SUMMARY

Vesicular acidification and trafficking are associated with various cellular processes. However, their pathologic relevance to cancer remains elusive. We identified transmembrane protein 9 (TMEM9) as a vesicular acidification regulator. TMEM9 is highly upregulated in colorectal cancer (CRC). Proteomic and biochemical analyses show that TMEM9 binds to and facilitates assembly of v-ATPase, a vacuolar proton pump, resulting in enhanced vesicular acidification and trafficking. TMEM9-v-ATPase hyperactivates Wnt/β-catenin signaling via lysosomal degradation of APC. Moreover, TMEM9 transactivated by β-catenin functions as a positive feedback regulator of Wnt signaling in CRC. Genetic ablation of TMEM9 inhibits CRC cell proliferation in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo mouse models. Moreover, administration of v-ATPase inhibitors suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis of APC mouse models and human patient-derived xenografts. Our results reveal the unexpected roles of TMEM9-controlled vesicular acidification in hyperactivating Wnt/β-catenin signaling through APC degradation, and propose the blockade of TMEM9-v-ATPase as a viable option for CRC treatment.

Keywords: TMEM9, v-ATPase, ATP6AP2, β-catenin, Wnt, colorectal cancer

INTRODUCTION

Wnt signaling orchestrates development, tissue homeostasis, and tissue regeneration1. However, deregulation of Wnt signaling is highly associated with cancers2. In the absence of Wnt ligand, a protein destruction complex, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Axin, and CK1, phosphorylates β-catenin for ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Conversely, the binding of Wnt ligand to Frizzled receptor and low-density lipoprotein-receptor related protein (LRP5/6) co-receptor triggers the recruitment of Dishevelled (Dvl) and Axin to the plasma membrane1, 3, 4. The ligand-receptor interaction induces the formation of LRP signalosome (phosphorylated LRP6, Frizzled, Dvl, Axin, and GSK3)3. Subsequently, the LRP signalosome inhibits GSK3, which stabilizes the β-catenin protein. Then, stabilized (activated) β-catenin protein is translocated into the nucleus and transactivates its downstream target genes, in association with its nuclear partners, T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (LEF)1, 5. It was also proposed that the sequestration of GSK3 into the multivesicular body (MVB) inhibits cytosolic GSK3 kinase activity and activates β-catenin6. Genetic mutations in the core components of Wnt/β-catenin signaling lead to the initiation of intestinal tumorigenesis7. Accumulating evidence suggests that additional factors complement Wnt signaling activity in colorectal cancer (CRC)8–11. Therefore, beyond genetic mutations in Wnt signaling core components, further layers of Wnt signaling regulation likely contribute to intestinal tumorigenesis.

Vesicular acidification and trafficking play key roles in cell physiology12, 13. However, their contribution to cancer remains unknown. Here, we identified transmembrane protein 9 (TMEM9) as a regulator of vesicular acidification in CRC. We found that TMEM9 promotes vesicular acidification via vacuolar adenosine triphosphatase (v-ATPase). v-ATPase is an ATP-dependent proton pump for intracellular compartment acidification14, 15. v-ATPase is a multisubunit protein complex composed of membrane-bound (V0) subunits (a, c, c’’, d, e, ATP6AP1) and cytosolic (V1) subunits (A-H). The V1 subunits catalyze ATP hydrolysis for proton pump through V0 subunit complex. ATP6AP2 (also known as prorenin receptor), an accessory protein of v-ATPase, was shown to transduce both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signals16–18. Herein, we investigated how deregulated vesicular acidification contributes to CRC.

RESULTS

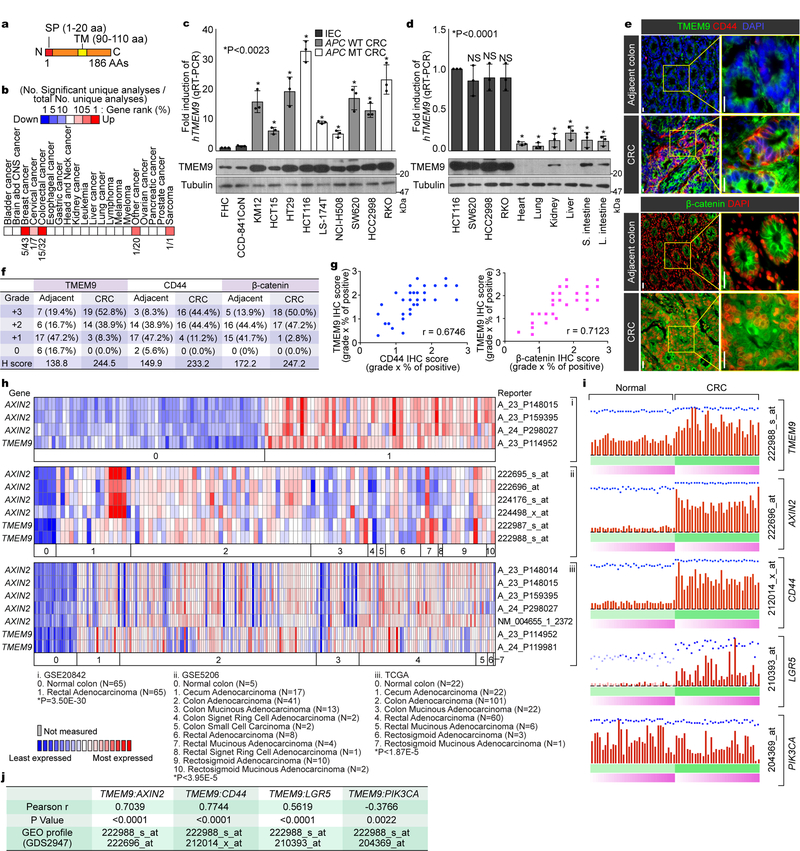

Expression of TMEM9 in CRC

To identify genes playing crucial roles in intestinal tumorigenesis, we analyzed publicly available gene expression data sets, and selected genes highly expressed in CRC compared with normal tissues. We chose TMEM9 as a gene potentially associated with intestinal tumorigenesis. TMEM9 contains a signal peptide (SP) and one transmembrane domain (TMD)(Fig. 1a). Oncomine analysis showed thatTMEM9 was markedly upregulated in CRC and breast cancer (Fig. 1b). TMEM9 is also highly expressed in CRC cells, compared to normal intestinal epithelial cells (IECs)(Fig. 1c). Additionally, quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) assays and immunoblotting (IB) showed that TMEM9 expression in CRC was greatly higher than that in other tissues (Fig. 1d). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of tumor microarrays (TMA) validated the upregulation of TMEM9 in CRC patient samples, while barely expressed in the normal intestinal crypts (Figs. 1e, 1f). Given the pivotal roles of Wnt signaling in CRC, we examined whether TMEM9 is co-expressed with β-catenin and its target gene (CD44)19. IHC results showed the positive correlation of between TMEM9 and both β-catenin and CD44 (Fig. 1g). Moreover, multiple gene expression data sets indicated the upregulation of both TMEM9 and AXIN2 in CRC (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, GDS2947 data sets in Gene Expression Omnibus showed the significant upregulation and positive correlation of TMEM9 and Wnt signaling-associated genes (AXIN2, CD44, LGR5) in CRC, compared to adjacent normal samples (Figs. 1i, 1j). These results suggest that TMEM9 is highly expressed in CRC with hyperactivation of β-catenin and its target genes.

Fig. 1. Expression of TMEM9 in CRC cells.

a, Illustration of the TMEM9 domains. b, In silico analysis of TMEM9 expression in CRC. Oncomine analysis of TMEM9 expression in human cancers (www.oncomine.org). 10% gene rank; p-value<0.0001; fold change>2; compared with normal cells. c, High expression of TMEM9 in CRC. Two IECs and nine CRC cells were collected for IB and qRT-PCR. Tubulin served as a loading control, and TMEM9 expression was normalized by HPRT1. n=3 independent experiments.d, Expression of TMEM9 in mouse tissues. Protein and mRNAs were extracted from six mouse tissues and assessed by IB and qRT-PCR. CRC cells were served as a positive control. n=3 independent experiments e-g, Expression of TMEM29, CD44, and β-catenin in CRC TMA. IHC of TMEM9, CD44, and β-catenin was performed using TMA (Biomax, BC05023; e). H score (f) and Pearson’s correlations (g) were calculated. n=36 biologically independent samples.h, Co-expression of TMEM9 with AXIN2. Oncomine analysis of GSE20842, GSE5206, and TCGA data sets; 10% gene rank; P value<0.0001; fold change>2; compared with normal cells.i and j, Co-expression of TMEM9 with Wnt/β-catenin target genes. GEO data sets (GDS2947) were analyzed for each gene expression in normal intestine and the matched CRC samples (32 patient samples; i). Pearson’s correlations were determined (j).Scale bars=20μm; NS: Not significant. Error bars: mean ± S.D.; Two-sided unpaired t-test.

