Abstract

Pakistan is one of 3 countries where transmission of indigenous wild poliovirus (WPV) has never been interrupted. Numbers of confirmed polio cases have declined by >90% from preeradication levels, although outbreaks occurred during 2008–2013. During 2012 and 2013, 58 and 93 WPV cases, respectively, were reported, almost all of which were due to WPV type 1. Of the 151 WPV cases reported during 2012–2013, 123 (81%) occurred in the conflict-affected Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and in security-compromised Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. WPV type 3 was isolated from only 3 persons with polio in a single district in 2012. During August 2012–December 2013, 62 circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 cases were detected, including 40 cases (65%) identified in the FATA during 2013. Approximately 350 000 children in certain districts of the FATA have not received polio vaccine during supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) conducted since mid-2012, because local authorities have banned polio vaccination. In other areas of Pakistan, SIAs have been compromised by attacks targeting polio workers, which started in mid-2012. Further efforts to reach children in conflict-affected and security-compromised areas will be necessary to prevent reintroduction of WPV into other areas of Pakistan and other parts of the world.

Keywords: polio, disease eradication, epidemiology, surveillance, Pakistan

Pakistan is one of 3 countries where transmission of indigenous wild poliovirus (WPV) has never been interrupted [1]. The most populous member country of the World Health Organization (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), Pakistan has an estimated population of 173.1 million, including 21.3 million children aged <5 years and 61.4 million children aged <15 years (2010 estimates) [2]. Administratively, Pakistan is divided into 4 provinces (Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa [KP], Punjab, and Sindh), the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the Islamabad Capital Territory, and 2 administrative areas (Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan). Pakistan is one of the less developed countries in the EMR, with a gross domestic product per capita of $1184 in 2012 and an adult literacy rate of 55% [3].

In 1988, in accordance with the resolution of the World Health Assembly, the Regional Committee of the WHO EMR resolved to eradicate polio from the region by 2000 [1, 4]. The key strategies adopted for polio eradication included (1) achieving and maintaining high coverage with ≥3 doses of oral polio vaccine (OPV3); (2) implementing supplementary immunization activities (SIAs; defined as mass campaigns conducted for a brief period [days to weeks], in parts of or the entire country, in which 1 dose of OPV is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of vaccination history), to rapidly interrupt poliovirus transmission; and(3) developing sensitive systems of epidemiologic and laboratory surveillance, using standard WHO definitions [4]. Pakistan initiated eradication activities in 1994, when it conducted its first SIAs for polio, and began acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in 1995 [4–6]. During 1994–2013, Pakistan made substantial progress toward polio eradication, reducing the average annual number of cases by nearly 95%, compared with the prevaccine era; eliminating transmission of WPV type 2 (WPV2) and WPV3, with the last cases confirmed in 1997 and 2012, respectively; and decreasing the genetic diversity of WPV1 isolates circulating in Pakistan. However, a resurgence of cases since 2008 and an explosive outbreak in conflict-affected and insecure areas of the FATA and KP during 2012–2013 threaten the achievement of recent eradication efforts. In this article, we summarize the history of polio eradication activities in Pakistan from 1994 to 2013, describe the recent progress made through implementation of the strategies of the national emergency action plan, and discuss the threat to successful polio eradication in Pakistan and the world caused by ongoing conflict in tribal areas and insecurity in other areas of the country.

BACKGROUND

Routine Immunization

The Expanded Program on Immunization began in Pakistan in 1978, with the immunization of infants against 6 childhood diseases, including poliomyelitis, using a 3-dose OPV schedule involving vaccination at 6, 10, and 14 weeks of age. A birth dose of OPV was added to the schedule in 1994 as part of the polio eradication initiative in Pakistan. Immunization services are provided at government hospitals, health centers, and outreach clinics and by pediatricians and other private practitioners, primarily in urban areas.

SIAs

Polio eradication in Pakistan began in 1994 with SIAs intended to boost population immunity rapidly and interrupt poliovirus transmission quickly. During 1994–1999, 2 rounds of nationwide SIAs or National Immunization Days (NIDs) were conducted each year, with >20 million children vaccinated annually (Table 1). During 1994–1995, NIDs were conducted in Pakistan during the season when the risk of poliovirus transmission was high, to coordinate with NIDs in neighboring countries; subsequent NIDs were conducted during the season when the risk of transmission was low (ie, December–February) [5]. During 1998–1999, Pakistan implemented subnational immunization days (SNIDs) in districts bordering Afghanistan and Iran to coincide with NIDs in those countries (Table 1) [5, 6].

Table 1.

