Abstract

Women living with HIV (WLWH) suffer from poor viral suppression and retention postpartum. The effect of perinatal depression on care continuum outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum is unknown. We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using HIV surveillance data of pregnant WLWH enrolled in perinatal case management in Philadelphia and evaluated the association between possible or definite depression with four outcomes: viral suppression at delivery, care engagement within three months postpartum, retention and viral suppression at one-year postpartum. Out of 337 deliveries (2005–2013) from 281 WLWH, 53.1% (n = 179) had no depression; 46.9% had either definite (n = 126) or possible (n = 32) depression during pregnancy. There were no differences by depression status across all four HIV care continuum outcomes in unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The prevalence of possible or definite depression was high among pregnant WLWH. HIV care continuum outcomes did not differ by depression status, likely because of supportive services and intensive case management provided to women with possible or definite depression.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, depression, retention in care, HIV care continuum, maternal health

Introduction

Women living with HIV (WLWH) are disproportionately affected by depression compared to women without HIV (Morrison et al., 2002) and depressive symptoms among WLWH are associated HIV disease progression (Evans, Ten Have, Douglas, Gettes, & Morrison, 2002; Ickovics, Hamburger, Vlahov, Schoenbaum, & Schuman, 2001). Depression can be a strong predictor of non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Ammassari, Antinori, Aloisi, Trotta, & Murri, 2004; Springer, Dushaj, & Azar, 2012) and may contribute to poor maternal outcomes at delivery and postpartum (Alder, Fink, Bitzer, Hösli, & Holzgreve, 2007; Goedhart et al., 2010). Previous studies have shown that WLWH have poor viral suppression at delivery (Momplaisir et al., 2015) and poor retention in HIV care postpartum (Adams, Brady, Michael, Yehia, & Momplaisir, 2015; Momplaisir, Storm, Nkwihoreze, Jayeola, & Jemmott, 2018). The impact of depression on HIV care outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum has not been well described.

Perinatal case management (PCM) is a referral-based voluntary program for pregnant WLWH available in several cities in the United States, including Philadelphia (Anderson, Momplaisir, Corson, & Brady, 2017). The purpose of the program is to support WLWH by addressing structural barriers to care and helping clients optimize engagement in care in order to maintain virologic suppression in the peripartum period. During the intake process with clients, perinatal case managers perform a detailed need assessment and ask women about a current or past diagnosis of depression. This provides the opportunity, along with mandatory reporting of HIV laboratory data to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, to compare care continuum outcomes of WLWH with or without depression during pregnancy. A PCM program has been established in Philadelphia for the past 14 years and has reached over 60% of pregnant WLWH in the catchment area. An evaluation of this program showed higher suppression and postpartum retention among enrolled versus non-enrolled clients (Anderson et al., 2017). However, despite this program, suppression at delivery and engagement in HIV care postpartum remain poor (Momplaisir et al., 2015). This may indicate that other factors, including depression, could be hindering care engagement and adherence to ART. This study evaluates the association between depression during pregnancy and HIV care continuum outcomes of pregnant and postpartum WLWH enrolled in PCM.

Methods

Data source

The data source for this analysis merged PCM records entered in CAREWare (a Ryan White reporting surveillance system) with HIV surveillance data sources, the Enhanced Perinatal System (EPS) and Enhanced HIV/ AIDS Reporting System (eHARS). EPS contains clinical variables of WLWH during pregnancy and up to 30 days after delivery. Postpartum data were obtained by merging EPS and eHARS, a surveillance system of all reported HIV/AIDS cases in Pennsylvania. The combined dataset contained information relevant to depression status and other clinical variables abstracted during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum. This study was approved by the Philadelphia Department of Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) and an exemption was obtained from the Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania IRBs.

Population

The study population consists of WLWH who had a live delivery in Philadelphia (2005–2013) and enrolled in the PCM program during pregnancy. Entry in the cohort began during pregnancy and ended 1 year after delivery. Multiple gestation deliveries (twins and triplets) were included as a single observation and each delivery was treated as an independent event.

