Abstract

Although the last decade has seen a proliferation of research on mental illness stigma, lack of consistency and clarity in both the conceptualization and measurement of mental illness stigma has limited the accumulation of scientific knowledge about mental illness stigma and its consequences. In the present article, we bring together the different foci of mental illness stigma research with the Mental Illness Stigma Framework (MISF). The MISF provides a common framework and set of terminology for understanding mechanisms of mental illness stigma that are relevant to the study of both the stigmatized and the stigmatizer. We then apply this framework to systematically review and classify stigma measures used in the past decade according to their corresponding stigma mechanisms. We identified more than 400 measures of mental illness stigma, two thirds of which had not undergone any systematic psychometric evaluation. Stereotypes and discrimination received the most research attention, while mechanisms that focus on the perspective of individuals with mental illness (e.g., experienced, anticipated, or internalized stigma) have been the least studied. Finally, we use the MISF to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of mental illness stigma measurement, identify gaps in the literature, and provide recommendations for future research.

Keywords: stigma, mental illness stigma, Mental Illness Stigma Framework

“A sustainable, coherent theory of stigma can improve…stigma research and intervention planning because how we define stigma structures our understanding of how to measure it, and how to design and evaluate interventions”

(Deacon, 2006 pg. 419)

“The terminology we use…should be clear, precisely defined, and used consistently to aid unambiguous clinical and scientific communication and promote clearer appraisal of, and generalizations from, empirical findings”

(Kelly, 2004 pg. 80)

Mental illness stigma is as a major obstacle to well-being among people with mental illness (PWMI). According to findings from the most recent nationally representative study of public attitudes toward mental illness in the U.S., only 42% of Americans aged 18–24 believe PWMI can be successful at work, 26% believe that others have a caring attitude toward PWMI, and 25% believe that PWMI can recover from their illness (NAMI-GC, 2013; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2008). A robust body of evidence demonstrates that PWMI experience discrimination in nearly every domain of their lives, including employment (Farina & Felner, 1973; Link, 1987; Stuart, 2006), housing (Corrigan et al., 2003; Farina, Thaw, Lovern, & Mangone, 1974), and medical care (Thornicroft, Rose, & Kassam, 2007). Experiences of stigma are associated with increased symptom severity (e.g., Boyd, Adler, Otilingham, & Peters, 2014), decreased treatment seeking (e.g., Corrigan, 2004) and treatment non-adherence (e.g., Sirey et al., 2001).

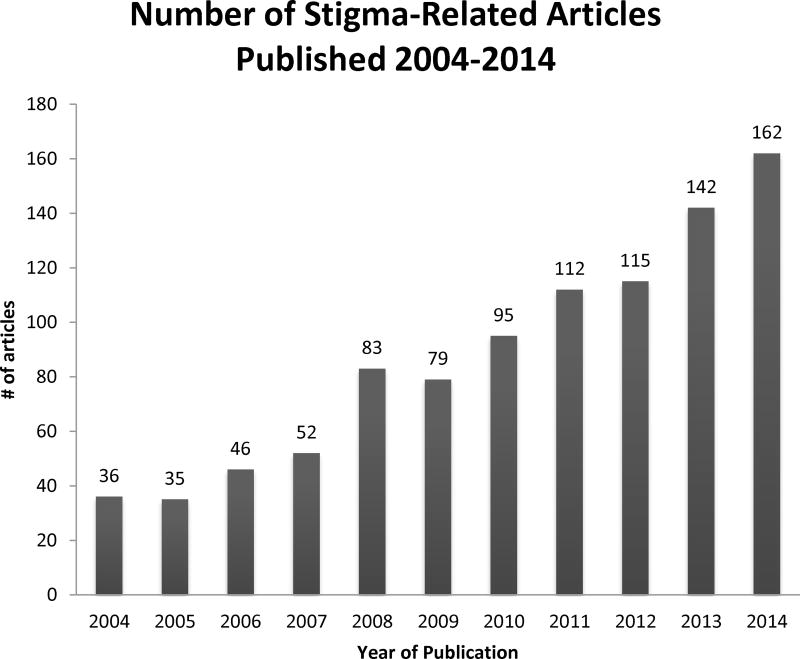

Given the prevalence of mental illness and the deleterious effects of stigma, mental illness stigma has been a widely studied research topic in a variety of disciplines, including psychology, sociology, public health, and medicine. Beginning with Erving Goffman’s (1963) seminal essay Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, research on stigma has continued to grow each year, with the majority of stigma research occurring in the last decade (Bos, Pryor, Reeder & Stutterheim, 2013). Across disciplines, but especially within the field of psychology, researchers have been primarily concerned with examining mental illness stigma at the individual level (Link & Phelan, 2001). As Figure 1 demonstrates, the number of published, peer-reviewed mental illness stigma articles appearing in searches of PubMed, PsycInfo/EBSCO, and Web of Science has steadily increased each year for the past ten years. As the psychological research on mental illness stigma has progressed, the stigma construct has been parsed into a number of different constructs, or mechanisms. Borrowing from the work of Link (2001), we use the term “stigma mechanism” throughout the present article to emphasize that these different constructs represent ways in which individuals respond to having, or not having, a mental illness (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, 2009; Link, 2001).

Figure 1.

Number of Stigma-Related Peer-Reviewed Publications appearing in searches of EBSCO/PsycInfo databases, PubMed, and Web of Science, 2004–2014

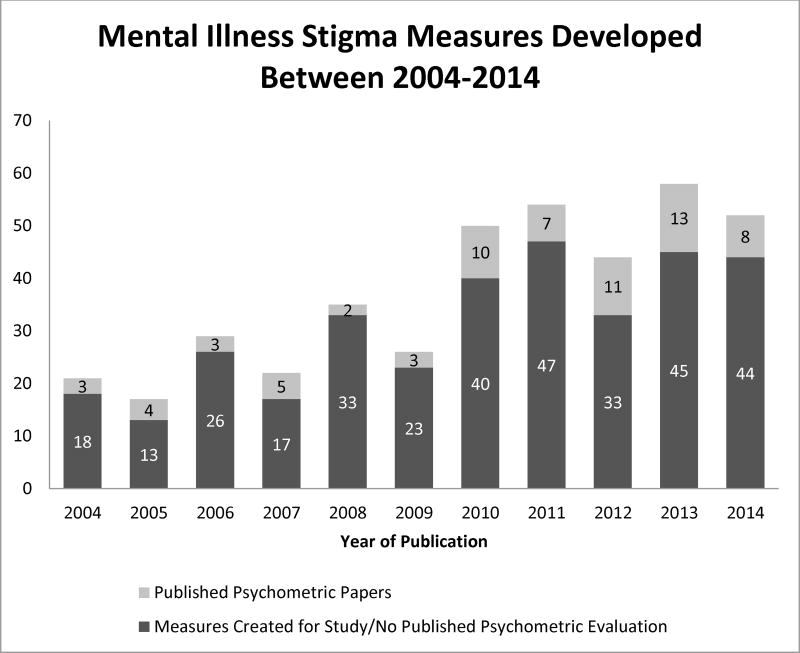

The proliferation of research on mental illness stigma mechanisms in the psychological literature has been accompanied by a sharp increase in stigma measures. In 2004, Link and colleagues published a review of mental illness stigma measures, with guidelines and suggestions for researchers interested in studying and measuring mental illness stigma. In addition to describing the already substantial number of stigma measures that existed at that time, they identified a number of gaps in stigma measurement, including the need for measures related to the experiences of PWMI (e.g., internalized stigma). As Figure 2 demonstrates, more than 400 new measures of mental illness stigma have been developed since 2004. The overabundance of measures may be attributed, in part, to the lack of consistency in how stigma mechanisms are defined, which may make it difficult for researchers to identify existing measures that meet their needs. Such inconsistencies in terminology and measurement make it difficult to evaluate the state of the field, and in turn, may hinder efforts to develop interventions to reduce or eliminate mental illness stigma.

Figure 2.

Mental Health Stigma Measures Identified in searches of EBSCO/PsycInfo databases, PubMed, and Web of Science, 2004–2014

Aims of the Review

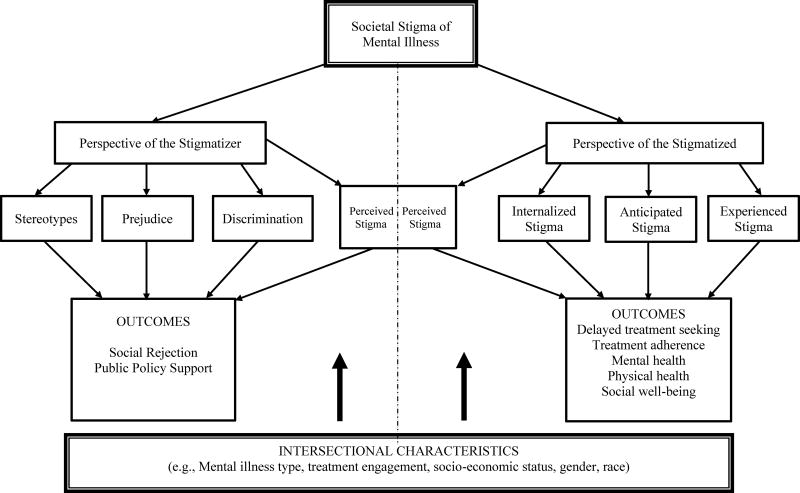

In the present article, we first review existing limitations and challenges currently facing the mental illness stigma literature with a primary focus on the psychological literature. Next, we bring together the different foci of mental illness stigma research in an overarching conceptual framework for understanding how individuals experience stigma, the Mental Illness Stigma Framework (Figure 3). After overviewing key aspects of this framework—and their associated benefits for organizing mental illness stigma research, we demonstrate the usefulness of this framework by applying it— to systematically review and classify mental illness stigma measures that have appeared in the literature since Link and colleagues’ (2004) previous measure review. We then identify gaps in the literature and limitations with the measurement of mental illness stigma, and provide recommendations for future research.

