Abstract

Objective

We previously reported that the largest diameter of retrieved lymph nodes (LNs) correlates with the number of LNs and is a prognostic factor in stage II colon cancer. We examine whether T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells in LNs are related to the number of LNs and survival.

Methods

The subjects comprised 320 patients with stage II colon cancer. An LN with the largest diameter was selected in each patient. The positive area ratios of cells that stained for CD3 and CD20, and the numbers of CD56-positive cells were measured.

Results

The CD3-positive area ratio was 0.39 ± 0.08 and CD20-positive area ratio was 0.42 ± 0.10. The mean number of CD56-positive cells was 19.3 ± 22.7. The area ratios of B cells and T cells and the number of NK cells were significantly related to the sizes of the largest diameter LNs. The number of NK cells significantly correlated with the number of LNs and was an independent prognostic factor. On multivariate analysis, pathological T stage (T4 or T3; HR 4.71; p < 0.001) and the number of CD56-positive cells (high or low; HR 0.22; p < 0.001) were found to be independent prognostic factors.

Conclusions

The number of NK cells in the largest diameter LNs can most likely be used as a predictor of recurrence.

Keywords: Colonic neoplasm, Adenocarcinoma, Natural killer cells, Lymph nodes, Survival analysis

Introduction

In patients with stage II or III colon cancer, the retrieval of high numbers of lymph nodes (LN) has been reported to be associated with good outcomes [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Factors such as stage migration [9, 10, 11, 12] and the immune response of the host to tumors (tumor-host interactions) have been proposed as underlying reasons [5, 6, 13, 14, 15] but remain to be established. The incidence of understaging was estimated to be only 2–5% [16] and thus cannot explain why the number of retrieved LNs is a prognostic factor.

The relations between the number of retrieved LNs and tumor-host interactions remain controversial. Several studies have reported that lymph-node size may correlate with the number of retrieved LNs [16, 17]. We previously reported that a greater maximum long-axis diameter of retrieved LNs is associated with the retrieval of more LNs and better outcomes [18].

The size of LNs with no metastasis may reflect the state of immune reactions in the LNs [5, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22]. We therefore hypothesized that patients with a strong immune response have large LNs and many retrieved LNs.

LNs can be divided into 3 regions (the cortex, paracortex, and medulla) and consist mainly of T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. The aim of our study was to examine whether T cells, B cells, and NK cells in the largest diameter LNs are related to lymph-node size and the number of retrieved LNs and to determine whether these factors can be used to predict outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The study group comprised 320 consecutive patients with pathological stage II colon cancer who underwent elective radical surgery in Tokai University Hospital from January 1991 through December 2003. Patients who underwent emergency surgery were excluded from the study. This is a retrospective chart review of a prospectively maintained database.

Surgery

All operations were performed by 4 or 5 staff members, consisting of 2 or 3 surgeons (S.S., T.S., A.T., K.O., or G.S.) and 1 or 2 members of the surgical team. All operations were performed with an open approach. No patient underwent laparoscopic surgery. For lymph-node dissection, all pericolic nodes, intermediate nodes, and main nodes were dissected [23]. Lymph-node dissection was extended to the bifurcation of the ileocolic artery, right colic artery, or both from the superior mesenteric artery in patients with right-sided colon cancer, the bifurcation of the middle colic artery from the superior mesenteric artery in patients with transverse colon cancer, and the bifurcation of the inferior mesenteric artery from the aorta in patients with left-sided colon cancer. Both the distal and proximal resection margins were at least 7 cm from the tumor margin.

Pathological Procedures

One of the members of the colorectal surgical team dissected the resected specimens in the operation room within 30 min after excision. LNs were identified by direct inspection and manual palpation after closely slicing the mesocolon. Fat clearance methods were not used in any patient. Pathologists examined all specimens considered to be candidates for LNs. LNs fixed in formalin were thinly sliced to obtain maximal cut surfaces and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Largest Diameter LNs and Immunohistochemical Staining

In hematoxylin and eosin-stained specimens, an LN with the greatest long-axis diameter was selected in each patient and was designated as the largest diameter LN. Immunohistochemical staining was performed with the use of CD3 as a T-cell marker, CD20 as a B-cell marker, and CD56 as an NK-cell marker by automated immunohistochemical procedure (Dako Autostainer, Dako Co., Ltd., Glostrup, Denmark).

