Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to compare the diagnostic value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the preoperative evaluation of uterine carcinosarcoma.

Methods

Fifty-four women with pathologically confirmed uterine carcinosarcoma who underwent preoperative FDG PET/CT and MRI from June 2006 to November 2016 were included. Pathologic findings from primary tumor lesions, para-aortic and pelvic lymph node (LN) areas, and peritoneal seeding lesions were compared with the FDG PET/CT and MRI findings. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of the primary tumor and LN was obtained. The tumor-to-liver ratio (TLR) was calculated by dividing the SUVmax of the primary tumor or LN by the mean SUV of the liver.

Results

For detecting primary tumor lesions (n = 54), the sensitivity and accuracy of FDG PET/CT (53/54) and MRI (53/54) were 98.2%. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FDG PET/CT versus MRI were as follows: 63.2% (12/19) versus 26.3% (5/19), 100% (35/35) versus 100% (35/35), and 87.0% versus 74.0%, respectively, for pelvic LN areas (p = 0.016); 85.7% (12/14) versus 42.9% (6/14), 90% (36/40) versus 97.5% (39/40), and 88.9% versus 83.3%, respectively, for para-aortic LN areas (p = 0.004); and 59.4% (19/32) versus 50% (16/32), 100% (22/22) versus 100% (22/22), and 75.9% versus 70.4%, respectively, for peritoneal seeding lesions (p = 0.250). For distant metastasis, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FDG PET/CT were 100 (8/8), 97.8 (45/46), and 98.2%, respectively.

Conclusions

FDG PET/CT showed superior diagnostic accuracy compared to MRI in detecting pelvic and para-aortic LN metastasis in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma. Moreover, FDG PET/CT facilitated the identification of distant metastasis.

Keywords: Uterine carcinosarcoma, 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose, Positron emission tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Uterine carcinosarcoma, also known as malignant mixed Mullerian tumor (MMMT), is a neoplasm composed of epithelial and mesenchymal elements [1, 2]. It is a rare tumor that accounts for less than 5% of all uterine malignancies [3]. Uterine carcinosarcoma behaves aggressively and has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 33–39% [1]. Similar to endometrial cancer, uterine carcinosarcoma is staged using the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) staging system [4]. While most endometrial cancer presents at an early stage, only 40–60% of women with carcinosarcoma present with stage I or II disease [5]. Uterine carcinosarcoma, like endometrial carcinoma, spreads via lymphatic routes, and metastases are usually composed of epithelial elements [6].

Regarding the prognosis of uterine carcinosarcoma, stage, depth of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular invasion, adnexal and uterine serosa involvement, and lymph node metastases are known risk factors [7]. Precise assessment of the tumor extent and lymphatic metastasis in uterine carcinosarcoma is important to optimize treatment planning and patient outcomes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used for the preoperative evaluation of uterine carcinoma and carcinosarcoma [8]. Along with MRI, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) has been reported to enable more exact preoperative planning in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma, especially for the detection of metastatic lymph nodes [9]. However, few studies on FDG PET/CT in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma have been conducted due to the low incidence of the disease [4, 9–12].

The purpose of this study was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of FDG PET/CT and MRI in the preoperative evaluation of uterine carcinosarcoma.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Among 59 patients with pathologically confirmed uterine carcinosarcoma at a single hospital from June 2006 to November 2016, 54 women (median age 60 years, range 30–81 years) who underwent preoperative MRI and FDG PET/CT were included in this retrospective study. Five patients were excluded because MRI was not performed in these patients. This study was approved by the institutional review board, and written informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective design of the study.

PET/CT Protocol

Imaging was performed using either the Biograph TruePoint 40 PET/CT scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) or Discovery 600 PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). All patients fasted for at least 6 h, and blood glucose levels were confirmed to be lower than 140 mg/dL before FDG injection. A dose of 5.5 MBq/kg of FDG was administered to the patients intravenously, and scanning was performed at 60 min after injection. After the initial low-dose CT (Biograph TruePoint 40: 36 mA, 120 kVp; Discovery 600: 30 mA, 130 kVp), standard PET imaging was performed from the neck to the proximal thighs with an acquisition time of 3 min per bed position in the three-dimensional mode. PET images were reconstructed iteratively with CT-based attenuation correction.

