Abstract

Purpose

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective in preventing HIV transmission. Finding a PrEP provider, however, can be a barrier to accessing care. This study explores the distribution of publicly listed PrEP-providing clinics in the United States.

Methods

Data regarding 2,094 PrEP-providing clinics come from PrEP Locator, a national database of PrEP-providing clinics. We compared the distribution of these PrEP clinics to the distribution of new HIV diagnoses within various geographical areas and by key populations.

Results

Most (43/50) states had <1 PrEP-providing clinic per 100,000 population. Among states, the median was two clinics per 1,000 PrEP-eligible MSM. Differences between disease burden and service provision were seen for counties with higher proportions of their residents living in poverty, lacking health insurance, identifying as African American, or identifying as Hispanic/Latino. The Southern region accounted for over half of all new HIV diagnoses, but only one-quarter of PrEP-providing clinics.

Conclusions

The current number of PrEP-providing clinics is not sufficient to meet needs. Additionally, PrEP-providing clinics are unevenly distributed compared to disease burden, with poor coverage in the Southern divisions and areas with higher poverty, uninsured, and larger minority populations. PrEP services should be expanded and targeted to address disparities.

Keywords: Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, HIV, Primary Prevention

Introduction

PrEP is highly effective in preventing HIV transmission.(1) PrEP is indicated by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexual men and women, and people who inject drugs.(2) PrEP is effective in preventing HIV across different populations, with a meta-analysis finding a 70% reduction in HIV infection risk among groups with high (>70%) PrEP adherence.(3) Individuals in an integrated healthcare system who had initiated and remained on PrEP had no HIV seroconversions in 850 person-years of accumulated follow-up time, however, two seroconversions occurred among individuals who had discontinued PrEP.(4)

PrEP initiations have grown rapidly in the United States. From 2012 to 2015, there was a 6.9 fold increase in individuals initiating PrEP regimens.(5) In the 2015 National HIV/AIDS Strategy, the states of New York and Washington were highlighted for their “End AIDS” programs, both of which facilitate access to PrEP.(6) Currently, dozens of other states and cities have projects, specified clinics, and programs that are dedicated to providing PrEP.(7) Despite these efforts, PrEP uptake remains low compared to estimated need. CDC estimates that one-quarter of all MSM are eligible for PrEP,(2) yet survey data indicate that uptake is around 4%.(8)

One barrier to PrEP uptake is the need to find an appropriate provider. All providers who meet standard prescriptive authority rules can prescribe PrEP, but not all providers are willing. A qualitative exploration found rationales of providers for not prescribing PrEP to include concerns regarding poor adherence, toxicity, and the potential for generation of drug-resistance.(9) Other providers may be unaware of PrEP (10, 11) or have concerns regarding cost.(12) Providers who have experience treating patients living with HIV, have previously prescribed post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), or are part of a larger practice group were more willing to prescribe PrEP.(10, 13) These attributes may increase the likelihood of a physician prescribing PrEP due to increased familiarity with prescribing antiretroviral medication. Similarly, the PrEP ‘purview paradox’ notes that primary care physicians view PrEP antiretroviral regimens and adherence issues as the domain of HIV care specialists, and HIV care specialists are less likely to see the HIV-negative patients who would be eligible for PrEP.(14)

In the short time that tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF/FTC) has been indicated for PrEP by the US Food and Drug Administration, racial disparities in PrEP uptake have developed. For instance, 44% of new HIV diagnoses in 2014 were among African Americans, yet only 10% of individuals initiating PrEP that year were African American.(15) Twenty-three percent of new HIV diagnoses in 2014 were among Hispanic Americans, yet only 12% of individuals initiating PrEP were Hispanic. Reasons for disparities are likely multifactoral, with diverse contributors such as social stigma, medical mistrust, financial barriers, and awareness. (16, 17) Medical students in one study were more likely to expect sexual risk compensation in African American patients than white patients; these beliefs indirectly reduced willingness to prescribe PrEP to African American patients.(18)

Given hesitancy or unwillingness to prescribe PrEP by some clinicians, and in light of racial disparities in PrEP use, it is critical to minimize known barriers to accessing PrEP. Minorities and individuals with lower incomes are more likely to face geographic barriers to accessing healthcare.(19) Geographic availability has been shown to impact access to HIV care and may also be critical to PrEP access.(20) Proximity of providers may be particularly important because individuals on PrEP are recommended by CDC to have four clinician visits each year.(21) Using data from PrEP Locator, a national database of publicly-listed clinics that prescribe PrEP, we describe the geographic distribution of PrEP clinics in the United States. This county-level analysis explores how the density of PrEP-providing clinics aligns with race, income, insurance status, and urbanicity in comparison to the overall population, to estimated numbers of MSM eligible for PrEP, and to new HIV diagnoses.

Methods

Data regarding PrEP-providing clinics come from PrEP Locator, a national and publicly-available database of clinics developed by the authors.(22, 23) The PrEP Locator database was developed from over 50 different data sources, including all available state health department directories, local health department directories, non-governmental organization directories, and HIV-related medical organization member surveys. To be eligible for inclusion, all clinics in the database were determined to have a working phone number, have personnel at that phone number confirm that the clinic prescribes PrEP, and have a clinician with appropriate licensure to prescribe PrEP determined by state licensure databases. Clinic eligibility was assessed through phone calls by Emory staff. Nonresponsive clinics, having not responded to a minimum of three calls, were excluded from the database. Updates to the database occurred through opt-in suggestions to add or update provider information through a public webform, or through collaborations with state and local directories to update database information on a regular basis. Proposed updates to the database are placed in a holding pen, which is then vetted by Emory staff prior to release. Further documentation regarding the development and procedures of PrEP Locator are available.(22) Data for the present analysis were extracted from the Locator database in February 2018.