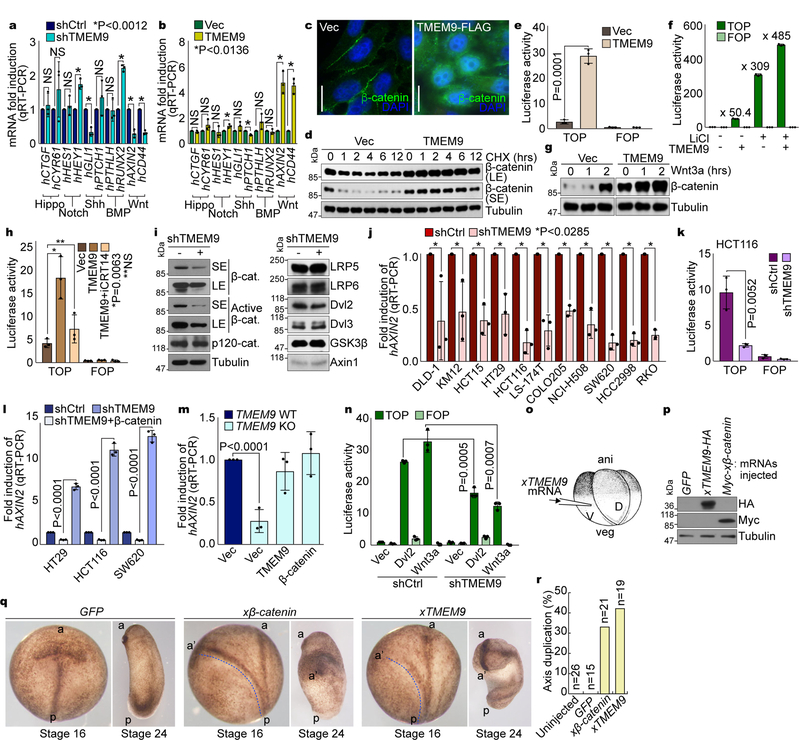

Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by TMEM9 in vitro and in vivo

To understand the pathologic impacts of TMEM9 upregulation to intestinal tumorigenesis, we examined the effects of TMEM9 depletion on CRC-related cellular signaling. HCT116 CRC cells stably expressing shRNAs against TMEM9 displayed the downregulation of Wnt signaling target genes (AXIN2, CD44), while other signaling pathways were barely affected (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figs. 1a, 1b). Conversely, ectopic expression of TMEM9 in IECs upregulated Wnt targets (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1c). These results imply that TMEM9 might be associated with Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which led us to hypothesize that TMEM9 positively modulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. To test this, we analyzed the effects of TMEM9 on the β-catenin protein. Immunofluorescent (IF) staining showed that TMEM9 expression increased both the cytosolic and the nuclear β-catenin (Fig. 2c). Consistently, TMEM9 overexpression increased the half-life of β-catenin protein (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 1d). Additionally, β-catenin reporter (TOPFLASH) and qRT-PCR assays showed that TMEM9 expression per se enhanced β-catenin’s transcriptional activity (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Figs. 1e, 1f). Intriguingly, TMEM9 increased the response of β-catenin reporter activation by LiCl, a GSK3 inhibitor (Fig. 2f). Similarly, TMEM9 also enhanced β-catenin protein stabilization induced by Wnt3a (Fig. 2g). Additionally, iCRT14, an inhibitor of β-catenin-TCF binding, suppressed TMEM9-activated luciferase activity (Fig. 2h). To complement gain-of-function assays, we also utilized shRNAs to deplete endogenous TMEM9 (Supplementary Fig. 1g). Based on the high expression of TMEM9 in CRC cell lines (Figs. 1c, 1d), we used CRC cells for knockdown experiments. TMEM9-depleted HCT116 cells displayed the decrease of β-catenin protein as well as active β-catenin (Fig. 2i). Next, we examined the effects of TMEM9 knockdown on β-catenin’s transcriptional activity. qRT-PCR and β-catenin reporter assays showed that TMEM9 depletion downregulated AXIN2 and β-catenin reporter activity in CRC cells (Figs. 2j, 2k, Supplementary Figs. 1h, 1i). Of note, TMEM9 depletion-induced AXIN2 downregulation was rescued by ectopic expression of β-catenin (Fig. 2l), suggesting that β-catenin mediates the effect of TMEM9 on AXIN2 upregulation. Consistently, similar effects were observed in TMEM9 knockout (KO) HCT116 cells (Fig. 2m, Supplementary Figs. 1j, 1k). Next, to better understand the epistasis of TMEM9 in Wnt signaling, we assessed the effects of TMEM9 depletion on β-catenin-mediated transactivation by Dvl2 and Wnt3a. We found that TMEM9 knockdown diminished both Dvl2- and Wnt3a-induced β-catenin reporter activation (Fig. 2n), implying that TMEM9 might activate Wnt signaling at the same or downstream level of Wnt ligands and Dvls. We also examined the in vivo effects of TMEM9 on Wnt signaling by axis duplication assays using Xenopus laevis embryos. Ectopic activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in ventro-vegetal blastomeres generates a secondary anterior-posterior axis20 (Fig. 2o). We observed that ventro-vegetal microinjection of xTMEM9 or xβ-catenin (positive control) mRNA induced the additional anterior-posterior axis (Figs. 2p-2r). These results suggest that TMEM9 activates Wnt signaling in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 2. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by TMEM9.

a and b, Screening of cell signalings. mRNA expression in CRC cells (a) and IECs (b) was analyzed by qRT-PCR. c-d, Upregulation of β-catenin by TMEM9. IF staining of β-catenin (c). HeLa cells were analyzed for β-catenin protein half-life using cycloheximide (CHX; 100μg/ml; d). e and f, Activation of the β-catenin reporter by TMEM9. CCD-841CoN cells were analyzed by β-catenin reporter assays (e). 293T cells were transfected with each plasmid and treated with LiCl (25mM, 24hr; f). g, Enhancement of β-catenin stabilization by TMEM9 upon Wnt3a. IB of 293T cells transiently expressing Ctrl or TMEM9 upon Wnt3a treatment (200ng/ml). h, Decreased TMEM9-activated β-catenin reporter by iCRT14. 48hr after overexpression of TMEM9, CCD-841CoN cells were incubated with vehicle or iCRT14 (100μM, 12hr). i, Inhibition of β-catenin by TMEM9 depletion. IB of HCT116 (shCtrl vs. shTMEM9). j and k, Decreased β-catenin transcription activity by shTMEM9. qRT-PCR of AXIN2 (j) and luciferase activity (k). l and m, Rescue of Wnt/β-catenin activity by ectopic expression of β-catenin in TMEM9-depleted CRC. CRC cells were transfected with indicated plasmids for 24hr (l). HCT116 (TMEM9 WT vs. KO) cells were stably transduced with either TMEM9 or β-catenin (m). n, Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation by TMEM9 at the downstream of Dvl2 and Wnt3a. HCT116 cells were co-transfected with β-catenin reporter plasmids and Dvl2 or treated with Wnt3a for luciferase assays. o-r, In vivo activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by xTMEM9 in frog embryos. Xenopus laevis embryos were injected with each mRNA into ventral-vegetal blastomeres at the 4-cell stage (o). Expression of microinjected Myc-xβ-catenin or xTMEM9-HA mRNA was confirmed by IB (p). Axis duplication was analyzed at the neural fold (st16) and the tail buds (st24) stages (q). Quantification of axis duplication (r). ani: animal pole; veg: vegetal pole; V: ventral region; D: dorsal region; a: anterior; p: posterior; a’: secondary anterior axis. n: biologically independent samples. Experiment was performed once. Images in c and blots in d, g, I and p are representative of three independent experiments with similar results; Scale bars=20μm; NS: Not significant; Error bars: mean ± S.D.; Two-sided unpaired t-test.