Supplementary Immunization Activities (SIAs) at National and Provincial Levels and Postcampaign Assessments—Pakistan, 1994–2013

| Year | National Immunization Days, No. | Subnational Immunization Days, No. | Short-Interval Additional Dose Campaigns,a No. | Other Campaigns (Outbreak Response), No. | Type(s) of OPV Used | Postcampaign Assessment(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 2 | … | … | … | T | … |

| 1995 | 2 | … | … | … | T | … |

| 1996 | 2 | … | … | … | T | … |

| 1997 | 2 | … | … | … | T | National survey (87%) |

| 1998 | 2 | 4 | … | 4 | T | … |

| 1999 | 2 | 2 | … | … | T | District surveys (72%–99%) |

| 2000 | 4 | 3 | … | … | T | … |

| 2001 | 5 | 3 | … | … | T | … |

| 2002 | 4 | 4 | … | … | T | IM |

| 2003 | 4 | 4 | … | … | T | IM |

| 2004 | 7 | 1 | … | … | T | IM |

| 2005 | 7 | 1 | … | … | T, M1 | IM |

| 2006 | 6 | 2 | … | 4 | T, M1 | IM |

| 2007 | 4 | 7 | … | NA | T, M1, M3 | IM |

| 2008 | 5 | 6 | … | 3 | T, M1, M3 | IM-FM |

| 2009 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | T, M1, M3 | IM-FM |

| 2010 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 11 | T, M1, M3, B | IM-FM |

| 2011 | 4 | 6 | NA | NA | T, B | IM-FM, LQAS |

| 2012 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | T, B | IM-FM, LQAS |

| 2013 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 13 | T, B | IM-FM, LQAS |

SIAs are defined as mass campaigns conducted for a brief period (days to weeks) in which 1 dose of oral poliovirus vaccine is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of vaccination history. Campaigns can be conducted nationally or in portions of the country.

Abbreviations: B, bivalent OPV, types 1 and 3; IM, independent monitoring through rapid convenience surveys, using parental recall of children’s SIA dose(s) received; IM-FM, independent monitoring with finger marking, through rapid convenience surveys, looking for indelible ink on children’s fingernails as objective marker of receipt of SIA dose; LQAS, use of lot-quality assurance surveys to determine whether the number of children vaccinated in an area (lot) was greater than or equal to a predefined acceptable level; M1, monovalent OPV type 1; M3, monovalent OPV type 3; NA, not available; OPV, oral polio vaccine; T, trivalent OPV.

Short-interval additional-dose campaigns are used during negotiated periods of nonviolence in otherwise inaccessible areas to administer a second dose of monovalent oral polio vaccine or bivalent oral polio vaccine within 1–2 weeks of the previous dose.

Beginning in 2000, the number and intensity of SIAs increased with use of a house-to-house vaccination strategy; at least 7 rounds of large-scale campaigns (NIDs or SNIDs) annually; numerous smaller-scale campaigns, including short-interval additional dose (SIAD) campaigns, which are used during negotiated periods of nonviolence in otherwise inaccessible areas to administer a second dose of monovalent OPV or bivalent OPV (bOPV) within 1–2 weeks of the previous dose; use of additional staff for campaign planning and implementation; and improved monitoring and postcampaign assessment (Table 1) [7–10]. Areas targeted for SNIDs were those in which various factors (eg, surveillance results, genetic sequencing of WPVs, supplementary or routine immunization coverage, and population dynamics) indicated a high risk for continuing poliovirus transmission, especially in the security-compromised areas of KP and the FATA and a transmission zone extending from southern Punjab and Sindh (including Karachi), through Balochistan, and into the southern region of Afghanistan. Since 1998, SIAs in Pakistan and Afghanistan have generally been synchronized to ensure simultaneous, comprehensive coverage of border areas and children in transit.

Trivalent OPV (tOPV) was used in SIAs from 1994 to 2004 [4–10]. In 2005 and 2007, monovalent OPV types 1 (mOPV1) and 3 (mOPV3), respectively, were introduced in Pakistan and used in various combinations with tOPV in campaigns during 2005–2010, depending on the epidemiological situation of the target areas and populations for each campaign (Table 1) [11–15]. With the introduction of bOPV (containing types 1 and 3) in 2010, use of mOPV1 and mOPV3 was discontinued, and tOPV and bOPV were used for SIAs during 2010–2013 [16–18].

Since at least 2005, polio teams have often had difficulty gaining access to children and effectively implementing SIAs in remote areas and known high-risk, security-compromised areas along the border with Afghanistan, primarily in KP and the FATA, that are affected by conflict [11–13]. Because of deteriorating regional security, the number of children aged <5 years living in inaccessible areas (ie, areas considered by the WHO and the local government to be too dangerous for conducting an SIA) increased during 2008–2013 [14–18].

