Abstract

Finger millet is being recognized as a potential future crop due to their nutrient contents and antioxidative properties, which are much higher compared to the other minor millets for providing health benefits. The synthesis of these nutritional components is governed by the expression of several gene(s). Therefore, it is necessary to characterize these genes for understanding the molecular mechanisms behind de novo synthesis of nutrient components. Apart from this, these important compounds could also serve as candidate genes for imparting stress tolerance in other crop plants also. In the present study, effort has been made to identify genes involved in Ascorbate–Glutathione cycle (Halliwell–Asada Pathway) and related pathway genes for elucidating its role in antioxidative potential mechanism through transcriptome data analysis. APX, DHAR, MDHAR, GR, and SOD have been identified as the key genes of the pathway in two genotypes GP-1 (low Ca2+) and GP-45 (high Ca2+) of finger millet with reference to rice as a model system, besides, 30 putatively expressed genes/proteins were also investigated. Furthermore, the sequences of identified genes were analyzed systematically; gene ontology (GO) annotation and enrichment analysis of assembled unitranscripts were also performed using Blast2GO. As a result, 49 GO terms, 5 Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, and 2 KEGG pathway maps were generated. GO results revealed that these genes are mainly involved in two biological processes (BP), viz., oxidation–reduction process (GO:0055114) and cellular oxidant detoxification (GO:0098869), and showed oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491). KEGG analysis showed that APX, DHAR, MDHAR, and GR are directly connected to biosynthetic pathways of secondary metabolites, mainly polyphenolic compounds (flavonoid, tannin, and lignin) involved in glutathione metabolism (KEGG:00480) and ascorbate and aldarate metabolism (KEGG:00053). While SOD, is indirectly connected and also has significant medicinal attributes and antioxidant properties. Moreover, Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) values were also calculated for expression analysis and found that the FPKM values of genes present in GP-1 are higher than that of GP-45. Thus, GP-1 genotype was found to have higher stress regulated gene expression in comparison to GP-45. Taken together, the present transcriptome-based investigation unlocks new avenues for systematic functional analysis of novel ROS scavenging candidate genes that could be effectively applied for improvising human health and nutrition.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1511-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Finger millet, Halliwell–Asada pathway, Transcriptome data, GO annotation, Enrichment analysis

Introduction

Finger millet is one of the important cereal crops, cultivated mostly in arid and semiarid areas of Africa and India (Seetharam et al. 1986). Major finger millet producing countries include Africa, India, China, Uganda, and Nepal (FAOSTAT 2004). It belongs to the grass family (Poaceae) and is more commonly known as Ragi or Madua in Southern India and Nachni in Northern India (Obilana and Manyasa 2002). It is more popular in several countries with distinct name such as rapoko in South Africa and dagusa in Ethiopia (Ignacimuthu and Ceasar 2012). It is an agronomically sustainable crop, which can be grow on marginal lands with a few efforts and requires little water and other economic resources. In the world, it ranks fourth in production and importance among millets after pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), proso millet (Panicum miliaceum), and foxtail millet (Setaria italica).

Rice and wheat are the staple crops which might be responsible for providing food security, but the cost of their production in economic and environmental terms is significantly high, while finger millet provides manifold utilities including fibers, vitamins, and minerals which are produced at only a fraction of the cost of rice or wheat (Avashthi et al. 2017; Tiwari et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2016). Nutritionally, finger millet is an excellent source of calcium and other nutrients especially phytochemicals (polyphenols), carbohydrates, proteins, minerals, and dietary fibers. Some of the finger millet genotypes have been analyzed and found to have very high calcium content in the range of 450 mg/100 g (Panwar et al. 2010; Nath et al. 2010; Kumar et al. 2014; Chinchole et al. 2017; Kokane et al. 2018; Gupta et al. 2018). On the basis of calcium richness, finger millet can be used as preventive drug against osteoporosis. In comparison of other millets and major cereal crops, finger millet is also enriched in the other micronutrients (trace elements) such as potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, manganese, iron, zinc, and molybdenum (Gopalan et al. 1999; Kumar et al. 2015a, b). Finger millet is considerably rich in carbohydrates and vitamins especially folic acid and vitamin E (Gopalan et al. 2004). Folic acid is a form of vitamin B that plays an important role in the formation of red blood cells which carry oxygen and reduce the risk of anemia. It is a major problem in old age persons where the production rate of red blood cells slows down. Finger millet also shows anticancerous and antidiabetic properties, mainly due to its high content of polyphenols that indicates antioxidant activity (Graf and Eaton 1990; Chethan and Malleshi 2007; Chandrasekara and Shahidi 2010, 2011a, b). In the past few years, dietary polyphenols have received considerable attention from consumers and nutritional scientists for their tremendous health benefits like reduced risk of osteoporosis, cancer, aging, diabetes, and neuro-degenerative diseases (Kaur and Kapur 2001; Scalbert et al. 2005; Tsao 2010). The seed coat of finger millet grain contains high amount of phenolic compounds including derivatives of benzoic acid such as gallic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, protocatechuic acid, syringic acid, and vanillic acid which have been reported to exhibit important therapeutic effects and antioxidant activity (Banerjee et al. 2012). In recent trials with the millets, finger millet along with some other millets has been reported to contain several important bioactive compounds having antioxidative, antiinflammatory, and antimicrobial properties (Sripriya et al. 1996; Anthony et al. 1998; Kumari and Sumathi 2002; Rajasekaran et al. 2004; Shahidi and Chandrasekara 2013).

The antioxidant compounds are also involved in plant defense against a spectrum of environmental stresses. The complex antioxidative defense system consists of a number of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), guaiacol peroxidase (GPX), and the enzymes of Ascorbate–Glutathione (AsA–GSH) cycle such as ascorbate peroxidase (APX), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR), and glutathione reductase (GR), along with an array of non-enzymatic molecules like ascorbate, glutathione, etc. (Gill and Tuteja 2010; Miller et al. 2010; Gill et al. 2011; Noctor and Foyer 1998). These constitute the protective machinery, because they balance the speed of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and their elimination by scavenging the free oxygen radicals (Zhang et al. 2013). In plants, the role of ascorbate peroxidase and glutathione reductase in H2O2 scavenging has been well established (Bowler et al. 1992). Oxidation is only a chemical process that produces free radicals. ROS, such as superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (HO•), formed by the partial reduction of oxygen (Halliwell 2006). The AsA–GSH recycling pathway also referred to as Halliwell–Asada Pathway which detoxifies H2O2. In plants and animals, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated during mitochondrial electron transport, oxidative metabolism, as well as in cellular response to xenobiotics, the production of free radicals (ROS) in excess amount causes cell damages such as oxidation of proteins, damage to nucleic acids, peroxidation of lipids, activation of programmed cell death pathway, and ultimately leading to the cell death which refers to oxidative stress (Shah et al. 2001; Mittler 2002; Verma and Dubey 2003; Meriga et al. 2004; Sharma and Dubey 2005; Maheshwari and Dubey 2009). Based on these facts, finger millet increased the activities of antioxidant enzymes like catalase, peroxidase, and reductase. The results of oxidative stress are very serious, which cause various diseases such as diabetes, cancer, neuro-degeneration, aging, and macromolecular damage. Antioxidants, mainly polyphenols, are the key component to reduce oxidative stress (Mishra et al. 2011; Srivastava and Dubey 2011). It protects human body from free radical damage by improving immunity.

In the present study, we tried to perform experiments on transcriptome data to find antioxidative potential genotype between GP-1 (low Ca2+) and GP-45 (high Ca2+) of finger millet. High-throughput de novo assembly of RNA-seq data have become known as powerful and cost-efficient tools, when no reference genome is available (Zhao et al. 2011). With the availability of complex RNA-Seq data of finger millet, it has become possible to identify novel genes that can differentiate the both genotypes in terms of antioxidant properties or stress tolerance ability. The availability of defense providing nutraceutical properties in finger millet will helpful to make superior among all cereal crops (Kumar et al. 2016a, b). In view of above facts, there is a need of computational approach to decipher the complexity of transcriptome data available for identification of genes involved in AsA–GSH cycle and related pathway genes for elucidating its role in antioxidative potential in finger millet.

