ABSTRACT

Background

As many as 89% of people with Parkinson's disease (PD) develop speech disorders.

Objectives

This randomized controlled trial evaluated two speech treatments for PD matched in intensive dosage and high‐effort mode of delivery, differing in subsystem target: voice (respiratory‐laryngeal) versus articulation (orofacial‐articulatory).

Methods

PD participants were randomized to 1‐month LSVT LOUD (voice), LSVT ARTIC (articulation), or UNTXPD (untreated) groups. Speech clinicians specializing in PD delivered treatment. Primary outcome was sound pressure level (SPL) in reading and spontaneous speech, and secondary outcome was participant‐reported Modified Communication Effectiveness Index (CETI‐M), evaluated at baseline, 1, and 7 months. Healthy controls were matched by age and sex.

Results

At baseline, the combined PD group (n = 64) was significantly worse than healthy controls (n = 20) for SPL (P < 0.05) and CETI‐M (P = 0.0001). At 1 and 7 months, SPL between‐group comparisons showed greater improvements for LSVT LOUD (n = 22) than LSVT ARTIC (n = 20; P < 0.05) and UNTXPD (n = 22; P < 0.05). Sound pressure level differences between LSVT ARTIC and UNTXPD at 1 and 7 months were not significant (P > 0.05). For CETI‐M, between‐group comparisons showed greater improvements for LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC than UNTXPD at 1 month (P = 0.02; P = 0.02). At 7 months, CETI‐M between‐group differences were not significant (P = 0.08). Within‐group CETI‐M improvements for LSVT LOUD were maintained through 7 months (P = 0.0011).

Conclusions

LSVT LOUD showed greater improvements than both LSVT ARTIC and UNTXPD for SPL at 1 and 7 months. For CETI‐M, both LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC improved at 1 month relative to UNTXPD. Only LSVT LOUD maintained CETI‐M improvements at 7 months. © 2018 The Authors. Movement Disorders published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Keywords: speech treatment, RCT, Parkinson's disease, voice, articulation

Research indicates that as many as 89% of patients living with Parkinson's disease (PD) develop speech signs,1, 2, 3, 4, 5 termed hypokinetic dysarthria,6, 7 including disorders of voice (e.g., reduced loudness, monotone, and hoarse, breathy quality),8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 articulation (e.g., imprecise consonants, vowel centralization),15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and rate (increased, decreased, or variable).26, 27, 28 In contrast to previous reports suggesting long latencies from PD diagnosis to onset of identifiable speech signs (median 84 months),29 more recent data from prospective studies using objective, reliable measures sensitive to speech changes suggest that speech signs may appear early22, 30, 31, 32, 33 and progress in severity,25, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 leading to significant declines in functional communication and quality of life.4, 31, 39 Reductions in vocal loudness are among the first and most pervasive changes in speech,1, 6, 7, 14, 40 having negative effects on speech intelligibility when patients are not sufficiently audible to be heard by listeners.8, 41, 42, 43, 44

The neural bases of speech disorders in PD are complex. Reductions in vocal loudness are attributed partly to hypokinesia (reduced amplitude of movement) and rigidity caused by underlying dopaminergic deficiency.42, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 However, abnormalities in central sensory processing (reduced awareness of soft voice), internal cueing (difficulty self‐generating increased loudness), and self‐monitoring of speech output are now reported to contribute.50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 These central sensory and cueing deficits may explain why speech disorders in PD are generally unresponsive to pharmacological or neurosurgical interventions alone40, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65 given that such treatments primarily address motor deficits,12, 61, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 and why traditional speech therapy effects often are not sustained because sensory processing disorders typically are not addressed in these approaches.74, 75, 76, 77, 78

Since the 1990s, development and evaluation of the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD®) has advanced speech treatment efficacy for patients with PD by addressing the complex etiology of the speech disorder.41, 52, 79 LSVT LOUD differs from traditional PD speech treatment in key ways: (1) the singular target of treatment is voice (respiratory‐laryngeal subsystem), specifically increasing amplitude of vocal motor output to override hypokinesia throughout the speech mechanism48, 80; (2) treatment is intensive (16 individual 1‐hour sessions in 1 month, with a high‐effort mode of delivery), consistent with principles promoting activity‐dependent neuroplasticity81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86; and (3) the sensory component of the speech disorder is addressed by retraining sensory perception of normal loudness (self‐monitoring) and internal cueing (self‐generating normal loudness).42, 50, 52 In contrast, traditional speech treatment for PD focused on multiple targets (loudness, respiration, articulation, and rate), was delivered at low dosage (once/twice a week) without high‐effort training, and did not directly address sensory and cueing deficits.75

A previous randomized controlled trial (RCT) in PD compared LSVT LOUD voice treatment (respiratory‐laryngeal target) to an alternative respiratory treatment (respiratory target only), both designed to increase vocal loudness and retrain sensory perception and internal cueing of normal loudness. Outcomes demonstrated that LSVT LOUD produced significant immediate and long‐term improvements (through 24 months) in a key acoustic measure—sound pressure level (SPL), the objective correlate of loudness—supporting treatment efficacy. Furthermore, the magnitude of these changes exceeded those following treatment matched in dosage and mode of delivery, but focusing only on the respiratory system.87, 88, 89 A second RCT90 compared LSVT LOUD to untreated control groups (untreated PD [UNTXPD] and healthy controls [HCs]) and demonstrated that changes in SPL following LSVT LOUD exceeded those for UNTXPD and were maintained for 6 months post‐treatment.90 Effect sizes (ESs) for SPL in these RCTs ranged from 0.65 to 2.03.51, 87, 88, 89, 90 We concluded from the comparison of two treatment targets, both focused on improving vocal loudness, that the target of voice was critical for improvements whereas the respiratory target alone was insufficient.87, 88, 89

Following LSVT LOUD, improvements were also documented in objective measures of articulation,19, 20, 91 rate,87 intonation,89 aerodynamics,92 and perceptual measures of speech intelligibility41, 87 and voice quality,9 as well as measures of swallowing93 and facial expression.94 These findings suggest that driving amplitude through a single treatment target of voice may optimize treatment efficiency through engagement of biomechanical and neurophysiologic linkages between the vocal and articulatory subsystems.95, 96. Given that articulatory movements have been shown to influence a range of laryngeal behaviors, with some correlating strongly with vocal loudness,95, 97, 98, 99, 100 it could be speculated that directly targeting the articulatory subsystem in a similarly intensive manner would have an equal or greater potential for generating speech mechanism‐wide improvements.

To address this, treatment for disordered articulation (orofacial‐articulatory subsystem) was chosen as the treatment target comparator for the current study. Although articulation disorders are commonly observed in PD,20, 21, 25 and have been treated with modest success,101, 102, 103 they have not been treated intensively,104, 105 with the goal to increase amplitude of articulatory motor output to override speech mechanism hypokinesia while retraining sensory perception and internal cueing of articulatory effort.

To dissociate the specific contributions of treatment intensity and target, the current RCT compared a treatment protocol targeting voice (LSVT LOUD), with a treatment protocol targeting articulation (LSVT ARTIC™), equally matched for intensive dosage and mode of delivery and contrasted with no treatment (UNTXPD). We chose not to use a sham treatment to adhere to the ethical principle of equipoise106 and to avoid placing undue time and effort burden on the UNTXPD participants without the potential of therapeutic effect benefit.107 Rather, the UNTXPD group represents natural progression of speech disorders in PD within the framework of scheduled trial visits and medical treatment. This study responds to the need to establish relative efficacy of speech treatments for PD108, 109 and follows CONSORT reporting guidelines for behavioral RCTs.110, 111

Outcomes were measured at 1 and 7 months. The primary outcome reflects amplitude change measured using SPL. The secondary outcome reflects functional change measured by the participant‐reported Modified Communication Effectiveness Index (CETI‐M).

The following are bidirectional hypotheses, a conservative approach which allows for the possibility of differences in either direction:

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant difference at baseline between the combined group of all PD participants and HC participants regarding SPL and CETI‐M.

Hypothesis 2: There are significant differences among LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD regarding changes in SPL over 7 months.

Hypothesis 3: There are significant differences among LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD regarding changes in CETI‐M over 7 months.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design

The design was an unblinded RCT in PD participants using two behavioral speech treatments relative to untreated PD controls. Clinicians administering treatment could not be blinded; participants were aware that they were receiving one of two possible treatments, but specific treatment names (LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC) were never disclosed. UNTXPD were offered complementary treatment poststudy.

Speech data were collected at the National Center for Voice and Speech‐Denver, an affiliate of the University of Colorado‐Boulder (UCB). Additional screening/inclusion and demographic data were collected from neurology and otolaryngology offices in Denver, and the radiology department of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center‐Denver (UCHSC).

