Abstract

With the increase in asylum-related immigration since 2015, understanding how immigrants settle in a new country is at the centre of social and political debate in European countries. The objective of this study is to determine whether the necessary time to settle for Sub-Saharan Africa immigrants in France depends more on pre-migratory characteristics or on the structural features of the host society. Taking a capability approach, we define settlement as the acquisition of three basic resources: a personal dwelling, a legal permit of a least 1 year and paid work. We use data from the PARCOURS survey, a life-event history survey conducted from 2012 to 2013 that collected 513 life histories of Sub-Saharan African immigrants living in France. Situations regarding housing, legal status and activity were documented year by year since the arrival of the respondent. We use a Kaplan–Meier analysis and chronograms to describe the time needed for settlement, first for each resource (personal dwelling, legal permit and paid work) and then for the combined indicator of settlement. Discrete-time logistic regressions are used to model the determinants of this settlement process. Overall, women and men require 6 and 7 years (medians), respectively, to acquire basic resources in France. This represents a strikingly long period of time in which immigrants lack basic security. The settlement process varies according to gender, but very few sociodemographic factors influence settlement dynamics. Therefore, the length of the settlement process may be due to structural features of the host society.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10680-017-9463-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Settlement, Migration, Life-course approach, Sub-Saharan immigrants, France

Introduction

In 2016, 35.1 million people who were in Europe were born outside the EU-28. With the increase in asylum-related immigration since 2015, understanding how immigrants settle in a new country is at the centre of social and political debate in many European countries (Eurostat 2016).

The settlement process of immigrants arriving in a new country can be defined as the acquisition of resources in the host country (Castles et al. 2014b; Simon et al. 2015). As there are many kinds of resources, drawing on Amartya Sen’s capability approach, we focus here on those fundamental resources people need to be able to lead lives they can value (Sen 1999). A particularity of Sen’s approach is to widen the scope beyond income to encompass other resources that can be crucial to ensuring a person’s security. His approach has been used in migration studies to provide a richer understanding of human mobility and has shown that income growth, improved education and access to information in emigration countries increase people’s capabilities to migrate (de Haas 2009). However, to our knowledge, his approach has never been used to study the immigrant settlement process. From this perspective, the settlement process can be understood not only as access to income, but also as acquisition of basic resources: a personal dwelling in which to be safe, a resident permit to feel secure.

Many factors may influence the time it takes to acquire these basic elements: a personal dwelling, a resident permit of at least 1 year and paid work. These elements may depend on pre-migratory individual characteristics, such as one’s level of education, which is an important factor of immigrant integration into the labour market (Castagnone et al. 2014). However, both the economic context and immigration policy regime of the host country could also strongly influence the acquisition of resources; high unemployment rates and the difficulties in obtaining a resident permit could slow down the settlement process.

In this paper, we address the settlement process of African immigrants coming from Sub-Saharan Africa and arriving in France. Our research question is as follows: For these immigrants, does the necessary time to acquire the basic resources needed to settle in France depends more on individual characteristics (such as education level) or on the structural features of the host society?

Additionally, the settlement process and its determinants may be different according to gender. First, migration motives and circumstances may vary between men and women, with a more work-oriented migration for those coming mainly for family reasons (Morokvasic 1984; Houstoun 1984). This could result in a faster acquisition of a personal dwelling for women who are joining a family member, regardless of their pre-migratory characteristics. However, these gendered patterns are rapidly changing, with the feminization of labour migration and more and more women arriving alone in host countries (Beauchemin et al. 2013; Castles et al. 2014a). A second objective is therefore to investigate whether the determinants of settlement pathways are gender-specific in this population of African immigrants to France.

To answer these questions, we use data from the ANRS PARCOURS survey, a retrospective life-event history survey conducted in 2012–2013 among a random sample of 513 Sub-Saharan immigrants in the Paris greater area (247 men and 266 women) who arrived in France between 1972 and 2011. Detailed information was collected on immigrants’ trajectories in their home country and in France regarding education, work, family, relationships, legal status, health, etc. Taking a life-course approach, we describe and analyse the timing and determinants of this Sub-Saharan immigrants’ settlement process in France.

Background

Sub-Saharan Immigrants Living in France: A Heterogeneous Population

Although the first waves of emigration from Sub-Saharan Africa to France can be traced back to the nineteenth century, the upsurge in this process began in the seventies. According to the 2011 French census, immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa1 (mainly, but not only from Western Africa) represented 13% (733,217 people) of the total number of immigrants residing in France in 2011; this proportion was 2% in 1975 (INSEE 2012a). Whereas it started as a work-motivated and masculine immigration, women have recently represented 51% of Sub-Saharan African immigrants living in France, according to the 2011 census (INSEE 2012a). Sub-Saharan migration to France, which covers several decades, has seen significant feminization in recent years. The profiles of immigrants coming from Sub-Saharan Africa have changed, as those immigrants coming from the Sahel to France were reunited with their families. Additionally, migration from countries situated south of the Sahel has increased, with well-educated people seeking asylum in France due to troubled political or military situations in their countries (Beauchemin et al. 2015).

The diversity of arriving immigrants’ profiles parallels the evolution of the regulatory context. Indeed, the closing of French borders in 1974 was only the beginning of immigration policies which aimed at limiting the flow of immigrant coming to work, with subsequent laws restricting the conditions for entry into France while facilitating the expulsion of undocumented immigrants in the 1980s. Nevertheless, family reunification policies led to an increase of 177% in the proportion of Sub-Saharan women immigrants between 1975 and 1982 (Tardieu 2006). From 1986 onwards, immigration policies have added conditions for family reunification and accelerated expulsions of undocumented immigrants. A new set of laws ratified in 2006–2007 further limited the right to family reunification in France, in accordance with the European context (Block and Bonjour 2013). This resulted in an important decrease in resident permits granted for family reasons (Mazuy et al. 2014).

Thus, Sub-Saharan immigrants living in France constitute a heterogeneous population that is relatively well educated compared to immigrants from other regions, with 45% having attained a secondary level of education in 2008 (INSEE 2012c). However, these data from the French census may not accurately describe the most precarious segments of this population and could hide differences between the undocumented, less-educated segment of the population and the documented, more educated segment. The last available figures indicate that there are between 200,000 and 400,000 undocumented immigrants in France, including all nationalities; although entry flow estimates are controversial, there seems to be a consensus on the estimate of the stock (Commission d’enquête sur l’immigration clandestine 2006).

In general, Sub-Saharan immigrants in France experience difficult living conditions. For example, 42% of those living in a Sub-Saharan African household in France are beneath the national poverty line (INSEE 2012b, 217). They are also particularly affected by unemployment (16% for men, 20% for women) (INSEE 2012b).

As for the settlement process, although data on integration pathways are collected in France among holders of first resident permits, this does not include all immigrants.2 These data show that immigrants exhibit high residential mobility during their first year after obtaining a resident permit, as 43% moved during that year, mostly to escape temporary and urgent situations. The model of workers’ hostels (foyers de travailleurs) created after World War II applies only to a small minority of immigrants in France (Garcin 2011). Sub-Saharan immigrants are concentrated in urban areas, and 60% live in the greater Paris area (INSEE 2012a). Available data on employment among first resident permit holders confirm that they are very affected by unemployment and are concentrated in certain work sectors, such as construction and restaurants (Breem 2013). However, as these data are seldom given by region of origin, it is difficult to know to what extent they apply to Sub-Saharan immigrants. In the end, these data concern only first resident permit holders and so cannot be used to study legal status histories.

