Abstract

Introduction:

The changes in the white blood cells counts and other blood parameters are well-recognized feature in sepsis. A ratio between neutrophils and lymphocytes can be used as a screening marker in sepsis. Even though new markers such as Procalcitonin and adrenomedullin have been rolled out in the field, implementation of these markers has been hindered by cost, accessibility, and proper validation. We looked for the ability of simple neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio (NLCR) when compared to the gold standard blood culture method in predicting bacteremia, on patients presented to emergency department (ED) with features of suspected community-acquired infections.

Materials and Methods:

A comparative study done on 258 adult patients, admitted with suspected features of community-acquired infections. The study group included all patients who had positive blood culture results on index presentation at ED. Patients with hematological, chronic liver and retroviral diseases, patients receiving chemotherapy, and steroid medications were excluded from the study. The study group was compared with gender- and age-matched control group who were also admitted with a suspicion of the same, but in whom the blood culture results were negative.

Results:

There was no statistically significant difference for predicting bacteremia by NLCR (>4.63) and culture positivity methods (P = 1.00). NLCR of > 4.63 predicts bacteremia with an accuracy of 84.9%.

Conclusion:

In our setting, NLCR performs equally well with culture positivity, in detecting severe infection at the early phase of disease. The NLCR may, therefore, be used as a suitable screening marker at ED for suspected community-acquired infections.

Keywords: Community-acquired bacteremia, C-reactive protein, neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio, septic shock, severe sepsis

INTRODUCTION

The changes in the white blood cells (WBCs) and other blood parameters are all well-recognized features in sepsis.[1] It has been already established that the WBC and neutrophils proliferate as a defense mechanism at the time of bacterial infection.[2,3,4] Bacteremia accounts for around 30% mortality in critically ill patients.[5] Early and prompt recognition of bacteremia are the key treatment. The traditional infectious markers such as WBC count, C-reactive protein (CRP) have got very little evidence in proving bacteremia in patients with community-acquired infections at the early stages.[6,7,8] Even though new markers such as procalcitonin and adrenomedullin have been rolled out in the field of infectious medicine, prompt implementation of these markers has been hindered by cost, accessibility, and proper validation. Lymphocytopenia as a response to systemic infection has been an already established concept by various authors.[9,10] Zahorec had already established a significant correlation between the disease severity and lymphocytopenia in an observational study conducted on septic patients in an oncologic Intensive Care Unit (ICU).[11] In a cohort study conducted in 21 patients by, Hawkins et al. have shown association between persistent T-cell and B-cell lymphocytopenia with Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteremia.[12] A ratio between neutrophils and lymphocytes (neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio [NLCR]) can be used as a prognostic factor in various disease conditions such as colorectal cancer, liver cancer, and appendicitis.[13,14]

NLCR was also found to have a significant correlation with the severity of disease and patient outcome according to acute physiology and chronic health evaluation 2 and sepsis-related organ failure assessment scores.[11,15,16] Now lymphocytopenia and NCLR are gaining interest in various disease conditions ranging from multiple infectious diseases to Cardiovascular diseases.

We looked for the ability of these parameters when compared to the traditional infection markers in predicting bacteremia, on patients presented to emergency department (ED) with features of SIRS and suspected features of community-acquired infections. Thus, this can be a cheap and reliable marker for predicting bacteremia and early targeted treatment can be initiated at the earliest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An institutional and ethical committee approval was taken to conduct this retrospective comparative study on 258 consecutive adult patients (18 years or older), who were admitted to Emergency Medicine Department over a 12 months period (September 2015– September 2016) with suspected community-acquired infections. Patients were admitted to Amrita Institute of Medical Science whose annual Emergency Medicine Department census is approximately 30,000 patients per year. Based on an average observed in an early publication with 95% confidence interval (CI) level and 90% power, a minimum sample size comes to 67. This has been calculated using N master software. The objective of the study is to assess the viability of NLCR as predictive marker of bacteremia in ED.

In our study group, we included all the patients with suspected community-acquired infections, meeting the SIRS criteria and in whom the blood culture and sensitivity results obtained are positive on presentation at emergency Medicine Department.

SIRS was defined as the occurrence of at least two of the following criteria:

Fever >38.0°C or hypothermia <36.0°C, tachypnea >20 breaths/min, tachycardia > 90 beats/min, leukocytosis >12 × 109 cells/L, or leukopenia <4 × 109 cells/L. Bacteremia was defined as a positive blood culture result.