Materials and methods

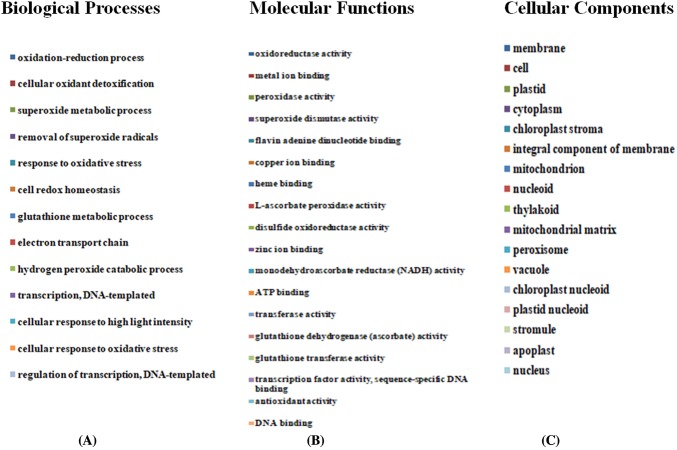

Data collection and de novo transcriptome assembly

The developing spikes transcriptome data of four stages, viz., S1 (spike emergence), S2 (pollination), S3 (milky), and S4 (seed maturation) of finger millet GP-45 (high-seed calcium) and GP-1 (low-seed calcium) genotypes, sequenced by the scientists from G. B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology Pantnagar, India using Illumina HiSeq 2000 was taken in the present study. These are the biological replicates, because we performed the same test on two different samples of the same organism. This is publically available at SRA (Sequence Read Archive) database of NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information with accession number SRR1151079 and SRR1151080 for further investigation (Kumar et al. 2015a, b; Singh et al. 2014). Furthermore, the downloaded raw data were subjected to FastQC for quality control. In addition to sequence error correction and accuracy improvement of the de novo assembled data, low-quality (high probability of errors) reads and adapter sequences were trimmed from the sequencing reads using software package Trimmomatic version 0.36. Specifically, sequences were trimmed at both 5′ and 3′ ends with constant parameters (ILLUMINACLIP = barcodes.fa:2:40:15, MINLEN = 25, SLIDINGWINDOW size = 4). Furthermore, de novo RNA-Seq assembly of high-quality reads was done using the Trinity software (https://github.com/trinityrnaseq/trinityrnaseq/releases) to generate a set of non-redundant transcript with default parameters (k-mer length = 25, group_pairs_distance = 500, path_reinforcement_distance = 75, min_glue = 2). Approximately, a total of 4.3 GB (Gigabyte) and 4.8 GB sequence data were generated from the low seed calcium (GP-1) and high seed calcium (GP-45) genotype, respectively. After sequencing, high-quality assembled reads were obtained in FASTQ format; further resulted format is converted into FASTA format using FASTX-Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) and shrinks its size from GB to MB i.e. 127 MB (GP-45) having 120,130 contigs and 99.6 MB (GP-1) having 109,128 contigs, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the analysis from sample collection to gene(s) identification and annotation

Sequence Retrieval and Identification of Halliwell–Asada Pathway Genes in Finger Millet using Rice as a model system

To identify Halliwell–Asada or Ascorbate–Glutathione pathway genes from transcriptome data of finger millet in both genotypes GP-1 and GP-45, Coding Sequence (CDS) of rice ROS-producing/scavenging genes, viz., APX, MDHAR, DHAR, GR, and SOD, were retrieved from TIGR: Rice Genome Annotation Project (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) database. For identification of gene contigs, ROS genes of rice were taken as query sequences and searched in whole transcriptome data of both genotypes using standalone program BLASTn (Altschul et al. 1990). Afterwards, each gene gave around 3–10 contigs/hits in the form of comp IDs, Therefore, an excel sheet of all ROS genes was made which influx a huge file of data. Then various filters (E value and identity) were applied to remove data redundancy. Finally, the hits with minimum expected value and maximum identity were selected. Furthermore, comp ID was used to fetch contig sequences from transcriptome data using local perl script for both genotypes separately.

Contig assembly

Retrieved contig sequences have two types of strands, i.e., positive (+) and negative (−) strand, and these negative strands were converted into its reverse or positive strand using reverse complementary tool offered by Sequence Manipulation Suite (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/rev_comp.html). Afterwards, these pre-processed high-quality contigs were merged and input into the CLC Genomics Workbench (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/clc-genomics-workbench/) with default parameters for assembling into full-length gene through de novo algorithm. Further optimization of assembled contigs (full-length gene) was done using Blastx with the close relative crop of finger millet, i.e., rice (Oryza sativa) with an e value of 1e−6. The typical threshold or a good E value for a BLAST search is e−5= (10−5) or lower (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/tutorial/Altschul-1.html).

Structural and functional annotation of identified genes

ORF prediction

All assembled contig sequences were subjected to NCBI’s ORF finder tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) to predict the Open Reading Frame (ORF) or coding DNA sequence (CDS). ORF of longest length (nucleotide and protein sequence) was selected for structural and functional annotation.

Analysis of conserved motif

To explore the structural divergence among the genes of Eleusine coracana reactive oxygen species (EcROS), conserved motif was investigated in the ORFs encoded proteins. Complete amino acid sequences of these genes were subjected to MEME (Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation; http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) using advanced options with slightly changed parameters: (1) optimum motif width was set from 6 to 250; (2) identifying the maximum number of motifs (50) was selected.

Domain analysis and characterization of physicochemical properties

The presence of conserved domain in EcROS proteins was analyzed by employing CD Search tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi) of NCBI. After analyzing conserved domain, primary sequences of EcROS proteins were subjected to ProtParam tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/) available at ExPASy’s server. Various physicochemical properties such as aliphatic index, instability index, isoelectric point, molecular weight, and grand average hydropathy (GRAVY) were calculated (Garg et al. 2016).

Phylogenetic analysis

Full-length amino acid sequences of SOD, APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR of both genotypes of finger millet was compared. To compare these proteins, sequences were imported into MEGA7 (Kumar et al. 2016a, b) and performed multiple sequence alignments using ClustalW with the default parameters. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbor-joining method with default parameter. To validate the phylogenetic tree, bootstrap test (1000 replicates) was also performed.

Gene ontology (GO) annotation

To annotate the function of EcROS unigenes, gene ontology analysis was performed using the Blast2GO program (https://www.blast2go.com/). The amino acid sequences of EcROS were imported into Blast2GO with default parameters to execute three-step process of functional annotation, viz., (1) BLASTp against the non-redundant protein database of NCBI, UniProt/Swiss-Prot, Cluster of Orthologous Group (COG) of proteins, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was performed with cutoff E value of 1e−5 and retrieved protein functional annotations based on sequence similarity, (2) mapping and retrieval of GO terms associated with the BLAST results were carried out, and (3) annotation of GO terms associated with each query was determined to relate the sequences to known protein function. This program assigned the GO terms to the unigenes and provides the output in three categories of GO classification namely biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular components (CC). Two more programs were also used to confirm the results of BLAST2GO, viz., AgriGO (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/) and GeneCoDis (http://genecodis.cnb.csic.es/).

Gene expression analysis

To estimate transcript abundance and identify significant changes in transcript expression between both genotypes, FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) values for each unitranscript were calculated by bedtools (http://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) and used to analyze differential gene expression. Binary alignment map (BAM) file of RNA-Seq data was used to obtain FPKM values. R package (https://www.r-project.org/) was used for construction of a heatmap.