Figure 3.

The Mental Illness Stigma Framework

Because stigma is a social process that manifests at multiple levels, researchers in fields such as sociology and anthropology have also developed theoretical perspectives on mental illness stigma. Many of these theories consider the processes whereby mental illness stigma is socially constructed and reinforced. Consequently, researchers from other fields have studied other forms of stigma including structural stigma (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013) as well as cultural manifestations of stigma (e.g., Abdullah & Brown, 2011; Yang et al., 2007). In the present review, we focus our attention on individual-level experiences of stigma, and draw from a substantial body of primarily psychological literature to further understanding of how individuals experience, and are impacted by, mental illness stigma. In the discussion section, we briefly consider how other forms of stigma may contribute to our larger understanding of how mental illness stigma operates.

Limitations and Challenges of the Mental Illness Stigma Literature

Clear and consistent terminology is important to all fields of inquiries. A number of researchers have pointed out the confusion, complexity, and/or lack of clarity in the mental illness stigma literature (e,g., Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006; Brohan et al., 2010; Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Thornicroft, 2008). This lack of conceptual clarity is not unique to mental illness stigma research. In reference to the HIV/AIDS stigma literature, Deacon (2006) noted that “the concept of stigma has suffered from ‘conceptual inflation’ and a consequent lack of analytical clarity” (pg. 419). For example, the term “stigma” is often used to refer to “both the stigmatizing beliefs themselves and the effects of these stigmatization processes” (p. 419). The same can be said for the mental illness stigma literature, and even the broader stigma construct itself, which has been criticized for its complexity and variability in definitions both within and across disciplines (Link & Phelan, 2001; Pescosolido & Martin, 2015; Phelan, Link, & Dovidio, 2008).

A prominent issue within the mental illness stigma literature is that researchers frequently use different terms to describe the same stigma concepts and the same terms to refer to different constructs. For example, the term perceived stigma is sometimes used to refer to what others term experienced stigma or internalized stigma. The concept of anticipated stigma, as we define it in this article, is sometimes referred to as stigma concerns, stigma apprehension, or stigma consciousness. And the terms internalized stigma and self-stigma are often used interchangeably. This proliferation of terminologies and definitions of mental illness stigma represent a critical barrier to the advancement of mental illness stigma research. A search for articles on experienced stigma may not reveal important research on perceived stigma; a search for anticipated stigma may not reveal articles on stigma concerns, and a search for studies of perceived stigma could produce studies of not only perceived stigma, but also studies of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, as well as experienced or internalized stigma.

Another challenge to the field has been the siloing of research based on the particular type of mental disorder under study. Mental illness encompasses a broad and diverse set of disorders and it is possible that mental illness stigma may manifest slightly differently depending on the type of disorder with which an individual has been labeled. For example, an individual diagnosed with Schizophrenia may be viewed as more dangerous than someone diagnosed with an anxiety or depressive disorder (Feldman & Crandall, 2007). Likewise, because the cause of posttraumatic stress disorder is typically believed to be external rather than internal (i.e., trauma exposure), an individual diagnosed with this disorder is likely to be considered less responsible for their mental illness than an individual diagnosed with a personality disorder.

While a disorder–specific approach to the study of mental illness stigma has a number of benefits, in the present review we have taken a broader approach for several reasons. First, a broad approach can bring together the common threads of the experiences of mental illness stigma. Second, such an approach is consistent with macro-level theories of stigma that cross-cut stigmatized identities (Link & Phelan, 2001; Phelan, Link & Dovidio, 2008; Pescosolido & Martin, 2015), as well as meta-analyses demonstrating that the effects of stigma are similar across a variety of stigmatized conditions (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009) and different mental health disorders (Mak, Poo, Pun, & Cheung, 2007). Third, the feasibility of a broad approach is evidenced by the finding that stigmatization of PWMI is driven by three core stereotypes—dangerousness, rarity, and responsibility—and disorders can be ranked in terms of their level of social rejection (Feldman & Crandall, 2007; Silton, Flannelly, Milstein, & Vaaler, 2011). Finally, van Brakel (2006) argues that the impact of stigma is similar across a variety of health conditions, suggesting that generic stigma measures can provide an accurate assessment of how people experience stigma. This work suggests that a macro-level framework of mental illness stigma could provide much needed clarity to the field of mental illness stigma research.

Another limitation of mental illness stigma literature is that most of the existing stigma models and frameworks do not incorporate stigma concepts that are relevant to both research on the stigmatizer and the stigmatized. Yet, such an approach has important benefits, as the inclusion of the perspective of both individuals who have and do not have mental illness recognizes that experiences and outcomes of stigma are fundamentally shaped by whether the individual possesses the socially devalued characteristic. Classic theories of stigma (Link & Phelan, 2001), as well as theories of intergroup relations (Allport, 1954; Brewer, 2007) emphasize that “separation” is an important component of stigma. The distinction between “us” and “them” is what allows stigma to unfold (Link & Phelan, 2001).

To address some of the limitations of the mental illness stigma literature and guide our review of mental illness stigma measures, we developed the Mental Illness Stigma Framework (MISF; Figure 3). The development of the MISF was informed by a number of prominent mental illness stigma theories, conceptualizations and definitions, including modified labeling theory (Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout, & Dohrenwend, 1989), Link and Phelan’s (2001) definition of stigma, social cognitive theory of public and self-stigma (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006; Corrigan, Kerr, & Knudson, 2005), Pryor and Reeder’s (2011) four manifestations of stigma, the constructs of anticipated and experienced discrimination (Brohan et al., 2013; Thornicroft et al., 2007), and the construct of internalized stigma (Boyd Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003). Our proposed framework is meant to complement, not replace, existing frameworks, models, or theories. A key benefit of the framework is that by integrating existing definitions and conceptualizations of mental illness stigma through common terminology, we tie together the immense and varied body of mental illness stigma research and delineated the types of stigma that are most important to outcomes for people with and without mental illness, regardless of the specific condition under study.

The Mental Illness Stigma Framework

The top box of the MISF represents the identification of mental illness as a culturally-situated and socially devalued identity. How do individuals understand, respond to, and experience mental illness stigma? The answer to this question depends on whether an individual has experienced a mental illness. Existing research on mental illness stigma at the individual level can be broken down into two major categories: Research focused on the perspective of those doing the stigmatizing, typically the general public, and research focused on those who are on the receiving end of stigmatization, individuals with mental illness (or a history of mental illness). Thus, the MISF separates stigma mechanisms accordingly. Separating stigma mechanisms based on perspective is consistent with existing theories and definitions of stigma, (Bos, et al., 2013; Clement et al., 2015; Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Corrigan, Rafacz, & Rusch, 2011; Link & Phelan, 2001; Martin, Pescosolido, Olafsdottir, & McLeod, 2007; Pescosolido & Martin, 2015; Pryor & Reeder, 2011; van Brakel, 2006).

Perspective of the Stigmatizer

Drawing from the social psychological (Allport,1954; Brewer, 2007; Dovidio, Glick, & Rudman, 2005; Nelson, 2009), mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2005; Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam, & Sartorius, 2007), and broader stigma literature (Bos, Pryor, & Reeder, 2013; Pryor & Reeder, 2011), the three mechanisms that are most relevant to individuals who do not have (or have never had) a mental illness are stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. These three mechanisms represent the cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses people may have to someone who possesses a devalued identity. Stereotypes are beliefs, or “cognitive schemas” about the characteristics and behaviors of groups of individuals (Corrigan, 2005; Dovidio, Hewstone, Glick, & Esses, 2010; Stangor, 2009) and represent the cognitive response to someone with mental illness stigma. The core stereotypes associated with mental illness include dangerousness, rarity, responsibility, incompetence, weakness of character, and dependence (Feldman & Crandall, 2007; Taylor & Dear, 1981).