County- and state-level data for age, gender, the proportion of residents living in poverty, and the proportion of residents uninsured were obtained from the US Census Bureau. Poverty is defined as three times the cost of a minimum food diet(24) and uninsured is defined as individuals not covered by any type of private or government insurance for any part of the previous year.(25) Geographic regions were categorized into nine divisions according to standard US Census Bureau divisions. To explore possible racial disparities in the distribution of PrEP clinics, we used race/ethnicity estimates: for state-level data we used the year 2016 American Community Survey of the US Census Bureau (ACS), and for county-specific data we used the four year 2012–2016 ACS. We ranked counties by the proportion within each county that identified as African American race or Hispanic ethnicity (inclusive of all races), and categorized the data as <5%, 5 – <10%, 10 – <20%, and ≥ 20% of each race/ethnicity. Counties were also ranked based on the proportion of residents living in poverty and the proportion of residents uninsured into categories of <10%, 10 – <15%, 15 – <20%, and ≥ 20%. These cut points were chosen to provide meaningful intervals, guided by histograms of each variable’s distribution. Urbanicity classification was based on the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Urban-Rural Classification Scheme.

New HIV diagnoses and prevalent HIV cases from 2016 are from the AIDSVu database,(26) which uses data from the CDC National HIV Surveillance System (NHSS) for county-level data. The NHSS is a database of HIV/AIDS diagnosis surveillance conducted by state or territory health departments according to uniform surveillance case definitions and case report forms, with data then provided to CDC. In the AIDSVu dataset, geographic areas with either small numerator (HIV diagnosis or prevalent case numbers < 5) or small denominator (number of people in a particular population < 100) data are suppressed to protect identity. We estimated values for counties with suppressed data by subtracting, for each state, all known county-level values of HIV diagnoses from the state total. The remainder (the total from unknown counties) was distributed evenly to counties with missing data. To assess HIV diagnoses in urban areas, we included county-level diagnosis data for 33 cities in the AIDSVu database. AIDSVu obtains these data directly from state and local health departments. City limits for this analysis were defined by core-based statistical areas (CBSAs). We estimated the number of PrEP-eligible MSM in each state and city using small-area population estimates for MSM multiplied by the CDC-estimated proportion of MSM indicated for PrEP (24.7%). (27) MSM population estimates were calculated based on previously published methods, here replicated based on current 2016 US Census data. (28, 29) In brief, this estimation method uses the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and urbanicity-stratified weights derived from ACS to estimate population counts for the number of MSM in each county in the United States.

We calculated the number, and percent of national total, of PrEP-providing clinics in US Census Divisions (excluding Puerto Rico). The numbers of PrEP clinics are also displayed for groups of counties ranked by urbanicity, proportion of residents living in poverty or uninsured, and concentration of the population African American or Hispanic (Table 1). Ratios of PrEP clinics divided by new HIV diagnoses were calculated at the county level, and are shown in Table 1 to explore the distribution of PrEP clinics relative to epidemic need. Tables 2 and 3 provide state- and city-level data on the number of PrEP clinics in geographic areas. We calculated clinic prevalence (clinics per 100,000 population over 13 years of age), ratios of clinics per 1,000 PrEP-eligible MSM, and ratios of clinics per 1,000 new HIV diagnoses for each area. Clinic prevalence is calculated to allow for assessment of the number of clinics relative to the population size for each geographic area. Ratios of clinics per PrEP-eligible MSM are used to compare the number of clinics relative to the number of individuals indicated for the service. Ratios of clinics to new HIV diagnoses are used to compare the number of clinics to epidemic need. The dataset may not contain all publicly-listed PrEP clinics. It is, however, the only nationally available method to find PrEP-providing clinics and it includes data from all other major listings of PrEP clinics such as health departments and medical organizations. Therefore, we believe the data approximate a census of clinics that an individual seeking PrEP would be able to easily access, so we do not use inferential statistics to generalize to a broader population of clinics, such as statistical significance testing.

Table 1.

Distribution of 2,094 PrEP-Providing Clinics and New HIV Diagnoses in the United States

| PrEP-Providing Clinics, 2018 |

PrEP Eligible MSM, 2016 | PrEP Need1 New Diagnoses, 2016 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of national total |