The expressions of CD3, CD20, and CD56 were evaluated by immunohistochemical staining (indirect method), using CD3 Rabbit-Mono (SP7; Nichirei Biosciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at a 1: 150 dilution, CD20cy (DAKO Co., Ltd., Glostrup, Denmark) at a 1: 200 dilution, and Liquid Mouse Monoclonal Antibody CD56 (NCAM; Leica Biosystems Newcastle Ltd., Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom) at a 1: 100 dilution as the primary antibodies respectively.

Evaluation of T Cells, B Cells, and NK Cells in the Largest Diameter LNs

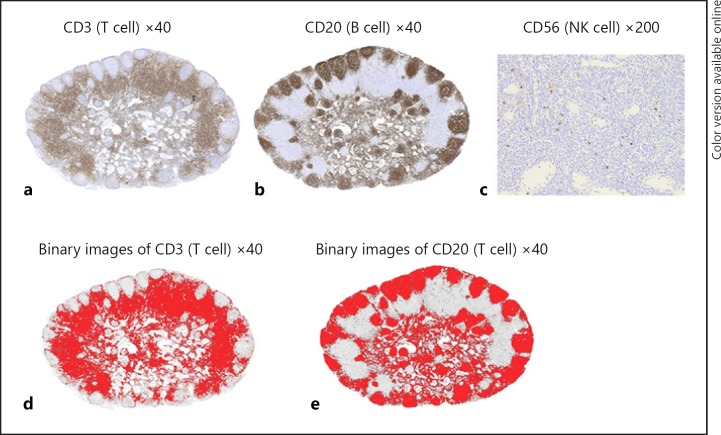

The long-axis diameters and areas of LNs, CD3-positive areas, and CD20-positive areas were measured with the use of a computer digitizer (Adobe Photoshop CS5®, ImageJ 1.47). The digitized images (Fig. 1a, b) were converted from RGB images into 8-bit images. The threshold was set at 18–180 for CD3 and 18 to 145 for CD20, and binarization processing was performed (Fig. 1d, e). The red areas of the created binary images were measured. The CD3- and CD20-positive area ratios were calculated by dividing the CD3-positive area and the CD20-positive area by the area of each LN. Because CD 56-positive cells are scattered in LNs (Fig. 1c), the number of CD56-positive cells was determined by selecting 4 regions that showed accumulations of CD56-positive cells at a magnification of 200y. The number of CD56-positive cells was counted in a tally counter. The mean value of CD56-positive cells per site (0.39 mm2) was calculated.

Fig. 1.

Representative largest diameter lymph nodes (LN) stained with CD3 (a), CD20 (b), CD56 (c). Because regions of the LNs were stained by CD3 and CD20, the area ratios of the stained regions in the LNs were evaluated. Because CD56-positive cells were scattered in the LNs, the number of CD56-positive cells was evaluated. Binary images after thresholding were shown in d and e.

Statistical Analyses

To examine clinicopathological factors related to the number of retrieved LNs and the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, the patients were divided into 2 groups according to the median values obtained for the number of retrieved LNs, the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, the CD3-positive area ratio, the CD20-positive area ratio, and the number of CD56-positive cells. The data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the relations between continuous variables.

In survival analysis, recurrence-free interval was regarded as a variable. Cumulative survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate analysis was performed using log-rank tests. Multivariate analysis was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. In the survival analysis, the cutoff values for continuous variables were calculated from the receiver operating characteristic curves for recurrence or death from the primary cancer on the basis of an age of 65 years, the number of retrieved LNs, the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, the CD3-positive area ratio, the CD20-positive area ratio, and the number of CD56-positive cells. p values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate significant difference. Statistical calculations were performed using JMP version 13 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our university (08R-032).

Results

Patients' Characteristics

The patients' characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The right side of the colon included the cecum, the ascending colon, and the transverse colon. The left side of the colon included the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the rectosigmoid colon. At the discretion of the patients and their attending physicians, postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was received by 145 patients (45%). The adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimens consisted of oral fluoropyrimidine or intravenous 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin. The median number of retrieved LNs was 12.