Outcome variables

Viral suppression at delivery was defined as having a viral load (VL) ≤200 copies/ml using the VL closest to delivery. This cut-off was used in the early years of our study period and applied to the entire cohort for consistency.

Postpartum engagement in HIV care was defined as having ≥1 CD4 or VL in the first 90 days post-delivery (Adams et al., 2015).

Retention in HIV care at one-year postpartum was defined as having ≥1 CD4 or VL in each 6-month interval of the postpartum period with ≥60 days between tests (U.S. DoHHS, 2016).

Viral suppression at one-year postpartum was defined as having a VL ≤ 200 copies/mL, using the lab closest to the end of the postpartum year.

Exposure variable

A diagnosis of depression during pregnancy was classified as definite, possible or no depression. A definite diagnosis of depression included cases when the diagnosis was made by a healthcare provider, when women reported having a diagnosis of depression, current suicidal ideation or suicidal attempt during pregnancy. Women were classified as having possible depression when they had indicators of depressive symptoms but no formal diagnosis was made. Women with no depression included those with no diagnosis or symptoms of depression and those with a low Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scores. Other mental illness diagnoses were also collected.

Independent variables

Demographic variables included age, race and previous live births. Psychosocial variables included drug use which captured nicotine, alcohol and illicit substance use; intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as experiencing physical, sexual or emotional abuse; history of child sexual abuse, defined as having non-consensual sex as a child; exchange of sex for money or drugs; housing instability, defined as being in a shelter, in the street, sleeping on someone else’s couch, frequently switching houses, or being unable to pay rent; poor support, defined as having limited emotional, financial, or instrumental support during pregnancy and this was measured for partner(s) and family members; and legal issues, which included a history of incarceration or parole violation during pregnancy. We measured the number of PCM encounters which included face-to-face contact, phone calls and home visits.

Data analysis

Univariate analyses were performed to assess the data quality and review frequency distributions for each variable. Bivariate analysis was used to describe the relationship between possible or definite depression and the covariates; possible or definite depression and outcomes variables. Multivariable logistic regression measured the association between possible or definite depression and the four study outcomes adjusting for all demographic, psychosocial and clinical variables described. All covariates were included in each model based on a priori hypotheses.

Results

Demographic and clinical differences among women enrolled versus not enrolled in PCM are described in detail elsewhere (Anderson et al., 2017). A total of 337 deliveries took place among 281 WLWH among whom 53.1% (n = 179) had no depression, 37.4% (n = 126) had definite depression and 9.5% (n = 32) had possible depression, with a total of 158 (46.9%) having possible or definite depression during pregnancy (Table 1). Other history of mental illness included bipolar disorder (15.2%), post-traumatic stress disorder (2.4%) and schizophrenia (1%). About 2.3% (n = 8) of women reported suicidal ideation or attempt during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Demographic, psychosocial and clinical characteristics of pregnant women living with hiv enrolled in PCM, 2005–2013.

| Total cohort | No depression | Possible or definite depression* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=337 | Total n=179 (53.1%) | Total n= 158 (46.9%) | p-Value | |

| Demographic variables, n (%) | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16–24 | 103 (30.6) | 61 (34.1) | 42 (26.6) | 0.17 |

| 25–34 | 175 (51.9) | 92 (51.4) | 83 (52.5) | |

| ≥35 | 59 (17.5) | 26 (14.5) | 33 (20.9) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 22 (6.5) | 15 (8.4) | 7 (4.4) | 0.34 |

| Black | 273 (81.0) | 142 (79.3) | 131 (82.9) | |

| Hisp/Other | 42 (12.5) | 22 (12.3) | 20 (12.7) | |

| Previous live births 0 | 86 (25.5) | 56 (31.3) | 30 (19.0) | <0.05 |

| 1–2 | 155 (46.0) | 85 (47.5) | 70 (44.3) | |

| >2 | 96 (28.5) | 38 (21.2) | 58 (36.7) | |

| Psychosocial variables, n (%) | ||||

| Drug use during pregnancy | ||||

| No | 258 (76.6) | 149 (83.2) | 109 (69.0) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 79 (23.4) | 30 (16.8) | 49 (31.0) | |