Settlement Pathways and Life-Course Approach

The question of settlement and its factors has been raised in previous research, in particular in the field of immigrant integration in the host country labour market. Existing theories place a different focus on the role of economic and social context in shaping immigrant trajectories.

The temporary occupational downgrading of immigrants upon arrival, followed by an improvement in their professional situation, is known as the U-shaped trajectory of occupational adjustment. This assimilation model has been verified in several empirical studies in the USA and in Spain (Akresh 2008; Simón et al. 2014). The MAFE survey confirmed the U-shaped pattern of occupational mobility among Sub-Saharan immigrants in European countries, and as the initial downgrading was also found to affect highly qualified Sub-Saharan immigrants, the concept of ‘brain waste’ was proposed to account for the fact that in many host countries, immigrants’ qualifications were underused (Toma et al. 2011; Mattoo et al. 2008).

However, among other schools of thought that challenge the assimilation theory, the segmented labour market theory (or dual market theory) predicts the lack of occupational assimilation over time. This challenge comes from the fact that the demand for low-skilled immigrant labour is structurally embedded in modern capitalist countries and that the labour market is divided into two segments: a primary segment that offers jobs with high wages and better working conditions and a secondary segment with low-paid, unstable and unskilled jobs (Piore 1979; Castles et al. 2014c). Some immigrants are trapped in the secondary segment, and the initial downgrading of their situation may be more permanent. Thus, this occupational downgrading could last, given the structure of the labour market, and not so much because of previous qualifications immigrants may have. Among Senegalese immigrants living in France, Italy and Spain, upward mobility was found to depend not only on a mix of individual characteristics (proficiency in the destination country’s language, reason for migrating), but also on the administrative status (Obucina 2013; Castagnone et al. 2014).

In other areas such as housing trajectories, individual life-course data that could account for immigrant housing trajectories and strategies are lacking in France. Many studies have examined the urban segregation phenomenon (South et al. 2005) and tried to understand the underlying mechanisms behind immigrant decisions about where to live. Although residential trajectories in the general population in France have been well studied (Stovel and Bolan 2004; Bonvalet et al. 2010), as have homeless immigrants’ residential trajectories (Dietrich-Ragon and Grieve 2017), to the best of our knowledge no study has investigated the specificity of Sub-Saharan immigrant residential trajectories in France.

The acquisition of a residence permit in the host country is one of the crucial turning points in an immigrant’s settlement. However, these legal status histories are quite difficult to collect, for obvious reasons: undocumented immigrants are less likely to participate in any survey, and they are even less prone to declare that they are undocumented for fear of being reported to the authorities (Larchanché 2012). As for the acquisition of resident permits, previous research has shown how few enter without a visa, and many people become ‘illegal’ only once they are legally in the host country (Genova 2002). Additionally, it is variations in context and immigration legislation that is the main factor behind the advent of irregularities (Vickstrom 2014).

Thus, previous research shows how both individual characteristics and context can play a major role in immigrant pathways in the host country, highlighting how agency and structure are interrelated in shaping immigrant trajectories. In addition, the literature review also shows some gaps in understanding immigrant trajectories beyond their occupational situation. The life-course approach is actually much less established in the subfield of research on immigrant settlement and integration than migration decision-making (de Valk et al. 2011). In recent years, however, empirical studies have used such a life-course perspective to study immigrant trajectories (Latcheva et al. 2011; de Valk et al. 2011; Kleinepier et al. 2015). Moreover, survey data collection efforts aim to capture the dynamics of migration, such as the MAFE survey, which focused on migration between Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe (Beauchemin and González-Ferrier 2011). Interestingly, one of its main findings is the importance of return migration: for example, two out of ten people returned to Senegal after 10 years’ residence in a European country (Flahaux et al. 2013). Overall, these studies underline the importance of examining entire individual trajectories rather than merely immigrants’ situation at a given time.

Data and Methods

The ANRS PARCOURS Survey

The ANRS PARCOURS is a retrospective life-event history survey that was conducted in 2012–2013 among 763 Sub-Saharan immigrants randomly sampled in primary healthcare facilities in the Paris metropolitan area (for full details of the study, see Desgrées du Loû et al. 2016).

The sampling frame was designed to include 118 primary healthcare facilities of the National Federation of Health Centres (FNCS) of the Paris metropolitan area and 9 healthcare facilities that deal specifically with vulnerable populations. In each participating facility, the eligibility criteria included all persons born in a Sub-Saharan African country, aged 18–59 years. During the survey, physicians invited all eligible persons to participate and collected their written consent. Professional interpreters were available on demand. The participation rate was 72%, resulting in a total of 763 participants, and we were able to verify that these had the same sociodemographic characteristics as non-respondents.3 Among participants, detailed information on migration history, socioeconomic conditions, legal situation and lifetime health was collected anonymously through a standardized life-event questionnaire (including a life-history calendar), which was administered in person by a trained professional interviewer independent of the clinic staff. The interview occurred in a private room at the clinic to ensure confidentiality. Each dimension of interest was documented for each year from birth until the time of data collection. Individual weights were computed to account for sampling design and non-participation. The study was approved by the French National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties (CNIL). The complete protocol is available online at http://ceped.org/parcours/protocol-en.pdf and is registered on Clinicl-trials.gov (NCT02566148).

Population of Interest for the Study of Settlement Pathways

Because our study focuses on the settlement process, we decided to take into account the people who arrived in France after 18 years of age and who had spent at least 1 year in France at the time of the survey. Our final sample consisted of 513 people. Table 1 provides a description of the surveyed population according to sex. Our study population is relatively old (median age 46 years for men and 45 for women), and 66% of men and 77% of women reached at least a secondary level of education. The respondents arrived between 1972 and 2011 (39% between 1972 and 1996, 35% between 1997 and 2004, and 26% between 2005 and 2011). The median duration of stay in France was 14 years for both men and women. Logically, the countries of origin most represented correspond to former French colonies or countries that were under French or Belgian influence until the 1960s, with more than 80% of the total sampled individuals coming from seven countries: Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Mali, Republic of the Congo and Senegal (data not shown).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of ANRS PARCOURS interviewees at time of survey, per sex (scope: people having arrived in France at age 18 or over, N = 513).