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics (n = 320)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 197 (62) |

| Female | 123 (38) |

| Age, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 64.8±12.2 |

| Quartiles | 57, 66, 74 |

| Location of the tumor | |

| Right colon | 128 (40) |

| Left colon | 192 (60) |

| Pathological T stage* | |

| T3 | 263 (82) |

| T4 | 57 (18) |

| Histological type† | |

| G1 | 185 (58) |

| G2 | 116 (36) |

| G3 | 19 (6) |

| Lymphatic invasion | |

| Positive | 261 (82) |

| Negative | 59 (18) |

| Venous invasion | |

| Positive | 226 (71) |

| Negative | 94 (29) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 145 (45) |

| No | 175 (55) |

| Number of retrieved lymph nodes | |

| Mean ± SD | 14.8±10.1 |

| Quartiles | 8.0, 12.0, 20.0 |

International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 7th ed.

Histologic grade: G1, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma; G2, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; G3, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Locations of the largest diameter LNs and the CD3-positive area ratios, CD20-positive area ratios, and the number of CD56-positive cells in the largest diameter LNs are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The locations of the largest diameter LNs and measurements of the size of the largest diameter LNs, CD3- and CD20-positive areas and area ratios, and the number of NK cells in the largest diameter LNs (n = 320)

| Locations of the largest diameter LNs | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Paracolic LNs | 157 (49) | |

| Intermediate LNs | 109 (34) | |

| Main LNs | 54 (17) |

| Measurements of the largest diameter LNs | Mean ± SD | Quartiles |

|---|---|---|

| Long axis, mm | 8.9±3.7 | 6.2, 8.3, 11.1 |

| Area, mm2 | 41.0±31.4 | 18.1, 33.8, 55.6 |

| CD3-positive area, mm2 | 16.1±12.6 | 7.2, 12.8, 21.2 |

| CD3-positive area ratio | 0.39±0.08 | 0.35, 0.39, 0.44 |

| CD20-positive area, mm2 | 17.5±14.7 | 7.0, 13.2, 23.3 |

| CD20-positive area ratio | 0.42±0.10 | 0.35, 0.43, 0.49 |

| Number of CD56-positive cells, 0.39 mm2 | 19.3±22.7 | 6.8, 14.4, 25.6 |

The largest diameter LNs were located in the pericolic LNs or the intermediate LNs in 83% of the patients and were located in the main LNs in 17% of the patients. CD3-positive cells were seen in the paracortex; CD20-positive cells were seen in lymphatic follicles in the cortex and CD56-positive cells were seen in the paracortex and the regions other than the lymphatic follicles in the cortex. The median long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs was 8.3 mm. The median CD3-positive area ratio and CD20-positive area ratio were 0.39 and 0.43 respectively. The median number of CD56-positive cells was 14. The standard deviations of the CD3-positive area ratio and the CD20-positive area ratio were 0.08 and 0.10, respectively, indicating small variability. No CD56-positive cells were found in only 2 patients (0.6%). The standard deviation of the number of CD56-positive cells was 22.7, indicating large variability.

Clinicopathological factors, the number of retrieved LNs, and the long-axis diameters of the largest diameter LNs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinicopathological factors related to the number of retrieved LNs and the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs

| n (%) | Number of retrieved LNs | p value | Long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, mm | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 197 (62) | 14.5±10.1a | 0.501b | 8.6±3.5a | 0.040b |

| Female | 123 (38) | 15.3±10.3 | 9.5±3.9 | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| <65 | 138 (43) | 16.8±10.5 | <0.001b | 9.6±3.5 | 0.001b |

| ≥65 | 182 (57) | 13.4±9.6 | 8.4±3.7 | ||

| Location of the tumor | |||||

| Right colon | 128 (40) | 18.3±11.3 | <0.001b | 10.2±3.9 | <0.001b |

| Left colon | 192 (60) | 12.5±8.5 | 8.1±3.2 | ||

| Pathological T stage* | |||||

| ≥T3 | 263 (82) | 14.8±10.0 | 0.855b | 8.9±3.5 | 0.759b |

| T4 | 57 (18) | 14.9±11.0 | 9.2±4.2 | ||

| Histological type† | |||||

| G1 | 185 (58) | 14.5±10.2 | 0.542c | 9.1±3.7 | 0.273c |

| G2 | 116 (36) | 15.4±10.5 | 8.5±3.7 | ||

| G3 | 19 (6) | 15.1±7.6 | 9.7±3.6 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | |||||