Poliovirus Surveillance

AFP surveillance began in Pakistan in 1995. Through this system, AFP cases in all children aged <15 years and suspected cases of poliomyelitis in persons of any age were reported and investigated as possible poliomyelitis. During 1995–1997, provincial staff were trained in AFP surveillance, and surveillance assessments were conducted in many districts. AFP surveillance became fully functional in 1998 [5, 6]. Beginning in 1999 and early 2000, provincial surveillance officers were hired by the WHO to provide continuous training and technical assistance to staff in all provinces and areas [7]. During 1999–2013, international health professionals were deployed through the Stop Transmission of Polio (STOP) program on 3–5-month assignments to assist with polio eradication activities and to improve surveillance quality. Since 2010, specially trained Pakistani public health officers have provided surveil-lance system strengthening through the national STOP (N-STOP) program.

During 1994–1999, the WHO clinical classification scheme for reporting confirmed polio cases was used in Pakistan (AFP cases were classified as confirmed polio cases if WPV was isolated from 1 or more stool specimens or the case patients had residual paralysis at 60 days, died, or were lost to follow-up) [6]. In January 2000, the current global classification scheme was initiated: AFP cases with WPV identified were classified as confirmed polio cases, and those without adequate stool specimens but with signs and symptoms consistent with polio were classified as compatible with polio by a review committee of medical experts. In 2004, to increase the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system, the collection of stool samples was expanded to include the direct contacts of AFP cases whose stool specimens were not properly collected, stored, or shipped to the laboratory [10].

In 2009, to supplement AFP surveillance, Pakistan initiated periodic sewage sample collection in Lahore, Punjab province, and Karachi, Sindh province, to test for polioviruses [15]. During 2010–2011, sewage sample collection was expanded to 18 sites in 6 cities, with further expansion to 23 sites in 11 cities during 2012–2103 (current locations include Karachi [3 towns], Hyderabad, and Sukkur in Sindh; Lahore, Rawalpindi, Multan, and Faisalabad in Punjab; Peshawar in KP; and Quetta in Balochistan) [16–18].

METHODS

Routine Immunization

Routine immunization coverage with OPV3 was calculated annually by dividing the total number of doses administered to children in the targeted age group by the estimated population of children in that age group, based on the most recent population data, and findings were reported to the WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF; official coverage). Additionally, the WHO and UNICEF estimated coverage of OPV3 annually, using reported coverage of OPV3 and survey results, including the 2004 National Coverage Survey [19]. Surveillance data from non–polio-associated AFP (NPAFP) cases were also used to provide a proxy measure for routine OPV3 coverage (vaccination histories of children aged 6–23 months with AFP who do not test positive for WPV are used to estimate OPV coverage of the overall target population and to corroborate national reported routine vaccination coverage estimates) [15–18].

SIAs

Reported coverage during SIAs was calculated by dividing the total number of OPV doses administered to children in the targeted age group by the estimated population of children in that group. Since 2002, the quality of SIAs was monitored by independent groups, usually private survey companies or university teams, that measured process indicators during campaigns and conducted immediate postcampaign assessments (Table 1) [8–10]. In 2008, finger marking at the time of vaccination was introduced to enumerate children vaccinated during a campaign and to improve postcampaign assessment objectivity during market surveys [14]. Lot-quality assurance sampling (LQAS) was initiated in January 2011 as an additional measure of SIA quality, and it was used extensively during 2011–2013.

Poliovirus Surveillance

AFP surveillance quality in Pakistan has been monitored by global performance indicators that include (1) the detection rate of NPAFP cases (to assess surveillance sensitivity) and (2) the proportion of AFP cases with adequate stool specimens (to assess completeness of investigation) [20]. WHO operational targets for Pakistan and other countries with endemic polio transmission are (1) an NPAFP case detection rate of ≥2 cases per 100 000 population aged <15 years (the target for NPAFP case detection per 100 000 persons aged <15 years was increased from ≥1 case during 1994–2005 to ≥2 cases during 2006–2013) and (2) adequate stool specimen collection from >80% of AFP cases, defined as collection of 2 specimens at least 24 hours apart, both within 14 days of paralysis onset, that were shipped on ice or frozen packs to a WHO-accredited laboratory and arrived in good condition.

The poliovirus laboratory at the National Institutes of Health in Islamabad has served as both the National Poliomyelitis Laboratory and the WHO-accredited Regional Reference Laboratory for Poliomyelitis; it provides laboratory support for AFP surveillance in Pakistan and Afghanistan, including primary poliovirus isolation, polymerase chain reaction amplification, and genomic sequencing from both stool specimens and sewage samples [7–18]. Genetic analysis of poliovirus isolates has also been used to identify the circulation of poliovirus lineages not detected by AFP surveillance and to indicate gaps in surveillance sensitivity (all WPVs isolated are sequenced across the interval encoding the major capsid protein [VP1; approximately 900 nucleotides], and results are analyzed to monitor pathways of virus transmission; isolates within a cluster share >95% VP1 nucleotide sequence identity).

