Abstract

Purpose

To identify the development and progression of macular retinal pigment epithelial atrophy in eyes with neovascular (CNV) age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and to correlate with visual acuity (VA)

Design

Cohort study

Participants

Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) participants with intermediate AMD enrolled in a randomized controlled clinical trial of oral supplements. Analyses were conducted in the subset of AREDS2 participants who were also enrolled in the fundus autofluorescence ancillary (FAF) ancillary study.

Methods

Color photographs and FAF images were evaluated in eyes that developed CNV. Presence of geographic atrophy (GA) prior to the incidence of CNV and the development of macular atrophy following incident CNV were assessed. Areas of hypoautofluorescence representing atrophy were measured for area and macular involvement. Enlargement rate of atrophy and change in visual acuity over time were analyzed.

Main Outcome Measures

incidence and enlargement rate of atrophy and VA changes in eyes with incident CNV

Results

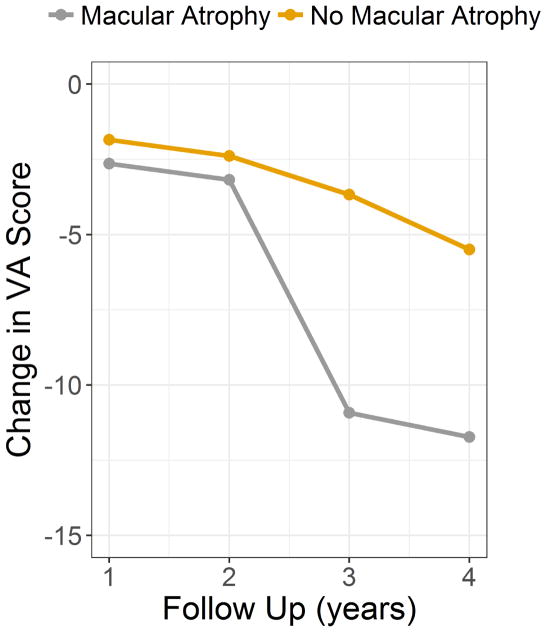

Incident CNV developed in 334 (9.2%) of eyes evaluated in the AREDS2 FAF substudy. Of these, 40% had macular atrophy at incidence of CNV with half of these attributable to pre-existing GA. Atrophy developed in 14.7 % of eyes over 4 years of follow-up. Mean area of atrophy was largest in eyes with pre-existing GA and CNV (5.17 mm2, p<0.001), and atrophy involved the center of the macula in > 65% of eyes. Mean VA letter score at the annual visit in which CNV was documented was similar in the three groups with atrophy; eyes with CNV and pre-existing GA, incident atrophy at the first visit with CNV, and atrophy during follow up (60 letters). Enlargement rate of atrophy was also similar in eyes in the three groups (1.23 – 1.86 mm2, p = 0.47). Eyes with macular atrophy lost more visual acuity compared to eyes without atrophy, particularly after 2 years of follow-up (−10.9 vs. – 3.6 letters, p = 0.07).

Conclusion

Atrophy is commonly seen in neovascular AMD and often can be attributed to pre-existing GA. Macular atrophy and GA appear to be a continuum of the same disease process and are both associated with poor vision.

Introduction

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in developed countries.1, 2 The natural history of AMD involves development of drusen and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) changes that may evolve to geographic atrophy (GA), a late or an advanced form of AMD.3, 4 The disease progression can be intercepted by neovascular AMD, an exudative form of the disease, resulting in significant vision loss. While there are currently no treatments for GA, approved drugs are available for neovascular AMD in the form of intraocular anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections. The pivotal phase 3 trials for anti-VEGF treatments have shown that intraocular anti-VEGF administration can prevent vision loss and improve mean visual acuity during the first 1 to 2 years. 5–7 Visual acuity gains were however not maintained at 5 years.8 Development of subfoveal RPE atrophy and photoreceptor loss appears to be an important reason for decrease in visual acuity over time. 9,10–12 Since eyes with CNV may be complicated by RPE and photoreceptor loss, the term macular atrophy has been suggested as a more preferred term to describe these regions of atrophy..13, 14 It is currently unclear if macular atrophy is primarily a late sequela of the neovascular disease process, a consequence of anti-VEGF treatment or an end result combining pre-existing GA and macular atrophy due to resolution of exudative process.