Sequence submission

Predicted genes (30) of APX, DHAR, MDHAR, GR, and SOD from finger millet genotypes (15 from GP-45 and 15 from GP-1) were submitted to GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) of NCBI that is available publically to the scientific community for the further investigations. Submitted sequences includes, 8 APX (EcAPX1, EcAPX2, EcAPX6, and EcAPX8), 6 MDHAR (EcMDHAR, EcMDHAR4 and EcMDHAR5), 2 EcDHAR, 2 EcGR, and 12 SOD (EcSOD, EcSOD1 and EcSOD2). The assigned accession numbers of each gene are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of (non-redundant ROS-producing genes) submitted genes in NCBI and their assigned accession numbers

| S. No. | Gene | Genotype | Status | CDS length | Protein length | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | DHAR2 | GP-45 | Complete | 642 | 213 | MF872197 |

| 2. | APX8 | GP-45 | Complete | 1455 | 484 | MF872198 |

| 3. | MDHAR4 | GP-45 | Complete | 1437 | 478 | MF872199 |

| 4. | GR | GP-45 | Complete | 1659 | 552 | MF872200 |

| 5. | SOD2 | GP-45 | Partial | 492 | 163 | MF872201 |

| 6. | APX1 | GP-45 | Complete | 753 | 250 | MF872202 |

| 7. | SOD2 | GP-45 | Partial | 459 | 152 | MF872203 |

| 8. | SOD | GP-45 | Complete | 711 | 236 | MF872204 |

| 9. | SOD1 | GP-45 | Complete | 1206 | 401 | MF872205 |

| 10. | SOD2 | GP-45 | Complete | 594 | 197 | MF872206 |

| 11. | APX2 | GP-45 | Complete | 648 | 215 | MF872207 |

| 12. | MDHAR5 | GP-45 | Complete | 1481 | 493 | MF872208 |

| 13. | MDHAR | GP-45 | Complete | 1308 | 435 | MF872209 |

| 14. | SOD | GP-45 | Partial | 717 | 238 | MF872210 |

| 15. | APX6 | GP-45 | Complete | 939 | 312 | MF872211 |

| 16. | DHAR2 | GP-1 | Complete | 642 | 213 | MF872212 |

| 17. | APX8 | GP-1 | Complete | 1458 | 485 | MF872213 |

| 18. | MDHAR4 | GP-1 | Complete | 1437 | 478 | MF872214 |

| 19. | GR | GP-1 | Complete | 1659 | 552 | MF872215 |

| 20. | SOD2 | GP-1 | Partial | 492 | 163 | MF872216 |

| 21. | APX1 | GP-1 | Complete | 753 | 250 | MF872217 |

| 22. | SOD2 | GP-1 | Partial | 459 | 152 | MF872218 |

| 23. | SOD | GP-1 | Complete | 711 | 236 | MF872219 |

| 24. | SOD1 | GP-1 | Complete | 1206 | 401 | MF872220 |

| 25. | SOD2 | GP-1 | Complete | 777 | 258 | MF872221 |

| 26. | APX2 | GP-1 | Complete | 648 | 215 | MF872222 |

| 27. | MDHAR5 | GP-1 | Complete | 1491 | 496 | MF872223 |

| 28. | MDHAR | GP-1 | Complete | 708 | 235 | MF872224 |

| 29. | SOD | GP-1 | Partial | 615 | 204 | MF872225 |

| 30. | APX6 | GP-1 | Complete | 942 | 313 | MF872226 |

Results

Quality assessment and de novo assembly

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has been extensively utilized to deciphering the transcriptome profiles of plants. Here, extracted RNA from the developing spike tissue of two genotypes GP-1 and GP-45 of E. coracana was used to construct cDNA library which was then sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. A total of 64,849,478 and 72,447,518 raw paired-end reads were obtained for GP-1 and GP-45, respectively. These raw data have been deposited to NCBI’s SRA database with accession number SRR1151079 and SRR1151080 for further study. Clean reads were filtered from raw reads by removal of technical sequences including adapters, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers, ambiguous, and low-quality reads. After preprocessing and quality checking, approximately 32,424,739 and 36,223,759 clean paired-end reads (~ 7 GB) were retained in FASTQ format. All the processed clean reads were de novo assembled using the Trinity software, which generated a total of 109,218 and 120,130 non-redundant transcripts with an average length of 788.913 and 920.668 bp, and N50 of 1,191 and 1,450 bp, respectively, in GP-1 and GP-45 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Post de novo assembly statistics of finger millet genotypes GP-1 and GP-45

| Properties | GP-1 | GP-45 |

|---|---|---|

| Total reads | 32,424,739 | 36,223,759 |

| Total transcripts/contigs | 109,218 | 120,130 |

| Total assembled bases | 86,163,511 | 110,599,833 |

| Average contig length | 788.913 | 920.668 |

| Contig N50 | 1191 | 1450 |

| Percent GC | 53 | 53 |

Identification of Halliwell–Asada pathway genes

ROS-producing genes of rice were used as reference for the identification of Halliwell–Asada Pathway genes in finger millet developing spikes transcriptome data. Out of 120,130 contigs of GP-45 and 109,218 contigs of GP-1, a total of 45 and 43 contigs were found and filtered, respectively. Hits with lower E value (≤ 0.0) was considered for further analysis. These sequences were taken and imported to CLC Genomics Workbench for reducing redundancy and obtaining full-length sequences of gene by performing contig assembly. Thirty full-length genes (15 from each genotype) were found; furthermore, ORF finder, an online tool, is employed to identify the ORFs of encoding putative antioxidant (ROS-producing) protein in finger millet. Finally, we demonstrated 30 (15 from GP-1 and 15 from GP-45) non-redundant ROS-producing genes from both genotype (Table 1). It includes 8 ORFs for APXs, 6 for MDHARs, 2 for DHARs, 2 for GRs, and 12 for SODs. Furthermore, nucleotide and translated protein sequences of these genes were deposited to the GenBank database and provided publicly which can be accessed through assigned accession numbers (Table 1).

Sequence analysis

The publically accessible complete or partial protein sequences of ROS-producing genes from E. coracana L., which is expected to play critical role in antioxidants synthesis and defense responses during abiotic stresses was subjected to ProtParam tool for computation of various physicochemical properties. After determining the presence of amino acid content in the protein sequences, we have found the high content of Alanine, Glycine, and Leucine in all the sequences of APX, DHAR, MDHAR, GR, and SOD. Rest of these common ratios found a little variation like, APX showed high content of Prolamine, except APX all the sequences showed richness of Valine. On the other hand, these sequences are poor in Cysteine and Tryptophan, except GR all sequences showed poorness of Methionine, whereas MDHAR shown poorness of one more residue, i.e., Arginine. In comparison to other, the molecular weight (MW) of GR is extremely high, i.e., 59547.86 kDa in GP-1 and 59534.85 kDa in GP-45, respectively, followed by MDHAR (~ 25,000–52,000 kDa), APX (~ 23,000–52,000 kDa), SOD (~ 15,000–44,000 kDa), and DHAR (~ 23,000 kDa). The isoelectric point (pI) of an amino acid is the pH at which the net charge on protein is zero. At pI, proteins are stable and compact. The pI of all genes except, MDHAR4, MDHAR5, SOD, and APX6 indicated its acidic nature (pI < 7.0) in both genotypes. The aliphatic index (AI) is described as the relative volume of a protein occupied by aliphatic side chains such as alanine, valine, leucine, and isoleucine. It is believed as a positive factor for the enhancement of thermostability of globular proteins (Ikai 1980). Since the aliphatic index of DHAR2 was very high, i.e., (91.50) and identical in both genotypes, followed by MDHARs, SODs, GRs, and APXs, it indicates that DHAR2 might be more stable in comparison to others, for a wide range of temperatures. The instability index (II), provides an estimate regarding the stability of protein in a test tube. Those proteins having instability index (< 40) is predicted as stable, whereas a value (> 40) predicts that the protein might be unstable (Guruprasad et al. 1990; Pathak et al. 2017). The instability index of APX8, SOD1, SOD2, and APX6 was calculated as 54.73, 46.61, 48.65, and 47.98 which indicated its unstable nature; except these proteins, all proteins were found stable. The Grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) of APX8, SOD1, and APX1 was very low (i.e., − 0.513, − 0.495, and − 0.463) in comparison to others which indicate its high affinity for water. After everything else, key finding of primary structure analysis is the sequence of DHAR2, SOD2, APX1, and APX2 are of the same length and found similar physicochemical properties in both genotypes (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Structural conserved motif and domain analysis

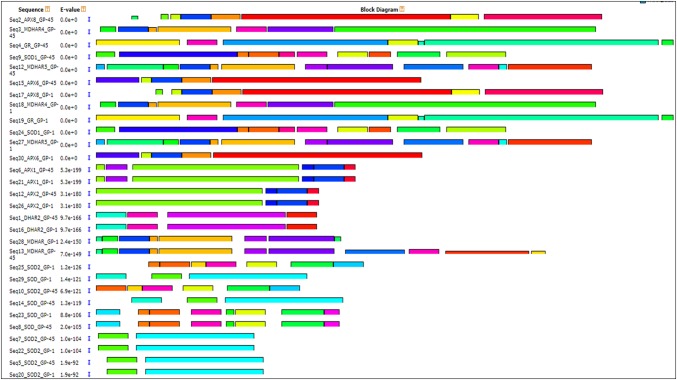

The conserved motifs present in the identified sequences were determined using MEME, revealing a total of 50 conserved motifs (Fig. 2). In both genotypes, motif 1, 3, and 7 were present in APX2, APX6, and APX8 specifying the conserved APX domain (cd00691), motif 4, 6, 11, and 18 were present in almost all MDHAR family members, specifying the conserved pyr redox 2 domain indicated by the Pfam accession number (Pfam07992). Motif 2, 5, 9, 13, and 21 specifying the conserved Sod Cu–Zn superfamily and Sod Fe–C superfamily domain designated by PLN02386 and cl27368 accession numbers. Conserved motifs 8, 16, and 23 specified the glutathione dehydrogenase domain (cl25455) and motif 8, 11, 17, and 19 specified the glutathione reductase domain (PLN02546) and were found in all DHAR and GR family proteins (Tables 3, 4).