Source Parcours survey, 2012-2013

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 247 | N = 266 | ||||

| %pond | n | %pond | n | p men/women | |

| Age | |||||

| 18–34 | 17 | 49 | 25 | 71 | 0.1341 |

| 35–44 | 30 | 77 | 23 | 72 | |

| 45–60 | 54 | 121 | 53 | 123 | |

| Median (IQR) | 46 [37–52] | 45 [35–52] | |||

| Age at arrival | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 27 [23–32] | 26 [22–32] | |||

| Region of birth | |||||

| Western Africa | 67 | 168 | 52 | 141 | 0.0481 |

| Central Africa | 30 | 70 | 43 | 115 | |

| Eastern/Southern Africa | 3 | 9 | 5 | 10 | |

| Period of arrival | |||||

| 1972–1995 | 41 | 81 | 38 | 82 | 0.6872 |

| 1996–2004 | 33 | 85 | 37 | 97 | |

| 2005–2011 | 26 | 81 | 25 | 87 | |

| Conjugal status at arrival | |||||

| Alone | 56 | 138 | 34 | 95 | 0.0000 |

| Stable partner in France | 25 | 60 | 59 | 148 | |

| Stable partner abroad | 19 | 49 | 8 | 23 | |

| Migration motive | |||||

| Find a job/take a chance | 45 | 120 | 23 | 76 | 0.0000 |

| Family reasons | 12 | 29 | 45 | 110 | |

| Threatened in his/her country | 22 | 50 | 16 | 43 | |

| Study | 19 | 42 | 13 | 27 | |

| Medical reasons | 1 | 6 | 3 | 10 | |

| Educational level at arrival | |||||

| None/Primary | 34 | 83 | 23 | 63 | 0.0001 |

| Secondary | 42 | 106 | 61 | 161 | |

| Superior | 24 | 58 | 16 | 42 | |

| Residential situation at arrival | |||||

| Personal dwelling | 30 | 83 | 43 | 100 | 0.0195 |

| Hosted by relatives/relations | 45 | 105 | 44 | 119 | |

| Collective structures | 2 | 7 | 1 | 5 | |

| Residential instability | 22 | 52 | 12 | 42 | |

| Legal status at arrival* | |||||

| No legal permit | 46 | 120 | 33 | 98 | 0.0584 |

| Legal permit for less than a year | 33 | 69 | 40 | 100 | |

| Legal permit of at least 1 year | 20 | 51 | 25 | 62 | |

| French nationality | 2 | 7 | 2 | 6 | |

*Legal status at arrival is determined by the first episode of legal trajectory, independently of having a travel document or not.

Migration profiles differ between sexes: most men (56%) were single upon arrival in France, whereas 59% of women had a stable partner upon arrival. This is also reflected in migration motives, as 45% of women came for family reunification. Consequently, more men than women experienced instability upon arrival in France: 22% of men went through an episode of residential instability (often changing dwelling) versus 12% of women. Furthermore, 46% of men versus only 33% of women had no legal permit whatsoever at the beginning of their stay in France.

We found that 5% of our sample had complex migration trajectories in that they had migrated to France several times. Therefore, rather than letting the researcher subjectively decide which date should be considered their arrival in France, investigators asked respondents to indicate which date made more sense as the beginning of their settlement in France. Thus, we relied on the interviewee’s own perception of settlement (Lelièvre et al. 2009) and were able to include people with complex trajectories in our study.

Indicators of Settlement as Acquisition of Resources

To study immigrants’ settlement process, we constructed indicators of acquisition of the three types of aforementioned resources—independent housing, a legal permit and paid work—for each year since arrival until data collection.

Having Acquired a Personal Dwelling

We assumed that settlement was attained when individuals declared they had lived in a personal dwelling. The definition of a personal dwelling is a dwelling one considers one’s own, as a tenant or owner, in which he or she stayed for at least 1 year, as opposed to being hosted by someone, living in a charity venue or having no stable housing. It is important to note that workers’ hostels (foyers de travailleurs) constitute a typical means for Sub-Saharan immigrants to settle in France (Bernardot 2006, 2008). Thus, this type of housing is relevant to our analysis, and we consider it as a type of personal dwelling. Having obtained one’s first personal dwelling (yes/no for a given year) is our first indicator of settlement.

Having Acquired a Stable Residence Permit

The legal context of foreigners’ residence in France has evolved over recent decades, primarily in the restriction of conditions to obtain a resident permit for family reunification (which allows persons to work in France). These conditions, such as the knowledge of French language or resource conditions, entailed a drop in the number of permits granted for family reasons, although they still represented about half of the permits granted in 2012 (Mazuy et al. 2014). That same year, about a quarter of the permits were granted for educational reasons and 9% for humanitarian reasons. However, in 2012, approximately 90% of the newly granted permits were for less than 10 years.

To be undocumented is undoubtedly a difficult experience that hinders immigrants’ daily life. Holding a short-term permit (of less than 1 year) means frequent visits to the authorities and considerable uncertainty about legal residence for months or years. Furthermore, these short-term permits often do not grant immigrants the right to work. Thus, we chose to consider being granted a 1-year permit (or longer) as constituting basic security. Having obtained one’s first legal permit of at least 1 year (yes/no for a given year) is our second indicator of settlement.

Having Acquired an Income-Generating Activity

We assumed that, from a capability perspective, what matters is to be able to earn one’s own living. Under that definition, precarious or informal activities qualify as long as they provide stable economic resources for at least a year. Having obtained an activity that provides financial autonomy (yes/no for a given year) is our third indicator of settlement, which we name ‘paid work’ throughout the text.

In this particular analysis of occupational trajectories, we did not include people who came to France with a student visa, because employment relies on different dynamics. This criterion led us to exclude 39 men and 56 women who were students upon arrival. The population of interest is thus 418 persons.

Because the settlement process should be considered as a whole, we then built a combined indicator of settlement that incorporates the three indicators discussed above (the moment people have obtained a personal dwelling, a legal permit of at least 1 year and paid work).

Details of the life-history calendar regarding residence, legal status, activities and financial resources can be found in Online Appendix 1.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis of each of the three settlement indicators and of the combined indicator (i.e. the moment persons have obtained a personal dwelling, a legal permit of at least 1 year and paid work). Instead of representing the duration (survival) curves (S(t)) before the acquisition of each of our indicators, we preferred to display the cumulative distribution function ((F(t) = 1 − S(t)) and the medians per sex. To graphically illustrate the dynamics of settlement for each sex, we also present chronograms with the distribution of the different possible situations regarding housing, legal status and activity, each year after arrival in France.

The year-by-year hazard rates to acquire a personal dwelling, a legal permit of at least 1 year and paid work were modelled with discrete-time regression models, as was the combined indicator of having obtained the three resources. In all the models, we included variables that captured individual and migration characteristics. In particular, we included sociodemographic variables (region of origin—West Africa, Central Africa, East and Southern Africa), age at arrival in France, educational level at arrival in France) and arrival circumstances variables (period of arrival, marital status at arrival, migration motive, whether or not the person had lived in France before). The structural context in the host country at the time of arrival was informed by the variable ‘period of arrival’. In this context, we considered three different periods: (1) before 1996, (2) between 1996 and 2004, when Pasqua Laws restricted the conditions for family reunifications and for obtaining a resident card, and (3) 2005 and after, when a new set of laws increased the complexity of family reunification at the European level. The regressions were stratified per sex.

Third, to assess to what extent the three elements of settlement are intertwined, we computed three variables for each individual, each corresponding to the number of years before obtaining one of the elements. We then estimated a pairwise residual correlation matrix between these three variables using a linear marginal model.

