Abstract

Objectives:

The Care and Prevention in the United States Demonstration Project included implementation of a Data to Care strategy using surveillance and other data to (1) identify people with HIV infection in need of HIV medical care or other services and (2) facilitate linkages to those services to improve health outcomes. We present the experiences of 4 state health departments: Illinois, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Methods:

The 4 state health departments used multiple databases to generate listings of people with diagnosed HIV infection (PWH) who were presumed not to be in HIV medical care or who had difficulty maintaining viral suppression from October 1, 2013, through September 29, 2016. Each health department prioritized the listings (eg, by length of time not in care, by viral load), reviewed them for accuracy, and then disseminated the listings to staff members to link PWH to HIV care and services.

Results:

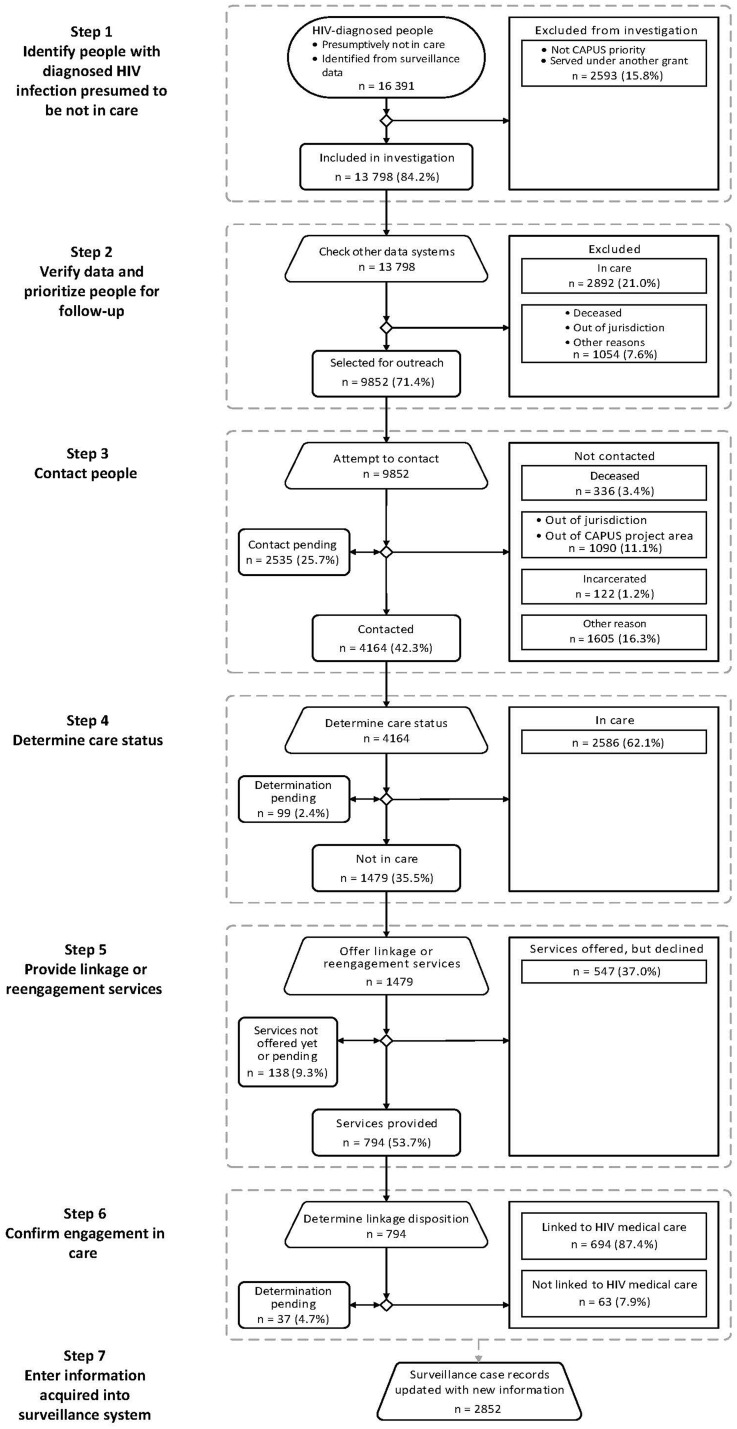

Of 16 391 PWH presumed not to be in HIV medical care, 9852 (60.1%) were selected for follow-up; of those, 4164 (42.3%) were contacted, and of those, 1479 (35.5%) were confirmed to be not in care. Of 794 (53.7%) PWH who accepted services, 694 (87.4%) were linked to HIV medical care. The Louisiana Department of Health also identified 1559 PWH as not virally suppressed, 764 (49.0%) of whom were eligible for follow-up. Of the 764 PWH who were eligible for follow-up, 434 (56.8%) were contacted, of whom 269 (62.0%) had treatment adherence issues. Of 153 PWH who received treatment adherence services, 104 (68.0%) showed substantial improvement in viral suppression.

Conclusions:

The 4 health departments established procedures for using surveillance and other data to improve linkage to HIV medical care and health outcomes for PWH. To be effective, health departments had to enhance coordination among surveillance, care programs, and providers; develop mechanisms to share data; and address limitations in data systems and data quality.

Keywords: HIV, HIV surveillance, Data to Care, Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund, Care and Prevention in the United States Demonstration Project

People with diagnosed HIV infection (PWH) who receive treatment can improve their health outcomes by maintaining viral suppression and preventing further transmission. Goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and other HIV prevention goals have focused on increasing access to HIV care and treatment and improving health outcomes for PWH.1,2 The Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project (hereinafter, CAPUS) was a 4-year (2012-2016), cross-agency demonstration project funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The primary goals of CAPUS were to (1) increase the proportion of racial/ethnic minority groups whose HIV infection was diagnosed and (2) optimize linkage to, retention in, and reengagement in care for people with newly diagnosed HIV infection or previously diagnosed HIV infection by addressing social, economic, clinical, and structural factors that influence HIV health outcomes. CAPUS funded 8 state health department programs to improve HIV care and prevention outcomes by using HIV surveillance and other data.3,4

Health departments use HIV surveillance data to monitor trends in HIV diagnoses, stage the progression of disease, and describe the epidemiology of HIV disease; they also may use these data for public health interventions.2,5-7 Data to Care (D2C) is a high-impact public health strategy that uses HIV surveillance and other data to identify PWH who are in need of HIV medical care and other services and link them to those services.8-10 D2C programs at each health department use CD4+ T-lymphocyte (CD4) and HIV viral load laboratory data routinely reported through HIV surveillance as markers of HIV care.2,11 PWH without reported test results during a specified period are classified as not in care. D2C programs follow up with PWH not in care and offer to help link them to medical care or reengage them with medical care. In addition, D2C programs may identify PWH who are in care but who have persistently high (ie, unsuppressed) viral load results and offer treatment adherence support or other services. This article summarizes the experiences of 4 of the 8 CAPUS grantees—the state health departments of Illinois, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia—that initiated their D2C programs earlier and reported complete data while CAPUS was implemented.