Fig. 2.

Motifs of ROS-producing proteins (intact ORF) derived by the MEME analysis. Thirty protein sequences from both genotypes were used for motif prediction. Changed parameters are as follows: range of motif width = 6-250 amino acids and maximum number of motifs = 50

Table 3.

Conserved motif sequences of ROS-producing proteins in genotypes GP-1 and GP-45

| S. no. | p value | Motif length | Motif sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3.9e−231 | 100 | LKLIQPIKDKYPGITYADLFQLASATAIEEAGGPKIPMKYGRVDVAAPEQCPPEGRLPDAGPPSPAEHLREVFYRMGLDDKEIVALSGAHTLGRARPERS |

| 2. | 9.7e−124 | 100 | PGLHGFHIHAFGDTTNGCISTGPHFNPNNKPHGAPEDEIRHAGDLGNIVANADGVAEVTVTDLQIPLTGPNSIIGRAVVVHADPDDLGKGGHELSKSTGN |

| 3. | 6.5e−195 | 100 | MLRLAWHSAGTFDVATKTGGPFGTMKNPAEQAHGANAGLDIAIRLLEPIKEZFPTLSYGDFYQLAGVVAVEVTGGPDIPFHPGREDKPZPPPEGRLPDAT |

| 4. | 2.0e−70 | 63 | KAVVIGGGYIGMEVAAALVTNNIDVTMVFPEPHCMPRLFTPDIAEYYEEYYAQKGVKFVKGTL |

| 5. | 3.9e−45 | 41 | PTPNAISPLAFGHIPLLAIDVWEHAYYLDYKDRRPDYVSNI |

| 6. | 1.7e−57 | 57 | LPGFHTCVGSGGERLTPEWYKEKGIELILGTEIVAADLKTKTLTTATGETLTYETLI |

| 7. | 1.9e−24 | 29 | KELLKDGVFRPLLVILSKEEVAPYERPAL |

| 8. | 7.0e−17 | 29 | RESPLPEYFHLAQVWNHDFFWKSMKPEGG |

| 9. | 5.1e−30 | 29 | ISKETVELHWGKHHQTYVDGLNKALGTSD |

| 10. | 2.2e−29 | 29 | IEKDFGSFDELVKEFLAEAATLLGSGWVW |

| 11. | 1.0e−311 | 100 | TSFEKDATGKVTAVILKDGKRLRADMVVVGIGIRANTSLFEGQLVVSMVNDGIKVNGQMQTSESSVYAVGDVAAFPIKLFDGDVRRLEHVDSARRTARHA |

| 12. | 4.7e−280 | 100 | ITKSNDGLLSLKTSKETIGGFSHVMFATGRKPNTKNLGLEEAGVEMDKNGAIVVDEYSRTSVESIWAVGDVTNRINLTPVALMEGGAFVKTVFGNEPTKP |

| 13. | 4.1e−144 | 100 | CSSASLALHSFRDSRWLGFRLALPKRGVAGASVPSRHPFLSPVLVAFGKQTRREKCSMFHCASDVNMVTEDDMVDADGTEDEMDPDAAGNPDDGTEGAFP |

| 14 | 1.9e−22 | 21 | EWPKRGGANGSLRFDIELKHG |

| 15. | 4.4e−17 | 15 | KYVILGGGVAAGYAA |

| 16. | 2.1e−63 | 67 | PPPSNDPKPQALPTPLPVLEEVLKAHGPDKNGQAPQPEPFVLAPKLYGKRELLDHFKGWKRPENLGF |

| 17. | 2.5e−142 | 100 | TCVLRGCVPKKLLVYGSKYSHEFEESRGFGWTYETDPKHDWSTLIANKNTELQRLVGIYKNIINNAGVTLIEGRGKIVDPHTVSVNGKLYTAKNILIAVG |

| 18. | 7.8e−102 | 80 | YDYLPYFYSRVFEYEGSSRKVWWQFYGDNVGETVEVGNFDPKIATFWIDSDSRLKGVFLESGISEEFGLLPQLAKSQPIV |

| 19. | 1.3e−100 | 80 | MAAHATLPFSCSSKLQTLTRTLSPRGPLHLRRGFIRLPSLAAFPRFSRAPHPSCRHISASAEASNGASAEGEYDFDLFTI |

| 20. | 1.7e−72 | 57 | WEMVESRLTKAVVRAVERDGPITRRQLRKQLLDRVKDQSRGRPRQGRTLMRRQGNQE |

| 21. | 1.2e−27 | 29 | KAVAVLGANSEVEGVIHFTQEPDGPTTVT |

| 22. | 1.1e−21 | 21 | MAAEVFLKAAAAPPAALGDCP |

| 23. | 1.4e−37 | 41 | DGGWIVDADVIIQGIGEKPPVPPFEAPPENAQVGGKEFDSF |

| 24. | 2.3e−31 | 29 | GGSPDKPLRGLLFFNQEFGVRGLAFLTGD |

| 25. | 5.8e−38 | 29 | IDHLVSWHTVTLRMMRAESFVNLGEPTIP |

| 26. | 7.9e−14 | 11 | DKEGLLQLPSD |

| 27. | 1.0e−36 | 29 | NYPSVSAEYQETVEKARRKLRALIAEKSC |

| 28. | 1.5e−29 | 29 | KIGGNLPGIHYJRDIADADKLVAAJGKKK |

| 29. | 2.6e−21 | 15 | WKVMNWKYAGEVYEN |

| 30. | 1.2e−20 | 15 | WEGMSLGQMMLSSFN |

| 31. | 6.9e−14 | 11 | AHLKLSELGFA |

| 32. | 1.9e−37 | 29 | HAYVKALFSRESFEKTKAAKEHVIAGWAP |

| 33. | 6.8e−27 | 21 | SYKGSKLPYVNSKSPNPPDNY |

| 34. | 2.6e−11 | 11 | KGYLFPENPAR |

| 35. | 2.3e−51 | 41 | DGDKEEEAEPTPEPAAAVPPPPPTPKPAAAAPPPTQKPEPV |

| 36. | 2.2e−13 | 11 | LPYDFDALEPY |

| 37. | 1.4e−50 | 41 | SYSLSPAAWALRQGGGGAARVVRLPSRRRFSVAAAGGGYDN |

| 38. | 1.7e−12 | 9 | MAVPHLIRR |

| 39. | 9.8e−15 | 11 | FNGLKSDVHVF |

| 40. | 7.6e−10 | 8 | AQLKGARE |

| 41. | 3.5e−35 | 29 | SSSVRPFHSLRLVAGSGGAAAARALVVAD |

| 42. | 1.1e−10 | 10 | IATGAEALKL |

| 43. | 5.5e−10 | 7 | VRCMAAS |

| 44. | 1.2e−5 | 11 | YGHTLEELIKE |

| 45. | 1.9e−14 | 11 | FRTSVPGIFAI |

| 46. | 1.9e−22 | 18 | MASGAVVGAGGGLTLCVS |

| 47. | 2.0e−11 | 8 | PPHGKLGW |

| 48. | 3.2e−14 | 11 | VESKDEVVTKQ |

| 49. | 1.5e−9 | 6 | SCWARC |

| 50. | 1.0e−8 | 6 | MASEKH |

Table 4.