The affective component of mental illness stigma is reflected in prejudice, defined as the emotional reaction or feelings that people have toward a group or member of a group (Stangor, 2009). Most often, these feelings are negative, although they do not necessarily need to be. The most common forms of prejudice toward PWMI are fear, pity, and anger (Corrigan, 2005; Corrigan, Watson, Warpinksi, & Garcia, 2004). Prejudice is strongly connected to stereotypes. As examples, the stereotype of dangerousness may lead to feelings of fear and the stereotype of incompetence may lead to feelings of pity. Prejudice toward PWMI may also be expressed or experienced as anxiety, leading to awkward interactions (Hebl, Tickle, & Heatherton, 2000) and/or serve as a precursor to the behavioral aspect of stigma, discrimination. Discrimination is defined as the unfair or unjust behaviors directed at PWMI (Allport, 1954; Brewer, 2007). Discriminatory behaviors exist along a continuum from subtle to overt, but which result in the “differential and disadvantaged treatment of the stigmatized” (Pescosolido & Martin, 2015). There are four common types of discrimination directed towards PWMI described in the literature: withholding help, avoidance, segregation, and coercion (Corrigan & Rüsch, 2002; Corrigan & Watson, 2002).

Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination lead to a range of outcomes that affect both people living with and without mental illness. Individuals who endorse stigmatizing attitudes toward PWMI are less likely to support insurance parity (i.e., covering mental illness at the same level as other medical conditions) and increased government funding for mental health treatment (Barry & McGinty, 2014). In the workplace, discrimination can limit the economic opportunities of PWMI. Additionally, these mechanisms prevent people without diagnoses of mental illness from seeking mental health support to avoid gaining the label of mental illness (Corrigan, 2004).

Perspective of the Stigmatized

Three stigma mechanisms are most relevant to PWMI (or people with a history of mental illness): experienced stigma, anticipated stigma, and internalized stigma. Experienced stigma is defined as experiences of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination from others in the past or present (Cechnicki, Angermeyer & Bielańska, 2011; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011; Wahl, 1999) and is sometimes referred to as enacted stigma (Bos et al., 2013). Experienced stigma includes both chronic, day-to-day experiences of unjust or unfair treatment (e.g., interpersonal slights) as well as acute, major experiences (e.g., fired from one’s job), both of which are related to a range of deleterious outcomes among people with stigmatized identities (Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). Anticipated stigma, sometimes referred to as felt stigma (Bos et al., 2013), is defined as the extent to which a person with mental illness expects to be the target of stereotypes, prejudice, or discrimination in the future (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011). Because PWMI are likely aware of the negative stereotypes associated with mental illness and negative ways in which PWMI are treated, they may worry about people viewing them as weak or dangerous, being afraid or avoiding them, or being denied work. PWMI may therefore anticipate stigma even if they have never personally experienced stigma. Finally, we define internalized stigma as the extent to which people endorse the negative beliefs and feelings associated with the stigmatized identity for the self (Bos et al., 2013; Boyd Ritsher et al., 2003; Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006; Link, 1987; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011). In other words, internalized stigma represents the application of negative stereotypes and prejudice to the self. For PWMI, this may involve perceiving that they are dangerous, to be blamed for their illness, are incompetent, or childlike (Taylor & Dear, 1981). Internalized stigma is sometimes referred to as self-stigma, a term which reflects the application of mental illness stigma to the self (Corrigan, Rafacz, & Rüsch, 2011; Corrigan & Rao, 2012). When an individual applies negative stereotypes of mental illness to the self, they may believe they are devalued (Quinn & Earnshaw, 2013), which in turn may lead to increased psychological distress (Ritsher & Phelan, 2004) or decreased self-esteem (Corrigan, et al., 2011; Corrigan & Rao, 2012).

Experienced, anticipated, and internalized stigma are associated with negative outcomes for PWMI. Perceived and anticipated stigma undermine mental illness treatment adherence and initiation (Corrigan, 2004; Sirey et al., 2001). Anticipated and experienced stigma are stressors (Link & Phelan, 2006), which may elicit psychological and physiological stress responses that impact mental and physical health. Internalized stigma is associated with depression, decreased self-esteem, and increased symptom severity (Boyd et al., 2014).

Perceived Stigma

Perceived stigma is the one stigma mechanism in the framework that is shared by both people with and without mental illness. We define perceived stigma as perceptions of societal beliefs (stereotypes), feelings (prejudice), and behaviors (discrimination) toward PWMI (Bos et al., 2013; Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans, & Groves, 2004; Link, 1987). Perceived stigma is distinct from an individual’s own beliefs, feelings, and behaviors about PWMI, which Griffiths and colleagues refer to as personal stigma (and which is captured by the mechanisms of stereotypes and discrimination in the MISF). Research has established the importance of treating personal and perceived stigma as distinct constructs. Griffiths et al. (2008) found that whereas people’s own stigma-related beliefs were associated with greater psychological distress, less previous contact with people with depression, and lower depression literacy, perceived stigma was only associated with psychological distress. Additionally, demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, education, experience with someone with depression, country of birth) explained 22% of the variance in individual’s own stigma-related beliefs, while only explaining 1.6% for perceived stigma.

The extent to which people perceive the stigma of mental illness is shaped by whether they have experienced mental illness. For example, studies have shown a positive relationship between mental illness symptom severity and perceived stigma (Freidl, Piralic, Spitzl, & Aigner 2008; Golberstein, Eisenberg, & Gollust, 2008; Griffiths et al., 2008). Further, perceived stigma is associated with negative outcomes for PWMI. In Link’s (1987) seminal paper examining the negative labeling effects of mental illness, he showed that for PWMI who have been labeled as mentally ill, perceived discrimination and devaluation were associated with a number of negative outcomes associated with employment, earnings, and demoralization (Link, 1987; Link et al., 2004), but this was not the case for PWMI who had never received the label.

Intersectionality

Finally, the MISF recognizes that there is intersectionality in experiences of stigma, a perspective that emphasizes that individuals also live with other characteristics representing privilege and marginalization, and that it is important to take these other characteristics into account in order to understand their lived experiences and outcomes (Cole, 2009; Crenshaw, 1991; hooks, 1990). This perspective therefore allows for commonality in experiences of stigma across all PWMI, while simultaneously emphasizing that individual experiences of mental illness stigma may vary depending on one’s specific mental illness diagnosis, treatment engagement, socio-economic status, gender, race, culture, and/or other characteristics.

Application of the Mental Illness Stigma Framework to Measurement

The proliferation of research on mental illness stigma has been accompanied by a stark increase in stigma measures. While the availability of multiple measures is not inherently problematic, the development of new measures may be inefficient when validated measures of the same construct already exist. The availability and use of so many measures can also present difficulties for researchers trying to draw broad conclusions from the literature. In their meta- analysis of stigma change programs, Corrigan and colleagues (2012) noted that there were 22 different outcome measures in their analysis, assessing a range of attitudes, affects, and behavior intentions. As the choice of measures is tied to how researchers define constructs, the use of so many measures can make it difficult to draw firm conclusions about mental illness research.

Additionally, to the extent that the mental illness stigma measures in use today do not differentiate between stigma mechanisms, researchers may miss opportunities to examine the implications of different stigma mechanisms and may inadvertently dilute or amplify the effects of one particular mechanism by failing to acknowledge that their measure reflects multiple mechanisms. For example, Livingston and Boyd (2010) found a robust negative relationship between internalized stigma, hope, self-esteem and treatment adherence, and a positive association between internalized stigma and symptom severity in their meta-analysis. However, their broad definition of internalized stigma incorporated measures of experienced stigma, anticipated stigma, stereotypes, and perceived stigma. While their findings present a broad picture of the relationship between mental illness stigma and various outcomes, they cannot inform conclusions about the role of internalized stigma as defined by other researchers (Corrigan et al., 2006; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011).

Understanding which stigma mechanisms are being assessed in any given measure is vitally important. Each stigma mechanism may impact people uniquely. For example, a recent meta-analysis of stigma and help-seeking found that internalized stigma predicted help-seeking, whereas perceived, experienced, and anticipated stigma did not (Clement et al., 2015). To move the study of mental illness stigma forward, we need to identify measures that can be used to reliably and validly measure different mechanisms of mental illness stigma (Corrigan & Shapiro, 2010). In the next section, we use MISF to guide a systematic review and evaluation of mental illness stigma measures. We focused our review on the ten year period following Link et al.’s (2004) review of mental illness stigma measures. Unlike previous reviews (e.g., Brohan et al., 2010; Corrigan & Shapiro, 2010; Link et al., 2004), we provide a broad review of measures of mental illness stigma, whether validated or unvalidated, in order to present a comprehensive overview of the state of mental illness stigma measurement.

Method

We conducted a literature search on articles published between 2004 and 2014 using PubMed, EBSCO databases (PsycInfo, Academic Search Premier, Education Full Text, General Science Full Text, PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Social Sciences Full Text, Women’s Studies International), and Web of Science. The search was limited to peer-reviewed, quantitative or empirical manuscripts published in English. Using titles, abstracts, and keywords, we searched for articles containing the keyword stigma and any of the following: mental health, mental illness, schizo*, depress*, anxiety, PTSD, posttraumatic, eating disorder*, anorexia, bulimia, or personality* disorder. We excluded the following keywords: epilepsy, HIV, AIDS, dementia. Next, we checked the reference sections of reviews and meta-analyses articles published in the past ten years (Brohan et al., 2010; Clement et al., 2015, Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Mak, Poon, Pun, & Cheung, 2007; Schomerus & Angermeyer, 2008) and our personal libraries for additional articles.