Results

How Long Does it Take? Gendered Dynamics of Settlement

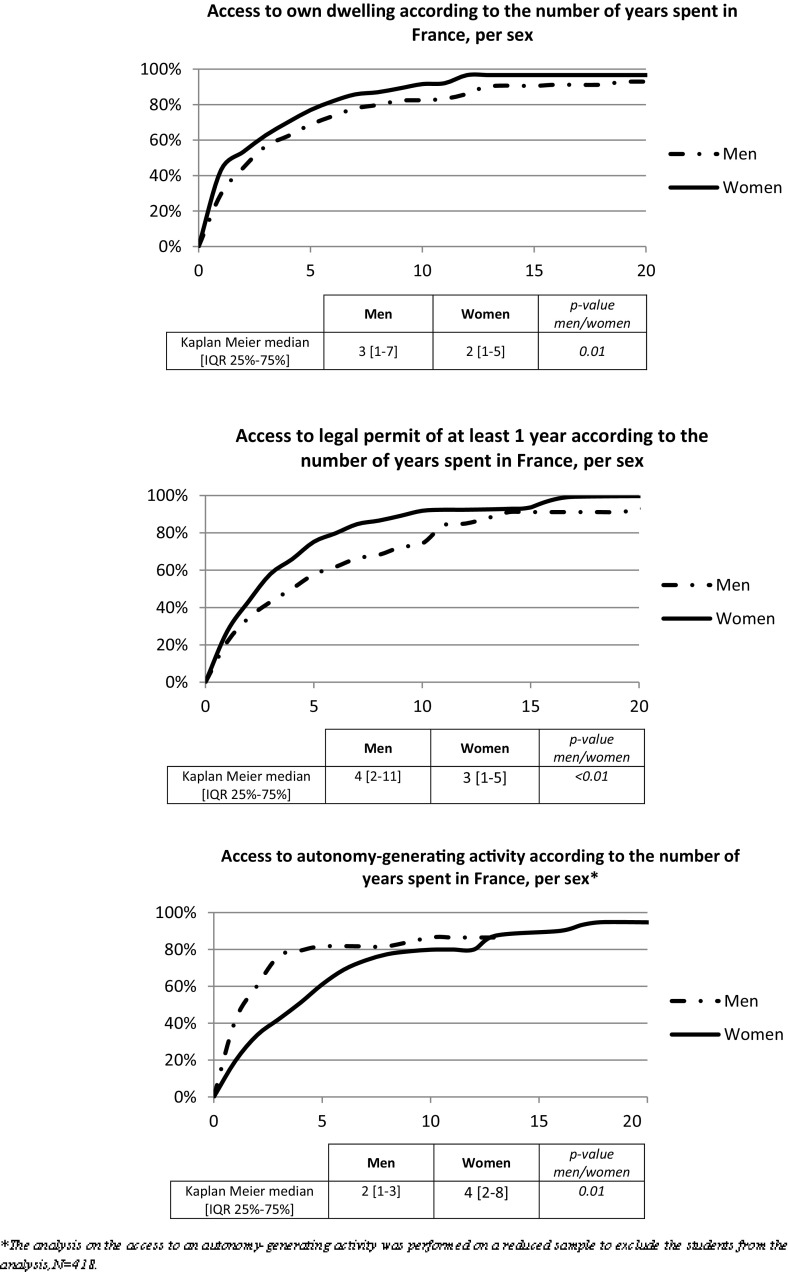

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier estimates for duration of stay in France before obtaining a personal dwelling, a legal permit of at least 1 year and paid work. It reveals the length of the settlement process and how the process differs for men and women.

Fig. 1.

Access to own dwelling, legal permit ≥ 1 year, autonomy-generating activity, according to the number of years spent in France, per sex (N = 513). Kaplan–Meier smoothed survival curves and medians. Reading note the medians represent the sojourn-in-France year ranking. A median of 3 for personal dwelling means: for this category of persons, half of them have obtained a personal dwelling during their third year in France.

Source: ANRS Parcours survey, 2012–2013

Half of the Sub-Saharan immigrant women obtained a personal dwelling during their second year in France and men during their third year (medians, p = 0.01). This finding must be understood in relation to the important proportion of women migrating to France for family reasons, as seen previously (45%, see Table 1), and therefore joining the residence already secured by their partner. Interestingly, some differences exist between arrival cohorts. Women who arrived more recently have less often come to join a family member, and therefore, it takes them more time to actually find their own dwelling: 3 years in median for women arriving between 2005 and 2011, versus 1 year for those arriving before 1996. Notably, 24% of men found a personal dwelling in a workers’ hostel versus 7% of women (p < 0.01). The duration of stay in workers’ hostels is also quite different between men and women: men stay an average of 7 years, whereas women only stay for 2 years (data not shown). Thus, staying in a workers’ hostel is a frequent trend for men, as previously shown in the literature (Bernardot 2006, 2008). For women, it seems to be more of a temporary accommodation.

There is also a gender difference in acquiring a legal permit of at least 1 year. Women obtain the permit during the third year (median), whereas men obtain it in the fourth year (p < 0.01). Additionally, the necessary time to acquire the legal permit is longer for men in the recent years (4 years before 1996 in median vs. 6 years for those arrived after 2005), whereas it is stable for women. Family reunification undoubtedly explains why acquiring a legal permit was faster for women.

Finally, men obtain paid work more quickly: during their second year in France, in median. The process takes somewhat longer for women (during their fourth year). A high proportion of people acquire their first paid work through precarious jobs: 35% of men and 20% of women (p < 0.06). The median length of this period of instability lasts 3 years [IQR 2–6] for women and 4 years [IQR 2–12] for men. Additionally, one man out of four experiences a period of precarious work that lasts more than a decade.

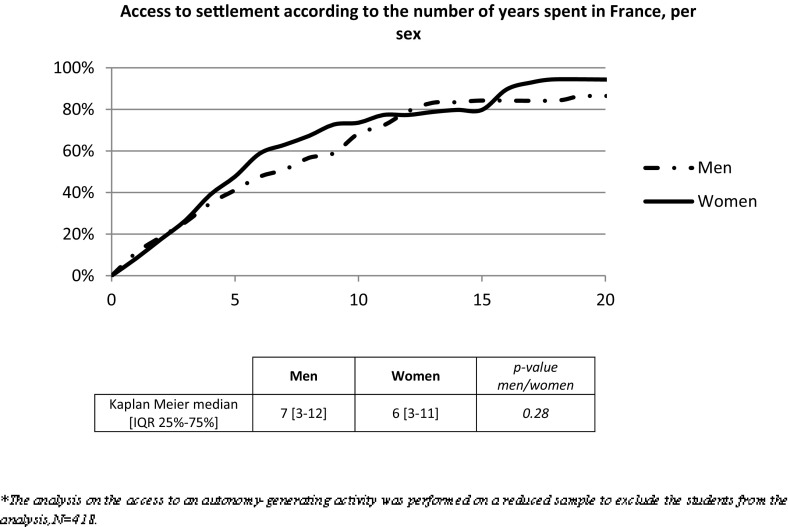

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier estimates for duration in France before acquiring the three resources, i.e. obtaining a personal dwelling, a legal permit of at least 1 year and a paid work.

Fig. 2.

Access to first settlement (cumulative indicator: own dwelling, legal permit ≥ 1 year, autonomy-generating activity) according to the number of years spent in France, per sex (N = 418*). Kaplan–Meier smoothed survival curves and medians.

Source: ANRS Parcours survey, 2012–2013

What is striking is the length of the settlement process. Despite the fact that we voluntarily chose ‘basic capability indicators’, it takes immigrants a median of 6 years for women and 7 years for men to reach basic security in terms of obtaining their own housing, legal status and paid work. This finding indicates that Sub-Saharan immigrants experience an extremely long period of insecurity before they are settled in France.

