Abstract

Older adults are underrepresented in research, and a potential barrier to their participation may be the increasing prevalence of vision loss and lack of accommodation for this challenge. Although vision loss may initially pose a challenge to research participation, its effects can be mitigated with early, in-depth planning. For example, recruitment is more inclusive when best practices identified in the literature are used in the preparation of written materials to reduce glare and improve readability and legibility. Alternatives to obtaining written consent may be used. Interviews are made accessible when done verbally and the author uses cueing and good diction. Remaining vision can be optimized through seating arrangement, lighting, and magnification. Challenges encountered and resolved in a recent study with severely visually impaired older adults are offered here as exemplars. Methodology for identifying and recruiting a sample comprised exclusively of visually impaired older adults is also offered herein.

Keywords: AMD, age-related macular degeneration, vision impairment, research methods, best practices, older adults, research participation, recruitment, low vision accommodation, low vision, gerontology, visually impaired older adults

In the United States, the population of older adults (aged 65 years and older) is increasing in number and is expected to reach 83.7 million by 2050 (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). Despite these numbers, older adults continue to be underrepresented in research (Mody et al., 2008). Underrepresentation has serious consequences for older adults because clinical treatments are often based on studies involving younger, healthier, higher functioning samples. A potential barrier to research participation among older adults may be the prevalence of vision loss and lack of accommodation of this challenge.

Vision loss increases with age among all demographics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). The most common causes of vision loss are cataracts, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD; CDC, 2011), all of which are either exclusive to older individuals or dramatically increase with age. Although cataracts are highly treatable, glaucoma and AMD may lead to irreversible vision loss. Owing to the aging of the general U.S. population, cases of glaucoma are expected to reach 5.5 million by 2050, an increase of more than 90% from 2014 (Wittenborn & Rein, 2014). Cases of AMD, the leading cause of irreversible blindness, are expected to double to 17.8 million by 2050 (Wittenborn & Rein, 2014). By taking steps to make research participation more accessible and inclusive of those with vision impairment, we may increase the overall participation of older adults, improving the quality and quantity of research to meet the needs of this growing population.

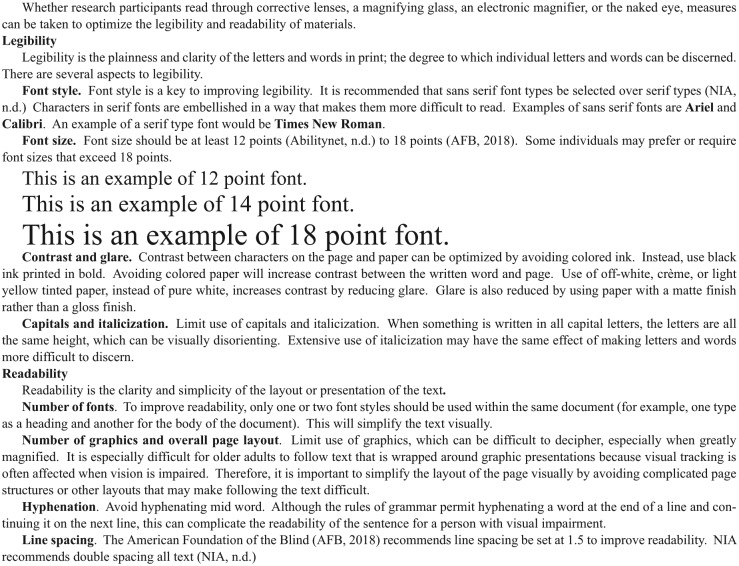

The purpose of this article is to present a recent study involving older adults with severe vision impairment as an exemplar, including strategies related to recruitment, preparation of written study materials, obtaining consent, and data collection. We will discuss challenges encountered and our recommendations for those who wish to accommodate visually impaired research participants. Finally, we offer our recommended best practices for the preparation of written materials, a compilation of what is laid forth by Abilitynet (n.d.), the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB; 2018), and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health (n.d.; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Best practice recommendations for preparation of written study materials.

Note. Recommendations taken from Abilitynet (n.d.), the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB; 2018), and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health (n.d.). We assessed some recommendations which were offered for web-based materials and applied them as we judged appropriate and relevant to written materials.

