Abstract

Patients with chronic renal failure are more susceptible to infections due to acquired immunodeficiency caused by uremia. Parasitic infections are one of the significant causes of morbidity and mortality in those patients, So we aimed to assess the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. and other protozoan infections in patients undergoing hemodialysis in Qena Governorate, Upper Egypt. The present study took place in Qena University Hospitals, Egypt. Participants were 150 Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) patients undergoing hemodialysis, and 50 healthy individuals. After questionnaire, three consecutive stool samples from each participant were examined macroscopically and microscopically by different techniques for the presence of different stages of different protozoa. 66% of CKD patients and 26% of the control group were infected with intestinal protozoa. Cryptosporidium spp. were the protozoa with the highest prevalence in cases (40%) and control (6%) with statistical significance (P < 0.05). It was detected only in watery stool samples (P value < 0.05). Residence, age and gender were not significant variables in the prevalence of infection among patients with CKD. In Egypt, few studies had reported the prevalence of Cryptosporidiosis in chronic renal patients. Cryptosporidium infection should be suspected in all cases of prolonged watery diarrhea in CKD patients and stool samples should be examined using special stains as cold modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining for proper diagnosis of Cryptosporidium infections.

Keywords: Cryptosporidium, Hemodialysis, Egypt

Introduction

Chronic renal failure (CRF) is a gradual and irreversible loss of the kidney functions with retention of a large number of compounds (uremic toxins) that are normally excreted in urine (Glorieux et al. 2013). Accumulation of uremic toxins in the body leads to defective functions of the immune system due to impairment of leukocyte function (as defective phagocytosis and migration) and antibody production (Chonchol 2006; Ocak and Eskiocak 2008). Defects in the immune system are associated with high susceptibility to different viral and parasitic infections which are the second most significant factor responsible for morbidity and mortality in chronic renal failure patients after cardiovascular diseases (Tonelli et al. 2006).

Intestinal parasites (IPs) especially opportunistic ones as Cryptosporidium spp. have a high prevalence rates in developing countries—including Egypt—especially in immunocompromised patients as chronic kidney disease patients undergoing hemodialysis (Karadag et al. 2013). Cryptosporidium is a coccidian protozoan parasite infect humans and animals via the fecal–oral route, it causes gastrointestinal manifestations in the form of watery or mucoid diarrhea with abdominal pain that may persist from a few days to much longer (Hunter and Nichols 2002; Mohaghegh et al. 2015). In immunocompetent individuals, cryptosporidiosis is benign and self-limiting, however it is a major cause of acute and persistent diarrhea with significant morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. (Mohammadi-Manesh et al. 2014; Mohaghegh et al. 2015). In 1982, Cryptosporidium was listed as a serious protozoan infection in immunosuppressed patients when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 14 deaths among 21 AIDS cases with fulminant diarrhea caused by this protozoan infection (CDC 1982; Ungar 2000). In recent years, Cryptosporidium infection in immunosuppressed non-AIDS patients—including renal failure patients—has been given attention. Unfortunately, few studies had been conducted to assess the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in renal patients worldwide (Hunter and Nichols 2002; Azami 2007; Azami and Hejazi 2010; Mohammadi-Manesh et al. 2014; Mohaghegh et al. 2015).

In Egypt, few studies had reported the prevalence of Cryptosporidiosis in chronic renal patients which ranged from 6 to 28.8% (Abaza et al. 1995; Ali et al. 2000; Baiomy et al. 2010).

The present study aimed to assess the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. and other protozoan infections in patients undergoing hemodialysis in Qena Governorate, Upper Egypt.

Materials and methods

Study population and sample collection

The present study is a case control study. It was conducted in Qena university Hospitals, Egypt, in the period from June to December 2017. Participants were 150 patients suffering from Chronic Kidney Disease and treated with hemodialysis (with variables durations from the onset of hemodialysis (3–10 years), and a control group of 50 healthy individuals. Age of patients in the CKD group ranged from 38 to 73 years. 93 patients were males, 69 were from urban areas. Diabetes and hypertension were the common associating diseases. On the other hand, the control group consisted of 23 males and 27 females, age of participants ranged from 20 to 66 years old. 27 individuals were from urban areas.