Various neovascular components in a treated eye including fibrosis, hemorrhage, fibrosis, residual fluid and the neovascular lesion itself complicate the identification of atrophy. A combination of color photographs, fundus autofluorescence (FAF) images, fluorescein angiograms (FA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) images have been used in clinical trials to identify atrophic changes in CNV. 14–17 FAF imaging is a noninvasive method for identifying changes to fluorophores, primarily lipofuscin within the RPE. Atrophy of the RPE can be clearly identified by areas of decreased FAF signal. These high contrast images improve the accuracy of identification and measurement of areas of RPE atrophy. 18

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) provides a unique opportunity to assess the development of macular atrophy in eyes with incident CNV. Availability of retinal images before and after the development of CNV allows examination of the temporal profile of atrophy in the setting of neovascular AMD. The purpose of our study was to investigate the prevalence of macular atrophy in eyes with recently diagnosed neovascular AMD and distinguish cases with atrophy before CNV onset, cases with atrophy concomitant to CNV diagnosis and cases with atrophy developing during follow-up of CNV.

Methods

The AREDS2 was a National Eye Institute-sponsored trial completed in 2013 with a goal of evaluating the effect of oral supplements on progression to late AMD. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each clinical site and written informed consent for the research was obtained from all study participants. The research was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the Health Portability and Accessibility Act.

Participants with either bilateral large drusen or late AMD in one eye and large drusen in the fellow eye were enrolled in the AREDS2 study. The study design and baseline characteristics of the primary AREDS2 dataset have been described elsewhere.19 Development of CNV or GA was a study outcome. Eyes developing CNV were treated using standard of care options and continued follow-up in the AREDS2 trial. Stereoscopic 3 field color photographs were obtained annually. The AREDS2 FAF substudy collected FAF images of subjects in participating clinical sites at annual visits. AREDS2 participating clinical sites joined the FAF substudy between 2007–2013, as the FAF imaging equipment became available at the clinical sites. Participants enrolled in the AREDS2 FAF ancillary study who developed CNV during the study period were included in this analysis. Neovascular AMD was confirmed from color photographs by the presence of two or more features of exudation including subretinal fluid, serous or fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment, subretinal or sub RPE blood characteristic of neovascular AMD, hard exudates and fibrous tissue. In addition, verification of CNV by clinical examination at the study site or treatment for CNV was also considered as confirmation of a neovascular event.

Both color and FAF images were evaluated by trained and certified evaluators at the Fundus Photograph Reading Center, Madison, WI. Images were assessed for features of atrophy at the annual visit where CNV was first identified, the previous visits and all follow-up visits The incident CNV visit and all subsequent followup images were evaluated for areas of hypoautofluorescence and correlated with color photographs for the presence of atrophy. The details of image evaluation have been described in an earlier report. 18 In summary, all color photographs were evaluated for the detailed AREDS severity score. In addition, RPE atrophy on fundus photography was analyzed using the AREDS definition(a minimum size of drusen circle I2 or 0.15 mm2 and at least two of the following criteria are met: roughly round or oval shape, sharp margins, and visibility of underlying large choroidal vessels).4