Materials and Methods

Preimplementation Activities

The 4 health departments began preparing for D2C activities as early as 2011. These pre-CAPUS activities were implemented by using funds from other HIV prevention and care projects supported by CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The Illinois, Louisiana, and Tennessee state health departments focused on HIV medical care engagement activities, and the Virginia Department of Health focused on planning and developing an integrated Care Markers Database.

During preimplementation, D2C programs evaluated laboratory reporting laws and procedures, quality and completeness of HIV surveillance and laboratory data, and availability of additional data sources. All 4 health departments had requirements in place in 2012 or earlier for reporting CD4 and HIV viral load test results as part of routine surveillance activities.12 Each health department reviewed data-sharing laws and policies and the need for new data-sharing agreements and partnerships, and prioritized data (eg, by length of time not in care, by viral load) to generate lists of PWH who were not in care (ie, not-in-care lists). The health departments found that memoranda of understanding as well as data-sharing, coordinated-care, and services agreements were important for initiating D2C processes. D2C programs leveraged partnerships with medical facilities, HRSA-funded Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program care providers, and community-based organizations—particularly those with patient navigation programs—to conduct investigations and linkage activities, identify resources and technical assistance needs, and minimize duplication of services. D2C programs also held partner meetings to increase awareness and buy-in of D2C initiatives. CDC determined this project constituted nonresearch activity; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

Implementation Activities

The Illinois, Louisiana, and Tennessee state health departments implemented the project during a 3-year period (2013-2016), and the Virginia Department of Health implemented the project during a 2-year period (2014-2016). D2C implementation activities included establishing a not-in-care definition and generating and cleaning the not-in-care list, prioritizing and disseminating the not-in-care list for program follow-up (Table 1), and providing linkage and reengagement services to PWH not in care (Table 2).

Table 1.

Implementation activities for surveillance-based identification of people with diagnosed HIV infection who were not in care (Data to Care [D2C]a), Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project,b 4 states, 2013-2016c

| Implementation Activities | Illinois | Louisiana | Tennessee | Virginia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishing a not-in-care definitiond | ||||

| Initial definition | PWH with no HIV viral load or CD4 laboratory test entered in eHARSe in the past 12 months | PWH diagnosed with HIV infection within the past 12 months who had not entered into care 6-12 months after diagnosis and PWH (regardless of diagnosis date) who had not had a CD4 count or viral load taken in 12-36 months (definition used from October 1, 2013, through May 15, 2015) | PWH with at least 1 HIV test result entered in eHARSe during the past 3 years (eg, January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2012) but with no evidence of any HIV care (indicated by a CD4 or viral load entry) during the most recent calendar year | PWH who had no evidence of HIV care during a reference calendar year |

| Subsequent definition | PWH for whom no viral load or CD4 laboratory test was present in eHARSe for the 12-month period before the query date and for whom there was no documentation of the following: a medical visit, a viral load or CD4 result within a Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program or AIDS Drug Assistance Program, or continuation of health insurance program record for the 12-month period before the query date | PWH diagnosed with HIV infection within the past 9 months who had not entered into care 6-9 months after diagnosis and PWH (regardless of diagnosis date) who had not had a CD4 count or viral load taken in 9-36 months (definition used since May 16, 2015) | Definition did not change. | PWH who had evidence of HIV care in a reference calendar year but none in the subsequent year (eg, PWH who had evidence of care in 2014 but not in 2015) |

| Generating and cleaning the not-in-care list | ||||

| Database(s) used to compile list of PWH who were not in care and frequency of generating the list | Generated primarily from eHARSe; planned to be updated monthly but took 1 year to go through initial list | Compiled from eHARS,e HIV laboratory registry, and PRISMf,14; automated SASg,15 program added new PWH, removed PWH no longer meeting eligibility criteria, and updated alerts for PWH currently under investigation; generated weekly | Generated primarily from eHARSe; generated annually | Generated from Care Markers Database, which was created by combining data from multiple sources; generated biannually |

| Additional data sources used to verify and clean data | Internet search tools (eg, Google.com, dogpile.com, Zillow.com, Facebook.com) and online public records (eg, county property tax records, pet register, Medicaid card records, obituaries, Department of Corrections inmate listings) | A commercially available people-search tool was used to identify deaths or additional address and telephone information. | PRISMf, 14; Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program clinical and support service systems; the health department’s patient tracking and billing system, TennCare (Tennessee’s Medicaid program); and a commercially available people-search tool | Maryland and District of Columbia surveillance databases, a commercially available people-search tool, Care Markers Database (HIV care, prevention, surveillance, and Medicaid data sources), and VineLink (online portal to search for the current custody status of inmates) |

| Prioritizing and disseminating the not-in-care list for program follow-up | ||||

| Prioritization of PWH for follow-up | PWH in approximately 89 counties with low HIV incidence were prioritized for CAPUS referrals because all health departments in high-HIV-incidence counties had already been funded to conduct surveillance-based services. | People newly diagnosed with HIV and not linked to care, PWH who had fallen out of care, or PWH not linked to care for an extended period of time: ascending order by time not in care and viral suppression status at last viral load test PWH with virologic failure (ie, 2 recent viral load test results >1000 copies/mL): descending order by first viral load of pair PWH with a viral load >500 000 copies/mL with no subsequent test within 3 months: descending order by last viral load |

