Abstract

The last two decades have seen many advances in regenerative medicine, including the development of tissue engineered vessels (TEVs) for replacement of damaged or diseased arteries or veins. Biomaterials from natural sources as well as synthetic polymeric materials have been employed in engineering vascular grafts. Recently, cell-free grafts have become available opening new possibilities for the next generation, off-the-shelf products. These TEVs are first tested in small or large animal models, which are usually young and healthy. However, the majority of patients in need of vascular grafts are elderly and suffer from comorbidities that may complicate their response to the implants. Therefore, it is important to evaluate TEVs in animal models of vascular disease in order to increase their predictive value and learn how the disease microenvironment may affect the patency and remodeling of vascular grafts. Small animals with various disease phenotypes are readily available due to the availability of transgenic or gene knockout technologies and can be used to address mechanistic questions related to vascular grafting. On the other hand, large animal models with similar anatomy, hematology and thrombotic responses to humans have been utilized in a preclinical setting. We propose that large animal models with certain pathologies or age range may provide more clinically relevant platforms for testing TEVs and facilitate the clinical translation of tissue engineering technologies by increasing the likelihood of success in clinical trials.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease claims 801,000 deaths in the United States annually, according to the 2017 AHA (American Heart Association) statistic. The estimated global healthcare cost for cardiovascular disease by year 2030 is projected to exceed $1,044 Billion USD. One of the most prevalent among heart diseases is coronary artery blockage (45.1% of all cardiovascular ailments), leading to heart attacks or stroke [1]. The established surgical remedy involves the harvest of an autologous vein or artery, which is then transplanted to “bypass” the diseased region of the coronary artery, restoring regular blood flow back into the heart. Harvesting an autologous vessel from an elderly person, or patients suffering from other complications such as hypertension, diabetes, or previous bypass or shunt procedures, often does not yield viable graftable vessel segments [1]. This prompts for alternate tissue engineered vessels (TEVs) to be made readily available “off-the-shelf”[2–4]. In addition to their application for the treatment of coronary artery disease, TEVs can also be employed to treat congenital heart disease, peripheral artery diseases, chronic vein insufficiency as well as their utilization as dialysis shunts for treatment of kidney diseases, especially for diabetic patients. Existing technologies utilize cell-based approaches and bio-reactor processing which are time-consuming and synthetic products which may result in unfavorable outcomes, due to lack of development of biological function [3, 5].

An ideal TEV should develop biological function, and be similar in structure and mechanical properties to the native blood vessel into which it is implanted. Remodeling of the TEV should result in a lumen with a confluent monolayer of endothelial cells, surrounded by a medial wall containing collagen, elastin and circumferentially aligned smooth muscle, capable of contractile function and control of blood flow. A major challenge facing most research groups is the correct choice of an animal model where the TEVs may be tested. Small animal models such as mice allow genetic manipulation, thereby providing a suitable platform to study cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the remodeling processes. However, larger animal models provide a more physiologically relevant platform to study graft remodeling, due to physiological similarities with humans. That being said, hematologic and hemostatic processes such as clotting cascades, secondary thrombogenic events and cell infiltration and migration patterns in different species may vary from those in humans. Processes such as inflammation and immune responses must also be considered when making the choice of the animal model.

2. Biomaterials for vascular tissue engineering

The choice of biomaterial is critical for the construction of a successful TEV (Tissue Engineered Vessel). The appropriate porosity, allowing for cell migration and supporting natural ECM (extracellular matrix) secretion, is important to graft patency as is a healthy endothelial layer. A canine study, which examined the effects of biomaterial and endothelial cell seeding revealed that simply applying endothelial lining in dacron and e-PTFE (expanded-Polytetrafluoroethylene) grafts was not a deciding factor for patency, but, the biomaterial used to construct the vessel played a significant role [6]. The study results concluded that isodiametric naturally harvested scaffolds performed best to maintain patency [6]. Graft porosity allows for cell adherence as well as migration and diffusion of important healing factors critical to the remodeling responses [7–9]. In fact, porous biomaterials might allow for capillary ingrowth, leading to transmural endothelialization of the grafts [10]. Similarly, the lumen of perforated Goretex® implanted in the canine aorta was lined with host endothelial cells faster as compared to solid grafts [7]. Healing and stabilization of implanted grafts mostly occurs through fibroblast transmural migration. In fact, when the tissue surrounding the implant site was preserved and rewound around the porous TEV, fibroblast migration from perivascular tissue enhanced patency [8]. Although natural biomaterials provide sufficient porosity and mechanical strength, synthetic biomaterials can be tuned more easily by electrospinning or 3D printing techniques to make off-the-shelf customizable grafts.

2.1 Synthetic materials

The main advantage of using synthetic materials is the abundance in availability, relative ease in controlling their desired mechanical properties, porosity and cell adhesiveness, as well as quality control leading to reduced batch-to-batch variability. Electrospinning polymers with desired natural biomaterials yields very good materials for TEVs. For example, electrospinning poly-L-lactide/PCL copolymer with collagen yielded high tensile strength and proved to promote cell migration and adhesion [11]. Likewise, by manipulating inter-nodal distances of polymer fibers within PTFE grafts, transmural endothelial cell migration leading to capillary formation could be achieved in vivo [10]. It has been observed that the size of fibers used for electrospinning has been shown to control porosity and the surface are available for cell adhesion. Specifically, electrospinning with microfibers increases porosity, while spinning with nanofibers enables perfusion flow through the graft material leading to increased cell density, as tested in vitro in a bioreactor [12].