Screening of Studies

An initial screening of the titles and abstracts of 3901 articles resulted in the identification of 1282 articles that were potentially relevant to our review. The first author reviewed all 3901 articles and a second coder reviewed 1086 articles (35%) to ensure reliability. Coders agreed 95% of the time and all disagreements (n =51) were included in the full-text review. The full-text of each of the 1282 articles was then reviewed to determine if the study contained a mental illness stigma measure. After the full-text review, an additional 326 articles were excluded. In total, 957 articles contained at least one stigma measure. Supplemental Figure S1 contains the PRISMA diagram with the literature search details (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009).

Organizing Measures

For each of the 957 articles, we identified the stigma measure(s) that was used and classified it into one of two categories. The first category represents measures that have been cited in at least one study (not including the study in which the measure was originally published) and/or measures that have documented psychometrics. Measures in this category can be found in Table 1 (n = 140).

Table 1.

Mental Illness Stigma Measures and their Corresponding Mechanisms according to the Mental Illness Stigma Framework

| Year | Authors | Measure or Scale Name | Psychometric Characteristics |

Subscales | MI Stigma Mechanism |

N cites* |

Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1933 | Bogardus | Social Distance Scale | R, WE | D | 213 | Community | |

| 2 | 1987 | Link et al. | R | Community | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 1962 | Cohen & Struening | Opinions about MI | DI, P, R, V, WE | Authoritarianism | S | 13 | Hospital personnel |

| 1963 | Struening & Cohen | Benevolence | S | |||||

| Hygiene | S | |||||||

| Social restrictiveness | S, D | |||||||

| Interpersonal etiology | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4 | 1981 | Taylor & Dear | Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill | DI, P, R, V, WE | Authoritarianism | S, D | 43 | Community/Undergrad |

| Benevolence | S, P | |||||||

| Social restrictiveness | S, D | |||||||

| Community MH ideology | S, P | |||||||

| 5 | 1996 | Wolff et al. | Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill | DI | Fear and exclusion | S, P, D | Community | |

| Social control | S, D | |||||||

| Goodwill | P, D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 6 | 2012 | Hogberg et al | New CAMI-S (Swedish) | DI, P, R | Intention to Interact | S, D | ||

| Fearful and avoidant | P, D | |||||||

| Open-minded and pro-integration | S, D | |||||||

| Community MH ideology | PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 7 | 1985 | Stephan & Stephan | Intergroup anxiety | DI, R, V, WE | P | 2 | Hispanic college students | |

| 2012 | Stathi et al. | Mental illness version | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 8 | 1986 | Link & Cullen | Perceived Dangerousness | R | S | 10 | Community | |

| 1987 | Link et al. | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 9 | 1987 | Kelly et al. | Social Interaction Scale | R, WE | D | 1 | Medical students | |

|

| ||||||||

| 10 | 1987 | Link | Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Scale | R, V, WE | PS, PD | 124 | Community & Psychiatric | |

| 1989 | Link et al. | |||||||

| 1991 | Link et al. | |||||||

| 1997 | Link et al. | |||||||

| 11 | 2007 | Bjorkman et al. | Swedish version | P, R | PWMI | |||

| 12 | 2009 | Moses | Adolescent version | P, R, V | Adolescent MH | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 13 | 1988 | Weller & Grunes | Attitudes toward the Mentally Ill | R | S, P, D | 1 | Nurses | |

|

| ||||||||

| 14 | 1991 | Link et al. | Secrecy Scale | R, WE | Secrecy | AS | 10 | Psychiatric |

| 1997 | Link et al. | |||||||

| 2002 | Link et al. | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 15 | 1992 | Botega et al. | Depression Attitude Questionnaire | DI, P, R, WE | Antidepressant/ psychotherapy | 3 | Doctors | |

| Professional unease | ||||||||

| Inevitable course of depression | S | |||||||

| Identification of depression | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 16 | 1994 | Penn et al. | Penn Affective Reactions | R, WE | P | 9 | Undergraduates | |

| 17 | Penn Characteristics | R | S | 6 | ||||

| 18 | Penn Dangerousness | R | S | 4 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 19 | 1996 | Wolff et al. | Fear and behavioral intentions | Not reported | Fear | P | 1 | Community |

| 20 | 2011 | Svensson et al. | Fear and behavioral intentions | P, R (no support) | Behavioral intentions | D | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 21 | 1997 | Angermeyer and Matschinger | Emotional Reactions | DI, R | Feelings of anxiety | P | 5 | General population |

| Aggressive emotions | P | |||||||

| Prosocial reactions | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 22 | 1997 | Batson et al. | Attitudes toward people with AIDS | R | S, P, D, PD | 1 | College students | |

| 2010 | Kalyanaraman et al. | Adapted for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 23 | 1997 | Link et al. | Link Rejection | R, V, WE | Rejection experiences | ES | 15 | MH patients |

| 24 | 2007 | Björkman et al. | Rejection Experiences-Swedish | P, R | ES | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 25 | 1997 | Raguram, & Weiss | Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue-Stigma Scale | R, WE | PD | 4 | MH | |

| 1997 | Weiss | |||||||

| 1992 | Weiss et al. | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 26 | 1997 | Williams et al. | Everyday discrimination scale | R | D | 1 | Community | |

|

| ||||||||

| 27 | 1998 | Singh et al. | Attitudes To Mental Illness Questionnaire | Not reported | S | 2 | Medical students | |

|

| ||||||||

| 28 | 1999 | Magliano et al. | Questionnaire of Family Opinions | DI, P, R, V | Social restrictions | D | 3 | Family members |

| 2004 | Magliano et al. | Questionnaire on the Opinions about MI | Social distance | D | General public | |||

| Utility of treatments | ||||||||

| Biopsychosocial causes | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 29 | 1999 | Pinel | Stigma Consciousness Scale | DI, P, R, V, WE | AS | 3 | Undergraduates, Gay/Lesbian | |

|

| ||||||||

| 30 | 1999 | Wahl | Consumer experiences of discrimination | V, WE | AS, ES | 16 | MH Consumers | |

| 31 | 2013 | Switaj et al. | Polish version | DI, P, R, V | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 32 | 2000 | Corrigan et al. | Psychiatric Disability Attribution Questionnaire | DI, R | Stability | S | 2 | Community |

| Controllability | S, D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 33 | 2000 | Crisp | Attitudes to MI ("Changing Minds") | Not reported | S | 11 | Community | |

| 34 | 2011 | Svensson et al. | P, R (No support) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 35 | 2000 | Fife & Wright | Social Impact Scale | DI, R, WE | Social rejection | ES | 10 | Consumers (HIV/Cancer) |

| Financial insecurity | Depression, HIV/AIDS, Schizophrenia | |||||||

| Internalized shame | IS, AS | |||||||

| Isolation | IS | |||||||

| 36 | 2007 | Pan et al. | DI, P, R | Unidimensional | AS, ES, IS | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 37 | 2000 | Hirai & Clum | Beliefs Toward MI Scale | DI, P, R, V | Dangerousness | S, P | 1 | Undergraduates |

| Poor interpersonal and social skills | S; AS | |||||||

| Incurability | ||||||||

| 38 | 2013 | Royal & Thompson | DI, P, R, V | Unidimensional | Protestant service goers | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 39 | 2000 | Lauber et al. | Stereotype endorsement scale | Not reported | S | 5 | General population | |

| Social restrictions scale | D | 3 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 40 | 2000 | Ng & Chan | Opinion about Mental Illness in Chinese Community | DI, R | Benevolence | S, D | students | |

| Attitude Scale for MI | Separation | S | ||||||

| Stereotyping | S | |||||||

| Restrictiveness | D | |||||||

| Pessimistic prediction | D, PD | |||||||

| Stigmatization | S, D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 41 | 2001 | Corrigan et al. | Attribution Questionnaire (AQ--27) | DI, R, WE | Personal responsibility | S | 48 | Undergraduate (community college) |

| 2002 | Corrigan et al. | Dangerousness | S | |||||

| 2003 | Corrigan et al | AQ-9 (blame, anger, pity, help, dangerousness, fear, avoidance, segregation, coercion) | Anger | P | ||||

| 2004 | Corrigan et al. | Concern | P | |||||

| 42 | 2012 | Pingani et al. | Italian Version | DI, P, R, V | Fear | P | ||

| 43 | 2012 | Pinto et al. | r-AQ (5 items, unidimensional) | DI, P, R | Helping-avoidance | D | Adolescents | |

| 44 | 2004 | Watson et al. | r-AQ (9 items, for adolescents) | R | Segregation-coercion | D | Adolescents | |