On FAF, RPE atrophy is typically visualized as a uniform region of well-defined homogenously dark area with a minimum size of drusen circle I–2( area 0.15 mm2). Software planimetry tools were used to measure areas of hypoautofluorescence and the distance of the nearest border of hypoautofluorescence to the macula ( figure 1). The center of the macula was assumed to be involved if the hypoautofluorescent lesion merged with the darkness at the center of the macula. On FAF images, areas of hypoautofluorescence were designated as atrophy only if the colors had atrophy in the corresponding area and there was an absence of pathological changes that could cause blocked autofluorescence, such as blood, fibrosis, hard exudates and choroidal new vessel membrane. All eyes in the sample had color and FAF images for the annual visit before the onset of neovascularization. At the visit preceding CNV identification, any abnormalities in the FAF images including the presence of reticular pseudodrusen were documented. Reticular pseudodrusen were identified as well defined characteristic hypoautofluorescent pattern of dots or ribbons. All color photographs were also evaluated for the detailed AREDS severity scale. 4, 20 Visual acuity letter scores were available for all annual visits.

Figure 1.

Color photograph and autofluorescence image in an eye with neovascular AMD with atrophy outlined

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are provided. Mean and standard deviations are presented for continuous measurements and frequency tabulations for categorical variables are provided. Comparison between groups is calculated using the Kruskal Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Results

The AREDS2 FAF substudy had 4328 eyes of 2509 participants at risk of developing advanced AMD, either GA or CNV. Over the course of the study, 334 eyes (9.2%) developed CNV. The visit where CNV was first identified by the reading center was denoted as the event visit. At the event visit, hypoautofluorescence representing macular atrophy was seen in 137 (41%) eyes. Of these, GA was visible at the preceding visit in 69 (20.6%) eyes. Follow up of eyes without atrophy at CNV event showed development of atrophy in 38 (11.3%) eyes by the end of two years and 49 (14.6%) eyes by 4 years. Two year follow-up was available in 175 eyes and four year follow-up was limited to 68 eyes.

The breakdown and imaging characteristics of macular atrophy was examined in three groups; eyes with pre-existing GA, eyes with macular atrophy at event visit and eyes developing macular atrophy at follow-up are described in table 1 and figure 3. Eyes with pre-existing GA had the largest area of atrophy at the event visit as well as at follow up compared to the other groups. In over 2/3rd of the eyes across all 3 groups, atrophy involved the center of the macula. Reticular pseudodrusen was equally present in all three groups (15 – 19%). AMD status preceding the neovascular event was evaluated using the AREDS severity scale. Eyes with pre-existing GA had a severity scale of 9 or 10 indicating non-central or central GA respectively. There was no difference in the distribution of AREDS scale between the other two groups; eyes with macular atrophy at event vs. those that developed macular atrophy at follow up. The majority of eyes were in the intermediate category of AMD scale (levels 5–8).

Table 1.

| Pre-Existing geographic atrophy | Macular atrophy at event visit | New macular atrophy at follow-up | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number ( %) | 69 (20.6%) | 68 (20.4%) | 49 (14.7%) | NA |

| Mean Area in mm2 (SD) | 5.17 (4.56) | 2.46 (3.04) | 3.25 (4.57) | 0.0001 |

| Center of macula involved n (%) | 50 (72.5 %) | 46 (67.6%) | 33 (67.3%) | 0.78 |

| Reticular autofluorescence n(%) | 11 (15.9%) | 13 (19.1%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.87 |

| AMD severity levels preceding

neovascular event Early (levels 1–4) Intermediate (5–8) GA (9, 10) |

NA | |||

| 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1(2%) | ||

| 0 (0%) | 68(100%) | 48 (98%) | ||

| 69 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Mean visual acuity letter score at event visit (SD) | 60.44 (24.01) | 60.31 (20.17) | 60.82 (24.82) | 0.73 |

| Enlargement rate mm2 per year (SD) | 1.86 ( 2.18) | 1.36 (1.76) | 1.23 (1.78) | 0.47 |

| Enlargement rate mm per year (SD) | 0.39 (0.44) | 0.36(0.44) | 0.35(0.41) | 0.88 |

Figure 3.