Each participant was asked to collect stool samples in clean tight fitting containers labeled with the patient’s name and date of collection of the sample. Three consecutive samples were examined for each case.

Stool examination

The fecal samples were examined macroscopically to determine the consistency, presence of blood or mucus and presence of parasites (Garcia 2001). Microscopic examination of all samples was done by different techniques for detection of different stages of parasites. First of all, direct smears were done, where mixtures of stool with one drop of 0.85% Nacl or with one drop of iodine were prepared and examined microscopically (Ash and Orihel 1984). Different concentration techniques as simple sedimentation, floatation sedimentation and formol ether Sedimentation were used for recovery of different parasites (Ma and Soave 1983; Melvin and Brooke 1982; Ash and Orihel 1984; Garcia 2001). Then samples were stained by cold modified acid fast stains according to (Mehta 2002) for detection of cryptosporidium.

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of Qena Faculty of Medicine, South Valley University, Qena, Egypt. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis were performed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 16. Chi square test was used to assess the significance of association of intestinal protozoan parasites with the independent variables. Fischer exact test was used when number of cells is less than 5. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The present study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of intestinal protozoan infections in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients on hemodialysis with special concern to Cryptosporidium spp. in comparison with a control group of healthy individuals. So, a case control study was designed and included 150 patients with CKD and 50 healthy individuals. In the CKD group, age of patients ranged from 38 to 73 years (mean: 56.98 ± 7.23). 62% of patients were males, 42% were from urban areas. 20% were diabetic, 42% were hypertensive and 36% were both diabetic and hypertensive. On the other hand, in the control group, age ranged from 20 to 66 years (mean: 48.4 ± 12.6). 46% were males, 54% were from urban areas.

Macroscopic examination of stool samples showed marked variation in the consistency of stool among cases and control ranging from formed (20% of cases only), semi-formed (30% of cases and 66% of control) and watery stool (50% of cases and 34% of control), with variable duration of diarrhea (2–7 days) and a wide range of motions per day (3–7) day.

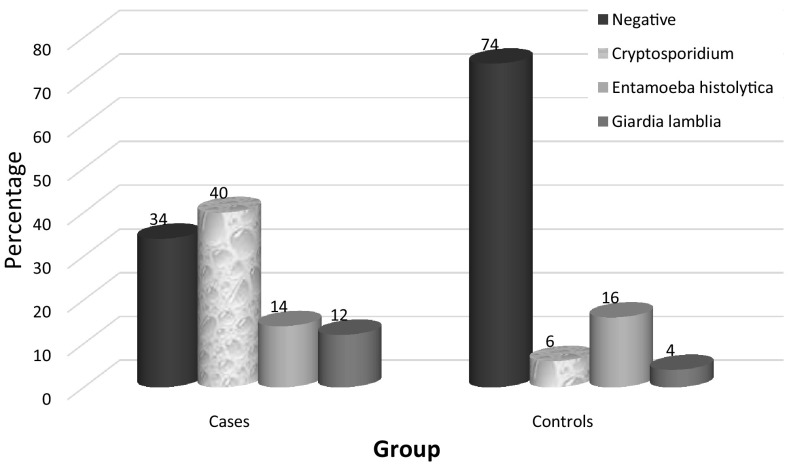

Microscopic examination of stool samples revealed the presence of different protozoan parasites. 66% (99/150) of CKD patients and 26% (13/50) of the control group were infected with intestinal protozoa with statistical significance (P < 0.05). Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of intestinal protozoa among CKD patients and control groups

| Group | Total | Negative no. (%) | Cryptosporidium spp. no. (%) | Entamoeba histolytica no. (%) | Giardia lamblia no. (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 150 | 51 (34.00) | 60 (40.00) | 21 (14.00) | 18 (12.00) | < 0.0001 |

| Controls | 50 | 37 (74.00) | 3 (6.00) | 8 (16.00) | 2 (4.00) |

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of intestinal protozoa among CKD patients and control groups