| Intimate partner violence | ||||

| No | 256 (76.0) | 152 (84.9) | 104 (65.8) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 81 (24.0) | 27 (15.1) | 54 (34.2) | |

| Child sexual abuse | ||||

| No | 309 (91.7) | 172 (96.1) | 137 (86.7) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 28 (8.3) | 7 (3.9) | 21 (12.3) | |

| Exchange of sex for money or drugs | ||||

| No | 324 (96.1) | 176 (98.3) | 148 (93.7) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 13 (3.9) | 3 (1.7) | 10 (6.3) | |

| Unstable housing | ||||

| No | 152 (45.1) | 85 (47.5) | 67 (42.4) | 0.350 |

| Yes | 185 (54.9) | 94 (52.5) | 91 (57.6) | |

| Poor partner support | ||||

| No | 201 (59.6) | 124 (69.3) | 77 (48.7) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 136 (40.4) | 55 (30.7) | 81 (51.3) | |

| Poor family support | ||||

| No | 236 (70.0) | 141 (78.8) | 95 (60.1) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 101 (30.0) | 38 (21.2) | 63 (39.9) | |

| Incarceration or parole violation | ||||

| No | 276 (81.9) | 155 (86.6) | 121 (76.6) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 61 (18.1) | 24 (13.4) | 37 (23.4) | |

| Number of PCM encounters**, mean (SD) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 50.8 (62.5) | 39.24 (50.79) | 63.64 (71.38) | <0.05 |

| HIV care continuum outcomes | ||||

| Viral suppression at delivery | 219 (65.0) | 85 (63.4) | 134 (66.0) | 0.627 |

| Engagement in HIV care within 3 months postpartum | 141 (41.8) | 56 (41.8) | 85 (41.9) | 0.988 |

| Retention in HIV care at one-year postpartum | 174 (51.6) | 63 (47.0) | 111 (54.7) | 0.168 |

| Viral suppression at one-year postpartum | 145 (43.0) | 50 (37.3) | 95 (46.8) | 0.085 |

Possible or definite depression combined a definite diagnosis of depression (cases when the diagnosis of depression was made by a healthcare provider, when women reported having a diagnosis of depression, current suicidal ideation or suicidal attempt during pregnancy) and possible depression (cases when women had indicators of depressive symptoms, but no formal diagnosis of depression was made).

PCM, perinatal case management.

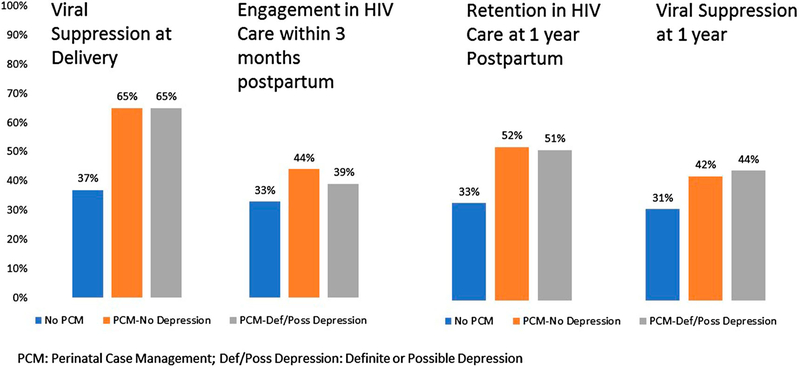

Women experienced many psychosocial stressors and most of these stressors were associated with possible or definite depression (Table 1). About a quarter of women reported using drugs or experiencing IPV and 4% were exchanging sex for money or drugs. More than half of women (55%) experienced unstable housing while pregnant and many had poor partner (40%) or family (30%) support. Despite the high prevalence of psychosocial stressors, the majority of women achieved viral suppression at delivery but postpartum, retention and viral suppression were poor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HIC care continuum outcomes of women in the perinatal period by depression status, 2005–2013.

