Abstract

The model of centralized stroke care in the Czech Republic was created in 2010–2012 by Ministry of Health (MH) in cooperation with professional organization—Cerebrovascular Section of the Czech Neurological Society (CSCNS). It defines priorities of stroke care, stroke centers, triage of suspected stroke patients, stroke care quality indicators, their monitoring, and reporting. Thirteen complex cerebrovascular centers (CCC) provide sophisticated stroke care, including intravenous thrombolysis (IVT), mechanical thrombectomy (MTE), as well as other endovascular (stenting, coiling) and neurosurgical procedures. Thirty-two stroke centers (SC) provide stroke care except endovascular procedures and neurosurgery. The triage is managed by emergency medical service (EMS). The most important quality indicators of stroke care are number of hospitalized stroke patients, number of IVT, number of MTE, stenting and coiling, number of neurosurgical procedures, and percentage of deaths within 30 days. Indicators provided into the register of stroke care quality (RES-Q) managed by CSCNS are time from stroke onset to hospital admission, door-to-needle time, door-to-groin time, type of ischemic stroke, and others. Data from RES-Q are shared to all centers. Within the last 5 years, the Czech Republic becomes one of the leading countries in acute stroke care. The model of centralized stroke care is highly beneficial and effective. The quality indicators serve as tool of control of stroke centers activities. The sharing of quality indicators is useful tool for mutual competition and feedback control in each center. This comprehensive system ensures high standard of stroke care. This system respects the substantial principles of personalized medicine—individualized treatment of acute stroke and other comorbidities at the acute disease stage; optimal prevention, diagnosis and treatment of possible complications; prediction of further treatment and outcome; individualized secondary prevention, exactly according to the stroke etiology. The described model of stroke care optimally meets criteria of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine (PPPM), and could be used in other countries as well with the aim of improving stroke care quality in general.

Keywords: Stroke, Stroke care organization, Centralized stroke care, Stroke centers, Intravenous thrombolysis, Mechanical thrombectomy, Quality indicators, Personalized medicine, Personalized stroke treatment, Personalized stroke prevention, Centralized stroke care

Introduction

Cerebrovascular events (strokes) belong to the most important civilization diseases with a high impact on the health and quality of life. They are among the five most common causes of death and disability. The age-standardized incidence of stroke in Europe ranges from 95 to 290/100,000 per year, with 1-month case-fatality rates ranging from 13 to 35%. Approximately 1.1 million inhabitants of Europe suffer a stroke each year at the beginning of twenty-first century [1]. Higher rates of stroke were observed in eastern and lower rates in southern European countries [2]. In the EU, the total cost of stroke in 2015 was calculated as €45 billion. Stroke has negative influence on socioeconomic status of population in low-income, middle-income, and also in high-income countries of the world [3].

In the Czech Republic (CR), stroke is the third most frequent cause of death and the most frequent cause of adult disability. The treatment and prevention of stroke together with the complex care for patients and their families are the important tasks of health care and the health system in general [4–6]. Originally, unfavorable situation in the acute treatment of this disease changed significantly after the introduction of recanalization therapy of ischemic stroke—intravenous thrombolysis (IVT)—by recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-TPA) given within the first 3 h of symptoms onset [7]. Significant results of ECASS study contributed to the extension of therapeutic window up to 4.5 h [8]. An important additional pillar for the treatment strategy of ischemic stroke caused by large vessel occlusion (LVO) (ICA, VA, BA, MCA sections M1–2, ACA sections A1–2) represent the results of McClean et al. and other studies [9–12], demonstrating the positive effect of mechanical thrombectomy (MTE) in an even longer time window since symptoms onset (8 h, in exceptional cases up to 24 h).

Strokes are heterogeneous diseases with different etiology and different treatment options. The implementation of PPPM strategies in individualized therapeutic interventions and optimal secondary prevention is a cardinal task of medical care of stroke patients worldwide. Concentration of acute stroke care to stroke centers with multidisciplinary cooperation dramatically improves morbidity/mortality [13, 14]. Interdisciplinary teams and specialized workplaces of stroke centers are able to provide individualized care for all stroke etiologies, acute stroke treatment, comorbidities treatment, prevention and treatment of complications, and secondary prevention.

There exist the recommendations for the medical care of patients with ischemic as well as hemorrhagic strokes elaborated by international professional societies (European Stroke Organization (ESO) guidelines or American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines), and usually also by the professional societies in an individual country possibly modifying.

The presented article describes the model of centralized stroke care in the CR that was created and optimized during the last 5 years. Authors discuss the importance of this model and its potential contribution to improving and individualizing stroke care in CR according to the personalized medicine philosophy. The registration, submission, and sharing of indicators of stroke care quality (“quality indicators”) among stroke centers are also discussed.

