Introduction

Gliomas represent the most common primary brain tumor in adults. Low-grade gliomas (LGG) are indolent tumors which almost universally progress to high-grade secondary aggressive tumors, such as glioblastoma. The time course of progression can vary greatly from as little as 2 years to greater than a decade depending on the molecular features and the location of the LGG within the brain. The clinical course of LGG is generally less aggressive than primary glioblastoma and its incidence peaks at an earlier age, during the third and fourth decade of life, as opposed to most glioblastoma cases, which peak in the 6th-7th decade.1–3 Our understanding of the relatedness and uniqueness of these two entities has undergone a revolution during the last decade with the advent of widespread cancer genome sequencing. While clinicians at one time relied only upon pathological grade and morphological features to classify tumors and inform treatment, genomic sequencing of gliomas has generated a paradigm shift in our approach to understanding and treating the disease. In 2009, it was discovered that the vast majority of LGG harbored mutations in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and less frequently in the closely related enzyme IDH2.4

The research community is still in the relatively early stages of transforming the basic scientific advances of the last decade into novel therapeutics. In this chapter, we will discuss molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying LGG pathogenesis and progression to high-grade tumors, as well as potential therapeutic approaches that have emerged from laboratory findings.

Molecular Alterations in Adult Low-Grade Gliomas

In 2009, LGG and secondary glioblastoma, which originates from a preexisting LGG, were shown to harbor characteristic, neomorphic, heterozygous mutations in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1).4 This cytosolic, NADP+ dependent enzyme normally forms a homodimer and takes part in the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), which can then be used for multiple cellular functions.5 Additionally, LGGs lacking a mutation in IDH1 may harbor an analogous mutation in IDH2, a mitochondrial enzyme that also produces α-KG, primarily for the TCA cycle.1 LGG and secondary GBM are not the only contexts in which these mutations are found. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), cholangiocarcinoma, and myelodysplastic syndromes have been found to exhibit the same class of mutations.6,7 Interestingly, the genetic syndrome Ollier Disease, which results from somatic mosaicism for mutations in IDH, is associated with an increased rate of gliomas compared to the general population and an earlier age of diagnosis than seen in the broader LGG patient population.8,9

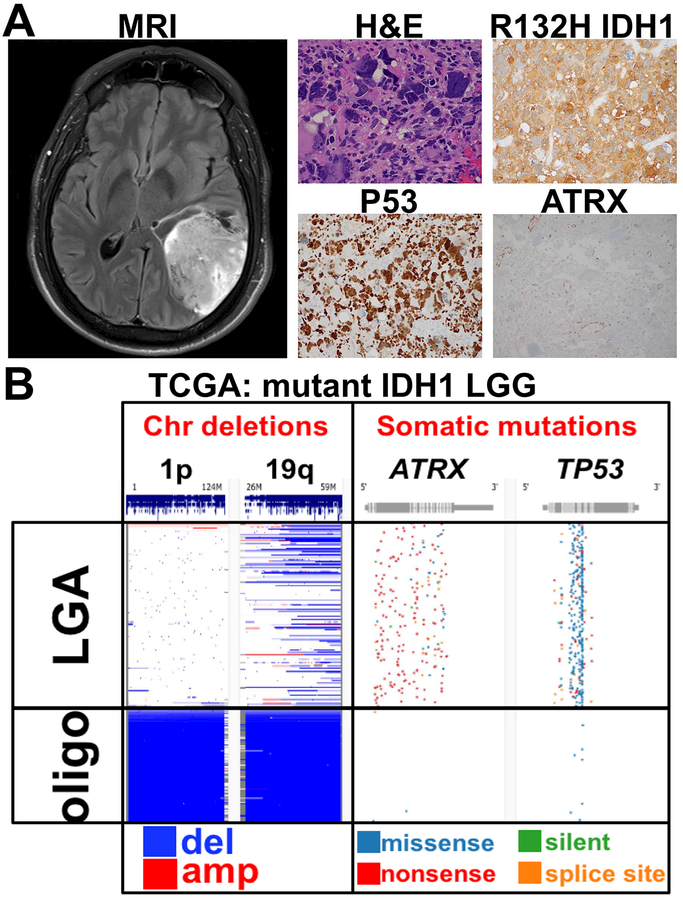

After their initial identification in LGG and secondary glioblastoma, IDH mutations were identified in >80% of tumors histologically classified as LGG.4,10 Further analysis of genomic sequencing revealed the presence of two distinct molecular subclasses within LGG (Fig. 1). The larger of these subclasses is characterized by inactivating mutations in the tumor suppressor TP53 and the chromatin remodeling enzyme ATRX (Fig. 1A,B).2,10 Tumors containing this set of mutations correspond to astrocytoma, as identified by histopathology.11 The smaller subclass is characterized by codeletion of chromosome 1p/19q and promoter mutations in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) (Fig. 1B).11 This latter group of tumors corresponds to oligodendroglioma. IDH mutant and P53/ATRX mutated (astrocytic) LGG has a more aggressive clinical course.11 While IDH mutant 1p/19q co-deleted glioma (oligodendroglioma) shows a less aggressive behavior, significant neurological deterioration and mortality does occur.12,13