The majority of CKD patients positive for intestinal protozoa were males (42%) from urban areas, on the contrary to the control group where most of individuals positive for intestinal protozoa were females (25.93%) from urban areas with no statistical significance (P > 0.05). The protozoan parasites recovered from stool examination were in the form of Cryptosporidium parvum (40%) and (6%), Entameba histolytica infection (14%) and (16%), Giadria lamblia (12%) and (4%) in CKD and control groups respectively. Difference in the prevalence of these protozoa between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Cryptosporidium spp. were the protozoa with the highest prevalence in both CKD and control group (40%) and (6%), respectively. It was detected only in watery stool samples (P value < 0.05). Infection was variable among age groups with the higher prevalence in patients < 40 years in both CKD and control groups with no statistical significance (P value < 0.05). Residence was not a significant variable in the prevalence of infection among patients with CKD where Cryptosporidium spp. were detected in 47.8% in patients from rural areas and in 33.3% in patients from urban areas. In the control group, Cryptosporidium spp. were detected in 8.70% (2/23) from rural areas and in 3.70% (1/27) from urban areas. Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Showing the clinical data of patients and control group infected with Cryptosporidium spp

| Cases | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Infected | P value | Total | Infected | P value | |

| No (%) | No (%) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 93 | 39 (41.9) | 0.97 | 23 | 1 (2) | 0.88 |

| Females | 57 | 21 (36.8) | 27 | 2 (4) | ||

| Age groups | ||||||

| < 40 | 3 | 3 (100) | 0.99 | 13 | 8 (61.54) | 0.76 |

| 40 to ≤ 50 | 21 | 9 (42.86) | 17 | 12 (70.59) | ||

| 50 to ≤ 60 | 72 | 30 (41.67) | 17 | 14 (82.35) | ||

| > 60 | 54 | 18 (33.33) | 3 | 3 (100) | ||

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 81 | 33 (40.74) | 0.75 | 23 | 2 (8.7) | 0.86 |

| Urban | 69 | 27 (39.13) | 27 | 1 (3.7) | ||

| Contact with domesticated animals | ||||||

| Yes | 87 | 36 (41.3) | 0.032 | 23 | 3 (100) | 0.032 |

| No | 63 | 24 (38.1) | 27 | 0 (0) | ||

| Consistency of stool | ||||||

| Formed | 30 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.000 | 2 (4) | 0.002 | |

| Semi-formed | 45 (30) | 0 (0) | 33 (66) | |||

| Watery | 75 (50) | 60 (80) | 15 (30) | |||

| Duration of dialysis | ||||||

| < 5 years | 60 | 15 | 0.995 | |||

| > 5 years | 90 | 45 | ||||

| Total | 150 | 60 | 50 | 3 | ||

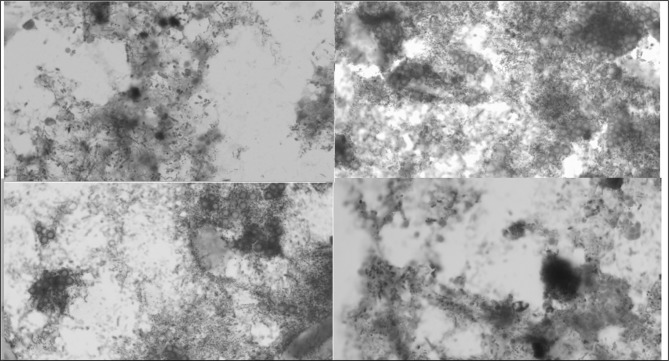

Fig. 2.