The organization of stroke care in the Czech Republic

The clinical care of patients with acute stroke has been traditionally provided at the beds of internal or neurological departments in state and private hospitals in the CR. However, only a few hospitals provided the recanalization treatment. On the basis of cooperation between the Ministry of Health of the CR (MH) and the professional organization (Cerebrovascular Section of the Czech Neurological Society of Jan Evangelista Purkyne (CSCNS)), the centralized health care system for patients with stroke was created in 2010–2012. The legal standards (MH bulletins) defined the following components [15–18]:

Health care for patients with cerebrovascular diseases in CR and the system of three-step stroke health care and stroke centers

The principles of triage of patients with suspected stroke

Monitoring system and mandatory reporting of stroke care quality indicators in stroke centers

The health care for patients with cerebrovascular diseases in the Czech Republic

The preparations for establishing of stroke centers were in progress during the years 2010–2011. The MH commission staff together with the representatives of the CSCNS made visits across all health care facilities that were candidates for stroke centers. It was a checkup of expertise, staffing, room capacities, and medical equipment necessary for the diagnostics and treatment of strokes in accordance with the required criteria. Missing items were complemented from the state budget together with EU funding. The entire network of stroke centers has begun to work effectively on January 1, 2013. The network consists of system of three-step stroke centers:

Complex cerebrovascular center (CCC)

Health care facility providing continuous specialized comprehensive care in the following specializations—neurology, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, radiology and imaging methods, interventional neuroradiology, rehabilitation and physical medicine, internal medicine, and cardiology. Stroke care in CCC is coordinated by the neurology department with the stroke unit or intensive care unit (ICU), or within a multidisciplinary ICU with dedicated beds and staff for cerebrovascular care. CCC provides comprehensive diagnostic, therapeutic, and early rehabilitation care for patients with the whole spectrum of cerebrovascular diseases. The following procedures are mandatory: intravenous thrombolysis and intraarterial thrombolysis, mechanical thrombectomy, neurosurgical and endovascular procedures for aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations and stenoses of extracranial arteries, decompression craniectomy, operations for intracerebral hematomas, and other neurosurgical procedures. Other activities related to rehabilitation, nursing, or follow-up care are also an integral part of CCC.

-

2)

Stroke center (SC)

Stroke center provides similar range of medical care as CCC with the exception of neurosurgery and interventional neuroradiology.

-

3)

The other facilities providing cerebrovascular care

The basic level of cerebrovascular care is provided by acute and subsequent inpatient and outpatient health care facilities specialized in neurology, internal medicine, geriatrics, rehabilitation, and physical medicine. This level of stroke care is mainly intended for the comprehensive rehabilitation and long-term care of patients previously treated in CCC and SC.

The principles of triage of patients with suspected stroke

Triage involves the identification of patients with stroke and their routing into CCC, SC, or facility providing other cerebrovascular care. Regarding triage stroke is defined as the brain infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and transient ischemic attack (TIA). Triage is performed by the emergency medical service (EMS). The triage-positive subject is quickly identified on the basis of patient’s clinical status (present or subside suspected symptoms of stroke), time aspect (onset of symptoms within last 24 h), and presence of additional diseases (other serious diseases and concurrently administrated treatment).

Routing of the triage-positive patient from the site of stroke occurrence to the medical facility providing acute stroke care is always preceded by a phone consultation of EMS staff with the stroke center physician. The patient is routed directly into CCC or SC if the time window from stroke onset is less than 8 h. When suspected for SAH, arterial dissection, cerebral venous thrombosis, or if IVT administration is contraindicated, the patient is referred to CCC. If the time window from occurrence is demonstrable longer than 8 h and there is no suspicion of SAH, arterial dissection, cerebral venous thrombosis, or TIA, the patient may be routed after consultation to a hospital providing other cerebrovascular care.

Following mandatory data must be transferred by EMS to the physician of the receiving health care facility:

The exact time of symptoms onset (the time when the patient was last healthy—he/she himself or the witnesses stated that he/she was really healthy) or the time when the patient was found to be witnesses

Telephone contact for a person or persons capable of supplementing the duration of the symptoms, anamnestic patient’s data, and circumstances of stroke (family members, evidence of stroke)

Clinical condition (consciousness assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale, indicatively severity of stroke—mobility and speech failure assessed by FAST protocol [Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties and Time to call emergency services]) [19]

Other serious illnesses

Permanent medication and its dosage

Indicators of stroke care quality

The Ministry of Health has established indicators of stroke care quality, “quality indicators,” which all stroke centers are obliged to monitor and supply to MH at regular intervals twice a year:

Number of hospitalized patients with stroke

Number of ischemic strokes

Number of IVTs

Number of IVTs performed during the first 60 min of hospital stay

Number of interventional neuroradiology procedures (MTE, stenting, coiling)

Number of hemorrhagic strokes

Number of neurosurgical procedures

Percentage of patients admitted to stroke unit or ICU

Percentage of patients treated at rehabilitation department

Percentage of deaths during the first 30 days after stroke onset

The MH therefore has anonymized data on stroke care provided from 2013 from all stroke centers. Accordingly, quality indicators are a control instrument of the MH for monitoring the quantity and quality of stroke care in all centers of the CR. MH publishes global data, but the particular data from an individual center are not published.

Another subject that is involved in the organization of stroke care in CR is the professional organization—CSCNS. In 2016, CSCNS created its own registry of stroke care quality (RES-Q) [20]. The RES-Q is filled by all stroke centers. Part of the indicators is the same as the MH quality indicators (number of hospitalized patients with stroke, number of IVTs, number of MTEs, and others). Above that, there are additional indicators that are monitored:

Time from first signs or symptoms of stroke to admission into the hospital

Door-to-needle time (time from the patient’s arrival into the hospital to IVT initiation)

Door-to-groin time (time from the patient’s arrival into the hospital to MTE initiation)

Type of ischemic stroke

Percentage of patients with ischemic stroke that are examined by Holter ECG

Percentage of patients with stroke that are screened for dysphagia

This registry includes all patients with stroke as the main diagnosis (for which patients were admitted to stroke center), as well as patients who experience stroke during hospitalization for another health condition. All data are anonymized. Data collection is voluntary and data from the RES-Q registry are shared among stroke centers as electronic reports. Therefore, each center has an overview of stroke care in other stroke centers in the CR.