MRI Protocol

MRI was performed on a 1.5-Tesla scanner (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands) with a SENSE-body coil. Axial, sagittal, and coronal spin-echo T2-weighted images (repetition time/echo time (TR/TE), 3632–4182/90 ms; slice thickness, 5 mm; number of excitations (NEX), 2; field of view (FOV), 240 mm; matrix, 512 × 256) of the pelvis were acquired. Axial spin-echo T1-weighted images (TR/TE, 678.2/11 ms; slice thickness, 5 mm; NEX, 3; FOV, 240 mm; matrix, 256 × 256) were acquired. Gradient-echo precontrast fat-suppressed sagittal T1-weighted images (THRIVE: TR/TE, 3.1/1.9 ms; slice thickness, 4 mm; NEX, 1; echo-train length, 48; FOV, 370 mm; matrix, 336 × 307) were also acquired. After the injection of gadolinium chelate (Dotarem; Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) intravenously, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted axial images (THRIVE: TR/TE, 4.5/2.2 ms; slice thickness, 4 mm; NEX, 1; echo-train length, 60; FOV, 400 mm; matrix, 320 × 224) were acquired.

Surgical Staging

All patients underwent surgical staging, comprising hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and/or para-aortic LN dissection, peritoneal washing cytology, omentectomy, and surgical excision or biopsy for suspected peritoneal seeding lesions. Bilateral pelvic LN dissection consisted of removing LNs from the internal iliac, the external iliac and common iliac vessels, and the obturator fossa. Para-aortic LNs were dissected from pre-caval, aortocaval, and lower right and left para-aortic LNs to the level of the renal hilum. Peritoneal seeding metastasis was diagnosed upon dissection of suspicious sites in the abdominal pelvic cavity and peritoneal washing cytology. Distant metastasis was confirmed upon biopsy of suspicious sites and other imaging findings or progression on follow-up images.

Image Analysis

All PET/CT images were registered using a fusion module in the imaging software MIM (MIM-6.5; MIM software Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) on a dedicated workstation and were reviewed and analyzed by two nuclear medicine physicians. Sizes of primary tumors were determined on images. Findings were considered positive for primary lesion or LN metastasis on FDG PET/CT when focally higher FDG uptake than that in the surrounding tissue was seen in the locations corresponding to the lesions on the CT images. The volume of interest (VOI) was drawn on the primary tumor or LN based on the contour observed on CT, and the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was recorded. In addition, the mean SUV (SUVmean) of the liver was obtained by drawing VOI with a 1-cm-sized diameter on the normal liver parenchyma of the right hepatic lobe. The tumor-to-liver ratio (TLR) was calculated by dividing the SUVmax of the primary tumor or LN by the SUVmean of the liver. The criterion for LN metastasis on MRI was a short diameter of the pelvic or para-aortic LN of more than 1 cm [13]. Pathologic findings from primary tumor lesions, para-aortic and pelvic LN areas, and peritoneal seeding were compared with the preoperative MRI and FDG PET/CT findings on a patient- basis.

Statistics

The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were evaluated. Diagnostic performances of PET/CT and MRI were compared using R Core Team (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/) with package DTComPair for R (R package ver. 1.0.3). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined by a p value < 0.05 for all statistical analyses. ROC curves were analyzed to evaluate the ability of the SUVmax and TLR to identify para-aortic LN metastasis.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 54 patients (median age: 60 years, range 30–81 years) with uterine carcinosarcoma, 46 (85.2%) patients were postmenopausal. The median time interval between FDG PET/CT and MRI was 1 day (range 0–36 days). The median times from FDG PET/CT and MRI to the staging operation were 4 (range 0–34 days) and 5 days (range 0–43 days), respectively. All patients underwent hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic LN dissection. Para-aortic LN dissection was performed in 46 patients, peritoneal washing cytology in 48 patients, omentectomy in 37 patients, and surgical excision or biopsy for suspected peritoneal seeding lesions in 21 patients. In eight cases of distant metastasis, three patients were confirmed upon biopsy of suspicious sites, and five patients were diagnosed from imaging findings or progression on follow-up images.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients, n | 54 | |

