Abstract

In this study, different dosages of calcium polysulphide (CaSx) were used as an amendment to investigate effects on the immobilizing of Cd in a wetland soil by pot experiment. In addition to chemical analysis (pH and bioavailable Cd concentration), changes in soil enzyme activities, microbial carbon utilization capacity, metabolic and community diversity were examined to assess dynamic impacts on soil environmental quality and toxicity of Cd resulting from ameliorant dosing. Soil pH increased immediately upon CaSx amendment compared to the unamended control (CK), and then declined slowly to a level lower than CK. Diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) extractable Cd concentration was determined to characterize the bioavailability of Cd in the soil. The CaSx dose-dependent effect observed that with increasing CaSx dosage, the immobilizing efficiency decreased. Soil urease and catalase activity assays and Biolog EcoPlate assay indicated that early stage addition of CaSx significantly inhibited soil microbial activities. However, mid and late stage time periods showed the inhibition effects were alleviated, and the microbial activities could be recovered in 1% and 2% CaSx treatments. Moreover, with increasing incubation time, microbial community diversity and richness were significantly recovered in 1% and 2% CaSx treatments compared to the CK. No considerable changes were observed in the 5% CaSx treatment. Conclusively, the 1% CaSx amendment was an efficient and safe dosage for the stabilization of Cd contaminated wetland soil. This study contributes to the development of in situ remediation ameliorants and technologies for heavy metal polluted wetland soils.

Keywords: Cadmium, Calcium polysulfide, Bioavailability, Stabilization, Soil enzyme, Microbial diversity.

1. Introduction

Coastal wetland is a transitional zone between the terrestrial and the marine ecosystem. It is strongly affected by global climate change and intensive anthropogenic activity. It provides essential ecosystem services to people and the environment, including providing production and living materials (such as food, raw materials and water resources), protecting biodiversity, degrading pollution and purifying the environment, regulating runoff floods and regional climate control, and serves as tourist and sightseeing destinations (Costa-Böddeker et al., 2017). In recent years, with the rapid development of industrialization, agricultural intensification and urbanization in the coastal zones, a large quantity of industrial wastes, agricultural fertilizers and pesticides, mining wastewaters, and municipal sewage have been emitted to the coastal wetland soils (Xu et al., 2017; Abad-Valle et al., 2016). Contaminants, such as heavy metals, could transfer from these potential waste streams into the coastal wetland soils causing pollution, and resulting human health and ecological risks to the coastal wetland soil ecosystem (Reddy et al., 2009; Bao et al., 2017). According to some investigations reviewed by Pan and Wang (2012), the average Cd concentration in estuarine and coastal environments in China varies from 0 to 9.7 mg kg−1. However, in some particular sites adjacent to mining and smelling districts in the coastal zone of China, Cd concentrations can be as high as 200–400 mg kg−1 (Fan et al., 2006; Zhong et al., 2017). Therefore, it is of great urgency to develop green and sustainable remediation technologies for cost-effective remediation of heavy metal polluted coastal wetland soils.

Unlike most organic contaminants, heavy metals in the soil cannot be totally degraded, but can be controlled and remediated through the following two in-situ strategies. One is to extract heavy metals from the polluted soil with technologies such as chemical/biological leaching and phytoextraction. The other is to decrease the mobility and bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil by adding natural or chemical/biological synthesized amendments, also known as solidification/stabilization (Lee et al., 2009; Koptsik, 2014). Due to its economic efficiency and environmental compatibility, stabilization has been widely and successfully applied in the remediation of the heavy metal-polluted soils in farmland, industrial sites, mining areas, as well as coastal wetlands. Common stabilization agents used in the heavy metal polluted soils include phosphates (such as apatite, hydroxyapatite, bone meal, etc.), organic substances (such as humic acid, chitosan, straw, organic fertilizer, biochar, etc.) and other minerals (such as zeolite, lime, red mud, bentonite, sepiolite, etc.) (Lee et al., 2009; Janoš et al., 2013; Koptsik, 2014; Maletić et al., 2015; Abad-Valle et al., 2016; Guemiza et al., 2017). Their stabilization mechanisms vary with respect to different types of stabilization agents, soil physicochemical properties, as well as soil microbial activities.

Calcium polysulphide (CaSx), also called lime sulphur, is a common soil bactericide and insecticide which has been widely applied in prevention and eradication of plant diseases and insect pests in agricultural production approved by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Due to its strong reducibility and solidification of heavy metals, CaSx has been considered as an ideal stabilization agent, and has been applied in the control and remediation of chromium (Cr) contaminated soil and waste water (Yahikozawa et al., 1978; Chrysochoou et al., 2010; Chrysochoou and Ting, 2011; Kameswari et al., 2015). CaSx rapidly transformed hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) from a highly mobile and toxic species to the immobile and lower toxicological Cr(III) form, which caused the geochemical fixation of Cr (Fruchter, 2002). Chryosochoou et al. (2010) added CaSx to Cr(VI)-contaminated soils and found the solubility of transformed Cr(III) was continually decreased over one year of incubation, indicating high efficiency and long-term stabilization of Cr. Maletić et al. (2015) compared the stabilization effects of four ameliorants, including bone meal, activated carbon, bentonite and CaSx to the stabilization of Pb, Cu and Ni-contaminated soils. They found CaSx had better stabilization effects on the heavy metals than other ameliorants, and the stabilization effects increased with increasing dosages of CaSx. However, to our knowledge, researches regarding on the remediation of Cd-contaminated soil by CaSx are very limited. Furthermore, the environmental impacts of CaSx application to the coastal wetland soil ecosystem remains unclear.

The aim of the present study was therefore to investigate the stabilization effects of CaSx on the remediation of Cd-contaminated wetland soil, and to clarify the dosage-dependent effects of CaSx application on soil enzyme activities and soil microbial metabolic and community diversity. The results of this study will be helpful to the development of an efficient, safe and long-acting stabilization soil amendment for the in-situ remediation of Cd-contaminated wetland soil.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Physicochemical properties of the tested soil

The tested soil was collected from the surface layer of the coastal wetland in Shandong Province, China. The basic physicochemical properties were as follow: pH 7.85, soil organic matter 8.04 g kg−1, EC 0.13 ms cm−1, total N 0.56 g kg−1, total P 1.09 g kg−1, total K 15.36 g kg−1, CEC 5.40 cmol kg−1, Na 13.88 g kg−1, Ca 14.81 g kg−1, Cd 0.22 mg kg−1, sandy loam. It belongs to Fluvisols according to the FAO soil classification system.