Exemplar Study Overview: Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) Among Older Adults With AMD

The study, Posttraumatic Growth among Older Adults with Age-Related Macular Degeneration, was a descriptive, correlational study using a mixed-methods approach and cross-sectional design. Eighty-nine severely visually impaired older adults were interviewed about their experience with vision loss caused by AMD. The study aims were not only to measure and describe the extent to which PTG occurred in this sample but also to describe demographic correlates of PTG and perceived stressfulness of vision loss, social support, and depression and their relationship to PTG. In addition to collecting quantitative data using a composite questionnaire, qualitative interviews were used to highlight exemplars of growth and to understand better the experience of the struggle with vision loss and how it may lead to PTG among older adults with severe AMD. Institutional review board (University of Utah IRB Approval, IRB_00080324) approval for this study was obtained and included the specifics of the low vision accommodations described below.

Data collection occurred in two phases. First, an interviewer administered an 84 question composite questionnaire comprised of demographic questions, the Event-Related Rumination Inventory (ERRI; Cann et al., 2011), the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Yesavage et al., 1982), Lubben’s Social Network Scale (SNS; Lubben, 1988), two questions about Perceived Stressfulness, as well as a question about Religiosity. Next, in-depth, semistructured interviews were conducted among 15 individuals who scored positively on the PTGI, to be used as exemplars of the growth process.

Recruitment Exemplar: Identifying and Refining a Pool of Visually Impaired Potential Participants

The study was conducted at a large, multisite ophthalmology clinic which hosts more than 120,000 patient visits per year, including more than 6,000 surgeries. To identify and refine a pool of potential participants, we queried medical records. We began by excluding potential participants who had received their diagnosis of permanent vision loss less than 6 months prior to recruitment for the study. This decision was made to respect potential participants’ need for an adjustment period before being approached to participate in a research study, as suggested by Kleinschmidt et al. (1995). Inclusion criteria were aged 65 years of age or older, visual acuity no better than 20/70 best corrected vision in either eye, and a diagnosis of AMD. Potential participants who had been diagnosed with any other blinding condition were excluded.

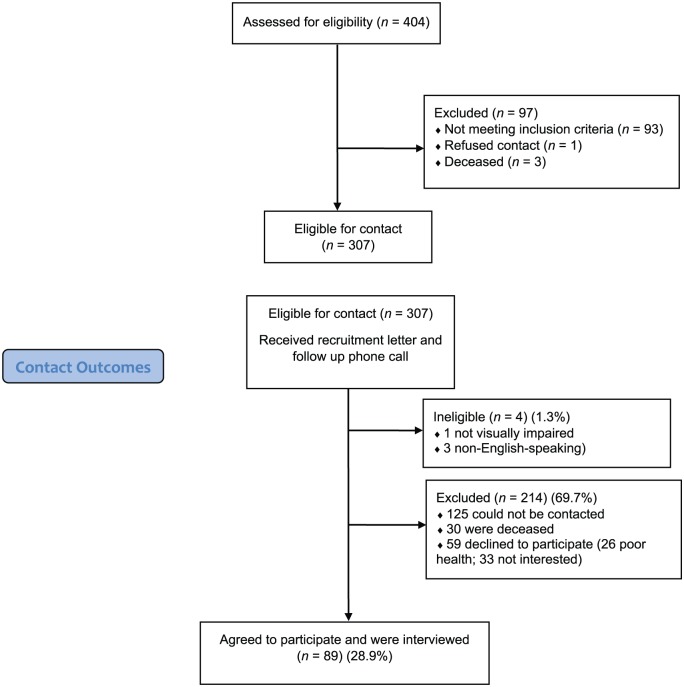

The initial query of the medical records yielded 243 names. The search to identify potential participants was blunted because the programming could not identify patients whose visual acuity was notated in a nonnumeric way (e.g., HM [hand motion] or CF [counts fingers]). These patients were identified by hand from the medical record to yield an additional 161 participants for a total of 404 potential participants. The two-step process of identifying eligible persons and confirming which eligible person would participate is outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Recruitment.

Of the initial 404 potential participants identified, one was removed due to a notation in the medical record indicating they did not want to be contacted for research purposes. After further review, we discovered that three potential participants were deceased. Because we sought to measure the effects of only AMD on our outcome variable, the medical record was reviewed by hand to identify participants who had additional ocular diagnoses that would exclude them. Those not meeting the eligibility criteria (n = 93) were excluded for the following reasons: glaucoma, 40; preglaucoma/borderline glaucoma, 10; diabetes, five; cornea, 18; herpetic infections, two; benign neoplasm of choroid, seven; other, 11.