Patients with hematological, chronic liver and retroviral diseases, patients receiving chemotherapy medications, and patients receiving glucocorticoids medications were excluded from the study. The study group was compared with age- and gender-matched control group who was also admitted with a suspicion of community-acquired infections but in whom the blood culture results came as negative. Same time drawn blood sample was used for comparing the variables. Statistical analysis in our study was done using IBM-SPSS version 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Categorical variables are expressed by frequency and percentage. Numerical variables are presented using mean and standard deviation. To find the statistical significance of numerical variables between culture positive and culture negative group, Sample t-test and Mann – Whitney U test – For non parametric data was used. To find the comparability of sex between two groups, Chi-square test was used.

RESULTS

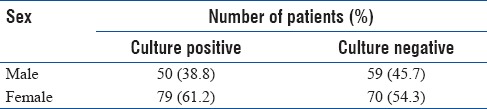

There were 258 patients analyzed who were meeting the inclusion criteria. After necessary exclusions were made, 129 patients came positive for various organisms in the blood drawn and sent for culture and sensitivity from ED. This study group were compared with 129 other patients who were also admitted with suspected community acquired infections, but in whom the blood culture reports were negative. There were 129 subjects in both study and control groups within the age range of 18–90 years. Sex distribution of both the groups is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sex distribution among culture positive and negative group

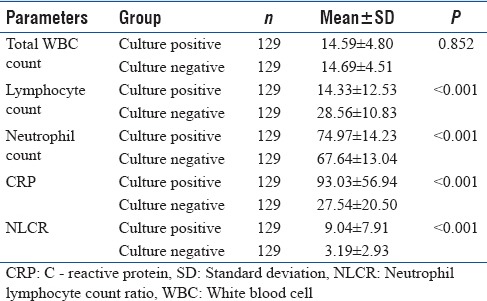

Majority of the isolates cultured from the study group were Gram-negative bacilli (58.9%), followed by Gram-positive cocci (34.9%), fungi (5.4%), and Gram-negative cocci (0.8%). Infectious markers on presentation to the emergency medicine department for the study group and the control group are shown in the Table 2. The WBC count in the study group did not differ significantly from that of the control group (14.59 ± 4.80 vs. 14.69 ± 4.51 * 109/L; CI– 95%; P = 0.852). The total WBC count <4× 109/L or >12 × 109/L is used in defining systemic inflammatory response syndrome according to the standard definition.[17] There was a significant difference in the neutrophil count of the study group when compared to that of the control group (74.96 ± 14.23 vs. 67.64 ± 13.04 * 109/L; CI– 95%; P < 0.001). The lymphocyte count of the study group varied significantly when compared to the control group (14.33 ± 12.53 vs. 28.56 ± 10.83 * 109/L; CI– 95%; P < 0.001). The CRP of the study group was significantly higher when compared to the control group (93.03 ± 56.94 vs. 27.54 ± 20.50 * 109/L; CI– 95%; P < 0.001). There was a significant difference in NLCR of the study group when compared to the control group (9.04 ± 7.91 vs. 3.91 ± 2.93; CI– 95%; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of various parameters

The mean value of infection markers such as total count, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and CRP for culture-positive group was 14.59 ± 4.80, 14.33 ± 12.53, 74.97 ± 14.23, and 93.03 ± 56.94, respectively. Similarly, in culture-negative group, the mean value of infection markers was such as total count, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and CRP was 14.69 ± 4.51, 28.56 ± 10.83, 67.64 ± 13.04 and 27.54 ± 20.50, respectively.

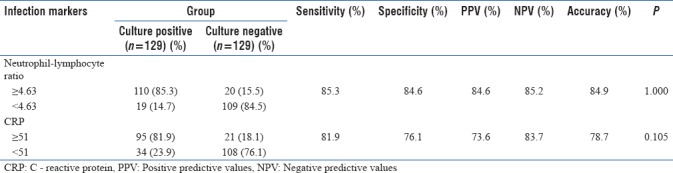

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy for CRP was 81.9%, 76.1%, 73.6%, 83.7%, and 78.7%, respectively, which was less when compared to that of N/L ratio; for which sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy was 85.3%, 84.6%, 84.6%, 85.2%, and 84.9%, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, negative predictive values, and accuracy for C - reactive protein and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in predicting bacteremia