2.2. Preparation of the soil stabilization amendment CaSx

The tested soil stabilization amendment CaSx was prepared according to the method modified from Levchenko et al. (2015). Briefly, CaO, S and distilled water were mixed (1:2:15) and heated at 100°C for 2 h to produce the CaSx by the following reaction:

| (1) |

The reaction yields CaS4 and CaS5 (64–67%) and by-products of CaS2O3 (23–28%) and CaCO3 (0.3–1.1%), with 5–11% unreacted sulfur remaining. The main active ingredient of CaSx are CaSx (x=5–8) as well as other components such as HS-, CaSO4, CaO, S and Ca(OH)2. The mixture was then filtered after it was cooled to room temperature. The filtered CaSx was a dark orange solution, while the pale-yellow precipitate was composed of CaS2O3, CaCO3, and unreacted sulfur. Since CaSx can be easily oxidized when exposed to air, the filtered CaSx was sealed by liquid paraffin and stored in the bottle before using.

2.3. Soil stabilization remediation experiment design

The tested soil was disaggregated and sieved to a final size of < 2 mm after air dried. 5 kg of sieved soil was artificially spiked with 500 mL of Cd(NO3)2 stock solution (Cd concentration 2.1 g L−1), and aged for 2 weeks to attain equilibrium. The final concentration of total Cd in the soil was 95 mg kg−1. Soil moisture content was adjusted to 30% of the water holding capacity (WHC) before the pot experiment.

Soil stabilization remediation was conducted by pot experiment. Four treatments were designed with different CaSx amendment dosage: (i) Cd spiked soil without CaSx amendment (CK), (ii) Cd spiked soil with 1% (v:m) CaSx amendment (C1), (iii) Cd spiked soil with 2% (v:m) CaSx amendment (C2) and (iv) Cd spiked soil with 5% (v:m) CaSx amendment (C5). Each pot was filled with 300 g (dry weight) soil with the WHC maintained at 30%. All the treatments were conducted in the green house at room temperature, with 3 replicates. Soil samples were collected from all the treatments at 0 d (30 min), 3 d, 15 d, 30 d, 40 d and 55 d, respectively, for further analysis.

2.4. Soil pH and total Cd analysis

Soil pH was measured by pH meter (F2, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) at a 1:2.5 (w:v) ratio of soil and deionized water. The total Cd content in the soil was analyzed using a HNO3-HF-HClO4 digestion followed by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (AA7000, Shimadzu, Japan).

2.5. Soil bioavailable Cd analysis

Diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) is a one-step extracting agent that has been widely used to predict the bioavailability of heavy metals in soil (Udovic and Lestan, 2012; Luce et al., 2017). In this research, DTPA extractable Cd was adopted to characterize the bioavailability of Cd in the soil according to Kopittke et al. (2017). 10 mL of DTPA extracting agent was added into a 50-mL tube containing 5 g of air-dried soil passed through a 1 mm mesh. The mixture was oscillated at 180 r min−1, 25℃ for 2 h, then filtered and diluted before the analysis of bioavailable Cd detected by atomic absorption spectrometry.

2.6. Soil enzymatic activities assay

Soil urease activity was determined using the sodium hypochlorite-sodium phenate colorimetry assay with urea as the substrate, and was expressed as μg NH4+-N g−1 soil 24 h−1 (Bhaduri et al., 2016). Soil catalase activity was determined using the permanganimetric assay with hydrogen peroxide as the substrate, and was expressed as μmol H2O2·g−1 soil·24 h−1 (Jorge-Mardomingo et al., 2013). Blank matrix control was set for each treatment, while blank sample and matrix control were set during the whole experiment.

2.7. Soil microbial carbon utilization characteristics

Soil microbial carbon source utilization characteristics was analyzed using the Biolog EcoPlate assay (Jiang et al. 2017). The Biolog EcoPlate (Biolog Inc., Hayward, USA) contains 31 of the most useful carbon sources for soil community analysis, which belong to 6 categories including carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, polymers, amino acids, phenolic acids and amines. Soil suspensions (150 μL) were inoculated directly into Biolog EcoPlates and the microplates were incubated and analyzed at defined time intervals. Formation of purple color occurs when the microbes can utilize the carbon source and begin to respire. The community-level physiological profile is assessed by the rate of average well color development (AWCD) measured at OD590 on a microplate reader. The AWCD value is calculated according to formula (2) (Braun et al., 2010).

| (2) |

Here, Ci is the OD590 value of the ith non-control well, R is the OD590 value of the control well, and 31 is the number of carbon sources in the Biolog EcoPlate.

2.8. Soil microbial community diversity

Soil microbial community diversity indexes, i.e. Shannon index (H), Simpson index (D) and McIntosh index (U) are calculated using the following formulas according to Liu et al. (2017):

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Here, pi is the ratio between the relative OD590 value (Ci-R) of the ith well and the sum of the entire plate, ni is the relative OD590 value (Ci-R) of the ith well, N is the sum of OD590 value. Soil microbial community Richness index (R) refers to the total number of carbon sources used by soil microbes. It is expressed as the number of wells whose OD590 value (Ci-R) > 0.15 in each plate (Mahabadi et.al. 2007).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Mean values and standard deviation (SD) of the data were calculated by Excel 2016. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 21.0 software. The significant difference analysis was evaluated by the Duncan’s test of difference analysis variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Dynamics of soil pH and DTPA extractable Cd concentration