The number of PCM encounters was substantially higher among women with possible or definite depression compared to women with no depression (63.6 vs. 39.2, p < 0.05). There were no differences by depression status across all four HIV care continuum outcomes in unadjusted (Figure 1) and adjusted analyses (Table 2). A secondary data analysis was performed separating definite and possible depression into their own categories and evaluating their relationship with care continuum outcomes and the findings remained the same.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the association between possible or definite depression and HIV care continuum outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum, 2005–2013.

| Viral suppression at delivery |

Engagement in HIV care at 3 months postpartum |

Retention in HIV care at one-year postpartum |

Viral suppression at 1 year postpartum |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Depression | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Possible or definite depression | 1.0 | [0.6–1.7] | 0.7 | [0.4–1.2] | 0.9 | [0.5–1.4] | 1.0 | [0.6–1.7] |

| Age | ||||||||

| 16–24 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 25–34 | 1.2 | [0.7–2.2] | 0.9 | [0.5–1.7] | 0.9 | [0.5–1.5] | 1.9 | [1.0–3.4] |

| ≥35 | 1.2 | [0.6–2.6] | 1.2 | [0.6–2.6] | 0.9 | [0.4–1.8] | 2.9 | [1.3–6.2] |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Black | 0.5 | [0.1–1.5] | 0.9 | [0.3–2.2] | 1.4 | [0.5–3.7] | 0.6 | [0.2–1.6] |

| Hisp/other | 0.3 | [0.1–1.3] | 0.6 | [0.2–1.8] | 1.0 | [0.3–3.0] | 0.6 | [0.2–1.9] |

| Previous live births | ||||||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 1–2 | 1.0 | [0.6–1.9] | 0.6 | [0.3–1.1] | 1.0 | [0.6–1.8] | 1.0 | [0.6–1.9] |

| >2 | 0.8 | [0.4–1.6] | 1.0 | [0.5–1.9] | 1.3 | [0.6–2.7] | 0.8 | [0.4–1.7] |

| Drug use during pregnancy | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | [0.5–1.9] | 0.6 | [0.3–1.2] | 0.7 | [0.4–1.3] | 1.2 | [0.7–2.2] |

| Intimate partner violence | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | [0.5–1.9] | 1.4 | [0.7–2.5] | 2.0 | [1.1–3.6] | 0.9 | [0.4–1.6] |

| Child sexual abuse | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.7 | [0.6–4.3] | 1.0 | [0.4–2.4] | 1.2 | [0.5–2.8] | 1.3 | [0.5–3.0] |

| Exchange of sex for money or drugs | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.4 | [0.1–1.5] | 0.9 | [0.2–3.2] | 1.5 | [0.4–5.6] | 0.8 | [0.2–2.8] |

| Unstable housing | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | [0.6–1.6] | 1.0 | [0.6–1.6] | 0.9 | [0.6–1.5] | 0.9 | [0.6–1.5] |

| Poor partner support | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.6 | [0.3–1.0] | 0.9 | [0.5–1.5] | 0.6 | [0.3–1.0] | 0.9 | [0.5–1.5] |

| Poor family support | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.1 | [0.6–1.9] | 1.2 | [0.7–2.0] | 1.0 | [0.6–1.6] | 1.0 | [0.6–1.7] |

| Incarceration or parole violation | ||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.1 | [0.6–2.2] | 1.2 | [0.6–2.3] | 1.2 | [0.6–2.3] | 1.0 | [0.5–1.9] |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio. The regression models for each outcome included all listed variables.

Discussion

In this large cohort of WLWH, we found that the majority of women had possible or definite depression during pregnancy and experienced many psychosocial stressors. Despite these challenges, there were no differences found across HIV care continuum outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum. Women with depression benefited from more intensive support from PCM as demonstrated by the higher number of encounters. Engagement in PCM likely helped women overcome barriers that could have impeded attendance to medical visits and adherence to ART.