The function of synthetic biomaterials has been enhanced by functionalization with biological active signals such as growth factors. For example, immobilizing VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) on PTFE grafts using standard EDC chemistry and HAS (Human Serum Albumin) electrostatic linkages enabled endothelial cell migration in vivo [13]. Interestingly, Wu et al. employed the biodegradability and cell homing capacity of polyglycerol sebacate elastomer to create a “template” for neoartery formation in vivo [14]. Although synthetic biomaterials are a convenient option for tissue engineering advances, natural biomaterials possess natural ECM for enhanced host cell invasion and remodeling.

2.2 Natural biomaterials

Natural biomaterials include fibrin, collagen, and hyaluronic acid as well as decellularized tissues e.g. decellularized arteries that maintain their ECM composition and mechanical properties, thereby providing robustness to the scaffold. Fibrin has been used in the past as a polymer suitable for vascular tissue engineering as well [15]. Our group has used fibrin in an ovine model in the past to successfully implant TEVs in jugular veins of lambs [16]. SIS (small intestinal submucosa) is a collagen-rich biomaterial, which has been used extensively for regenerative medicine, particularly as an arterial graft [17, 18]. Another study from our group evaluated the development of a TEV composed of both fibrin and SIS as a composite biomaterial, which allowed for unprecedented host cell infiltration [19]. This study revealed that smooth muscle cell seeding was not necessary in the medial layer, as infiltrated donor cells in the graft wall were capable of forming a functional contractile smooth muscle layer and depositing new ECM for remodeling. In a subsequent study, we employed SIS to develop a truly cell-free vascular graft by immobilizing VEGF on the graft lumen (Fig. 1). When implanted into the carotid arteries of sheep, the SIS-based, VEGF-fortified grafts were fully endothelialized within one month and exhibited high patency rates and excellent remodeling, providing truly cell-free, off-the-shelf vascular grafts for clinical applications [20]. Another potential advantage of natural biomaterials, such as collagen, fibrin, hyaluronic acid and other ECM based materials is their ability to recruit host cells such as macrophages [21, 22], which are well-known to induce an angiogenic response and facilitate the ingrowth of connective tissue by secretion of cytokines [22, 23]. This has important consequences for the innervation and host integration of the implanted tissue [21].

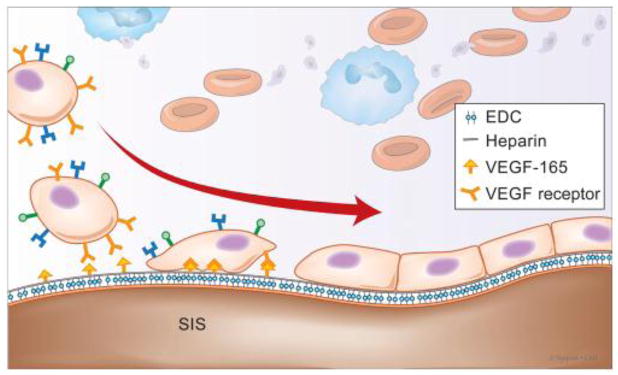

Figure 1.

Schematic representing the crosslinking of heparin onto collagen fibers of SIS tubed in the vessel lumen, followed by binding of VEGF via the heparin binding domain. Cells presenting VEGF receptors in the blood were then captured by the VEGF, forming a confluent endothelial lumen.

2.3 Scaffold-free TEVs

Self-assembled TEVs, or cell-sheet engineered grafts are based on the ability of SMCs and fibroblasts to form cell sheets with strong intercellular connections and the ability to secrete high levels of the ECM, both of which contribute to the mechanical strength of the resulting cylindrical structures [24]. These TEVs were later decellularized and seeded with autologous endothelial cells from the patient’s skin and were transplanted successfully as dialysis access grafts, in a clinical trial [25, 26]. Although the long-culture times pose a serious challenge for production and scale-up, these grafts were shown to be amenable to freeze-drying and subsequent endothelialization, which makes them available on demand. However, the need for endothelialization calls for additional processing steps and isolation and culture of autologous endothelial cells, and therefore these grafts are not truly cell-free.

3. Animal models of vascular disease for evaluation of TEVs

The majority of cardiovascular grafting procedures are performed in the elderly, with 66% of deaths due to cardiovascular ailments occurring in patients 75 years or older, with age being the primary risk factor for occurrence of these conditions [27]. In addition, these patients are likely to suffer from comorbidities, including hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, etc., which may have significant effects on SMC and EC function [28], ultimately affecting TEV patency and remodeling. However, evaluation of TEVs is typically performed in healthy, young animals, which may not provide accurate representations of the clinical reality. For these reasons, we propose that animal models of cardiovascular diseases may provide a better test bed for evaluation of vascular grafts. Small animal models, especially mice have been employed to study mechanisms of cardiovascular physiology and disease, due to the large variety of genetic manipulations available. On the other, large animal models are essential for clinically relevant studies due to their anatomic and physiological similarities with humans (Fig. 2).

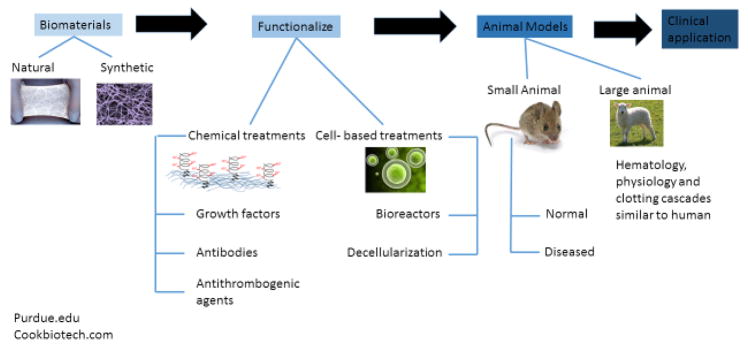

Figure 2.