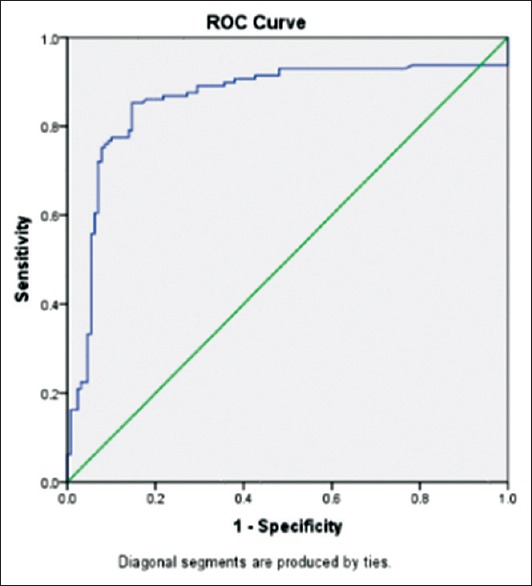

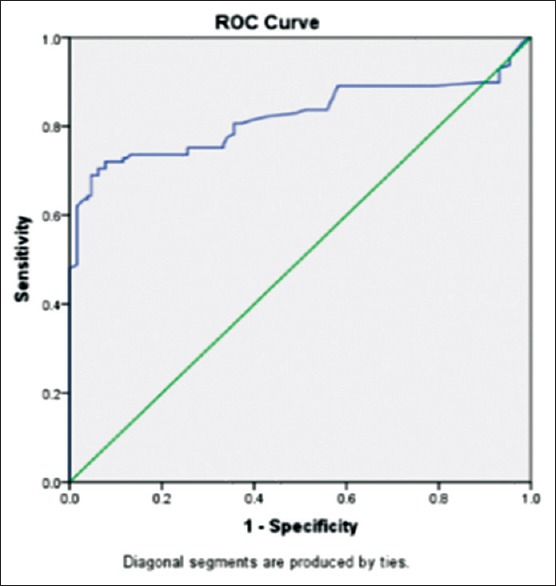

The ROC curve of two infectious markers, i.e., CRP and NLCR for culture positive and culture negative group is shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) for CRP level was 0.821 with CI between 0.765 and 0.877 whereas for NLCR was 0.859 with CI between 0.808 and 0.911. The AUC of NLCR differed significantly from that for CRP hence proving that NLCR correlates better in predicting bacteremia.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating curve of C-reactive protein for differentiating bacteraemia

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curve for neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio for differentiating bacteremia

Discussions

Blood culturing method is the considered as the gold standard investigation of choice in confirming bacterial infection. However, the factors such as time consumption, chances of contaminates, previous usage of antibiotics, etc., can put this investigation modality down the list when it comes to the modern emergency medicine practise.[18,19] Conventionally used infection markers, such as CRP levels, WBC counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels have got poor discriminating capacity for differentiating bacterial versus nonbacterial infections.[6,7,8] Lymphocytopenia was a marked feature in severe sepsis but did not gain wide acceptance as a definitive infection marker. The mechanisms for this marked depletion in lymphocyte counts accounts to margination, redistribution of lymphocytes in the lymphatic system, and marked apoptosis in cases of septic shock.[20,21] It has been already established that cell apoptosis is strongly associated with sepsis.[22] A prospective study conducted by Zahorec observed lymphocytopenia in patients admitted with severe sepsis and septic shock.[11] Similarly, in a study done by Wyllie et al. demonstrated the advantages of using lymphocytopenia in predicting bacteremia in adult patients with sepsis. Later, he also demonstrated that CRP done alone is not useful in predicting bacteremia, unless compiled with lymphocytopenia or neutrophilia.[8,11] On a multivariate study, lymphocytopenia was strongly associated with bacteremia.[9] We also found that in our study group there was profound neutrophilia when compared to the control group. It has been already established in various studies that there will neutrophil upregulation in severe sepsis and septic shock.[9] In our study, the samples were taken within 1 h of presentation to ED and compared with other parameters which has also been take simultaneously thus avoided the chances of hospital acquired infection hindering the data. In addition, we compared the study group with gender- and age-matched control group, as lymphocyte count may decline as the age advances.[23] There are upcoming evidence on NLCR as a predictive factor in various clinical settings. The use of NLCR in prognosticating disease has been already demonstrated in various clinical conditions such as lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and patients with hepatocellular cancer. The NLCR is an important parameter in predicting bacteremia in suspected community-acquired infections. Zahorec has demonstrated that NLCR can be a marker of severity in septic patients admitted to an oncology ICU.[11] Cornelis PC de Jager has demonstrated that NLCR is superior to the traditional infection markers such as CRP in predicting bacteremia at an ED.[10] In our setting, we have observed that NLCR can be used as screening marker in predicting bacteremia. Its easy access and cost factor can be a boon for both medical professionals and especially for the patients.