Our findings are consistent with other published data showing high prevalence of depression for pregnant WLWH. A literature review of studies from high-income countries show that the prevalence of depression among pregnant WLWH varies between 31% and 53% (Kapetanovic, Christensen, Karim, Lin, & Mack, 2009; Kapetanovic, Dass-Brailsford, Nora, & Talisman, 2014; Levine, Aaron, & Criniti, 2008). Having a low CD4 and poor adherence to ART have been associated with perinatal depression (Kapetanovic et al., 2009); however, the direction of the relationship remains unclear. The lack of association between depression and care continuum outcomes in the perinatal period that we observed is likely due to the support provided by PCM or through PCM initiated linkage to mental health programs or other community resources. Interventions aimed at improving retention and viral suppression of pregnant or postpartum WLWH are lacking (Momplaisir et al., 2018); it is therefore important to note that WLWH who receive intensive PCM do not experience worse outcomes than women with no depression.

Limitations for this study include the fact that depression status was only available among women enrolled in PCM; it is possible that a difference in outcomes could have been found if depression status was available for all women (PCM enrollees and non-enrollees). However, referral to PCM is usually made in a higher risk pool of clients and despite experiencing many psychosocial stressors, outcomes were similar by depression status. Another limitation is that we relied on PCM documentation for depression status but PCM notes were generally detailed and inclusive of a diagnosis of depression.

In conclusion, pregnant WLWH with possible or definite depression had similar care continuum outcomes to those without depression. These findings likely reflect the beneficial effects of intensive PCM to offset the negative impact of depression in pregnancy and postpartum.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the perinatal case management program in Philadelphia who care for pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. No official endorsement by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health or National Institutes of Health should be inferred.

Funding

This study was funded by the Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center (PMHARC) pilot and by the Drexel Mary Dewitt Pettit Fellowship fund. This work was supported by Drexel Mary Dewitt Pettit Fellowship fund and University of Pennsylvania Center for AIDS Research (CFAR).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the CFAR symposium, 30 September 2016 and as a poster at 7th International Workshop on HIV and Women, Seattle, Washington, 6 February 2017.

References

- Adams JW, Brady KA, Michael YL, Yehia BR, & Momplaisir FM (2015). Postpartum engagement in HIV care: An important predictor of long-term retention in care and viral suppression. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 61 (12), 1880–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hösli I, & Holzgreve W (2007). Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 20(3), 189–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammassari A, Antinori A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli L, … Starace F (2004). Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosomatics, 45(5), 394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EA, Momplaisir FM, Corson C, & Brady KA (2017). Assessing the impact of perinatal HIV case management on outcomes along the HIV care continuum for pregnant and postpartum women living With HIV, Philadelphia 2005–2013. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Ten Have TR, Douglas SD, Gettes DR, Morrison M, Chiappini MS, … Wang YL (2002). Association of depression with viral load, CD8 T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(10), 1752–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedhart G, Snijders AC, Hesselink AE, van Poppel MN, Bonsel GJ, & Vrijkotte TG (2010). Maternal depressive symptoms in relation to perinatal mortality and morbidity: Results from a large multiethnic cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(8), 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, … for the HIV Epidemiology Research Study Group (2001). Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA, 285(11), 1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Christensen S, Karim R, Lin F, Mack WJ, Operskalski E, … Kramer F (2009). Correlates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(2), 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Dass-Brailsford P, Nora D, & Talisman N (2014). Mental health of HIV-seropositive women during pregnancy and postpartum period: A comprehensive literature review. AIDS and Behavior, 18(6), 1152–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AB, Aaron EZ, & Criniti SM (2008). Screening for depression in pregnant women with HIV infection. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 53(5), 352–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momplaisir FM, Brady KA, Fekete T, Thompson DR, Roux AD, & Yehia BR (2015). Time of HIV diagnosis and engagement in prenatal care impact virologic outcomes of pregnant women with HIV. PloS One, 10(7), e0132262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momplaisir FM, Storm DS, Nkwihoreze H, Jayeola O, & Jemmott JB (2018). Improving postpartum retention in care for women living with HIV in the United States. AIDS, 32(2), 133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have TT, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, … Evans DL (2002). Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(5), 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Dushaj A, & Azar MM (2012). The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/ AIDS: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 16(8), 2119–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. DoHHS. (2016). HIV/AIDS care continuum. Retrieved from https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/policies/carecontinuum/