N | % of national total |

Clinics per 1,000 |

N | % of national total |

Clinics per 1,000 |

||

| Census Division | |||||||||

| East North Central | 260 | 12 | 115,444 | 14 | 2.3 | 3,807 | 10 | 68.3 | |

| East South Central | 67 | 3 | 37,396 | 4 | 1.8 | 1,991 | 5 | 33.7 | |

| Middle Atlantic | 365 | 17 | 87,396 | 10 | 4.2 | 5,168 | 13 | 70.6 | |

| Mountain | 197 | 9 | 66,586 | 8 | 3.0 | 2,067 | 5 | 95.3 | |

| New England | 148 | 7 | 27,824 | 3 | 5.3 | 1,131 | 3 | 130.9 | |

| Pacific | 485 | 23 | 179,799 | 21 | 2.7 | 5,733 | 14 | 84.6 | |

| South Atlantic | 333 | 16 | 186,289 | 22 | 1.8 | 12,303 | 31 | 27.1 | |

| West North Central | 100 | 5 | 38,928 | 5 | 2.6 | 1,232 | 3 | 81.2 | |

| West South Central | 139 | 7 | 110,508 | 13 | 1.3 | 6,222 | 16 | 22.3 | |

| Urbanicitya (by county) | |||||||||

| Large central metro | 1,062 | 51 | 447,717 | 53 | 2.4 | 20,344 | 51 | 52.2 | |

| Large fringe metro | 381 | 18 | 205,695 | 24 | 1.9 | 7,832 | 20 | 48.6 | |

| Medium metro | 370 | 18 | 101,172 | 12 | 3.7 | 6,544 | 17 | 56.5 | |

| Small metro | 143 | 7 | 39,911 | 5 | 3.6 | 2,072 | 5 | 69.0 | |

| Micropolitan | 88 | 4 | 35,431 | 4 | 2.5 | 1,354 | 3 | 65.0 | |

| Noncore | 50 | 2 | 20,232 | 2 | 2.5 | 1,506 | 4 | 33.2 | |

| Poverty (by county) | |||||||||

| Less than 10% poverty | 273 | 13 | 126,253 | 15 | 2.2 | 3,878 | 10 | 70.4 | |

| 10% – <15% poverty | 677 | 32 | 249,405 | 29 | 2.7 | 9,698 | 24 | 69.8 | |

| 15% – <20%poverty | 855 | 41 | 379,932 | 45 | 2.3 | 18,864 | 48 | 45.3 | |

| 20% or more poverty | 289 | 14 | 94,580 | 11 | 3.1 | 7,215 | 18 | 40.1 | |

| Percent Uninsured (by county) | |||||||||

| Less than 10% uninsured | 922 | 44 | 297,035 | 35 | 3.1 | 9,484 | 24 | 97.2 | |

| 10% – <15% uninsured | 793 | 38 | 332,874 | 39 | 2.4 | 16,644 | 42 | 47.6 | |

| 15% – <20% uninsured | 299 | 14 | 157,017 | 18 | 1.9 | 9,232 | 23 | 32.4 | |

| 20% or more uninsured | 80 | 4 | 63,244 | 7 | 1.3 | 4,294 | 11 | 18.6 | |

| African American Concentration (by county) | |||||||||

| Less than 5% African American | 555 | 27 | 207,048 | 24 | 2.7 | 5,906 | 15 | 94.0 | |

| 5% – <10% African American | 496 | 24 | 209,107 | 25 | 2.4 | 7,909 | 20 | 62.7 | |

| 10% – <20% African American | 474 | 23 | 198,946 | 23 | 2.4 | 10,260 | 26 | 46.2 | |

| 20% or more African American | 569 | 27 | 235,068 | 28 | 2.4 | 15,579 | 39 | 36.5 | |

| Hispanic Concentration (by county) | |||||||||

| Less than 5% Hispanic | 370 | 18 | 132,241 | 16 | 2.8 | 6,549 | 17 | 56.5 | |

| 5% – <10% Hispanic | 487 | 23 | 192,599 | 23 | 2.5 | 8,450 | 21 | 57.6 | |

| 10% – <20% Hispanic | 411 | 20 | 160,620 | 19 | 2.6 | 7,248 | 18 | 56.7 | |

| 20% or more Hispanic | 826 | 39 | 364,709 | 43 | 2.3 | 17,408 | 44 | 47.4 | |

New HIV diagnoses are considered as an ecological proxy for PrEP need per geographic area

Large central metro: greater than 1,000,000 population, central. Large fringe metro: greater than 1,000,000 population, fringe. Medium metro: between 250,000 and 999,999 population. Small metro: between 250,000 and 50,000 population. Micropolitan: between 10,000 and 49,999 population. Noncore: less than 10,000 population.

Table 2.

State-Level Distribution of PrEP-Providing Clinics by Total Population, PrEP Eligible MSM and New HIV Diagnoses

| PrEP-Providing Clinics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N per State |