Looking at the different arrival cohorts reveals a probable lengthening of the settlement process in the different years, especially among men, although it is too soon to calculate the medians for the whole settlement process for persons arriving after 2005. However, among men the necessary time to obtain each element of settlement increased after 2005, in particular the time it took to obtain a legal permit of at least 1 year. It is somewhat different for women, because if the necessary time to find their own dwelling increased, the time to find paid work decreased; thus, these two indicators could compensate for each other.

Looking subsequently at different dimensions of settlement also allows us to detect a gender difference in the settlement process. For men, the process seems to be (1) paid work, (2) personal dwelling and (3) legal permit of at least 1 year. This process corresponds to settlement via the labour market. For women, the settlement process begins with (1) personal dwelling, then (2) legal permit of at least 1 year and ends with (3) paid work. This process applies to a greater proportion of women coming for family reunification in France. Although the duration of the settlement process is quite similar for men and women, the settlement process differs according to gender.

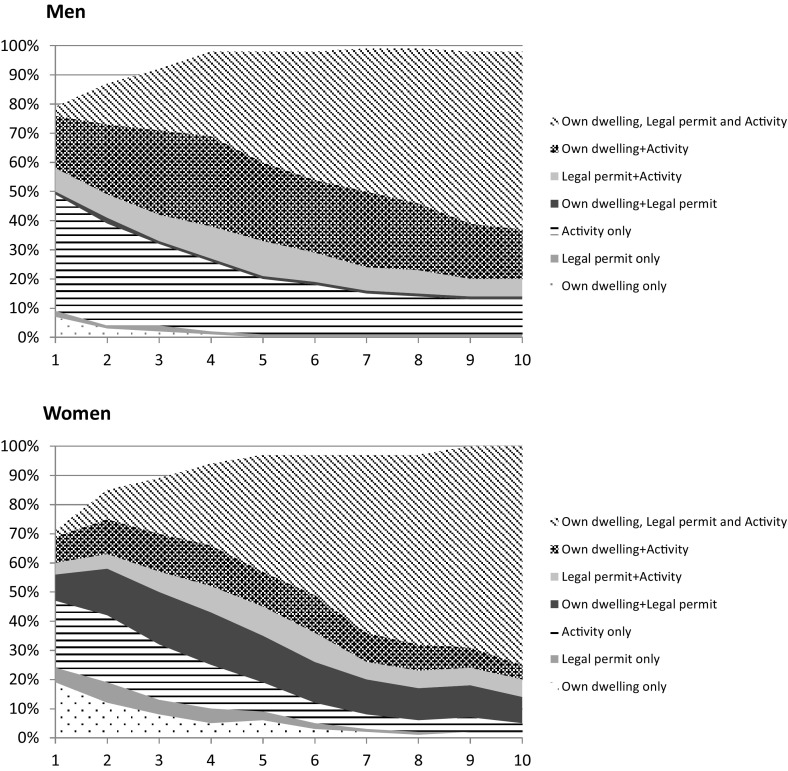

Figure 3 represents the proportion of immigrant men and women in each situation year by year as they advance in the settlement process. Differences between men and women are salient. An important portion of men begin settlement with a long period during which they work and are financially independent, but have neither a personal dwelling nor a legal permit of at least 1 year. The latter situation is less frequent for women, but does exist. These chronograms reveal the actual diversity of settlement trajectories, in particular among women. Some of them start in France with only their own dwelling, most likely moving in with a family member. Yet nearly the same proportion starts in France with paid work, as with the majority of men. Overall, the vast majority of these women have a paid activity in France after 7 years, whatever their migration motive.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of migrants who have obtained one, two or three elements of integration, according to the time spent in France, per sex (N = 418).

Source: ANRS Parcours survey, 2012–2013

Individual Characteristics and Structural Context: What Matters More?

Table 2 gives the results for discrete-time regressions on the probability by year of men and women obtaining a personal dwelling, a legal permit of at least 1 year and paid work, followed then by the probability of having acquired all three resources.

Table 2.

Factors for Sub-Saharan migrant integration in France, per sex (N = 418) (discrete-time regressions, coefficients presented as Odds ratios)

| Men (N = 208) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | First access to own dwelling | First access to legal permit ≥ 1 year | First access to autonomy-generating activity | First access to settlement (combined indicator) | |

| Time since arrival in France | 0.87 [0.81, 0.95] | 1.02 [0.97, 1.07] | 0.61 [0.49, 0.76] | 1.04 [0.99, 1.10] | |

| Period of arrival | |||||

| Before 1996 (ref) | 38 | 1.00 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| 1996–2004 | 36 | 0.69 [0.42, 1.13] | 0.85 [0.55, 1.33] | 0.82 [0.42, 1.60] | 0.88 [0.57, 1.34] |

| 2005–2011 | 26 | 0.55 [0.28, 1.08] | 0.80 [0.39, 1.65] | 0.32 [0.16, 0.64] | 0.61 [0.27, 1.36] |

| Region of birth | |||||

| Western Africa (ref) | 71 | 1.00 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Central. E and S Africa | 29 | 0.77 [0.46, 1.30] | 1.15 [0.63, 2.09] | 0.99 [0.52, 1.89] | 0.87 [0.48, 1.57] |

| Age at arrival | |||||

| 18–27 (ref) | 47 | 1.00 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| 28+ | 53 | 0.73[0.48, 1.14] | 0.72 [0.46, 1.11] | 0.75 [0.41, 1.39] | 0.65 [0.42, 1.02] |

| Educational level at arrival | |||||

| None/Primary (ref) | 40 | 1.00 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Secondary | 41 | 1.32 [0.75, 2.34] | 1.57 [0.90, 2.75] | 1.31 [0.69, 2.50] | 1.86 [1.04, 3.31] |

| Superior | 19 | 2.19 [1.03, 4.64] | 3.07 [1.48, 6.36] | 1.93 [0.77, 4.87] | 4.15 [1.86, 9.24] |

| Marital status at arrival | |||||

| Alone (ref) | 53 | 1.00 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Stable partner in France | 27 | 1.85 [1.06, 3.21] | 1.57 [0.94, 2.64] | 0.88 [0.43, 1.77] | 1.61 [0.96, 2.68] |

| Stable partner abroad | 19 | 0.97 [0.54, 1.73] | 0.90 [0.52, 1.55] | 1.07 [0.51, 2.21] | 0.88 [0.47, 1.63] |

| Migration motive | |||||

| Family reasons + medical (ref) | 63 | 1.00 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Find a job/take a chance/studies | 13 | 0.98 [0.55, 1.74] | 1.40 [0.80, 2.46] | 1.09 [0.46, 2.58] | 1.02 [0.58, 1.80] |

| Threatened in his/her country | 24 | 0.92[0.46, 1.82] | 1.10 [0.54, 2.21] | 0.79 [0.34, 1.86] | 0.92 [0.49, 1.75] |

| Already lived in France before | 3 | 1.11 [0.43, 2.90] | 4.98 [1.89, 13.11] | – | 1.83 [0.73, 4.59] |

| Women (N = 210) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | First access to own dwelling | First access to legal permit ≥ 1 year | First access to autonomy-generating activity | First access to settlement (combined indicator) | |