Data for the MH registry and for RES-Q present the management and the clinical outcome of patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (information on discharge from hospital, acute rehabilitation care, transfer to the social care facility, patient’s death) and do not incorporate the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) assessment.

The occurrence of infection complications is the important issue during the stroke care. The prediction for risk of infection complications development in an individual stroke patient can be good example of the application of personalized medicine in cerebrovascular diseases [21]. The incidence of infectious complications during the stroke treatment is not part of MH nor RES-Q registries. However, infectious complications are required to be assessed as a part of hospital nosocomial infections monitoring done by MH.

An important part of the centralized stroke care is also rehabilitation (during the acute disease phase as well as long-term rehabilitation). Each of the stroke centers must dispose with 20 beds for acute rehabilitation care. Percentage of patients treated at rehabilitation department of stroke centers is one of the indicators in the MH registry. However, rehabilitation is also provided on an outpatient basis and in other facilities (specialized rehabilitation institutes, spa facilities, etc.). However, these data are not incorporated into the registers.

Holter ECG is an important tool for detecting cardioembolic strokes and for optimal secondary prevention. It is recommended for all ischemic strokes where the etiology is not clearly identified. One of the indicators of the RES-Q database is the percentage of the Holter ECG indication for those types of ischemic stroke.

Another example is an international SITS registry (Safe Implementation of Treatment in Stroke), which is managed by ESO [22]. It is desirable to include anonymized stroke patients data from the European countries. However, there is no guarantee that all the data on all strokes from all centers and from all countries are inserted into the register.

Moreover, data on strokes (as the main disease according to the International classification of diseases—I60–I64) are obligatory monitored and reported across all health care facilities in CR (hospitalizations and deaths). The deaths for these diagnoses outside health care facilities are also monitored. These data (managed by the Institute of health information and statistics of the CR) are publicly available as basic data on the stroke incidence and mortality [23]. Mortality of strokes is evaluated by two indicators: 30-day mortality (indicator for the MH) and total stroke mortality as the main diagnosis (indicator for the Institute of health information and statistics of the CR). The international comparison of stroke mortality in European countries is provided by the Eurostat database [24]. Monitoring of stroke morbidity and long-term disability on an international scale is considered very limited and is not used.

The current stroke database in the Czech Republic is targeted as a registry of quantity and quality of stroke care. Indicators for MH do not include information about stroke etiology. However, the RES-Q database already includes a TOAST classification of ischemic strokes with a group of rare causes (I63.8—vasculitis, arterial dissection, cerebral venous thrombosis, etc.) [25, 26].