By geography—each D2C specialist received a list of PWH for their region. Because of limited funding, not all regions could be assigned a D2C specialist, but specialists were located in the regions with the highest incidence of HIV and were able to cover 80% of not-in-care PWH on their statewide list. All PWH on the list were eventually investigated. | Initially, health districts with the highest numbers of not-in-care PWH or districts where specialists were available to conduct investigations were prioritized. Later, PWH seen by agencies with HIV care and/or prevention contracts with the Virginia Department of Health were prioritized. |

| Distribution of lists for follow-up | Referral lists were uploaded into the program management application system (Provide Enterpriseh,16,17) and sent to the appropriate provider based on the designated regional jurisdiction. | Referral list was exported to a database, and notifications were generated to alert linkage-to-care coordinators about individuals’ dispositions or newly reported surveillance information. | Referral list was manually provided to the disease intervention specialist, who would apply additional cross-checks and matches in other databases. | Referral list was separated by facility and distributed to the appropriate facility for follow-up. |

Abbreviations: CD4, CD4+ T-lymphocyte; D2C, Data to Care; eHARS, Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System; PRISM, Patient Reporting Investigation Surveillance Manager; PWH, people with diagnosed HIV infection.

a D2C is a high-impact public health strategy that uses HIV surveillance and other data to identify PWH who are in need of HIV medical care and other services and link them to those services.8

b The CAPUS Demonstration Project was a 4-year, cross-agency demonstration project funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).3

c The time period covered was October 1, 2013, through September 29, 2016, for state health departments in Illinois, Louisiana, and Tennessee, and January 1, 2015, through September 29, 2016, for the Virginia Department of Health.

dIllinois updated its definition to include review of Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and AIDS Drug Assistance Program documentation to better assess whether PWH were truly not in care and in need of follow-up. Virginia updated its definition to having care in one reference year and not the following year to identify PWH who were potentially more recently out of care and to reduce the number of PWH identified as in need of follow-up. Louisiana updated its definition to reach PWH who may be out of care sooner rather than later.

e eHARS is a browser-based, CDC-developed application that assists health departments with reporting, data management, analysis, and transfer of data to CDC.13

f PRISM is a software system used by some sexually transmitted disease/HIV programs to support partner services, surveillance, and case management.14

g SAS Institute, Inc.15

Table 2.

Linkage to and reengagement in care of people with diagnosed HIV infection who were not in HIV care using the Data to Care (D2C)a process, Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project,b 4 states, 2013-2016c

| Engagement-in-Care Activities | Illinois | Louisiana | Tennessee | Virginia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial contact with PWH for linkage to or reengagement in HIV medical care | In-person contact between PWH and surveillance-based service providers involved verification of identity and assessment of care status, risk behaviors, and service needs. | In-person contact between PWH and linkage-to-care coordinators involved assessment of barriers to care and other challenges. | Contact between PWH and D2C specialists involved the assessment of service needs and barriers to accessing care. | Contact involved assessment of a person’s willingness to link to or reengage in care and complete the health department’s Coordination of Care and Services Agreement. |

| Definition of linkage to and reengagement in care | Person attended the first HIV medical care appointment. | Evidence of CD4 or viral load test results after enrollment in health department–sponsored HIV medical linkage program. | Person attended the first HIV medical care appointment, and the health department received the person’s CD4 and viral load test results. | Evidence of a care marker (eg, CD4 or viral load test result, HIV medical care visit, or antiretroviral therapy prescription) in program or surveillance data. |

| Follow-up services offered to PWH during linkage to and reengagement in care | Some services (eg, partner services) were provided by the health department; referrals to other service providers were made depending on need; surveillance-based service providers often attended the first HIV medical care appointment for PWH. | Linkage-to-care coordinators made initial appointments and accompanied PWH to Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program case management and/or laboratory appointments; linkage-to-care coordinators stayed in contact with PWH and provided assistance to meet service needs. | Barriers to care were addressed before linkage attempts (up to 5 attempts were made); D2C specialists arranged and attended the first HIV medical care appointments of PWH and followed up after initial linkage when needed. | First HIV medical appointment was confirmed on Coordination of Care and Services Agreement form, but patient navigation specialists confirmed the appointments of PWH for 18 months. |

| Time between linkage and reengagement attempts and case closeout | 45 days if possible; extension provided as needed | At least 90 days; linkage-to-care coordinators could close the follow-up process at their discretion for up to 1 year; extension beyond the initial 90 days was necessary because of the lengthy process of locating or contacting PWH | 3-9 months, depending on the needs and cooperation of PWH; addressing barriers and other service needs took time before linkage occurred | 60 days per person to locate and reengage PWH with care |

| Tracking information from the linkage and reengagement process | Program activities and outcomes were tracked in a program management application (Provide Enterprised, 16,17), the same system used to distribute case information. | CAREWaree, 18 was used to capture process and outcome data, including enrollment, intake, services, and discharges; a referral list program was used to track progress, such as contact attempts and outcomes data. | PRISMf, 14 was used to capture case management details; Excel spreadsheets were used to summarize activities and track progress. | Program data were collected with a D2C collection tool and entered into the state’s Care Markers Database. |

| Challenges during linkage and reengagement | Initial protocol that allowed simultaneous referral by surveillance-based service providers to case management and a physician led to conflicting reports about whether PWH were in care; surveillance data were incomplete for determining care status. | Engaging PWH with complex challenges was time- and resource-intensive. | Engaging PWH with HIV medical care took longer than expected; PRISMf, 14 and Excel spreadsheets were not efficient for tracking reengagement activities. | Facilities had conflicting policies and practices for following up with PWH. Locating PWH was also a challenge. |

| Lessons learned during linkage and reengagement | Revised protocol to designate case managers as solely responsible for engagement with care; surveillance data must be cross-referenced with other care records. | Engagement with care could be addressed only after other immediate challenges were addressed; PWH were offered referral or navigation services to meet other needs (eg, transportation, housing). | Time required to engage PWH in care necessitated a reduction in caseloads per specialist; important to address how to effectively track linkage and reengagement activities before launching D2Ca program. | Linkage and reengagement required dedicated staff members; linkage staff members gathered new information on forms, passed the completed forms to surveillance staff members, and surveillance staff members entered the new data into the Care Markers Database. |

Abbreviations: PRISM, Patient Reporting Investigation Surveillance Manager; PWH, people with diagnosed HIV infection.