| Fear/dangerousness | S, P | |||||||

| Help/interact | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 45 | 2008 | Brown | Attribution Questionnaire | DI, P, R, V | Responsibility | S | 2 | Undergraduates |

| Forcing treatment | D | |||||||

| Empathy | P | |||||||

| Negative emotions | P | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 46 | 2001 | Harvey | Stigmatization Scale | DI, P, R, V, WE | ES | 2 | Stigmatized group members | |

|

| ||||||||

| 47 | 2001 | Lai et al. | Stigma Questionnaire | DI | Social rejection | AS, ES | 1 | MH Patients |

| 2005 | Chee et al. | Negative Media perceptions | PD | Outpatient MH | ||||

| Shame | IS | |||||||

| Social discrimination | AS | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 48 | 2001 | Struening et al. | Devaluation of Consumers Scale | DI, R | Status reduction | PS | 3 | Caregivers |

| Role restriction | PD | |||||||

| Friendship refusal | PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 49 | 2001 | Read & Harre | Questionnaire on Attitudes towards MH | R | Predicted response items | D | 1 | Undergraduates |

| Semantic differentials | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 50 | 2012 | Dalky | Stigma-Devaluation Scale, Jordan | DI, P, R, V | Status reduction | PS, PD | ||

| Role restriction | PD | |||||||

| Community rejection | PS, PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 51 | 2002 | Christison et al. | Medical Condition Regard Scale | DI, P, R, V, WE | S, P, D | 4 | Medical Students | |

|

| ||||||||

| 52 | 2002 | Thompson et al. | Attitudes toward people with mental illness | Not reported | S | 4 | Community, medical, students, members of Schizophrenia advocacy group | |

|

| ||||||||

| 53 | 2003 | Pinfold et al. | Stigma Questionnaire | Not reported | S | 2 | Students | |

|

| ||||||||

| 54 | 2003 | Angermeyer & Matschinger | Emotional Reactions to MI Scale | DI, R | Fear | P | 8 | General public |

| Pity | P | |||||||

| Anger | P | |||||||

| 55 | Personal Attributes Scale | DI, R | Dangerousness | S | 5 | |||

| Dependency | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 56 | 2003 | Boyd Ritsher et al. | Internalized Stigma of MI Scale | DI, P, R, V, WE | Alienation | IS | 91 | MH outpatients |

| 57 | 2013 | Sibitz et al. | German version | DI, P, R, V | Stereotype endorsement | S, IS | ||

| 58 | 2014 | Boyd et al. | Brief version | DI, P, R, V | Discrimination experiences | ES | ||

| 2014 | Chang et al | DI, P, R, V | Social withdrawal | IS | ||||

| 59 | 2014 | Ociskova et al. | Czech version | DI, P, R, V | Stigma resistance | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 60 | 2003 | Schulze et al. | Questionnaire on Social Distance | R | Stereotypes | S | 8 | Students |

| Social distance | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 61 | 2004 | Austin et al. | Child Stigma Scale | P, R, V | ES, AS | 2 | Parents | |

| 2009 | Moses | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 62 | 2004 | Fortney et al. | Community Stigma | Not reported | Community judgment of drinking | PS, IS | 1 | At-risk drinkers |

| Community judgment about treatment seeking | ||||||||

| Community judgment of specialty treatment services | ||||||||

| Primary care provider judgment | ||||||||

| Specialty provider judgment | ||||||||

| Specialty care lack of privacy | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 63 | 2004 | Angermeyer & Matschinger | Stereotypes of Schizophrenia | DI, R | Dangerousness | S | 6 | General public |

| Attribution of responsibility | S | |||||||

| Creativity | S | |||||||

| Unpredictability/incompetence | S | |||||||

| Poor prognosis | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 64 | 2004 | Griffiths et al. | Depression Stigma Scale | DI, R, WE | Personal stigma | S, D | 56 | Depressed |

| 2008 | Griffiths et al. | Perceived stigma | PS, PD | Community, General Pop, Depressed subset | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 65 | 2004 | Sanders Thompson et al. | Experience of Discrimination Scale | V | ES | 1 | Mental illness | |

|

| ||||||||

| 66 | 2004 | Tanaka et al. | Mental Disorder Prejudice Scale | DI, P, R | Rejection | S, D | General public | |

| Peculiarity | S | |||||||

| Human right alienation | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 67 | 2005 | Baker et al. | Attitudes Toward Acute Mental Health Scale | DI, P, R | Care of control | S | Nursing staff | |

| semantic differentials | S | |||||||

| therapuetic perspectives | S, D | |||||||

| hard to help | S | |||||||

| positive attitudes | S | |||||||

| 68 | 2014 | Gang | Korean version | DI, P, R, V | Professional perspective | 1 | Korean nursing staff | |

| semantic differentials | S | |||||||

| positive attitude | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 69 | 2005 | Haghighat | Standardized Stigmatization Questionnaire | DI, P, R, V | Social self-interest | PD | 2 | Patients and Relatives |

| Psychological self-interest | PD | |||||||

| Evolutionary self-interest | PS, PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 70 | 2005 | Watson et al. | Attitudes Toward Serious MI Scale– | DI, P | Threat | S, P, D, AS† | Adolescent | |

| Adolescent Version | Social construction/concern | S | ||||||

| Wishful thinking | S | |||||||

| Categorical thinking | S, D | |||||||

| Out of control | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 71 | 2005 | Wrigley et al. | Perceived Stigma Scale | Not reported | PS, PD | 5 | Community | |

|

| ||||||||

| 72 | 2005 | Yen et al. | Self-Stigma Assessment Scale, Chinese Version | R | IS | 3 | MH outpatients | |

|

| ||||||||

| 73 | 2005 | Kira et al. | Stigma Consciousness | Not reported | PS, PD, D, AS | 2 | MH clients | |

|

| ||||||||

| 74 | 2006 | Bowers & Allan | Attitudes Toward Personality Disorder Scale | DI, P, R, V | Enjoyment v. loathing | P | 1 | Nurses, prison officers, psychiatric professionals |

| Security v. vulnerability | P | |||||||

| Acceptance v rejection | P | |||||||

| Purpose v. futility | ||||||||

| Exhaustion v. enthusiasm | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 75 | 2006 | Corrigan et al. | Self-Stigma of MI Scale | P, R, V, WE | Stereotype awareness | S | 24 | Psychiatric disabilities |

| 76 | 2007 | Fung et al. | Chinese Version | DI, P, R, V | Stereotype agreement | S | Severe MI | |

| 77 | 2012 | Corrigan et al. | Short Form | P, R, V | Self-concurrence | IS | ||

| Self-esteem decrement | IS | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 78 | 2006 | Kroska & Harkness | Stigmatized Sentiments | V | Evaluation (good v bad) | P | 2 | PWMI |

| Potency (powerful v weak) | ||||||||

| Activity (active v weak) | ||||||||

| 79 | 2006 | Kroska & Harkness | Stigmatized Identity Meanings | V | Evaluation (good v bad) | IS | PWMI | |

| Potency (powerful v weak) | ||||||||

| Activity (active v weak) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 80 | 2006 | Luty et al. | Attitudes Toward Mentally Ill Questionnaire | DI, P, R, V, WE | S, D | 16 | General population | |

|

| ||||||||

| 81 | 2006 | Ucok et al. | Attitudes Toward Schizophrenia | DI | S, D | 2 | General practitioners | |

|

| ||||||||

| 82 | 2006 | Wood & Wahl | IOOV Attitudes and Knowledge | Not reported | Attitudes | D, P | Undergraduates | |

|

| ||||||||

| 83 | 2007 | Day et al. | MI Stigma Scale | DI, R | Anxiety | P | 4 | College Students |

| Relationship disruption | S, D | Community | ||||||

| Hygiene | S | |||||||

| Visibility | S | |||||||

| Treatability | S | |||||||

| Professional efficacy | ||||||||

| Recovery | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 84 | 2007 | Gilbert et al. | Attitudes Toward Mental Health Problem Scale | R | Attitudes toward MH problems | PS, PD | Female university students | |

| External Shame/Stigma awareness | AS† | |||||||

| Internal shame | IS | |||||||

| Reflected Shame 1 | ||||||||

| Reflected Shame 2 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 85 | 2007 | King et al. | The Stigma Scale | DI, P, R | Discrimination | ES | 2 | MH service users |

| Disclosure | AS | |||||||

| Positive aspects | S (1 item) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 86 | 2007 | Luoma et al. | Substance Abuse Perceived Stigma Scale | DI, V | Self-devaluation | IS | 3 | Substance abusers in Tx |

| Fear of enacted stigma | AS | |||||||

| Stigma avoidance | AS | |||||||

| Values disengagement | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 87 | 2007 | Marcks et al. | Vignette Questionnaire | DI, R, V | Social rejection | D | 1 | College students |

| 2013 | Cathey & Witterneck | Modified for OCD | Hiding a drug/alcohol problem | S | ||||