Figure 1. Radiographic and histologic features of LGG.

A. The MRI shows a patient with a large, brain-infiltrating IDH mutant astrocytoma. At the histologic level, tumor cells were positive for the R132H IDH1 mutation; P53 nuclear staining, suggesting loss-of-function mutation; and loss of ATRX. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin staining. B. Analysis of genetic profile of IDH1 mutant LGGs in the TCGA. Low-grade astrocytomas (LGA) and oligodendrogliomas (oligo) have mutually exclusive genetic changes. LGAs are characterized by loss-of-function TP53 and ATRX mutations, and do not show the 1p/19q co-deletion seen in oligodendrogliomas.

All of this classification so far neglects the small percentage of histopathologically graded LGGs which do not exhibit a mutation in IDH1/2. It has been suggested that these IDH wild-type gliomas essentially behave like glioblastoma. Indeed, if one looks for markers of IDH wild-type glioblastoma (EGFR amplification, H3F3A K27M, or TERT promoter mutation), they can be found in about half of these patients.14 These patients have an average survival of 1.23 years, comparable to glioblastoma. However, the other half of IDH wildtype LGGs lack these mutations and have a clinical course resembling more closely that of LGG with average survival of greater than 7 years.13,14

The most recent update to the World Health Organization guidelines on the classification of CNS tumors released in 2016 has incorporated the molecular features discussed above into the classification of adult low-grade glioma. Histopathology remains vital in first diagnosing a tumor as a diffuse glioma and then in determining tumor grade. If a tumor is determined to be a diffuse glioma and grade II or III, then molecular diagnostics dictate further classifications. The presence of a mutation in IDH1/2 in combination with loss of ATRX and TP53 results in the diagnosis of a diffuse astrocytoma or anaplastic astrocytoma, grade II and grade III respectively.11 If IDH mutations are found in combination with chromosomal 1p/19q codeletion then the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma or anaplastic oligodendroglioma is made.11 The diagnosis of oligoastrocytoma, previously defined as a tumor with both astrocytic and oligodendroglial histology, still exists in the updated guidelines but is much less common by the new definition. Oligoastrocytomas now must possess distinct tumor cell populations with the molecular features of both astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, but these are exceedingly rare.15 Finally, those tumors which are histologically grade II or III and lack mutations in the previously discussed genes are grouped by histology into either IDH wild-type astrocytoma, or oligodendroglioma not otherwise specified (NOS).11

Molecular Pathogenesis of Low-Grade Astrocytoma

Patient genomic analysis established the mutations discussed previously as being nearly pathognomonic for low-grade astrocytoma (LGA) and oliodendroglioma (LGO), but studying how each individual mutation or combination of mutations contribute to tumorigenesis is important for making this information therapeutically actionable. It was previously recognized that a fraction of GBM and a majority of LGG shared a genome-wide pattern of increased DNA methylation termed glioma-CpG island methylator phenotype (G-CIMP).16 The best studied consequence of DNA methylation is the silencing of gene expression when gene promoter regions are methylated.17 However, the effects do not stop here. High levels of methylation have been linked to heightened mutagenesis in colorectal cancer, another malignancy where many tumors exhibit increased CpG island methylation.18 Beyond modifying gene promoter activity, genomic methylation can affect expression by altering chromatin organization.19–22 While the exact consequences of the G-CIMP phenotype are not clear, analysis of the actions of mutant IDH provided a mechanistic link to its establishment.

Evidence for IDH mutations as a driver of gliomagenesis was supported by their presence in a number of distinct glioma subtypes and other tumors, but the strongest evidence was seen in studies of IDH-mutant glioma recurrences after initial treatment.23 It has been convincingly shown that if an initial tumor contains a mutant IDH then 100% of recurrences will also contain the same exact mutation.23 This strongly supports the hypothesis that mutations in IDH1/2 are the driving event behind the formation of an IDH mutant LGG and remain necessary for tumor progression.