Participants

PD patients were recruited from outpatient clinics, support groups, and physicians. HCs were recruited through senior centers and service organizations. All participants (aged 45–85 years) were eligible if they had normal hearing for age and had not smoked within the preceding 4 years.112 PD patients were required to be diagnosed by a neurologist, clinically stable on their antiparkinsonian medication, and within Stages I to IV on the Hoehn and Yahr scale.113 Patients were included if they had no more than mild dementia (Mini‐Mental State Examination [MMSE] ≥25),114 no greater than moderate depression (Beck Depression Inventory‐II [BDI‐II] ≤24),115 and any severity of speech and voice disorder (see Supporting Information). Primary exclusion criteria for patients included diagnosis of atypical PD or other neurological condition at time of screening, speech or voice disorder unrelated to PD, neurosurgical treatment, laryngeal surgery or pathology, intensive speech treatment within 2 years, LSVT LOUD at any time, or swallowing problem requiring immediate attention (see Supporting Information).

The study was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) at UCB and the UCHSC, with written informed consent obtained from all participants; all procedures for de‐identifying shared data were followed. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00123084.

Screening and Randomization

Initial eligibility screening occurred by telephone. Those who satisfied the phone screening (N = 106; 81 PD and 25 HC) participated in face‐to‐face screenings of speech, voice, hearing, depression (BDI‐II), and cognition (MMSE). If this screening was successful, participants underwent videolaryngostroboscopy (Ear Nose Throat [ENT] examination) and modified barium swallow examinations for further screening116, 117, 118 (see Supporting Information).

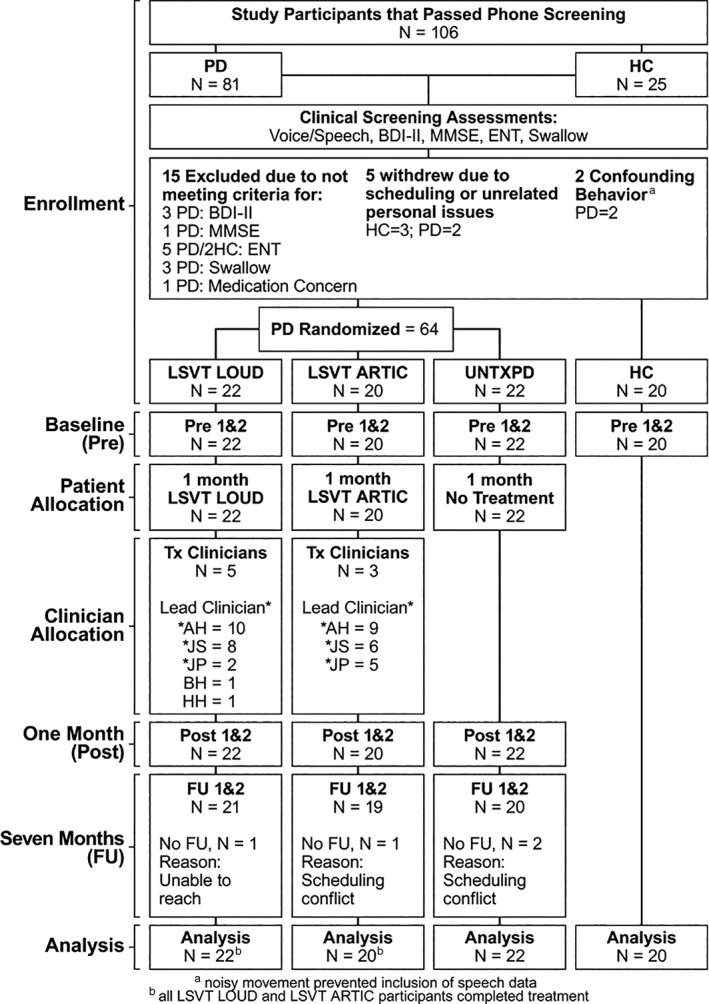

Sixty‐four PD participants met inclusion criteria and were randomized to LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD using a ratio of 1:1:1. Twenty HC participants met inclusion criteria. Randomization used a minimization program that incorporated inclusion/exclusion criteria for each participant. A statistician generated a written allocation from the program, which was forwarded to the treating clinician (assigned according to availability) to enroll the participant (Fig. 1). All participants were compensated for their time.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram outlining the flow of participants through the trial. PD‐Parkinson's disease; HC‐Healthy Control; BDI‐II Beck Depression Inventory‐II; MMSE‐Mini Mental Status Exam; ENT‐Ear Nose Throat examination.

Treating Speech Clinicians

Speech treatments were administered by three speech clinicians specializing in treating PD and certified in LSVT LOUD treatment delivery. The principal investigators and these clinicians developed and extensively piloted LSVT ARTIC.119, 120, 121 Clinicians followed established protocols for both treatments, provided the same encouragement and positive reinforcement during treatment, and conferred frequently to ensure treatment fidelity. All clinicians were compliant with IRB requirements and trained according to the University's required standards of clinical research.122, 123

Treatments

LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC are PD‐specific, neuroplasticity‐principled, standardized protocols, matched on all key variables (intensive dosage, high‐effort exercises, amplitude rescaling, and sensory retraining) and differing only in treatment target (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC speech therapy for PD

| LSVT LOUD | LSVT ARTIC | |

|---|---|---|

| Focus of treatment | Loudness | Enunciation |

| Dosage | Increased movement amplitude directed predominately to respiratory‐laryngeal systems | Increased movement amplitude directed predominately to orofacial‐articulatory system |

| Individual treatment session of 1 hour, 4 consecutive days per week over a 4‐week period | Individual treatment session of 1 hour, 4 consecutive days per week over a 4‐week period | |

| Effort | Push for maximum participant perceived effort | Push for maximum participant perceived effort |

| Daily Exercises, minutes 1 to 30 | ||

| Maximum sustained movements completing multiple repetitions of tasks, minutes 1 to 12 | Sustain the vowel “ah” in a good‐quality, loud voice, for as long as possible | Sustain articulatory placement for “p” (lips closed) and “t” (tongue tip behind upper teeth) with Iowa Oral Pressure Instrument (IOPI); hold for 4 second for each trial |

| Repeat as many as possible in 5‐second trials, each of the following single consonants with precise articulation (voiceless productions): /p/ /t/ /k/ | ||

| Directional movements completing multiple repetitions of tasks, minutes 13 to 23 | Say the vowel “ah” in a good‐quality, loud voice gliding high in pitch; hold for 5 seconds | Repeat as many as possible in 5‐second trials, each of the following minimal pair combinations with precise articulation: /t‐k/, /n‐g/, “oo‐ee,” and “oo‐ah” |

| Say the vowel “ah” in a good‐quality, loud voice gliding low in pitch; hold for 5 seconds | ||

| Functional movements, minutes 24 to 30 | Participant reads 10 self‐generated phrases he/she says daily in functional living (e.g., “Good morning”) using the same effort and loudness as he/she did during the maximum sustained movements exercise | Participant reads 10 self‐generated phrases he/she says daily in functional living (e.g., “Good morning”) using the same effort for enunciation as he/she did during the maximum sustained movements exercise |

| Hierarchy Exercises, minutes 31 to 55 | ||

| Purpose | Train rescaled vocal loudness achieved in the Daily Exercises into context‐specific and variable speaking activities | Train rescaled enunciation achieved in the Daily Exercises into context‐specific and variable speaking activities |

| Method | Incorporate multiple repetitions of reading and conversation tasks with a focus on vocal loudness | Incorporate multiple repetitions of reading and conversation tasks with a focus on enunciate |

| Tasks | Tasks increase in length of utterance and difficulty across weeks, progressing from words to phrases to sentences to reading to conversation, and can be tailored to each participant's goals (e.g., communicate at work or with caregivers) and interests (e.g., speak on topics of golf, cooking) | Tasks increase in length of utterance and difficulty across weeks, progressing from words to phrases to sentences to reading to conversation, and can be tailored to each participant's goals (e.g., communicate at work or with caregivers) and interests (e.g., speak on topics of golf, cooking) |

| Assign Homework Exercises to be completed outside of the therapy room, minutes 56 to 60 | ||

| Duration and repetitions on treatment days (4 days/week) | Subset of the Daily Exercises and Hierarchy Exercises; 10 minutes, performed once per day | Subset of the Daily Exercises and Hierarchy Exercises; 10 minutes, performed once per day |

| Duration and repetitions on nontreatment days (3 days/week) | Subset of the Daily Exercises and Hierarchy Exercises; 15 minutes, performed twice per day | Subset of the Daily Exercises and Hierarchy Exercises; 15 minutes, performed twice per day |

| Conversational Carryover Assignment | Participant is to use the louder voice practiced in exercises in a real‐world communication situation | Participant is to use enunciated speech practiced in exercises in a real‐world communication situation |

| Difficulty level | Matched to the level of the hierarchy where the participant is in treatment | Matched to the level of the hierarchy where the participant is in treatment |

| Shaping techniques | ||

| Purpose and approach | Train vocal loudness that is healthy and within normal limits (i.e., no unwanted vocal strain) through use of modeling (“do what I do”) or tactile/visual cues | Train speech enunciation that is within normal limits (i.e., no excessive movements) through use of modeling (“do what I do”) or tactile/visual cues |

| Sensory calibration | Focus attention on how it feels and sounds to talk with increased vocal loudness (self‐monitoring) and to internally cue (self‐generate) new loudness effort in speech | Focus attention on how it feels and sounds to talk with increased enunciation (self‐monitoring) and to internally cue (self‐generate) new enunciation effort in speech |

| Objective and subjective clinical data collected during each treatment session | Measures of duration, frequency, and sound pressure level | Measures of oral pressure and precise articulatory productions |

| Documentation of percentage of cueing required to implement vocal loudness strategy | Documentation of percentage of cueing required to implement enunciation strategy | |

| Observations of perceptual voice quality | Observations of perceptual speech intelligibility | |

| Participant's self‐reported comments about successful use of the improved loudness in daily communication | Participant's self‐reported comments about successful use of the improved enunciation in daily communication | |

| Participant self‐reported perceived effort | Participant self‐reported perceived effort | |