| Time since arrival in France | 0.90 [0.83, 0.98] | 1.01 [0.95, 1.07] | 0.93 [0.88, 0.98] | 1.04 [1.00, 1.08] | |

| Period of arrival | |||||

| Before 1996 (ref) | 36 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| 1996–2004 | 38 | 0.70 [0.40, 1.20] | 1.02 [0.64, 1.63] | 0.74 [0.40, 1.34] | 0.86 [0.55, 1.34] |

| 2005–2011 | 26 | 0.35 [0.18, 0.67] | 1.21 [0.69, 2.14] | 0.42 [0.21, 0.87] | 0.61 [0.32, 1.18] |

| Region of birth | |||||

| Western Africa (ref) | 50 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Central. E and S Africa | 50 | 0.88 [0.52, 1.49] | 0.87 [0.57, 1.33] | 0.66 [0.40, 1.08] | 0.77 [0.49, 1.21] |

| Age at arrival | |||||

| 18–27 (ref) | 45 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| 28+ | 55 | 1.16 [0.70, 1.92] | 0.97 [0.65, 1.45] | 0.93 [0.57, 1.51] | 0.95 [0.60, 1.49] |

| Educational level at arrival | |||||

| None/Primary (ref) | 27 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Secondary | 58 | 1.09 [0.62, 1.91] | 0.79 [0.46, 1.34] | 2.24 [1.27, 3.97] | 1.51 [0.87, 2.62] |

| Superior | 13 | 1.65 [0.62, 4.38] | 0.68 [0.28, 1.63] | 5.47 [2.39, 12.53] | 2.02 [0.80, 5.11] |

| Marital status at arrival | |||||

| Alone (ref) | 32 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Stable partner in France | 59 | 2.28 [1.40, 3.72] | 1.70 [1.02, 2.82] | 0.77 [0.40, 1.50] | 1.48 [0.90, 2.42] |

| Stable partner abroad | 9 | 0.70 [0.35, 1.41] | 0.87 [0.38, 2.01] | 0.67 [0.27, 1.69] | 1.04 [0.51, 2.13] |

| Migration motive | |||||

| Family reasons + medical (ref) | 31 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

| Find a job/take a chance/studies | 50 | 0.83 [0.51, 1.35] | 0.97 [0.59, 1.58] | 2.19 [1.18, 4.07] | 1.60 [1.04, 2.47] |

| Threatened in his/her country | 20 | 0.55 [0.29, 1.03] | 0.54 [0.27, 1.07] | 2.54 [1.33, 4.84] | 1.05 [0.52, 2.10] |

| Already lived in France before | 3 | 0.98 [0.38, 2.54] | 0.89 [0.38, 2.09] | 0.96 [0.42, 2.18] | 0.98 [0.38, 2.50] |

Adjusted Odds ratios, *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01

Source: PARCOURS survey, 2012–2013

Among men, we notice a strong educational gradient: the higher the qualification of the man upon arrival, the faster he acquires each of the three resources. This effect is particularly important regarding the acquisition of a legal permit of at least 1 year (OR superior level = 3.07 [1.48, 6.36]). Regarding the family situation, having a stable partner in France upon arrival is logically associated with faster acquisition of a personal dwelling. On the other hand, the recent period (2005–2011) hinders the acquisition of paid work (OR 0.32 [0.16–0.64]).

Among women, we notice a strong negative effect of having arrived during the more recent period (2005–2011) on the process of settlement (OR 0.35 [0.18–0.67] for the acquisition of one’s own dwelling; 0.42 [0.21–0.87] for acquisition of paid work). Our results highlight worsening living conditions for female newcomers. Slower acquisition of a personal dwelling could be due in part to the exacerbation of the housing crisis in the Paris metropolitan area. The more difficult acquisition of paid work seems to reflect the economic crisis, which may have had an impact not only on the male, but also the female employment sectors. Activity is much more dependent on individual characteristics for women than it is for men. Along with the motives for migrating, education actually plays an important role in finding a job (OR 2.24 [1.27–3.97] for secondary level, OR 5.47 [2.39–12.53] for superior level). Thus, individual characteristics seem to play an important role in women’s acquisition of paid work. However, even if education and migration motives play a role, a negative effect of the recent arrival period remains.

For the combined indicator, the different settlement dimensions tend to compensate for one another, which results in the absence of strong differentiation among immigrants: settlement appears to be a long process for anyone coming to France from Sub-Saharan Africa, whatever their profile. For men, higher education accelerates settlement (OR superior level = 4.15 [1.86, 9.24]); for women, the only factor that remains significantly associated with settlement is the migration motive (OR find a job/studies/take a chance = 1.60 [1.04–2.47]), which is probably being driven by a faster acquisition of paid work for women arriving independently. Although Sub-Saharan immigrants have different individual characteristics, they experience a similarly long process of settlement in France. Hardly any individual characteristic offers protection against the long period during which Sub-Saharan immigrants lack basic security. Moreover, the period of arrival, which reflects the context in which the persons arrive, seems to influence several dimensions of settlement. As a matter of fact, the recent period is associated with slower acquisition of paid work for men and slower acquisition of one’s own dwelling and paid work for women. This finding could be due both to the tightening of immigration laws (in particular the restriction of access to residence cards) and the economic crisis, which began in 2008. This recent period is also associated with slower acquisition of the combined indicators (OR 0.61 for both sexes), although the correlation is not significant. We probably lack the statistical power to demonstrate the negative effect of this recent period on the whole process of settlement.

Table 3 gives the correlation coefficients among the three elements of settlement with their 95% confidence intervals. These coefficients are all positive and significant, clearly showing that the three settlement dimensions are linked. The strongest correlation is between acquisition of a legal permit and personal dwelling (coef = 0.51 [0.41–0.60]). Acquiring one element helps accelerate the acquisition of another; settlement is a multidimensional process.

Table 3.

Correlations between the three elements of integration.

Source: PARCOURS survey, 2012–2013

| Correlation coefficients | IC95% | |

|---|---|---|

| First personal dwelling–first legal permit | 0.51 | [0.41–0.60] |

| First personal dwelling–first autonomy-generating activity | 0.30 | [0.19–0.41] |

| First legal permit–first autonomy-generating activity | 0.26 | [0.14–0.36] |

These correlations coefficients have been adjusted for time of observation

Discussion

This study of Sub-Saharan immigrants’ settlement process based on longitudinal data allowed us to show that 6–7 years are necessary to obtain a minimal set of resources that are essential for their further integration trajectories in France. The road to settlement has many pitfalls and few factors are found to be protective, except for the education of men, which means that few immigrants can avoid experiencing a long period of insecurity upon their arrival in France.

The housing market in the Paris greater area is known to be in structural crisis: in 2014, 950,000 persons were in a critical situation regarding housing in the region (homeless or living in substandard dwellings) due to high cost of housing, the scarcity of available homes or discrimination in access to the housing market (Abbé Pierre Foundation 2015). Immigrants also encounter numerous difficulties when entering the labour market. Some legal restrictions exist: those requesting a legal permit for professional reasons can be turned down on the grounds that unemployment rates are too high (Jolly et al. 2012). Discrimination during recruitment processes was found to be high in a recent empirical study (Petit et al. 2013). Discrimination is indeed a key determinant of the length of the settlement process, which has been measured in France in previous studies and which most persons surveyed link to ethnic and racial issues (Beauchemin et al. 2010; Brinbaum et al. 2015).