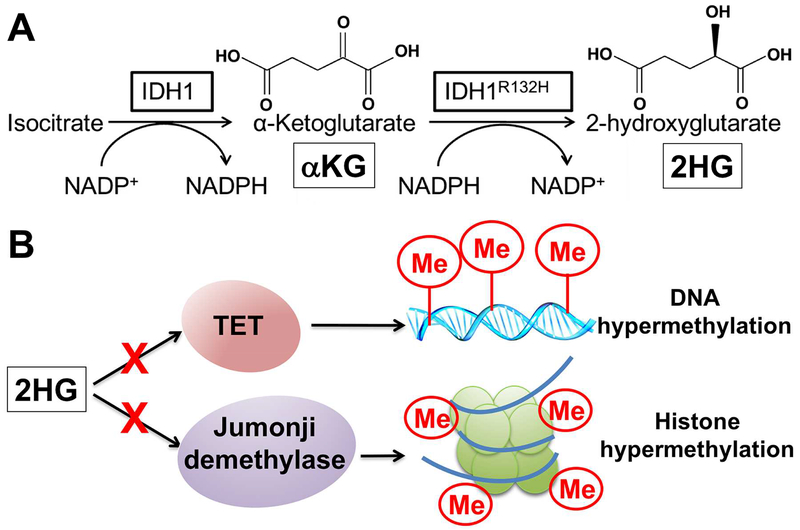

As mentioned above, IDH1 is a cytosolic enzyme which catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate to α-KG, which is then used for multiple metabolic purposes and is required by a class of enzymes called dioxygenases for catalytic activity (Fig. 2A).24 Among these enzymes, some are responsible for removing chromatin methylation, on both DNA and histones.25,26 IDH2 is a homologous enzyme found in the mitochondria and produces α-KG for use in the TCA cycle, a process necessary for aerobic metabolism and ATP production. In contrast, the neomorphic IDH mutations produce the unique metabolic product 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG)27, which inhibits dioxygenase calalytic activity, resulting in DNA hypermethylation among other effects (Fig. 2A,B).25 Studies have confirmed that mutant IDH is sufficient to impart the G-CIMP DNA hypermethylation epigenotype seen in patients.25 Furthermore, mutant IDH increases histone methylation, and in particular repressive methylation modifications associated with transcriptionally silent chromatin.28

Figure 2. Metabolic and epigenetic effects of mutant IDH.

A. IDH’s normal role is the production of α-KG, a metabolic intermediate necessary for catalytic activity of enzymes that include Ten-Eleven Translocases (TET), which initiate DNA demethylation, and Jumonji histone demethylases. B. The oncogenic production of 2HG directly inhibits such enzymes, leading to DNA and histone hypermethylation.

Low-grade astrocytomas, as discussed previously, harbor inactivating mutations of TP53 and ATRX. P53 is a stereotypical tumor suppressor whose inactivation is observed in 50% of all human cancers.29 Its ability to halt cell cycle progression in response to cellular stresses including DNA damage makes it a central player in the preservation of genome integrity and prevention of tumorigenic alterations. Without its activity cells can accumulate extensive mutations and genomic damage while still progressing through the cell cycle, producing progeny containing those errors. Individuals lacking one of the two alleles for TP53 in Li-Fraumeni syndrome are at remarkably increased risk for developing a number of tumors through loss of heterozygosity.30

The function of ATRX is not as clear as P53. ATRX is mutated less often than P53 in cancers, but similar inactivating mutations have been identified in LGG, neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, neuroblastoma, and osteosarcoma among others.31 ATRX is one of many chromatin remodeling enzymes belonging to the SWI/SNF family.32 Chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins in the nucleus, is reversibly modified in a number of ways to alter how accessible areas of the genome are for the purposes of regulating gene expression.32 In particular, ARTX modulates chromatin found near a cell’s telomeres, repeating regions of DNA at the ends of chromosomes.32,33 When ATRX is inactivated, as in LGA, cells begin to undergo a process termed Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT).34,35 Telomeres shorten with each round of cellular division and thus the replicative lifespan of cells is limited by the length of their telomeres. The prototypical method of circumventing this limitation is the expression of telomerase, as in embryonic stem cells, which preserves telomere length, while in certain types of cancer lacking ATRX the ALT mechanism is deployed.36 Inactivation of ATRX has also been observed to contribute to the invasive, migratory phenotype of glioma cells both by itself and in the presence of mutant IDH and loss of P53.22,37 The loss of ATRX in laboratory models is associated with drastic changes in gene expression profiles mirroring those seen human LGA specimens.37