| Positive | 261 (82) | 14.5±10.0 | 0.228b | 8.8±3.6 | 0.075b |

| Negative | 59 (18) | 16.2±10.9 | 9.7±3.7 | ||

| Venous invasion | |||||

| Positive | 226 (71) | 14.3±9.4 | 0.322b | 8.9±3.6 | 0.783b |

| Negative | 94 (29) | 16.2±11.6 | 9.0±3.8 | ||

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||

| Yes | 145 (45) | 14.5±9.8 | 0.781b | 9.1±3.8 | 0.556b |

| No | 175 (55) | 15.1±10.5 | 8.7±3.6 | ||

| Number of retrieved LNs | |||||

| <12 | 149 (47) | – | 7.0±2.9 | <0.001b | |

| ≥12 | 171 (53) | – | 10.6±3.5 | ||

| Long axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, mm | |||||

| <8.3 | 159 (50) | 10.0±6.2 | <0.001b | – | |

| ≥8.3 | 161 (50) | 20.0±11.0 | – | ||

| CD3-positive area ratio | |||||

| <0.39 | 163 (51) | 15.1±9.4 | 0.199b | 9.4±3.5 | 0.006b |

| ≥0.39 | 157 (49) | 14.6±10.9 | 8.4±3.7 | ||

| CD20-positive area ratio | |||||

| <0.43 | 160 (50) | 14.5±9.1 | 0.739b | 8.4±3.6 | 0.022b |

| ≥0.43 | 160 (50) | 15.1±11.1 | 9.4±3.7 | ||

| Number of CD56-positive cells, 0.39 mm2 | |||||

| <14 | 159 (50) | 12.6±8.8 | <0.001b | 8.1±3.2 | 0.001b |

| ≥14 | 161 (50) | 17.0±10.9 | 9.7±3.9 | ||

International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 7th ed.

Histologic grade: G1, well differentiated adenocarcinoma; G2, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; G3, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Mean ± SD.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Kruskal-Wallis test. LN, lymph node.

Age younger than 65 years and tumor location on the right side of the colon were factors that were significantly related to higher numbers of retrieved LNs. The number of retrieved LNs was significantly greater in patients with a long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs of ≥8.3 mm than in patients with a long-axis diameter of < 8.3 mm. The number of retrieved LNs was significantly higher in patients with ≥14 CD56-positive cells than in patients those with < 14 CD56-positive cells.

Female sex, an age of younger than 65 years, tumor location on the right side of the colon, and the retrieval of 12 or more LNs were all related to a significantly greater long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs. A CD3-positive area ratio of < 0.39, a CD20 positive area ratio of ≥0.43, and ≥14 CD56-positive cells were associated with a significantly greater long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs. Age, tumor location, and the number of CD56-positive cells were related to both the number of retrieved LNs and the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs.

Survival Analysis (Table 4)

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate cox proportional hazard models of recurrence-free interval

| Characteristic | n (%) | 5 Years RFI rate†, % | Univariate p value†† | Multivariable Cox model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 197 (62) | 82 | 0.676 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Women | 123 (38) | 82 | 1.01 | 0.57–1.74 | 0.983 | |

| Age, year | ||||||

| <65 | 138 (43) | 84 | 0.494 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| ≥65 | 182 (57) | 81 | 1.26 | 0.70–2.30 | 0.444 | |

| Location of the tumor | ||||||

| Right colon | 128 (40) | 85 | 0.717 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Left colon | 192 (60) | 81 | 0.94 | 0.53–1.67 | 0.819 | |

| Pathological T stage* | ||||||

| T3 | 263 (82) | 88 | <0.001 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| T4 | 57 (18) | 54 | 4.71 | 2.64–8.37 | <0.001 | |

| Histological type† | ||||||

| G1 | 185 (58) | 82 | 0.541 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| G2 | 116 (36) | 84 | 0.73 | 0.39–1.31 | 0.300 | |