Flow chart depicting the various components of vascular tissue engineering and different approaches. Natural or synthetic biomaterials are functionalized either with cell-based technologies or by conjugation of anti-thrombogenic agents, antibodies or growth factors, enabling them to capture endothelial and smooth muscle cells within the host. These are then tested in small animal models, such as mice, which allow for genetic manipulation to study comorbidities and disease models. Large animal models, with similar physiology, hematology and clotting cascades as human are then chosen to more accurately represent a pre-clinical study. Successful studies may be translated to the clinic.

3.1 Small animal models

Several mouse models have been developed to reproduce the complications of cardiovascular maladies including atherosclerosis, thrombosis, inflammation and aneurysms as well as their underlying causes such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and aging. These models have been used in combination with diet, inflammatory drugs, smoking and lack of exercise to account for variables added to simulate human lifestyle.

3.1.1 Atherosclerosis models

Atherosclerotic lesions occurring in the coronary artery are the most common form of cardiovascular disease, which can lead to heart attacks or stroke, if not treated properly. The apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is the major factor involved in catabolism of triglycerides. ApoE −/− mice develop atherosclerotic lesions, albeit not in the coronary artery, which is the most susceptible location in human vasculature due to the associated hemodynamics and anatomy [29, 30]. In addition, mice can produce ApoB to replace ApoE in their livers, whereas humans can only produce limited quantities of ApoB, restricted only to the intestinal epithelium. However, ApoE−/− mice are similar to humans in that they develop monocytosis and the lesions get aggravated with high fat diet, addition of AngII, or LDL receptor deficiency (Ldlr−/−).

Ldlr−/−mice have also been utilized as models of atherosclerosis, as they develop hypercholesterolemia, comparable to humans [31]. Indeed, these mice are susceptible to obesity, and high dietary cholesterol or cholate exacerbate the accumulation of inflammatory cytokines, resulting in high numbers of macrophages in adipose tissue [31]. Disease progression and tissue pathology in lesions developed in arteries of this model are strikingly similar to that of humans [31, 32]. One significant difference was the absence of CETP (cholesteryl ester transfer protein) in the mouse models, in contrast to high levels of CETP in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which places them at high risk levels for coronary artery disease [31–33]. In combination with Ldlr deficiency, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) have been identified as mediators of chronic inflammation, leading to intensified lesions, particularly in the abdominal aorta of mice. TLRs are critical to pathogen recognition and are involved in innate immunity. In particular, TLR-2 has been identified as a key player in evolution of lesions, however TLR-1 and TLR-6 are capable of forming heterodimers with TLR-2, modulating the inflammatory responses [34].

In addition to mouse models, the WHHL (Watanabe Hereditary Hypercholesterolemia) rabbit model is often used in studies of chronic atherosclerosis, mostly due to similar enzyme expression levels as humans, as well as because it exhibits formation of calcified and necrotic lesions, which are indicative of advanced coronary artery disease [35].

3.1.2. Thrombosis and aneurysm models

While atherosclerotic mice models have been studied thoroughly, thrombosis following stenting and grafting procedures in patients undergoing bypass procedures for the treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD) continues to be a debilitating problem. TF−/− (tissue factor negative) mice have been employed to study thrombosis. In particular, vascular smooth muscle-specific loss of TF was developed by floxing CRE/SM22 sites to obtain TFflox/flox/SM22αCre+/− mice to model acute thrombosis. Within ten weeks of age, mice subjected to ferric chloride-induced injury developed advanced thrombosis including cardiac fibrosis and inter-cardiac hemorrhage, characteristics of human disease [36].

Another vascular disease condition that has been well studied is the formation and rupture of aneurysms in the arterial walls. CXCR3 receptor (chemokine receptor family) and its interaction with CXCL10 ligand (also known as interferon-γ induced protein-10) play a key role in release of chemo-attractants from endothelial cells in vessels. CXCL10−/− mice develop aneurysms by interrupting the interferon release, which is exacerbated by AngII treatment. These animals exhibit vasodilation and rupture kinetics with underlying molecular mechanisms analogous to humans [37]. Interferon therapy is often used along with surgical intervention to treat brain lesions and prevent relapses of dilation. Studies with CXCL10−/−ApoE−/− mice have established the role of ApoE in spirally dissected aneurysms and rupture, equivalent to human complications [38]. Cytokines and chemo-attractants are critical players in disease onset and progression, and mouse models have been instrumental in identifying such mechanisms, which are similar for humans as well.

3.1.3. Hypertension

Another risk factor for CAD is hypertension. AngII−/− and AT1−/− mice were critical in establishing ACE inhibitors and AT1 antagonists as potential treatments for hypertension [39]. Transgenic rats with an additional inducible REN-2 gene, TGR(mREN2)27 enabled studies of the Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) [40]. It was observed that homozygous (REN2 −/−) mutant rats exhibited higher mortality rates and more acute increases in blood pressure as compared to heterozygous animals. AT1 receptor antagonist dup753 reduced REN-2 induced hypertension, suggesting that AT1 may be a good drug target for treatment of the disease [40].