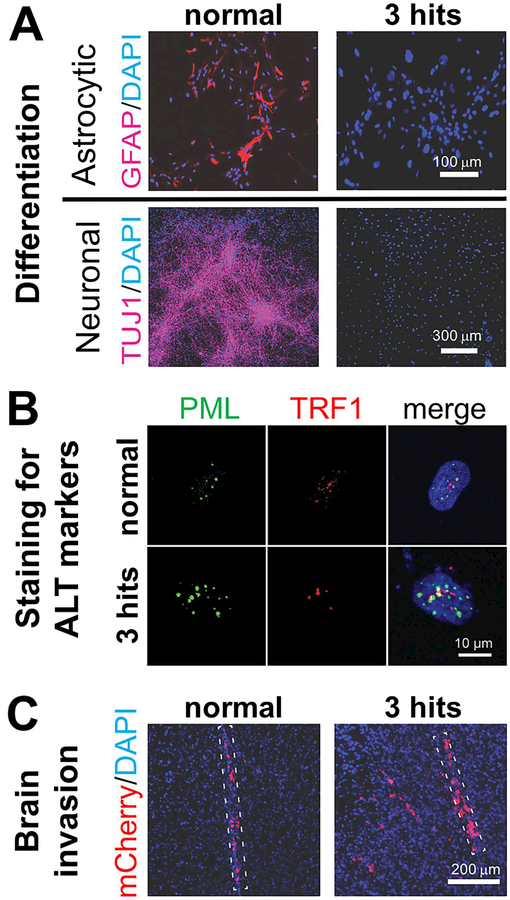

Despite these insights into mutant IDH1 gliomagenesis, the exact mechanism whereby the mutation transforms neural cells into glioma remains unclear.38,39 Our limited understanding of the disease process is in large part related to lack of patient-derived xenograft models that recapitulate the disease, due to the inability of LGGs to grow in culture ex vivo. To overcome this limitation and elucidate cellular and molecular mechanisms of LGG pathogenesis, we recently developed a novel LGG model that is based on a human neural stem cell (hNSC) platform.22 We derived these hNSCs from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and genetically engineered them to express mutant IDH1 (the R132H mutation), as well as short hairpin RNAs that specifically knockdown P53 and ATRX, to mimic the stereotypic genetic background of LGA. While these 3 genetic alterations did not alter cellular proliferation rates, they blocked the ability of hNSCs to differentiate into post-mitotic neuronal and glial lineages (Fig. 3A), similar to what others have described,26,28,40 enabled ALT-dependent telomere elongation (Fig. 3B), and enhanced their ability to infiltrate normal brain tissue (Fig. 3C), a hallmark of LGA. Our findings suggest that the oncogenic mechanism underlying low-grade gliomagenesis is the prevention of generation of post-mitotic neuroglial lineages from brain progenitor cells by the combination of mutant IDH and loss of P53 and ATRX, resulting in the slow growth of undifferentiated, proliferating stem-like tumor cells.22

Figure 3. Effects of mutant IDH on differentiation, telomere elongation and brain invasion.

A. While normal hNSCs can be directed to differentiate to neurons and astrocytes (left), hNSCs with the 3 genetic alterations found in LGA (3 hits) show a differentiation block (right). B. Nuclei of hNSCs with the 3 hits demonstrate foci in which PML and TRF1 co-localize (yellow), indicating ALT. C. Injection of normal or 3-hit hNSCs expressing the fluorescent protein mCherry into the brain of immunosuppressed (NOD.SCID) mice reveals a significant increase in brain invasion by 3-hit cells. The dotted lines outline the injection tracks. In all images, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Adapted from Modrek AS, Golub D, Khan T, et al. Low-grade astrocytoma mutations in IDH1, P53, and ATRX cooperate to block differentiation of human neural stem cells via repression of SOX2. Cell Rep. 2017;21(5):1267–80; with permission.