Stool samples stained by Ziehl–Neelsen stains showing oocysts of Cryptosporidium spp. Magnification power 1000 ×

Discussion

Patients with chronic renal failure who are on hemodialysis are more susceptible to opportunistic viral, bacterial and parasitic infections, as a result dysfunction of their immune response (Chonchol 2006). The present study was designed to find out the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp and other intestinal protozoa among patients suffering from chronic renal failure and undergoing hemodialysis. So, stool samples were collected from 150 patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis and 50 healthy controls. Examination of these samples showed high prevalence of intestinal protozoal infections among hemodialysis patients (66%) compared to (26%) in the healthy control group. Higher results were reported by El Nadi and Taha who reported 94% prevalence rate of intestinal parasitic infections (both helminthes and protozoa) in hemodialysis patients in Sohag governorate, Egypt (El-Nadi and Taha 2004).

On the other hand, Abaza et al. (1995) and Ali et al. (2000) had a lower reports than that of the present study, their reported prevalences were 33.3% and 28.8% respectively. Prevalence reported by the present study is higher than the prevalence obtained by several researchers worldwide which ranged from 25 to 51.6%. (Karadag et al. 2013; Seyrafian et al. 2006; Gil et al. 2013; Hawash et al. 2015). Higher rates of infection among hemodialysis patients in the present study may be explained by the higher prevalence of parasitic infection in the local community of Qena Governorate (Zaytoun et al. 2013). Environmental, climatic, sanitary factors and sample size may contribute to the difference of results.

Cryptosporidium spp. was detected in 40% (60/150) of hemodialysis patients and in 6% (3/50) of healthy controls. Similar results were obtained in Sohag Governorate, Egypt, by El Nadi and Taha who found that the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. among 50 hemodialysis patients was 48% (El-Nadi and Taha 2004). Ali et al. (2000) reported 15% and 5% prevalence rates of Cryptosporidium spp. among 120 hemodialysis patients and control group in Zagazig Governorate, Egypt, respectively.

Studies had been conducted in different countries reported lower prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in hemodialysis patients. In Saudi Arabia, Hawash et al. (2015) found that the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection among chronic kidney disease patients and healthy controls was 8% and 6% respectively. Similar results, were reported in Iran by Omrani et al. (2015) who found that the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection among 85 hemodialysis patients was of 11.5%. In Turkey Karadag et al. examined 142 hemodialysis patients and found that the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection was 2.1% (Karadag et al. 2013). Similar to the latter results, Kulik et al. (2008) reported Cryptosporidium infection prevalence of 4.7% among 86 hemodialysis patients in brazil.

In the present study, gender and residence cannot be considered as a risk factor for development of intestinal protozoal infections in hemodialysis patients. These results coincide with the results obtained by done by (Turkcapar et al. 2002; Omrani et al. 2015).

Conclusion

In Egypt, few studies had reported the prevalence of Cryptosporidiosis in chronic renal patients. Cryptosporidium infection should be suspected in all cases of prolonged watery diarrhea in CKD patients and stool samples should be examined using special stains as cold modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining to receive the appropriate medications and help to improve their quality of life.

Author’s contribution

AME and MMT conceived the idea. YF, AME and MMT collected and examined the samples. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, preparation of the manuscript and approval the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abaza SM, Makhlouf LM, El-Shewy KA, El-Moamly AA. Intestinal opportunistic parasites among different groups of Immunocompromised hosts. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1995;25:713–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MS, Mahmoud LA, Abaza BE, Ramadan MA. Intestinal spore-forming protozoa among patients suffering from chronic renal failure. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2000;30:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash LR, Orihel TC. Atlas of human parasitology. 2. Chicago: American Society of Clinical Pathologists Press; 1984. pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Azami M. Prevalence of cryptosporidium infection in cattle in Isfahan, Iran. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2007;54:100–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azami M, Hejazi S. Cryptosporidium and methods of diagnosis. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baiomy AM, Mohamed KA, Ghannam MA, Shahat SA, Al-Saadawy AS. Opportunistic parasitic infections among immunocompromised Egyptian patients. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2010;40:797–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cryptosporidiosis: an assessment of chemotherapy of males with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chonchol M. Neutrophil dysfunction and infection risk in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2006.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Nadi N, Taha A. Intestinal parasites detected haemodialysis patients in Sohag University Hospitals. El-Minia Medical Bulletin. 2004;15(2):233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LS (2001) Diagnostic medical parasitology, 4th edn. p 723