Flow chart showing the incidence of atrophy in eyes with neovascular AMD in the AREDS2 study

Enlargement rate of atrophy in the three groups was compared to that of eyes with pure GA uncomplicated by CNV available in the AREDS2 dataset (table 1). 18 Eyes with pre-existing GA and CNV had greater annual enlargement rates (1.86mm2 +/− 2.18) compared to eyes with GA alone (1.25 mm2 +/− 1.73) although the difference was not significant (p= 0.25 ). Eyes with macular atrophy at event visit had enlargement rate of 1.36mm2+/− 1.76 and those that developed atrophy at follow up had an enlargement rate of 1.23mm2 +/− 1.78( p 0.61 ). Square root-transformed enlargement rates are shown in table 1 and are similar between the three groups. Figure 4 compares the change in the area of atrophy in eyes with pure GA without CNV (GA only), CNV with pre-existing GA (GA and CNV), and neovascular AMD without pre-existing GA (CNV only). The baseline area of atrophy in eyes with pure GA and those with both GA and CNV is similar ( 5.03mm2 vs. 5.17 mm2). However the change in area over time trends towards being larger in eyes with both GA and CNV, until 3 years of follow-up (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Change in area of atrophy over time in eyes with pure GA, GA and neovascular AMD (pre-existing GA) and eyes with neovascular AMD alone (no pre-existing GA)

Visual acuity at the time of the event was similar in the three groups (table 1). All eyes, irrespective of atrophy status, had a mean decrease in vision of 8 (SD = 16.4) letters at the time of development of neovascularization. Figure 5 shows change in vision over time in eyes with CNV with and without atrophy over time. The mean change in vision in eyes with and without macular atrophy at 2 years was similar at −3.2 (SD 15.93) letters and −2.4 (SD 12.07) letters (p= 0.66). By 3 years of follow-up, the difference between the two groups had increased to −10.9 (SD 21.4) letters in eyes with atrophy and −3.7 (SD16.9) letters in eyes without atrophy (p 0.07).

Figure 5.

Change in visual acuity in eyes with neovascular AMD with and without macular atrophy over time

Discussion

What might be regarded as macular atrophy is not necessarily late sequelae of CNV because GA is present at the onset of disease in about 40% of eyes when assessed with FAF imaging in the AREDS2 dataset. This may be an underestimate because the exudative process, such as subretinal fluid and blood, may obscure areas of atrophy in images. Interestingly, almost half the eyes presenting with atrophy at the time of neovascular event had pre-existing GA. Atrophy developed at follow up in almost 15% of eyes that did not have atrophy at event by 2 years. Other studies using FAF imaging for identification of macular atrophy have shown similar results with baseline atrophy in 35–40% of eyes with neovascular AMD and 15–17% of eyes developing atrophy at followup.14, 21 A limited number of participants in the MARINA/ANCHOR and HORIZON trials were followed up for seven years with FAF imaging and found to have atrophy in a 100% of eyes.16

In the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials (CATT), using color photographs and fluorescein angiograms, atrophy was present at baseline in 7.3% eyes with 17% developing atrophy by year 2 and 38% by year 5. 22, 23 The rates of baseline atrophy are lower than the AREDS2 dataset because eyes with subfoveal GA were excluded from the CATT study.24 In addition, FAF imaging is possibly more sensitive to identifying atrophy than the modalities used in CATT study. Due to the annual visit schedule of AREDS2, CNV could have developed anytime in the previous 11 months before reading center documentation of the event, which may have led to differences in the classification of atrophy onset. Development of atrophy at follow up is comparable between the two datasets at two years. Due to a limited number of participants with a four year follow up in the AREDS2 FAF ancillary study, long-term comparison is not possible.