| Psychological/Medical problem | S | |||||||

| Concern | P | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 88 | 2007 | Happell & Gough | Mental Health Nursing Education Survey | DI, R | Negative Stereotypes | S | 1 | Nursing students |

| Preparedness for MH field | ||||||||

| Valuable contribution | ||||||||

| Anxiety surrounding MI | P | |||||||

| Interest in MH nursing as a career | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 89 | 2008 | Collins et al. | Stigma in Psychiatric Illness and Sexuality Among Women | R | Mental illness stigma | ES | 1 | Serious MI |

| Relationship stigma | S | |||||||

| Ethnic stigma | ||||||||

| Perceived attractiveness | ||||||||

| Discrimination | ES | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 90 | 2008 | Eack and Newhill | Attitudes Toward Individuals with Schizophrenia | DI, R | General attitudes | S, D | 1 | Social workers |

| Attitudes about working with individuals with Schizophrenia | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 91 | 2008 | Kanter et al. | Depression Self-Stigma Scale | DI, P, R, V | General self-stigma | ES, AS | 7 | Depressed undergrads and community |

| Secrecy | AS | |||||||

| Public stigma | S, D | |||||||

| Treatment stigma | ||||||||

| Stigmatizing experiences | ES | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 92 | 2009 | Magliano et al. | User Opinions Questionnaire | P, R, V | Affective problems | P | 1 | Schizophrenia patients |

| Social distance | S, D | |||||||

| Usefulness of drug and psychosocial treatments | ||||||||

| Right to be informed | ||||||||

| Recognizability | S, P | |||||||

| Social equality | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 93 | 2009 | Masuda et al. | Stigmatizing Attitudes-Believability | R | S | 4 | Undergraduates | |

|

| ||||||||

| 94 | 2009 | Quinn & Chaudoir | Anticipated Stigma Scale | R | AS | 1 | College students | |

|

| ||||||||

| 95 | 2010 | Aromaa et al. | Attitudes towards people with mental disorders | DI, P, R | Depression is a matter of will | S | 2 | General population |

| Mental problems have negative consequences | S | |||||||

| One should be careful with antidepressants | ||||||||

| You never recover from mental problems | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 96 | 2010 | Barney et al. | Self-Stigma of Depression Scale | DI, P, R, V | Shame | IS, AS† | Undergraduate, Internet, Depressed, General pop Depressed | |

| Self-blame | IS, AS† | |||||||

| Social inadequacy | IS, AS† | |||||||

| Help-seeking inhibition | IS, AS | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 97 | 2010 | Bell et al. | Stereotypic Beliefs | Not reported | S | 1 | Pharmacy Students | |

|

| ||||||||

| 98 | 2010 | Evans-Lacko et al. | Mental Health Knowledge Schedule | P, R, V, WE | S | 16 | General public | |

|

| ||||||||

| 99 | 2010 | Fresan et al. | Public Conception of Aggressiveness Questionnaire | DI, P, R | Aggressiveness | S | General public | |

| Mental disease | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 100 | 2010 | Gabriel & Violato | Attitudes towards depression and its treatments | DI, P, R, V | Acceptance of treatment | Depressed | ||

| Perceived stigma and shame | IS, ES | |||||||

| Negative attitudes toward antidepressants | ES | |||||||

| Self-stigma | S, ES | |||||||

| Preference for psychotherapy | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 101 | 2010 | Karidi et al. | Self-Stigmatization Questionnaire | Not reported | ES, AS, IS | 1 | Schizophrenia outpatients | |

|

| ||||||||

| 102 | 2010 | Kassam et al. | MI: Clinicians' Attitudes Scale | DI, P, R, V | S, D, AS† | 5 | Medical students | |

| 103 | 2013 | Gabbidon et al. | MI: Clinicians' Attitudes Scale (healthcare professions version) | DI, R, V | Views of health/social care field and MI | D | Healthcare Professionals | |

| Knowledge of MI | S | |||||||

| Disclosure | AS† | |||||||

| Distinguishing mental and physical health | ||||||||

| Patient care for people with MI | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 104 | 2010 | Kellison et al. | ADHD Stigma Questionnaire | DI, P, R, V | Disclosure concerns | 3 | Community adolescents | |

| Negative self-image | S; IS | |||||||

| Concern with public attitudes | PS, ES, AS | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 105 | 2010 | Kobau et al. | Generic Scale for Public Health Surveillance of MI Associated Stigma (HealthStyles Survey 2006) | DI, P, R, V | Negative stereotypes | S | General public | |

| Recovery and outcomes | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 106 | 2010 | Luoma et al. | Perceived Stigma of Addiction Scale | DI, P, R, V | PS, PD | Substance abuse tx | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 107 | 2010 | Mak & Cheung | Self-Stigma Scale–Short Form | DI, P, R, V | Affective | IS | 2 | MH consumers |

| Behavioral | IS | Immigrants | ||||||

| Cognitive | IS | Sexual minorities | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 108 | 2011 | Brown | Social Distance Scale for Substance Users | P, R, V | D | undergraduates | ||

| 109 | Dangerous Scale for Substance Users | P, R, V (no support) | S | |||||

| 110 | Affect Scale for Substance Users | P, R, V | P | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 111 | 2011 | Clayfield et al. | Mental Health Attitude Survey for police | DI, P, R | Positive attitudes toward EDPs | S,D | Police | |

| Negative attitudes toward community responsibility for EDPs | D | |||||||

| Not adequately prepared to deal with EDPs | ||||||||

| Positive attitudes toward EDPs living in the community | P,D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 112 | 2011 | Evans-Lacko et al. | Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale | P, R, V, WE | Reported behavior | D | 17 | General population |

| 113 | 2014 | Yamaguchi et al. | Japanese version | DI, P, R, V | Intended behavior | D | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 114 | 2011 | Griffiths et al. | Generalized Anxiety Stigma Scale | DI, P, R, V | Personal stigma | S, D | 3 | General population |

| Perceived stigma | PS, PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 115 | 2011 | Palamar | Drug Use Stigmatization Scale | DI, P, R, V | Stigma of drug users scale | S | 3 | Adults |

| Drug use stigmatization scale | PS, PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 116 | 2011 | Scheerder | Attitudes Toward Depression | Not reported | S | 2 | Community and Health Professionals | |

|

| ||||||||

| 117 | 2011 | Wahl et al. | Knowledge and Attitudes about MI | R | Knowledge | S | 1 | Adolescents |

| Attitudes | S, P, D, AS† | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 118 | 2012 | Birchwood et al. | Personal Beliefs about Illness Questionnaire-Revised | DI, P, R, V | Entrapment | IS | 6 | MH Patients |

| 1993 | Birchwood et al. | Personal Beliefs about Illness Questionnaire | Loss | IS | MH Patients | |||

| Social marginalization | IS | |||||||

| Shame | IS | |||||||

| Control | IS | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 119 | 2012 | Fuermaier et al. | Adult ADHD Stigma Scale | DI, P, R | Reliability and social functioning | S, D | 1 | Undergraduates, community |

| Malingering and misuse of medication | S | |||||||

| Ability to take responsibility | S, D | |||||||

| Norm-violating and externalizing behavior | S | |||||||

| Consequences of diagnostic disclosure | S | |||||||

| Etiology | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 120 | 2012 | Kassam et al. | Opening Minds Scale for Health Care Providers | DI, P, R, V | Attitudes of healthcare providers | S, P | 4 | Healthcare providers |

| Attitudes toward disclosure | AS | |||||||

| Attitudes of healthcare providers toward PWMI | ||||||||

| Disclosure/help-seeking | ||||||||

| Social distance | D | |||||||

| 121 | 2014 | Modgill et al. | 15-item version | DI, P, R, V | Attitudes | S, P | Healthcare providers | |

| Disclosure/help-seeking | AS | |||||||

| Social distance | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 122 | 2012 | Madianos et al. | Public Attitudes Toward MI Greece | DI, P, R, V | Stereotyping | S | General population | |

| Optimism | S | |||||||

| Coping | ||||||||

| Understanding | PS, PD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 123 | 2012 | Scocco et al. | Stigma of Suicide Attempt | DI, P, R | Supportive/respectful/caring attitudes | D | Gen Pop, MH patients, attempters, SO who lost someone to suicide | |

| Stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs | S, D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 124 | 2012 | Siu et al. | Attitudes Toward Mental Disorders | Not reported | S, P, D | 2 | Secondary school, community (elderly,public and private housing) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 125 | 2012 | van der Heijden | Nurses’ Perceptions of MH Care | DI, P, R, V | Student s' views on psychiatric patients | S, PS | students | |

| Students' views on a career in mental health care | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 126 | 2013 | Batterham et al. | Stigma of Suicide Scale | DI, P, R, V | Stigma | S | 4 | University student and staff (community) |

| 127 | Short Form | DI, P, R, V | Isolation/depression | S | ||||

| Glorification/normalization | S | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 128 | 2013 | Brohan et al. | Discrimination and Stigma Scale | DI, P, R, V, WE | Unfair treatment | ES | 19 | Community MH service users |