Both therapies are standardized with respect to intensive dosage. Effort in LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC are based on the participant's self‐perceived effort during treatment tasks, on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being highest perceived effort.87

Control of Bias

Clinicians were made aware that they could impart bias in this unblinded trial and focused their effort to deliver treatments with equipoise124 and reported they were equally invested in both treatments. In post‐treatment interviews, participants were asked their perception of whether their treatment was effective.125

One and 7‐month data collection followed scripted protocols, and interview and experimental data were collected by trained research staff or clinicians. No clinician collected post‐treatment data from a participant he or she treated.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of SPL in reading and spontaneous speech is an objective, acoustic measure with established reliability in studies of PD.8 SPL would be expected to change as a result of driving increased amplitude of motor output across the speech mechanism through vocal or articulatory effort. The secondary outcome was a participant‐reported measure of communicative effectiveness (CETI‐M), which has demonstrated significant correlation with intelligibility126 and voice handicap,127 with established reliability for PD127, 128 (see Supporting Information). For both measures, the unit of analysis was change from baseline.

Data Collection and Analysis

SPL

Data were collected by research staff on 2 separate days (days 1 and 2) within 1 week to allow assessment of test‐retest reliability at baseline, 1, and 7‐month time periods. Collection times were kept consistent for each participant. Participants were not cued to modify their speech (i.e., use loud or enunciate strategies) as per scripted protocol. Participants (1) read two standard passages (Rainbow and Hunter),129, 130 (2) described a picture (Picture),131 (3) spoke about a self‐selected topic for 1 minute (Monologue), (4) described an intensely happy event for 90 seconds (Happy Day),132 and (5) sustained six “ah” phonations for as long as possible (Ah). Data were collected in an IAC sound‐treated booth (IAC Acoustics, North Aurora, IL) using a head‐mounted AKG 420 condenser microphone positioned 8 cm from the lips. The microphone was calibrated to a Type I Sound Level Meter (SLM; Bruel and Kjaer 2238)133 to extract decibels (dB) of SPL.

The cleaned (e.g., edited of coughs), calibrated microphone signals were submitted to SPL analysis using a fully automated, custom‐built software program designed to emulate a Type I SLM resulting in a mean and standard deviation (SD) value for dB SPL at a reference distance of 30 cm.

CETI‐M

CETI‐M was collected at each time period with a minimum of 50% repeated for reliability purposes.134

Participants rated their communicative effectiveness in 10 situations (e.g., “speaking to someone in a noisy environment”) on a 10‐point Likert scale, where 1 = not effective and 10 = extremely effective (see Supporting Information).

Sample Size

Based on previous studies,87, 88, 89, 90 the effect size for SPL was expected to be large (approximately 1). For an overall alpha = 0.05 considering three multiple comparisons (Bonferroni), two‐tailed tests, 20 participants were required per group to yield 80% power.135

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for SPL are presented as means and SDs, for CETI‐M as medians, interquartile ranges, and ranges, and for sex as relative frequencies. Before addressing hypotheses, test‐retest reliability (days 1 and 2) for SPL and CETI‐M was derived using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for baseline, 1‐month, and 7‐month measures.

For Hypothesis 1 (baseline), to compare the combined group of all PD participants to HCs, t‐tests for independent samples were used for SPL and a Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was used for CETI‐M.

For Hypothesis 2 (SPL), one‐way repeated‐measures analyses of variance with Duncan's multiple‐range tests were performed. Multiple imputation was not applied, but mixed‐effects models were used to support bivariate results with the assumption that the very few missing data values were missing completely at random.

For Hypothesis 3 (CETI‐M), if any of the 10 CETI‐M items were missing, nonmissing items were prorated to obtain totals. Kruskal‐Wallis tests incorporated Bonferroni procedures to evaluate differences among PD groups for changes to 1 and 7 months.

Within‐group changes from baseline were tested using mixed‐effects models for SPL and Wilcoxon signed‐rank tests for CETI‐M. ESs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived using Cohen's d for SPL. Analyses adhered to the intention‐to‐treat principle. All tests of hypotheses were two‐tailed, with an overall α‐level of 0.05. No subgroup analyses were conducted, no interim analysis was planned, and there was no data safety monitoring board.

Results

Of 106 individuals screened (81 PD, 25 HC), 64 PD and 20 HCs were enrolled (Fig. 1). Group assignments and descriptive statistics for baseline demographic characteristics and levodopa equivalence136 are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences among the three PD treatment groups for these characteristics (P > 0.05), and between the combined group of all PD participants and HC group for age and sex (P = 0.28; P = 0.75). No participants experienced serious adverse effects.

Table 2.

Demographic, baseline clinical characteristics, baseline SPL across tasks and baseline CETI‐M for participants by group

| Demographics and Other Variables (Weights for Minimization) | PD Treated With LSVT LOUD (N = 22) | PD Treated With LSVT ARTIC (N = 20) | UNTXPD (N = 22) | All PD Combined (N = 64) | HCs (N = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (0.5) | |||||

| N | 15 | 15 | 14 | 44 | 13 |

| % | 68.2 | 75.0 | 63.6 | 68.8 | 65.0 |

| Females (0.5) | |||||

| N | 7 | 5 | 8 | 20 | 7 |

| % | 31.8 | 25.0 | 36.4 | 31.3 | 35.0 |

| Age (0.5) | |||||

| Mean | 68 | 68 | 64 | 67 | 64 |

| SD | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Range | 49,85 | 53,85 | 48,81 | 48,85 | 46,80 |

| Years since diagnosis (0.5) | |||||

| Mean | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | — |

| SD | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | — |

| Range | 0.25,31 | 0,20 | 0.5,14 | 0,31 | — |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage with medication (0.5) | |||||

| Mean | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | — |

| SD | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | — |

| Range | 1,3 | 1,4 | 1,3 | 1,4 | — |

| Swallow (1) | |||||

| Mean | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 |

| SD | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Range | 0,3 | 0,3 | 0,2 | 0,3 | 0,2 |

| Voice (1) | |||||

| Mean | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.7 |

| SD | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Range | 1,3 | 1,3 | 1,3 | 1,3 | 0,2 |

| Articulation (1) | |||||

| Mean | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| SD | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Range | 0,3 | 0,2 | 0,3 | 0,3 | 0,1 |

| BDI‐II (0.25) | |||||

| Mean | 10 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 3 |

| SD | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| Range | 1,20 | 0,20 | 1,21 | 0,21 | 0,13 |

| MMSE (0.25) | |||||

| Mean | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| SD | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Range | 26,30 | 27,30 | 27,30 | 26,30 | 27,30 |

| Levodopa equivalent medication, (mg/d) | |||||

| Mean | 689 | 718 | 726 | 711 | — |

| SD | 486 | 510 | 404 | 460 | — |

| Range | 30,2064 | 0,1773 | 100,1400 | 0,2064 | |

| Baseline SPL Measures by Task, (dB at 30 cm) |

PD Treated With LSVT LOUD (N = 22) |

PD Treated With LSVT ARTIC (N = 20) |

UNTXPD (N = 22) |

All PD Combined (N = 64) |

HCs (N = 20) |

| Rainbow | |||||

| Mean | 70.5 | 71.9 | 70.8 | 71.0 | 72.6 |

| SD | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.1 |

| Range | 64.5,76.6 | 66.8,76.9 | 65.1,77.1 | 64.5,77.1 | 68.6,75.5 |

| Hunter | |||||

| Mean | 70.3 | 71.5 | 70.6 | 70.8 | 72.7 |

| SD | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 |

| Range | 64.4,75.3 | 65.2,79.0 | 65.0,76.1 | 64.4,79.0 | 68.7,76.8 |

| Picture | |||||

| Mean | 69.5 | 70.4 | 69.6 | 69.8 | 71.3 |

| SD | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Range | 62.5,73.8 | 65.2,79.5 | 64.7,75.3 | 62.5,79.5 | 66.5,76.3 |