The progression of stroke care and its indicators in the Czech Republic

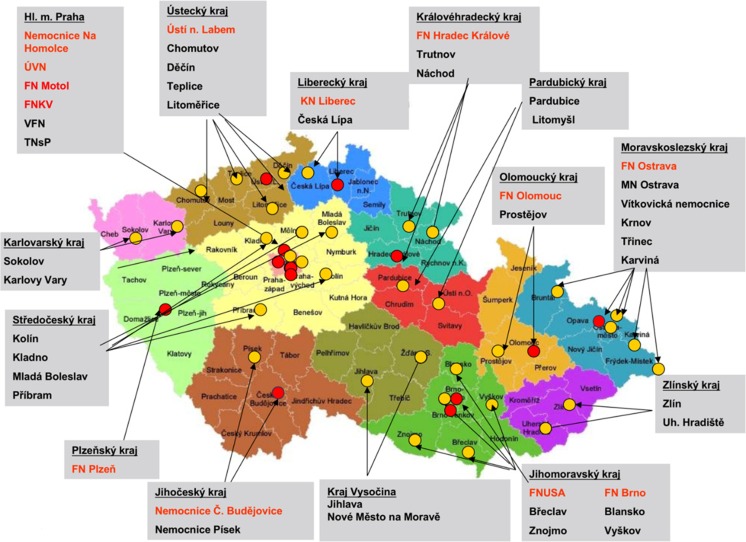

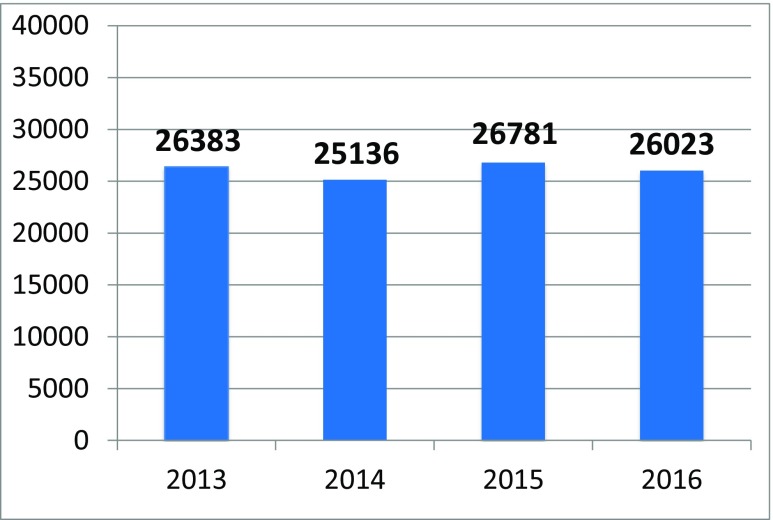

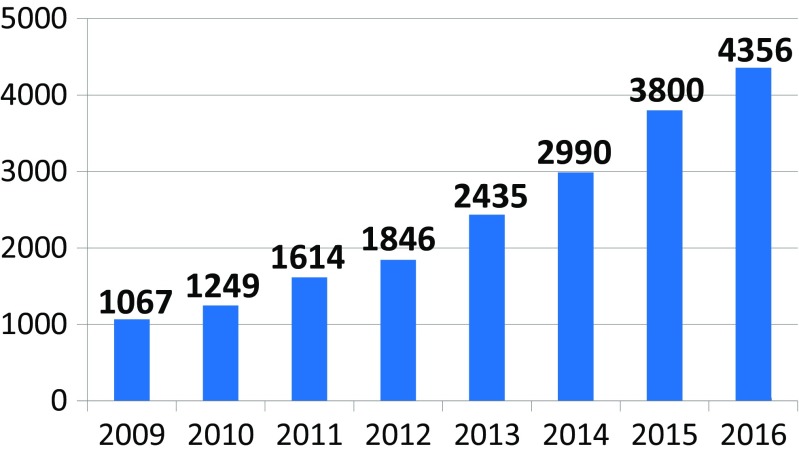

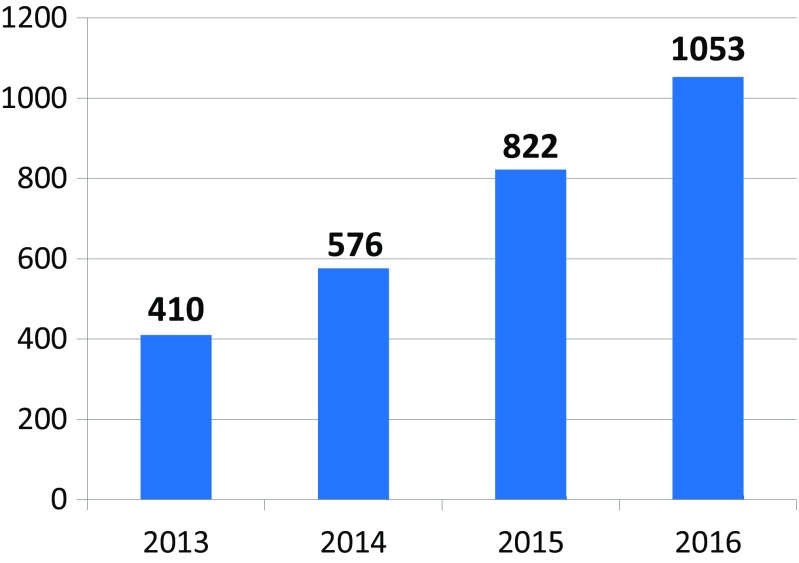

The network of founded stroke centers is shown in Fig. 1. During the years 2013–2016, the similar amount of patients with stroke per year was hospitalized in CR (Fig. 2). Even thought IVT was used in the treatment of ischemic strokes in previous years as well, number of procedures was increased substantially after the development of a network of stroke centers, and further increase in IVT administration was observed after the introduction of stroke patients triage (Fig. 3). A similar increase was observed for MTE (Fig. 4). The percentage of ischemic stroke patients treated with IVT is also increasing (Fig. 5). The number of IVT administration per 1,000,000 inhabitants in the year 2016 was 360, and that was the third highest number in Europe (behind Germany and Estonia) [27]. The number of MTE per 1,000,000 inhabitants in the year 2016 was 100, and 6.2% of acute ischemic strokes were treated by MTE. Recanalization therapy (IVT, MTE, and concurrent IVT + MTE) was administrated in 27.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke in 2016. At the same time, door-to-needle time and door-to-groin time are reduced year-on-year (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 1.

The map of all stroke centers across the Czech Republic. Complex stroke center—IVT, interventional neuroradiology, neurosurgery, cardiology (red). Stroke center—stroke care, IVT, 250–300,000 IH (yellow)

Fig. 2.

A number of stroke patients hospitalized in stroke centers across the Czech Republic during the years 2013–2016

Fig. 3.

A number of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) administrated to stroke patients in the Czech Republic during the years 2009–2016

Fig. 4.