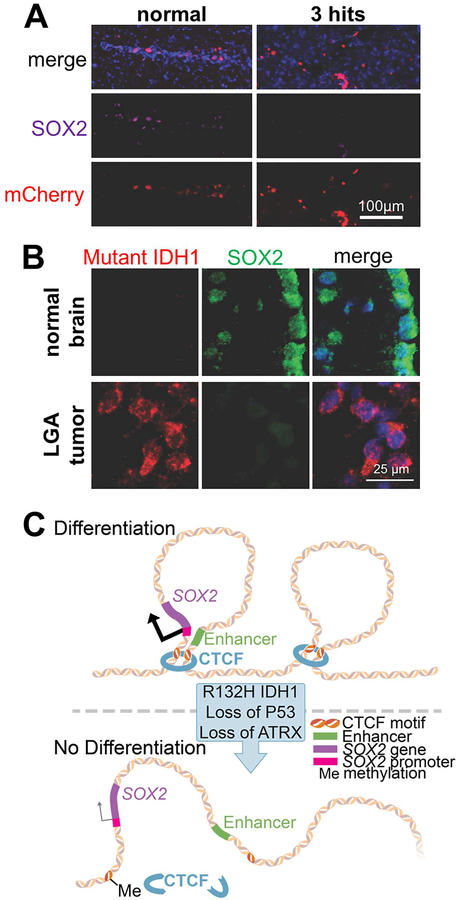

What was even more fascinating though was the molecular mechanism we demonstrated underlies this differentiation block. SOX2 is a transcription factor that is crucial in maintaining the ability of hNSCs to differentiate to neuroglial lineages. We found that SOX2 became transcriptionally downregulated in hNSCs bearing mutant IDH1 and loss of P53/ATRX (Fig. 4A) amid other massive transcriptome changes initiated by the 3 hits. We showed the change in SOX2 expression is necessary and sufficient for the differentiation block, a finding suggesting SOX2 acts as an atypical tumor suppressor during LGA initiation. We also confirmed the change in SOX2 expression between normal human brain tissue and IDH mutant LGA (Fig. 4B). This transcriptional silencing of SOX2 was not due to hypermethylation of its promoter. Instead, our evidence suggests that this effect is mediated by unfolding of the normal chromatin conformation, leading to disassociation of the SOX2 promoter from putative distal enhancer elements located 600–700 kb downstream of the SOX2 locus. We believe the chromatin conformational changes are due to reduced occupancy of CTCF, a protein that helps organize chromatin folding, at its motifs within this genomic neighborhood, partly due to increased DNA methylation (Fig. 4C). This mechanism is similar to one reported in high-grade IDH mutated gliomas.21 More specifically, Flavahan and colleagues found reduced CTCF occupancy leading to abnormal chromatin folding and demonstrated that, as a consequence, a proto-oncogene, PDGFRA, became overexpressed due to ectopic transcriptional activation by an enhancer that it normally does not interact with.21 These findings illustrate the important contribution of altered chromatin conformation to the pathogenesis of LGA.

Figure 4. Mutant IDH alters chromatin conformation in LGA initiation.

A. Confocal microscopic images of hNSCs expressing mCherry injected in the mouse brain. The expression of transcription factor SOX2 is downregulated in 3-hit vs. normal hNSCs. B. Similar to our hNSC model, actual mutant IDH1 LGA tumors show reduced SOX2 expression relative to native neural progenitor cells in the subventricular zone of the normal adult brain. C. Schematic illustrating how methylation of CTCF motifs due to mutant IDH alters chromatin conformation, leading to disassociation of SOX2 promoter from an enhancer and reduced SOX2 transcription. In all images, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Adapted from Modrek AS, Golub D, Khan T, et al. Low-grade astrocytoma mutations in IDH1, P53, and ATRX cooperate to block differentiation of human neural stem cells via repression of SOX2. Cell Rep. 2017;21(5):1267–80; with permission.

Molecular Pathogenesis of Low-Grade Oligodendroglioma

Oligodendrogliomas (LGO) make up a relatively smaller portion of LGG’s and not as well studied as astrocytomas. Mutations in IDH are near universal in LGO and the consequences of this change is much the same as it is in LGA. The pathognomonic molecular changes in LGO are the chromosomal deletion of 1p and 19q and mutations in the promoter of TERT.2 Hemizygous co-deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q results in the loss of a number of genes. TERT promoter mutations, resulting in overexpression of TERT, provide a mechanism by which tumors can maintain telomere length and avoid replicative senescence.41

Beyond the two hallmark changes discussed above, LGO harbors inactivating mutations of the homolog of capicua (CIC) and far-upstream binding protein 1 (FUBP1) in 70% and 30% of cases, respectively.42 These two genes are found on chromosomal segments 1p (FUBP1) and 19q (CIC), so that additional inactivating mutations in the context of 1p/19q co-deletion result complete loss of these proteins. Loss of CIC, a transcriptional repressor, was recently found to promote the proliferation and block the differentiation of neural progenitors43, thus providing a mechanism for oligodendroglioma initiation and growth. FUBP1 mutations are less well characterized but seem to result in transcriptional activation of C-MYC, a transcription factor activated by growth factor signaling, and upregulation of ribosome biogenesis.12,44 Additionally, in normal physiology FUBP1 promotes neural differentiation of progenitor cells.45