Spontaneously hypertensive rats, or SHRs, develop chronic hypertension by 4–6 weeks of age and can be obtained by inbreeding of pre-hypertensive Wistar-Kyoto rats. They exhibit increased cardiac output and total peripheral resistance, in addition to end organ damage [41]. When compared to Wistar-Kyoto rats, SHRs exhibited higher serum levels of MCP-1 and higher numbers of ED-1 positive macrophages in the vascular walls [42].

Another well-accepted way of inducing hypertension is a high salt diet. Dahl’s salt sensitive rats are an excellent model, where high sodium intake increased the blood pressure of these animals [43, 44]. Withdrawal of salt, however, only reverted a third of the test cases back to normal blood pressure. BUN (blood urea nitrogen) levels were affected for a short period, but renal function remained relatively normal [43, 45]. Dahl’s salt sensitive rats, however displayed significantly increased numbers of T lymphocytes in the kidneys, likely as a consequence of hypertension [44]. Another interesting study showed that increased infusion of NOS could not recover the vasoconstrictive effects of salt induced hypertension, which could indicate superoxide formation [46].

Finally, one study from the Breuer group examined the effect of MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) in the patency and remodeling of tissue engineered vascular grafts using two mouse models: i) a mouse model depleted of macrophages using clodronate liposomes; and (ii) the CD11b-diphtheria toxin-receptor (DTR) transgenic mouse model, which enables macrophage depletion by administration of diphtheria toxin. They reported that the presence of monocytes, and their maturation to M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype was crucial in attracting host cells during graft healing. Inhibition of macrophages decreased graft stenosis but also inhibited vascular neotissue formation, as evidenced by the absence of endothelial and smooth muscle cells and collagen. MCP-1 played an important role in smooth muscle infiltration in the vascular wall, leading to gain of function, as evidenced by enhanced patency and long-term performance of the grafts [47–49].

Table 1 summarizes a number of studies that employed small animal models to study molecular mechanisms of vascular disease. Given that most patients receiving graft implantation treatments suffer from comorbidities, utilizing disease models to study graft implantation and remodeling may predict post-grafting complications, thereby adding significant input to tissue engineering and regenerative medicine approaches. That being said, larger animal models provide clinically relevant data and must be utilized to study efficacy, performance and remodeling of grafts in a more human-like physiological setting.

Table 1.

| Study Description | Complication | Similarity to human | Differences from human |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− mice leading to altered metabolism of triglycerides [1, 2] | Atherosclerosis |

|

|

| Ldlr−/− mice [3] | Hypercholesterolemia |

|

|

| WHHL Rabbit [4] | Atherosclerosis |

|

None |

| TF−/− mice, smooth muscle specific knockout [5] | Thrombosis |

|

|

| CXCL10−/− mice, addition of AngII [6, 7] | Aneurysm formation and rupture |

|

|

| Role of MCP1 during graft healing [8] | Healing and Remodeling |

|

|

| AngII−/−and AT1−/− mice [9] | Hypertension |

|

|

| Spontaneously hypertensive and Dahl’s rats [10, 11] | Hypertension |

|

|

Fazio S, Babaev VR, Murray AB, Hasty AH, Carter KJ, Gleaves LA, et al. Increased atherosclerosis in mice reconstituted with apolipoprotein E null macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:4647–52.

Getz GS, Reardon CA. Apoprotein E as a lipid transport and signaling protein in the blood, liver, and artery wall. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S156–61.

Subramanian S, Han CY, Chiba T, McMillen TS, Wang SA, Haw A, 3rd, et al. Dietary cholesterol worsens adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and atherosclerosis in obese LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:685–91.

Shiomi M, Ito T. The Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbit, its characteristics and history of development: a tribute to the late Dr. Yoshio Watanabe. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:1–7.

Wang L, Miller C, Swarthout RF, Rao M, Mackman N, Taubman MB. Vascular smooth muscle-derived tissue factor is critical for arterial thrombosis after ferric chloride-induced injury. Blood. 2009;113:705–13.

King VL, Lin AY, Kristo F, Anderson TJ, Ahluwalia N, Hardy GJ, et al. Interferon-gamma and the interferon-inducible chemokine CXCL10 protect against aneurysm formation and rupture. Circulation. 2009;119:426–35.

van den Borne P, Quax PH, Hoefer IE, Pasterkamp G. The multifaceted functions of CXCL10 in cardiovascular disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:893106.

Hibino N, Yi T, Duncan DR, Rathore A, Dean E, Naito Y, et al. A critical role for macrophages in neovessel formation and the development of stenosis in tissue-engineered vascular grafts. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:4253–63.

Dai Q, Xu M, Yao M, Sun B. Angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonists exert anti-inflammatory effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats. British journal of pharmacology. 2007;152:1042–8.

Bader M, Zhao Y, Sander M, Lee MA, Bachmann J, Bohm M, et al. Role of tissue renin in the pathophysiology of hypertension in TGR(mREN2)27 rats. Hypertension. 1992;19:681–6.

Dahl LK. Effects of chronic excess salt feeding. Induction of self-sustaining hypertension in rats. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1961;114:231–6.

3.2 Large Animal Models

Large animal models have been utilized in vascular tissue engineering for several years and a comprehensive summary of such models has been discussed in previous review articles published by our group [50, 51]. Here we focus on cardiovascular disease models that have been used or have the potential to be used for testing vascular grafts.