Enlargement rate of macular atrophy in the AREDS2 dataset is comparable to the CATT study (1.52 mm2 in both datasets). The temporal profile of the dataset allowed for a distinction between macular atrophy with pre-existing GA and “de novo” atrophy. Macular atrophy with pre-existing GA is larger in size and tends to more rapidly enlarge than macular atrophy de novo. The annual growth rates of atrophy are not statistically significantly different in eyes with GA alone and GA with CNV (table 1) although the slope of enlargement is larger for eyes with both GA and CNV (figure 4). OCT angiography studies have shown choriocapillaris nonperfusion in both GA and macular atrophy.25, 26 Nonperfusion is more extensive in macular atrophy compared to GA and extends outside the areas of visible atrophy. The addition of the neovascular process to an already damaged RPE and choroidal vasculature could potentially result in worsening of the disease. Treatment of eyes with dual disease has a worse prognosis due to potential rapid progression of atrophy.

Presence of atrophy at baseline and development of atrophy at follow-up have both been shown to be predictors of poor visual prognosis.9, 27 The baseline visual acuity in the AREDS2 dataset was similar in eyes with and without atrophy. However, the decrease in vision over time was more pronounced in eyes with atrophy, particularly after 2 years. The CATT study showed that visual gains in eyes treated with anti VEGF agents were not maintained after 2 years. With almost half of participants presenting with atrophy at event and with the majority involving the center of the macula, it is not surprising that these participants have worse vision compared to those without atrophy. Identification of macular involvement by hypoautofluorescence can be overcalled in blue light FAF images due to the intrinsic blockade of the macula.28 OCT imaging was unavailable in this study to clearly identify foveal involvement. Other limitations of the study include lack of fluorescein angiographic confirmation of CNV. Therefore, it was difficult to identify the location of the atrophy in relation to the CNV. Atrophy assessment in the presence of exudative lesions of CNV can be challenging and should ideally be done with multimodal imaging. Particularly with autofluorescence imaging, hypoautofluorescence could be due to blocked signal or RPE death. The grading method was conservative and required confirmation of any potential lesions causing blocked autofluorescence from color photographs. Areas of blocked autofluorescence due to fibrosis or the neovascular lesion were not considered as atrophy despite the possibility of underlying atrophic changes. The strength of the current study is the broad spectrum of participants who have contributed to further our understanding of the evolution and progression of atrophy in the setting of neovascular AMD. The dataset is not restricted by enrollment criteria for clinical trials and has information on the status of the eye before the development of neovascular disease. The results show that a multifactorial etiology plays a role in the development of atrophy in eyes with neovascular AMD. Atrophy may be present before the onset of neovascular AMD (traditionally called geographic atrophy), at the onset of neovascular AMD (“de novo” macular atrophy) and after treatment of neovascular AMD. Geographic atrophy and macular atrophy appear to be a continuum of the same spectrum of disease and therefore impossible to differentiate in most eyes with CNV. Irrespective of its origin, the presence of atrophy is an indicator of poor visual prognosis in eyes with neovascular AMD.

The AREDS AMD severity scale identifies central GA and neovascular AMD as two distinct endpoints with no overlap. However, the development of neovascular AMD in eyes with GA is a known entity with incidence in the Beaver Dam Eye study at 10.9% and the Blue Mountain Eye Study at 22% over 5 years.26, 27 Recent advanced imaging studies using OCT angiography have, in fact, shown unsuspected quiescent neovascularization adjacent to areas of GA.28, 29 Conversely, the development of GA in eyes with neovascular AMD has been rarely studied before anti-VEGF therapy as we were unable to identify atrophy in the presence of fibrosis, pigment and photocoagulation scars. It may be that the development of atrophy is the final common pathway of AMD, with the neovascular process intercepting the pathway in some eyes.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Color and autofluorescence images showing GA (top) in an eye that developed neovascular AMD at the next annual visit (bottom). It is difficult to distinguish pre-existing GA from macular atrophy in eyes with neovascular AMD without information from preceding visits.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: AD, RT, RPD, BB Supported in part by an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York.