| G3 | 19 (6) | 78 | 1.44 | 0.49–3.44 | 0.476 | |

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||||

| Positive | 261 (82) | 82 | 0.532 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Negative | 59 (18) | 84 | 0.78 | 0.34–1.62 | 0.521 | |

| Venous invasion | ||||||

| Positive | 226 (71) | 80 | 0.134 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Negative | 94 (29) | 88 | 0.87 | 0.42–1.69 | 0.692 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 145 (45) | 84 | 0.417 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| No | 175 (55) | 81 | 1.06 | 0.60–1.88 | 0.839 | |

| Number of retrieved lymph nodes | ||||||

| <10 | 112 (35) | 76 | 0.039 | – | – | – |

| ≥10 | 208 (65) | 86 | – | – | – | |

| Long axis diameter of the largest diameter lymph nodes, mm | ||||||

| <5.2 | 44 (14) | 67 | 0.004 | – | – | – |

| ≥5.2 | 276 (86) | 85 | – | – | – | |

| CD3-positive area ratio | ||||||

| <0.34 | 70 (22) | 73 | 0.021 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| ≥0.34 | 250 (78) | 85 | 0.73 | 0.40–1.36 | 0.309 | |

| CD20-positive area ratio | ||||||

| <0.33 | 61 (19) | 93 | 0.023 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| ≥0.33 | 259 (81) | 80 | 2.17 | 0.86–7.27 | 0.107 | |

| Number of CD56-positive cells, 0.39 mm2 | ||||||

| <27 | 245 (77) | 79 | 0.003 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| ≥27 | 75 (23) | 94 | 0.22 | 0.07–0.56 | <0.001 | |

International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors 7th ed.

Histologic grade: G1, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma; G2, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; G3, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Kaplan-Meier method.

log-rank test.

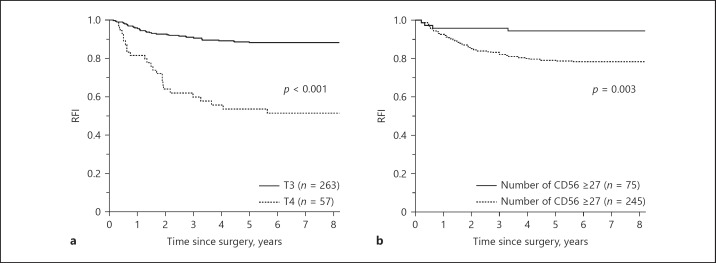

The median follow-up period of the patients who survived without recurrence was 118 months. Recurrence occurred in 56 patients (18%). Overall, 110 patients (34%) died of all causes and 47 patients (15%) died of the primary cancer. The cutoff values calculated from the receiver operating characteristic curves were 10 for the number of retrieved LNs, 5.2 mm for the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, 0.34 for the CD3-positive area ratio, 0.33 for the CD20-positive area ratio, and 27 for the number of CD56-positive cells. On univariate analysis, pathological T3 stage, number of retrieved LNs ≥10, long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LN ≥5.2 mm, CD3-positive area ratio ≥0.34, CD20-positive area ratio < 0.33, and the number of CD56-positive cells ≥27 were significantly related to better outcomes. Before multivariate analysis, the number of retrieved LNs and the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs were excluded from the analysis to avoid multicollinearity because these variables are related to other covariants. Multivariate analysis showed that pathological T stage and the number of CD56-positive cells were independent prognostic factors. The 57 patients (18%) with pathological T4 stage had significantly poorer outcomes than the 263 patients (82%) with pathological T3 stage (Fig. 2a), and the 75 patients (23%) with the number of CD56-positive cells ≥27 had significantly better outcomes than the 245 patients (77%) with the number of CD56-positive cells < 27 (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Recurrence free interval (RFI). Differences in RFI were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate a significant difference. a Comparison of RFI according to pathological T stage. b Comparison of RFI according to the number of CD56-positive cells.

Relations of the number of CD56-positive cells in the largest diameter LNs to the number of retrieved LNs and the long-axis diameter, CD3-positive area, CD3-positive area ratio, CD20-positive area, and CD20-positive area ratio were shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Relations of the number of CD56-positive cells in the largest diameter LNs to the number of retrieved LNs and the long-axis diameter, CD3-positive area, CD3-positive area ratio, CD20-positive area, and CD20-positive area ratio

| Number of CD56-positive cells |

||

|---|---|---|

| ρ* | p value | |

| Number of retrieved LNs | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Long axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| CD3-positive area, mm2 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| CD3-positive area ratio | −0.04 | 0.529 |

| CD20-positive area, mm2 | 0.16 | 0.004 |

| CD20-positive area ratio | 0.02 | 0.769 |

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. LN, lymph node.