| Conversation | |||||

| Mean | 69.7 | 70.4 | 69.9 | 70.0 | 71.5 |

| SD | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.2 |

| Range | 64.1,73.8 | 65.0,79.9 | 64.7,75.3 | 64.1,79.9 | 66.9,76.2 |

| Happy | |||||

| Mean | 70.3 | 71.2 | 70.8 | 70.7 | 72.5 |

| SD | 2.9 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Range | 64.9,75.1 | 64.6,81.2 | 65.3,76.7 | 64.6,81.2 | 65.8,77.6 |

| Ah | |||||

| Mean | 75.0 | 73.2 | 76.3 | 74.9 | 76.6 |

| SD | 5.4 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 |

| Range | 62.8,83.9 | 65.5,81.3 | 67.4,87.1 | 62.8,87.1 | 67.6,82.9 |

| Baseline total CETI‐M | |||||

| Median | 64 | 58 | 61 | 62 | 84 |

| Range | 26,100 | 28,86 | 14,98 | 14,100 | 62,100 |

| IQR1 | 57,77 | 48,75 | 54,73 | 53,76 | 76,90 |

Voice and Articulation were measured on a scale from 0 to 5, where 0 = no disorder and 5 = severe disorder (see Supporting Information). Randomization ratio was 1:1:1 performed using a minimization program based on variables and weights chosen a priori.

Rainbow, Hunter, Picture, Conversation, Happy, and Ah refer to speech tasks described in Materials and Methods.

There were significant differences between HCs and combined PD groups for depression, swallowing, voice, and articulation (P < 0.0001), with PD participants exhibiting less optimal characteristics. Significance levels of differences for SPL are presented for Hypothesis 2 in the Results section.

Total CETI‐M score was derived by adding all item scores ranging from 10 (never effective in any situation) to 100 (extremely effective in all situations) and prorated as per Materials and Methods.

IQR is the interquartile range from the 25th to the 75th percentile. Median for changes is the median of within‐subject changes from baseline to subsequent time point.

Reliability

ICCs for test‐retest reliability (days 1 and 2) were >0.80 at baseline, 1 and 7 months for both SPL and CETI‐M. To avoid bias attributed to practice effects, day 1 measures were chosen for statistical analysis.

Hypothesis 1

The combined group of all PD participants had significantly lower (less optimal) SPL values at baseline than the HC group (Table 2) for Rainbow (P = 0.04), Hunter (P = 0.01), Conversation (P = 0.04), and Happy Day (P = 0.03); differences were not significant for Picture (P = 0.06) and Ah (P = 0.18). Median baseline CETI‐M for the PD combined group differed significantly from HCs (P < 0.0001), with PD participants having less optimal scores.

Hypothesis 2

Descriptive statistics for between and within‐group changes in SPL from baseline to 1 and 7 months for each PD group, and corresponding ESs and 95% CIs are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for changes in dB SPL at 30 cm from baseline to 1 and 7 months, ESs, and corresponding 95% CIs for all speech tasks by PD group and pair‐wise group comparisons

| Change From Baseline to 1 month | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSVT LOUD (N = 22) | LSVT ARTIC (N = 20) | UNTXPD (N = 22) | LSVT‐L V. UNTXD |

LSVT‐A V. UNTXD | LSVT‐L V. LSVT‐A |

||||

| Mean [WESa] |

SD [WESCIb] |

Mean [WESa] |

SD [WESCIb] |

Mean [WESa] |

SD [WESCIb] |

BES [BESCI]c |

BES [BESCI]c |

BES [BESCI]c |

|

| Rainbow | 6.3 [2.13] |

3.1 [1.55, 2.59] |

1.3 [0.62] |

2.2 [0.14, 1.10] |

0.5 [0.31] |

1.7 [–0.14, 0.77] |

2.32 [1.52, 3.04] |

0.41 [–0.21, 1.01] |

1.84 [1.09, 2.53] |

| Hunter | 6.4 [2.31] |

2.9 [1.71, 2.81] |

1.4 [0.67] |

2.2 [0.18, 1.15] |

0.4 [0.25] |

1.7 [–0.20, 0.70] |

2.52 [1.69, 3.26] |

0.51 [–0.11, 1.12] |

1.93 [1.16, 2.62] |

| Picture | 5.3 [2.06] |

2.7 [1.47, 2.56] |

1.4 [0.53] |

2.8 [0.05, 0.98] |

0.2 [0.11] |

1.9 [–0.33, 0.55] |

2.18 [1.40, 2.89] |

0.51 [–0.12, 1.11] |

1.42 [0.72, 2.07] |

| Monologue | 5.2 [1.70] |

3.2 [1.17, 2.14] |

1.0 [0.48] |

2.2 [0.00, 0.95] |

0.3 [0.20] |

1.6 [–0.25, 0.65] |

1.94 [1.19, 2.61] |

0.37 [–0.25, 0.97] |

1.52 [0.8, 2.17] |

| Happy | 3.7 [1.49] |

2.6 [0.96, 1.96] |

–0.0 [0.00] |

2.5 [–0.46, 0.46] |

–0.7 [–0.41] |

1.8 [–0.87, 0.04] |

1.97 [1.22, 2.65] |

0.32 [–0.30, 0.92] |

1.45 [0.75, 2.10] |

| Ah | 9.3 [1.88] |

5.2 [1.34, 2.26] |

2.0 [0.50] |

4.2 [0.02, 0.94] |

–0.2 [–0.07] |

3.2 [–0.50, 0.37] |

2.20 [1.42, 2.90] |

0.59 [–0.04, 1.20] |

1.54 [0.82, 2.19] |

| Change From Baseline to 7 Months | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSVT LOUD (N = 21) | LSVT ARTIC (N = 19) | UNTXPD (N = 20) | LSVT‐L V. UNTXD |

LSVT‐A V. UNTXD | LSVT‐L V. LSVT‐A |

||||

| Rainbow | 3.9 [1.78] |

2.3 [1.20, 2.32] |

0.7 [0.34] |

2.2 [–0.15, 0.81] |

0.3 [0.17] |

1.9 [–0.30, 0.64] |

1.70 [0.96, 2.38] |

0.19 [–0.44, 0.82] |

1.42 [0.70, 2.08] |

| Hunter | 3.8 [1.90] |

2.1 [1.29, 2.49] |

0.8 [0.38] |

2.2 [–0.10, 0.86] |

0.3 [0.14] |

2.2 [–0.32, 0.61] |

1.63 [0.89, 2.30] |

0.23 [–0.41, 0.85] |

1.40 [0.68, 2.06] |

| Picture | 3.2 [1.46] |

2.3 [0.92, 1.97] |

0.7 [0.32] |

2.3 [–0.16, 0.80] |

0.4 [0.20] |

2.1 [–0.27, 0.67] |

1.27 [0.58, 1.91] |

0.14 [–0.49, 0.76] |

1.09 [0.40, 1.73] |

| Monologue | 2.9 [1.69] |

1.8 [1.09, 2.33] |

0.6 [0.35] |

1.8 [–0.13, 0.85] |

0.5 [0.29] |

1.8 [–0.27, 0.67] |

1.33 [0.63, 1.98] |

0.06 [–0.57, 0.68] |

1.28 [0.57, 1.93] |

| Happy | 1.9 [1.00] |

2.0 [0.50, 1.50] |

–0.7 [–0.30] |

2.5 [–0.77, 0.19] |

–0.8 [–0.34] |

2.5 [–0.18, 0.77] |

1.20 [0.51, 1.84] |

0.04 [–0.59, 0.67] |

1.16 [0.46, 1.80] |

| Ah | 8.2 [1.96] |

4.4 [1.40, 2.36] |

0.8 [0.25] |

3.4 [–0.23, 0.71] |

–0.4 [–0.09] |

4.7 [–0.80, 0.13] |

1.89 [1.12, 2.59] |

0.29 [–0.35, 0.92] |

1.87 [1.09, 2.57] |

WES is the within group change effect size using Cohen's d.

WESCI is the 95% confidence interval for the within‐group change effect size from Cohen's d.

BES is the between‐group effect size using Cohen's d and corresponding 95% confidence intervals [BESCI] for differences; P values from mixed‐effects model for differences in trends across groups were significant for all tasks at P < 0.0001.