RESULTS

Routine Immunization

During 1994–2012, officially reported national routine immunization coverage among infants aged <1 year with OPV3 increased from 65% to 89% [21]. WHO-UNICEF annual estimates of OPV3 coverage, however, were often 5%–15% lower for the same period. WHO-UNICEF–estimated OPV3 coverage rose from 39% in 1994 to a peak of 83% during 2005–2006, with a subsequent decline to 75% during 2011–2012 (Figure 1) [21]. Routine OPV3 coverage among children aged 6–23 months with NPAFP was even lower. On the basis of parental recall or immunization cards, OPV3 coverage during 2009–2012 ranged from 61% to 65% nationally (Figure 1), with a large range among provinces and territories: 18%–29% in Balochistan; 24%–38% in the FATA; 52%–64% in KP; 52%–59% in Sindh; 69%–78% in Punjab; and 83%–100% in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Islamabad Capitol Territory combined.

Figure 1.

Total cases of confirmed poliomyelitis and third-dose oral polio vaccine (OPV3) coverage—Pakistan, 1982–2013. Reported OPV3 coverage denotes the proportion of the target population who received OPV3, as reported by national authorities to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Estimated OPV3 coverage denotes WHO-UNICEF estimates of the proportion of the target population who received OPV3. Non–polio-associated acute flaccid paralysis (NPAFP) case OPV3 coverage denotes the proportion of children who have NPAFP and received OPV3.

SIAs

Reported coverage for SIAs conducted during 1994–2013 was high (>95%), but independent monitoring of campaigns often suggested that actual coverage was lower or that gaps in coverage existed in certain areas or among some groups (Table 1). Post-campaign assessments that relied on parental or caregiver recall often found high coverage as well, but finger-marking surveys, introduced in 2008, documented that actual vaccination coverage was 5%–20% lower during each campaign, with regional variability in coverage unidentified by recall surveys. Similarly, LQAS surveys, introduced in January 2011, documented variable quality of SIA coverage during 2011–2013 but with improvement over time.

During January–November 2008, the percentage of children aged <5 years living in SIA-inaccessible areas increased from 11% to 13% in KP and the FATA overall, affecting 650 000–750 000 children. In KP, the percentage of children aged <5 years who were living in SIA-inaccessible areas increased up to 20% during mid-2009, decreased to <5% by the end of 2009, and further decreased to <1%–2% (<30 000–100 000 children) during January–March 2010 and to <0.2% (<6000 children) during April 2010–December 2011. All areas in KP have been SIA accessible since January 2012, although security arrangements have been enhanced since July 2012. In the FATA, the estimated percentage of children aged <5 years living in SIA-inaccessible areas increased to 30% by late 2009 and ranged from 20% to 31% in 2010 and from 9% to 24% in 2011. During January–July 2012, an estimated 15% of children (nearly 170 000) in the FATA were not accessible. From July 2012 to December 2013, the estimated percentage of targeted children living in SIA-inaccessible areas of the FATA increased to 33%–35% (approximately 377 000–400 000 children) because of security limitations, bans on polio vaccination by some local authorities in the tribal agencies of North and South Waziristan, or both.

During 2008–2013, although large parts of KP and the FATA remained accessible to local vaccination teams during SIAs, security problems often prevented external monitors and supervisors from entering and assessing the quality and coverage of SIAs. In additional areas of the FATA and KP and in Sindh province, targeted attacks against polio workers during SIAs from July 2012 through December 2013 increased costs, limited full implementation, and prevented monitors and supervisors from assessing the quality and coverage of SIAs.

Nationally, use of AFP surveillance data to provide a proxy measure of OPV coverage and, hence, population immunity revealed that 95% and 92% of children aged 6–23 months with NPAFP were reported to have received ≥4 OPV doses through routine immunization or SIAs in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Nationwide, only 2% and 5% of children with NPAFP in 2012 and 2013, respectively, had never received a dose of OPV (so-called 0-dose children). However, there was significant variation in combined routine immunization and SIA OPV coverage by province or area: the percentage of children with NPAFP who received ≥4 OPV doses was >90% in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan, Islamabad Capitol Territory, KP, Punjab, and Sindh during 2012–2013; it was only 78% in Balochistan during both years; and in the FATA, it declined from 71% in 2012 to 35% in 2013. Conversely, the proportion of 0-dose children among those with NPAFP increased in the FATA from 17% in 2012 to 52% in 2013 but remained unchanged in Balochistan (10%), KP (<5%), and elsewhere <1%).