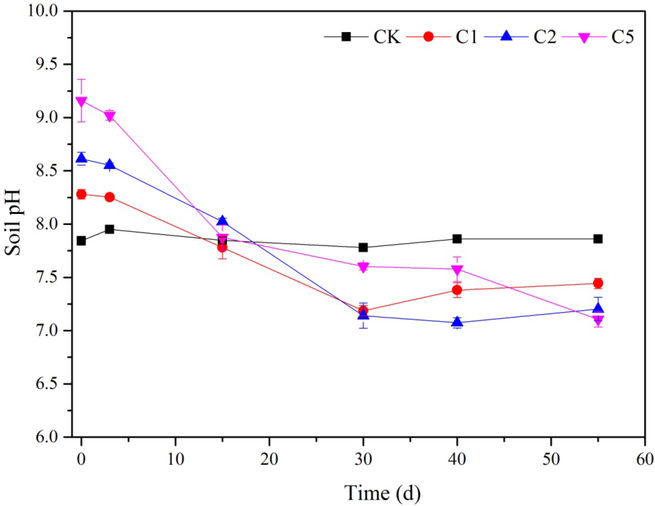

Soil pH variation dynamics in Cd polluted wetland soil amended by different dosages of CaSx is presented in Fig. 1. Within the entire remediation duration, soil pH in the control treatment (CK) without CaSx application maintained in an alkalescent range (pH 7.86±0.1), while soil pH in all the CaSx amendment groups showed a significant increase relative to the control immediately after addition of CaSx to the soil (30 min, 0 d). The soil pH in 1%, 2% and 5% CaSx treatments were respectively 8.28, 8.61 and 9.16. The pH enhancement was directly correlated with the increasing of CaSx dosage. However, as reaction time progressed, soil pH in all CaSx treatments showed a rapid decrease. At the end of the experiment (Day 55), soil pH of all the treatments with CaSx amendment were significantly lower than CK, and the extent of pH decrease was positively correlated with dosage level of CaSx (p<0.05).

Fig. 1.

Dynamic changes of soil pH under different doses of CaSx amendment

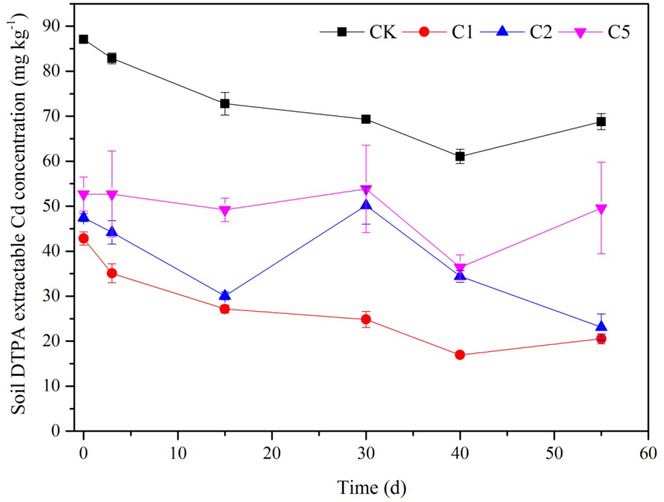

Dynamics of soil DTPA extractable Cd concentration in different treatments is shown in Fig. 2. DTPA extractable Cd concentrations in 1%, 2% and 5% CaSx treatments were 42.84, 47.47 and 52.69 mg kg−1, respectively, which were significantly decreased compared with CK (87.10 mg kg−1) immediately after the addition of CaSx (30 min, 0 d). Upon aging, DTPA extractable Cd concentration in C1 group kept decreasing within the entire experiment period and was markedly lower than that in C2 and C5. At the end of the experiment (Day 55), DTPA extractable Cd concentrations in CK, C1, C2 and C5 were 61.06, 20.53, 23.10 and 49.59 mg kg−1, respectively. For all the treatments with CaSx amendment, DTPA extractable Cd was significantly lower than that of the CK. The stabilization effect of CaSx on soil Cd was not positively correlated with the dosage of CaSx. On the contrary, the most efficient treatment for Cd immobilization was C1 with the lowest CaSx amendment.

Fig. 2.

Dynamic changes of soil DTPA extractable Cd concentration under different doses of CaSx amendment