The remaining 307 potential participants received a recruitment letter and follow-up phone call. One was ineligible due to not being visually impaired, 125 could not be contacted, three were non-English speaking, 30 were deceased, and 59 declined to participate (26 poor health, 33 not interested). Thus, 89 participants were enrolled in the study and interviewed.

Challenges, Strategies, and Recommendations

Study Material Exemplar

For our study, written recruitment materials were printed on off-white, low-glare (matte) paper, in 18-point Arial font printed in black bold (see Figure 1). We were mindful to include graphics only in the header, in the form of the university logo, and to use only one font type. We did not use italics or all caps in the document and used the AFB recommendation to set the line spacing at 1.5 (see Figure 1). The materials were well received by participants, many of whom expressed appreciation for the efforts we took to make the materials more accessible for visually impaired persons.

Recruitment letters were sent to the home addresses of potential participants, who then received a follow-up phone call within 1 week. This method posed an unanticipated problem unrelated to vision impairment. Mody et al. (2008) indicated that a potential barrier to recruitment among older adults is the increasing awareness of “scams.” The recruitment letter indicated that we had identified potential participants through their eye care provider. Some potential participants were suspicious that the study was a scam, and wanted to confirm with the clinical site that this was a legitimate study. Unfortunately, rather than calling the contact number listed on the letter, potential participants called any one of numerous numbers at the clinical site to inquire about the study and were occasionally given inaccurate information. This issue was recognized early and was resolved by including (with the recruitment materials) a letter, on clinic letterhead, substantiating the legitimacy of the study, with contact information for someone at the clinic site who could field questions and refer them to the researcher.

Issues Related to Data Collection

Many studies have shown that older adults who have AMD have greater difficulty driving than those without AMD (Owsley & McGwin, 2008). In focus groups whose purpose was to discuss participants’ vision, the most commonly cited problem involving participants with both severe AMD and early AMD was driving (Mangione et al., 1998; Owsley, McGwin, Scilley, & Kallies, 2006). Therefore, with IRB approval, consent was obtained and interviews were conducted via telephone, bypassing the need for participants to travel to participate. Telephone interviews also allowed for increased flexibility in scheduling, as well as providing a more comfortable setting for participants. Given the severity of the impairment levels, the telephone interviews (as opposed to being requested to complete self-administered questionnaires) provided a more accessible way for participants with vision impairment to participate in the study.

Completing the lengthy, 84-question, composite questionnaire nonvisually posed an unanticipated challenge to both research participants and interviewer. When a survey is completed visually, the participant can easily gauge the length of the survey as well as progress made. Although our participants were aware that the questionnaire was comprised of 84 questions and were given an estimated time by which the interview would be completed, they seemed frustrated and discouraged by about halfway through, asking “How many more questions?” “How much longer?” or even opting to discontinue the interview, when it was nearly complete. This problem was recognized early, and in response, modifications were made to the script, which allowed the interviewer to pause several times during the interview and let the participant know where they were in the process and how many questions remained. The problem was considered solved because there were no more complaints about the length of the interview or anxiety about the effort remaining and all questionnaires were completed.

Eighty-six (96.6%) participants completed the interviews in a single session, lasting approximately 45 min, while two (2.2%) participants required two sessions (1 day apart)—one for a scheduling conflict and another because of fatigue. One (1.1%) participant needed three sessions (1 day apart) to complete the interview, due to her long, descriptive responses to interview questions. Upon review of the completed questionnaires, four (4.5%) were identified that had missing responses, which were recaptured by contacting the participants to obtain their responses to the missing items. This procedure was consistent with the IRB approved research proposal. The main outcome measure of the study, the 21 item PTGI (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), was found to be highly reliable (α = .92).

Additional insights into interviewing older adults with vision impairment are offered by Moore (2002), gleaned from her experience with face-to-face qualitative interviews. She conducted all in-depth interviews at the homes of participants and emphasized that seating arrangement for the interviews should be matched to participant preference, to optimize the participant’s remaining vision, including reducing glare and allowing for the adjustment of lighting. She obtained consent at the research participant’s homes at the time of her interviews and audio recorded their verbal response, to document consent.

In addition, she referred to general guidelines found in the gerontological literature for communicating with visually impaired older adults, including speaking distinctly and clearly, wearing bright colors with bold contrasts, and using good lighting (Lueckenotte, 1996; Tyson & Tyson, 1999).