Predicted domains and their description in both genotypes (GP-1 and GP-45)

| Gene | Domain description | Accession | Super family | No. of predicted domains in GP-45 | No. of predicted domains in GP-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EcDHAR | Glutathione dehydrogenase (ascorbate) | cl25455 | PLN02817 | 1 | 1 |

| EcGR | Glutathione reductase | PLN02546 | cl27343 | 1 | 1 |

| EcAPX | Plant peroxidase like superfamily | – | cl00196 | 1 | 1 |

| Ascorbate peroxidase | cd00691 | cd00691 | 3 | 3 | |

| EcSOD | PLN02386 | PLN02386 | cl00891 | 1 | 1 |

| Sod Fe C superfamily | – | – | 3 | 3 | |

| Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase superfamily | cl27368 | – | 2 | 2 | |

| EcMDHAR | Pyr redox 2 | Pfam07992 | cl26177 | 3 | 3 |

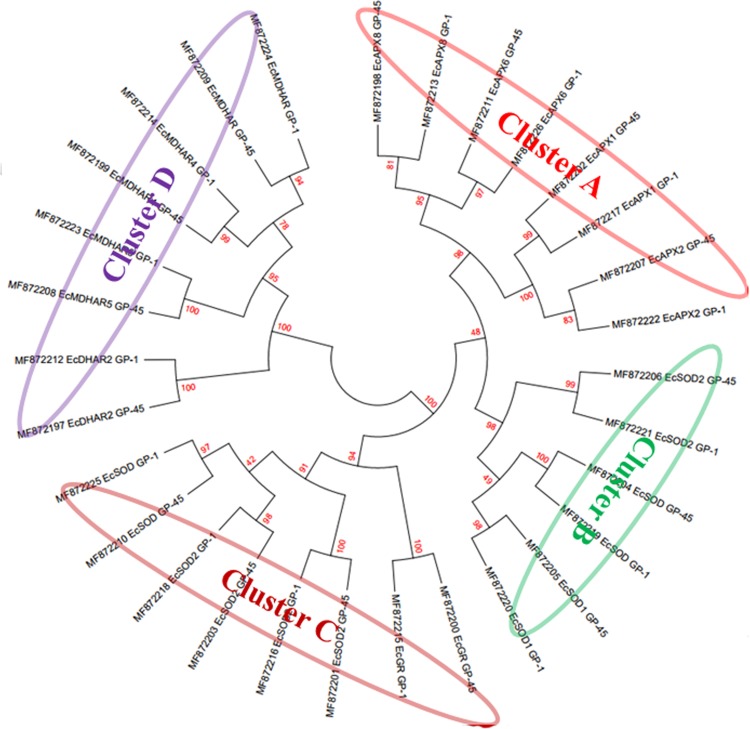

Comparative phylogenetic analysis

To examine the evolutionary relationships among the ROS family proteins in E. coracana, phylogenetic analysis was performed. To infer diverse conserved cluster, a rooted tree was constructed from alignments of the full-length protein sequences using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method. The tree revealed four main phylogenetic clusters from A to D, based upon the bootstrap values. Cluster A and B contained APX and Sod genes, whereas cluster C contained the sequences of GR genes which are closely related with Sod genes and cluster D holds MDHAR and DHAR genes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of ROS-producing genes of two finger millet genotypes (GP-1 and GP-45). Neighbor-joining tree was generated using MEGA7 software with 1000 bootstrap value. The tree correctly classifies the genes in alternate manner of GP-1 and GP-45, showing four different clusters namely cluster A (red color), cluster B (green color), cluster C (burgundy color), and cluster D (violet color)