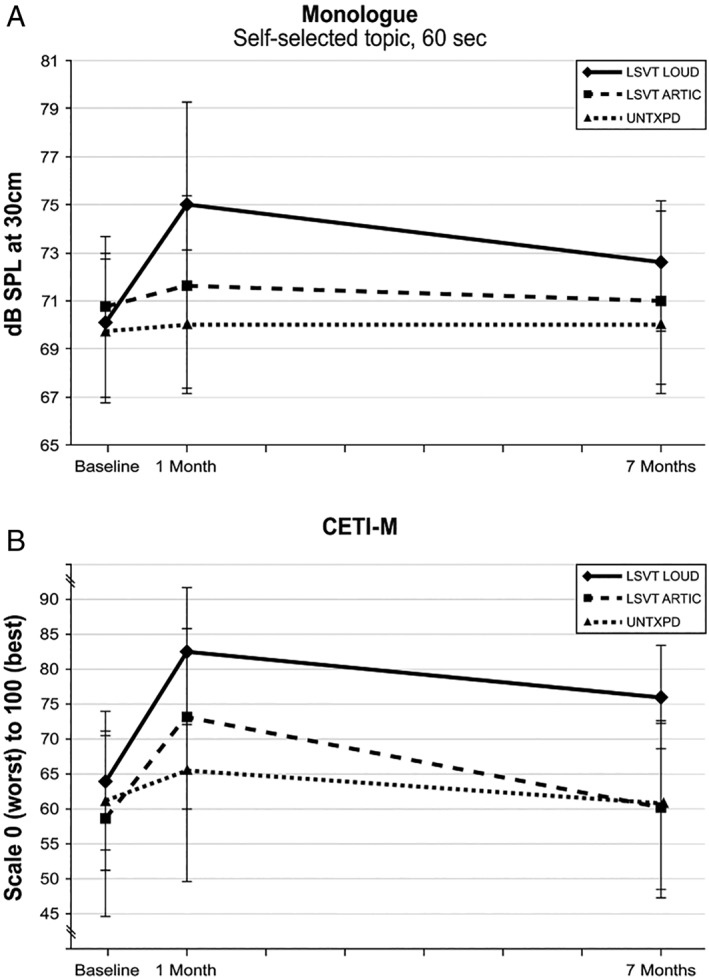

Between‐group increases from baseline to 1 and 7 months in SPL following LSVT LOUD were significantly larger than those for both LSVT ARTIC and UNTXPD for Rainbow, Hunter, Picture, Monologue, Happy Day, and Ah (P < 0.05; P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between LSVT ARTIC and UNTXPD (P > 0.05). Within‐group changes from baseline to 1 and 7 months were significant for all tasks following LSVT LOUD (P < 0.05). Within‐group changes in SPL for LSVT ARTIC were significant at 1 month for all tasks (P < 0.05) except for Happy Day (P = 0.65) and not significant for any task at 7 months (P > 0.09). Within‐group changes in SPL at 1 and 7 months for UNTXPD were not significant for any task (P > 0.15). SPL Monologue data are plotted in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

(A) Means and SDs for dB of SPL at 30 cm for LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD at baseline, 1, and 7 months. The monologue task was plotted as most representative of spontaneous speech. (B) Medians and interquartile ranges from the 25th to the 75th percentile for the CETI‐M scaled 0 to 100 for LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD at baseline, 1, and 7 months.

Hypothesis 3

Descriptive statistics for between and within‐group changes in CETI‐M from baseline to 1 and 7 months for each PD group are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for changes in CETI‐M from baseline to 1 and 7 months

| CETI‐M | PD Treated With LSVT LOUD | PD Treated With LSVT ARTIC | UNTXPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline to 1 month | (n = 22) | (n = 20) | (n = 22) |

| Mediana | 13 | 9 | 1 |

| Range | –12,36 | –4,39 | –16,23 |

| IQRb | 0,21 | 3,23 | –10,9 |

| Change from baseline to 7 months | (n = 21) | (n = 19) | (n = 20) |

| Mediana | 8 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Range | –18,31 | –12,24 | –23,20 |

| IQRa | 2,15 | –3,7 | –10,11 |

Total CETI‐M score was derived by adding all item scores ranging from 10 (never effective in any situation) to 100 (extremely effective in all situations) and prorated as per Materials and Methods.

Median for changes is the median of within‐group subject changes from baseline to subsequent time point.

IQR is the interquartile range from the 25th to the 75th percentile.

There were significant between‐group differences for CETI‐M change from baseline to 1 month indicating greater improvement for LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC relative to UNTXPD (P = 0.02; P = 0.02). Between‐group differences for CETI‐M change from baseline to 7 months for LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC versus UNTXPD groups were not significant (P = 0.08).

Within‐group changes in CETI‐M scores from baseline to 1 month were significant for LSVT LOUD (P = 0.0005) and LSVT ARTIC (P = 0.0001), with no significant changes in the UNTXPD group (P = 0.65). Within‐group CETI‐M changes from baseline to 7 months were significant for LSVT LOUD (P = 0.0011), but not for LSVT ARTIC (P = 0.27) or UNTXPD (P = 0.73). CETI‐M data are plotted in Figure 2B.

At the end of the study, LSVT LOUD and LSVT ARTIC participants were asked, “Out of all the treatment groups you could have been randomized into, do you feel you had the best treatment?”125 Positive responses were comparable between groups (100% vs. 95%, respectively).

Discussion

This RCT evaluated the impact of two speech treatments for PD matched in intensive dosage, differing in speech target: voice (respiratory‐laryngeal/LSVT LOUD) versus articulation (orofacial‐articulatory/LSVT ARTIC), relative to untreated controls.

Regarding Hypothesis 1, significant differences in SPL and CETI‐M were found at baseline between the combined group of all PD participants and the HC group. The finding that SPL was significantly lower in the PD than the HC group is consistent with previous reports of reduced loudness in PD8, 14, 23 and reduced communicative effectiveness and participation.8

Regarding Hypothesis 2, there were significant differences among LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD in SPL over 7 months. Increases in SPL were significantly greater for the voice versus articulation target and were maintained through 7 months only for the target of voice. This magnitude of increase in SPL is both statistically and clinically significant, having an impact on improving audibility8, 137 in a population that struggles with “weak voice.”1, 5, 6, 7, 14, 39 The absence of adverse side effects is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that increased SPL can be accompanied by improved vocal fold closure and voice quality without inducing laryngeal hyperfunction post LSVT LOUD.9, 138

These findings extend our previous research87, 88, 89, 90 by including both an alternative treatment target and untreated control groups. The current findings, that improvements following voice treatment exceeded those following articulation (ES = 1.53) and no treatment (ES = 2.19), together with those of two earlier RCTs89, 90 (ES = 0.65–2.03), build solid evidence for the efficacy of intensive treatment targeting voice for improving speech in PD.

One explanation for these findings comes from our PET imaging studies. In addition to observing treatment‐related modification of neural systems involved in vocalization, a rightward shift of activation in speech motor control and prefrontal and auditory areas139, 140 has been observed post‐LSVT LOUD and not post‐LSVT ARTIC.141, 142

Regarding Hypothesis 3, there were significant differences among LSVT LOUD, LSVT ARTIC, and UNTXPD in CETI‐M immediately post‐treatment with relative improvements for both intensive treatment targets. Improvements in CETI‐M were maintained through 7 months only for LSVT LOUD, suggesting that greater SPL improvement from the voice target may impact self‐rated communication situations such as speaking in noise.128

Limitations and Clinical Implications

Although findings from this third RCT reduce the critical gap in our knowledge of speech treatment in PD, there are limitations.

The RCT was powered based upon previous evidence to detect an effect in the primary outcome SPL. Although the resulting sample size is consistent with behavioral treatment studies,143 it precluded using multivariate statistics. However, we did find significant differences in between‐ and within‐group changes over time. Additionally, although we used multiple comparison procedures for the power analysis and to control for inflation of type 1 errors for three pair‐wise comparisons, we did not adjust for multiple outcomes for SPL.

Whereas PD participants ranged in disease severity and age, generally they had mild‐moderate disease. Nevertheless, it was demonstrated that their speech characteristics and self‐evaluation of communicative effectiveness were significantly worse than those of the HC group at baseline, consistent with reports of speech disorders occurring early and throughout the course of PD.1, 6, 7, 14, 39 Treating speech disorders in mild‐moderate PD may help maintain functional communication and quality of life,4, 5, 31, 39 which is in accord with rehabilitation literature supporting ongoing exercise in mild‐moderate PD.85, 144

The ability to generalize these findings to patients with more advanced disease is supported by our finding of no significant associations between time postdiagnosis (ranging 0–31 years) and within‐group treatment‐related changes in SPL through 7 months (P = 0.30). This suggests that regardless of disease severity, participants showed similar treatment‐related improvements within‐group. This observation is consistent with our previous RCTs87, 88, 89, 90 reporting successful outcomes following LSVT LOUD with more advanced patients including those with atypical PD and post‐DBS‐STN.145, 146, 147, 148

Given that these results emerged from an RCT framework, generalization to “real‐world” situations may be questioned. However, positive outcomes of similar magnitude have been reported following LSVT LOUD by independent researchers globally149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157 and by thousands of clinicians worldwide158 trained in LSVT LOUD for implementation in clinical practice.5, 159

We did not use a sham treatment to control the effect of differential attention.160 However, given the limitations of shams as appropriate comparators in behavioral treatment studies107 and because our RCT was designed to compare two treatments matched in attention, we determined that an untreated control group provided a more useful contrast.