We have observed that the specificity, sensitivity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of NLCR was highest when compared with other traditional infections markers. Hence, NLCR proves to be a simple and easily accessible marker in screening patients with suspected community-acquired infections for bacteremia.

CONCLUSION

The ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte count can be used in predicting bacteremia for suspected community-acquired infections at ED. Since it has shown a good accuracy in predicting bacteremia it can be added to the day to day practice of an ED physician while dealing with critically ill patients suspected with community-acquired infections. As this method is simple, cost-effective and easily assessed, it can be used in giving optimized care for the patients.

Limitations

As this is a retrospective comparative study, the reliability of NLCR for predicting bacteremia should be evaluated on a prospective basis

The nutritional factor as a cause of lymphocytopenia has not been considered as an excluding factor

The perseverance to the hospital protocols in techniques of blood sampling for culture method has not been evaluated since this can cause errors in culture results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bone RC, Sibbald WJ, Sprung CL. The ACCP-SCCM consensus conference on sepsis and organ failure. Chest. 1992;101:1481–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Wright SB, Moore R, Bates DW. Who needs a blood culture? A prospectively derived and validated clinical prediction rule. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:435–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gombos MM, Bienkowski RS, Gochman RF, Billett HH. The absolute neutrophil count: Is it the best indicator for occult bacteremia in infants? Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109:221–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaacman DJ, Shults J, Gross TK, Davis PH, Harper M. Predictors of bacteremia in febrile children 3 to 36 months of age. Pediatrics. 2000;106:977–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leibovici L, Greenshtain S, Cohen O, Mor F, Wysenbeek AJ. Bacteremia in febrile patients. A clinical model for diagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1801–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro MF, Greenfield S. The complete blood count and leukocyte differential count. An approach to their rational application. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:65–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-1-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seebach JD, Morant R, Rüegg R, Seifert B, Fehr J. The diagnostic value of the neutrophil left shift in predicting inflammatory and infectious disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:582–91. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/107.5.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyllie DH, Bowler IC, Peto TE. Bacteraemia prediction in emergency medical admissions: Role of C reactive protein. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:352–6. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.022293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyllie DH, Bowler IC, Peto TE. Relation between lymphopenia and bacteraemia in UK adults with medical emergencies. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:950–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.017335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jager CP, van Wijk PT, Mathoera RB, de Jongh-Leuvenink J, van der Poll T, Wever PC, et al. Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Crit Care. 2010;14:R192. doi: 10.1186/cc9309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts – rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001;102:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins CA, Collignon P, Adams DN, Bowden FJ, Cook MC. Profound lymphopenia and bacteraemia. Intern Med J. 2006;36:385–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman DA, Goodman CB, Monk JS. Use of the neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Am Surg. 1995;61:257–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:181–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mare TA, Treacher DF, Shankar-Hari M, Beale R, Lewis SM, Chambers DJ, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic significance of monitoring blood levels of immature neutrophils in patients with systemic inflammation. Crit Care. 2015;19:57. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0778-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuutila J, Lilius EM. Distinction between bacterial and viral infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:304–10. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3280964db4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutfiyya MN, Henley E, Chang LF, Reyburn SW. Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:442–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala A, Herdon CD, Lehman DL, Ayala CA, Chaudry IH. Differential induction of apoptosis in lymphoid tissues during sepsis: Variation in onset, frequency, and the nature of the mediators. Blood. 1996;87:4261–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, et al. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi VD, Kalvakolanu DV, Cross AS. Simultaneous activation of apoptosis and inflammation in pathogenesis of septic shock: A hypothesis. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:180–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNerlan SE, Alexander HD, Rea IM. Age-related reference intervals for lymphocyte subsets in whole blood of healthy individuals. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1999;59:89–92. doi: 10.1080/00365519950185805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]