- Gil F, Barros F, Maxlene J, Macedo Nazaré A, Júnior GE, Carmelino Redoan, Haendel Roseli Busatti, Gomes Maria A, Santos Joseph FG. Prevalence of intestinal parasitism and associated symptomatology among hemodialysis patients. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2013;55(2):69–74. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux G, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Dhondt A, Vanholder R. Review of protein-bound toxins, possibility for blood purification therapy. Blood Purif. 2013;35(1):45–50. doi: 10.1159/000346223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawash YA, Dorgham L, El AMA, Sharaf OF. Prevalence of intestinal protozoa among Saudi patients with chronic renal failure: a case-control study. J Trop Med. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/563478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter P, Nichols G. Epidemiology and clinical features of cryptosporidium infection in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:145–154. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.145-154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karadag G, Tamer GS, Dervisoglu E. Investigation of intestinal parasites in dialysis patients. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:714–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik RA, Falavigna DLM, Nishi L, Araujo SM. Blastocystis spp. and other intestinal parasites in hemodialysis patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:338–341. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702008000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P, Soave R. Three-step stool examination for cryptosporidiosis in 10 homosexual men with protracted watery diarrhea. J Infect Dis. 1983;147(5):824–828. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.5.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P. Laboratory diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis. J Postgrad Med. 2002;48(3):217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin DM, and Brooke MM (1982) Centrifugal sedimentation—ether method, pp 103–109. In: Laboratory procedures for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites. Health and human services publication no. 82-8282. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C

- Mohaghegh MA, Jafari R, Ghomashlooyan M, Mirzaei F, Azami M, Falahati M, et al. Soil contamination with oocysts of Cryptosporidium spp in Isfahan, Central Iran. Int J Enteric Pathog. 2015;3:e29105. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi-Manesh R, Hosseini-Safa A, Sharafi S, et al. Parasites and chronic renal failure. J Renal Inj Prev. 2014;3:87–90. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2014.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocak S, Eskiocak A. The evaluation of immune responses to hepatitis B vaccination in diabetic and non-diabetic haemodialysis patients and the use of tetanus toxoid. Nephrology. 2008;13:487–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omrani VFI, Fallahi SH, Rostami A, Siyadatpanah A, Barzgarpour G, Mehravar S, Memari F, Hajialiani F, Joneidi Z. Prevalence of intestinal parasite infections and associated clinical symptoms among patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Infection. 2015;43(5):537–544. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyrafian S, Pestehchian N, Kerdegari M, Yousefi HA, Bastani B. Prevalence rate of cryptosporidium infection in hemodialysis patients in Iran. Hemodial Int. 2006;10:375–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, McAlister F, Garg AX. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2034–2047. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkcapar N, Kutlay S, Nergizoglu G, Atli T, Duman N. Prevalence of cryptosporidium infection in hemodialysis patients. Nephron. 2002;90:344–346. doi: 10.1159/000049072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar BLP. Cryptosporidium. In: Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5edn. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 2903–2912. [Google Scholar]

- Zaytoun S, AbdElla OH, Ghweil AA, Hussien SM, Ayoub HA, Taha AM. Prevalence of intestinal parasitosis among male youth in Qena Governorate (Upper Egypt), and its relation to socio-demographic characteristics and some morbidities. Life Sci J. 2013;10(3):658–663. [Google Scholar]