Because this is a behavioral intervention trial, neither clinicians providing treatment nor participants could be blinded. However, great care was taken to evaluate reliability, ensure equipoise, implement standardized training, minimize bias in data collection and analysis, and maintain independence between treating clinicians and those recording data. The finding that participants in both treatment groups perceived they received the most effective treatment supports that treatment delivery was similar across the two approaches and that related attempts to minimize bias were successful.

The choice of the primary outcome of SPL may have been biased inherently towards the voice treatment group. However, previous studies of stimulating articulation 23, 161 (versus treating) have documented an immediate increase in SPL. The current study is the first to intensively treat articulatory effort and measure its impact on SPL and communicative effectiveness. Although there were no between‐group improvements in SPL for LSVT ARTIC at 1 or 7 months, there was a small, but significant, within‐group change at 1 month suggesting an effect on articulatory/vocal linkages,95, 161 supporting the selection of articulation as an appropriate treatment target comparator.

Ongoing analyses of speech intelligibility,162 voice quality,163 swallowing,164 facial expression,165 and imaging (PET)141, 142 in these participants will further clarify mechanisms of response to these speech treatment targets in PD.

Conclusions

This RCT contributes to closing the knowledge gap on effective speech treatments for PD.108, 109 It provides additional support for voice (LSVT LOUD) as an efficacious target when delivered intensively in the treatment of speech in PD with outcomes sustained through 7 months for both objective (SPL) and participant‐reported (CETI‐M) measures. These findings suggest that the treatment target of voice may be uniquely beneficial in improving speech production in PD.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

L.R.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3A, 3B

K.F.: 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B

A.H.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

J.S.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

C.F.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

Data Access and Responsibility

Katherine Freeman takes responsibility for the accuracy of the statistical analyses.

Financial Disclosures

See relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures.

Funding agencies

National Institutes of Health‐National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIH‐NIDCD) R01 DC01150 and LSVT Global, Inc., Tucson, Arizona, USA.

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures

Throughout the active phase of the study, funding was provided by The National Institutes of Health‐National Institute for Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIH‐NIDCD) (R01 DC01150) through the University of Colorado‐Boulder/National Center for Voice and Speech, the primary place of employment for Ramig (Full Professor), Halpern, and Spielman, and where Fox was a consultant. Freeman was a Full Professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA. During poststudy data analysis and manuscript preparation, Ramig, Halpern, and Fox have had employment roles with LSVT Global, and Spielman and Freeman have been paid consultants. Full financial disclosures can be found in the online version of the article.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our patients who continually provide our inspiration. We thank Phillip Gilley, PhD, for his help with randomization and Jill Petska and Ona Reed for their assistance.