Thus, a segmented labour market hit by the economic crisis, a structural crisis in the housing market in the Paris greater area and restrictive migratory policies can explain why it takes time for immigrants to find their own place to live, to obtain a legal resident permit of at least 1 year and to find paid work.

Our study has some limitations. First, the random sampling occurred in healthcare facilities, which could have entailed a certain selection bias, as women generally tend to have more contact with the healthcare system, as well as older persons (Or et al. 2009). There were slightly more women (57 vs. 50%) and slightly more persons aged 45–59 years (26 vs. 20%) than in the census. However, the proportion of women and older persons in PARCOURS are very close to the Sub-Saharan population sampled in the TeO survey (Trajectories and Origins, Survey on Population Diversity in France, 2008), a nationally representative survey. If there is a selection bias, it is limited and does not invalidate our results. Moreover, in healthcare settings we were able to collect detailed residence permit histories, whatever the person’s legal status, because participants trusted in the complete confidentiality inherent in these settings. In France, health services constitute one of the only places where such data can be collected without the interviewees fearing to declare their illegal status. In this regard, the PARCOURS survey provides unique data on immigrants who do not necessarily participate in other surveys.

Second, immigrants were all recruited in the greater Paris metropolitan area; however, some aspects of the settlement process may be different in other parts of the country. For instance, the housing market situation may differ in other regions, which could impact on immigrants’ acquisition of their own dwelling. The logic of legal permit granting could also vary across regions in France. However, as 60% of Sub-Saharan immigrants in France live in that region, we still believe that our results paint an accurate picture of what the settlement process is similar to the majority.

Third, because the interviewees were recruited while living in France, the survey under-represents immigrants who returned to their country of origin or left for another destination after their stay in France. However, this selection bias (1) is inherent to all surveys collected in the country of arrival and (2) could go in two directions because two types of immigrants are absent from our survey: those who were unable to settle down because of social difficulties and those who returned to their country after a successful experience. These two types of biases may cancel each other out.

The retrospective nature of the data could also be discussed, as people are asked to retrace events that can have occurred several decades before the time of the survey. Memory biases impact all kinds of retrospective data collection; however, the use of life-event calendars was shown to limit these biases, as they make the persons date the events in relation to one another, using both dates and the person’s age as markers, guaranteeing a good robustness of the data (Courgeau 1991).

Finally, our study does not take into account trajectories with potential ‘steps backwards’ because we focus on indicators of the ‘first attainment’. However, both the previous literature on Sub-Saharan immigrant trajectories in Europe (Castagnone et al. 2014; Vickstrom 2014) and data from the PARCOURS survey (Gosselin, Desgrées du Loû, and Pannetier [forthcoming]) converge towards the idea that instability occurs at the beginning of the trajectory. Thus, examining the first acquisition of resources remains a meaningful way to describe and understand integration pathways.

Our study brings to light not only new empirical elements on the length of the settlement process and its correlates, but also on the interdependency of different dimensions: legal status, employment and housing issues are deeply connected in individual trajectories. Taking a capability approach perspective to the study of settlement led us to consider these different dimensions of the process, and taking a life-course approach led us to study the timing of acquisition of resources and the interdependency of the three resources under consideration. In addition, our results show how strongly the structural context (mostly economic crisis and tightening of immigration policies) shapes individual immigrants’ trajectories. Although the Sub-Saharan immigrant population is very diverse in origin, level of education and circumstances of migration, one of the most striking results of our study is that they almost all individuals go through a long period of insecurity and social hardship in France and that this process has become even more difficult in recent years: the best explanation is that the economic crisis and the tightening of immigration laws in France have affected the Sub-Saharan immigrant population arriving in the country and the conditions of their settlement.

This context may be comparable to other European countries, even more so since the arrival of refugees from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East fleeing war-torn countries. The economic crisis has hit Europe generally, and most countries have increasingly restrictive immigration policies (Block and Bonjour 2013). Thus, our results question current settlement policies put in place by European countries, as the arrival context is a strong determinant of people’s ability to settle.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Aknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the persons who participated in the study, the RAAC-Sida, COMEDE, FORIM and SOS hepatitis associations for their support in preparing and conducting the survey, G Vivier (INED) and A Gervais (AP-HP) for their support in preparing the questionnaire, H. Panjo for statistical support, A Guillaume for communication tools, the ClinSearch and Ipsos societies for data collection and staff at all participating centres.

The PARCOURS Study Group

The PARCOURS Study Group included A Desgrées du Loû, F Lert, R Dray Spira, N Bajos, N Lydié (scientific coordinators), J Pannetier, A Ravalihasy, A Gosselin, E Rodary, D Pourette, J Situ, P Revault, P Sogni, J Gelly, Y Le Strat, N Razafindratsima.

Funding

This study was supported by the French National Agency for research on AIDS and Viral hepatitis (ANRS) and the General Directorate of Health (DGS, French Ministry of Health). The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the paper.

Footnotes

To preserve people’s privacy, the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) does not provide numbers or characteristics for very small populations. The aggregated data exist for ‘Other African countries’, i.e., Africa, excluding Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. It is thus a good proxy for Sub-Saharan Africa.

The survey concerns immigrants who signed the Contrat d’Accueil et d’Intégration created in 2006, which immigrants sign when they obtain their first resident permit in France (now Contrat d’Intégration Républicaine). Several categories of persons are not included and do not have to sign that contract, including students, persons with a permit for healthcare reasons, persons coming for trade, industrial or handcraft work.

We compared participants and non-respondents according to sex, age and professional situation.

References

- Akresh IR. Occupational trajectories of legal US immigrants: Downgrading and recovery. Population and Development Review. 2008;34(3):435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00231.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, C., Borrel, C., & Régnard, C. (2013). Immigrants in France: A female majority. Population and Societies, 502. https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/19170/population_societies_2013_502_immigrants_women.en.pdf.

- Beauchemin C, González-Ferrier A. Sampling international migrants with origin-based snowballing method: New evidence on biases and limitations. Demographic Research. 2011;25:103–134. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, C., Hamel, C., Lesné, M., Simon, P., & Teo Survey Team. (2010). Discrimination: A question of visible minorities. Population and Societies, 466. https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/19134/pesa466.en.pdf.

- Beauchemin C, Lhommeau B, Simon P. Histoires migratoires et profils socioéconomiques. In: Beauchemin H, Simon, editors. Trajectoires et Origines. Enquête sur la diversité des populations en France. Paris: Ined; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardot M. Les foyers de travailleurs migrants à Paris. Voyage dans la chambre noire. Hommes & Migrations. 2006;1264:57–67. doi: 10.3406/homig.2006.4527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardot, M. (2008). Loger les immigrés. La Sonacotra 1956–2006. Editions du Croquant. Collection Terra. Broissieux.

- Block L, Bonjour S. Fortress Europe or Europe of rights? The Europeanisation of family migration policies in France, Germany and the Netherlands. European Journal of Migration and Law. 2013;15(2):203–224. doi: 10.1163/15718166-12342031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvalet, C., & Bringé, A. (2010). Les trajectoires socio-spatiales des Franciliens depuis leur départ de chez les parents. Temporalités, no [En ligne, 11]. http://temporalites.revues.org/1205.