3.2. Dynamics of soil urease and catalase activities

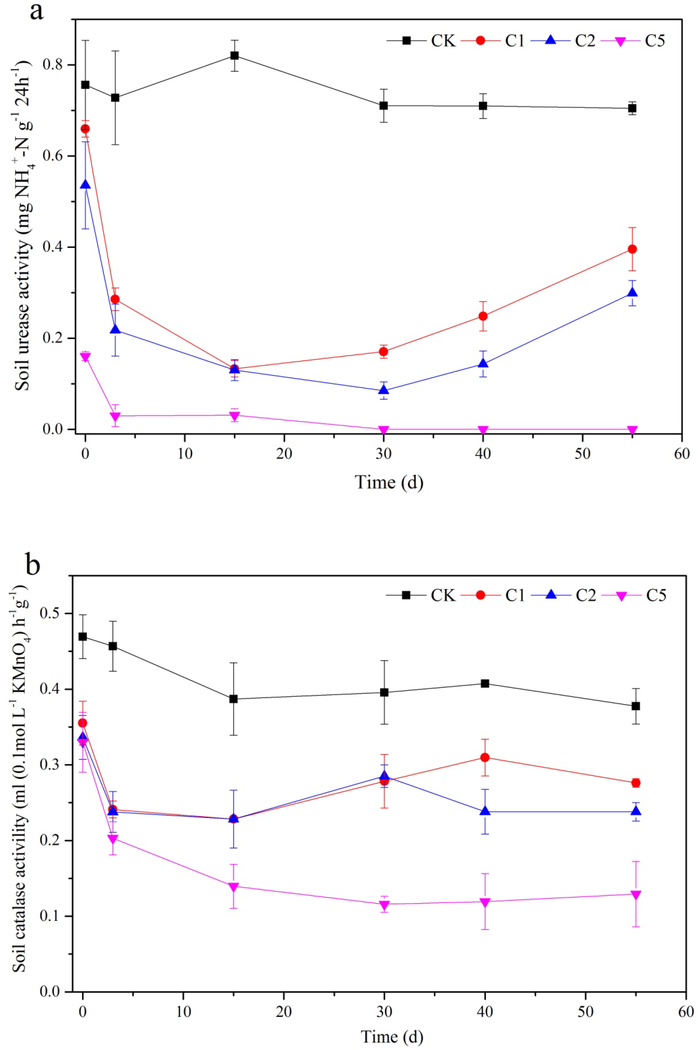

Urease and catalase are two types of typical soil enzymes that are widely used for the evaluation of soil environmental quality and microbial activities. Dynamics of soil urease and catalase activities in the Cd polluted soil amended by CaSx are presented in Fig. 3. Soil urease activity decreased significantly (p<0.05) in all treatments immediately after CaSx was added to the soil. At Day 0 (30 min), soil urease activities in 1%, 2% and 5% CaSx treatments were reduced by 12.74%, 18.79% and 70.03% compared to the CK. As reaction time increased, urease activity in C1 kept declining to 0.13 mg NH4+ N g−1 24 h−1 during the first 15 d, then it slowly recovered, increasing to 0.40 mg NH4+ N g−1 24 h−1 at the end of experiment (Day 55). Urease activity in C2 was similar to C1, except the recovery inflexion starts later (Day 30) than C1, and the soil urease activity in C2 (0.30 mg NH4+ N g−1 24 h−1) was significantly lower than C1 at Day 55. However, urease activity in C5 was totally different from that of C1 and C2. Through Day 3, soil urease activity in C5 decreased rapidly to 0.03 mg NH4+ N g−1 24 h−1, and maintained at a very low level around the detection limit for the duration of the study. There was no significant change for soil urease activity in the CK group during the whole experiment.

Fig. 3.

Dynamic changes of soil enzyme activities under different doses of CaSx amendment (a: urease activity, b: catalase activity)

The general dynamics of soil catalase activities were similar to the urease activities (Fig. 3b). Compared to CK, soil catalase activities decreased significantly (p<0.05) in all treatments immediately after CaSx was added to the soil. For 1% and 2% CaSx treatments, soil catalase activities kept declining in the first 15 days and started to rise afterward. At the end of the experiment (Day 55), soil catalase activities in C1 and C2 had recovered to 0.27 and 0.24 mL (0.1mol/L KMnO4)−1 h−1 g−1, respectively, which were still significantly lower than that in CK (p<0.05). Dynamics of soil catalase activity in C5 was different from C1 and C2. It kept declining in the first 30 days to the minimum of 0.12 mL (0.1mol/L KMnO4)−1 h−1 g−1, and remained stable at this level until the end of the experiment without any recovery.

3.3. Dynamics of soil microbial carbon utilizing capability

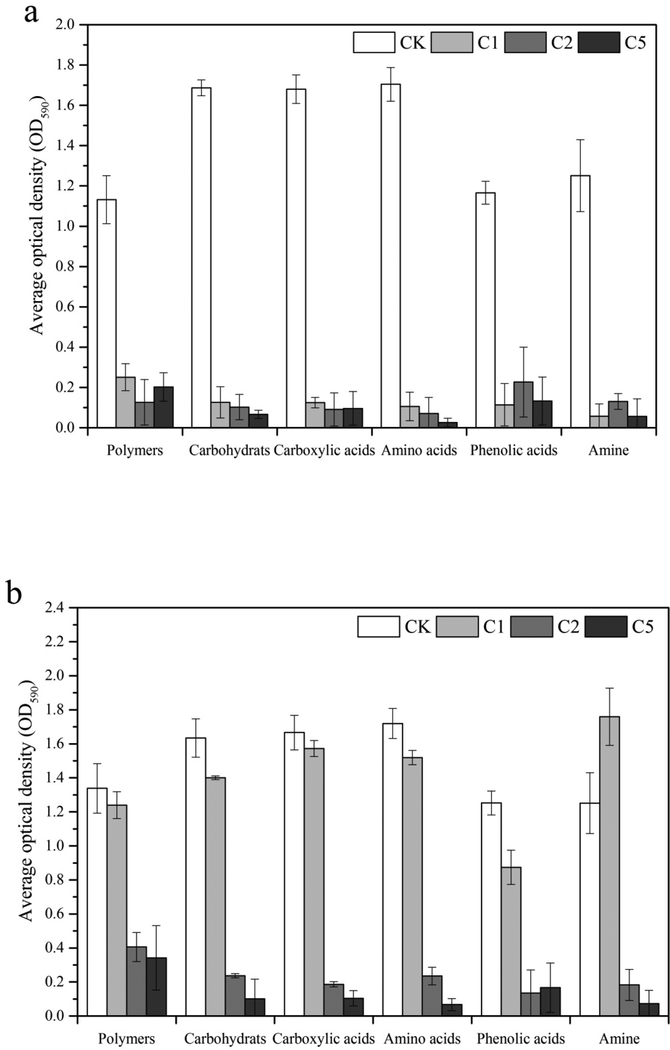

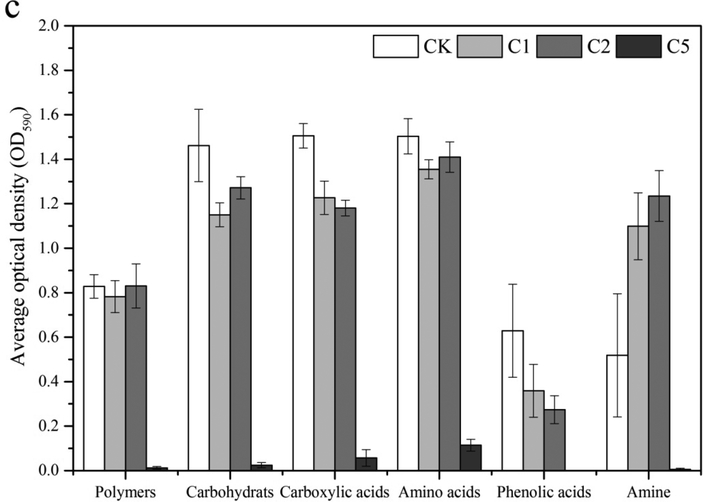

Thirty-one of the commonly used carbon sources in the Biolog EcoPlates were classified into 6 categories including carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, polymers, amino acids, phenolic acids and amines. Kinetic effects of different CaSx dosages on soil microbial carbon utilization capability are shown in Fig. 4. On Day 3, microbial utilization of all the six carbon substrate categories was significantly inhibited in all the CaSx treatments relative to CK (Fig. 4a). With increased incubation time, microbial utilization of all six carbon substrate categories in the 1% CaSx treatment started to show a significant increase on Day 30, while 2% and 5% CaSx treatments had no obvious recovery (Fig. 4b). On Day 55, all the categories of carbon substrates except phenolic acid significantly recovery in both 1% and 2% CaSx treatments, but not in the 5% CaSx treatment.