Population1 | N per 100,000 Population |

PrEP- Eligible MSM Population |

N per 1,000 PrEP Eligible MSM |

New HIV Diagnoses2 |

N per 1,000 New HIV Diagnoses |

|

| Alabama | 10 | 4,082,821 | 0.2 | 7,928 | 1.3 | 533 | 18.8 |

| Alaska | 8 | 605,097 | 1.3 | 1,637 | 4.9 | 37 | 216.2 |

| Arizona | 47 | 5,761,526 | 0.8 | 20,500 | 2.3 | 778 | 60.4 |

| Arkansas | 7 | 2,479,841 | 0.3 | 3,653 | 1.9 | 314 | 22.3 |

| California | 322 | 32,715,033 | 1.0 | 134,968 | 2.4 | 4,961 | 64.9 |

| Colorado | 89 | 4,632,086 | 1.9 | 20,685 | 4.3 | 423 | 210.4 |

| Connecticut | 43 | 3,056,129 | 1.4 | 5,891 | 7.3 | 251 | 171.3 |

| Delaware | 8 | 806,543 | 1.0 | 2,449 | 3.3 | 117 | 68.4 |

| Florida | 139 | 17,661,830 | 0.8 | 77,093 | 1.8 | 4,940 | 28.1 |

| Georgia | 33 | 8,521,448 | 0.4 | 26,781 | 1.2 | 2,709 | 12.2 |

| Hawaii | 7 | 1,201,433 | 0.6 | 3,958 | 1.8 | 82 | 85.4 |

| Idaho | 7 | 1,369,530 | 0.5 | 3,058 | 2.3 | 44 | 159.1 |

| Illinois | 90 | 10,726,317 | 0.8 | 40,942 | 2.2 | 1,384 | 65.0 |

| Indiana | 33 | 5,506,076 | 0.6 | 13,537 | 2.4 | 483 | 68.3 |

| Iowa | 10 | 2,611,034 | 0.4 | 2,985 | 3.4 | 133 | 75.2 |

| Kansas | 17 | 2,389,068 | 0.7 | 3,577 | 4.8 | 141 | 120.6 |

| Kentucky | 17 | 3,714,599 | 0.5 | 9,486 | 1.8 | 319 | 53.3 |

| Louisiana | 33 | 3,878,595 | 0.9 | 9,404 | 3.5 | 1,151 | 28.7 |

| Maine | 25 | 1,151,311 | 2.2 | 2,371 | 10.5 | 50 | 500.0 |

| Maryland | 37 | 5,052,126 | 0.7 | 16,133 | 2.3 | 1,097 | 33.7 |

| Massachusetts | 54 | 5,845,108 | 0.9 | 13,198 | 4.1 | 710 | 76.1 |

| Michigan | 47 | 8,385,984 | 0.6 | 21,417 | 2.2 | 747 | 62.9 |

| Minnesota | 29 | 4,588,522 | 0.6 | 15,342 | 1.9 | 286 | 101.4 |

| Mississippi | 10 | 2,471,502 | 0.4 | 3,434 | 2.9 | 424 | 23.6 |

| Missouri | 31 | 5,101,456 | 0.6 | 13,653 | 2.3 | 511 | 60.7 |

| Montana | 6 | 878,537 | 0.7 | 2,106 | 2.9 | 17 | 352.9 |

| Nebraska | 5 | 1,562,564 | 0.3 | 1,857 | 2.7 | 76 | 65.8 |

| Nevada | 21 | 2,452,586 | 0.9 | 8,260 | 2.5 | 525 | 40.0 |

| New Hampshire | 9 | 1,152,702 | 0.8 | 2,011 | 4.5 | 42 | 214.3 |

| New Jersey | 44 | 7,537,589 | 0.6 | 15,496 | 2.8 | 1,143 | 38.5 |

| New Mexico | 17 | 1,733,137 | 1.0 | 5,317 | 3.2 | 125 | 136.0 |

| New Y ork | 255 | 16,745,354 | 1.5 | 49,896 | 5.1 | 2,875 | 88.7 |

| North Carolina | 52 | 8,513,324 | 0.6 | 22,582 | 2.3 | 1,404 | 37.0 |

| North Dakota | 5 | 626,443 | 0.8 | 765 | 6.5 | 46 | 108.7 |

| Ohio | 69 | 9,765,669 | 0.7 | 29,147 | 2.4 | 969 | 71.2 |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 3,225,510 | 0.3 | 7,894 | 1.0 | 293 | 27.3 |

| Oregon | 22 | 3,471,843 | 0.6 | 14,124 | 1.6 | 221 | 99.6 |

| Pennsylvania | 66 | 10,888,756 | 0.6 | 22,004 | 3.0 | 1,150 | 57.4 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 912,171 | 0.2 | 3,239 | 0.6 | 70 | 28.6 |

| South Carolina | 13 | 4,172,373 | 0.3 | 6,781 | 1.9 | 757 | 17.2 |

| South Dakota | 2 | 707,973 | 0.3 | 749 | 2.7 | 39 | 51.3 |

| Tennessee | 30 | 5,576,555 | 0.5 | 16,548 | 1.8 | 715 | 42.0 |

| Texas | 91 | 22,593,541 | 0.4 | 89,558 | 1.0 | 4,464 | 20.4 |

| Utah | 10 | 2,377,712 | 0.4 | 5,670 | 1.8 | 135 | 74.1 |

| Vermont | 15 | 540,664 | 2.8 | 1,113 | 13.5 | 8 | 1,875.0 |

| Virginia | 24 | 7,070,310 | 0.3 | 23,152 | 1.0 | 893 | 26.9 |

| Washington | 126 | 6,106,317 | 2.1 | 25,111 | 5.0 | 432 | 291.7 |

| West Virginia | 9 | 1,562,558 | 0.6 | 2,665 | 3.4 | 66 | 136.4 |

| Wisconsin | 20 | 4,865,079 | 0.4 | 10,400 | 1.9 | 224 | 89.3 |

| Wyoming | 2 | 481,302 | 0.4 | 989 | 2.0 | 20 | 100.0 |

Population counts include only persons at least 13 years of age.

New HIV diagnoses are considered as an ecological proxy for PrEP need per geographic area

Table 3.