3.2.1. Rabbits

Bilateral common carotid ligation in rabbits is a common model platform that has been used to replicate aneurysm formation in the basilar terminus, which has been reported in humans when blood flow through the carotid arteries is interrupted. In contrast to rabbits, common carotid ligation in rats resulted in fewer pathological and hemodynamic changes, indicating that rats may not be a good model to study flow-induced aneurysmal remodeling [52]. Rabbits have also been employed to study intracranial aneurysms and aneurysm-induced remodeling of the vascular wall leading to internal elastic lamina loss, medial thinning and luminal bulging [53]. Such destructive remodeling has been attributed to high local hemodynamic forces that yield a combination of high wall shear stress (WSS) and positive WSS gradient [54]. While SMC mount an inflammatory response to such forces, endothelial cells exhibit an anti-coagulative, proliferative and pro-remodeling phenotype, which is required to reestablish vessel homeostasis [55]. Rabbit aneurysmal models are also employed as testing platforms for development of new flow-diverters, which can be placed via catherization procedures to treat aneurysmal risk areas and stop rupture [56]. Finally, abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) models have also been developed in rabbits using short-term incubation with elastase and calcium chloride [57]. Using the rabbit AAA model, it was shown that treatment with Aliskiren – a renin inhibitor – resulted in inhibition of NF-κB, MCP-1 and MMP-9, reducing macrophage invasion and preventing weakening of the vessel wall [58].

3.2.2. Sheep

Congenital heart disease affects 1% of all babies born in the United States, and 1 in 4 of these are critical, needing immediate surgery to replace arteries and redirect blood flow within the first year of their life [59]. Coarctation of the aorta, pulmonary atresia, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome are critical congenital heart defects that require replacement grafts [59, 60]. Most cases of congenital heart disease require re-intervention surgeries as the artificial grafts may not grow with the patients’ vasculature [61]. A recent study utilizing fibrin-based vascular grafts, grown in bioreactors and then decellularized before implantation into growing lambs demonstrated that these grafts are capable of growing along with the host [62]. Recently, our group also tested cell-free, SIS-based and VEGF-fortified TEVs in neonatal sheep (2mm diameter grafts) with very promising results. Specifically, we found that the A-TEVs remained patent, remodeled and completely integrated over time, suggesting that these grafts may also provide a potential off-the-shelf solution for pediatric complications (unpublished data).

In addition, we developed an ovine animal model of hypertension using the one-kidney-one-clip model, in order to study the effects of the disease on arterial implantation [63]. By modifying the Renin-Angiotensin balance, this model was developed to study the effects of sustained hypertension on cardiac hypertrophy, and in particular, left ventricular remodeling [64]. Using this model, we tested the interpositional implantation of autologous carotid artery grafts (CAG) or facial vein grafts (FVG) into the carotid arteries of hypertensive (HT) or normotensive sheep (NT). CAG and FVG were chosen for the following reasons: (i) easy access to the neck of the animal; (ii) in contrast to jugular vein, FV is of similar size to CA; and (iii) our prior experience with TEV implantation into the carotid artery, where we are also planning to also test our cell-free TEVs in this hypertensive model.

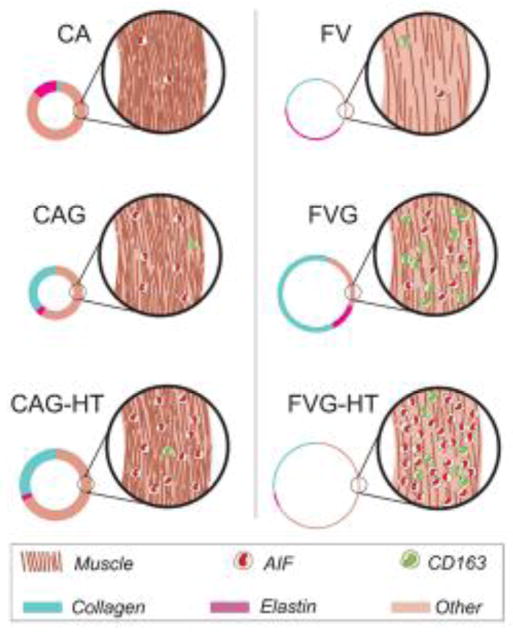

In NT conditions, FVG demonstrated thickening of vessel wall to match the native carotid artery they were grafted into; increased number of smooth muscle cells within the vessel wall; as well as reduced elastin and increased collagen content (Fig. 3). Interestingly, CAG exhibited significantly reduced mechanical properties under HT or NT conditions, which was attributed to reduced SMC numbers, as well as collagen and elastin content. On the other hand, FVG were affected to a higher extent by HT as compared to CAG, and this was attributed to pro-inflammatory remodeling. Overall, CAG autologous arteries performed better than FVG in HT animals, while FVG and CAG performed similarly as replacement grafts in NT animals.This result may be attributed to infiltrationof vascular grafts by pro-inflammatory macrophages in HT animals. In contrast, the prevailing macrophages infiltrating the grafts in NT animals were of anti-inflammatory phenotype(Fig. 4 ). This pre-clinical, one-kidney-one-clip modelmay be employed to improve our understanding of the effects of hypertension in vascular remodeling and provide guiding principles for engineering vascular grafts for hypertensive patients.

Figure 3.

Trichrome staining at one month post graft placement. Images of stained tissue sections of FVs, CAs and FVGs, CAGs under NT and HT conditions. Top panels show entire cross-section of the grafts (Scale bar= 2 mm), and lower panels are magnified images (Scale bar= 200 μm).

Figure 4.