Fig. 4.

Dynamic changes of soil microbial carbon utilization capacity under different doses of CaSx amendment (a: 3 days, b: 30 days, c: 55 days)

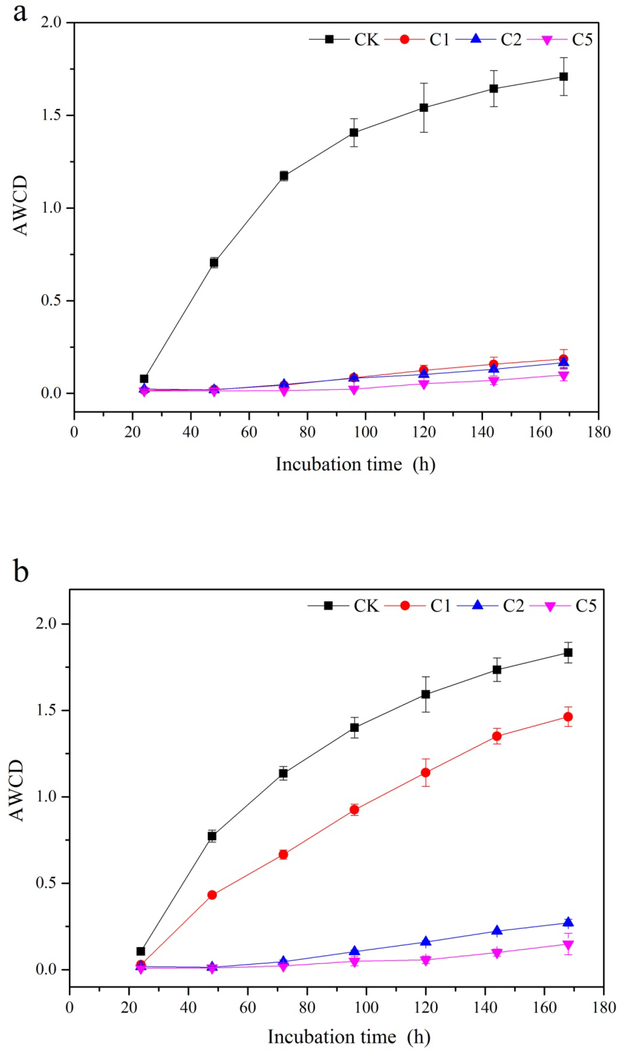

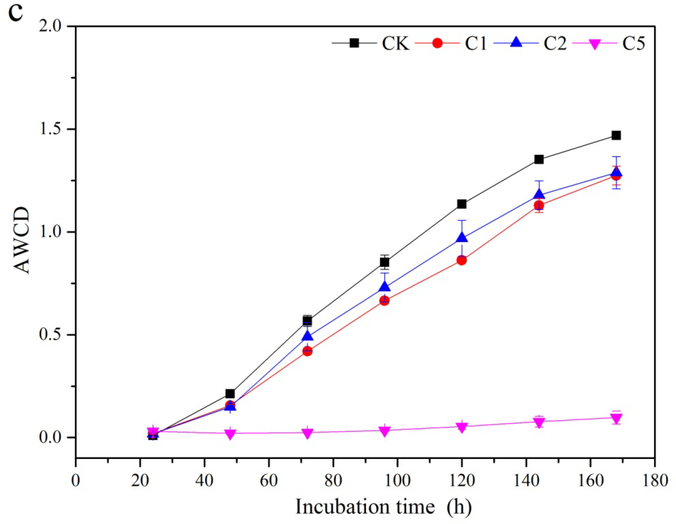

3.4. Dynamics of soil microbial community diversity

AWCD of Biolog EcoPlates was used as an indicator of soil microbial metabolic activity. Variation of AWCD with incubation time is presented in Fig. 5. Three days after CaSx application, AWCD in all the CaSx amended groups decreased significantly (Fig. 5a). On Day 30, AWCD in C1 showed an obvious enhancement relative to C2 and C5, but still significantly lower than CK (Fig. 5b). On Day 55 of CaSx amendment, AWCD in both 1% and 2% CaSx treatments increased significantly to near the level of CK, while AWCD in C5 had no obvious change during the incubation (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Dynamic changes of AWCD value of soil microbial community under different doses of CaSx amendment (a: 3 days; b: 30 days. C: 55 days)

The effects of different CaSx dosages on soil microbial community diversity, as reflected by Shannon, Simpson and Richness indices, are listed in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the Shannon, Simpson and Richness indices decreased significantly 3 days after CaSx amendment, and the differences of these indices among various CaSx dosages were not considerable. On Day 30, the Shannon, Simpson and Richness indices in 1% and 2% CaSx treatments increased significantly compared to Day 3, but still lower than CK. On Day 55, the Shannon, Simpson and Richness indices in 1% and 2% CaSx treatments had recovered to the level of CK (p<0.05), while none of these indices in 5% CaSx treatment showed any enhancement during the incubation.

Table 1.

Dynamic changes of soil microbial community diversity under different doses of CaSx amendments

| Sampling time(d) | Treatment | Shannon index(H) | Simpson index(D) | Richness index(R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | CK | 3.30±0.04 a | 26.30±0.85 a | 28.00±1.00 a |

| C1 | 2.53±0.17 b | 10.75±2.06 b | 9.67±3.21 b | |

| C2 | 1.97±0.60 b | 6.25±4.46 b | 6.00±2.65 bc | |

| C5 | 2.30±0.13 b | 7.59±1.34 b | 4.67±2.31 c | |

| 30 | CK | 3.32±0.35 a | 26.52±0.84 a | 29.00±1.73 a |

| C1 | 3.19±0.01 ab | 22.29±0.38 b | 25.33±0.58 a | |

| C2 | 2.81±0.15 b | 14.40±2.57 c | 13.67±2.89 b | |

| C5 | 2.21±0.40 c | 7.39±2.85 d | 7.00±3.61 c | |

| 55 | CK | 3.22±0.04 a | 23.67±1.21 a | 25.00±1.00 a |

| C1 | 3.22±0.05 a | 23.49±1.19 a | 26.67±1.53 a | |

| C2 | 3.16±0.03 a | 22.04±0.79 a | 24.33±0.58 a | |

| C5 | 2.11±0.16 b | 6.20±0.75 b | 5.33±0.58 b | |

Different letters in the Table indicate significant differences in the data in each column (p<0.05).