a D2C is a high-impact public health strategy that uses HIV surveillance and other data to identify PWH who are in need of HIV medical care and other services and link them to those services.8

b The CAPUS Demonstration Project was a 4-year cross-agency demonstration project funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).3

c The time period covered was October 1, 2013, through September 29, 2016, for state health departments in Illinois, Louisiana, and Tennessee, and January 1, 2015, through September 29, 2016, for the Virginia Department of Health.

d Provide Enterprise care management software is a relational database used by some programs to manage care, prevention, and social service data.16,17

e CAREWare is an electronic health and social support services information system for Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program grant recipients and their providers that was developed by the HIV/AIDS Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration.18

f PRISM is a software system used by some sexually transmitted disease/HIV programs to support partner services, surveillance, and case management.14

The health departments used various definitions to identify PWH as not in care. However, all 4 departments used the following criteria to identify PWH as not in care: currently alive, an HIV diagnosis or laboratory test reported within a certain period, and no evidence of HIV care (ie, no reported CD4 or viral load test) during a defined reference period (the number of months in each period varied by health department). The Illinois and Virginia state health departments also incorporated documentation of a medical visit or a prescription for antiretroviral therapy into their not-in-care definitions. The Illinois, Tennessee, and Virginia state health departments defined the not-in-care period as 12 months without evidence of care; the Virginia Department of Health defined not in care as evidence of care in 1 reference calendar year with no evidence of care in the following year (eg, evidence of care in 2014 but not in 2015).

The Louisiana Department of Health’s definition for not in care included people diagnosed with HIV infection within the past 12 months who had not entered into care 6-12 months after diagnosis and PWH (regardless of diagnosis date) who had not had a CD4 count or viral load taken in 12-36 months (definition used from October 1, 2013, through May 15, 2015). On May 16, 2015, the definition was updated to include PWH diagnosed with HIV infection within the past 9 months who had not entered into care 6-9 months after diagnosis and PWH (regardless of diagnosis date) who had not had a CD4 count or viral load taken in 9-36 months. In addition, Louisiana followed PWH who potentially had virologic failure (ie, 2 viral load test results >1000 copies/mL with no clinically significant decrease or a viral load >500 000 copies/mL with no subsequent test within 3 months).19

Steps in the Data to Care Process

Implementation of D2C programs required multiple activities in each step of the D2C process.

Step 1: PWH presumed to be not in care

The health departments generated listings of PWH presumed to meet the selection criteria from surveillance data and other sources. Illinois and Tennessee used their HIV surveillance database only, whereas Louisiana and Virginia combined their surveillance databases with other data sources, such as HIV laboratory data systems or partner services data systems. Louisiana updated its list weekly in an iterative automated process that also checked against its most recent referrals to identify which PWH were eligible for follow-up of linkage and reengagement activities.20 Virginia created a Care Markers Database by combining data from multiple sources (eg, Medicaid, electronic provider records, electronic laboratory reports, and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, among others) and used the database biannually to generate a list of PWH not in care.21,22 Tennessee generated its list annually, and Illinois generated its list monthly.23

Step 2: Verify data and prioritize PWH for follow-up

Every program cleaned data before determining eligibility for follow-up. Data cleaning included matching preliminary listings of PWH presumed to be not in care with other data sources to remove PWH who (1) had died, (2) had moved out of the jurisdiction, (3) were found to be in care, (4) were incarcerated, (5) were homeless (or were otherwise hard to reach), or (6) were currently under not-in-care investigation. The health departments used various data sources in this step, including databases for Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program services, the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, partner services, Medicaid, and health department patient services or billing systems. Information from ongoing not-in-care investigations or linkage efforts also informed data cleaning. Three jurisdictions used a commercially available people-search tool to obtain current contact information, such as addresses and telephone numbers. Health departments obtained additional contact information from other health databases (eg, sexually transmitted disease surveillance, partner services, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program services, Medicaid) or through publicly available online searches (eg, Google, tax records, obituaries, corrections listings).

When data-cleaning activities involved manipulating electronic data (ie, matching databases rather than manual look-up), having a master’s-level data analyst with experience in managing relational databases and statistical software on staff improved efficiency. Manual data cleaning could be performed by staff members with a college degree and some public health experience.

Each program prioritized PWH for follow-up in its own way. Because resources for D2C program specialists were limited, Tennessee prioritized not-in-care PWH living in geographic regions where D2C program specialists were assigned (ie, in regions with the highest incidence of HIV, which covered 80% of PWH not in care in the state). Louisiana prioritized PWH who had been out of care for a long time or whose last viral load was detectable. Illinois prioritized PWH living in regions that were not covered by previously funded HRSA or CDC HIV prevention and care projects. Virginia prioritized PWH living in health districts with the highest numbers of not-in-care PWH, with available specialists to conduct investigations, and where agencies had HIV services contracts with the Virginia Department of Health to perform follow-up.

Steps 3 and 4: Contact PWH and determine care status

After verifying, cleaning, and prioritizing the listings of not-in-care PWH, the health departments distributed the listings to linkage-to-care coordinators, disease intervention specialists, or other designated health department or partner agency staff members. Designated staff members attempted to contact PWH to confirm their care status as being in care or not in care and tracked the number of contact attempts. Some PWH were not contacted because the program determined they were deceased, out of jurisdiction, incarcerated, or for other reasons (eg, unable to locate).

Steps 5 and 6: Provide linkage or reengagement services and confirm engagement in care

In general, the linkage and reengagement process (Table 2) began with face-to-face or telephone contact with PWH. During the interviews, health department staff members assessed individuals’ needs for, and barriers to, accessing HIV medical care. Because PWH who had never received treatment or who had dropped out of HIV medical care often had multiple unmet needs (eg, food, housing, employment) and barriers to care (eg, transportation, health insurance, and behavioral health issues), they were offered referral or navigation services to meet these nonmedical needs before or while they were provided linkage to medical care. In all the D2C programs, staff members accompanied PWH to their initial medical appointments and offered assistance after the initial appointment. Follow-up data were captured in locally developed or existing systems modified for D2C purposes.

D2C programs reported similar definitions for linkage to and reengagement in care, which included keeping medical appointments (indicated mostly by laboratory markers, such as CD4 or viral load test results). However, the time between linkage-to-care attempts and case closeout ranged from 1.5 months in Illinois to 9 months in Tennessee; some D2C programs provided additional time as needed.