The number of CD56-positive cells in the largest diameter LNs positively correlated with the number of retrieved LNs, the long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, and the CD3-positive area and CD20-positive area in the largest diameter LNs, but did not correlate with the CD3-positive area ratio or CD20-positive area ratio.

Discussion

In patients with stage II colon cancer, stage migration was previously thought to be one of the major reasons why patients with retrieval of more LNs have better outcomes [3, 24, 25]. However, failure to detect lymph-node metastasis does not happen frequently [26], and the number of negative LNs is related to outcomes in patients with stage III disease [6]. Therefore, recent studies have speculated the involvement of the host's immune response against cancer [27, 28].

In the present study, we hypothesized that the immune response of regional LNs against cancer is related to lymph-node size and the number of retrieved LNs in patients with stage II colon cancer. This hypothesis is supported by the findings that a high number of CD56-positive cells in the largest diameter LNs was associated with more retrieved LNs, a larger long-axis diameter of the largest diameter LNs, and significantly better outcomes.

High levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have been reported to be associated with better outcomes [29] and the retrieval of higher numbers of LNs in colorectal cancer [30]. To our knowledge, however, no previous study has reported on the relations of immune response in LNs to the number of retrieved LNs and outcomes.

In the tumor-node-metastasis staging system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC), colorectal cancer is classified according to histologic characteristics to predict outcomes and to determine the treatment of choice in the individual patient. Recently, classifications based on the host immune response to cancer have been reported [31, 32]. At present, immune scores are being calculated by counting the numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD3- and CD8-positive T-lymphocytes in an ongoing international multicenter, collaborative, prospective study [33]. However, NK cells are not being evaluated [33]. Previous studies have reported that tumor-infiltrating NK cells are found only in 31% of patients with colorectal cancer [34] and that NK cells alone are not a prognostic factor [35]. In our study, only 0.6% of the patients had no NK cells in the largest diameter LNs, and NK cells alone were an independent prognostic factor. This finding suggests that NK cells should be evaluated in LNs rather than in the primary tumors in patients with colorectal cancer.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that at least 12 LNs should be retrieved to prevent stage migration [27]. In patients with stage II colon cancer, retrieval of less than 12 LNs is considered a risk factor for recurrence for which postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered [27]. However, the number of retrieved LNs may be influenced by other factors, such as surgical procedures [36, 37], the extent of resection margins [38], and pathological methods [39]. It is easy to select and evaluate one of the largest LNs, which is less likely to be affected by the external factors mentioned above. Therefore, the number of NK cells in the largest diameter LN may be as useful as the number of retrieved LNs as a predictor of recurrence.

CD3 and CD20-positive area ratios and the number of CD56-positive cells are all significantly related to outcomes in univariate analysis; however, only the number of CD56-positive cells was an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis. We could not explain the reasons for these findings in the present study.

Because the proportion of NK cells in the largest diameter LNs is small, NK cells do not directly influence the size of LNs. Apart from tumor metastasis, an increase in LN size can be caused by hyperplasia of cellular components in LNs [40]. Activated NK cells secrete interferon-γ and activate T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells [41, 42]. In our study, high numbers of NK cells in the largest diameter LNs were unrelated to the proportions of T cells and B cells but were associated with larger areas of T cells and B cells and a larger long-axis diameter of LNs. Therefore, lymph-node size was most likely increased by hyperplasia of other immune cells activated by NK cells. Further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Because our study focused on patients who had stage II colon cancer with no lymph-node metastasis, further studies in patients with stage III disease who have lymph-node metastasis are needed. Because our study was performed in a single center, our results should be reevaluated in a multicenter study.

Conclusions

The area ratios of T cells and B cells and the number of NK cells in the largest diameter LNs were related to the sizes of the largest diameter LNs in patients with Stage II colon cancer. The number of NK cells correlated with the number of retrieved LNs and was an independent prognostic factor. The number of NK cells in the largest diameter LNs may reflect the tumor immunity of the host immune response and can thus most likely be used as a predictor of recurrence.

