that we did not assess, such as comparing HPV vaccination rates with other adolescent platform vaccines (meningococcal and Tdap [tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis]) to highlight missed opportunities in the clinic; however, we believe the activities assessed represent the core of the program. Because we selected one physician per clinic, there is the possibility the physician we chose did not have the same experience with AFIX-based strategies as other physicians in the same practice. However, by selecting only one physician per clinic we ensured non-violation of statistical assumptions pertaining to independence of responses. Finally, our study was limited to physicians, although other health care providers may recommend HPV vaccination. Thus, a study examining AFIX-related activities and HPV vaccination among other allied health professionals is warranted.

This study adds valuable information regarding HPV vaccination, engagement in AFIX activities, and factors associated with AFIX activities in order to identify areas for intervention. Future research should include qualitative research methods to better understand reasons why there is low utility of AFIX-based strategies. Additionally, future interventions to increase HPV vaccination should focus on implementing and evaluating AFIX-based strategies with groups that indicated low report of AFIX-related activities: family medicine physicians, physicians reporting low HPV-related knowledge, and those who do not have vaccine reminder systems in their office.

Highlights:

The AFIX program uses evidence-based strategies to increase childhood vaccinations.

Engagement in HPV-specific AFIX activities was low in this population.

This study identified factors associated with engagement in HPV-related AFIX activities.

Understanding these factors helps to target populations for future interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The content of this research is solely the responsibility of the authors. This research was supported by funding from the Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program (4BB10). This work was also supported in part by the Biostatistics Core at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292). The efforts of Drs. Kasting and Christy are supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R25- CA090314). Dr. Kasting is additionally supported by the Center for Research in Infection and Cancer (K05-CA181320).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this topic to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection—CDC Fact Sheet 2014; http://www.cdc.gov/std/HPV/STDFact-HPV.htm.

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV 2014; http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm426485.htm.

- 3.Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(49):1405–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(33):874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(26):661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. AFIX (Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange) 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/AFIX/index.html.

- 7.Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12(6):1566–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilkey MB, Dayton AM, Moss JL, et al. Increasing provision of adolescent vaccines in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2014;134(2):e346–e353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calo WA, Gilkey MB, Leeman J, et al. Coaching primary care clinics for HPV vaccination quality improvement: Comparing in-person and webinar implementation. Transl Behav Med 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scherr CL, Augusto B, Ali K, Malo TL, Vadaparampil ST. Provider-reported acceptance and use of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention messages and materials to support HPV vaccine recommendation for adolescent males. Vaccine 2016;34(35):4229–4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Sutton SK, et al. Missing the target for routine human papillomavirus vaccination: Consistent and strong physician recommendations are lacking for 11–12 year old males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;25(10):1435–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freed GL, Nahra TA, Wheeler JR. Counting physicians: Inconsistencies in a commonly used source for workforce analysis. Acad Med 2006;81(9):847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kletke PR. Physician workforce data: When the best is not good enough. Health Serv Res 2004;39(5):1251–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vadaparampil ST, Kahn JA, Salmon D, et al. Missed clinical opportunities: Provider recommendations for HPV vaccination for 11–12 year old girls are limited. Vaccine 2011;29(47):8634–8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn JA, Zimet GD, Bernstein DI, et al. Pediatricians’ intention to administer human papillomavirus vaccine: The role of practice characteristics, knowledge, and attitudes. J Adolesc Health 2005;37(6):502–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riedesel JM, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, et al. Attitudes about human papillomavirus vaccine among family physicians. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2005;18(6):391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Tissot AM, Bernstein DI, Wetzel C, Zimet GD. Factors influencing pediatricians’ intention to recommend human papillomavirus vaccines. Ambul Pediatr 2007;7(5):367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daley MF, Liddon N, Crane LA, et al. A national survey of pediatrician knowledge and attitudes regarding human papillomavirus vaccination. Pediatrics 2006;118(6):2280–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malo TL, Giuliano AR, Kahn JA, et al. Physicians’ human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations in the context of permissive guidelines for male patients: A national study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23(10):2126–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Kahn JA, et al. Physicians’ human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations, 2009 and 2011. Am J Prev Med 2014;46(1):80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison MA, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE, et al. HPV vaccination of boys in primary care practices. Acad Pediatr 2013;13(5):466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine 2015;33(9):1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss JL, Reiter PL, Dayton A, Brewer NT. Increasing adolescent immunization by webinar: a brief provider intervention at federally qualified health centers. Vaccine . 2012;30(33):4960–4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oster NV, McPhillips-Tangum CA, Averhoff F, Howell K. Barriers to adolescent immunization: A survey of family physicians and pediatricians. J Am Board Fam Med 2005;18(1):13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaffer SJ, Humiston SG, Shone L, Averhoff FM, Szilagyi PG. Adolescent immunization practices: A national survey of us physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155(5):566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szilagyi PG, Rodewald LE, Humiston SG, et al. Immunization practices of pediatricians and family physicians in the United States. Pediatrics 1994;94(4 Pt 1):517–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]