Linkage and reengagement staff members had various job titles (eg, surveillance-based service providers, linkage-to-care coordinators, and D2C specialists), education levels (eg, <college degree, college degree, or graduate degree), experience (eg, disease intervention, case management, nursing, social work, or patient navigation), and training (eg, risk-reduction counseling, treatment adherence).

Step 7: Enter information acquired into surveillance system

After completing linkage activities, program staff members entered new information obtained through D2C activities into the surveillance database to correct erroneous information (eg, PWH wrongly identified as not in care), increase data completeness, and improve overall program efficiency. All 4 D2C programs provided updated information to the HIV surveillance program, such as changes in names, dates of birth, current gender, telephone number, current address, vital status, transmission risk, test results, and incarceration status. Information about PWH’s awareness of their HIV status, whether they were taking antiretroviral therapy, and whether they wished to be contacted for HIV medical care engagement services was also shared. In Louisiana and Virginia, linkage or reengagement workers completed the Adult HIV Confidential Case Report Form or a similar form with new information and then submitted the forms either electronically or manually to the surveillance unit. Illinois developed an easily queried electronic system that expedited reporting, lessened the burden on D2C program and data management staff members, and improved the capacity to summarize the number of updated records.

Results

A total of 16 391 PWH (range, 1278-7048 per program) were initially presumed to be not in care by the 4 state health departments. Of 16 391 PWH presumed to be not in care, D2C programs excluded 2593 (15.8%) because they were being served under other grants or were not prioritized for CAPUS follow-up, which left 13 798 (84.2%) for follow-up (Figure 1; Table 3). Reviewing data on PWH and matching them to other available data led to the exclusion of 1054 (7.6%) PWH who were deceased or out of jurisdiction and 2892 (21.0%) PWH already in care. After exclusions, the D2C programs prioritized 9852 of 13 798 (71.4%) not-in-care PWH, or 9852 of 16 391 (60.1%) PWH initially presumed to be not in HIV care, for follow-up.

Figure 1.

Data to Care (D2C) process and overall outcomes among people with diagnosed HIV infection and not in HIV medical care, Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project, Illinois, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia state health departments, 2013-2016. D2C is a high-impact public health strategy that uses HIV surveillance and other data to identify people with diagnosed HIV infection who are in need of HIV medical care and other services and link them to those services.8 The CAPUS Demonstration Project was a 4-year cross-agency demonstration project funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.3 The time period covered was October 1, 2013, through September 29, 2016, for state health departments in Illinois, Louisiana, and Tennessee, and January 1, 2015, through September 29, 2016, for the Virginia Health Department.

Table 3.

Outcomes of the Data to Care (D2C)a program among people with diagnosed HIV infection who were not in HIV medical care, Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project,b 4 states, 2013-2016c

| Illinoisd | Louisiana | Tennessee | Virginia | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data to Care Steps | No. (%)e | No. (%)e | No. (%)e | No. (%)e | No. (%)e |

| Step 1. Identify PWH presumed to be not in care (denominator = Step 1A values) | |||||

| A. PWH initially identified as not in care | 5726 (100.0) | 7048 (100.0) | 2339 (100.0) | 1278 (100.0) | 16 391 (100.0) |

| B. PWH excludedf | 2341 (40.9) | 252 (3.6) | 0 | 0 | 2593 (15.8) |

| C. PWH included in CAPUS investigation | 3385 (59.1) | 6796 (96.4) | 2339 (100.0) | 1278 (100.0) | 13 798 (84.2) |

| Step 2. Verify data and prioritize PWH for follow-up (denominator = Step 1C values) | |||||

| A. Excluded because found to be in care after checks of other data systems | 998 (29.5) | 1789 (26.3) | 0 | 105 (8.2) | 2892 (21.0) |

| B. Excluded because of other reasons (eg, deceased, out of jurisdiction) | 445 (13.1) | 265 (3.9) | 0 | 344 (26.9) | 1054 (7.6) |

| C. PWH selected for contact or outreach by project/program staff members | 1942 (57.4) | 4742 (69.8) | 2339 (100.0) | 829 (64.9) | 9852 (71.4) |

| Step 3. Contact PWH (denominator = Step 2C values) | |||||

| A. Not contacted because deceased | 71 (3.7) | 129 (2.7) | 127 (5.4) | 9 (1.1) | 336 (3.4) |

| B. Not contacted because out of jurisdiction | 340 (17.5) | 287 (6.1) | 251 (10.7) | 26 (3.1) | 904 (9.2) |

| C. Not contacted because out of CAPUS area | 0 | 186 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 186 (1.9) |

| D. Not contacted because incarcerated | 9 (0.5) | 86 (1.8) | 24 (1.0) | 3 (0.4) | 122 (1.2) |

| E. Not contacted because of other reasons (eg, unable to contact) | 741 (38.2) | 337 (7.1) | 480 (20.5) | 47 (5.7) | 1605 (16.3) |

| F. Not contacted yet, but contact in progress | 132 (6.8) | 1809 (38.1) | 0 | 594 (71.7) | 2535 (25.7) |

| G. PWH contacted by project/program staff members | 649 (33.4) | 1908 (40.2) | 1457 (62.3) | 150 (18.1) | 4164 (42.3) |

| Step 4. Determine care status (denominator = Step 3G values) | |||||

| A. In careg | 407 (62.7) | 935 (49.0) | 1107 (76.0) | 137 (91.3) | 2586 (62.1) |

| B. Care status not yet determined | 99 (15.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99 (2.4) |

| C. PWH confirmed to be not in care | 143 (22.0) | 973 (51.0) | 350 (24.0) | 13 (8.7) | 1479 (35.5) |

| Step 5. Provide linkage or reengagement services (denominator = Step 4C values) | |||||

| A. Not yet offered linkage or reengagement services | 61 (42.7) | 0 | 20 (5.7) | 1 (7.7) | 82 (5.5) |

| B. Offered linkage or reengagement services but refused | 13 (9.1) | 440 (45.2) | 91 (26.0) | 3 (23.1) | 547 (37.0) |

| C. Offered linkage or reengagement services, but services not yet provided | 0 | 0 | 56 (16.0) | 0 | 56 (3.8) |

| D. PWH offered and provided linkage or reengagement services | 69 (48.3) | 533 (54.8) | 183 (52.3) | 9 (69.2) | 794 (53.7) |

| Step 6. Confirm engagement in care (denominator = Step 5D values) | |||||

| A. Confirmed not linked to HIV medical care within the predetermined timeg | 26 (37.7) | 37 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | 63 (7.9) |

| B. Linkage to HIV medical care not yet determined | 0 | 16 (3.0) | 20 (10.9) | 1 (11.1) | 37 (4.7) |

| C. PWH confirmed to be linked to HIV medical care | 43 (62.3) | 480 (90.1) | 163 (89.1) | 8 (88.9) | 694 (87.4) |

| Step 7. Enter information acquired into surveillance system | |||||

| A. Surveillance case records modified or updated because of D2C outreach activities | 662 | 470 | 1485 | 235 | 2852 |