Full financial disclosures and author roles may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1. Logemann JA, Fisher HB, Boshes B, Blonsky ER. Frequency and cooccurrence of vocal tract dysfunctions in the speech of a large sample of Parkinson patients. J Speech Hear Disord 1978;43:47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hartelius L, Svensson P. Speech and swallowing symptoms associated with Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis: a survey. Folia Phoniatr Logop 1994;46:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho AK, Iansek R, Marigliani C, Bradshaw JL, Gates S. Speech impairment in a large sample of patients with Parkinson's disease. Behav Neurol 1998;11:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller N, Allcock L, Jones D, Noble E, Hildreth AJ, Burn DJ. Prevalence and pattern of perceived intelligibility changes in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:1188–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schalling E, Johansson K, Hartelius L. Speech and communication changes reported by people with Parkinson's disease. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2017;69:131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darley FL, Aronson AE, Brown JR. Differential diagnostic patterns of dysarthria. J Speech Hear Res 1969;12:246–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darley FL, Aronson AE, Brown JR. Clusters of deviant speech dimensions in the dysarthrias. J Speech Hear Res 1969;12:462–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fox CM, Ramig LO. Vocal sound pressure level and self‐perception of speech and voice in men and women with idiopathic Parkinson disease. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 1997;6:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baumgartner CA, Sapir S, Ramig LO. Voice quality changes following phonatory‐respiratory effort treatment (LSVT®) versus respiratory effort treatment for individuals with Parkinson disease. J Voice 2001;15:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Midi I, Dogan M, Koseoglu M, Can G, Sehitoglu MA, Gunal DI. Voice abnormalities and their relation with motor dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2008;117:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sewall GK, Jiang J, Ford CN. Clinical evaluation of Parkinson's‐related dysphonia. Laryngoscope 2006;116:1740–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plowman‐Prine EK, Okun MS, Sapienza CM, et al. Perceptual characteristics of Parkinsonian speech: a comparison of the pharmacological effects of levodopa across speech and non‐speech motor systems. Neuro Rehabil 2009;24:131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lazarus JP, Vibha D, Handa KK, et al. A study of voice profiles and acoustic signs in patients with Parkinson's disease in North India. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:1125–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ho AK, Bradshaw JL, Iansek R, Alfredson R. Speech volume regulation in Parkinson's disease: effects of implicit cues and explicit instructions. Neuropsychologia 1999;37:1453–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Logemann JA, Fisher HB. Vocal tract control in Parkinson's disease: phonetic feature analysis of misarticulations. J Speech Hear Disord 1981;46:348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weismer G. Acoustic descriptions of dysarthric speech: perceptual correlates and physiological inferences. Semin Speech Lang 1984;5:293–314. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forrest K, Weismer G, Turner GS. Kinematic, acoustic, and perceptual analyses of connected speech produced by Parkinsonian and normal geriatric adults. J Acoust Soc Am 1989;85:2608–2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ackermann H, Ziegler W. Articulatory deficits in Parkinsonian dysarthria: an acoustic analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991;54:1093–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sapir S, Spielman JL, Ramig LO, Story BH, Fox CM. Effects of intensive voice treatment (the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment [LSVT]) on vowel articulation in dysarthric individuals with idiopathic Parkinson disease: acoustic and perceptual findings. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2007;50:899–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sapir S, Ramig LO, Spielman JL, Fox CM. Formant centralization ratio: a proposal for a new acoustic measure of dysarthric speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2010;53:114–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skodda S, Visser W, Schlegel U. Vowel articulation in Parkinson's disease. J Voice 2010;25:467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rusz J, Cmejla R, Tykalova T, et al. Imprecise vowel articulation as a potential early marker of Parkinson's disease: effect of speaking task. J Acoust Soc Am 2013;134:2171–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tjaden K, Lam J, Wilding G. Vowel acoustics in Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis: comparison of clear, loud, and slow speaking conditions. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2013;56:1485–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tjaden K, Wilding GE. Rate and loudness manipulations in dysarthria: acoustic and perceptual findings. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2004;47:766–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Skodda S, Grönheit W, Schlegel U. Impairment of vowel articulation as a possible marker of disease progression in Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 2012;7:e32132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hammen VL, Yorkston KM. Speech and pause characteristics following speech rate reduction in hypokinetic dysarthria. J Commun Disord 1996;29:429–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Skodda S, Schlegel U. Speech rate and rhythm in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:985–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blanchet PG, Snyder GJ. Speech rate deficits in individuals with Parkinson's disease: a review of the literature. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 2009;17:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Müller J, Wenning GK, Verny M, et al. Progression of dysarthria and dysphagia in postmortem‐confirmed Parkinsonian disorders. Arch Neurol 2001;58:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart C, Winfield L, Hunt A, et al. Speech dysfunction in early Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1995;10:562–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller N, Noble E, Jones D, Allcock L, Burn DJ. How do I sound to me? Perceived changes in communication in Parkinson's disease. Clin Rehabil 2008;22:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rusz J, Cmejla R, Ruzickova H, Ruzicka E. Quantitative acoustic measurements for characterization of speech and voice disorders in early untreated Parkinson's disease. J Acoust Soc Am 2011;129:350–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Skodda S, Grönheit W, Mancinelli N, Schlegel U. Progression of voice and speech impairment in the course of Parkinson's disease: a longitudinal study. Parkinsons Dis 2013;2013:389195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. King JB, Ramig LO, Lemke JH, Horii Y. Parkinson's disease: longitudinal changes in acoustic parameters of phonation. NCVS Status Prog Rep 1993;4:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holmes RJ, Oates JM, Phyland DJ, Hughes AJ. Voice characteristics in the progression of Parkinson's disease. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2000;35:407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sapir S, Pawlas A, Ramig LO, et al. Speech and voice abnormalities in Parkinson disease: relation to severity of motor impairment, duration of disease, medication, depression, gender and age. NCVS Status Prog Rep 1999;14:149–161. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Skodda S, Rinsche H, Schlegel U. Progression of dysprosody in Parkinson's disease over time—a longitudinal study. Mov Disord 2009;24:716–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skodda S, Flasskamp A, Schlegel U. Instability of syllable repetition as a marker of disease progression in Parkinson's disease: a longitudinal study. Mov Disord 2011;26:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller N, Noble E, Jones D, Burn D. Life with communication changes in Parkinson's disease. Age Ageing 2006;35:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Theodoros DG. Speech disorder in Parkinson disease In: Theodoros DG, Ramig LO, eds. Communication and Swallowing in Parkinson Disease. San Diego: Plural Publishing, 2011:51–88. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramig LO. The role of phonation in speech intelligibility: a review and preliminary data from patients with Parkinson's disease In: Kent RD, ed. Intelligibility in Speech Disorders: Theory, Measurement, and Management. Amsterdam: John Benjamin, 1992:119–155. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fox CM, Morrison CE, Ramig LO, Sapir S. Current perspectives on the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT) for individuals with idiopathic Parkinson disease. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2002;11:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Adams SG, Haralabous O, Dykstra A, Abrams K, Jog MS. Effects of multi‐talker background noise on the intensity of spoken sentences in Parkinson's disease. Can Acoust 2005;33:94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Neel AT. Effects of loud and amplified speech on sentence and word intelligibility in Parkinson disease. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2009;52:1021–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hallett M, Khoshbin S. A physiological mechanism of bradykinesia. Brain 1980;103:301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pfann KD, Buchman AS, Comella CL, Corcos DM. Control of movement distance in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2001;16:1048–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Berardelli A, Rothwell JC, Thompson PD, Hallett M. Pathophysiology of bradykinesia in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2001;124:2131–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baker KK, Ramig LO, Luschei ES, Smith ME. Thyroarytenoid muscle activity associated with hypophonia in Parkinson disease and aging. Neurology 1998;51:1592–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luschei ES, Ramig LO, Baker KL, Smith ME. Discharge characteristics of laryngeal single motor units during phonation in young and older adults and in persons with Parkinson disease. J Neurophysiol 1999;81:2131–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sapir S. Multiple factors are involved in the dysarthria associated with Parkinson's disease: a review with implications for clinical practice and research. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2014;57:1330–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sapir S, Ramig LO, Fox CM. Intensive voice treatment in Parkinson's disease: Lee Silverman Voice Treatment. Expert Rev Neurother 2011;11:815–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ramig LO, Fox CM, Sapir S. Speech and voice disorders in Parkinson's disease In: Olanow CW, Stocchi F, Lang AE, eds. Parkinson's Disease: Non‐Motor and Non‐Dopaminergic Features. Oxford: Wiley–Blackwell, 2011:348–362. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ho AK, Bradshaw JL, Iansek R. Volume perception in Parkinsonian speech. Mov Disord 2000;15:1125–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kwan LC, Whitehill TL. Perception of speech by individuals with Parkinson's disease: a review. Parkinsons Dis 2011;2011:389767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mollaei F, Shiller DM, Gracco VL. Sensorimotor adaptation of speech in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2013;28:1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Arnold C, Gehrig J, Gispert S, Seifried C, Kell CA. Pathomechanisms and compensatory efforts related to Parkinsonian speech. Neuroimage Clin 2014;4:82–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu H, Wang EQ, Metman LV, Larson CR. Vocal responses to perturbations in voice auditory feedback in individuals with Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 2012;7:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Houde JF, Nagarajan S, Heinks T, Fox CM, Ramig LO, Marks WJ. The effect of voice therapy on feedback control in Parkinsonian speech. Mov Disord 2004;19:S403. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Guehl D, Burbaud P, Lorenzi C, et al. Auditory temporal processing in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia 2008;46:2326–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Clark JP, Adams SG, Dykstra AD, Moodie S, Jog M. Loudness perception and speech intensity control in Parkinson's disease. J Commun Disord 2014;51:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schulz GM, Grant MK. Effects of speech therapy and pharmacologic and surgical treatments on voice and speech in Parkinson's disease: a review of the literature. J Commun Disord 2000;33:59–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ramig LO, Fox C, Sapir S. Speech disorders in Parkinson's disease and the effects of pharmacological, surgical and speech treatment with emphasis on Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT®) In: Koller WC, Melamed E, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology Volume 83 (3rd series) Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders, Part 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V., 2007:385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pinto S, Gentil M, Krack P, Sauleau P, Fraix V, Benabid AL, Pollak P. Changes induced by levodopa and subthalamic nucleus stimulation on Parkinsonian speech. Mov Disord 2005;20:1507–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pinto S, Ozsancak C, Tripoliti E, Thobois S, Limousin‐Dowsey P, Auzou P. Treatments for dysarthria in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Trail M, Fox C, Ramig LO, Sapir S, Howard J, Lai EC. Speech treatment for Parkinson's disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2005;20:205–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Larson K, Ramig LO, Scherer RC. Acoustic and glottographic voice analysis during drug‐related fluctuation in Parkinson's disease. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 1994;2:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- 67. D'Alatri L, Paludetti G, Contarino MF, Galla S, Marchese MR, Bentivoglio AR. Effects of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation and medication on Parkinsonian speech impairment. J Voice 2008;22:365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ho AK, Bradshaw JL, Iansek R. For better or worse: the effect of Levodopa on speech in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Skodda S, Visser W, Schlegel U. Short‐ and long‐term dopaminergic effects on dysarthria in early Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm 2010;117:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Skodda S. Effect of deep brain stimulation on speech performance in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis 2012;2012:850596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Deuschl G, Paschen S, Witt K. Clinical outcome of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease In: Lozano AM, Hallett M, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology (volume 116, 3rd series) Brain Stimulation. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V., 2013:107–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tripoliti E, Zrinzo L, Martinez‐Torres I, et al. Effects of contact location and voltage amplitude on speech and movement in bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord 2008;23:2377–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Goberman AM, Coelho C. Acoustic analysis of Parkinsonian speech I: speech characteristics and L‐Dopa therapy. NeuroRehabilitation 2002;17:237–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Allan CM. Treatment of non‐fluent speech resulting from neurological disease—treatment of dysarthria. Br J Disord Commun 1970;5: 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Aronson AE. Organic voice disorders: neurologic disease. Clin Voice Disord 1985;2:76–125. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Greene HCL. The Voice and Its Disorders. London: Pitman Medical; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sarno MT. Speech impairment in Parkinson's disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1968;49:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Weiner WJ, Singer C. Parkinson's disease and nonpharmacologic treatment programs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989;37:359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ramig LO, Bonitati CM, Lemke JH, Horii Y. Voice treatment for patients with Parkinson disease: development of an approach and preliminary efficacy data. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 1994;2:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sapir S, Ramig LO, Fox CM. Assessment and treatment of the speech disorder in Parkinson disease In: Theodoros DG, Ramig LO, eds. Communication and Swallowing in Parkinson Disease. San Diego: Plural Publishing, 2011:89–122. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kleim JA, Jones TA, Schallert T. Motor enrichment and the induction of plasticity before or after brain injury. Neurochem Res 2003;28:1757–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience‐dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2008;51:S225–S239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Baker E. Optimal intervention intensity in speech‐language pathology: discoveries, challenges, and unchartered territories. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2012;14:478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ahlskog JE. Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology 2011;77:288–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Frazzitta G, Maestri R, Bertotti G, et al. Intensive rehabilitation treatment in early Parkinson's disease: a randomized pilot study with a 2‐year follow‐up. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015;29:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Fox CM, Ramig LO, Ciucci MR, Sapir S, McFarland DH, Farley BG. The science and practice of LSVT/LOUD: neural plasticity‐principled approach to treating individuals with Parkinson disease and other neurological disorders. Semin Speech Lang 2006;27:283–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ramig LO, Countryman S, Thompson LL, Horii Y. Comparison of two forms of intensive speech treatment for Parkinson disease. J Speech Hear Res 1995;38:1232–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ramig LO, Countryman S, O'Brien C, Hoehn M, Thompson LL. Intensive speech treatment for patients with Parkinson's disease: short‐ and long‐term comparison of two techniques. Neurology 1996;47:1496–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ramig LO, Sapir S, Countryman S, et al. Intensive voice treatment (LSVT®) for individuals with Parkinson's disease: a two‐year follow‐up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ramig LO, Sapir S, Fox CM, Countryman S. Changes in vocal loudness following intensive voice treatment (LSVT®) in individuals with Parkinson's disease: a comparison with untreated patients and normal age‐matched controls. Mov Disord 2001;16:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dromey C, Ramig LO, Johnson AB. Phonatory and articulatory changes associated with increased vocal intensity in Parkinson disease: a case study. J Speech Hear Res 1995;38:751–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ramig LO, Dromey C. Aerodynamic mechanisms underlying treatment‐related changes in vocal intensity in patients with Parkinson disease. J Speech Hear Res 1996;39:798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. El Sharkawi A, Ramig LO, Logemann JA, et al. Swallowing and voice effects of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT®): a pilot study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Spielman JL, Borod JC, Ramig LO. The effects of intensive voice treatment on facial expressiveness in Parkinson disease: preliminary data. Cogn Behav Neurol 2003;16:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. McClean MD, Tasko SM. Association of orofacial with laryngeal and respiratory motor output during speech. Exp Brain Res 2002;146:481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. McFarland DH, Tremblay P. Clinical implications of cross‐system interactions. Semin Speech Lang 2006;27:300–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cookman S, Verdolini K. Interrelation of mandibular laryngeal functions. J Voice 1999;13:11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Higgins MB, Netsell R, Schulte L. Vowel‐related differences in laryngeal articulatory and phonatory function. J Speech Lang Hear Res 1998;41:712–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Larson KK, Sapir S. Orolaryngeal reflex responses to changes in affective state. J Speech Lang Hear Res 1995;38:990–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sapir S. The intrinsic path of vowels: theoretical, physiological, and clinical considerations. J Voice 1989;3:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Duffy JF. Hypokinetic dysarthria In: Duffy JR, ed. Motor Speech Disorders: Substrates, Differential Diagnosis, and Management. St. Louis: Mosby, 2005:187–215. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Rosenbek JC, LaPointe LL. The dysarthrias: description, diagnosis, and treatment In: Johns D, ed. Clinical Management of Neurogenic Communicative Disorders. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1985:97–152. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yorkston KM, Beukelman DR, Bell KR. Clinical Management of Dysarthric Speakers. Boston, MA: College Hill Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Dromey C. Articulatory kinematics in patients with Parkinson disease using different speech treatment approaches. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 2000;8:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Goberman AM, Elmer LW. Acoustic analysis of clear versus conversational speech in individuals with Parkinson disease. J Commun Disord 2005;38:215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Schwartz CE, Chesney MA, Irvine MJ, Keefe FJ. The control group dilemma in clinical research: applications for psychosocial and behavioral medicine trials. Psychosom Med 1997;59:362–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Rains JC, Penzien DB. Behavioral research and the double‐blind placebo‐controlled methodology: challenges in applying biomedical standard to behavioral headache research. Headache 2005;45:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Atkinson‐Clement C, Sadat J, Pinto S. Behavioral treatments for speech in Parkinson's disease: meta‐analyses and review of the literature. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2015;5:233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Herd CP, Tomlinson CL, Deane KH, et al. Speech and language therapy versus placebo or no intervention for speech problems in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(8):CD002812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trials abstracts. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Waller LA, et al. Smoking cessation and lung function in mild‐to‐moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression, and mortality. Neurology 1967;17:427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini‐mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory‐II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 1996:38. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Blitzer A, Brin MF, Ramig LO. Neurologic Disorders of the Larynx. New York, NY: Thieme; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Logemann JA. The Evaluation and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders, 2nd ed. Austin, TX: Pro‐Ed; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Whelan BM. Assessment and treatment of cognitive‐linguistic disorder in Parkinson disease In: Theodoros DG, Ramig LO, eds. Communication and Swallowing in Parkinson Disease. San Diego: Plural Publishing; 2011:179–198. [Google Scholar]