Facial vein (FV) and Carotid arteries (CA) were autologously harvested and placed in to the carotid arteries of normotensive (NT) or Hypertensive (HT) animals. Under NT conditions, FVG were remodeled to resemble native carotids, while CAG showed decline of mechanical properties, structure and function. Under HT conditions, CAG performed better than FVG, which were mostly populated by pro-inflammatory macrophages leading to degradation of the graft.

3.3.3. Baboons

Although primate models are the closest in anatomy to human physiology, their use is hindered by the high expense and ethical concerns. Recent studies by Niklason’s group employed baboons to examine PGA or decellularized artery based vascular grafts as arteriovenous shunts for dialysis access [65]. More recently, these grafts have been used in a human clinical trial [66], where only 28% of implanted dialysis shunts exhibited primary patency, while secondary patency at one year increased to 89% following thrombus removal. Interestingly, conjugation of azido-thrombomodulin on the lumen of ePTFE grafts was found to be more effective in controlling thrombosis and enhancing patency rates as compared to traditional heparin coating, in a baboon model of acute thrombosis [67]. Inhibition of Factor XII by monoclonal antibodies also reduced platelet and fibrin accumulation downstream of grafts that were implanted as arteriovenous shunts [68]. Finally, baboons were used to evaluate intimal hyperplasia in arteriovenous grafts. Interestingly, ePTFE conduits exhibited significant venous intimal hyperplasia due to compliance mismatch and abundant presence of proinflammatory macrophages. In contrast, TEVs developed only mild venous hyperplasia, suggesting that biological vascular grafts may be superior to synthetic ones, at least in part due to differences in the inflammatory response of the host [69].

4. Conclusion

Research and technology developed over the last decade have progressed tremendously in both providing off-the-shelf alternatives for replacement vessels in the clinic, as well as development of animal models of disease, which have improved our understanding of disease progression and complications. Currently, evaluation of TEV technologies is carried out using young, healthy animals, which may provide a different microenvironment than that of human patients who are likely to suffer from multiple comorbidities. Therefore, animal models of human disease may be necessary to provide more realistic hosts that may reveal potential effects of the diseased microenvironment on TEV patency and remodeling. Currently, most disease models are based on rats or mice mostly due to the ease of genetic manipulation. However, development of disease models based on larger animals will likely have great impact not only on the molecular understanding of human disease but also on the evaluation of TEVs and other tissue engineering technologies. Finally, the majority of cardiovascular grafting procedures are performed in the elderly [70] and age is the primary risk factor for disease occurrence and development [71], suggesting that preclinical assessments of TEVGs need to be performed in aged animal models in order to increase its predictive power of the human condition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 HL086582 (S.T.A.) and R43OD023242 (S.R., D.D.S., S.T.A.) and the New York Stem Cell Science NYSTEM (Contract #C30290GG, S.T.A.).