Progression to High-Grade Glioma

Mutant IDH LGA and LGO both inevitably progress to high-grade gliomas. A recent study was able to catalog genetic changes underlying this progression by performing whole exome sequencing on LGGs resected upon initial presentation and after their transformation to high-grade tumors23. The most common deletion associated with progression was that of tumor suppressor CDKN2A, while the most common amplification was that of MYC.23 Additionally, the majority of tumors overexpressed EZH2 upon progression.23 EZH2 is the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) and catalyzes the tri-methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3.46 This histone modification is associated with transcriptional repression.47 This finding again suggests a crucial role for regulation of the epigenome in the pathogenesis of IDH mutant glioma.

It has been demonstrated that treatment of IDH mutant LGG with the alkylating agent temozolamide generates a hypermutant genotype in 60% of cases.48 This increased mutational burden is associated with exacerbated malignancy. In contrast, only ~20% of IDH wild-type gliomas respond to chemotherapy with this hypermutation phenomenon.49 Common genetic alterations in the acquisition of the hypermutant genotype include loss of CDKN2A and mutations to other components of the RB tumor suppressor pathway, as well as a number of the components of the MAPK signaling pathway.48

Therapeutic Implications

As with other tumors of the central nervous system, treatment of LGG continues to rely on maximal tumor resection, radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy. Our modern understanding of the unique pathogenic causes of LGG has however spawned a number of experimental approaches to treatment which show promise.

Inhibition of Mutant IDH1/2

A number of inhibitors of mutant IDH have been produced and their use in treating several cancers is now under investigation. These drugs have been validated to specifically inhibit 2HG but not α-KG production. Early clinical data in IDH mutant AML have shown promise. The FDA approved the first compound in late 2017 for this indication.50 Trials in glioma are ongoing due to the longer timeline of the disease. Early preclinical evidence showed promise that inhibitors could slow tumor progression.51 However, later studies have indicated that inhibitors have no inhibitory effect on tumor growth in xenoplant models of glioma despite effective inhibition of 2HG production.52 Current evidence shows that the effects of mutant IDH are long-lasting and remain even following full inhibition of 2HG production. A number of genes, whose expression is changed by 2HG, remain aberrantly expressed following prolonged inhibition of mutant IDH.53

Synthetic Lethality in LGG

A growing area of interest in oncology is finding ways in which oncogenic mutations cause cells to become overly reliant on pathways which healthy cells use but can survive without. If such a pathway is found, targeted interference in its function can eliminate cancerous cells while sparing their healthy counterparts. Using tractable laboratory models of LGG, several such vulnerabilities have been identified.

One of the most potentially disastrous types of DNA damage that cells can incur are DNA breaks. When these breaks occur in healthy cells in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, the preferred mechanism of repair is to use the homologous sister chromatid as a template.54 This high-fidelity mechanism of DNA repair is termed homologous recombination repair (HRR) and preserves genomic integrity. A different and somewhat less effective mechanism, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), is theoretically available for repair throughout the cell cycle but acts primarily in G1 as a result of its suppression in S/G2 by proteins like CYREN.55 Finally, the most error-prone DNA repair mechanism, alternative end-joining (Alt-EJ) is dependent on poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and serves as backup when HRR and NHEJ are not available.56 Lack of repair of DNA breaks by any mechanism results in cell death.

In 2016, Sulkowski and colleagues showed that IDH mutant LGG harbors a defect in HRR and is inherently susceptible to PARP inhibitors because it relies on Alt-EJ for DNA repair.57 This mechanism was previously identified and understood in BRCA1/2-deficient breast cancer- and led to the development of PARP inhibitors.58 Clinical trials have already begun to assess the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in mutant IDH glioma.

Another effect of mutant IDH is to reduce cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) levels by transcriptionally downregulating the NAD+ salvage pathway enzyme nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase (NARPT1).52 Preclinical animal model testing has found strong sensitivity of mutant IDH glioma to NAD+ depletion via inhibition of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the sole enzyme that can support NAD+ biosynthesis in the absence of NARPT1.52 This finding uncovered a metabolic vulnerability of IDH mutant glioma that can be therapeutically exploited.