| Age at diagnosis, year, median (range) | 60 (30–81) | |

| Postmenopausal, n | 46 (85.2%) | |

| FIGO stage, n | I | 13 (24.1%) |

| II | 2 (3.7%) | |

| III | 27 (50.0%) | |

| IV | 12 (22.2%) | |

| Tumor size, cm, median (range) | 6.0 (0.9–25.4) | |

| LN metastasis, n | 22 (40.7%) | |

| Pelvic LN metastasis, n | 19 (35.2%) | |

| Para-aortic LN metastasis, n | 14 (25.9%) | |

| Distant metastasis, n | 8 (14.8%) | |

Evaluation of FDG PET/CT and MRI in Detecting Primary Lesions

In the detection of primary tumor lesions, 53 of 54 patients (98.2%) had true positive findings. One patient had false negative results showing no delineable lesion with FDG uptake in the uterus on both FDG PET/CT and MRI. That patient underwent biopsy before the imaging studies: after staging surgery, residual carcinosarcoma presenting as an ill-defined shallow ulcerative lesion in the endometrial mucosa, measuring 1 × 0.5 cm was found on pathology. The median SUVmax of the primary tumor was 15.34 (range 3.17–40.73), and the median TLR was 6.38 (range 1.22–15.22).

Evaluation of FDG PET/CT and MRI in Detecting Pelvic and Para-aortic LN Metastases

For pelvic and para-aortic LN areas, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV of FDG PET/CT versus MRI are presented in Table 2. Seven patients had false negative results on FDG PET/CT. There was a significant difference in sensitivity between FDG PET/CT and MRI (p = 0.008). The median SUVmax of 12 positive findings for pelvic LN metastases was 6.38 (range 1.88–18.79), and the median TLR was 3.59 (range 0.89–6.5). There were seven cases with a positive finding on FDG PET/CT, a negative finding on MRI for pelvic LN metastasis, and positive pathologic results. In these cases, while the median size of metastatic LNs was 5.80 mm (range 4.00–8.90 mm), the median SUVmax of metastatic LNs was 4.97 (range 2.61–18.79).

Table 2.

Comparison of the diagnostic values between FDG PET/CT and MRI for lymph node metastasis

| Imaging modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For pelvic LN | p = 0.008 | NA | |||

| FDG PET/CT | 63.2 (12/19) | 100 (35/35) | 87.0 (47/54) | 100 (12/12) | 83.3 (35/42) |

| MRI | 26.3 (5/19) | 100 (35/35) | 74.1 (40/54) | 100 (5/5) | 71.4 (35/49) |

| For para-aortic LN | p = 0.014 | p = 0.083 | |||

| FDG PET/CT | 85.7 (12/14) | 90 (36/40) | 88.9 (48/54) | 75 (12/16) | 94.7 (36/38) |

| MRI | 42.9 (6/14) | 97.5 (39/40) | 83.3 (45/54) | 85.7 (6/7) | 83.0 (39/47) |

NA, not available

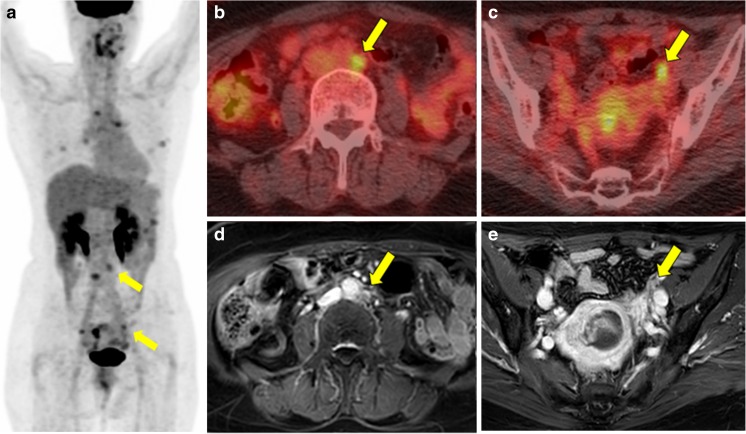

Two patients had false negative results and 4 had false positive results on FDG PET/CT. There was a significant difference in sensitivity between FDG PET/CT and MRI (p = 0.014). The median SUVmax of 12 positive findings of para-aortic LN was 8.42 (range: 2.10–17.58), and the median TLR was 4.40 (range 0.83–6.89). In six cases for para-aortic LN metastasis with positive findings on FDG PET/CT and negative findings on MRI, the pathologic results were positive. In these cases, while the median size of metastatic LNs was 7.05 mm (range 3.70–8.40 mm), the median SUVmax of metastatic LNs was 8.18 (range 2.10–15.97). Figure 1 reflects a representative case of a patient with matched positive findings, whereas Fig. 2 shows a discrepant case between FDG PET/CT and MRI for detecting pelvic and para-aortic LN metastasis.

Fig. 1.