Additional Issues Related to Obtaining Consent

The mean age of participants in our study was 85. An issue we did not predict, unrelated to vision loss, but likely related to the advanced age of our sample, involved adult children of potential participants. Occasionally, after recruitment letters were sent, we received a phone call from an adult child of the potential participant, indicating that their parent would like to participate in the study. At times, they would attempt to be very involved, even offering to give consent or answer study questions on behalf of their parent. We assessed each situation carefully, by inquiring further of the potential participant themselves, occasionally discovering that the potential participant was compromised in such a way that precluded their participation in the study; for example, they may have had dementia so severe that they could not follow a conversation or they may have had some other severe impediment. In cases where the potential participant was able to participate, we ensured that consent was properly obtained as outlined earlier.

Conclusion

Vision impairment may pose a significant barrier to research participation among older samples; two thirds of persons with vision impairment are older adults (NIA, National Institutes of Health, n.d.). We know that this issue is not resolving quickly because a well-documented trend indicates that there is a continuously growing number of seniors with severe age-related eye conditions (National Eye Institute, n.d.). Although vision loss poses a potentially significant barrier to the participation of older adults in research studies, its effects can be mitigated with early, in-depth planning, including improving readability and legibility of written materials (AFB, 2018; NIA, National Institutes of Health, n.d.; Figure 1), using alternate ways of obtaining and confirming consent (Moore, 2002), and collecting data in a way that allows participants to engage in research from home, if travel is difficult (Moore, 2002). Accommodating visually impaired older adults in research studies will allow us to improve both the quality and quantity of research studies to meet the demands of our aging population.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research has been supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research Grant # T32NR013456.

ORCID iD: Corinna Trujillo Tanner  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8969-2853

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8969-2853

References

- Abilitynet. (n.d.). Producing accessible materials for print and online. Retrieved from https://www.abilitynet.org.uk/quality/documents/StandardofAccessibility.pdf

- American Foundation for the Blind. (2018). Tips for making print more readable. Retrieved from http://www.afb.org/info/living-with-vision-loss/reading-and-writing/making-print-more-readable/235

- Cann A., Calhoun L. G., Tedeschi R. G., Triplett T. V., Vishnevsky T., Lindstrom C. M. (2011). Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: The Event Related Rumination Inventory. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 24, 137-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). The state of vision, aging, and public health in America. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt J. J., Trunnell E. P., Reading J. C., White G. L., Richardson G. E., Edwards M. E. (1995). The role of control in depression, anxiety, and life satisfaction among visually impaired older adults. Journal of Health Education, 26, 26-36. doi: 10.1080/10556699.1995.10603073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubben J. E. (1988). Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance, 11(3), 42-52. [Google Scholar]

- Lueckenotte A. G. (1996). Gerontological nursing. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Mangione C. M., Berry S., Spritzer K., Janz N., Klein R., Owsley C., Owl P. (1998). Identifying the content area for the 51-item National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire: Results from focus groups with visually impaired persons. Archives of Ophthalmology, 116(2), 227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody L., Miller D. K., McGloin J. M., Freeman M., Marcantonio E. R., Magaziner J., Studenski S. (2008). Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 56, 2340-2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L. W. (2002). Conducting research with visually impaired older adults. Qualitative Health Research, 12, 559-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Eye Institute. (n.d.). Statistics and data. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/

- National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Making your website senior friendly. Retrieved from www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/checklist.pdf

- Ortman J., Velkoff V., Hogan H. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved from http://bowchair.com/uploads/.9/8/4/9/98495722/.agingcensus.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C., McGwin G., Jr. (2008). Driving and age-related macular degeneration. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 102, 621-635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C., McGwin G., Jr., Scilley K., Kallies K. (2006). Development of a questionnaire to assess vision problems under low luminance in age-related maculopathy. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 47, 528-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R. G., Calhoun L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Trauma Stress, 9, 455-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson S. R., Tyson S. L. (1999). The five senses: Sensation and perception. In Tyson S. R. (Ed.), Gerontological nursing care (p. 166). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenborn J., Rein D. (2014, June 11). The future of vision: Forecasting the prevalence and costs of vision problems. Paper presented at Prevent Blindness, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage J. A., Brink T. L., Rose T. L., Lum O., Huang V., Adey M., Leirer V. O. (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]