Poliovirus Surveillance

During 1994–1998, AFP surveillance sensitivity and completeness of investigation in Pakistan either were not measured or were below global standards (Table 2). From 1999 to 2004, the annual NPAFP rate increased from 1.3 to 3.5 cases per 100 000 population aged <15 years, and the percentage of AFP cases for which adequate specimens were collected increased from 69% to 88%. During 2005–2013, the average annual number of AFP cases investigated increased to 4903 (compared with an annual average of 1790 cases during 1999–2004), and the annual national NPAFP rate was >5.0 cases per 100 000 population aged <15 years (range among the 6 provinces/territories, 2.4–11.2). The percentage of AFP cases for which adequate specimens were collected was 88%–91% (range, 73%–96%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) Surveillance—Pakistan, 1996–2013

| Non–Polio-Associated AFP Rate, Cases/100 000 Children | Stool Specimen Adequacy, % of Cases Investigated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | AFP Cases, No. | Overall | Range Among Provinces/Areas | Overall | Range Among Provinces/Areas |

| 1996 | 546 | 0.3 | NA | 56 | NA |

| 1997 | 1624 | 0.7 | <1.0 | 43 | 0–68 |

| 1998 | 723 | 0.7 | NA | 61 | NA |

| 1999 | 1329 | 1.3 | NA | 69 | NA |

| 2000 | 1152 | 1.5 | NA | 67 | NA |

| 2001 | 1573 | 2.2 | NA | 83 | NA |

| 2002 | 1802 | 2.8 | >2.0 | 87 | NA |

| 2003 | 2270 | 3.0 | 2.5–4.2 | 89 | 85–91 |

| 2004 | 2615 | 3.5 | 1.5–4.1 | 88 | 82–93 |

| 2005 | 4025 | 5.4 | 3.5–7.6 | 88 | 83–91 |

| 2006 | 4410 | 5.8 | 3.1–8.2 | 89 | 83–92 |

| 2007 | 4425 | 5.6 | 3.3–8.3 | 91 | 83–96 |

| 2008 | 5335 | 6.5 | 3.9–11.2 | 90 | 82–94 |

| 2009 | 5096 | 6.1 | 2.9–9.2 | 90 | 83–96 |

| 2010 | 5382 | 6.9 | 2.8–10.3 | 89 | 81–91 |

| 2011 | 5762 | 7.2 | 2.5–9.7 | 88 | 78–93 |

| 2012 | 5037 | 6.3 | 2.4–9.1 | 89 | 73–92 |

| 2013 | 4658 | 5.8 | 2.5–12.7 | 89 | 82–94 |

The quality of AFP surveillance is monitored by 2 key indicators established by the World Health Organization (WHO): sensitivity of reporting (target: non–polio-associated AFP rate of ≥2 cases per 100 000 children aged <15 years) and completeness of stool specimen collection (target: 2 adequate stool specimens from ≥80% of all persons with AFP that are shipped to a WHO-accredited laboratory and arrive in good condition).

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

WPVs frequently have been isolated from sewage samples collected in all major cities in Pakistan since testing began in mid-July 2009, including large urban areas with an absence of confirmed WPV in reported AFP cases. During 2009, 18 of 46 collected samples (39%) were positive for WPV, primarily from sites in Karachi; WPV3 was the predominant virus isolated. WPV3 has not been detected in sewage samples at any site since October 2010. During 2010 and 2011, WPV1 was detected at all sites, and 79 of 155 samples (51%) and 136 of 204 samples (67%) collected in 2010 and 2011, respectively, were positive. During 2012–2013, WPV1 was isolated frequently from samples in Peshawar (KP), Rawalpindi (Punjab), Hyderabad (Sindh), and Gadaap Town, Karachi (Sindh), but the frequency of isolation declined in other sites. Overall, in 2012, 88 of 239 samples (37%) were WPV1 positive; during 2013, 59 of 295 samples (20%) were WPV1 positive.

WPV and Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus (VDPV) Epidemiology

By 2013, confirmed polio cases declined by ≥93% in Pakistan, compared with the preeradication era, since eradication activities began in 1994. During 1982–1993, when WHO-UNICEF estimates of routine OPV3 coverage were ≤54%, the average annual number of reported polio cases was 1295 (range, 595–3506; Figure 1). During 1994–2003, with an increase in estimated routine OPV3 coverage from 39% to 71% and, beginning in 1994, implementation of SIAs, the average annual number of WPV cases declined to 393 (range, 90–1147), a 70% reduction. The last 2 cases of WPV2 in Pakistan were identified in 1997. During 2004–2013, the average annual number of polio cases declined further, to 85 (range, 28–198), a 78% and 93% decline, compared with 1982–1993 and 1994–2003, respectively (Figure 1).