| Stopping self | AS | |||||||

| Overcoming stigma | ||||||||

| Positive treatment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 129 | 2013 | Gabbidon et al. | Questionnaire on Anticipated Discrimination | P, R, V | AS | 1 | Community MH service users | |

|

| ||||||||

| 130 | 2013 | Glass et al. | Perceived Alcohol Stigma Scale | DI, P, V | PS, PD | General population | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 131 | 2013 | Hirsch | Biases Toward Children with Psychological and Behavioral Problems Scale | DI, P, R,V | S | Professionals and students | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 132 | 2013 | Ilic et al. | Multifaceted Stigma Experiences Scale | DI, P, R, V | Hostile discrimination | ES | 1 | MH Tx seekers |

| Benevolent discrimination | ES | |||||||

| Taboo | ES | |||||||

| Denial | ES | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 133 | 2013 | Luoma et al. | Substance Abuse Self-Stigma Scale | DI, P, R, V | Self-devaluation | IS | Substance abusers | |

| Fear of enacted stigma | AS | |||||||

| Stigma avoidance | AS, IS | |||||||

| Values disengagement | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 134 | 2013 | Michaels & Corrigan | Knowledge Test | P, R, V | S | 2 | Undergraduates, MH Providers, MH consumers | |

|

| ||||||||

| 135 | 2013 | Mileva et al. | Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences | P, R | Stigma experiences scale | AS, IS, ES | 7 | MH patients |

| 2005 | Stuart et al. | Stigma impact scale | ES | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 136 | 2013 | Segal et al. | Attitudes Toward Persons With MI Scale | DI, R | Rejection-- intimate contact | D | 1 | Community mental health clients |

| Rejection-- competence/trustworthiness | S, D | |||||||

| Rejection--severity of illness | S, D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 137 | 2014 | Heflinger et al. | Attitudes about Child Mental Health Questionnaire | DI, P, R, V | Child dangerousness/incompetence | S | Community | |

| General stereotypes | S | |||||||

| Community devaluation/discrimination | PS, PD | |||||||

| Personal attitudes | P, D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 138 | 2014 | Karidi et al | Stigma Inventory for Mental Illness | DI, P, R, V | Perceptions of Social Stigma | AS | Schizophrenia outpatients | |

| Self-efficacy | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 139 | 2014 | Mak et al. | Stigma and Acceptance Scale | DI, R | Public stigma | S, P, D | 1 | Community |

| Stigma acceptance | D | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 140 | 2014 | Vogt et al. | Endorsed and Anticipated Stigma Inventory | DI, P, R, V | Negative beliefs about MH treatment | 1 | Veterans | |

| Negative beliefs about MH treatment seeking | S | |||||||

| Negative beliefs about mental illness | S | |||||||

| Concerns about stigma-- family/friends | AS† | |||||||

| Concerns about stigma-- workplace | AS† | |||||||

Notes.

Number of citations in the current review; MI = mental illness; MH = mental health; For psychometric evaluation: DI = dimensionality examined, R = at least one form of reliability reported (e.g., internal consistency, test-retest), P = published psychometric paper, V = at least one form of validity examined (e.g., construct, convergent, divergent, concurrent, discriminant, predictive),WE = well-established measure in the literature with 10+ citations in the past ten years. For stigma mechanisms: D = discrimination, S = stereotypes, P = prejudice, PS = perceived stereotypes, PD = perceived discrimination, AS= anticipated stigma, AS

AS† indicates an anticipated stigma measure that can be administered to the general population, IS = internalized stigma, ES = experienced stigma

The second category consisted of measures described as being specifically created for the study, measures where no citation information was provided, measures that were created by pulling items from multiple measures, and newly developed measures of stigma that had not yet been cited or psychometrically validated in other studies. We refer to this set of measures as “study-created measures” and although they are not included in Table 1, we classified the stigma mechanisms assessed in each measure and summarize the findings. In total, we identified 304 study-created measures (reference list of articles containing study-created measures is available from the first author).

Not included in either category of measures are national or international “indicator” measures of stigma (n = 8). These measures were typically one or two items and were designed to be easily administered in population-level studies to gauge overall levels of stigma in a particular country or context (e.g., General Social Survey, National Survey Study-Children, National Comorbidity Study). A list and description of these measures is available from the first author.

Classifying Measures

We attempted to obtain a copy of each measure included in Table 1. We were not able to obtain original copies of two measures that were not published in English (Sibitz et al., 2013; Zeng et al., 2009). If the article in which the original measure was cited provided the items or enough detail to classify the type of stigma measured, we kept it in Table 1. Our final list included 140 measures of stigma, comprising 330 scales or subscales. For each measure, we recorded the psychometric properties described in the paper and the number of times it was cited in our search. We examined the items included in the measure and classified the stigma mechanism(s) the measure captured at the factor or subscale level. For some measures, there were multiple versions or adaptations available (e.g., validated in a different language or for a different population than the original measure). If an alternative version of a measure had a published psychometric paper available, we counted it as a separate measure when determining the total number of measures we identified and when examining the psychometric characteristics available for the measures. However, in order to avoid over-inflating the totals for the stigma mechanisms contained in the measures, we grouped multiple versions of measures together and only classified the stigma mechanisms once for all versions of the measure (assuming they shared the same items and factor structure). Operational definitions and example items for each stigma mechanism are included in Supplemental File 2.

Psychometric Evaluation of Measures

Information regarding the availability of psychometric properties of each measure is included in Table 1 and a more detailed evaluation of the quality of the evidence for these measurement properties is included in Supplemental File 3. In Table 1, measures were given an “R” if details about at least one form of reliability (e.g., internal consistency, test-retest) were available and a “V” if details about at least one form of validity (e.g., construct, convergent, predictive, concurrent) were available. Measures were given a “D” if the underlying dimensionality (i.e., factor structure) of the measure was reported. We gave a rating of “P” if there was a published paper specifically describing the development of the measure. A measure was considered well-established in the literature and given a rating of “WE” if it had been cited at least 10 times. For measures that were developed before 2004, we checked PsycInfo to see if it had been cited more than 10 times.

In Supplemental File 3, we evaluated measures using the quality criteria developed by Terwee et al. (2007). As part of the COSMIN initiative (Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments), Terwee, Mokkink, and colleagues developed a set of standard measurement quality criteria in order to facilitate comparisons of health outcomes questionnaires (Mokkink et al., 2010a, 2010b; Terwee et al., 2007). Terwee et al. provide guidelines for assessing the quality of evidence for content validity, internal consistency, criterion validity, construct validity, reproducibility, responsiveness, floor and ceiling effects, and interpretability. For each measurement property, measures are given a “+”, “−,” “indeterminate,” or “no information available” rating. A full description of each rating is provided in Supplemental File 3. Within the stigma literature, the COSMIN criteria have been used to evaluate measures of internalized stigma (Stevelink, Wu, Voorend, & van Brekel, 2012) and measures of experiences of mental illness stigma (Brohan et al., 2010). In the present study, we followed the same procedures as Brohan et al. (2010) and evaluated measures based on a subset of the COSMIN criteria most relevant to measures of stigma: content validity, internal consistency, construct validity, test-retest reliability, and floor-ceiling effects.

Results

Overview of mental illness stigma measures

Figure 2 presents the number of stigma measures that have been developed in the past decade, broken down by whether the measure has been psychometrically validated for its intended use. The findings are striking. On average, 36 measures of stigma have been developed per year since 2004. On average since 2004, measures without established psychometrics have appeared in the literature about six times as often as new validated measures. Measures have been developed to assess every stigma mechanism, and for a wide range of mental illnesses, including depression (e.g., Griffiths et al., 2004; Griffiths et al., 2008), alcohol and substance use disorders (e.g., Brown, 2011; Glass, Kristjansson, & Bucholz, 2013; Luoma, O’Hair, Kohlenberg, Hayes, & Fletcher, 2010; Luoma et al., 2007; Luoma et al., 2013), schizophrenia (e.g., Ucok et al., 2006), suicide (e.g., Batterham, Calear, & Christensen, 2013), suicide attempts (e.g., Scocco, Castriotta, Toffol, & Preti, 2012), generalized anxiety disorder (e.g., Griffiths, Batterham, Barney, & Parsons, 2011), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (e.g., Fuermaier et al., 2012).

Overall Psychometric Summary of Mental Illness Measures

The fifth column of Table 1 contains a description of the psychometric characteristics of each measure. In total, 55.0% (n = 77) of measures had a published psychometric paper available (i.e., a paper describing the development of the measure and its psychometric characteristics) and 17.1% (n = 24) had been cited at least ten times. Information regarding the dimensionality of the measure was described for 58.6% (n = 82), and 48.6% (n = 68) had information about at least one form of validity. The majority of scales (n = 115, 82.1%) had information regarding the reliability of the measure. Fourteen measures did not report any psychometric properties and three measures were found to have no psychometric support.