Abbreviation: PWH, people with diagnosed HIV infection.

a D2C is a high-impact public health strategy that uses HIV surveillance and other data to identify PWH who are in need of HIV medical care and other services and link them to those services.8

b The CAPUS Demonstration Project was a 4-year cross-agency demonstration project funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.3

c The time period covered was October 1, 2013, through September 29, 2016, for state health departments in Illinois, Louisiana, and Tennessee, and January 1, 2015, through September 29, 2016, for the Virginia Department of Health.

d Does not include Chicago residents.

e Percentages within a step may not total to 100.0% because of rounding.

f Not prioritized for CAPUS follow-up or were served under other grants.

g Follow-up time varied from grantee to grantee.

The 4 state health departments successfully contacted 4164 of 9852 (42.3%) PWH selected for contact during the D2C program. Of the 9852 PWH whom staff members attempted to contact, 2535 (25.7%) were still being contacted at the end of the program period, 904 (9.2%) were out of jurisdiction, 336 (3.4%) were deceased, 122 (1.2%) were incarcerated, and 1605 (16.3%) were not contacted for other reasons (eg, unable to contact). Of 4164 PWH contacted, 1479 (35.5%) were not in care. Of the 1479 PWH confirmed as not in care, 794 (53.7%) were offered and provided linkage or reengagement services, 547 (37.0%) refused services, and 138 (9.3%) were in process and had not yet been offered or provided services by the end of the project period. The percentage of PWH confirmed linked to care was higher when calculated among PWH who accepted services (87.4%, 694 of 794) than among all PWH confirmed as not in care and contacted by program staff members (46.9%, 694 of 1479). A total of 2852 surveillance records were updated because of D2C program investigations.

In Louisiana, of 1559 PWH initially identified from surveillance data as being in care but having difficulty maintaining viral suppression, 962 (61.7%) were selected for follow-up (Figure 2). A total of 198 of 962 (20.6%) PWH were excluded because they had a viral load measure taken <90 days before the previous viral load measure, no longer had virologic failure, were deceased, or were out of jurisdiction. D2C program staff members successfully contacted 434 of 764 (56.8%) PWH selected for contact by the end of the reporting period to determine treatment adherence status. Of these 434 PWH, 165 (38.0%) were adhering to treatment or working on issues with their physician (self-reported), and 269 (62.0%) had a potential treatment adherence issue. Of the 269 PWH with potential treatment adherence issues, 153 (56.9%) were offered and provided adherence and support services, and 116 (43.1%) refused services. Overall, 104 of 153 (68.0%) PWH who accepted services were confirmed to have a substantially improved viral load (ie, a 3-fold decrease in viral load).

Figure 2.

Steps and outcomes of the Data to Care (D2C) process among people with diagnosed HIV infection (PWH) who had virologic failure, Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project, Louisiana Department of Health, 2012-2016. D2C is a high-impact public health strategy that uses HIV surveillance and other data to identify PWH who are in need of HIV medical care and other services and link them to those services.8 The CAPUS Demonstration Project was a 4-year cross-agency demonstration project funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).3 Virologic failure was defined as 2 consecutive viral load test results >1000 copies/mL at least 90-365 days apart in the past year with no clinically significant decrease between results (defined as a 3-fold decrease in viral load) or a viral load >500 000 copies/mL with no subsequent test within 3 months. PWH with an undetectable viral load within the past year and a subsequent viral load (taken at least 90 days later) that was >1000 copies/mL were excluded. This criterion was in place from October 1, 2013, through July 7, 2014, to exclude PWH who had minor changes in their viral load or other treatment-related issues unrelated to adherence. This D2C activity was implemented between October 1, 2013, and September 29, 2016, by the Louisiana Department of Health. A substantially improved viral load was defined as a 3-fold decrease in viral load. Data source: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents.19

Lessons Learned

CAPUS implementation identified gaps in data and set the groundwork for establishing new data-sharing processes, procedures, and partnerships to improve data quality. More complete laboratory reporting and updated data on vital status, address, risk behaviors, and other key information provided through the feedback process improved surveillance data in these jurisdictions. Data gaps might not have been identified and addressed if health departments had not implemented the D2C program. In addition, the feedback process created opportunities for increased communication, understanding of roles, and collaboration between prevention program and surveillance units.

The D2C program required intensive data verification, cleaning, and integration of information from various public health data sources to narrow the number of PWH eligible for contact, which eliminated a large proportion of PWH who were ineligible because they were deceased, out of jurisdiction or project area, or incarcerated. Cleaning data and creating iterative processes that incorporated information learned from investigations created new efficiencies.

Leveraging other data systems to supplement surveillance data was important. Two jurisdictions created systems that combined data from multiple health department programs to produce a better record of the HIV care status and contact information for PWH. Obtaining the current address for PWH was challenging, particularly for PWH who moved frequently. Integrating data sources to identify incarcerated PWH was also worthwhile. Other databases, such as partner services, Medicaid, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program services, and commercially available people-search databases, were useful for completing and updating contact information. Health departments found that communication with field staff members was key to identifying potential errors, assigning appropriate dispositions, and improving reports.