Disclosure Statement

K.O., S.S., L.F.C., T.O., H.M., G.S., A.T., and T.S. have reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Goldstein NS. Lymph node recoveries from 2427 pT3 colorectal resection specimens spanning 45 years: recommendations for a minimum number of recovered lymph nodes based on predictive probabilities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:179–189. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cserni G, Vinh-Hung V, Burzykowski T. Is there a minimum number of lymph nodes that should be histologically assessed for a reliable nodal staging of T3N0M0 colorectal carcinomas? J Surg Oncol. 2002;81:63–69. doi: 10.1002/jso.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, Mayer RJ, Macdonald JS, Catalano PJ, Haller DG. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2912–2919. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, Bland KI. The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:65–71. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarli L, Bader G, Iusco D, Salvemini C, Mauro DD, Mazzeo A, Regina G, Roncoroni L. Number of lymph nodes examined and prognosis of TNM stage II colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson PM, Porter GA, Ricciardi R, Baxter NN. Increasing negative lymph node count is independently associated with improved long-term survival in stage IIIB and IIIC colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3570–3575. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SL, Bilchik AJ. More extensive nodal dissection improves survival for stages I to III of colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 2006;244:602–610. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237655.11717.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Moyer VA. Lymph node evaluation and survival after curative resection of colon cancer: systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:433–441. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK, The Will Rogers phenomenon Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604–1608. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph NE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, Wang H, Mayer RJ, MacDonald JS, Catalano PJ, Haller DG. Accuracy of determining nodal negativity in colorectal cancer on the basis of the number of nodes retrieved on resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:213–218. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pheby DF, Levine DF, Pitcher RW, Shepherd NA. Lymph node harvests directly influence the staging of colorectal cancer: evidence from a regional audit. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:43–47. doi: 10.1136/jcp.57.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller EA, Woosley J, Martin CF, Sandler RS. Hospital-to-hospital variation in lymph node detection after colorectal resection. Cancer. 2004;101:1065–1071. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caplin S, Cerottini JP, Bosman FT, Constanda MT, Givel JC. For patients with Dukes' B (TNM Stage II) colorectal carcinoma, examination of six or fewer lymph nodes is related to poor prognosis. Cancer. 1998;83:666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markl B. Stage migration vs. immunology: the lymph node count story in colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12218–12233. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markl B, Schaller T, Kokot Y, Endhardt K, Kretsinger H, Hirschbuhl K, Aumann G, Schenkirsch G. Lymph node size as a simple prognostic factor in node negative colon cancer and an alternative thesis to stage migration. Am J Surg. 2015;212:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markl B, Rossle J, Arnholdt HM, Schaller T, Krammer I, Cacchi C, Jahnig H, Schenkirsch G, Spatz H, Anthuber M. The clinical significance of lymph node size in colon cancer. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1413–1422. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sloothaak DA, Grewal S, Doornewaard H, van Duijvendijk P, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA, van der Zaag ES, Buskens CJ. Lymph node size as a predictor of lymphatic staging in colonic cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101:701–706. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okada K, Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Tanaka A, Saito G, Masuda S, Haruki Y. The size of retrieved lymph nodes correlates with the number of retrieved lymph nodes and is an independent prognostic factor in patients with stage II colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1685–1693. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy J, Pocard M, Jass JR, O'Sullivan GC, Lee G, Talbot IC. Number and size of lymph nodes recovered from dukes B rectal cancers: correlation with prognosis and histologic antitumor immune response. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1526–1534. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong SL, Ji H, Hollenbeck BK, Morris AM, Baser O, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital lymph node examination rates and survival after resection for colon cancer. JAMA. 2007;298:2149–2154. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillman RO, Aaron K, Heinemann FS, McClure SE. Identification of 12 or more lymph nodes in resected colon cancer specimens as an indicator of quality performance. Cancer. 2009;115:1840–1848. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vather R, Sammour T, Kahokehr A, Connolly AB, Hill AG. Lymph node evaluation and long-term survival in Stage II and Stage III colon cancer: a national study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:585–593. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum . 2nd English edition. Tokyo: Kanehara and Co, Ltd; 2009. Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma; pp. pp 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bilimoria KY, Palis B, Stewart AK, Bentrem DJ, Freel AC, Sigurdson ER, Talamonti MS, Ko CY. Impact of tumor location on nodal evaluation for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:154–161. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lykke J, Roikjaer O, Jess P. The relation between lymph node status and survival in Stage I-III colon cancer: results from a prospective nationwide cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:559–565. doi: 10.1111/codi.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Schmitt SL, Nogueras JJ, Lucas FV. Effect of xylene clearance of mesenteric fat on harvest of lymph nodes after colonic resection. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:693–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Colonl Cancer. 2018;V.1 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/colon.pdf (accessed March 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong SL. Lymph node evaluation in colon cancer: assessing the link between quality indicators and quality. JAMA. 2011;306:1139–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George S, Primrose J, Talbot R, Smith J, Mullee M, Bailey D, du Boulay C, Jordan H, Wessex Colorectal Cancer Audit Working G Will Rogers revisited: prospective observational study of survival of 3592 patients with colorectal cancer according to number of nodes examined by pathologists. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:841–847. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YW, Jan KM, Jung DH, Cho MY, Kim NK. Histological inflammatory cell infiltration is associated with the number of lymph nodes retrieved in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5143–5150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Bindea G, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F, Galon J. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:610–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galon J, Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK, Berger A, Lagorce C, Lugli A, Zlobec I, Hartmann A, Bifulco C, Nagtegaal ID, Palmqvist R, Masucci GV, Botti G, Tatangelo F, Delrio P, Maio M, Laghi L, Grizzi F, Asslaber M, D'Arrigo C, Vidal-Vanaclocha F, Zavadova E, Chouchane L, Ohashi PS, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Wouters BG, Roehrl M, Nguyen L, Kawakami Y, Hazama S, Okuno K, Ogino S, Gibbs P, Waring P, Sato N, Torigoe T, Itoh K, Patel PS, Shukla SN, Wang Y, Kopetz S, Sinicrope FA, Scripcariu V, Ascierto PA, Marincola FM, Fox BA, Pages F. Towards the introduction of the “Immunoscore” in the classification of malignant tumours. J Pathol. 2014;232:199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sconocchia G, Eppenberger S, Spagnoli GC, Tornillo L, Droeser R, Caratelli S, Ferrelli F, Coppola A, Arriga R, Lauro D, Iezzi G, Terracciano L, Ferrone S. NK cells and T cells cooperate during the clinical course of colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e952197. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.952197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sconocchia G, Zlobec I, Lugli A, Calabrese D, Iezzi G, Karamitopoulou E, Patsouris ES, Peros G, Horcic M, Tornillo L, Zuber M, Droeser R, Muraro MG, Mengus C, Oertli D, Ferrone S, Terracciano L, Spagnoli GC. Tumor infiltration by FcgammaRIII (CD16)+ myeloid cells is associated with improved survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2663–2672. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, Wilhelmsen M, Kirkegaard-Klitbo A, Tenma JR, Bols B, Ingeholm P, Rasmussen LA, Jepsen LV, Iversen ER, Kristensen B, Gogenur I, Danish Colorectal Cancer G Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada K, Sadahiro S, Ogimi T, Miyakita H, Saito G, Tanaka A, Suzuki T. Tattooing improves the detection of small lymph nodes and increases the number of retrieved lymph nodes in patients with rectal cancer who receive preoperative chemoradiotherapy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Surg. 2018;215:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West NP, Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Perrakis A, Weber K, Hohenberger W, Sugihara K, Quirke P. Understanding optimal colonic cancer surgery: comparison of Japanese D3 resection and European complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1763–1769. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott KW, Grace RH. Detection of lymph node metastases in colorectal carcinoma before and after fat clearance. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1165–1167. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss LM, O'Malley D. Benign lymphadenopathies. Mod Pathol Jan. 2013;26:88–96. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferlazzo G, Pack M, Thomas D, Paludan C, Schmid D, Strowig T, Bougras G, Muller WA, Moretta L, Munz C. Distinct roles of IL-12 and IL-15 in human natural killer cell activation by dendritic cells from secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16606–16611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407522101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]