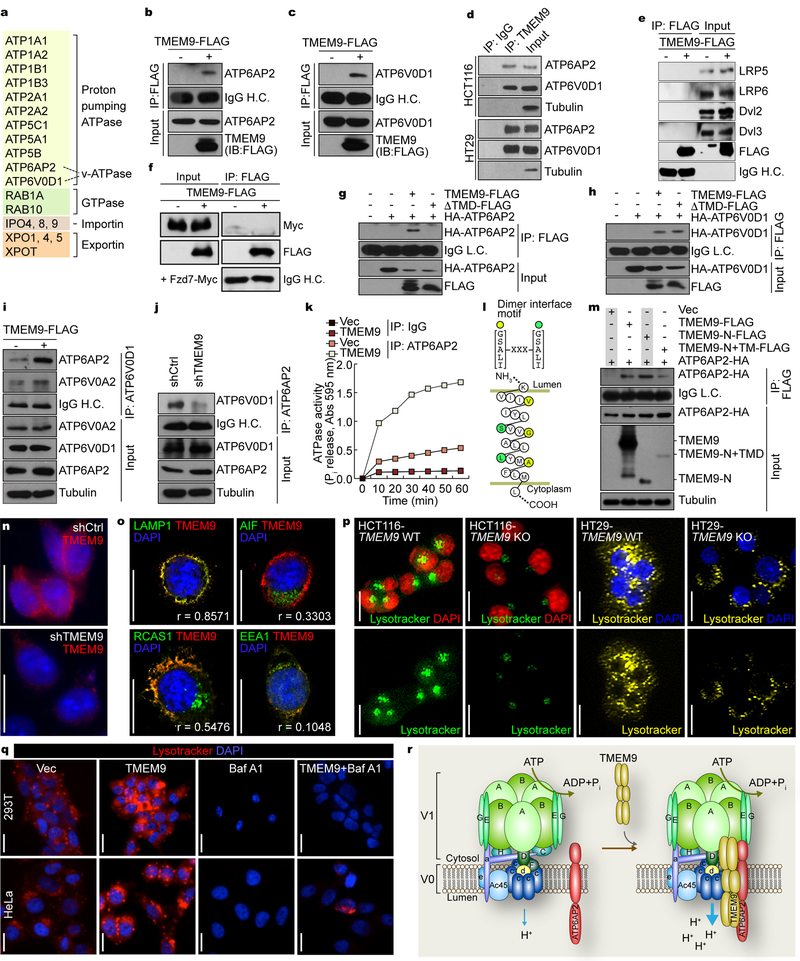

TMEM9 Binds and Activates v-ATPase by Promoting v-ATPase-ATP6AP2 Assembly

To elucidate the molecular mechanism of TMEM9-activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we sought to identify TMEM9-interacting proteins using tandem-affinity protein purification and mass spectrometry analysis (TAP-MS/MS)(Fig. 3a). Interestingly, we identified that TMEM9 was highly associated with the v-ATPase protein components: ATP6AP2, a v-ATPase accessory protein, and ATP6V0D1, a rotary subunit mediating V0-V1 coupling14. ATP6AP2 was previously shown to connect the LRP signalosome to v-ATPase16. Thus, we hypothesized that TMEM9 modulates v-ATPase activity through physical interaction with v-ATPase and ATP6AP2. Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays confirmed that TMEM9 bound to both ATP6AP2 and ATP6V0D1 in 293T (Figs. 3b, 3c) and CRC cells (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 2a). However, unlike the previous study16, TMEM9 did not bind to LRP signalosome components (Figs. 3e, 3f), consistent with our proteomic analysis (Fig. 3a). Based on TMEM9’s SP and TMD, we also tested whether TMEM9’s membrane targeting is required for interaction with either ATP6V0D1 or ATP6AP2. Co-IP for either wild-type (WT) or a ΔTMD mutant (MT) of TMEM9 showed that TMEM9’s TMD is essential for interacting with ATP6AP2 (Fig. 3g), but not with ATP6V0D1 (Fig. 3h). ATP6V0D1 functions as a central stalk that regulates v-ATPase assembly21. Additionally, ATP6AP2 is indispensable for v-ATPase assembly22. Thus, modulating the interaction between ATP6AP2 and v-ATPase might affect the activity of v-ATPase. To test this, we asked whether TMEM9 promotes v-ATPase assembly. Co-IP assays showed that TMEM9 expression enhanced ATP6AP2-ATP6V0D1 interaction in 293T cells (Fig. 3i). Conversely, TMEM9 depletion decreased ATP6AP2-ATP6V0D1 binding in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3j). Next, we assessed the effects of TMEM9 on v-ATPase activity. We performed co-IP experiments using ATP6AP2 antibody in HeLa (Control vector [Vec] vs. TMEM9 expressing) cells and quantified ATP6AP2-associated ATPase activity by measuring inorganic phosphate (Pi) released by ATP hydrolysis. Co-immunoprecipitates of ATP6AP2 from HeLa-TMEM9 displayed the markedly increased level of Pi upon ATP addition, compared with those from control (Fig. 3k). These results suggest that TMEM9 positively modulates v-ATPase activity. Additionally, amino acid sequence analysis located a dimerization motif ([G/S/A/L/I]-XXX-[G/S/A/L/I])23 in the TMD of TMEM9 (Fig. 3l). Co-IP assays showed that different epitope-tagged TMEM9 proteins bound to each other, implying the potential oligomerization of TMEM9 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Also, binding domain-mapping analysis suggests that the N-terminus of TMEM9 is required for binding to ATP6AP2 (Fig. 3m).

Fig. 3. TMEM9 facilitates assembly of v-ATPase.

a, Identification of TMEM9-interacting proteins. 293T cells stably expressing TMEM9 were processed for TAP-MS/MS. Experiment was performed once. b and c, Interaction of TMEM9 with v-ATPase components, ATP6AP2 (b) and ATP6V0D1 (c). 293T cells were transfected with each plasmid and analyzed for co-IP. d, Endogenous binding of TMEM9 to ATP6AP2 and APT6V0D1. Co-IP of HCT116 and HT29. e and f, No interaction of TMEM9 with LRPs, Dvls, and Fzd. Co-IP of 293T cells transfected with TMEM9-FLAG plasmids (e), or co-transfected with TMEM9-FLAG and Fzd7-Myc plasmids (f). g and h, Requirement of TMEM9-TMD for binding to ATP6AP2 but not ATP6V0D1. 293T cells were transfected with each plasmid and analyzed by co-IP. i, Increased ATP6AP2-ATP6V0D1 binding by TMEM9. 293T stable cells (Ctrl vs. TMEM9) were analyzed by co-IP. j, Decreased ATPAP2-ATP6V0D1 binding by TMEM9 depletion. HCT116 stable cells (shCtrl vs. shTMEM9) were analyzed by co-IP.k, Upregulation of ATP6AP2-associated ATPase activity by TMEM9. HeLa cells were immunoprecipitated using ATP6AP2 antibody. Then, the immunoprecipitates were analyzed for ATPase activity. Experiment was performed twice with similar results (n=3 each independent samples).l, Illustration of TMD of TMEM9 using TOPO2 (http://www.sacs.ucsf.edu/cgi-bin/open-topo2.py). m, Binding of ATP6AP2 to N-terminus of TMEM9. 293T cells were transfected with each TMEM9 mutant plasmid and analyzed by co-IP. n, Subcellular localization of endogenous TMEM9. IF staining of HCT116 (shCtrl vs. shTMEM9). o, Localization of TMEM9 in the MVBs. Co-IF staining of TMEM9 with organelle markers in HCT116 cells. AIF (mitochondria); EEA1 (early endosome); LAMP1 (MVB); RCAS1 (Golgi complex). Quantification of colocalization was performed using the ImageJ. r=colocalization coefficient (n=8 independent experiments). p, Downregulation of MVB acidification by TMEM9 KO in vitro. HCT116 and HT29 (TMEM9 WT vs. KO) cells were stained with Lysotracker (30min).q, TMEM9-induced vesicle acidification via v-ATPase. 293T and HeLa cells stably expressing Ctrl vector or TMEM9 were treated with BAF (10nM, 24hr), and stained with Lysotracker. r, Schematic illustration of TMEM9-induced activation of v-ATPase. TMEM9 promotes interaction between v-ATPase and ATP6AP2, which leads to activation of v-ATPase. V1: cytosolic units hydrolyzing ATP; V0: membrane-bound subunits. Representative images of three experiments with similar results (blots of b-j and m; images of n-q); Scale bars=20μm.