Distribution of 996 PrEP-Providing Clinics in Cities in the United States, by Total Population, Eligible MSM and New Diagnoses

| PrEP-Providing Clinics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City1 | N per City |

Population2 | N per 100,000 Population |

PrEP- Eligible MSM Population |

N per 1,000 PrEP Eligible MSM |

New HIV Diagnoses3 |

N per 1,000 New HIV Diagnoses |

| Atlanta, Georgia | 25 | 4,592,379 | 0.5 | 21,588 | 1.2 | 1,722 | 14.5 |

| Austin, Texas | 9 | 1,596,561 | 0.6 | 11,167 | 0.8 | 308 | 29.2 |

| Baltimore, Maryland | 26 | 2,336,010 | 1.1 | 9,054 | 2.9 | 531 | 49.0 |

| Baton Rouge, Louisiana | 5 | 682,542 | 0.7 | 1,076 | 4.6 | 250 | 20.0 |

| Birmingham, Alabama | 2 | 950,171 | 0.2 | 3,717 | 0.5 | 106 | 19.0 |

| Bridgeport Areaa, Connecticut | 13 | 786,439 | 1.7 | 1,142 | 11.4 | 72 | 180.6 |

| Charlotte, North Carolina | 16 | 1,960,643 | 0.8 | 8,777 | 1.8 | 399 | 40.1 |

| Chicago, Illinois | 80 | 7,913,514 | 1.0 | 37,347 | 2.1 | 1,255 | 63.8 |

| Columbia, South Carolina | 5 | 671,446 | 0.7 | 1,191 | 4.2 | 178 | 28.1 |

| Dallas, Texas | 27 | 5,607,813 | 0.5 | 32,245 | 0.8 | 1,341 | 20.1 |

| Denver, Colorado | 48 | 2,275,974 | 2.1 | 16,145 | 3.0 | 302 | 159.1 |

| Detroit, Michigan | 25 | 3,605,463 | 0.7 | 12,684 | 2.0 | 504 | 49.6 |

| Hartford, Connecticut | 13 | 1,036,214 | 1.3 | 2,806 | 4.6 | 72 | 181.8 |

| Houston, Texas | 45 | 5,203,917 | 0.9 | 26,238 | 1.7 | 1,467 | 30.7 |

| Jackson, Mississippi | 1 | 134,485 | 0.7 | 183 | 5.5 | 11 | 90.9 |

| Jacksonville, Florida | 6 | 1,190,311 | 0.5 | 5,162 | 1.2 | 337 | 17.8 |

| Las Vegas, Nevada | 19 | 1,712,020 | 1.1 | 6,767 | 2.8 | 470 | 40.4 |

| Memphis, Tennessee | 13 | 1,096,682 | 1.2 | 5,647 | 2.3 | 303 | 42.9 |

| Miami Areab, Florida | 59 | 5,050,905 | 1.2 | 29,762 | 2.0 | 2,342 | 25.2 |

| Milwaukee, Wisconsin | 9 | 1,304,605 | 0.7 | 5,533 | 1.6 | 117 | 76.9 |

| Nashville, Tennessee | 6 | 1,484,647 | 0.4 | 6,793 | 0.9 | 187 | 32.1 |

| New Haven Areac, Connecticut | 10 | 734,856 | 1.4 | 1,099 | 9.1 | 81 | 123.5 |

| New Orleans, Louisiana | 21 | 1,045,421 | 2.0 | 5,055 | 4.2 | 422 | 49.8 |

| New York City Aread, New York | 200 | 16,859,126 | 1.2 | 50,878 | 3.9 | 3,401 | 58.8 |

| Norfolk Areae, Virginia | 5 | 1,433,906 | 0.3 | 5,421 | 0.9 | 298 | 16.8 |

| Orlando, Florida | 35 | 1,957,263 | 1.8 | 12,226 | 2.9 | 664 | 52.7 |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 46 | 5,086,489 | 0.9 | 11,700 | 3.9 | 793 | 58.0 |

| Raleigh, North Carolina | 11 | 1,019,379 | 1.1 | 4,942 | 2.2 | 189 | 58.3 |

| Richmond, Virginia | 6 | 1,058,667 | 0.6 | 3,888 | 1.5 | 181 | 33.1 |

| San Francisco Areaf, California | 82 | 3,897,873 | 2.1 | 29,413 | 2.8 | 739 | 111.0 |

| Seattle, Washington | 82 | 3,080,373 | 2.7 | 16,941 | 4.8 | 314 | 261.1 |

| Tampa, Florida | 13 | 2,500,138 | 0.5 | 17,143 | 0.8 | 559 | 23.3 |

| Washington, D.C.g | 33 | 4,990,502 | 0.7 | 25,579 | 1.3 | 1,110 | 29.7 |

Defined by core based statistical areas

Population counts include only persons at least 13 years of age

New HIV diagnoses are considered as an ecological proxy for PrEP need per geographic area

Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk CBSA

Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach CBSA

New Haven-Milford CBSA

New York City-Newark CBSA

Norfolk-Virginia Beach-Hampton Roads CBSA

San Francisco-Oakland-Alameda CBSA

Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, CBSA

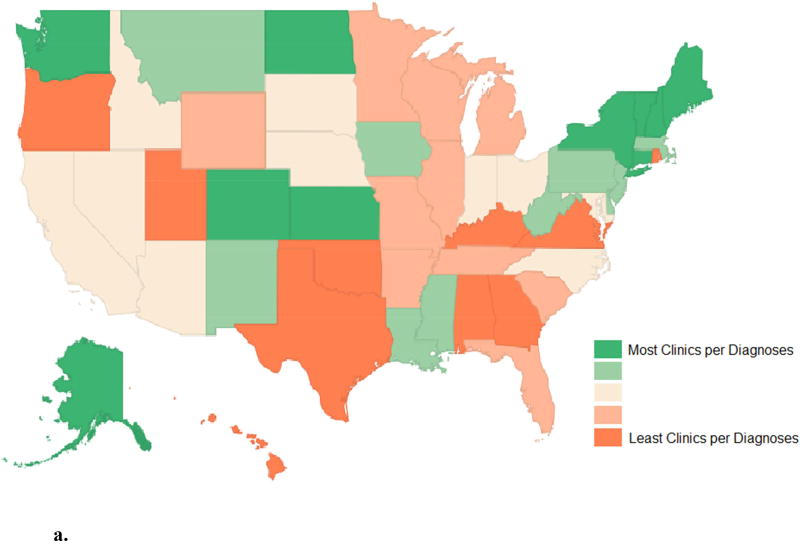

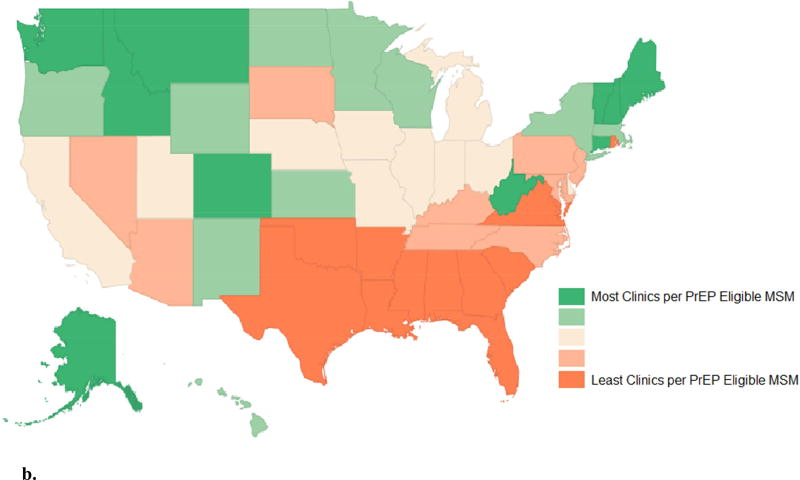

Figures 1a and 1b geographically present state-level data. Figure 1a displays clinic prevalence for each state, with states grouped by quintile (groups of 10 states) from least to greatest PrEP clinic prevalence. Figure 1b displays the ratio of clinics per 1,000 new HIV diagnosis in each state, with states grouped by quintile from least to greatest values.

Figure 1.

a. The proportion of PrEP-providing clinics per PrEP-eligible MSM by state, ranked by quintile 2018

b. The proportion of PrEP-providing clinics per new HIV diagnoses by state, ranked by quintile, 2018

Results

There were 2,094 publicly listed, PrEP-providing clinics in the United States (Table 1). Relative to need, estimated through concentration of new HIV diagnoses, Southern census divisions had fewer than expected PrEP clinics. Southern census divisions of the United States had lower ratios of PrEP-providing clinics to new HIV diagnoses than census divisions in other regions. For instance, the South Atlantic Division had 15.9% of all publicly listed PrEP clinics and 31.0% of all new HIV diagnoses. The Southern region, comprising all Southern census divisions (East South Central, West South Central, and South Atlantic), accounted for 51.7% of all new HIV diagnoses, but only 25.7% of PrEP-providing clinics. Analysis of counties, grouped by demographic characteristics, revealed disparities in the proportion of clinics relative to the number of new HIV diagnoses. Counties with ≥20% of the population living in poverty had 13.8% of PrEP-providing clinics, and 18.2% of new HIV diagnoses. Counties with ≥20% of the population lacking health insurance had 3.8% of clinics and 10.8% of new HIV diagnoses. Counties with ≥20% identifying as African American had 27.2% of PrEP-providing clinics and 39.3% of new HIV diagnoses.

PrEP-providing clinic prevalence (clinics per overall population), ratios of clinics per PrEP-eligible MSM, and ratios of clinics per new HIV diagnoses were low across states (Table 2). 43/50 states had <1 PrEP-providing clinic per 100,000 population, 1/50 states had <1 clinic per 1,000 PrEP-eligible MSM, and 35/50 states had <100 clinics per 1,000 new HIV diagnoses. No state had >3 PrEP-providing clinics per 100,000 population or >14 clinics per 1,000 PrEP eligible MSM.

There was substantial variation in the availability of PrEP across states. The median ratio of PrEP clinics per 100,000 overall population was 0.6 among all states, with a range that spanned over an order of magnitude (0.2 to 2.8). The median ratio of PrEP clinics per 1,000 PrEP-eligible MSM was 2.4 (range, 0.6 to 13.5). The median was ratio of PrEP clinics per new 1,000 new HIV diagnoses was 67.1, with a range that spanned over two orders of magnitude (12.2 to 1,875.0).

State-level geographic distributions of PrEP-providing clinics are displayed using a denominator of population in Figure 1a and a denominator of new HIV diagnoses in Figure 1b. The different denominators allow for a view of the level of PrEP-providing clinics per population (Figure 1a) and per epidemic need (Figure 1b). PrEP-providing clinic ratios per PrEP-eligible MSM and per new 1,000 HIV diagnoses were higher in the New England, Middle Atlantic, and Mountain districts of the United States and lower in the West South Central, East South Central, and South Atlantic districts (Figure 1). Analysis of city-level data reveal similar trends (Table 3). PrEP availability is lower in the Southern cities of Birmingham (19.0 clinics / 1000 new diagnoses), Atlanta (14.5/1000), and Jacksonville (17.8/1000) than in the Northeast cities of Philadelphia (58.8/1000) and New York (58.8/1000) or than in the Northwest cities of San Francisco (111.0/1000) and Seattle (261.1/1000).