Of the measures with a psychometric paper available, 61.0% (n = 47) included an examination of at least one form each of reliability, validity, and dimensionality. A total of eight of those measures have been cited at least 10 times in the past decade (although we acknowledge that the 14 measures published since 2012 that have all three psychometric characteristics available may not have been in the literature long enough to be cited 10 times). While there were at least two psychometric characteristics available for most measures in Table 1 (n = 91, 65.0%), 34 measures (24.3%) had only one type of psychometric data available.

Mental Illness Stigma Mechanisms

Before examining the measures associated with each of the stigma mechanisms in the MISF, we began by looking at the number of measures that were associated with the perspective of the stigmatizer versus those associated with the perspective of the stigmatized. Of all the measures we identified, 39 (28%) addressed the perspective of the stigmatized and 100 (72%) were developed from the perspective of the stigmatizer. In the broader literature search, 327 articles (34.2%) were focused on the perspective of the stigmatized (i.e., PWMI).

Stereotypes

Stereotypes were the most widely measured stigma mechanism in our review, with 418 of the 957 articles (43.5%) containing a measure of the extent to which people endorse stereotypical beliefs about mental illness. Among the measures we identified, stereotypes were captured in 128 different scales or subscales. Of those 128 different scales or subscales, 63.3% (n = 81) solely measured stereotypes. The remaining scales or subscales (n = 47) included items assessing at least one other stigma mechanism, with discrimination being the most common mechanism to co-occur within the scale (n = 35).

In terms of their psychometric properties, 28 measures reported information on reliability, validity and dimensionality, and another 29 measures reported only two of those three characteristics. Fifteen measures only reported information on one psychometric characteristic, and eight measures did not provide any psychometric information. In total, 45 measures had a psychometric paper available, and 9 measures were classified as well-established.

The most widely used measure containing stereotypes was the ISMI scale (Boyd Ritsher et al., 2003; n = 89), followed by the Depression Stigma Scale (DSS; Griffiths et al., 2004; 2008; n = 56), the Attribution Questionnaire (AQ; Corrigan, Green, Lundin, Kubiak, & Penn, 2001; n = 48), and the Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill Scale (CAMI; Taylor & Dear, 1981; n = 43). Both the ISMI and CAMI are well-validated measures, with psychometric information available regarding their reliability, validity and dimensionality (although only the ISMI has a published psychometric paper). Reliability and dimensionality have been examined with the AQ and DSS.

The most common stereotypes addressed in the stereotype measures were that PWMI are weak, dangerous, unpredictable, violent, and that they are responsible for their condition. Some measures focus on the stereotypes associated with specific disorders. For example, the “personal stigma” subscale of the DSS asks people the extent to which they think that people with depression can snap out of it. Although the ADHD stigma scale (Kellison, Bussing, Bell & Garvan, 2010) focuses on ADHD, the items were adapted from an HIV stigma scale and could be adapted for other mental illnesses. The “personal stigma” subscale of the Generalised Anxiety Stigma Scale (Griffiths et al., 2011) also addresses stereotypes that could be applied to other mental disorders. Thus, although numerous measures have focused on a specific disorder, for the most part, the stereotypes included could apply to any disorder.

Prejudice

Prejudice was the least measured stigma mechanism, measured in 141 articles (14.7%), and captured in 42 scales or subscales. Twenty measures or subscales also included items assessing other stigma mechanisms, with stereotypes being the most common co-occurring mechanism. The most cited measures of prejudice were the AQ and the CAMI. A total of ten measures had information related to all three psychometric characteristics, 13 measures presented two psychometric characteristics, and nine measures reported just one. Two measures did not provide any psychometric information. Three measures were well-established, and 16 had a psychometric paper.

Fear and anger appear to be the most common forms of prejudice captured in the measures. The AQ contains a fear subscale, and the CAMI includes items that address fear (e.g., It is frightening to think of people with mental problems living in residential neighborhoods) and lack of sympathy (e.g., The mentally ill do not deserve our sympathy).

Discrimination

Discrimination was the second most widely measured stigma mechanism in our review, with 43.1% (n = 412) of articles containing a measure of discrimination. Among the measures we identified, discrimination was captured in 69 different scales or subscales, and was the sole stigma mechanism measured in 29 (42.0%) of the scales or subscales. Stereotypes were the most common co-occurring stigma mechanism.

In terms of psychometric characteristics of the measures, eight measures were rated as well-established and 15 measures had information available regarding reliability, validity and dimensionality. A total of 19 measures reported two psychometric characteristics, 13 measures reported only one, and four measures did not provide any psychometric information.

The most cited measure of discrimination was also the most cited overall—social distance. Social distance was measured in 213 of 957 articles (22.3%). The original social distance scale (SDS) was a type of Guttman scale developed by Bogardus (1933) and contains seven equidistant items related to people’s willingness to engage in social contact with people from other social groups. Participants are asked to read each statement and indicate whether they would be willing to engage in that type of social relationship (yes/no). However, many researchers use modified versions of the SDS or created their own. For example, Link et al. (1987) modified the Bogardus SDS so that the seven items were no longer necessarily equidistant, and participants respond to each of seven items using a 0 to 3 Likert scale. Others tie the social distance scale to a vignette describing someone with mental illness (e.g., Boyd, Katz. Link & Phelan, 2010; Yap, Reavley, & Jorm, 2013). Given the variability in how social distance is measured, it is challenging to assess the psychometric characteristics of the measure. However, reliability information is available for both the Bogardus and Link versions of the scales.

Other concepts that were captured in the discrimination measures include avoidance, social restrictiveness, and willingness to help. For example, the AQ contains subscales that assess willingness to help someone with mental illness as well as the extent to which people agree that PWMI should be segregated from the general population (i.e., put in mental hospitals).

Experienced Stigma

Experienced stigma was captured in 17.2% (n =165) of the articles and we identified 27 scales or subscales measuring experienced stigma. The majority of measures exclusively focused on experienced stigma (63.0%). However, ten subscales also captured other mechanisms, with anticipated or internalized stigma co-occurring most often. In terms of psychometrics, nine measures reported all three psychometric characteristics, four measures reported two forms, six reported only one form, and one did not present any. Six measures were well-established, and 12 measures had psychometric papers available.

The most cited measure of experienced stigma was the ISMI, which includes an experienced stigma subscale that assesses day-to-day discrimination experienced by PWMI. The next most cited measures of experienced stigma were the CESQ, Link et al.’s (1997) Rejection Experiences Scale, and Fife & Wright’s (2000) Social Impact Scale (SIS), all of which include items assessing both day-to-day discrimination (e.g., being avoided), as well as more acute forms of discrimination (e.g., being denied a job).

Anticipated Stigma

In total, 10.0% (n = 96) of articles cite measures that assesses anticipated stigma, and we identified 37 anticipated stigma scales or subscales. Fifteen measures provided information regarding reliability, validity, and dimensionality, and twelve of those also included a published psychometric paper. Six measures presented two forms of psychometrics, eight presented only one form, and two did not present any psychometric information.

Interestingly, 19 of the 37 scales or subscales (51.4%) that assessed anticipated stigma also include items that address at least one other stigma mechanism, with internalized stigma and experienced stigma co-occurring most often. Additionally, the most cited measures of anticipated stigma are primarily measures of experienced stigma that include items that also assess anticipated stigma: the SIS (n = 10) and CESQ (n = 16). One recently developed measure, the Questionnaire on Anticipated Discrimination (QUAD; Gabbidon et al., 2013), is entirely focused on anticipated stigma and appears to be a psychometrically valid and promising measure.

In our framework, anticipated stigma is one of the mechanisms specific to PWMI. Therefore, one needs to have a mental illness in order to anticipate stigma related to mental illness. However, 27.0% (n = 10) scales or subscales identified as assessing anticipated stigma were designed to be completed by people who may or may not have mental illness. In some of these measures, individuals are asked to report how they think they would feel (e.g., If I had a mental illness, I would feel bad about myself) if they were to have a mental illness. For PWMI, these items may be capturing aspects of anticipated or internalized stigma (or both). For people who do not have mental illness, it is unclear what mechanism is being tapped.

Some of these measures assess how they think others would react to them if they had a mental illness (e.g., “If I had a mental illness, friends and family would think I am weak”). For PWMI, these measures are likely tapping anticipated stigma because they are asking to what extent people expect to be the target of stereotyping and discrimination. For people who do not have mental illness, these measures are likely tapping perceived stigma—how do people think others will react to PWMI.

Internalized Stigma

Of articles in the broader search, 150 (15.7%) include a measure of internalized stigma. A total of 29 scales or subscales assess internalized stigma. More than one-third (34.5%) of internalized stigma measures also included items that address other stigma mechanisms (n = 10), with anticipated stigma co-occurring the most often.

In terms of the psychometric characteristics, eight measures provided information on reliability, validity, and dimensionality, and all of them were accompanied by a published psychometric evaluation. However, only three measures were categorized as well-established, and only one of those three had a published psychometric paper (ISMI). Four measures provided two psychometric characteristics, five provided only one, and two measures did not have any psychometric information provided.