TMEM9 contains an SP and one α-helix TMD (Fig. 1a), implying its possible localization to membranous organelles and/or the plasma membrane. IF staining showed that both endogenous and exogenous TMEM9 localized to the cytoplasm and the perinucleus with a speckled pattern in HCT116 and HeLa cells (Fig. 3n, Supplementary Fig. 2c), consistent with the results from CRC tissue immunostaining (Fig. 1e). Co-IF showed that TMEM9 mainly colocalized with LAMP1, a marker for the MVB (Fig. 3o). The lower pH in the lumen of membranous organelles is maintained by v-ATPase-mediated proton efflux. Given the subcellular localization of TMEM9 in the MVB (Fig. 3o) and TMEM9-activated v-ATPase (Fig. 3k), we tested whether TMEM9 increases the intracellular vesicle acidification, using Lysotracker, a marker for acidic organelles. Depletion of TMEM9 significantly decreased vesicle acidification (Fig. 3p, Supplementary Fig. 2d), while TMEM9 expression increased it (Fig. 3q, Supplementary Fig. 2e). To validate the effects of TMEM9 on vesicular acidification, we utilized Bafilomycin A1 (BAF), an inhibitor of v-ATPase24. BAF inhibited TMEM9-induced vesicular acidification (Fig. 3q). These results suggest that TMEM9 binds to ATP6AP2 and v-ATPase, and increases v-ATPase activity, which results in the vesicular acidification (Fig. 3r).

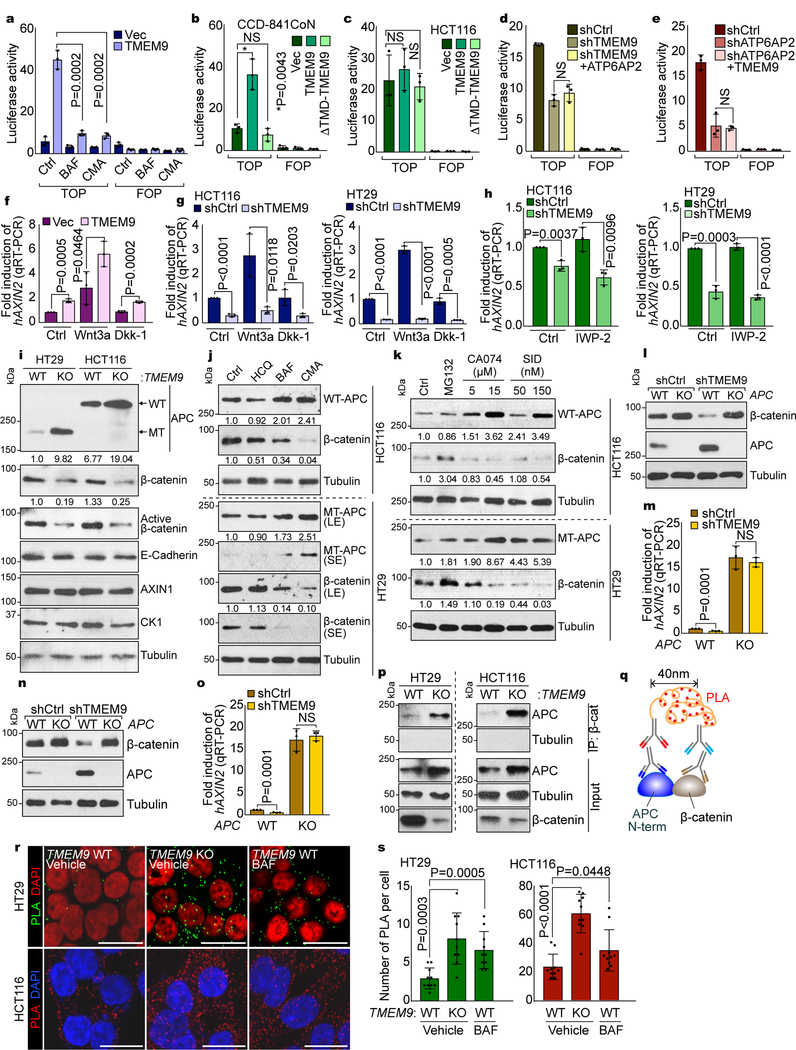

Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by TMEM9-v-ATPase-Mediated APC Degradation

We next questioned whether v-ATPase is required for TMEM9-induced Wnt signaling activation. Recent studies have proposed a crucial role of the MVBs in transducing Wnt signaling3, 16. Given (1) the localization of TMEM9 to MVBs (Fig. 3o), (2) co-expression of TMEM9 with β-catenin target genes in CRC (Figs. 1e-1j), (3) TMEM9-activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 2), and (4) TMEM9-enhanced v-ATPase activity (Fig. 3), we hypothesized that TMEM9-induced vesicular acidification activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. We found that the blockade of v-ATPase using BAF suppressed TMEM9-induced β-catenin protein stabilization (Supplementary Figs. 3a, 3b). Additionally, TMEM9-activated β-catenin reporter was suppressed by BAF or Concanamycin A (CMA), another v-ATPase inhibitor24 (Fig. 4a). Additionally, ΔTMD-TMEM9 was unable to activate β-catenin reporter activity (Figs. 4b, 4c, Supplementary Figs. 3c, 3d), indicating that TMEM9’s membrane targeting is necessary for Wnt signaling activation. We also observed that ATP6AP2 depletion inhibited TMEM9-induced Wnt signaling activation (Supplementary Figs. 3e, 3f), suggesting that ATP6AP2 is required for TMEM9-activated Wnt signaling. We further tested whether TMEM9 and ATP6AP2 are reciprocally dependent in activating Wnt signaling. TMEM9 depletion-reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity was not restored by ATP6AP2 and vice versa (Figs. 4d, 4e, Supplementary Figs. 3g, 3h), unlike β-catenin, a positive control (Supplementary Figs. 3i, 3j).

Fig. 4. Decrease of APC by TMEM9-induced v-ATPase activation.

a, Suppression of TMEM9-activated β-catenin reporter by v-ATPase inhibitors. 239T cells were transfected with β-catenin reporter plasmids and treated with BAF or CMA for 24hr. b and c, Requirement of TMEM9-TMD for TMEM9-induced β-catenin reporter activation. CCD-841CoN (b) and HCT116 (c) cells were transfected with indicated plasmids and analyzed by luciferase assays. d and e, No effect of ATP6AP2 and TMEM9 on β-catenin reporter activity in TMEM9- or ATP6AP2-depleted CRC cells, respectively. shCtrl, shTMEM9 (d), or shATP6AP2 (e) plasmids were co-transfected with ATP6AP2 (d) or TMEM9 (e) plasmids, respectively. f and g, Increased β-catenin transcription activity by TMEM9 independently of Wnt agonist or antagonist. IECs (f) and CRC cells (g) were incubated with Wnt3a (50ng/ml) or Dkk-1 (100ng/ml) for 12hr and analyzed by AXIN2 qRT-PCR.h, Downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by shTMEM9 independently of Wnt ligand secretion. After transfection, cells were incubated with IWP-2 (2μM) for 12hr. qRT-PCR of AXIN2. i, Upregulated APC protein by TMEM9 depletion. TMEM9 WT and KO cells were analyzed by IB. j, Increased APC protein by v-ATPase inhibition. HCT116 and HT29 cells were incubated with indicated reagents (HCQ: 25μM; BAF: 3nM; CMA: 0.3nM) for 6hr. IB analysis and quantification using ImageJ.k, APC upregulation by the inhibition of lysosomal protein degradation. CRC cells were incubated with Cathepsin inhibitors (CA074 and SID26681509) for 12hr. IB and quantification using ImageJ. l-o, Loss of TMEM9 depletion-downregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling by APC KO. HCT116 (l and m) and HT29 (n and o) cells were analyzed for IB and qRT-PCR of AXIN2. p-s, The increased interaction between APC and β-catenin by TMEM9 KO. Co-IP analysis (p). Scheme of Duolink assay monitoring APC-β-catenin binding (q). Cells were incubated with APC-N terminal (mouse) and β-catenin (rabbit) antibody followed by reaction with PLA probes. Dots indicate an interaction between APC and β-catenin (r). Protein interaction was quantified (s; n=10 independent samples) using manufacturer’s software (Sigma). Representative images of three experiments with similar results; Scale bars=20μm; NS: Not significant; Error bars: mean ± S.D. from n=3 independent experiments, except from s; Two-sided unpaired t-test.