Footnotes

Disclosure: All authors have financial interest in Angiograft LLC.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang AH, Niklason LE. Engineering of arteries in vitro. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2103–18. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1546-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naito Y, Shinoka T, Duncan D, Hibino N, Solomon D, Cleary M, et al. Vascular tissue engineering: towards the next generation vascular grafts. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2011;63:312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peck M, Gebhart D, Dusserre N, McAllister TN, L'Heureux N. The evolution of vascular tissue engineering and current state of the art. Cells, tissues, organs. 2012;195:144–58. doi: 10.1159/000331406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zilla P, Bezuidenhout D, Human P. Prosthetic vascular grafts: wrong models, wrong questions and no healing. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5009–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herring M, Gardner A, Peigh P, Madison D, Baughman S, Brown J, et al. Patency in canine inferior vena cava grafting: effects of graft material, size, and endothelial seeding. Journal of vascular surgery. 1984;1:877–87. doi: 10.1067/mva.1984.avs0010877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusaba A, Fischer CR, 3rd, Matulewski TJ, Matsumoto T. Experimental study of the influence of porosity on development of neointima in Gore-Tex grafts: a method to increase long-term patency rate. The American surgeon. 1981;47:347–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sterpetti AV, Hunter WJ, Schultz RD, Farina C. Healing of high-porosity polytetrafluoroethylene arterial grafts is influenced by the nature of the surrounding tissue. Surgery. 1992;111:677–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinberg CB, Bell E. A blood vessel model constructed from collagen and cultured vascular cells. Science. 1986;231:397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.2934816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clowes AW, Kirkman TR, Reidy MA. Mechanisms of arterial graft healing. Rapid transmural capillary ingrowth provides a source of intimal endothelium and smooth muscle in porous PTFE prostheses. The American journal of pathology. 1986;123:220–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon IK, Matsuda T. Co-electrospun nanofiber fabrics of poly(L-lactide-co-epsilon-caprolactone) with type I collagen or heparin. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2096–105. doi: 10.1021/bm050086u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2796–805. doi: 10.1021/bm060680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crombez M, Chevallier P, Gaudreault RC, Petitclerc E, Mantovani D, Laroche G. Improving arterial prosthesis neo-endothelialization: application of a proactive VEGF construct onto PTFE surfaces. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu W, Allen RA, Wang Y. Fast-degrading elastomer enables rapid remodeling of a cell-free synthetic graft into a neoartery. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1148–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaikh FM, Callanan A, Kavanagh EG, Burke PE, Grace PA, McGloughlin TM. Fibrin: a natural biodegradable scaffold in vascular tissue engineering. Cells, tissues, organs. 2008;188:333–46. doi: 10.1159/000139772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swartz DD, Russell JA, Andreadis ST. Engineering of fibrin-based functional and implantable small-diameter blood vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1451–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00479.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lantz GC, Badylak SF, Coffey AC, Geddes LA, Blevins WE. Small intestinal submucosa as a small-diameter arterial graft in the dog. Journal of investigative surgery : the official journal of the Academy of Surgical Research. 1990;3:217–27. doi: 10.3109/08941939009140351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shell DHt, Croce MA, Cagiannos C, Jernigan TW, Edwards N, Fabian TC. Comparison of small-intestinal submucosa and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene as a vascular conduit in the presence of gram-positive contamination. Annals of surgery. 2005;241:995–1001. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000165186.79097.6c. discussion -4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Row S, Peng H, Schlaich EM, Koenigsknecht C, Andreadis ST, Swartz DD. Arterial grafts exhibiting unprecedented cellular infiltration and remodeling in vivo: the role of cells in the vascular wall. Biomaterials. 2015;50:115–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koobatian MT, Row S, Smith RJ, Jr, Koenigsknecht C, Andreadis ST, Swartz DD. Successful endothelialization and remodeling of a cell-free small-diameter arterial graft in a large animal model. Biomaterials. 2016;76:344–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piterina AV, Cloonan AJ, Meaney CL, Davis LM, Callanan A, Walsh MT, et al. ECM-based materials in cardiovascular applications: Inherent healing potential and augmentation of native regenerative processes. International journal of molecular sciences. 2009;10:4375–417. doi: 10.3390/ijms10104375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polverini PJ, Leibovich SJ. Induction of neovascularization and nonlymphoid mesenchymal cell proliferation by macrophage cell lines. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1985;37:279–88. doi: 10.1002/jlb.37.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leibovich SJ, Polverini PJ, Shepard HM, Wiseman DM, Shively V, Nuseir N. Macrophage-induced angiogenesis is mediated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1987;329:630–2. doi: 10.1038/329630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.L'Heureux N, McAllister TN, de la Fuente LM. Tissue-engineered blood vessel for adult arterial revascularization. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:1451–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc071536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wystrychowski W, Cierpka L, Zagalski K, Garrido S, Dusserre N, Radochonski S, et al. Case study: first implantation of a frozen, devitalized tissue-engineered vascular graft for urgent hemodialysis access. J Vasc Access. 2011;12:67–70. doi: 10.5301/jva.2011.6360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.L'Heureux N, Germain L, Labbe R, Auger FA. In vitro construction of a human blood vessel from cultured vascular cells: a morphologic study. Journal of vascular surgery. 1993;17:499–509. doi: 10.1067/mva.1993.38251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Nguyen D, Ouyang H, Zhang XH, Chen XM, Zhang K. Inhibition of RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway suppresses the expression of extracellular matrix induced by CTGF or TGF-beta in ARPE-19. International journal of ophthalmology. 2013;6:8–14. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.01.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fazio S, Babaev VR, Murray AB, Hasty AH, Carter KJ, Gleaves LA, et al. Increased atherosclerosis in mice reconstituted with apolipoprotein E null macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:4647–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Getz GS, Reardon CA. Apoprotein E as a lipid transport and signaling protein in the blood, liver, and artery wall. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S156–61. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800058-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian S, Han CY, Chiba T, McMillen TS, Wang SA, Haw A, 3rd, et al. Dietary cholesterol worsens adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and atherosclerosis in obese LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:685–91. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.157685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Getz GS, Reardon CA. Animal models of atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32:1104–15. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Getz GS, Reardon CA. Use of Mouse Models in Atherosclerosis Research. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1339:1–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2929-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curtiss LK, Black AS, Bonnet DJ, Tobias PS. Atherosclerosis induced by endogenous and exogenous toll-like receptor (TLR)1 or TLR6 agonists. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2126–32. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M028431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiomi M, Ito T. The Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbit, its characteristics and history of development: a tribute to the late Dr. Yoshio Watanabe. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Miller C, Swarthout RF, Rao M, Mackman N, Taubman MB. Vascular smooth muscle-derived tissue factor is critical for arterial thrombosis after ferric chloride-induced injury. Blood. 2009;113:705–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King VL, Lin AY, Kristo F, Anderson TJ, Ahluwalia N, Hardy GJ, et al. Interferon-gamma and the interferon-inducible chemokine CXCL10 protect against aneurysm formation and rupture. Circulation. 2009;119:426–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.785949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Borne P, Quax PH, Hoefer IE, Pasterkamp G. The multifaceted functions of CXCL10 in cardiovascular disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:893106. doi: 10.1155/2014/893106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bader M, Zhao Y, Sander M, Lee MA, Bachmann J, Bohm M, et al. Role of tissue renin in the pathophysiology of hypertension in TGR(mREN2)27 rats. Hypertension. 1992;19:681–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okamoto K, Aoki K. Development of a strain of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Japanese circulation journal. 1963;27:282–93. doi: 10.1253/jcj.27.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai Q, Xu M, Yao M, Sun B. Angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonists exert anti-inflammatory effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats. British journal of pharmacology. 2007;152:1042–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahl LK. Effects of chronic excess salt feeding. Induction of self-sustaining hypertension in rats. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1961;114:231–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.114.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattson DL. Infiltrating immune cells in the kidney in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2014;307:F499–508. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00258.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben-Ishay D, Dahl LK. Absence of an exaggerated renal response to acute salt loading in salt-hypertensive rats. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1966;123:304–9. doi: 10.3181/00379727-123-31473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zicha J, Dobesova Z, Kunes J. Relative deficiency of nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation in salt-hypertensive Dahl rats: the possible role of superoxide anions. Journal of hypertension. 2001;19:247–54. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hibino N, Yi T, Duncan DR, Rathore A, Dean E, Naito Y, et al. A critical role for macrophages in neovessel formation and the development of stenosis in tissue-engineered vascular grafts. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:4253–63. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naito Y, Williams-Fritze M, Duncan DR, Church SN, Hibino N, Madri JA, et al. Characterization of the natural history of extracellular matrix production in tissue-engineered vascular grafts during neovessel formation. Cells, tissues, organs. 2012;195:60–72. doi: 10.1159/000331405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roh JD, Sawh-Martinez R, Brennan MP, Jay SM, Devine L, Rao DA, et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts transform into mature blood vessels via an inflammation-mediated process of vascular remodeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:4669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911465107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Row S, Santandreu A, Swartz DD, Andreadis ST. Cell-free vascular grafts: Recent developments and clinical potential. Technology (Singap World Sci) 2017;5:13–20. doi: 10.1142/S2339547817400015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swartz DD, Andreadis ST. Animal models for vascular tissue-engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:916–25. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tutino VM, Liaw N, Spernyak JA, Ionita CN, Siddiqui AH, Kolega J, et al. Assessment of Vascular Geometry for Bilateral Carotid Artery Ligation to Induce Early Basilar Terminus Aneurysmal Remodeling in Rats. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2016;13:82–92. doi: 10.2174/1567202612666151027143149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liaw N, Fox JM, Siddiqui AH, Meng H, Kolega J. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase and superoxide mediate hemodynamic initiation of intracranial aneurysms. PloS one. 2014;9:e101721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metaxa E, Tremmel M, Natarajan SK, Xiang J, Paluch RA, Mandelbaum M, et al. Characterization of critical hemodynamics contributing to aneurysmal remodeling at the basilar terminus in a rabbit model. Stroke. 2010;41:1774–82. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.585992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dolan JM, Sim FJ, Meng H, Kolega J. Endothelial cells express a unique transcriptional profile under very high wall shear stress known to induce expansive arterial remodeling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1109–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simgen A, Ley D, Roth C, Yilmaz U, Korner H, Muhl-Benninghaus R, et al. Evaluation of a newly designed flow diverter for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms in an elastase-induced aneurysm model, in New Zealand white rabbits. Neuroradiology. 2014;56:129–37. doi: 10.1007/s00234-014-1320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bi Y, Zhong H, Xu K, Zhang Z, Qi X, Xia Y, et al. Development of a novel rabbit model of abdominal aortic aneurysm via a combination of periaortic calcium chloride and elastase incubation. PloS one. 2013;8:e68476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyake T, Miyake T, Shimizu H, Morishita R. Inhibition of Aneurysm Progression by Direct Renin Inhibition in a Rabbit Model. Hypertension. 2017;70:1201–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilboa SM, Salemi JL, Nembhard WN, Fixler DE, Correa A. Mortality resulting from congenital heart disease among children and adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Circulation. 2010;122:2254–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.947002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowry RB, Bedard T, Sibbald B, Harder JR, Trevenen C, Horobec V, et al. Congenital heart defects and major structural noncardiac anomalies in Alberta, Canada, 1995–2002. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97:79–86. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schultz AH, Wernovsky G. Late outcomes in patients with surgically treated congenital heart disease. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2005:145–56. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Syedain Z, Reimer J, Lahti M, Berry J, Johnson S, Tranquillo RT. Tissue engineering of acellular vascular grafts capable of somatic growth in young lambs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12951. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Row SKMK, Shahini A, Koenigsknecht C, Andreadis ST, Swartz DD. Development of a Hypertensive Ovine model for the Evaluation of Autologous Vascular Grafts. Annals of Surgery: International. 2017:2.