Gene ontology and enrichment analysis

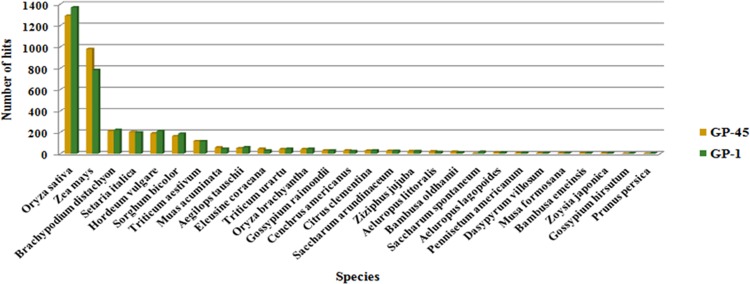

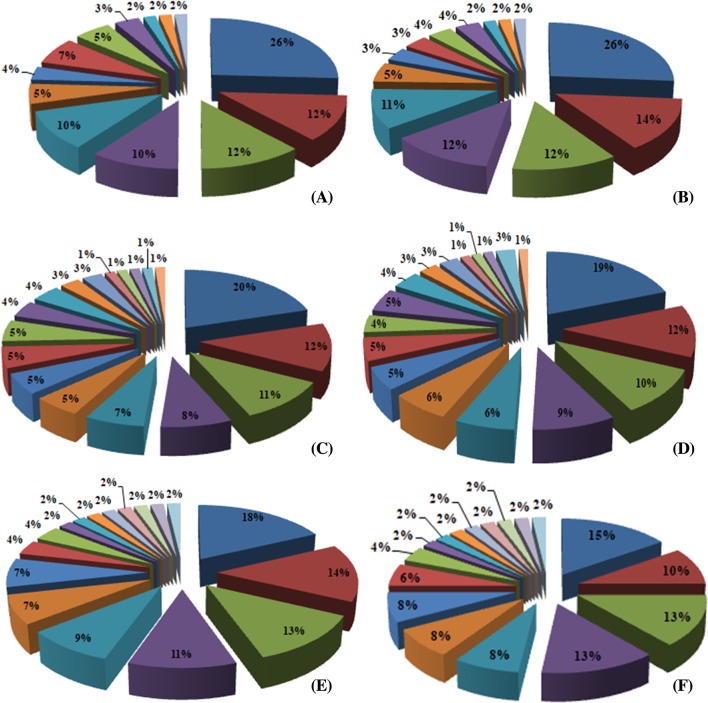

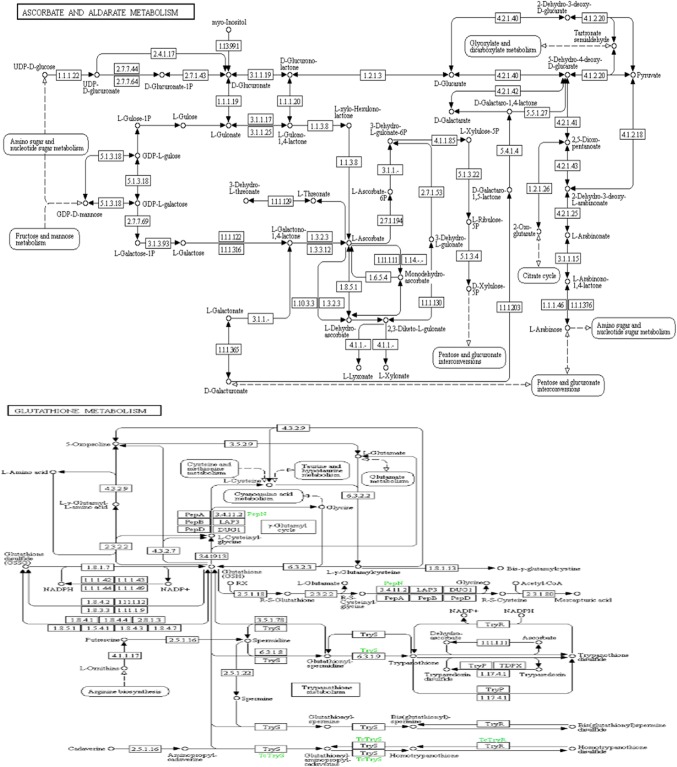

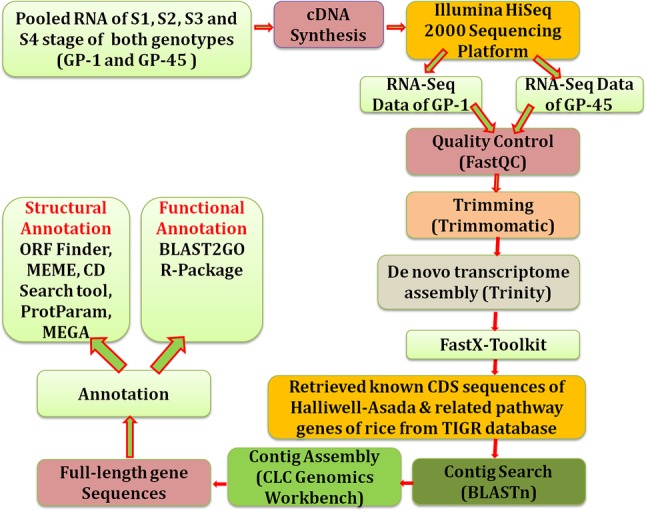

To verify the function of identified genes in different biological processes and molecular function as well as other roles during developmental stage of spikes, gene ontology (GO) and enrichment analysis was performed. For GO term enrichment analysis, three methods (Blast2GO, AgriGO, and GeneCoDis) were used, which yielded similar results with slight variation in the number of GO terms and the order of significance. Results obtained from Blast2GO, AgriGO, and GeneCoDis are presented in Table 5. Mostly ROS-producing input sequences hit with the sequences of Oryza sativa and Zea mays species (Fig. 4). The majority was assigned to molecular function [18 (38.29%)], followed by cellular component [16 (34.04%)] and biological process [13 (27.65%)] was the least. Consistent with the previous known functions of EcROS, GO terms related to oxidation–reduction process and cellular oxidant detoxification were among the enriched terms of biological process and oxidoreductase activity and metal ion binding were enriched terms of molecular function, respectively. In addition, GO terms “response to oxidative stress” are also highly enriched (Fig. 5a, b). A significant enrichment of GO terms associated with abiotic factors such as “response to heat” and “response to high light intensity” was observed in some genes. In cellular component ontology, the maximum number of genes were associated with membrane (GO:0016020), plastid (GO:0009536), cytoplasm (GO:0005737), and cell (GO:0005623). ROS are also produced at several other localizations such as in integral component of membrane (GO:0016021), mitochondrion (GO:0005739), chloroplast stroma (GO:0009570), peroxisome (GO:0005777), nucleoid (GO:0009295), thylakoid (GO:0009579), and mitochondrial matrix (GO:0005759) of cell. BLAST2GO analysis also revealed the involvement of Halliwell–Asada pathway (APX, DHAR, MDHAR, and GR) genes in the other pathways, viz., glutathione metabolism (KEGG:00480) and ascorbate–aldarate metabolism (KEGG:00053). These pathways are indirectly connected to the polyphenolic biosynthetic pathways (Fig. 6).

Table 5.

Enriched GO terms in categories of biological process, molecular function, and cellular component

| GO category | GO accession | GO terms | No. of GP-1 genes involved in subcategory | No. of GP-45 genes involved in subcategory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological process | GO:0055114 | Oxidation–reduction process | 15 | 15 |

| GO:0098869 | Cellular oxidant detoxification | 7 | 8 | |

| GO:0006801 | Superoxide metabolic process | 7 | 7 | |

| GO:0019430 | Removal of superoxide radicals | 6 | 7 | |

| GO:0006979 | Response to oxidative stress | 6 | 6 | |

| GO:0045454 | Cell redox homeostasis | 3 | 3 | |

| GO:0006749 | Glutathione metabolic process | 2 | 2 | |

| GO:0022900 | Electron transport chain | 4 | 2 | |

| GO:0042744 | Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | 3 | 2 | |

| GO:0006351 | Transcription, DNA-templated | 2 | 2 | |

| GO:0071486 | Cellular response to high light intensity | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0034599 | Cellular response to oxidative stress | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0006355 | Regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 1 | 1 | |

| Molecular function | GO:0016491 | Oxidoreductase activity | 15 | 15 |

| GO:0046872 | Metal ion binding | 9 | 9 | |

| GO:0004601 | Peroxidase activity | 8 | 8 | |

| GO:0004784 | Superoxide dismutase activity | 6 | 7 | |

| GO:0050660 | Flavin adenine dinucleotide binding | 5 | 5 | |

| GO:0005507 | Copper ion binding | 4 | 5 | |

| GO:0020037 | Heme binding | 4 | 4 | |

| GO:0016688 | L-ascorbate peroxidase activity | 4 | 4 | |

| GO:0008270 | Zinc ion binding | 3 | 4 | |

| GO:0015036 | Disulfide oxidoreductase activity | 4 | 3 | |

| GO:0016656 | Monodehydroascorbate reductase (NADH) activity | 3 | 3 | |

| GO:0016209 | Antioxidant activity | 1 | 2 | |

| GO:0005524 | ATP binding | 2 | 2 | |

| GO:0016740 | Transferase activity | 2 | 2 | |

| GO:0045174 | Glutathione dehydrogenase (ascorbate) activity | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0004364 | Glutathione transferase activity | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0003700 | Transcription factor activity, sequence-specific DNA binding | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0003677 | DNA binding | 1 | 1 | |

| cellular component | GO:0016020 | Membrane | 10 | 8 |

| GO:0009536 | Plastid | 7 | 7 | |

| GO:0005737 | Cytoplasm | 6 | 7 | |

| GO:0005623 | Cell | 8 | 5 | |

| GO:0016021 | Integral component of membrane | 4 | 4 | |

| GO:0005739 | Mitochondrion | 4 | 4 | |

| GO:0009570 | Chloroplast stroma | 5 | 4 | |

| GO:0009295 | Nucleoid | 2 | 3 | |

| GO:0009579 | Thylakoid | 2 | 2 | |

| GO:0005759 | Mitochondrial matrix | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0005777 | Peroxisome | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0005773 | Vacuole | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0042644 | Chloroplast nucleoid | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0042646 | Plastid nucleoid | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0010319 | Stromule | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0048046 | Apoplast | 1 | 1 | |

| GO:0005634 | Nucleus | 1 | 1 |

Fig. 4.

Distribution of blast top-hits species. Graph depicting the major hit species, i.e., Oryza sativa and Zea mays

Fig. 5.

a Gene ontology distribution and functional classification of ROS-producing genes in GP-1 and GP-45 genotypes. Tortadiagram comparatively represented the percentage of GP-1 (left) and GP-45 (right) genes for three categories, viz., a, b Biological process, c, d molecular function and cellular component (e, f). b List of gene ontology categories. a Biological processes, b molecular functions, and c cellular components

Fig. 6.

Blast2GO generated KEGG pathway of ascorbate and aldarate metabolism (KEGG:00053) and Glutathione metabolism (KEGG:00480), showing involvement of ascorbate peroxidase (1.11.1.11), monodehydroascorbate reductase (1.6.5.4), glutathione reductase (1.8.1.7), and dehydroascorbate reductase (1.8.5.1) enzymes in both pathway

Differential gene expression analysis and estimation of transcript abundance

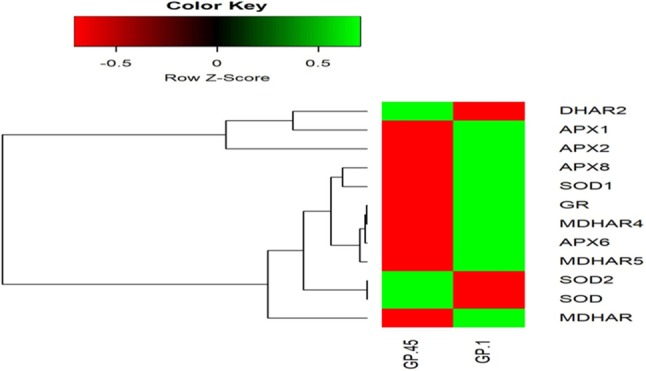

In the present study, expression of ROS-producing genes APX, MDHAR, DHAR, GR, and SOD, and a total of 24 genes (12 from each genotype) were compared in both GP-1 and GP-45 genotype transcriptome data of finger millet. Furthermore, FPKM values for the unitranscripts were determined using BAM (Binary Alignment Map) file of RNA-Seq data (Supplementary Table 3). These FPKM values were plotted in the form of heat map for each identified ROS-producing genes (Fig. 7). The heat map showed that the MDHAR and SOD genes were low expressed, as the FPKM value is 0 in pooled spike sample of GP-45 and GP-1 genotype, respectively, whereas DHAR gene is highly expressed in GP-45 and APX2 in GP-1. APX2 respond two times higher expression in GP-1, while other genes are normally expressed.

Fig. 7.