Case of a 55-year-old woman with uterine carcinosarcoma who underwent FDG PET/CT and MRI. a MIP image shows focal intense FDG uptake in the endometrium (SUVmax: 10.89, TLR: 6.94), para-aortic LNs (SUVmax: 6.91, TLR: 4.40), right external iliac (SUVmax: 6.29 and TLR: 4.01), and perigastric LNs, and Rt. subhepatic nodule. b Fusion images of FDG PET/CT for para-aortic LN and c pelvic LN, d enhanced MRI of heterogeneous endometrial mass with large-sized para-aortic (14 mm), and e right external iliac LNs (11 mm) which suggest uterine malignancy with pelvic and para-aortic LN metastasis. After surgery, uterine carcinosarcoma with para-aortic, right external iliac LN metastasis, and peritoneal seeding metastasis was confirmed. Yellow arrows indicate para-aortic and pelvic LN metastasis

Fig. 2.

Case of a 58-year-old woman with uterine carcinosarcoma who underwent FDG PET/CT and MRI. a MIP image shows focal intense FDG uptake in the endometrium (SUVmax: 10.90, TLR: 3.81), para-aortic LNs (SUVmax: 4.86, TLR: 1.70), and both external iliac LNs (SUVmax: 4.97 and TLR: 1.74 for Rt; SUVmax: 4.12 and TLR: 1.44 for Lt.). b Fusion images of FDG PET/CT for para-aortic LN and c pelvic LN suggest LN metastasis. d Enhanced MRI: heterogeneous endometrial mass with small-sized (less than 1 cm) para-aortic and e left external iliac LNs suggest uterine malignancy without LN metastasis. After surgery, uterine carcinosarcoma with para-aortic and both external iliac LN metastasis was confirmed. Yellow arrows indicate para-aortic and pelvic LN metastasis

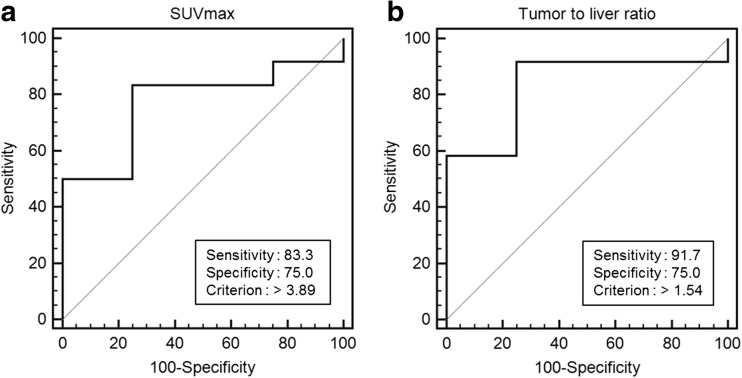

ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the cutoff value of the SUVmax for detecting para-aortic LN metastasis (Fig. 3). With a cutoff value of 3.89, a sensitivity of 83.3% and specificity of 75.0% were obtained (area under the curve (AUC) 0.771, p = 0.041). Furthermore, the optimal cutoff value of the TLR for detecting para-aortic LN metastasis was 1.54, with a sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 75.0% (AUC 0.833, p = 0.005).

Fig. 3.

a ROC curve analysis to determine the optimal cutoff value of SUVmax for detecting para-aortic LN metastasis. With cutoff value of 3.89, a sensitivity of 83.3% and specificity of 75.0% were obtained (AUC: 0.771, p = 0.041). b ROC curve analysis to determine the optimal cutoff value of the TLR for detecting para-aortic LN metastasis. With a cutoff value of 1.54, a sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 75.0% were obtained (AUC: 0.833, p = 0.005)

Evaluation of FDG PET/CT and MRI in Detecting Peritoneal Seeding Metastases

For peritoneal seeding lesions, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV of FDG PET/CT versus MRI are provided in Table 3. Three more peritoneal seeding metastases were detected on FDG PET/CT than on MRI (p = 0.083 for difference in sensitivity). Gross peritoneal seeding lesions were seen in four patients, and peritoneal washing cytology was positive in 28 patients.

Table 3.