4. Discussion

The migration and transformation of heavy metals in polluted soil and sediment can be hindered by stabilization techniques based on amendments of suitable immobilizing agents. Adsorption of heavy metals on mineral surfaces, formation of stable complexes with organic ligands, surface precipitation and ion-exchange are identified as the main mechanisms responsible for the reduction of the metal mobility, leachability and bioavailability. The key to the control and remediation of heavy metal polluted wetland soil is the screening and characterizing of proper stabilization agents, including clay minerals, lime, red mud, biochar and CaSx, etc. (Bradl, 2004; Garau et al., 2007; Luce et al., 2017; Qiao et al., 2017).

4.1. Effects of CaSx on soil pH and metal bioavailability

In this study, within the first 15 days after different doses (1%, 2% and 5%) of CaSx addition, soil pH was significantly enhanced compared to the CK, and the level of pH increase showed a positive correlation with the dosage of CaSx (Fig. 1). This is mainly due to the original physico-chemical features of CaSx synthesized in this research. CaSx is a dark orange solution, with an alkaline pH (pH=11.0). It may contain various chain species including hepta-, octa-, and nano-sulphide with a pH ranging from 6.0 to 11.0 (Gun et al. 2004; Kamyshny et al. 2007). CaSx solution can enhance soil pH rapidly and significantly as soon as it interacts with the soil solid or liquid components. On the other hand, CaSx solution is unstable in soil and water environments containing O2 and CO2. With increased incubation time, CaSx decomposes rapidly in the soil with the participation of O2 and CO2, producing H2S, CaCO3, CaSO4, and solid sulphur particles. The reaction equations are listed as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

In soil or wastewater containing heavy metals, the immobilization reactions can be explained as:

| (8) |

| (9) |

Here, M represents the heavy metal cations, MS represents the precipitated metal sulphides (Dahlawi and Siddiqui, 2017). As the reaction goes on, heavy metals in the soil are stabilized in the form of MS precipitation, while H+ also accumulated in the soil, causing decreasing soil pH at equilibrium. Our results are in line with Chryosochoou et al. (2010), who have reported that within the first 60 days after CaSx applied to Cr (VI) polluted soil, soil pH was initially enhanced from 6.0 to 11.0 and gradually declined to 8.0 to 8.5 within one year.

In this research, after CaSx amendment to the soil, DTPA extractable Cd concentration in the soil decreased significantly compared to CK. Moreover, the decreasing level of DTPA extractable Cd concentration in the soil was inversely correlated with the CaSx dosage (Fig. 2). According to the literatures, appropriate dosage of CaSx amendment could chemically react with heavy metals in the soil, and produces stable metal sulfide or precipitation of hydroxide, which can reduce the mobility of heavy metal (Aratani et al., 1979; Chrysochoou et al., 2010; Maletić et al., 2015; Dahlawi and Siddiqui, 2017). However, excessive dosage of CaSx amendment may initiate the formation of a soluble metal ion complex [MSx]n-, thus causing the dissolution and re-mobilization of metal cations from the precipitated compounds (Li, 2014). In this research, 1% CaSx amendment was deemed as the appropriate dosage, which brings a continuous stabilization effect on Cd in the soil. Higher concentration (2% and 5%) of CaSx amendment resulted in significantly weaker Cd stabilization effects than 1% CaSx treatment. The excessive CaSx may react with Cd and produce soluble complexes of [CdS2]2-, which enhances the mobilization and migration of Cd in the wetland soil. However, further analysis for Cd speciation in the soil are needed, with the utilization of synchrotron-based μXRD, μXRF and μXANES techniques. Likewise, investigation of lower (<1%) CaSx amendment levels or multiple lower CaSx amendment levels on Cd immobilization would help clarify the appropriate soil dosage.

4.2. Effects of CaSx on soil microbial enzymatic activities

Although a considerable body of work exists concerning the effects of CaSx on the stabilization of heavy metals in soil and wastewater, there are few reports regarding the impacts of CaSx on soil environmental quality and ecosystem functions. Soil enzymatic activity is an important indicator for accessing the status of soil environmental quality. For example, urease is an essential soil enzyme that catalyzes urea hydrolysis into ammonia and carbonic acid. It plays an important role in the soil nitrogen cycling driven by soil microorganisms (Garau et al., 2007; Bhaduri et al., 2016). Catalase is an anti-oxidative enzyme, which directly converts H2O2 to H2O and O2 (Willekens et al., 1997). Changes of catalase activity in the soil indicates the occurrence of oxidative stress induced by various environmental stresses, including soil contamination by heavy metals and other hazardous pollutants (Shrestha et al.,2013; Wyrwicka and Urbaniak, 2016). In this research, within the early stage (0–15 day) after CaSx addition (Fig. 3a), soil urease and catalase activities in all CaSx treatments were significantly declined compared to CK, indicating considerable acute toxicity of CaSx to soil microbial activities in N cycling and oxidative stress. Equations (6) and (7) demonstrate that after CaSx was amended to the soil, H2S and S0 were produced concurrently with the stabilizing of heavy metals in the soil. However, H2S and S0 may also inhibit soil microbial activities and soil ecosystem functions to some extent (Aratani et al., 1979; Dahlawi and Siddiqui, 2016). Dorman et al. (2002) reported that H2S could directly inhibit the activity of cytochrome oxidase which is a key enzyme in mitochondrial respiration, while S0 could oxidize cytochrome b and produce H2S, causing further cell oxidative damage. Moreover, the inhibited enzyme activity shows a significant dosage-dependent effect. In this research, at the early stage after CaSx addition (0–15 day), the decreasing level of soil urease and catalase was positively correlated with the increasing of CaSx dosage. As the remediation time increased, urease and catalase activities in 1% and 2% CaSx treatments showed significant increase, indicating the inhibition to soil microbial activity had been alleviated. However, urease and catalase activities in 5% CaSx treatment showed no recovery from the initial exposure, indicating an irreversible damage to microbial activities (Fig. 3b & 3c).