Heat map of 24 ROS-producing genes in GP-1 and GP-45 genotypes. Heat map representing clusters of differentially expressed 24 ROS-producing genes. Highly expressed genes are represented in green and low expressed genes are represented in red color. At the top right, color scale represents log transformed FPKM value. FPKM value smaller than 1 was not calculated due to negative logarithm

Discussion

In recent years, globally growing awareness of health has drawn more attention to produce ample amount of natural antioxidants for fast growing population. Besides, from the past few years, antioxidants play an important role in cosmetics, beverages, and food industries (Lobo et al. 2010). Natural antioxidants are safe for human health and do not have any side effects. Various studies suggest that the higher consumption of antioxidants can slow down the aging process and minimize the risk of cancer, diabetes, and neurological disorders (Rahman 2007). Millets belong to the family Poaceae, which have been used by man as food crop. However, finger millet crop has received enormous importance due to its antioxidant and nutritional properties. Out of the 13 major/minor millet species, finger millet is widely cultivated as a source of high-valued seed calcium, antioxidants, dietary fibers, and other micronutrients (Devi et al. 2014).

In the present study, computational and RNA-Seq approaches have been used to identify genes involved in AsA–GSH cycle and related pathway in E. coracana to understand metabolic and transcriptional regulatory networks during antioxidants synthesis. A total of 120,130 and 109,218 contigs were generated from both genotypes, and nearly quarter of them annotated against the non-redundant database of NCBI. To our knowledge, this is one of the first reports of transcriptome analysis of AsA–GSH cycle or Halliwell–Asada pathway genes in finger millet.

The sequence analysis of ROS-producing genes at protein level revealed their physicochemical properties included amino acid composition, aliphatic index, instability index, molecular weight, theoretical pI, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) were found in apposite range for influencing the stability of protein (Gasteiger et al. 2005). The properties of DHAR2, SOD2, APX1, and APX2 were found identical; based on physicochemical properties, these genes might be play similar function in both genotypes.

To dissect the complexity among ROS-producing genes, sequences were imported to MEME for motif analysis which discovers novel recurring un-gapped motifs of fixed or variable length (Bailey et al. 2009). The main objective of motif identification is to find the structural similarities and molecular variations among genes, and then, domain analysis was performed to confirm the architecture of ROS-producing genes using the CD Search tool which detects structural as well as functional domains found in protein sequences (Derbyshire et al. 2015). A total of 30 sequences were analyzed along with partial- and full-length sequences to investigate the functional role on the basis of their conserved domain; a total of 8 different types of domains were found in ROS-producing proteins. The positions of domains are varying in both genotypes; but the amino acid residues of domains are found identical. Therefore, it is concluded that the genes of both genotype may perform similar function. In plants, SOD gene family comprises of Cu–Zn and Fe–C superoxide domain. The DHAR and GR gene family comprises of only a single glutathione domain, but this glutathione is differ in both family showing dehydrogenase and reductase properties. On the basis of glutathione domain, these two gene family shares evolutionary relationship and showing close relatedness in phylogenetic tree. Variations in number of domain were also recorded, but no such difference was found in both genotypes.

Furthermore, comparative phylogenetic analysis was carried out to classify the ROS-producing gene families. The phylogenetic tree correctly classified and perfectly matched the genes of both genotypes with alternate manner of GP-1 and GP-45 genes. In addition, to identify the role of these genes in category of biological process, molecular function, and cellular component, gene ontology and enrichment analysis was performed using Blast2GO (Conesa and Gotz 2008). The terms “oxidation–reduction process” and “cellular oxidant detoxification” were enriched in biological process category, and the terms “oxidoreductase activity” and “membrane” were enriched in molecular function and cellular component category. These enzymes were found enriched in the other localizations viz. mitochondrion (GO:0005739), chloroplast stroma (GO:0009570), peroxisome (GO:0005777). Sharma et al. (2012) also reported the different sub-cellular locations of AsA–GSH cycle genes. To better understand the genetic interaction and involvement of other biological pathways in antioxidants synthesis, all unigenes were searched against the cross-referenced KEGG pathway database. BLAST2GO analysis revealed that the genes of Halliwell–Asada pathway (APX, DHAR, MDHAR, and GR) are also a part of two other pathways, viz., glutathione metabolism (KEGG:00480) and ascorbate–aldarate metabolism (KEGG:00053). These pathways are indirectly connected to the biosynthetic pathways of polyphenolic compounds (flavonoid, tannin, and lignin) that have a significant antioxidant potential (Sharma et al. 2012). To identify the role of ROS-producing genes in antioxidants synthesis, the expression level of these genes was also compared by calculating the FPKM values of 24 genes using developing spikes transcriptome data of both genotypes. FPKM is a quantification method for the detection of gene expression which is obtained from RNA-Seq data. It depends upon the number of sequencing reads and total read length. The results of expression analysis revealed that the expression of APX gene was higher in both the genotypes followed by DHAR and GR. MDHAR gene of GP-1 and SOD gene of GP-45 were found less expressed which shown the major alternations in both genotype. The FPKM values of these genes are found 0 due to their low expression.

Conclusion

The present computational study represents a comprehensive RNA-Seq approach in the non-model organism finger millet to generate functional genomics resources for modern nutrition biology research to deciphering its antioxidants potential for bio-fortification of the other staple food crops. We have concluded that all ROS-producing genes are involved in oxidation–reduction processes and showed good oxidoreductase activity as compared to metal ion binding, ATP binding, and DNA binding, and other biological activities. APX2 of GP-45 was found excellent in the expression analysis that showed two times higher expression as compared to APX1, APX6, and APX8 in both genotype, whereas MDHAR and SOD genes were low expressed in high- and low-seed Ca+ 2 genotypes, respectively. Therefore, it is concluded that MDHAR and SOD genes might be modulated antioxidant activities and stress tolerance ability in finger millet. Comparatively, the FPKM values of genes were found in GP-1 are higher in comparison to GP-45. Thus, GP-1 genotype has more antioxidant activities and stress tolerance ability in comparison to GP-45. Our finding suggests that the GP-1 genotype is superior, able to reduce the risk of abiotic stresses, helpful to detoxifying the harmful agents (metabolic end products, micro-organisms, contaminants, pollutants, insecticides, pesticides, food additives, drugs, and alcohol) from the body and work as antioxidants. Besides, it also holds essential nutrients which are able to minimize the cell damage that may lead to the prevention of various diseases such as heart diseases, cancer, Alzheimer’s, and many more.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Bioinformatics Centre (Sub DIC) at G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, India and Bioinformatics Centre (DIC) at ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa, New Delhi, India for providing research facilities.

Author contributions

PWR and AK conceptualized the idea of manuscript and supervised all the experiments. HA performed all the experiments interpreted the results and formulated the manuscript independently. NP helped in Gene Ontology analysis. RKP and AKM assisted, edited, and updated the manuscript. RKP, SA, AKM, VKG, PWR, and AK contributed critically by revising the draft, provided valuable suggestions, and updating the manuscript for publication.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Himanshu Avashthi, Email: him.awasthi1989@gmail.com.

Pramod Wasudeo Ramteke, Email: pwramteke@yahoo.com.

Anil Kumar, Email: anilkumar.mbge@gmail.com.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony U, Mosses LG, Chandra TS. Inhibition of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli by fermented flour of finger millet (Eleusine coracana) World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;14:883–886. doi: 10.1023/A:1008871412183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avashthi H, Jha R, Sharma M, Yadav AK, Mishra AK, Ramteke PW, Kumar A. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) Approach for classification of seed storage proteins of various nutritionally superior cereal crops. Int J Agricu Sci. 2017;9:3749–3751. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Montagu MV, Inze D. Superoxide dismutase and stress tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:83–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.43.060192.000503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Saez P, Chagoyen M, Tirado F, Carazo JM, Pascual-Montano A. GENECODIS: a web-based tool for finding significant concurrent annotations in gene lists. Genome Biol. 2007;8(1):R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekara A, Shahidi F. Content of insoluble bound phenolics in millets and their contribution to antioxidant capacity. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:6706–6714. doi: 10.1021/jf100868b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekara A, Shahidi F. Antiproliferative potential and DNA scission inhibitory activity of phenolics from whole millet grains. J Funct Foods. 2011;3:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2011.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekara A, Shahidi F. Inhibitory activities of soluble and bound millet seed phenolics on free radicals and reactive oxygen species. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:428–436. doi: 10.1021/jf103896z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chethan S, Malleshi NG. Finger millet polyphenols: characterization and their nutraceutical potential. Am J Food Technol. 2007;2(7):582–592. doi: 10.3923/ajft.2007.582.592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchole M, Pathak RK, Singh UM, Kumar A. Molecular characterization of EcCIPK24 gene of finger millet (Eleusine coracana) for investigating its regulatory role in calcium transport. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(4):267. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0874-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Gotz S. Blast2GO: A comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int J Plant Genomics. 2008;2008:619832. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, He J, Marchler GH, Wang Z, Marchler-Bauer A (2015) Improving the consistency of domain annotation within the Conserved Domain Database. Database (Oxford). 12;2015. pii: bav012. 10.1093/database/bav012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Devi PB, Vijayabharathi R, Sathyabama S, Malleshi NG, Priyadarisini VB. Health benefits of finger millet (Eleusine coracana L.) polyphenols and dietary fiber: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51:1021–1040. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0584-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z. agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W64–W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT (2004) Food and agriculture organization statistical database. http://www.fao.org/docrep/T0818E/T0818E05.htm