MVB acidification activates FZD/LRP6-dependent Wnt/β-catenin signaling16. Thus, we tested whether TMEM9 affects FZD/LRP6-mediated Wnt signaling activation. We found that TMEM9-activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling was not affected by Dkk-1, a Wnt antagonist (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 3k). Moreover, TMEM9 depletion inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling, independently of Wnt3a (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 3l). Although it was proposed that MVB increases the secretion of Wnt ligands25, 26, TMEM9-depletion downregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling was not affected porcupine inhibitor, IWP-2 (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 3m).

It was recently shown that mutant APC still induces the β-catenin degradation10. Having determined that TMEM9 depletion inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling regardless of APC mutation (Figs. 2j, 2k, Supplementary Figs. 1h, 1i), we tested whether TMEM9-induced MVB acidification alters APC protein level. Interestingly, TMEM9 KO and shTMEM9 cells showed the increase of APC protein (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Fig. 3n). v-ATPase inhibitors also increased APC protein with the decreased β-catenin in both HCT116 (APC WT; 2,843 amino acids) and HT29 (APC MT; 1,555 amino acids)10, 27 cells, while hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an inhibitor of autophagy, did not (Fig. 4j). Vesicular acidification is indispensable for lysosomal protein degradation28. Thus, we determined whether lysosomal protein degradation mediates TMEM9 depletion-increased APC protein. We found that inhibition of Cathepsin, a lysosomal protease, increased both WT and MT APC protein along with the decreased β-catenin (Fig. 4k). Next, we asked whether APC mediates TMEM9 depletion-induced β-catenin downregulation using APC KO cells. shTMEM9 showed no decrease of β-catenin protein and AXIN2 expression in APC KO-HCT116 and -HT29 cells (Figs. 4l-4o). We also found that β-catenin bound to both WT and MT APC, which was increased by TMEM9 KO (Figs. 4p-4s). Similarly, BAF also increased APC-β-catenin interaction (Figs. 4r, 4s). These results suggest that TMEM9-v-ATPase axis activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling by lysosomal degradation of APC.

Transactivation of TMEM9 by β-catenin

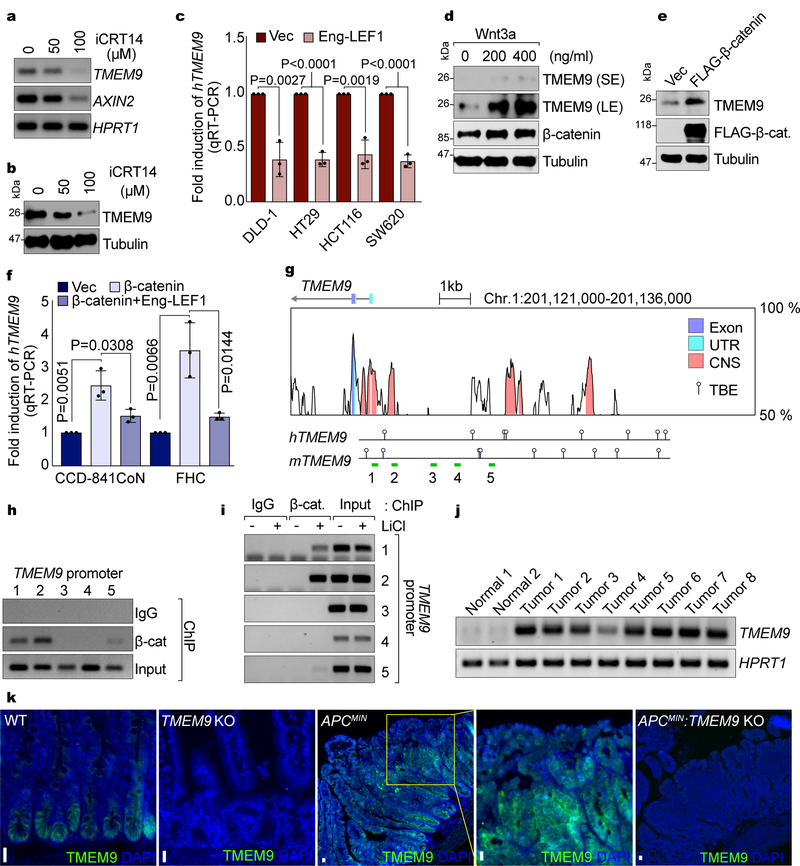

Next, we sought to understand how TMEM9 is upregulated in CRC. Having observed the co-expression of TMEM9 with β-catenin targets in CRC (Figs. 1e-1j), we tested whether Wnt/β-catenin signaling upregulates TMEM9 in CRC. Interestingly, iCRT14-treated HCT116 exhibited downregulation of TMEM9 transcripts (Fig. 5a) and protein (Fig. 5b). Similarly, Engrailed-∆N-LEF1 (Eng-LEF1), a dominant-negative MT for β-catenin-mediated transcription29, also downregulated TMEM9 (Fig. 5c). Conversely, Wnt3a upregulated TMEM9 in 293T cells (Fig. 5d). Additionally, β-catenin ectopic expression upregulated TMEM9 (Figs. 5e, 5f), which was inhibited by Eng-LEF1 (Fig. 5f). In silico analysis identified the potential TCF/LEFs binding elements (TBEs; CTTTGA/TA/T) in conserved non-coding sequences (CNS) between human and mouse TMEM9 promoter (Fig. 5g), which led us to test whether β-catenin directly transactivates TMEM9 using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. ChIP for endogenous β-catenin showed that β-catenin occupied the proximal promoter of TMEM9 in HCT116 cells (Fig. 5h). Given that TMEM9 is upregulated by Wnt signaling activation (Figs. 5d-5f), we also asked whether β-catenin conditionally occupies TMEM9 promoter, upon Wnt signaling activation. Indeed, in the setting of treatment of LiCl, β-catenin occupied the TMEM9 promoter (Fig. 5i). Next, we examined whether β-catenin upregulates TMEM9 in vivo. Both TMEM9 mRNA and protein levels were highly increased in intestinal adenomas of APCMIN mice (Figs. 5j, 5k). These results suggest that β-catenin directly transactivates TMEM9 in CRC.

Fig. 5. Transactivation of TMEM9 by Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling.

a and b, Downregulation of TMEM9 by β-catenin inhibition. HCT116 cells were treated with iCRT14 for 24hr and analyzed by RT-PCR (a) and IB (b). c, Increased TMEM9 expression by β-catenin in CRC. After inhibition of β-catenin transcription activity by Eng-LEF1, TMEM9 expression was assessed by qRT-PCR. n=3 independent experiments. Error bars: mean ± S.D.; Two-sided unpaired t-test. d, Upregulation of TMEM9 by Wnt3a. 293T cells were treated with Wnt3a and analyzed by IB. e, Increased TMEM9 by β-catenin. 293T cells were transfected with β-catenin-expressing plasmids and analyzed by IB, 48hr after transfection. f, Increase of TMEM9 expression by β-catenin in IECs. IECs were transfected with Vec, β-catenin, or Eng-LEF1 plasmids for 48hr. Cells were harvested for qRT-PCR of TMEM9. n=3 independent experiments. Error bars: mean ± S.D.; Two-sided unpaired t-test.g, TMEM9 promoter analysis using VISTA genome browser. UTR: untranslated region; CNS: conserved non-coding sequence; TBE: TCF binding elements (balloons); green bars: PCR amplicons (1~5). h, β-catenin occupancy on the TMEM9 promoter. HCT116 cells were analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. i, Conditional recruitment of β-catenin on the TMEM9 promoter. HeLa cells were treated with LiCl (25mM, 4hr) and analyzed by ChIP assays. j and k, Upregulation of TMEM9 in APCMIN intestinal tumors. TMEM9 expression was examined in two normal small intestinal samples and eight intestinal adenoma samples (1~8) from APCMIN mouse (14 weeks of age) by RT-PCR (j) and IHC (k). TMEM9 KO mice served as negative controls (TMEM9−/− and APCMIN:TMEM9−/−).Representative images of three experiments with similar results; Scale bars=20μm.