A number of mechanical thrombectomy (MTE) administrated to stroke patients in the Czech Republic during the years 2013–2016

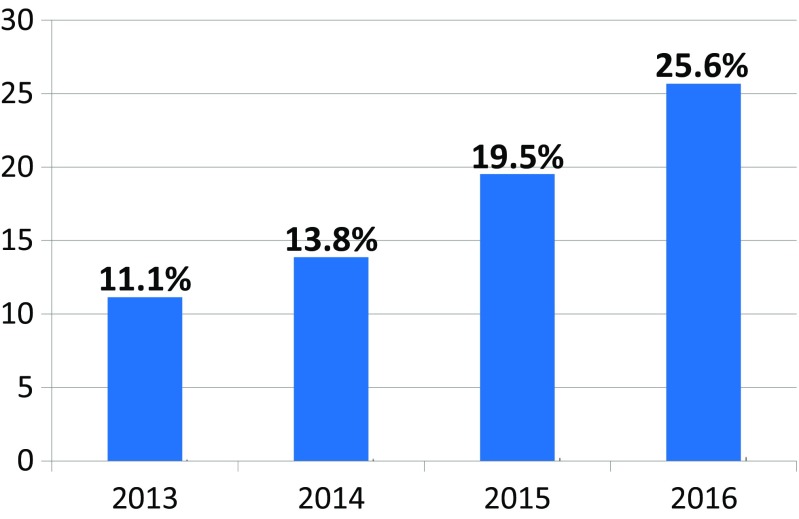

Fig. 5.

The percentage of ischemic stroke patients treated by intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) in the Czech Republic during the years 2013–2016

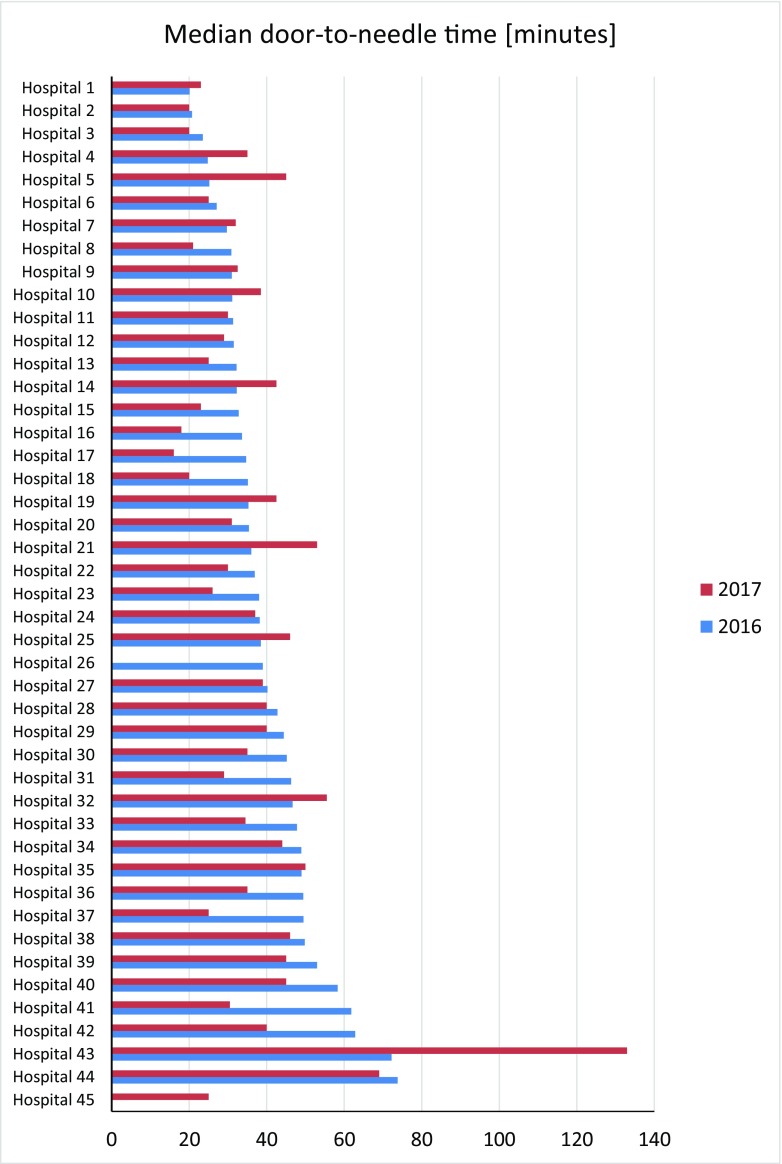

Fig. 6.

Door-to-needle time within stroke centers in the Czech Republic during the years 2016 and 2017—shared indicators, hospital names are anonymized

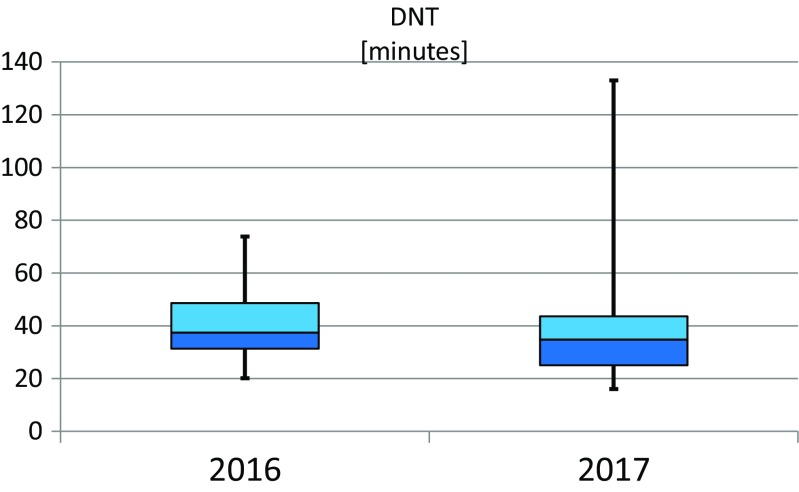

Fig. 7.