Discussion

This study of publicly listed PrEP-providing clinics in the United States provides a geographic depiction of the availability of PrEP. PrEP-providing clinics were rare, with more than half of states having <3 PrEP-providing clinics per 1,000 PrEP-eligible MSM. For even a moderate proportion of MSM eligible for PrEP to be able to initiate care, the availability of PrEP-providing clinics will need to increase. To have optimal impact, PrEP coverage will need to be high; modeling indicates that 40% PrEP coverage among eligible MSM could prevent 33% of new HIV infections, with diminishing impact at lower coverage levels.(30) To achieve such levels of PrEP scale-up, new strategies are needed to increase access to PrEP.

Within the United States, several disparities in PrEP access emerge in this county-level analysis, including different numbers of clinics compared to region, income, ethnicity, and insurance status. The direction of the disparities contradicts need, with population groups with higher levels of HIV transmission having less access to PrEP services. Southern states, areas of lower income, areas with higher African American and Hispanic populations, and areas with less insurance coverage all represent areas disproportionately impacted by new HIV diagnoses,(31) and are conversely under-represented in PrEP clinic density. If not addressed, PrEP geographic and other access disparities may be sufficient to exacerbate existing disparities in the overall HIV epidemic in the United States. Therefore, there is a need to develop new strategies to make PrEP accessible not only more broadly, but also to those groups most at-risk who currently experience lower levels of access to health services.

PrEP is a new HIV intervention approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012, and the existence of 2,094 publicly listed PrEP-providing clinics in the United States is a noteworthy public health accomplishment. In our dataset, it is clear that local investments in PrEP have an impact in terms of access. Public health authorities in cities such as Seattle(32) and New York(33) have made concerted efforts to increase the number of publicly-listed PrEP-providing clinics, and the success of these efforts can be seen in the geographic distribution of clinics. Similarly, public health officials and groups in North Carolina have made successful outreach efforts to increase the number of local PrEP-providing clinics,(34) resulting in the state being an outlier to the trend of Southern states housing fewer PrEP providers. Localities also have the potential to alleviate disparities in PrEP provision due to income or insurance coverage by funding PrEP drug assistance and navigation programs that can facilitate increased PrEP access. These public health investments in PrEP yield clear benefits, and should be continued and expanded.

This study has a number of limitations. Clinics included in the dataset, coming from PrEP Locator, do not comprise all clinicians prescribing PrEP in the United States. Instead, clinics are those that were publicly listed and identified through an extensive search and vetting process. This results in underestimating the availability of PrEP-providing clinics. Yet, a substantial proportion (72% in one study)(35) of primary care providers had low familiarity with prescribing PrEP, so many patients seeking PrEP will be limited to publicly-listed PrEP clinics such as those in this study’s dataset. Using new HIV diagnoses from 2016, compared to PrEP clinic data from 2018, might introduce misclassification of characteristics of states, counties, or cities. Notably, CDC has recently indicated that new diagnoses decreased from 2008–2013 in the United States.(36) Ratios of PrEP-providing clinics to new HIV diagnoses may therefore be underestimated, although relative comparisons are likely still valid. Another limitation is that this analysis does not take into account clinic size. However, having fewer PrEP clinics overall, even if some may be larger or smaller, still likely serves as a barrier to seeking care. Last, access to a PrEP provider is not the sole barrier to PrEP use. An adequate distribution of PrEP-providing clinics would still not be sufficient to overcome other racial and economic disparities in PrEP access.(37, 38)

In the six years since the indication of TVD-FTC for PrEP by FDA, over 2,000 clinics have publicly listed themselves as providing PrEP. Despite this success, there is insufficient PrEP clinic availability, and local availability is in contradiction of need. Alternative models of PrEP provision may facilitate access, including provision of PrEP at pharmacies, federally qualified healthcare centers, and through telemedicine.(39, 40) Interventions to address disparities should also include structural interventions, such as Florida’s use of county-health clinics to provide PrEP at no-cost.(41) Such innovative programs and policies have the promise to decrease disparities in PrEP access, and to support continuation of the overall expansion of PrEP as a highly effective HIV prevention strategy.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Support for development of the PrEP Locator was provided by the MAC AIDS Fund. The study was facilitated by the Emory Center for AIDS Research P30AI050409 and by R01MH114692. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACS

American Community Survey

- CBSA

Core-Based Statistical Areas

- CDC

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- MSM

Men Who Have Sex with Men

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHSS

National HIV Surveillance System

- PEP

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

- PrEP

HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2014;14(9):820–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, Stryker JE, Hall HI, Prejean J, et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition--United States, 2015. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015;64(46):1291–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6446a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS (London, England) 2016;30(12):1973. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, Nguyen DP, Phengrasamy T, Silverberg MJ, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Large Integrated Health Care System: Adherence, Renal Safety, and Discontinuation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):540–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mera Giler R, Trevor H, Bush S, Rawlings K, McCallister S, editors. Changes in truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States:(2012–2016); 9th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.House W. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. Washington, DC: Office of the President of the United States; [accessed 10 August 2015]. 2015. https://aids. gov/federal-resources/nationalhiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update. pd. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(AVAC) AVAC. http://www.prepwatch.org/us-local-programs/