Suppression of Intestinal Tumorigenesis by TMEM9 blockade

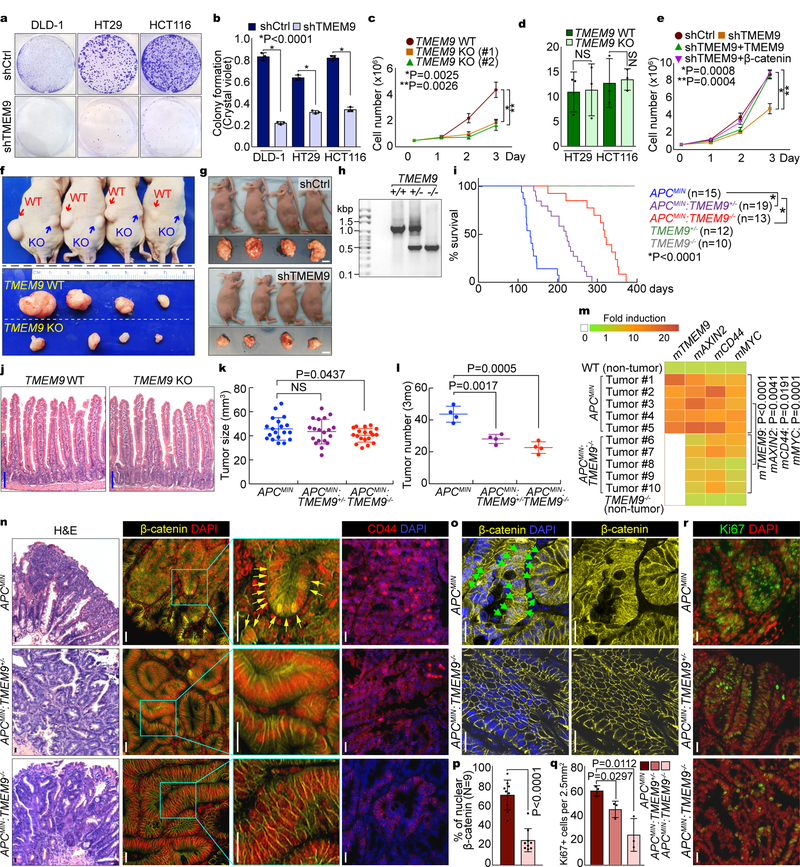

Our results showed (1) specific upregulation of TMEM9 in CRC and (2) TMEM9-activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Moreover, the Kaplan–Meier plot of human CRC showed the lower survival with high expression of TMEM9 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). These data prompted us to hypothesize that TMEM9 plays key roles in intestinal tumorigenesis. To test this, we assessed the effects of TMEM9 depletion on CRC cell proliferation (shCtrl vs. shTMEM9). We found that TMEM9-depleted CRC cells displayed the decreased cell growth (Figs. 6a-6c, Supplementary Figs. 4b, 4c) without a change in cell death (Fig. 6d), which was rescued by β-catenin expression (Fig. 6e). These results suggest that β-catenin mediates TMEM9’s mitogenic effect on CRC cells.

Fig. 6. Suppression of intestinal tumorigenesis by blockade of TMEM9.

a-c, Decreased CRC cell proliferation by TMEM9 depletion. Crystal violet staining (a) was quantified by absorbance at 590nm (b). HCT116 cell proliferation was analyzed by cell counting (c). Two different gRNAs (#1 and #2) were used for CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of TMEM9 alleles. d, No effects of TMEM9 KO on cell death. Trypan blue positive cells were quantified. e, Rescue of TMEM9 depletion-induced cell growth inhibition by TMEM9 or β-catenin. HCT116 (shCtrl and shTMEM9) cells were stably transduced with TMEM9 or β-catenin and analyzed by cell counting. f and g, Reduced CRC cell proliferation by TMEM9 depletion ex vivo. Each mouse (n=4 biologically independent samples) was subcutaneously injected with 1×107 cells into the left (HT29 [Ctrl]) and the right flanks (TMEM9 KO-HT29; f). 15 days after transplantation, tumors were harvested. HCT116 (shCtrl and shTMEM9) cells were subcutaneously injected into immunocompromised mice (g). Scale bars=1cm. Experiments were performed once. h, PCR genotyping results of TMEM9 KO. i, Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier analysis) of APCMIN, APCMIN:TMEM9+/−, and APCMIN:TMEM9−/− mice. j, No defects in IEC differentiation by TMEM9 KO. H&E (Hematoxylin & Eosin). Scale bars=100μm. k and l, Decreased tumor growth by TMEM9 KO. Tumor size (k; n=19 independent samples) and tumor number (l; n=4 biologically independent samples) were quantified by measuring intestinal adenomas in APCMIN, APCMIN:TMEM9+/−, and APCMIN:TMEM9−/− mice (3mo of age). Experiments were performed once. m, Downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin target genes by TMEM9 KO in APCMIN adenomas. APCMIN- and APCMIN:TMEM9 KO-induced tumors and IECs of WT and TMEM9 KO were collected for qRT-PCR of β-catenin target genes (AXIN2, CD44, and MYC) and TMEM9. n, IHC analysis of intestinal tumors from APCMIN, APCMIN:TMEM9+/−, and APCMIN:TMEM9−/− mice. Scale bars=20μm. o and p, Loss of nuclear β-catenin by TMEM9 KO in APCMIN mice. APCMIN- and APCMIN:TMEM9 KO-induced tumors were stained with β-catenin antibody (o) and quantified (n=9 independent tumors; p). Scale bars=20μm. q and r, IHC for Ki67 (r) and quantification of Ki67 positive (Ki67+) cells from intestinal tumors (q; n=3 independent tumors). Scale bars=20μm. Representative images and blots of three experiments with similar results (panels a-e, j, and m-r); Error bars: mean ± S.D. Two-sided unpaired t-test. NS: Not significant.

To gain further insights into the tumorigenic roles of TMEM9 in more physiologic settings, we subcutaneously injected TMEM9-depleted CRC cells into immunocompromised mice and analyzed for tumor formation. TMEM9-depleted CRC cells developed smaller tumors (Figs. 6f, 6g, Supplementary Figs. 4d, 4e) with decreased cell proliferation (Ki67) and downregulated CD44 (Supplementary Fig. 4f).

To complement ex vivo results, we established the TMEM9 KO mice (Fig. 6h, Supplementary Fig. 4g). TMEM9 KO mice were viable without any apparent phenotype (Figs. 6i, 6j, Supplementary Fig. 4h). To determine whether TMEM9 KO suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis, we generated APCMIN:TMEM9−/− compound strains. APCMIN mice die with multiple adenomas in the small intestine30. While the median survival of APCMIN mice was 124 days of age, that of APCMIN:TMEM9−/− mice was 323 days. Of note, heterozygous KO of TMEM9 (APCMIN:TMEM9+/−) was also sufficient to increase survival (median survival: 199 days; Fig. 6i, Supplementary Fig. 4i). Additionally, we monitored the tumor size and number in the APCMIN-, APCMIN:TMEM9+/−-, and APCMIN:TMEM9−/−-induced tumors at 3 months (mo) of age. Although TMEM9 KO slightly decreased tumor size (Fig. 6k), tumor number was significantly reduced, compared to TMEM9 WT (Fig. 6l). qRT-PCR and IHC analyses showed the decreased transcriptional activity (Fig. 6m) and protein level of β-catenin (Figs. 6n, 6o), the diminished β-catenin target expression (Cyclin D1, CD44; Fig. 6n, Supplementary Fig. 4j), and the reduced cell proliferation (Figs. 6q, 6r), compared to those of APCMIN mice. Of note, the number of nuclear β-catenin positive cells in tumors was decreased in APCMIN:TMEM9−/− mice (Figs. 6o, 6p) without significant difference in apoptosis (c-Cas3; Supplementary Fig. 4k) and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT; Supplementary Figs. 4l, 4m). These results strongly suggest that genetic ablation of TMEM9 suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis ex vivo and in vivo.