- Garg VK, Avashthi H, Tiwari A, Jain PA, Ramkete PW, Kayastha AM, Singh VK. MFPPI -Multi FASTA ProtParam interface. Bioinformation. 2016;12:74–77. doi: 10.6026/97320630012074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: John MW, editor. The proteomics protocols handbook. New York: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Khan NA, Anjum NA, Tuteja N. Amelioration of cadmium stress in crop plants by nutrients management: morphological, physiological and biochemical aspects. In: Anjum NA, Lopez-Lauri F, editors. Plant nutrition and abiotic stress tolerance III, plant stress 5 (Special Issue 1) Ikenobe: Global Science Books Ltd.; 2011. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan C, Sastri R, Subramaniam B. Nutritive values of Indian food. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan C, Ramashastri BV, Balasubramanium SC. Nutritive value of Indian foods. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), Indian Council of Medical Research; 2004. pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Graf E, Eaton JW. Antioxidant functions of phytic acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90146-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Pathak RK, Gupta SM, Gaur VS, Singh NK, Kumar A. Identification and molecular characterization of Dof transcription factor gene family preferentially expressed in developing spikes of Eleusine coracana L. 3 Biotech. 2018;8(2):82. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-1068-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruprasad K, Reddy BV, Pandit MW. Correlation between stability of a protein and its dipeptide composition: a novel approach for predicting in vivo stability of a protein from its primary sequence. Prot Eng. 1990;4:155–164. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Reactive species and antioxidants. Redox biology is a fundamental theme of aerobic life. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:312–322. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.077073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignacimuthu S, Ceasar SA. Development of transgenic finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.) resistant to leaf blast disease. J Biosci. 2012;37:135–147. doi: 10.1007/s12038-011-9178-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikai AJ. Thermostability and aliphatic index of globular proteins. J Biochem. 1980;88:1895–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Antioxidants in fruits and vegetables-The millennium’s health. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2001;36:703–725. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2001.00513.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kokane SB, Pathak RK, Singh M, Kumar A. The role of tripartite interaction of calcium sensors and transporters in the accumulation of calcium in finger millet grain. Biologia Plantarum. 2018;62(2):325–334. doi: 10.1007/s10535-018-0776-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Mirza N, Charan T, Sharma N, Gaur VS. Isolation, characterization and immunolocalization of a seed dominant Cam from finger millet (Eleusine coracana L. Gartn.) for studying its functional role in differential accumulation of calcium in developing grains. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:2955–2973. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Gaur VS, Goel A, Gupta AK (2015a) De Novo Assembly and Characterization of Developing Spikes Transcriptome of Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana): a Minor Crop Having Nutraceutical Properties. 33:905–922

- Kumar A, Pathak RK, Gupta SM, Gaur VS, Pandey D. Systems biology for smart crops and agricultural innovation: filling the gaps between genotype and phenotype for complex traits linked with robust agricultural productivity and sustainability. Omics: J Integr Biol. 2015;19:581–601. doi: 10.1089/omi.2015.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Metwal M, Kaur S, Gupta AK, Puranik S, Singh S, Singh M, Gupta S, Babu BK, Sood S, Yadav R. Nutraceutical value of finger millet [Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.], and their improvement using omics approaches. Front Plant Science. 2016;7:934. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari L, Sumathi S. Effect of consumption of finger millet on hyperglycemia in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) subjects. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2002;57:205–213. doi: 10.1023/A:1021805028738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:118–126. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari R, Dubey RS. Nickel-induced oxidative stress and the role of antioxidant defense in rice seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2009;59:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s10725-009-9386-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meriga B, Reddy BK, Rao KR, Reddy LA, Kishor PBK. Aluminium-induced production of oxygen radicals, lipid peroxidation and DNA damage in seedlings of rice (Oryza sativa) J Plant Physiol. 2004;161:63–68. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:453–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Jha AB, Dubey RS. Arsenite treatment induces oxidative stress, upregulates antioxidant system, and causes phytochelatin synthesis in rice seedlings. Protoplasma. 2011;248:565–577. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath M, Goel A, Taj G, Kumar A. Molecular cloning and comparative in silico analysis of calmodulin genes from cereals and millets for understanding the mechanism of differential calcium accumulation. J Proteom Bioinforma. 2010;3:294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Foyer CH. Ascorbate and glutathione: keeping active oxygen under control. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 1998;49:249–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obilana AB, Manyasa E. “Millets”. In: Belton PS, Taylor JRN, editors. Pseudocereals and Less Common Cereals. Grain Properties and Utilization Potential. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2002. pp. 176–217. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar P, Nath M, Yadav VK, Kumar A. Comparative evaluation of genetic diversity using RAPD, SSR and cytochome P450 gene based markers with respect to calcium content in finger millet (Eleusine coracana L. Gaertn.) J Genet. 2010;89:121–133. doi: 10.1007/s12041-010-0052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak RK, Baunthiyal M, Shukla R, Pandey D, Taj G, Kumar A. In silico identification of mimicking molecules as defense inducers triggering jasmonic acid mediated immunity against Alternaria blight disease in Brassica species. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:609. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman K. Studies on free radicals, antioxidants, and co-factors. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:218–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran NS, Nithya M, Rose C, Chandra TS. The effect of finger millet feeding on the early responses during the process of wound healing in diabetic rats. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2004;1689:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalbert A, Manach C, Morand C, Remesy C. Dietary polyphenols and prevention of diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2005;45:287–306. doi: 10.1080/1040869059096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seetharam A, Riley KW, Harinarayana G (1986) Small millets in global agriculture. In: Proceedings of the First International Small Millets Workshop, Oct 29–Nov 2, 1986, Bangalore, India, 21–23

- Shah K, Kumar RG, Verma S, Dubey RS. Effect of cadmium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide anion generation and activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice seedlings. Plant Sci. 2001;161:1135–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00517-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi F, Chandrasekara A. Millet grain phenolics and their role in disease risk reduction and health promotion: a review. J Funct Foods. 2013;5:570–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Dubey RS. Drought induces oxidative stress and enhances the activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2005;46:209–221. doi: 10.1007/s10725-005-0002-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J Bot. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/217037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh UM, Chandra M, Shankhdhar SC, Kumar A. Transcriptome wide identification and validation of calcium sensor gene family in the developing spikes of finger millet genotypes for elucidating its role in grain calcium accumulation. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripriya G, Chandrasekharan K, Murty VS, Chandra TS. ESR spectroscopic studies on free radical quenching action of finger millet (Eleusine coracana) Food Chem. 1996;57:537–540. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(96)00187-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Dubey RS. Manganese-excess induces oxidative stress, lowers the pool of antioxidants and elevates activities of key antioxidative enzymes in rice seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2011;64:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10725-010-9526-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A, Avashthi H, Jha R, Srivastava A, Garg VK, Ramteke PW, Kumar A. Insights using the molecular model of Lipoxygenase from Finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.)) Bioinformation. 2016;12:156–164. doi: 10.6026/97320630012156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenols. Nutrients. 2010;2:1231–1246. doi: 10.3390/nu2121231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Dubey RS. Lead toxicity induces lipid peroxidation and alters the activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice plants. Plant Sci. 2003;164:645–655. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00022-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wan X, Zheng Y, Sun L, Chen Q, Zhu X, Guo Y, Liu M. Effects of nitrogen on the activity of antioxidant enzymes and gene expression in leaves of Populus plants subjected to cadmium stress. J Plant Interact. 2013;9:599–609. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2013.879676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Qiong-Yi, Wang Yi, Kong Yi-Meng, Luo Da, Li Xuan, Hao Pei. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl 14):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S14-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.