- 119. Spielman J, Halpern A, Ramig L. Changes in speech production following intensive voice vs. intensive articulation therapy in Parkinson disease: a preliminary study. Poster session presented at: The 14th Biennial Conference on Motor Speech; 2008. March 6–9; Monterey, CA.

- 120. Halpern A, Spielman J, Ramig L, Cable J, Panzer I, Sharpley A. The effects of loudness and noise on speech intelligibility in Parkinson disease. Poster session presented at: The 11th International Congress of Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders; 2007. June 3–7; Istanbul, Turkey.

- 121. Halpern A, Spielman J, Ramig L, Panzer I, Sharpley A, Gustafson H. Speech intelligibility measured in noise: the effects of loudness vs. articulation treatment in Parkinson disease. Poster session presented at: The Annual Conference of the American Speech‐Language Hearing Association; 2008. November 20–22; Chicago, IL.

- 122. Robey RR, Schultz MC. A model for conducting clinical‐outcome research: an adaptation of the standard protocol for use in aphasiology. Aphasiology 1998;12:787–810. [Google Scholar]

- 123. Robey RR. A five‐phase model for clinical‐outcome research. J Commun Disord 2004;37:401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Djulbegovic B, Cantor A, Clarke M. The importance of the preservation of the ethical principle of equipoise in the design of clinical trials: relative impact of the methodological quality domains on the treatment effect in randomized controlled trials. Account Res 2003;10:301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Goetz CG, Janko K, Blasucci L, Jaglin JA. Impact of placebo assignment in clinical trials of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2003;18:1146–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Ball LJ, Beukelman DR, Pattee GL. Communication effectiveness of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Commun Disord 2004;37:197–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Spielman J, Gilley P, Halpern A, Ramig LO. Relationship of Communicative Effectiveness to Voice Handicap, Acoustics, and Behavioral Characteristics in People with Parkinson Disease. Poster session presented at: The 15th Biennial Conference on Motor Speech; 2010. March 7–10; Savannah, GA.

- 128. Dykstra A, Adams S, Jog M. The effect of hypophonia on communication effectiveness in Parkinson's disease. Poster session presented at: The 14th Biennial Conference on Motor Speech; 2008. March 6–9; Monterey, CA.

- 129. Fairbanks G. Voice and Articulation Drillbook. New York, NY: Harder and Brothers; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 130. Crystal TH, House AS. Segmental durations in connected speech signals: preliminary results. J Acoust Soc Am 1982;72:705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The Assessment of Aphasia and Related Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Borod JC, Welkowitz J, Obler LK. The New York Emotion Battery. Unpublished materials, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Department of Neurology, New York, NY, 1992.

- 133. Švec JG, Popolo PS, Titze IR. Measurement of vocal doses in speech: experimental procedure and signal processing. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 2003;28:181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. de Riesthal M, Ross KB. Patient reported outcome measures in neurologic communication disorders: an update. Perspect Neurophysiol Neurogen Speech Lang Disord 2015;25:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 135. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 1992;1:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 136. Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:2649–2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Moore BCJ, ed. An Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing. San Diego, CA: Academic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 138. Smith ME, Ramig LO, Dromey C, Perez KS, Samandari R. Intensive voice treatment in Parkinson disease: laryngostroboscopic findings. J Voice 1995;9:453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Liotti M, Ramig LO, Vogel D, et al. Hypophonia in Parkinson's disease: neural correlates of voice treatment revealed by PET. Neurology 2003;60:432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Narayana S, Fox PT, Zhang W, et al. Neural correlates of efficacy of voice therapy in Parkinson's disease identified by performance—correlation analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 2010;31:222–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Narayana S, Franklin C, Peterson E, Robin D, Fox PT, Ramig LO. Voice therapy normalizes feedforward and feedback networks of the speech motor system. Mov Disord 2017;32(Suppl 2):A1365. [Google Scholar]

- 142. Narayana S, Franklin C, Peterson E, Robin D, Fox PT, Ramig LO. Voice therapy normalizes feedforward and feedback networks of the speech motor system. Poster presented at: The International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain; 2017b. June 25–29; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

- 143. Huang JH, Su QM, Yang J, et al. Sample sizes in dosage investigational clinical trials: a systematic evaluation. Drug Des Dev Ther 2015;9:305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Schenkman M, Hall DA, Barón AE, Schwartz RS, Mettler P, Kohrt WM. Exercise for people in early‐ or mid‐stage Parkinson disease: a 16‐month randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2012;92:1395–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Countryman S, Ramig LO, Pawlas A. Speech and voice deficits in Parkinsonian plus syndromes: can they be treated? J Med Speech Lang Pathol 1994;2:211–225. [Google Scholar]

- 146. Spielman JL, Mahler L, Halpern A, Gilley P, Klepitskaya O, Ramig LO. Intensive voice treatment (LSVT®LOUD) for Parkinson's disease following deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. J Commun Disord 2011;44:688–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Sale P, Castiglioni D, De Pandis MF, et al. The Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT®) speech therapy in progressive supranuclear palsy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2015;51:569–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Countryman S, Hicks J, Ramig LO, Smith ME. Supraglottal hyperadduction in an individual with Parkinson disease: a clinical treatment note. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 1997;6:74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 149. Theodoros DG, Thompson‐Ward EC, Murdoch BE, Lethlean J, Silburn P. The effects of the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment program on motor speech function in Parkinson disease following thalamotomy and pallidotomy surgery: a case study. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 1999;7:157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 150. Constantinescu G, Theodoros D, Russell T, Ward E, Wilson S, Wootton R. Treating disordered speech and voice in Parkinson's disease online: a randomized controlled non‐inferiority trial. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2011;46:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Howell S, Tripoliti E, Pring T. Delivering the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT) by web camera: a feasibility study. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2009;44:287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Theodoros DG, Constantinescu G, Russell TG, Ward EC, Wilson SJ, Wootton R. Treating the speech disorder in Parkinson's disease online. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Theodoros DG, Hill AJ, Russell TG. Clinical and quality of life outcomes of speech treatment for Parkinson's disease delivered to the home via telerehabilitation: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2016;25:214–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]