Cells express proteins which inhibit or activate apoptosis in a context-dependent manner. It was recently demonstrated that mutant IDH can change the balance of these factors.59 The presence of mutant IDH or exogenous 2HG activates the energy-sensing protein AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which has the downstream effect of inhibiting production of MCL1,59 a member of the Bcl-2/Bcl-xL anti-apoptotic family of proteins.60 Because of the low levels of MCL1, treatment of mutant IDH glioma with the compound ABT263, which is an inhibitor of Bcl-xL and Bcl-2, depletes IDH mutant tumor cells of anti-apoptotic activity and confers synthetic lethality with the IDH mutation both in vitro and in vivo.59 This fascinating finding also exposed another selective vulnerability of IDH mutant gliomas not seen in their wild-type counterparts.

Conclusion

In the last decade, much has been learned about LGG molecular pathogenesis. Currently, there are significant efforts to translate this knowledge into clinical trials. The IDH mutation, a hallmark of LGG, is important to understand further in order to be therapeutically targeted. Recent studies are revealing unique vulnerabilities in IDH mutant gioma, which may soon bring forth clinically impactful treatments.

KEY POINTS.

Recent advances in genome sequencing have identified genetic alterations that define low-grade glioma

The IDH mutation initiates metabolic, epigenetic and cellular changes that transform neural progenitors to glioma cells

Laboratory findings are giving rise to novel therapeutic approaches in low-grade glioma

SYNOPSIS.

Advances in genome sequencing have elucidated the genetics of low-grade glioma. Available evidence indicates a neomorphic mutation in IDH initiates gliomagenesis. Mutant IDH produces the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits enzymes that demethylate genomic DNA and histones. Recent findings by us and others suggest the ensuing hypermethylation alters chromatin conformation and the transcription factor landscape in brain progenitor cells, leading to a block in differentiation and tumor initiation. Work in preclinical models has identified selective metabolic and molecular vulnerabilities of low-grade glioma. These new concepts will trigger a wave of innovative clinical trials in the near future.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have nothing to dislose.