- 8.Sullivan PS, Sineath C, Kahle E, Sanchez T. AIDS Impact. Amsterdam: Jul, 2015. Awareness, willingness and use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among a national sample of US men who have sex with men. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman S, Guidry JA, Collier KL, Mantell JE, Boccher-Lattimore D, Kaighobadi F, et al. A clinical home for preexposure prophylaxis: diverse health care providers’ perspectives on the “purview paradox”. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC) 2016;15(1):59–65. doi: 10.1177/2325957415600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith DK, Mendoza MC, Stryker JE, Rose CE. PrEP awareness and attitudes in a national survey of primary care clinicians in the United States, 2009–2015. PLoS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement ME, Seidelman J, Wu J, Alexis K, McGee K, Okeke NL, et al. An educational initiative in response to identified PrEP prescribing needs among PCPs in the Southern US. AIDS care. 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1384534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang HL, Rhea SK, Hurt CB, Mobley VL, Swygard H, Seña AC, et al. HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Implementation at Local Health Departments: A Statewide Assessment of Activities and Barriers. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;77(1):72–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bacon O, Gonzalez R, Andrew E, Potter MB, Iniguez JR, Cohen SE, et al. Brief Report: Informing Strategies to Build PrEP Capacity Among San Francisco Bay Area Clinicians. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(2):175–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(9):1712–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0839-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings M, Hawkins T, McCallister S, Mera Giler R. Racial characteristics of FTC/TDF for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in the US. ASM Microbe/ICAAC. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herron PD. Ethical implications of social stigma associated with the promotion and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. LGBT health. 2016;3(2):103–8. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, Sanchez T, Del Rio C, Sullivan PS, et al. Applying a PrEP Continuum of Care for Men Who Have Sex With Men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;61(10):1590–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(2):226–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0675-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling Towards Disease: Transportation Barriers to Health Care Access. Journal of community health. 2013;38(5):976–93. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goswami ND, Schmitz MM, Sanchez T, Dasgupta S, Sullivan P, Cooper H, et al. Understanding local spatial variation along the care continuum: the potential impact of transportation vulnerability on HIV linkage to care and viral suppression in high-poverty areas, Atlanta, Georgia. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;72(1):65–72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014 clinical practice guideline. 2014 http://wwwcdcgov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014pdf.

- 22.Siegler AJ, Wirtz SS, Weber S, Sullivan PS. Developing a geolocated directory of PrEP-providing clinics: the PrEP Locator Protocol JMIR Res Protoc. 2017 doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7902. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emory University RSoPH. PrEP Locator. www.PrEPLocator.org.

- 24.Semega JL, Fontenot KR, Kollar MA. Income and poverty in the United States: 2016. Current Population Reports. 2017:10–1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett JC, Berchick ER. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016. US Government Printing Office; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. 2007 Published 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, Stryker JE, Hall HI, Prejean J, et al. Vital signs: estimated percentages and numbers of adults with indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(46):1291–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6446a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grey JA, Bernstein KT, Sullivan PS, Purcell DW, Chesson HW, Gift TL, et al. Estimating the Population Sizes of Men Who Have Sex With Men in US States and Counties Using Data From the American Community Survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(1):e14. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purcell D, Johnson C, Lansky A, Prejean J, Stein R, Denning P, et al., editors. Calculating HIV and syphilis rates for risk groups: estimating the national population size of men who have sex with men; National STD Prevention Conference; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenness SM, Goodreau SM, Rosenberg E, Beylerian EN, Hoover KW, Smith DK, et al. Impact of the Centers for Disease Control's HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Guidelines for Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016;214(12):1800–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health and selected HIV care outcomes among adults with diagnosed HIV infection in 32 states and the District of Columbia, 2014. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2016;21(7) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hood JE, Buskin SE, Dombrowski JC, Kern DA, Barash EA, Katzi DA, et al. Dramatic increase in preexposure prophylaxis use among MSM in Washington state. Aids. 2016;30(3):515–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler J, Myers JE, Nucifora KA, Mensah N, Toohey C, Khademi A, et al. Evaluating the impact of prioritization of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis in New York. Aids. 2014;28(18):2683–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.North Carolina AIDS Training and Education Center. Map of North Carolina PrEP Providers. 2017 Available from: https://www.med.unc.edu/ncaidstraining/prep/PrEP-for-consumers.

- 35.Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among US Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1256–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1625-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall HI, Song R, Tang T, An Q, Prejean J, Dietz P, et al. HIV Trends in the United States: Diagnoses and Estimated Incidence. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2017;3(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Kelley CF, Luisi N, Cooper HL, et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Annals of epidemiology. 2015;25(6):445–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G, Group NHBSS. Wortley P, et al. Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men—20 US Cities, 2014. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016;63(5):672–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcus JL, Volk JE, Pinder J, Liu AY, Bacon O, Hare CB, et al. Successful Implementation of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis: Lessons Learned From Three Clinical Settings. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2016;13(2):116–24. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegler A, Liu A, Mayer K, Thure K, Fish R, Andrew E, et al. 21st International AIDS Conference. Durban, South Africa: 2016. An exploratory assessment of the feasibility and acceptability of home-based support to streamline HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) delivery. (Accepted oral presentation). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baeten JM. Amplifying the Population Health Benefits of PrEP for HIV Prevention. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2018:jiy045-jiy. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]