Box plot of door-to-needle time (DNT) for all stroke centers in the Czech Republic during the years 2016 and 2017—shared indicators

Discussion

The stroke care can be conducted according to the recommendations of international organizations (e.g., ESO) or the professional organizations from an individual country. Another option is the organization of stroke care defined by rules that are set up as legal norms created by state authorities in cooperation with experts of a professional organization. This way enables to form a national concept of centralized stroke care with its stratification into particular health care facilities. Acute stroke care can be centralized into several large fully equipped centers (such as CCC). Another option is to create a network of more stroke centers in a particular region, with one fully equipped CCC comprising a quality multidisciplinary team able to diagnose and comprehensively treat patients with all entities of stroke, complemented by one or more smaller SC that provide care as CCC except interventional neuroradiology and neurosurgery. This system is applied in the CR. Its advantage is a wider network of stroke centers with better time accessibility (smaller distances, shorter transport from the place of occurrence of stroke to stroke center), as well as faster onset of treatment. The disadvantage is the time delay for MTE administration due to the secondary transport from a smaller to a large center. Patients who are indicated for MTE have a substantial time advantage when they are primarily transported into a large center (CCC) compared to patients primarily admitted to a smaller stroke center (SC) followed by secondary transport to the CCC. Although the triage may indicate a large artery occlusion and need for MTE, the sensitivity is only about 65–80% [28]. This issue is being discussed, and the situation is not yet clarified. The following practice is being discussed and progressively promoted in the CR—the patient is routed directly to the CCC after consultation, if there is a clear clinical suspicion of a large artery occlusion (usual symptoms of severe stroke both in carotid or vertebrobasilar circulation).

Two new clinical trials—DAWN and DEFUSE 3—demonstrated large benefit of MTE in highly selected stroke patients with large vessel occlusion in anterior circulation after 6 up to 24 h. These results could change the proportion of patients treated in CCC [29, 30]. Now, it is discussed where the diagnosis of large vessel occlusion stroke should be determined and how to select patients for MTE. Whether all SC or only CCC should be able to use advanced neuroimaging (CT perfusion/MR-DWI) is also discussed at the moment. This new situation should be reflected in future changes in SC/CCC network and EMS triaging. The optimal activity of EMS is also inevitable for the quality of stroke care [31]. EMS must be able to effectively distinguish stroke symptoms, determine their severity, optimally react in prehospital diagnostics and treatment of other medical conditions, consult with the stroke center, and transport the patient into hospital as quickly as possible. The systematical and continuous education of EMS staff in the stroke problematics is ongoing in the CR.

The main advantage of centralized stroke care is to ensure optimized personalized treatment and prevention for patients with all types of stroke, consistent with the principles of PPPM—as is the case in other areas of medicine [14, 32, 33].

The data collection of indicators of stroke care quality brings feedback to each stroke center and controls its activity and results. The data transfer of quality indicators to the Ministry of Health is an effective tool for control of stroke centers by the state authorities that can be considered as the most objective. Tracking and collecting additional indicators required by professional organization (such as RES-Q registry) brings extra significant information that can improve the quality of stroke care. The determination of type of an ischemic stroke is also important, especially for secondary prevention [5, 34]. This is related to the implementation of ECG Holter monitoring for ischemic strokes. The detection of swallowing disorder is also important for prevention and treatment of subsequent complications as well as for nursing care. In RES-Q registry, the collection of these indicators is voluntary, so it is not possible to ensure their absolute accuracy, which may give rise to the possibility of processing some untrue data.

The sharing of quality indicators among all the stroke centers in the CR is an important tool for demonstration of the quality of work of each stroke center. It can be assumed that the sharing of quality indicators can, to some extent, prevent the possible input of untrue data into the registry by an individual stroke center. Moreover, it is an effective tool for the mutual competition among stroke centers, which further improves the quality of care across the whole health system.

Expert recommendations

The centralization of stroke care ensured by legal norms (in the CR created by Ministry of Health in cooperation with a professional organization—Cerebrovascular Section of the Czech Neurological Society) has proved to be highly beneficial and effective. The crucial step is the creation of a network of stroke centers in the health care facilities (hospitals) and the EMS that performs the triage of patients with suspected stroke (recognition of stroke symptoms, prehospital diagnostic and treatment measures, consultation with the stroke center, and transfer of the patient into the specified health care facility). By the implementation of these measures, there was a significant improvement in acute stroke care in the CR (the second highest percentage of the recanalization therapy of ischemic strokes in Europe, treatment of acute stroke patients in specialized stroke units, substantial shortening of time to initiation of recanalization treatment in hospitals, diagnostics of types of ischemic strokes with significance for determining optimal secondary prevention, or screening for swallowing disorders). The registration of indicators of stroke care quality and their monitoring and reporting are the important tools for controlling of the stroke centers activities (its own internal control, as well as control by state authorities). The implementation of ECG Holter monitoring in ischemic stroke continues to improve the application of personalized treatment and targeted secondary prevention. The sharing of indicators of stroke care quality among stroke centers is an important tool for mutual competition, competitiveness, and a tool for own internal control within each center. Finally, the quality of stroke care is given also by the awareness of general practitioners and especially by the education of the population (information about stroke causes, prevention, signs and symptoms, and the optimal management of suspected stroke patient—an urgent EMS call). A number of activities on this topic are in progress in the CR, focusing on both health care workers and the general population (lectures, media information, special targeted campaigns). This comprehensive system allows for the implementation of a high standard stroke care.