The Louisiana Department of Health implemented a promising D2C program that focused on identifying PWH who were not virally suppressed (ie, had virologic failure) and were in need of treatment adherence support services. Staff members had greater success contacting those PWH who were already in medical care than contacting PWH who were not in care. The program successfully provided services to PWH who had treatment adherence issues, which led to improvements in viral suppression for two-thirds of the PWH who were provided services. However, a large percentage of PWH contacted refused treatment adherence services. Some PWH refused services because they were switching medications or working with their physicians on adherence. The reasons for refusing adherence or linkage-to-care services should be further explored, because our data suggest that once PWH accept linkage and navigation services, they are typically linked to HIV medical care, and PWH who accept adherence support services may be more likely to reduce their viral load than PWH who refuse such services. Addressing unmet needs and barriers to care, such as transportation and housing, may be important to address before offering HIV medical care services.24-26 The small number of PWH who were offered but not yet provided linkage-to-care services suggests that linkage to care may be a long process for some PWH who have multiple needs.

Implementation challenges included staffing, providing timely linkage to services for PWH with multiple unmet needs, and navigating differences in the follow-up policies and procedures of facilities. Limitations in completeness of care status information in data systems also posed challenges to implementation. For example, 2 programs had difficulty in tracking the care status of PWH because data systems did not capture complete data on laboratory results or use of services. Staff member training; having dedicated D2C program staff members to bridge HIV prevention, care, and surveillance; and having other staff members assigned to data integration, cleaning, and quality assurance were important for implementation of D2C programs. Jurisdictions noted the benefits of having staff members in various positions (eg, disease intervention specialists, linkage personnel, case managers, and medical clinic staff members) working together. This collaboration resulted in better service delivery (eg, more timely referrals) and fostered better relationships between service providers and health department staff members.

Limitations

Our findings had several limitations. First, implementation practices varied across the 4 state health departments, which may have affected D2C program outcomes at each step of the D2C process. Each D2C program started at a different level of capacity in terms of staffing, resources, and data systems, and each program had unique implementation challenges, including data sharing, data system development, and prioritization of activities. In addition, the D2C program focusing on PWH with virologic failure who were in need of treatment adherence services was only implemented in one state. Therefore, differences in implementation could affect outcomes, and findings should be interpreted with caution. Second, data-reporting requirements were not set at the beginning of the project; as a result, data collection and categorization of investigation and linkage outcomes varied. Third, data included in this article did not include follow-up information for PWH who refused services or final outcomes for PWH who were not yet provided services by the end of the reporting period, which could affect interpretation of linkage and reengagement outcomes. Finally, delayed or incomplete reporting of laboratory information resulted in some PWH being initially categorized as not in care and later found to be in care. If they had been found to be in care sooner, these PWH would not have been included in the initial not-in-care lists. The availability and use of additional data sources for verification and cleaning varied by jurisdiction and may also have affected each program’s ability to update care status and other information in not-in-care lists.

Practice Implications

D2C is a proactive strategy that, when implemented as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention program, can help address disparities in access to HIV care, particularly among hard-to-reach communities that are underserved by health care systems. Future D2C programs should consider leveraging resources (eg, funding, relationships with care providers, information technology systems) and staff members to implement D2C programs. The D2C program provides important opportunities to work collaboratively with care providers and health care organizations to improve care outcomes. Care providers may benefit from obtaining viral suppression data on their patient population to gauge success of their patients’ care, as well as the linkage and reengagement assistance provided by health departments. In addition, D2C program activities may provide important opportunities to intervene when progress is stalled or viral suppression is not achieved or maintained. To be most efficient, D2C programs must improve data quality early in the process by integrating data-sharing and data-matching procedures to ensure current care status is known before generating not-in-care lists and contacting PWH. The number of deaths and the number of PWH in care revealed during these D2C program investigations suggest that surveillance programs need to assess the timeliness of current death ascertainment procedures and the completeness of laboratory reporting before implementing D2C programs.

D2C programs often required specific memoranda of understanding, data-sharing agreements, and supportive policies to conduct surveillance-based services. Agreements may be required between state and local health departments or within state health departments where care, prevention, and surveillance programs are not integrated. D2C programs should partner with correctional facilities to obtain data for matching purposes, because many incarcerated PWH appeared as not in care, and this population is not always eligible for follow-up. Asking PWH at the time of linkage if other services are needed, such as transportation or behavioral health support, and providing assistance in obtaining these services are likely to improve long-term retention in care.

CAPUS demonstrated progress toward national prevention goals by helping states improve health outcomes among PWH and laid important groundwork for data systems, protocols, and procedures for D2C programs. In particular, these lessons learned may be adapted by other health departments as they incorporate D2C program activities during the next 5 years as part of the flagship funding program to support HIV surveillance and prevention efforts under a new CDC funding opportunity announcement.27 Programmatic and research efforts are underway to identify additional models for D2C program collaborative processes and data sharing through the CDC and HRSA co-led Partnerships for Care project, and evaluation of linkage-to-care interventions and their cost effectiveness in the Cooperative Re-Engagement Controlled Trial (CoRECT) will also assist health departments as they implement their D2C programs.28,29 Our experience with CAPUS suggests that programs must address limitations in data systems to implement D2C programs efficiently. Additional research will be necessary to explore reasons for accepting or refusing services. Linking PWH to behavioral health and social services in addition to providing medical care may be important for PWH who face multiple barriers to care. Building on CAPUS, D2C program activities currently underway will further inform best practices.27-30