After initiation of SNIDs with use of a house-to-house vaccination strategy during 1998–1999 and an increase in the number and intensity of SIAs beginning in 2000, confirmed polio cases declined from 199 in 2000 to just 28 WPV cases (27 WPV1 and 1 WPV3) in 2005, the lowest level yet achieved in Pakistan (Figure 1). Even with the successful reduction of the number of cases during 2000–2005, however, 2 major polio transmission zones were identified in Pakistan (extending into Afghanistan), based on genetic analysis of poliovirus isolates, where circulation of WPV persisted despite eradication efforts. The northern transmission zone included KP and the FATA (especially the Peshawar Valley, Khyber Agency, and North and South Waziristan) in Pakistan and bordering areas of eastern Afghanistan. The southern transmission zone extended from southern Punjab, northern Sindh, and Karachi through the Quetta area of Balochistan and into the southern and western regions of Afghanistan.

During 2006–2011, polio cases increased because of quality issues with SIA implementation in some areas, strategic choices made in the use of mOPV1 and mOPV3, and increasing insecurity and problems with access in KP and the FATA. The number of WPV1 cases increased dramatically, from 39 during 2006–2007 to 142 during 2008–2009, with WPV1 circulation in the 2 main transmission zones (53 cases [37%] in KP and the FATA and 39 cases [27%] in Balochistan and Sindh) but also a large outbreak in northern Punjab (47 cases [33%]), where routine OPV3 coverage had declined and fewer SIAs had been conducted during 2007 than in southern Punjab (Figure 1). The outbreak continued into 2010–2011, with a sharp increase in the number of cases after extensive floods in June 2010, affecting most of Pakistan and resulting in large-scale displacement of people. There were 120 and 196 WPV1 cases in 2010 and 2011, respectively, with evidence of several strains of WPV1 circulating throughout Pakistan (Figures 1 and 2).

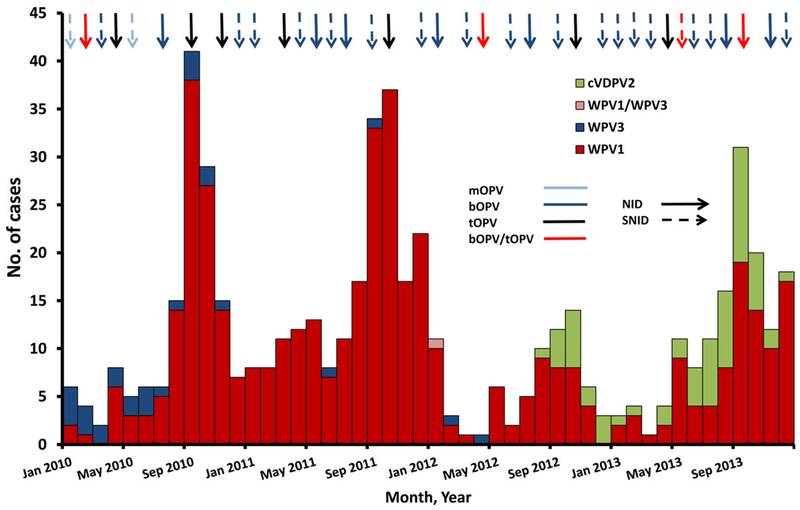

Figure 2.

Number of cases of wild poliovirus types 1 (WPV1), 3 (WPV3), and 1 and 3 (WPV1/WPV3), and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2), by month—Pakistan, 2010–2013. Abbreviations: bOPV, bivalent oral polio vaccine, types 1 and 3; mOPV, monovalent oral polio vaccine, type 1 or 3; NID, national immunization day; SNID, subnational immunization day; tOPV, trivalent oral polio vaccine.

A resurgence of WPV3 in Pakistan occurred during 2006–2011, after reintroduction of a strain of WPV3 from Afghanistan into Balochistan province. Balochistan and Sindh provinces were most affected during 2006–2007 (25 of 33 cases [76%]), and KP and the FATA were most affected during 2008–2009 (49 of 65 cases [75%]). With the introduction of bOPV in 2010 and the use of bOPV or tOPV for almost all SIAs during 2010–2013, the number of WPV3 cases decreased from 16 in 2010 to 2 in 2011 (Figure 2).

With the implementation of the National Emergency Action Plan (NEAP) for polio eradication during 2011 and the augmented NEAP during 2012–2013, the number of WPV cases declined significantly during 2012 and increased primarily in security-affected and inaccessible areas of KP and the FATA during 2013. During 2012, 58 WPV cases (55 WPV1 infections, 2 WPV3 infections, and 1 WPV1/WPV3 coinfection) were reported, compared with 198 WPV cases (196 WPV1 and 2 WPV3) during 2011; 93 cases (all WPV1) were reported during January–December 2013 (Figures 1 and 2). WPV cases were reported in 30 of 157 districts (19%) during 2012 and in 23 districts (15%) during 2013, compared with 60 districts (38%) during 2011. During 2012–2013, 123 of 151 WPV cases (81%) occurred in the FATA or KP (Figure 3). Of 151 WPV cases reported during 2012–2013, 135 (89%) were among children aged <36 months; 72 children (48%) were reported to have received no OPV doses, 19 (13%) received 1–3 OPV doses, and 60 (40%) received ≥4 OPV doses.