At the same time, this system allows the implementation of the PPPM principles—individualized treatment of the acute stroke and other comorbidities in the acute disease stage, optimal prevention, diagnosis and treatment of possible complications, and exactly the type of stroke.

This system respects the substantial principles of personalized medicine—individualized treatment of acute stroke and other comorbidities at the acute disease stage; optimal prevention, diagnosis and treatment of possible complications; prediction of further treatment and outcome; individualized secondary prevention, exactly according to the stroke etiology. The described model of stroke care optimally meets criteria of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine (PPPM) [14, 35–38]. All these measures can be used in other countries as well to improve the quality of stroke care in general.

Authors’ contribution

JP is the project coordinator who has created the main concepts presented in the manuscript. JP, JP Jr., and VR has performed the literature search, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JP, JP Jr., and VR have designed the final version of the manuscript.

Funding information

This work was supported by MH CZ—DRO (Faculty Hospital Plzen—FNPl, 00669806), by the Charles University Research Fund (Progres Q39), and by the National Sustainability Program I (NPU I) Nr. LO1503 provided by the Ministry of Education Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. The implementation of the stroke center was supported by the European Integrated Operational Programme—Modernization and Renovation of Comprehensive Cerebrovascular Center Equipment FN Plzen (CZ.1.06/3.2.01/08.07635).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Béjot Y, Bailly H, Durier J, Giroud M. Epidemiology of stroke in Europe and trends for the 21st century. Presse Medicale Paris Fr 1983. 2016;45:e391–e398. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Registers of Stroke (EROS) Investigators. Heuschmann PU, Di Carlo A, Bejot Y, Rastenyte D, Ryglewicz D, et al. Incidence of stroke in Europe at the beginning of the 21st century. Stroke. 2009;40:1557–1563. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall IJ, Wang Y, Crichton S, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CDA. The effects of socioeconomic status on stroke risk and outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1206–1218. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golubnitschaja O, Costigliola V. EPMA. General report & recommendations in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine 2012: white paper of the European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. EPMA J. 2012;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polívka J, Rohan V, Sevčík P, Polívka J. Personalized approach to primary and secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. EPMA J. 2014;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polivka J, Krakorova K, Peterka M, Topolcan O. Current status of biomarker research in neurology. EPMA J. 2016;7:14. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Dávalos A, Ford GA, Grond M, Hacke W, Hennerici MG, Kaste M, Kuelkens S, Larrue V, Lees KR, Roine RO, Soinne L, Toni D, Vanhooren G. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2007;369:275–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, Medeghri Z, Machnig T, Schneider D, von Kummer R, Wahlgren N, Toni D, ECASS Investigators Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Yan B, Parsons MW, Christensen S, Churilov L, Dowling RJ, Dewey H, Brooks M, Miteff F, Levi C, Krause M, Harrington TJ, Faulder KC, Steinfort BS, Kleinig T, Scroop R, Chryssidis S, Barber A, Hope A, Moriarty M, McGuinness B, Wong AA, Coulthard A, Wijeratne T, Lee A, Jannes J, Leyden J, Phan TG, Chong W, Holt ME, Chandra RV, Bladin CF, Badve M, Rice H, de Villiers L, Ma H, Desmond PM, Donnan GA, Davis SM, EXTEND-IA investigators A multicenter, randomized, controlled study to investigate EXtending the time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits with Intra-Arterial therapy (EXTEND-IA) Int J Stroke Off J Int Stroke Soc. 2014;9:126–132. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DWJ, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, Dávalos A, Majoie CBLM, van der Lugt A, de Miquel MA, Donnan GA, Roos YBWEM, Bonafe A, Jahan R, Diener HC, van den Berg LA, Levy EI, Berkhemer OA, Pereira VM, Rempel J, Millán M, Davis SM, Roy D, Thornton J, Román LS, Ribó M, Beumer D, Stouch B, Brown S, Campbell BCV, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Saver JL, Hill MD, Jovin TG. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;387:1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener H-C, Levy EI, Pereira VM, et al. Solitaire™ with the intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke (SWIFT PRIME) trial: protocol for a randomized, controlled, multicenter study comparing the Solitaire revascularization device with IV tPA with IV tPA alone in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke Off J Int Stroke Soc. 2015;10:439–448. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarbrough CK, Ong CJ, Beyer AB, Lipsey K, Derdeyn CP. Endovascular thrombectomy for anterior circulation stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2015;46:3177–3183. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, Fang MC, Fisher M, Furie KL, Heck DV, Johnston SC, Kasner SE, Kittner SJ, Mitchell PH, Rich MW, Richardson D, Schwamm LH, Wilson JA, on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EPMA World Congress Traditional Forum in Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine for Multi-Professional Consideration and Consolidation. EPMA J. 2017;8:1–54. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Věstník č. 8/2010 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.mzcr.cz/Legislativa/dokumenty/vestnik-c_4025_1770_11.html