4.3. Effects of CaSx on soil microbial metabolic and community diversity

Carbon source utilization capability has been shown to be a satisfactory indicator of describing microbial metabolic profile and soil environmental quality, because it reflects the potential of microbes to respond promptly to environmental changes (Garland and Mills,1991; Yao et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2015). Biolog EcoPlate is a quick, effective, and inexpensive method used to detect the dynamic variation of microbial metabolic and community diversity in soil, especially in contaminated soil (Sprocati et al. 2014; Guo et al., 2015). Although many studies have found that CaSx had high-efficiency on the stabilization of heavy metals (Cr, Pb, Cu and Ni) in soil, few researches are available on the environmental effects of CaSx amendments to coastal wetland soils. According to a USEPA toxicity report for direct human exposure, CaSx has a high pH around 11.5, which may cause irreversible damage to the eyes and light corrosion to the skin upon contact (USEPA, 2005). In this study, we report for the first time the soil microbial carbon utilization capability (Fig. 4), microbial metabolic diversity indicated by AWCD (Fig. 5), and microbial community diversity indicated by Shannon, Simpson and Richness indices (Table 1) were significantly decreased in the CaSx treatments compared to CK at the initial stage of the incubation. The above decreasing levels are closely related to the CaSx dosage. Bailey et al. (2012) also reported that CaSx could significantly inhibit the growth of specific bacterial strain Shewanella oneidensis, and a dose dependent effect was also observed. However, in the mid and later stage of incubation, the adverse effects of CaSx amendment are alleviated, as evident by the recovery of soil microbial metabolic and community diversity from Day 30. This result is consistent with Maletić et al. (2015), who reported that the addition of CaSx could not only effectively stabilize metal contaminated soils, but also reduce the microbial toxicity of heavy metal in the pore water of soil. Considering cost feasibility, the price of commercially available CaSx (500 $/t) is slightly more expensive than biochar (300 $/t); however, the recommended effective dose for biochar is 5%, which is 5-fold greater than the effective CaSx recommended amendment rate of 1%. Taking cost and efficiency into account, CaSx can be considered as an economically and environmentally friendly amendment for the in-situ stabilization of Cd contaminated wetland soil.

5. Conclusions

The stabilizing effects and environmental impacts of CaSx amendments in Cd polluted wetland soil were investigated individually in this study. CaSx could significantly decrease the bioavailability and microbial toxicity of Cd in the soil, thus reduced the environmental risk of the Cd in the wetland soil ecosystem. To our knowledge, this is the first report that assessing the Cd stabilizing efficiency and environmental impacts in wetland soil using CaSx. Results from this study should provide useful scientific evidence for the development of in-situ remediation ameliorants and technologies for heavy metal polluted wetland soils.

Acknowledgements

The current research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFE0106400), the National High Technology Research and Development Program (2012AA06A204–4, 2013AA06A211–4), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41230858). Although EPA contributed to this article, the research presented was not performed by or funded by EPA and was not subject to EPA’s quality system requirements. Consequently, the views, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect or represent EPA’s views or policies.

References

- Abad-Valle P, Álvarez-Ayuso E, Murciego A, Pellitero E, 2016. Assessment of the use of sepiolite amendment to restore heavy metal polluted mine soil. Geoderma 280, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aratani T, Yasuhara S, Matoba H, Yano T, 1979. Continuous Removal of Heavy Metals by the Lime Sulfurated Solution (Calcium Polysulfide) Process. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 52(1), 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KL, Tilton F, Jansik DP, Ergas SJ, Marshall MJ, Miracle AL, Wellman DM, 2012. Growth inhibition and stimulation of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 by surfactants and calcium polysulfide. Ecotoxicology & Environmental Safety 80(2), 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao K, Shen J, Sapkota A, 2017. High-resolution enrichment of trace metals in a west coastal wetland of the southern Yellow Sea over the last 150 years. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 176, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaduri D, Saha A, Desai D, Meena HN, 2016. Restoration of carbon and microbial activity in salt-induced soil by application of peanut shell biochar during short-term incubation study. Chemosphere 148(4), 86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradl HB, 2004. Adsorption of heavy metal ions on soils and soils constituents. Journal of Colloid & Interface Science 277(1), 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun B, Böckelmann U, Grohmann E, Szewzyk U, 2010. Bacterial soil communities affected by water-repellency. Geoderma 158(3–4), 343–351. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysochoou M, Ferreira DR, Johnston CP, 2010. Calcium polysulfide treatment of Cr(VI)-contaminated soil. Journal of Hazardous Materials 179(1–3), 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysochoou M, Ting A, 2011. A kinetic study of Cr(VI) reduction by calcium polysulfide. Science of the Total Environment 409(19), 4072–4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Böddeker S, Hoelzmann P, Thuyên LX, Huy HD, Nguyen HA, Richter O, Schwalb A, 2017. Ecological risk assessment of a coastal zone in Southern Vietnam: Spatial distribution and content of heavy metals in water and surface sediments of the Thi Vai Estuary and Can Gio Mangrove Forest. Marine Pollution Bulletin 114 (2), 1141–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlawi SM, Siddiqui S, 2017. Calcium polysulphide, its applications and emerging risk of environmental pollution - a review article. Environmental Science & Pollution Research 24(1), 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman DC, Moulin FJ, Mcmanus BE, Mahle KC, James RA, Struve MF, 2002. Cytochrome oxidase inhibition induced by acute hydrogen sulfide inhalation: correlation with tissue sulfide concentrations in the rat brain, liver, lung, and nasal epithelium. Toxicological Sciences 65(1), 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan WH, Zhang B, Chen JS, Zhang R, Deng BS 2006. Pollution and potential biological toxicity assessment using heavy metals from surface sediments of Jinzhou Bay. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 26(6), 1000–1005 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Fruchter J, 2002. In situ treatment of chromium-contaminated groundwater. Environmental Science & Technology 36(23), 464A–472A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garau G, Castaldi P, Santona L, Deiana P, Melis P, 2007. Influence of red mud, zeolite and lime on heavy metal immobilization, culturable heterotrophic microbial populations and enzyme activities in a contaminated soil. Geoderma 142(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Garland J, Mills A, 1991. Classification and characterization of heterotrophic microbial communities on the basis of patterns of community-level sole-carbo-source utilization. Applied and Environment Microbiology 57, 2351–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guemiza K, Coudert L, Metahni S, Mercier G, Besner S, Blais J, 2017. Treatment technologies used for the removal of As, Cr, Cu, PCP and/or PCDD/F from contaminated soil: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 333, 194–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gun J, Modestov A, Kamyshny A, Ryzkov D, Gitis V, Goifman A, 2004. Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Aqueous Polysulfide Solutions. Microchimica Acta 146(3–4), 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Guo PP, Zhu LS, Wang JH, Wang J, Liu T, 2015. Effects of alkyl-imidazolium ionic liquid [Omim]Cl on the functional diversity of soil microbial communities. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 22(12), 9059–9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoš P, Vávrová J, Herzogová L, Pilařová V, 2010. Effects of inorganic and organic amendments on the mobility (leachability) of heavy metals in contaminated soil: a sequential extraction study. Geoderma 159(3–4), 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang LL, Han GM, Lan Y, Liu SN, Gao JP, Yang X, Meng J, Chen WF, 2017. Corn cob biochar increases soil culturable bacterial abundance without enhancing their capacities in utilizing carbon sources in Biolog Eco-plates. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 16(3), 713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge-Mardomingo I, Soler-Rovira P, Casermeiro MÁ, Cruz MT, Polo A, 2013. Seasonal changes in microbial activity in a semiarid soil after application of a high dose of different organic amendments. Geoderma 206(9), 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kameswari KSB, Pedaballe V, Narasimman LM, Kalyanaraman C, 2015. Remediation of chromite ore processing residue using solidification and stabilization process. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 34(3), 674–680. [Google Scholar]