- Breem, Y. (2013). L’insertion professionnelle des immigrés et de leurs descendants en 2011. Infos migrations, 48.

- Brinbaum Y, Safi M, Simon P. Les discriminations en France: entre perception et expérience. In: Beauchemin H, Simon, editors. Trajectoires et Origines. Enquête sur la diversité des populations en France. Paris: Ined; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Castagnone E, Nazio T, Bartolini L, Schoumaker B. Understanding transnational labour market trajectories of African-European migrants: Evidence from the MAFE survey. International Migration Review. 2014;49(1):200–231. doi: 10.1111/imre.12152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2014a). Introduction. In The age of migration. International population movements in the modern world (5th ed., pp. 1–22). Palgrave and Macmillan.

- Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2014b). New ethnic minorities and society. In The age of migration. International population movements in the modern world (5th ed., pp. 264–294). Palgrave and Macmillan.

- Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2014c). Theories of migration. In The age of migration. International population movements in the modern world (5th ed., pp. 25–53). Palgrave and Macmillan.

- Courgeau D. Analyse des données biographiques erronées. Population. 1991;46(1):89–104. doi: 10.2307/1533611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich-Ragon P, Grieve M. On the sidelines of French society. Homelessness among migrants and their descendants. Population. 2017;72(1):7–38. doi: 10.3917/popu.1701.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- du Loû D, Annabel JP, Ravalihasy A, Le Guen M, Gosselin A, Panjo H, Bajos N, et al. Is hardship during migration a determinant of HIV infection? Results from the ANRS PARCOURS study of sub-saharan African migrants in France. AIDS. 2016;30:645–656. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. (2016). Migration and migrant population statistics—statistics explained. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics#Migrant_population.

- Flahaux, M. L., Beauchemin, C., & Schoumaker, B. (2013). Partir, revenir: un tableau des tendances migratoires congolaises et sénégalaises». In Migrations africaines: le codéveloppement en questions. Essai de démographie politique (Beauchemin, Kabbanji, Sakho & Shoumaker dir.), Armand Colin/Ined. Recherches. Paris.

- Fondation Abbé Pierre. (2015). L’état du mal logement en Ile-de-France. Un éclairage régional. http://www.fondation-abbe-pierre.fr/sites/default/files/content-files/files/eclairage_regional_2015_-_letat_du_mal-logement_en_ile-de-france.pdf.

- De Genova NP. Migrant “illegality” and deportability in everyday life. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2002;31:419–447. doi: 10.2307/4132887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas, H. (2009). Mobility and human development. Human Development Research Paper. United Nations Development Programme. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdrp_2009_01_rev.pdf.

- de Valk HAG, Windzio M, Wingens M, Aybek C, et al. Immigrant settlement and the life course: An exchange of research perspectives and outlook for the future. In: Wingens, et al., editors. A life-course perspective on migration and integration. New-York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garcin, S. (2011). La mobilité résidentielle des nouveaux migrants. Infos migrations, 21.

- Gosselin, A., Desgrées du Loû, A., & Pannetier, J. (forthcoming). Les migrants subsahariens face à la précarité résidentielle et administrative à l’arrivée en France: l’enquête ANRS Parcours. La population de la France face au VIH/sida (Bergouignan Ed.), Collection Populations Vulnérables.

- Houstoun MF, Kramer RG, Barrett JM. Female predominance of immigration to the United States since 1930: A first look. The International Migration Review. 1984;18(4 Spec No):908–963. doi: 10.1177/019791838401800403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INSEE. (2012a). Étrangers/Immigrés - Séries issues des recensements de la population—RP2011. Cellule “Statistiques et études sur les populations étrangères”.

- INSEE. (2012b). Immigrés et descendants d’immigrés en France. Conditions de vie. Insee Références.

- INSEE. (2012c). Immigrés et descendants d’immigrés en France. Education et maîtrise de la langue. Insee Références

- Jolly, C., Lainé, F., & Breem, Y. (2012). L’emploi et les métiers des immigrés. Document de travail. Centre d’Analyse Stratégique.

- Kleinepier T, de Valk Helga A G, Van Gaalen R. Life paths of migrants: A sequence analysis of Polish migrants’ family life trajectories. European Journal of Population. 2015;31(2):155–179. doi: 10.1007/s10680-015-9345-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larchanché S. Intangible obstacles: Health implications of stigmatization, structural violence, and fear among undocumented immigrants in France. Social Science & Medicine, Part Special Issue: Migration,’illegality’, and health: Mapping embodied vulnerability and debating health-related deservingness. 2012;74(6):858–863. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latcheva R, Herzog-Punzenberger B, et al. Integration trajectories: A mixed method approach. In: Wingens, et al., editors. A life-course perspective on migration and integration. New-York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lelièvre, E., Roubaud, F., Tichit, C., Vivier, G. (2009). Factual data and perceptions: Fuzziness in observation and analysis. In P. Antoine & E. Lelièvre (Eds.), Fuzzy states: Observing, modelling and interpreting complex trajectories in life histories GRAB. Méthodes et Savoirs n°6. Paris: INED/CEPED.

- Mattoo A, Neagu IC, Özden Ç. Brain waste? Educated immigrants in the US labor market. Journal of Development Economics. 2008;87(2):255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazuy M, Barbiery M, d’Albis H. Recent demographic trends in France: The number of marriages continues to decrease. Population. 2014;69(3):313–363. doi: 10.3917/popu.1403.0313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morokvasic M. Birds of passage are also women. The International Migration Review. 1984;18(4):886–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obucina O. Occupational trajectories and occupational cost among Senegalese immigrants in Europe. Demographic Research. 2013;28(19):547–580. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Or Z, Jusot F, Yilmaz E. Inégalités de recours aux soins en Europe, Summary. Revue économique. 2009;60(2):521–543. doi: 10.3917/reco.602.0521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petit P, Duguet E, L’Horty Y, du Parquet L, Sari F. Discrimination à l’embauche: les effets du genre et de l’origine se cumulent-ils systématiquement ? Economie et statistique. 2013;464(1):141–153. doi: 10.3406/estat.2013.10234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piore MJ. Birds of passage: Migrant labor and industrial societies. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Simon P, Beauchemin C, Hamel C. Introduction. In: Beauchemin H, Simon, editors. Trajectoires et Origines. Enquête sur la diversité des populations en France. Paris: Ined; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simón H, Ramos R, Sanromá E. Immigrant occupational mobility: Longitudinal evidence from Spain. European Journal of Population. 2014;30:223–255. doi: 10.1007/s10680-014-9313-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Crowder K, Chavez E. Migration and spatial assimilation among U.S. Latinos: Classical versus segmented trajectories. Demography. 2005;42(3):497–521. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovel K, Bolan M. Residential trajectories using optimal alignment to reveal the structure of residential mobility. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;32(4):598. doi: 10.1177/0049124103262683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu, M. (2006). Les Africains en France. De 1914 à nos jours. Editions du Rocher. Gens d’ici et d’ailleurs. Monaco.

- Toma, S., & Vause, S. (2011). The role of kin and friends in male and female international mobility from Senegal and DR Congo. MAFE Working Paper 13.

- Vickstrom E. Pathways into irregular status among senegalese migrants in Europe. International Migration Review. 2014;48(4):1062–1099. doi: 10.1111/imre.12154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.