Footnotes

Presented at the AAO Annual Meeting 2016

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–85. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, Nash SD, et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and associated risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:750–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, Segal P, Klein BE, Hubbard L. The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1128–34. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis MD, Gangnon RE, Lee LY, et al. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 17. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1484–98. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:1432–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept (VEGF Trap-Eye) in Wet Age-related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 119:2537–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire MG, Martin DF, Ying G-s, et al. Five-Year Outcomes with Anti–Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 123:1751–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Toth CA, Daniel E, et al. Macular Morphology and Visual Acuity in the Second Year of the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:865–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelfattah NS, Zhang H, Boyer DS, et al. Drusen Volume as a Predictor of Disease Progression in Patients With Late Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Fellow Eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1839–46. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schutze C, Wedl M, Baumann B, Pircher M, Hitzenberger CK, Schmidt-Erfurth U. Progression of retinal pigment epithelial atrophy in antiangiogenic therapy of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:1100–1114.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfeld PJ, Shapiro H, Tuomi L, Webster M, Elledge J, Blodi B. Characteristics of patients losing vision after 2 years of monthly dosing in the phase III ranibizumab clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelfattah NS, Zhang H, Boyer DS, Sadda SR. PROGRESSION OF MACULAR ATROPHY IN PATIENTS WITH NEOVASCULAR AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION UNDERGOING ANTIVASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR THERAPY. Retina. 2016;36:1843–50. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelfattah NS, Al-Sheikh M, Pitetta S, Mousa A, Sadda SR, Wykoff CC. Macular Atrophy in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration with Monthly versus Treat-and-Extend Ranibizumab: Findings from the TREX-AMD Trial. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danis RP, Lavine JA, Domalpally A. Geographic atrophy in patients with advanced dry age-related macular degeneration: current challenges and future prospects. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2159–2174. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S92359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:915–24.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuehlewein L, Dustin L, Sagong M, et al. Predictors of Macular Atrophy Detected by Fundus Autofluorescence in Patients With Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration After Long-Term Ranibizumab Treatment. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016;47:224–31. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160229-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domalpally A, Danis R, Agron E, Blodi B, Clemons T, Chew E. Evaluation of Geographic Atrophy from Color Photographs and Fundus Autofluorescence Images: Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Report Number 11. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2401–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chew EY, Clemons T, SanGiovanni JP, et al. The Age-related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Study Design and Baseline Characteristics (AREDS2 Report Number 1) Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2282–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danis RP, Domalpally A, Chew EY, et al. Methods and Reproducibility of Grading Optimized Digital Color Fundus Photographs in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2 Report Number 2) Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2013;54:4548–4554. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thavikulwat AT, Jacobs-El N, Kim JS, et al. Evolution of Geographic Atrophy in Participants Treated with Ranibizumab for Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology retina. 2017;1:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunwald JE, Pistilli M, Ying GS, Maguire MG, Daniel E, Martin DF. Growth of geographic atrophy in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:809–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunwald JE, Pistilli M, Daniel E, et al. Incidence and Growth of Geographic Atrophy during 5 Years of Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, Grunwald JE, Fine SL, Jaffe GJ. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1897–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kvanta A, Casselholm de Salles M, Amren U, Bartuma H. OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY OF THE FOVEAL MICROVASCULATURE IN GEOGRAPHIC ATROPHY. Retina. 2017;37:936–942. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takasago Y, Shiragami C, Kobayashi M, et al. MACULAR ATROPHY FINDINGS BY OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY COMPARED WITH FUNDUS AUTOFLUORESCENCE IN TREATED EXUDATIVE AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION. Retina. 2017 doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001980. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ying G-s, Maguire MG, Daniel E, et al. Association of Baseline Characteristics and Early Vision Response with Two-Year Vision Outcomes in the Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials (CATT) Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2523–2531.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf-Schnurrbusch UE, Wittwer VV, Ghanem R, et al. Blue-light versus green-light autofluorescence: lesion size of areas of geographic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9497–502. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.