- 16.Věstník č. 2/2010 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.mzcr.cz/Legislativa/dokumenty/vestnik-c_3703_1770_11.html

- 17.Věstník č. 10/2012 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.mzcr.cz/Legislativa/dokumenty/vestnik-c10/2012_7175_2510_11.html

- 18.Věstník č. 11/2015 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.mzcr.cz/Legislativa/dokumenty/vestnik-c11/2015_10551_3242_11.html

- 19.Berglund A, Svensson L, Wahlgren N, von Euler M, HASTA collaborators Face arm speech time test use in the prehospital setting, better in the ambulance than in the emergency medical communication center. Cerebrovasc Dis Basel Switz. 2014;37:212–216. doi: 10.1159/000358116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Home - ESO Quality Registry [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.qualityregistry.eu/index.php/cs/

- 21.De Raedt S, De Vos A, Van Binst A-M, De Waele M, Coomans D, Buyl R, et al. High natural killer cell number might identify stroke patients at risk of developing infections. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2015;2:e71. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Registries | SITS International [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: https://sitsinternational.org/registries/

- 23.Czech Health Statistics Yearbook | ÚZIS ČR [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.uzis.cz/en/catalogue/czech-health-statistics-yearbook

- 24.Eurostat [Internet]. [cited 2018 Sep 9]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/home

- 25.Maaijwee NAMM, Rutten-Jacobs LCA, Schaapsmeerders P, van Dijk EJ, de Leeuw F-E. Ischaemic stroke in young adults: risk factors and long-term consequences. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:315–325. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thom V, Schmid S, Gelderblom M, Hackbusch R, Kolster M, Schuster S, Thomalla G, Keminer O, Pleß O, Bernreuther C, Glatzel M, Wegscheider K, Gerloff C, Magnus T, Tolosa E. IL-17 production by CSF lymphocytes as a biomarker for cerebral vasculitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2016;3:e214. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorfler A. Comprehensive interventional stroke therapy: patient selection, interdisciplinary workflow aspects and state-of-the-art technique. 26. European Stroke Conference, 24 - 26 May, Berlin; 2017.

- 28.Smith EE, Kent DM, Bulsara KR, Leung LY, Lichtman JH, Reeves MJ, Towfighi A, Whiteley WN, Zahuranec DB, American Heart Association Stroke Council Accuracy of prediction instruments for diagnosing large vessel occlusion in individuals with suspected stroke: a systematic review for the 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:e111–e122. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, Bonafe A, Budzik RF, Bhuva P, Yavagal DR, Ribo M, Cognard C, Hanel RA, Sila CA, Hassan AE, Millan M, Levy EI, Mitchell P, Chen M, English JD, Shah QA, Silver FL, Pereira VM, Mehta BP, Baxter BW, Abraham MG, Cardona P, Veznedaroglu E, Hellinger FR, Feng L, Kirmani JF, Lopes DK, Jankowitz BT, Frankel MR, Costalat V, Vora NA, Yoo AJ, Malik AM, Furlan AJ, Rubiera M, Aghaebrahim A, Olivot JM, Tekle WG, Shields R, Graves T, Lewis RJ, Smith WS, Liebeskind DS, Saver JL, Jovin TG, DAWN Trial Investigators Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, Christensen S, Tsai JP, Ortega-Gutierrez S, McTaggart R, Torbey MT, Kim-Tenser M, Leslie-Mazwi T, Sarraj A, Kasner SE, Ansari SA, Yeatts SD, Hamilton S, Mlynash M, Heit JJ, Zaharchuk G, Kim S, Carrozzella J, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, Bammer R, Lavori PW, Broderick JP, Lansberg MG, DEFUSE 3 Investigators Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:708–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krebs W, Sharkey-Toppen TP, Cheek F, Cortez E, Larrimore A, Keseg D, Panchal AR. Prehospital stroke assessment for large vessel occlusions: a systematic review. Prehospital Emerg Care Off J Natl Assoc EMS Physicians Natl Assoc State EMS Dir. 2018;22:180–188. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2017.1371263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polivka J, Kralickova M, Polivka J, Kaiser C, Kuhn W, Golubnitschaja O. Mystery of the brain metastatic disease in breast cancer patients: improved patient stratification, disease prediction and targeted prevention on the horizon? EPMA J. 2017;8:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0087-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polivka J, Altun I, Golubnitschaja O. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer: the risky status quo and new concepts of predictive medicine. EPMA J. 2018;9:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13167-018-0129-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hankey GJ. Secondary stroke prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:178–194. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pastukhov A, Krisanova N, Maksymenko V, Borisova T. Personalized approach in brain protection by hypothermia: individual changes in non-pathological and ischemia-related glutamate transport in brain nerve terminals. EPMA J. 2016;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helms TM, Duong G, Zippel-Schultz B, Tilz RR, Kuck K-H, Karle CA. Prediction and personalised treatment of atrial fibrillation-stroke prevention: consolidated position paper of CVD professionals. EPMA J. 2014;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunner-La Rocca H-P, Fleischhacker L, Golubnitschaja O, Heemskerk F, Helms T, Hoedemakers T, et al. Challenges in personalised management of chronic diseases-heart failure as prominent example to advance the care process. EPMA J. 2015;7:2. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alamri Y. Current patterns of collaboration in published neurology research: author collaboration in neurological research. EPMA J. 2017;8:207–209. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]