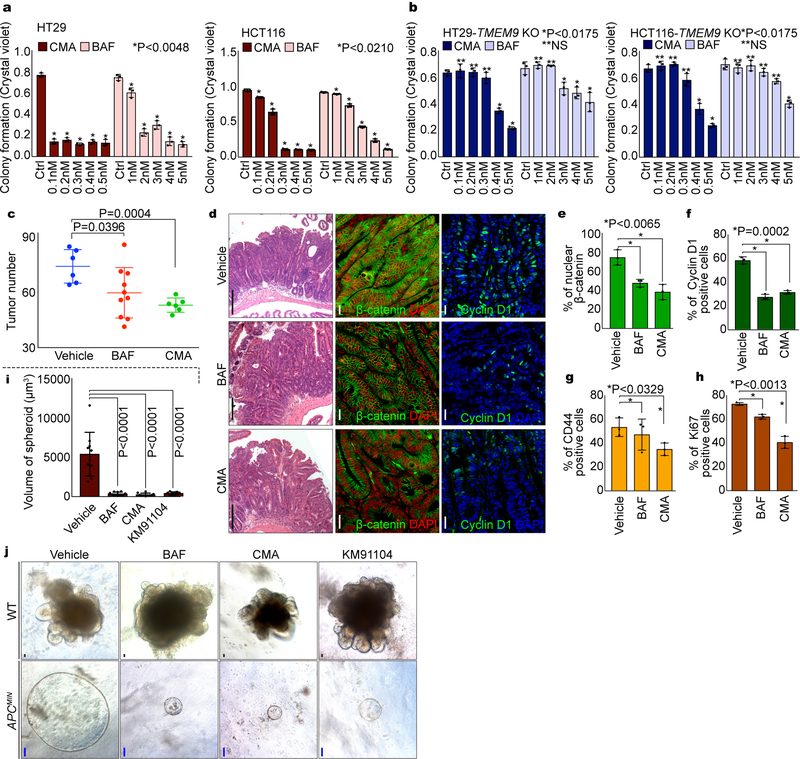

Inhibition of Intestinal Tumorigenesis by v-ATPase inhibitors

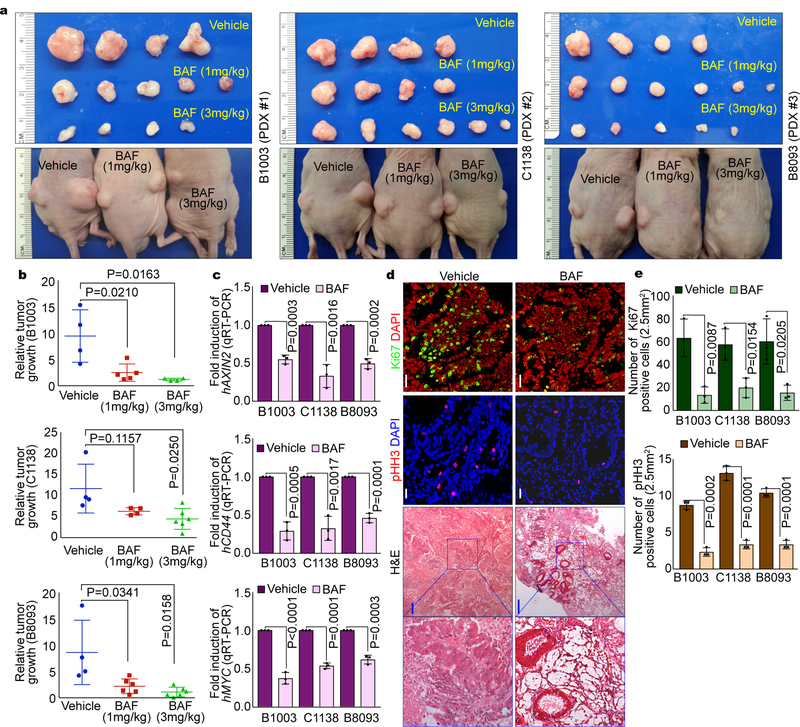

Having determined that TMEM9 activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling via v-ATPase, we next asked whether v-ATPase inhibitors suppress intestinal tumorigenesis. First, we assessed the impacts of v-ATPase inhibitors to CRC cell growth. Indeed, BAF and CMA significantly inhibited the CRC cell proliferation (HT29, HCT116; Fig. 7a). Of note, the impact of v-ATPase inhibitors to CRC cell growth suppression was diminished in TMEM9 KO CRC cells (Fig. 7b), compared to TMEM9 WT cells (Fig. 7a). We also examined the effect of v-ATPase inhibitors on CRC using the APCMIN mouse model. While the normal intestinal homeostasis was not affected by v-ATPase inhibitors, APCMIN mice-treated with BAF or CMA exhibited the decrease in intestinal adenoma number, β-catenin, β-catenin targets, and tumor cell proliferation (Figs. 7c-7h, Supplementary Figs. 5a, 5b), compared to the vehicle-treated control mice. Similarly, intestinal tumor organoids-treated with v-ATPase inhibitors also showed the decreased tumor growth whereas the normal crypt organoids exhibited no impairment in the growth and expansion (Figs. 7i, 7j). These results led us to further test the impacts of v-ATPase inhibitors on human CRC employing PDX models. Similar to mouse results, BAF decreased PDX growth (Figs. 8a, 8b, Supplementary Figs. 6a, 6b, Supplementary Table 2) with the reduced β-catenin and target expression (Fig. 8c) and cell proliferation (Ki67, pHH3; Figs. 8d, 8e, Supplementary Fig. 6c). Additionally, BAF-treated PDXs exhibited the increase of APC and the decrease of nuclear β-catenin (Supplementary Figs. 6d, 6e). These results strongly suggest that the blockade of v-ATPase suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis with the reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity.

Fig. 7. Suppression of intestinal tumorigenesis by v-ATPase inhibitors.

a, Suppressed CRC cell proliferation by v-ATPase inhibitors. CRC cells (1,000 cells) were seeded and treated with v-ATPase inhibitors for 10 days. Then, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After fixation, cells were stained with crystal violet. Cell proliferation was quantified by measuring absorbance at 590nm. n=3 independent experiments. b, Diminished effects of v-ATPase inhibitors on CRC cell growth by TMEM9 KO. TMEM9 KO-HT29 and -HCT116 cells (1,000 cells) were incubated with CMA or BAF for 10 days. Quantification of crystal violet staining. n=3 independent experiments.c, Decrease of APCMIN-induced tumorigenesis by v-ATPase inhibitors. APCMIN mice (10 weeks of age) were injected with BAF (3mg/kg; n=10 biologically independent samples) or CMA (1mg/kg; n=6 biologically independent samples) every 3 days for 6 weeks. Experiments were performed once. d-h, Downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by v-ATPase inhibitors. After administration of v-ATPase inhibitors every (3 days for 6 weeks), APCMIN-induced tumors were stained by H&E (d), β-catenin (d), CD44 (d), Cyclin D1 (d), and Ki67 (d) antibody and quantified (e-h). White scale bars=20μm. Black scale bars=200μm. n=3 independent experiments. i and j, Growth inhibition of tumor but not crypt organoids by v-ATPase inhibitors. Organoids were derived from the intestinal crypts or tumors of WT C57BL/B6 and APCMIN mice (j), respectively. 14 days after incubation with v-ATPase inhibitors, organoid growth was assessed (i). Black scale bars=20μm. Blue scale bars=100μm. n=10 independent samples. Representative images of three experiments with similar results; Error bars: mean ± S.D.; Two-sided unpaired t-test.

Fig. 8. Decreased PDX growth by v-ATPase inhibitor.

a and b, Suppression of PDX growth by BAF. Immunocompromised mice (BALB/c nude) were subcutaneously transplanted with three PDXs into both right and left flanks. 7 days after transplantation, mice were injected with vehicle (corn oil; n=4 biologically independent samples) or BAF (1mg/kg [B1003; n=5 biologically independent samples, C1138; n=4 biologically independent samples, B8093; n=6 biologically independent samples] or 3mg/kg [B1003; n=4 biologically independent samples, C1138; n=6 biologically independent samples, B8093; n=5 biologically independent samples]) every 3 days for 15 days (a). At 18 days post injection, PDXs were collected for assessment of relative tumor growth (ratio of weight [day18/day0]; b). Experiments were performed once. c, Downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by BAF in PDX model. qRT-PCR of β-catenin target genes (hAXIN2, hCD44, and hMYC). n=3 independent experiments.d and e, Decreased cell proliferation by BAF in PDXs. IHC for phosphorylated-Histone H3 (pHH3; a marker of mitosis) and Ki67 (a marker of proliferative cells), and H&E (d), and quantification (e). White scale bars=20μm. Blue scale bars=200μm. n=3 independent experiments. Representative images of three experiments with similar results.Error bars: mean ± S.D.; Two-sided unpaired t-test.