Comparison of the diagnostic values between FDG PET/CT and MRI for peritoneal seeding and distant metastasis

| Imaging modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For peritoneal seeding | p = 0.083 | NA | |||

| FDG PET/CT | 59.4 (19/32) | 100 (22/22) | 75.9 (41/54) | 100 (19/19) | 62.9 (22/35) |

| MRI | 50 (16/32) | 100 (22/22) | 70.4 (38/54) | 100 (16/16) | 57.9 (22/38) |

| For distant metastasis | |||||

| FDG PET/CT | 100 (8/8) | 97.8 (45/46) | 98.2 (53/54) | 88.9 (8/9) | 100 (45/45) |

NA, not available

Evaluation of FDG PET/CT in Detecting Distant Metastases

FDG PET/CT detected distant metastases in eight patients (14.8%). The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV of FDG PET/CT are listed in Table 3. Lesions of the lung (n = 4), liver (n = 3), left supraclavicular LN (n = 3), hilar and mediastinal LN metastasis (n = 2), and bone (n = 2) were detected. One patient had a false positive result showing increased FDG uptake in the hilar and mediastinal LNs. These were deemed reactive LNs in light of the absence of interval change on FDG PET/CT after 5 months. Figure 4 shows a representative case of a patient with lung and liver metastasis.

Fig. 4.

Representative case of a 53-year-old woman who underwent FDG PET/CT and MRI. a A MIP image, b fusion images of FDG PET/CT of a lung nodule, c primary uterine mass, d hepatic metastasis, and e enhanced MRI of the primary uterine mass. Intense FDG uptake in the uterine mass (SUVmax: 16.17, TLR: 12.63), multiple retroperitoneal LNs, small bowel, multiple hepatic lesions, and lung nodules suggested uterine malignancy with retroperitoneal LNs, small bowel, liver, and lung metastasis

Discussion

FIGO staging has been identified as the most important prognostic factor for patients with uterine carcinosarcoma [14]. About 60% of patients with carcinosarcoma demonstrate extrauterine extension at diagnosis and 10% have distant metastases, including those with apparent early-stage disease [15]. Preoperative staging through imaging is useful for determining the extent of surgery. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for uterine neoplasm recommend that MRI and FDG PET/CT be used to evaluate disease extent and metastatic disease [16]. To our knowledge, only one previous study has investigated the validity of MRI and FDG PET/CT in the preoperative evaluation of uterine carcinoma, in which it was suggested that FDG PET/CT may be useful to detect LN metastasis and extrauterine metastases as well as primary lesions [9].

In this study, both FDG PET/CT and MRI showed a high sensitivity (98.2%) for detecting primary tumors, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study (sensitivity 98.1%) [9]. One false negative result may have been caused by a small residual volume of the tumor after a biopsy procedure. There were no negative pathologic results for primary lesions in this study, and the SUVmax of all primary tumors was higher than the liver uptake.

For detecting pelvic LN metastasis, the sensitivity of FDG PET/CT was 63.2%, which was higher than that of MRI (26.3%). In addition, for detecting para-aortic LN metastasis, the sensitivity of FDG PET/CT was 85.7%, which was also higher than that of MRI (42.9%). These results are consistent with a previous study in which FDG PET/CT showed a higher sensitivity than MRI for detecting pelvic LN metastasis (61.1% versus 50%) and para-aortic LN metastasis (77.8% versus 51.9%) [9]. In the detection of LN metastases, MRI is limited by the fact that the LN size is a major factor for determining metastasis [17]. In contrast, FDG PET/CT is capable of capturing metabolic information, which has been reported to be useful for detecting metastatic LNs in cervical and endometrial cancer [18, 19].

In the detection of pelvic LN metastasis, there was no incidence of false positivity, and the specificity was 100% for both FDG PET/CT and MRI. For detecting para-aortic LN metastasis, the specificity of FDG PET/CT was 90%, which was lower than that of MRI (97.5%). Four patients had false positive results. These findings are similar to those of a previous study in which FDG PET/CT showed a lower specificity (90.2% vs. 100%) than MRI for para-aortic metastasis [9]. According to the NCCN guidelines, the standard treatment for uterine carcinosarcoma is hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and para-aortic lymph node sampling with peritoneal washings, although the additional benefit of lymphadenectomy remains controversial [14, 16, 20, 21]. Owing to the high NPV of FDG PET/CT for pelvic (83.3%) and para-aortic (94.7%) LN metastasis, we might opt to reduce the performance of unnecessary lymphadenectomy and postoperative complications, such as lymphocele for selected patients in poor condition who could be considered for adjuvant treatment.

FDG PET/CT was useful for detecting distant metastasis. For patients with advanced unresectable uterine carcinosarcoma, aggressive treatment did not seem to change the poor outcome of the disease. Palliative therapy should be considered for patients with clinically advanced stage disease in order to avoid the needless suffering of patients and improve cost-effectiveness [10]. Distant metastatic sites included the lung (n = 4), liver (n = 3), left supraclavicular LN (n = 3), hilar and mediastinal LNs (n = 2), and bone (n = 2).