- 64.Lau DH, Mackenzie L, Rajendram A, Psaltis PJ, Kelly DR, Spyropoulos P, et al. Characterization of cardiac remodeling in a large animal "one-kidney, one-clip" hypertensive model. Blood pressure. 2010;19:119–25. doi: 10.3109/08037050903576767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dahl SL, Kypson AP, Lawson JH, Blum JL, Strader JT, Li Y, et al. Readily available tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:68ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawson JH, Glickman MH, Ilzecki M, Jakimowicz T, Jaroszynski A, Peden EK, et al. Bioengineered human acellular vessels for dialysis access in patients with end-stage renal disease: two phase 2 single-arm trials. Lancet. 2016;387:2026–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00557-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qu Z, Krishnamurthy V, Haller CA, Dorr BM, Marzec UM, Hurst S, et al. Immobilization of actively thromboresistant assemblies on sterile blood-contacting surfaces. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3:30–5. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matafonov A, Leung PY, Gailani AE, Grach SL, Puy C, Cheng Q, et al. Factor XII inhibition reduces thrombus formation in a primate thrombosis model. Blood. 2014;123:1739–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-499111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prichard HL, Manson RJ, DiBernardo L, Niklason LE, Lawson JH, Dahl SL. An early study on the mechanisms that allow tissue-engineered vascular grafts to resist intimal hyperplasia. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2011;4:674–82. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.AHA. Staistical Fact Sheet: Older Americans & Cardiovascular Disease. American stroke Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Minamino T, Komuro I. Vascular cell senescence: contribution to atherosclerosis. Circulation research. 2007;100:15–26. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256837.40544.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]