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Kim Williams (Prevention Research Branch [PRB]/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) and the contributions of the following people to the implementation of Data to Care activities reported in this article: Catherine Adelakun, Andrea Danner, Fangchao Ma, Annie McGowan, Jeremy Thomas, Alvey Walbert, Zhi Wang, Cheryl Ward, and Mildred Williamson, Illinois Department of Health; Mary Boutte, Althea Fryson, DeAnn Gruber, Heather Horton, and Valerie Thomas-White, Louisiana Department of Health; Kayla Burgess, Veronica Calvin, David Fields, Sabrina Gandy, Gabrielle Hamilton, Dana Hughes, Jalesa Sutton, Kimberly Truss, and Carolyn Wester, Tennessee Department of Health; Patrice Armstrong, Shaunda Bonner, Jan Hill, Debbie Isby, and Rosalind Knight, Shelby County (Tennessee) Health Department; Rochelle Roberts, Davidson County (Tennessee) Health Department; Susan Carr, Bryan Collins, Fatima Elamin, Diana Jordan, Elaine Martin, and Amanda Saia, Virginia Department of Health, and the rest of the Virginia Department of Health CAPUS team; William Adih (HIV Incidence and Case Surveillance Branch [HICSB]/CDC), Stephanie Celestain (Prevention Program Branch [PPB]/CDC), Nicole Crepaz (HICSB/CDC), Frank Ebagua (Capacity Building Branch [CBB]/CDC), George Hill (PPB/CDC), William Jeffries IV (PRB/CDC), Raekiela Taylor (PRB/CDC), Kim Thierry-English (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]), and Candace Webb (HIV/AIDS Bureau [HAB]/Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA]) from the CAPUS Federal Site Team in Illinois; William Bryant (HAB/HRSA), Ted Duncan (CBB/CDC), Kirk James (SAMHSA), Laura Kearns (PPB/CDC), Alexandra Oster (HICSB/CDC), Thomas Painter (PRB/CDC), and Lamont Scales (Office of Health Equity [OHE]/Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention [DHAP]/CDC) from the CAPUS Federal Site Team in Louisiana; Jonny Andia (CBB/CDC), Dwayne Banks (PPB/CDC), Wendy Briscoe (HAB/HRSA), Stacy Cohen (HICSB/CDC), Kristen Hess (HICSB/CDC), Cynthia Prather (PRB/CDC), Kim Thierry-English (SAMHSA), and Cheryl Williams (HICSB/CDC) from the CAPUS Federal Site Team in Tennessee; and Kim Brown (HAB/HRSA), Emilio German (OHE/DHAP/CDC), Kirk Henny (PRB/CDC), Laura Kearns (PPB/CDC), Benjamin Laffoon (HICSB/CDC), Ilze Ruditis (SAMHSA), Pilgrim Spikes (PRB/CDC), and David Whittier (CBB/CDC) from the CAPUS Federal Site Team in Virginia.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project was supported by the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund and led by CDC (PS12-1210). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

References

- 1. The White House. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/nhas-update.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2016. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2018;23(4):1–51. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-23-4.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) Demonstration Project. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/demonstration/capus/index.html. Published 2016. Accessed December 13, 2016.

- 4. Mulatu MS, Hoyte T, Williams KM, et al. Cross-site monitoring and evaluation of the Care and Prevention in the United States Demonstration Project, 2012-2016: selected process and short-term outcomes. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(suppl 2):87S–100S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sweeney P, Gardner LI, Buchacz K, et al. Shifting the paradigm: using HIV surveillance data as a foundation for improving HIV care and preventing HIV infection. Millbank Q. 2013;91(3):558–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evans D, Van Gorder D, Morin SF, Steward WT, Gaffney S, Charlebois ED. Acceptance of the use of HIV surveillance data for care engagement: national and local community perspectives. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(suppl 1):S31–S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wohl AR, Dierst-Davies R, Victoroff A, et al. Implementation and operational research: the Navigation Program: an intervention to reengage lost patients at 7 HIV clinics in Los Angeles County, 2012-2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(2):e44–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data to Care. 2018. https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/en/2018-design/data-to-care/group-1/data-to-care. Accessed September 28, 2018.

- 9. Tesoriero JM, Johnson BL, Hart-Malloy R, et al. Improving retention in HIV care through New York’s expanded partner services data-to-care pilot. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(3):255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buchacz K, Chen MJ, Parisi MK, et al. Using HIV surveillance registry data to re-link persons to care: the RSVP Project in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zetola NM, Bernstein K, Ahrens K, et al. Using surveillance data to monitor entry into care of newly diagnosed HIV-infected persons: San Francisco, 2006-2007. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2011. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2013;18(5):1–47. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/2011_Monitoring_HIV_Indicators_HSSR_FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohen SM, Gray KM, Ocfemia MC, Johnson AS, Hall HI. The status of the National HIV Surveillance System, United States, 2013. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(4):335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Advanced Systems Design, Inc. Patient Reporting Investigation Surveillance Manager (PRISM): Version 1.0. Tallahassee, FL: Advanced Systems Design, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. SAS Institute, Inc. SAS: Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Groupware Technologies, Inc. Provide Enterprise: Version 5.10. Wauwatosa, WI: Groupware Technologies, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CAPUS executive summary: Illinois Department of Public Health. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research/demonstration/capus/granteeillinois_web508c.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 18. Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau. CAREWare. 2018. https://hab.hrsa.gov/program-grants-management/careware. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 19. US Department of Health and Human Services, Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2017.

- 20. Brantley A, Fridge J, Burgess S, Bickham J. Expanding the use of surveillance data to improve HIV medical care engagement and viral suppression. Paper presented at: 2015 National HIV Prevention Conference; December 6-9, 2015; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ocampo JMF, Smart JC, Allston A, et al. Improving HIV surveillance data for public health action in Washington, DC: a novel multiorganizational data-sharing method. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(1):e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rhodes A, Yerkes L, Cadet J, Martin E. Virginia’s Care Marker Database: using multiple data sources for HIV care linkage and re-engagement. Paper presented at: 2015 National HIV Prevention Conference; December 6-9, 2015; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma F, McGowan A, Hicks C, Gates J, Ward C, Danner A. Linkage and re-engagement of HIV clients using HIV surveillance data in Illinois. Paper presented at: 2015 National HIV Prevention Conference; December 6-9, 2015; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pollini RA, Blanco E, Crump C, Zúñiga ML. A community-based study of barriers to HIV care initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(10):601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. US Department of Housing and Urban Development. HIV care continuum: the connection between housing and improved outcomes along the HIV care continuum. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/The-Connection-Between-Housing-and-Improved-Outcomes-Along-the-HIV-Care-Continuum.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed December 13, 2016.

- 26. Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 6):85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding opportunity announcement (FOA) PS18-1802: integrated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) surveillance and prevention programs for health departments. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/funding/announcements/ps18-1802/index.html. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Partnerships for Care (P4C): health departments and health centers collaborating to improve HIV health outcomes. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/demonstration/p4c/index.html. Published 2016. Accessed December 13, 2016.

- 29. FederalGrants.com. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Re-Engagement Controlled Trial (CoRECT). http://www.federalgrants.com/Centers-for-Disease-Control-and-Prevention-Cooperative-Re-Engagement-Controlled-Trial-CoRECT-63952.html. Published 2017. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Project PrIDE. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/demonstration/projectpride.html. Accessed December 13, 2016.