There were some limitations to this study. First, due to the nature of this retrospective study, bias in patient selection might have been introduced, and we could not control scheduling of the images, biopsy, and surgery. Further prospective studies are needed to address this. Second, this study included a small number of patients. However, because the disorder is so rare, this was the second largest study on uterine carcinosarcoma. Third, this study was patient-based, as opposed to lesion-based, due to the difficulty of matching the lesions seen on images with pathologically confirmed sites.

Conclusion

The diagnostic accuracy of FDG PET/CT was superior to that of MRI for detecting pelvic and para-aortic LN metastasis in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma. In addition, FDG PET/CT was particularly helpful in identifying distant metastasis.

Conflict of Interest

Won Jun Kang declares that this research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI17C1491) and the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (No. 2018004651). Soyoung Kim, Young Tae Kim, Sunghoon Kim, Sang Wun Kim, and Jung-Yun Lee declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The institutional review board of our institute approved this retrospective study, and the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived.

References

- 1.Cantrell LA, Blank SV, Duska LR. Uterine carcinosarcoma: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artioli G, Wabersich J, Ludwig K, Gardiman MP, Borgato L, Garbin F. Rare uterine cancer: carcinosarcomas. Review from histology to treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Seshan VE, Schiff PB, Burke WM, Cohen CJ, et al. Uterine carcinosarcomas and grade 3 endometrioid cancers: evidence for distinct tumor behavior. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:64–70. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318176157c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menczer J. Review of recommended treatment of uterine carcinosarcoma. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2015;16:53. doi: 10.1007/s11864-015-0370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gokce ZK, Turan T, Karalok A, Tasci T, Ureyen I, Ozkaya E, et al. Clinical outcomes of uterine carcinosarcoma: results of 94 patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:279–287. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang YT, Chang CB, Yeh CJ, Lin G, Huang HJ, Wang CC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 3.0 T diffusion-weighted MRI for patients with uterine carcinosarcoma: assessment of tumor extent and lymphatic metastasis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lee HJ, Park JY, Lee JJ, Kim MH, Kim DY, Suh DS, et al. Comparison of MRI and 18F-FDG PET/CT in the preoperative evaluation of uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho KC, Lai CH, Wu TI, Ng KK, Yen TC, Lin G, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in uterine carcinosarcoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:484–492. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0533-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen F, Yu C, You X, Mi B, Wan W. Carcinosarcoma of the uterine corpus on 18F-FDG PET/CT in a postmenopausal woman with elevated AFP. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:803–805. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182a77b90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HJ, Lee JJ, Park JY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, et al. Prognostic value of metabolic parameters determined by preoperative (1)(8)F-FDG PET/CT in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;e43:28. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin G, Ho KC, Wang JJ, Ng KK, Wai YY, Chen YT, et al. Detection of lymph node metastasis in cervical and uterine cancers by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at 3 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:128–135. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemani D, Mitra N, Guo M, Lin L. Assessing the effects of lymphadenectomy and radiation therapy in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma: a SEER analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arend R, Doneza JA, Wright JD. Uterine carcinosarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23:531–536. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328349a45b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, Bradley K, Campos SM, Cho KR, et al. Uterine neoplasms. Version 1.2018. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2018;16:170–199. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Cho A, Yun M, Kim YT, Kang WJ. Comparison of FDG PET/CT and MRI in lymph node staging of endometrial cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2016;30:104–113. doi: 10.1007/s12149-015-1037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JY, Kim EN, Kim DY, Suh DS, Kim JH, Kim YM, et al. Comparison of the validity of magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the preoperative evaluation of patients with uterine corpus cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhardt MJ, Ehritt-Braun C, Vogelgesang D, Ihling C, Hogerle S, Mix M, et al. Metastatic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer: detection with MR imaging and FDG PET. Radiology. 2001;218:776–782. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr19776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sagae S, Yamashita K, Ishioka S, Nishioka Y, Terasawa K, Mori M, et al. Preoperative diagnosis and treatment results in 106 patients with uterine sarcoma in Hokkaido, Japan. Oncology. 2004;67:33–39. doi: 10.1159/000080283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temkin SM, Hellmann M, Lee YC, Abulafia O. Early-stage carcinosarcoma of the uterus: the significance of lymph node count. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:215–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]