DISCUSSION

Several regulatory mechanisms of v-ATPase activity have been proposed. For instance, the v-ATPase assembly is reversible31, 32 and controlled by E3 ligase33. TMEM9 is mainly localized in the MVBs and interacts with several components of proton pump and their accessory proteins, ATP6AP2 and v-ATPase. We found that TMEM9 increases ATP6AP2-ATP6V0D1 interaction. Given (1) the interaction of TMEM9 with both ATP6AP2 and ATP6V0D1 and (2) the relatively small size of TMEM9 (186 amino acids), it is likely that TMEM9 acts as a molecular adaptor modulating interaction between ATP6AP2 and ATP6V0D1. Unlike TMEM9, other v-ATPase components (ATP6AP2, ATP6V0D1, TMEM9B, [a homologous gene of TMEM9]) are not upregulated in human CRC (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Thus, hyperactivation of v-ATPase in CRC might be mainly due to upregulation of TMEM9. It was previously shown that ATP6AP2 binds to LRPs and Fzd to promote Wnt signals16. However, our mass spectrometry and co-IP results did not detect LRP signalosome components as TMEM9 interacting proteins (Figs. 3a, 3e, 3f), implying that TMEM9-activated Wnt signaling in CRC might be somewhat distinct from ATP6AP2-LRP-Fzd-mediated Wnt signaling activation.

Despite frequent mutations in APC (~70%)2, accumulating evidence suggests that additional intrinsic and extrinsic factors may further hyperactivate Wnt signaling during tumor initiation and metastasis9–11, 34. It was also shown that mutant APC still negatively modulates β-catenin10. Intriguingly, TMEM9 activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling regardless of APC mutation status (Fig. 2j, Supplementary Figs. 1h, 1i). While β-catenin is degraded by β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination, both MT and WT APC are under lysosomal degradation induced by TMEM9-v-ATPase-activated vesicular acidification (Figs. 4i-4k), proposing the alternative mechanism of Wnt signaling hyperactivation in CRC. It is also noteworthy that TMEM9 is transactivated by β-catenin, suggesting that TMEM9 might function as an amplifier of Wnt signaling in CRC.

TMEM9 KO mice are viable without any discernible phenotype, which might be due to the relatively low expression of TMEM9 in the normal tissues. Given the upregulation of TMEM9 in CRC cells and its pivotal role in CRC cell proliferation, molecular targeting of TMEM9-v-ATPase axis might provide a potential benefit in CRC treatment, with minimal detrimental effects to normal cells. Indeed, v-ATPase inhibitors displayed the strong tumor suppressive effects on CRC suppression in cell lines, organoids, mice, and human PDXs without damage to the normal tissues (Figs. 7, 8).

Together, our results reveal an unexpected positive feedback mechanism of Wnt signaling by TMEM9, a regulator of v-ATPase, and propose that the blockade of TMEM9-v-ATPase might be a viable option for TMEM9-expressing CRC treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xin Wang and Armish Sharma for technical assistance. This work was supported by the University of Texas McGovern Medical School (startup funding to R.K.M.), the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP140563 to J-.I.P.), the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA193297-01 to J-.I.P.; 5R01 GM107079 to P.D.M.; K01DK092320 to R.K.M.; R01 GM126048 to W.W.), the Department of Defense Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program (CA140572 to J-.I.P.), a Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment Grant (IRG-08-061-01 to J-.I.P.), a Center for Stem Cell and Developmental Biology Transformative Grant (MD Anderson Cancer Center to J-.I.P.), an Institutional Research Grant (MD Anderson Cancer Center to J-.I.P.), a New Faculty Award (MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant to J-.I.P.), a Metastasis Research Center Grant (MD Anderson to J-.I.P.), and a Uterine SPORE Career Enhancement Program (MD Anderson to J-.I.P.). The core facility (DNA sequencing and Genetically Engineered Moue Facility) was supported by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clevers H & Nusse R Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149, 1192–1205 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polakis P The many ways of Wnt in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 17, 45–51 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilic J et al. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science 316, 1619–1622 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng X et al. Initiation of Wnt signaling: control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via frizzled, dishevelled and axin functions. Development 135, 367–375 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadigan KM & Waterman ML TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taelman VF et al. Wnt signaling requires sequestration of glycogen synthase kinase 3 inside multivesicular endosomes. Cell 143, 1136–1148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polakis P Wnt signaling in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelps RA et al. A two-step model for colon adenoma initiation and progression caused by APC loss. Cell 137, 623–634 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeulen L et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol 12, 468–476 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voloshanenko O et al. Wnt secretion is required to maintain high levels of Wnt activity in colon cancer cells. Nat Commun 4, 2610 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung YS, Jun S, Lee SH, Sharma A & Park JI Wnt2 complements Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 6, 37257–37268 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niehrs C & Boutros M Trafficking, acidification, and growth factor signaling. Sci Signal 3, pe26 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshansky V & Futai M The V-type H+-ATPase in vesicular trafficking: targeting, regulation and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20, 415–426 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forgac M Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 8, 917–929 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mindell JA Lysosomal acidification mechanisms. Annu Rev Physiol 74, 69–86 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruciat CM et al. Requirement of prorenin receptor and vacuolar H+-ATPase-mediated acidification for Wnt signaling. Science 327, 459–463 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buechling T et al. Wnt/Frizzled signaling requires dPRR, the Drosophila homolog of the prorenin receptor. Current biology : CB 20, 1263–1268 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermle T, Saltukoglu D, Grunewald J, Walz G & Simons M Regulation of Frizzled-dependent planar polarity signaling by a V-ATPase subunit. Current biology : CB 20, 1269–1276 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wielenga VJ et al. Expression of CD44 in Apc and Tcf mutant mice implies regulation by the WNT pathway. Am J Pathol 154, 515–523 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funayama N, Fagotto F, McCrea P & Gumbiner BM Embryonic axis induction by the armadillo repeat domain of beta-catenin: evidence for intracellular signaling. The Journal of cell biology 128, 959–968 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishi T & Forgac M The vacuolar (H+)-ATPases--nature’s most versatile proton pumps. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 3, 94–103 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinouchi K et al. The (pro)renin receptor/ATP6AP2 is essential for vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly in murine cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 107, 30–34 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien CA et al. ID1 and ID3 regulate the self-renewal capacity of human colon cancer-initiating cells through p21. Cancer cell 21, 777–792 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowman EJ, Graham LA, Stevens TH & Bowman BJ The bafilomycin/concanamycin binding site in subunit c of the V-ATPases from Neurospora crassa and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 279, 33131–33138 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K & Boutros M Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat Cell Biol 14, 1036–1045 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urbanelli L et al. Signaling pathways in exosomes biogenesis, secretion and fate. Genes (Basel) 4, 152–170 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) differentially regulates beta-catenin phosphorylation and ubiquitination in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem 281, 17751–17757 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mauvezin C, Nagy P, Juhasz G & Neufeld TP Autophagosome-lysosome fusion is independent of V-ATPase-mediated acidification. Nat Commun 6, 7007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montross WT, Ji H & McCrea PD A beta-catenin/engrailed chimera selectively suppresses Wnt signaling. J Cell Sci 113 ( Pt 10), 1759–1770 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su LK et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science 256, 668–670 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kane PM Disassembly and reassembly of the yeast vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in vivo. J Biol Chem 270, 17025–17032 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graf R, Harvey WR & Wieczorek H Purification and properties of a cytosolic V1-ATPase. The Journal of biological chemistry 271, 20908–20913 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smardon AM, Tarsio M & Kane PM The RAVE complex is essential for stable assembly of the yeast V-ATPase. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 13831–13839 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Najdi R, Holcombe RF & Waterman ML Wnt signaling and colon carcinogenesis: beyond APC. J Carcinog 10, 5 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elias JE & Gygi SP Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods 4, 207–214 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonsalves FC et al. An RNAi-based chemical genetic screen identifies three small-molecule inhibitors of the Wnt/wingless signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 5954–5963 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuhl M & Pandur P Dorsal axis duplication as a functional readout for Wnt activity. Methods Mol Biol 469, 467–476 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park JI et al. Telomerase modulates Wnt signalling by association with target gene chromatin. Nature 460, 66–72 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato T et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262–265 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.