References

- 1.Grier JT, Batchelor T. Low-grade gliomas in adults. Oncologist. 2006;11(6):681–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, et al. Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceccarelli M, Barthel FP, Malta TM, et al. Molecular Profiling Reveals Biologically Discrete Subsets and Pathways of Progression in Diffuse Glioma. Cell. 2016;164(3):550–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinekar R, Verma C, Ghosh I. Functional relevance of dynamic properties of Dimeric NADP-dependent Isocitrate Dehydrogenases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13 Suppl 17:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farshidfar F, Zheng S, Gingras MC, et al. Integrative Genomic Analysis of Cholangiocarcinoma Identifies Distinct IDH-Mutant Molecular Profiles. Cell Rep. 2017;19(13):2878–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yen KE, Bittinger MA, Su SM, Fantin VR. Cancer-associated IDH mutations: biomarker and therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene. 2010;29(49):6409–6417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnet C, Thomas L, Psimaras D, et al. Characteristics of gliomas in patients with somatic IDH mosaicism. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amary MF, Damato S, Halai D, et al. Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome are caused by somatic mosaic mutations of IDH1 and IDH2. Nat Genet. 2011;43(12):1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, Korshunov A, Hartmann C, von Deimling A. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(6):597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wesseling P, van den Bent M, Perry A. Oligodendroglioma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(6):809–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bromberg JE, van den Bent MJ. Oligodendrogliomas: molecular biology and treatment. Oncologist. 2009;14(2):155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aibaidula A, Chan AK, Shi Z, et al. Adult IDH wild-type lower-grade gliomas should be further stratified. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(10):1327–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huse JT, Diamond EL, Wang L, Rosenblum MK. Mixed glioma with molecular features of composite oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma: a true “oligoastrocytoma”? Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(1):151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, et al. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(5):510–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGhee JD, Ginder GD. Specific DNA methylation sites in the vicinity of the chicken beta-globin genes. Nature. 1979;280(5721):419–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38(7):787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert N, Thomson I, Boyle S, Allan J, Ramsahoye B, Bickmore WA. DNA methylation affects nuclear organization, histone modifications, and linker histone binding but not chromatin compaction. J Cell Biol. 2007;177(3):401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keshet I, Lieman-Hurwitz J, Cedar H. DNA methylation affects the formation of active chromatin. Cell. 1986;44(4):535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flavahan WA, Drier Y, Liau BB, et al. Insulator dysfunction and oncogene activation in IDH mutant gliomas. Nature. 2016;529(7584):110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modrek AS, Golub D, Khan T, et al. Low-Grade Astrocytoma Mutations in IDH1, P53, and ATRX Cooperate to Block Differentiation of Human Neural Stem Cells via Repression of SOX2. Cell Rep. 2017;21(5):1267–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai H, Harmanci AS, Erson-Omay EZ, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of IDH1-mutant glioma malignant progression. Nat Genet. 2016;48(1):59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature. 2012;483(7390):479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):553–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462(7274):739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;483(7390):474–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408(6810):307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBride KA, Ballinger ML, Killick E, et al. Li-Fraumeni syndrome: cancer risk assessment and clinical management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(5):260–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fishbein L, Khare S, Wubbenhorst B, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic ATRX mutations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clynes D, Higgs DR, Gibbons RJ. The chromatin remodeller ATRX: a repeat offender in human disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(9):461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong LH, McGhie JD, Sim M, et al. ATRX interacts with H3.3 in maintaining telomere structural integrity in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2010;20(3):351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Napier CE, Huschtscha LI, Harvey A, et al. ATRX represses alternative lengthening of telomeres. Oncotarget. 2015;6(18):16543–16558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee J, Johannessen TA, Ohba S, et al. Mutant IDH1 cooperates with ATRX loss to drive the alternative lengthening of telomere (ALT) phenotype in glioma. Cancer Res. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dilley RL, Greenberg RA. ALTernative Telomere Maintenance and Cancer. Trends Cancer. 2015;1(2):145–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danussi C, Bose P, Parthasarathy PT, et al. Atrx inactivation drives disease-defining phenotypes in glioma cells of origin through global epigenomic remodeling. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardella C, Al-Dalahmah O, Krell D, et al. Expression of Idh1(R132H) in the Murine Subventricular Zone Stem Cell Niche Recapitulates Features of Early Gliomagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(4):578–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirozzi CJ, Carpenter AB, Waitkus MS, et al. Mutant IDH1 Disrupts the Mouse Subventricular Zone and Alters Brain Tumor Progression. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15(5):507–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosiak K, Smolarz M, Stec WJ, et al. IDH1R132H in Neural Stem Cells: Differentiation Impaired by Increased Apoptosis. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh KM, Wiencke JK, Lachance DH, et al. Telomere maintenance and the etiology of adult glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(11):1445–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Jiao Y, et al. Mutations in CIC and FUBP1 contribute to human oligodendroglioma. Science. 2011;333(6048):1453–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang R, Chen LH, Hansen LJ, et al. Cic Loss Promotes Gliomagenesis via Aberrant Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Cancer Res. 2017;77(22):6097–6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He L, Liu J, Collins I, et al. Loss of FBP function arrests cellular proliferation and extinguishes c-myc expression. EMBO J. 2000;19(5):1034–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hwang I, Cao D, Na Y, et al. Far Upstream Element-Binding Protein 1 Regulates LSD1 Alternative Splicing to Promote Terminal Differentiation of Neural Progenitors. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10(4):1208–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;469(7330):343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298(5595):1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson BE, Mazor T, Hong C, et al. Mutational analysis reveals the origin and therapy-driven evolution of recurrent glioma. Science. 2014;343(6167):189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Cazzato E, Ladewig E, et al. Clonal evolution of glioblastoma under therapy. Nat Genet. 2016;48(7):768–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nassereddine S, Lap CJ, Haroun F, Tabbara I. The role of mutant IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(12):1983–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, et al. An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science. 2013;340(6132):626–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tateishi K, Wakimoto H, Iafrate AJ, et al. Extreme Vulnerability of IDH1 Mutant Cancers to NAD+ Depletion. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(6):773–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turcan S, Makarov V, Taranda J, et al. Mutant-IDH1-dependent chromatin state reprogramming, reversibility, and persistence. Nat Genet. 2018;50(1):62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li X, Heyer WD. Homologous recombination in DNA repair and DNA damage tolerance. Cell Res. 2008;18(1):99–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arnoult N, Correia A, Ma J, et al. Regulation of DNA repair pathway choice in S and G2 phases by the NHEJ inhibitor CYREN. Nature. 2017;549(7673):548–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang HHY, Pannunzio NR, Adachi N, Lieber MR. Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(8):495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sulkowski PL, Corso CD, Robinson ND, et al. 2-Hydroxyglutarate produced by neomorphic IDH mutations suppresses homologous recombination and induces PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(375). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karpel-Massler G, Ishida CT, Bianchetti E, et al. Induction of synthetic lethality in IDH1-mutated gliomas through inhibition of Bcl-xL. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delbridge AR, Grabow S, Strasser A, Vaux DL. Thirty years of BCL-2: translating cell death discoveries into novel cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(2):99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]