Figure 3.

Cases of wild poliovirus types 1 (WPV1), 3 (WPV3), and 1 and 3 (WPV1/WPV3), and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2)—Pakistan, 2012–2013. Abbreviations: AJK, Azad Jammu and Kashmir; FATA, Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Data are current as of 4 February 2014. Each dot represents 1 poliovirus case. Dots are drawn at random within districts.

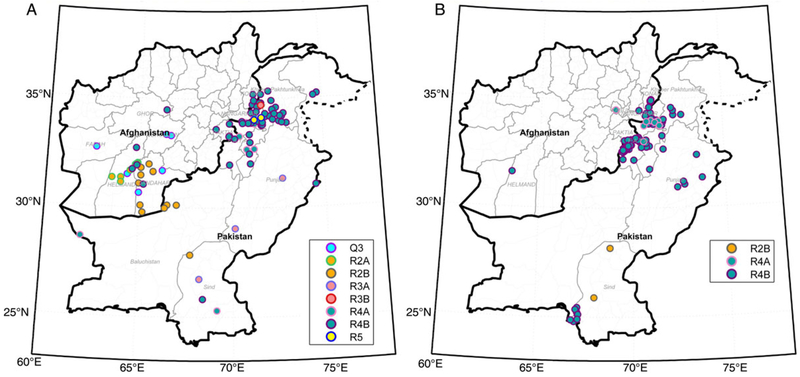

WPV genomic sequencing of isolates from AFP cases identified 6 genetic clusters of WPV1 during 2012 and 3 clusters during 2013 (Figure 4). During 2013, 2 additional WPV1 clusters were detected in sewage samples but not in specimens from AFP cases. During 2012–2013, only 3 WPV3 cases were reported; all were from the same district in the FATA (Khyber), and the WPV3 isolates belonged to a single genetic cluster. The date of onset for the most recent WPV3 case was April 2012. The latest WPV3 isolated from a sewage sample was collected in Karachi in October 2010.

Figure 4.

Genetic profile of wild poliovirus cases in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 2012 (A) and 2013 (B). Maps were created on 30 April 2014. Each dot represents 1 poliovirus case. Dots are drawn at random within districts.

The first circulating VDPV type 2 (cVDPV2) case ever reported in Pakistan was detected in Killa Abdullah district, Balochistan, with onset on 30 August 2012. Genomic sequencing suggested that circulation was undetected for nearly 2 years since emergence. During August 2012–December 2013, 62 cVDPV2 cases were reported: 17 were in Balochistan, 40 were in the FATA (primarily in areas where vaccination teams do not have access), and 5 were in Sindh (Figures 2 and 3). Of the 62 cases reported, 59 (95%) were among children aged <36 months; 36 (58%) had received 0 OPV doses (either routine or SIA), and 10 (16%) had received ≥4 OPV doses.

DISCUSSION

Since 1994, Pakistan has made significant progress toward interruption of WPV transmission. The average annual number of confirmed polio cases has declined by 93% since the preeradication era, and elimination of WPV2 and WPV3 has likely been achieved, with the last cases involving each type identified in 1997 and 2012, respectively.

Intensification of SIAs during 1998–2004 resulted in declining numbers of cases for several years and generated optimism that elimination might soon be achieved. After reaching a nadir during 2005, however, WPV cases increased substantially in number and spread throughout the country during 2006–2011, reaching a peak of 136 and 198 cases during 2010 and 2011, respectively. This surge in WPV cases was attributed to several factors, including low routine OPV3 vaccination coverage; poor quality SIAs because of insufficient political involvement at the federal, provincial, and district levels; strategic choices made in the use of mOPV1 and mOPV3 vaccines during 2005–2010; increasing insecurity and access problems in KP and the FATA during that period; and population displacement after severe flooding in mid-2010.

The crisis created by widespread WPV transmission in 2010–2011 led to the development of the 2012 Enhanced NEAP [22]. In 2012, the quality of SIAs improved after implementation of management and accountability strategies included in the NEAP. The number of WPV cases that year declined 70%, compared with the value from 2011 (58 cases vs 198 cases), and they were more geographically restricted. In 2013, an increased number of WPV cases (93) was reported but with further geographic restriction, based on AFP and environmental surveillance, primarily to high-risk areas of the FATA and KP; and WPV1 circulation apparently was interrupted in the Quetta block, Balochistan, one of the historical reservoir areas. WPV3 has not been detected in any stool or sewage sample in Pakistan for >1 year. During 2012, however, cVDPV2 emerged in the Quetta block because of long-standing low routine vaccination coverage and poor-quality SIAs [23]. More importantly, during 2013, WPV1 transmission in the FATA intensified, and cVDPV2 originating from the Quetta block spread quickly in certain areas of the FATA where conflict and local bans on polio vaccination prevented access by vaccination teams for >1 year.