- Kamyshny A, Gun J, Rikzov D, Voitsekovski T, Lev O, 2007. Equilibrium distribution of polysulfide ions in aqueous solutions at different temperatures by rapid single phase derivatization.[J]. Environmental Science & Technology 41(7), 2395–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koptsik GN, 2014. Modern approaches to remediation of heavy metal polluted soils: A review. Eurasian Soil Science 47(7), 707–722. [Google Scholar]

- Kopittke PM, Dalal RC, Menzies NW, 2017. Changes in exchangeable cations and micronutrients in soils and grains of long-term, low input cropping systems of subtropical Australia. Geoderma 285, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Lee JS, Choi YJ, Kim JG, 2009. In situ stabilization of cadmium-, lead-, and zinc-contaminated soil using various amendments. Chemosphere 77(8), 1069–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko LM, Galitskii AA, Kosenko VV, Sagidullin AK, 2015. Development of semi-industrial synthesis of calcium polysulfide solution and determination of the content of sulfide ions in solution. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 88(9), 1403–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, 2014. Innocuous treatment of wastewater containing mercury by polysulfide complex reactions. Polyvinyl Chloride 42(5), 39–43. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Liu J, Jiang C, Wu M, Song RS, Gui RY, Jia JX, Li ZP, 2017. Improved nutrient status affects soil microbial biomass, respiration, and functional diversity in a Lei bamboo plantation under intensive management. Journal of Soils & Sediments 17(4), 917–926. [Google Scholar]

- Luce MS, Ziadi N, Gagnon B, Karam A, 2017. Visible near infrared reflectance spectroscopy prediction of soil heavy metal concentrations in paper mill biosolid- and liming by-product-amended agricultural soils. Geoderma 288, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mahabadi AA, Hajabbasi MA, Khademi H, Kazemian H, 2007. Soil cadmium stabilization using an Iranian natural zeolite. Geoderma 137(3–4), 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Maletić SP, Watson MA, Dehlawi S, Diplock EE, Mardlin D, Paton GI, 2015. Deployment of microbial biosensors to assess the performance of ameliorants in metal-contaminated soils. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 226(4), 85. [Google Scholar]

- Pan K, Wang WX 2012. Trace metal contamination in estuarine and coastal environments in China. Science of the Total Environment 421–422, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J, Sun H, Luo X, Zhang W, Mathews S, Yin XQ, 2017. EDTA-assisted leaching of Pb and Cd from contaminated soil. Chemosphere 167, 422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KR, Delaune RD, Reddy KR, Delaune RD, 2009. Biogeochemistry of wetlands: science and applications. Biogeochemistry of Wetlands Science & Applications 73(2), 1779. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha B, Martinezb VA, Cox SB, Green MJ, Li S, Canas-Carrell JE, 2013. An evaluation of the impact of multiwalled carbon nanotubes on soil microbial community structure and functioning. Journal of Hazardous Materials 261, 188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprocati AR, Alisi C, Tasso F, Fiore A, Marconi P, Langella F, Haferburg G, Nicoara A, Neagoe A, Kothe E, 2014. Bioprospecting at former mining sites across Europe: microbial and functional diversity in soils. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 21, 6824 10.1007/s11356-013-1907-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udovic M, Lestan D, 2012. EDTA and HCl leaching of calcareous and acidic soils polluted with potentially toxic metals: remediation efficiency and soil impact. Chemosphere 88(6), 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 2005. Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Other Toxic Substances.Reregistration eligibility decision for inorganic polysulfides. ListD-case no. 4054. September 30.

- Willekens H, Chamnongpol S, Davey M, Schraudner M, Langebartels C, VanMontagu M, Inze D, VanCamp W, 1997. Catalase is a sink for H2O2 and is indispensable for stress defence in C-3 plants. EMBO J. 16, 4806–4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrwicka A, Urbaniak M, 2016. The Different Physiological and Antioxidative Responses of Zucchini and Cucumber to Sewage Sludge Application. PLoS ONE 11(6), e0157782 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157782 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Wang TY, Wang JH, Lu AX, 2017. Occurrence, speciation and transportation of heavy metals in 9 coastal rivers from watershed of Laizhou Bay, China. Chemosphere 173, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahikozawa K, Aratani T, Ito R, Sudo T, Yano T, 1978. Kinetic studies on the lime sulfurated solution (calcium polysulfide) process for removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 51(2), 613–617. [Google Scholar]

- Yao HY, Xu JM, Huang CY, 2003. Substrate utilization pattern, biomass and activity of microbial communities in a sequence of heavy metal-polluted paddy soils. Geoderma 115, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XM, Xia DS, Song B, Chen TB 2017. Review on soil cadmium study and risk assessment in Guangxi. Journal of Natural Resources 32(7), 1256–1270 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]