Tragically, since July 2012, targeted attacks, resulting in the deaths of 22 polio workers and 4 police officers and injuries to many others, have seriously compromised implementation of SIAs in many areas of the FATA, KP, and Karachi. SIAs were resumed in affected areas of the FATA, KP, and Karachi after initial suspension following the attacks against polio workers. However, the quality of vaccination activities in these areas during 2013 was affected because of strategies implemented to ensure the safety of vaccinators, such as conducting SIAs without notice, reducing or suspending house-to-house visits in some locales, conducting campaigns in 1 day, and cordoning areas to create a security zone. Furthermore, cancellation of post-SIA surveys prevented assessments of SIA quality and management of vaccination team performance problems.

In addition, in the North and South Waziristan agencies of the FATA, bans by local authorities have prohibited polio vaccination for approximately >350 000 children since June 2012. Ongoing efforts have been made with the assistance of political and religious leaders to reverse the ban on polio vaccinations and negotiate access, but they had not been successful by the end of 2013. In the interim, vaccination sites have been set up at transit points serving North Waziristan and other areas to reach children entering or exiting SIA-inaccessible areas. Efforts to prevent WPV transmission to other areas of Pakistan have been undertaken by increasing the frequency and variety of scheduled SIAs and by aggressively responding to cases in accessible areas with outbreak response immunization campaigns.

Major improvements in polio program performance during 2012–2013 and the decreased extent of transmission of WPV in Pakistan suggest that the successful eradication of polio might be achieved. However, the high proportion of children infected with WPV or with NPAFP who are underimmunized and the simultaneous WPV1 and cVDPV2 outbreaks in the FATA during 2013 highlight the serious consequences to population immunity that have resulted from conflict and insecurity. WPV1 from inaccessible areas of the FATA has spread to other areas in Pakistan and to other countries. All WPV1 cases in Afghanistan in 2013 occurred in the eastern region adjoining the FATA and were caused by WPV1 originating in the FATA. WPV1 transmission in Egypt, Iraq, Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, and Syria during 2012–2013 can be linked to WPV1 originating in Pakistan [24]. This situation puts recent achievements in Pakistan at risk for reversal and puts achievement of the objective of global polio eradication in peril. Enhanced efforts by humanitarian, religious, and governmental bodies to improve community acceptance of vaccination and reach children in conflict-affected and security-compromised areas of Pakistan will be necessary to interrupt all poliovirus transmission in Pakistan.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Laura K. Wright, Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, for preparation of the 4-panel map of cases; and Elizabeth Henderson, Division of Viral Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for preparation of the maps of poliovirus type 1 strains.

Financial support.

This work was supported by the World Health Organization (to M. Z., M. K., N. A., and E. D.) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (J. P. A.).

Supplement sponsorship.

This article is part of a supplement entitled “The Final Phase of Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategies for the Post-Eradication Era,” which was sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Notes

Potential conflicts of interest.

All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward eradication of polio—worldwide, January 2011–March 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:335–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population prospects, 2012 revision. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Excel-Data/population.htm. Accessed 19 May 2014.

- 3.World Health Organization. Demographic, social and health indicators for countries of the Eastern Mediterranean. http://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMROPUB_2013_EN_1537.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 19 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1988–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1995; 44:809–11, 817–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan, 1994–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999; 48:121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan, 1999–June 2000. MMWR 2000; 49:758–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan and Afghanistan, January 2000–April 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002; 51:521–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, January 2002–May 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52:683–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, January 2003–May 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:634–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, January 2004–February 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 54:276–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan and Afghanistan, January 2005–May 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006; 55:679–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan and Afghanistan, January 2006–February 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007; 56:340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan and Afghanistan, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57: 315–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58:198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:268–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, January 2010–September 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:1523–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan and Pakistan, January 2011–August 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:790–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Pakistan, January 2012–September 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:934–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2012 revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/pak.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluating surveillance indicators supporting the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:270–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system—Pakistan. http://apps.who.int/immunization_ monitoring/globalsummary/countries?countrycriteria%5Bcountry% 5D%5B%5D=PAK. Accessed 19 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government of Pakistan. National emergency action plan 2013 for polio eradication.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update on vaccine-derived polioviruses—worldwide, April 2011–June 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:741–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Polio outbreak in the Middle East—update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. http://www. who.int/csr/don/2014_3_21polio/en/. Accessed 19 May 2014. [Google Scholar]